Vasopressin Improves Cerebral Perfusion Pressure but Not Cerebral Blood Flow or Tissue Oxygenation in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Norepinephrine-Refractory Hypotension: A Preliminary Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics/IRB Statement

2.2. Study Design

2.2.1. Patient Selection and ICU Therapy

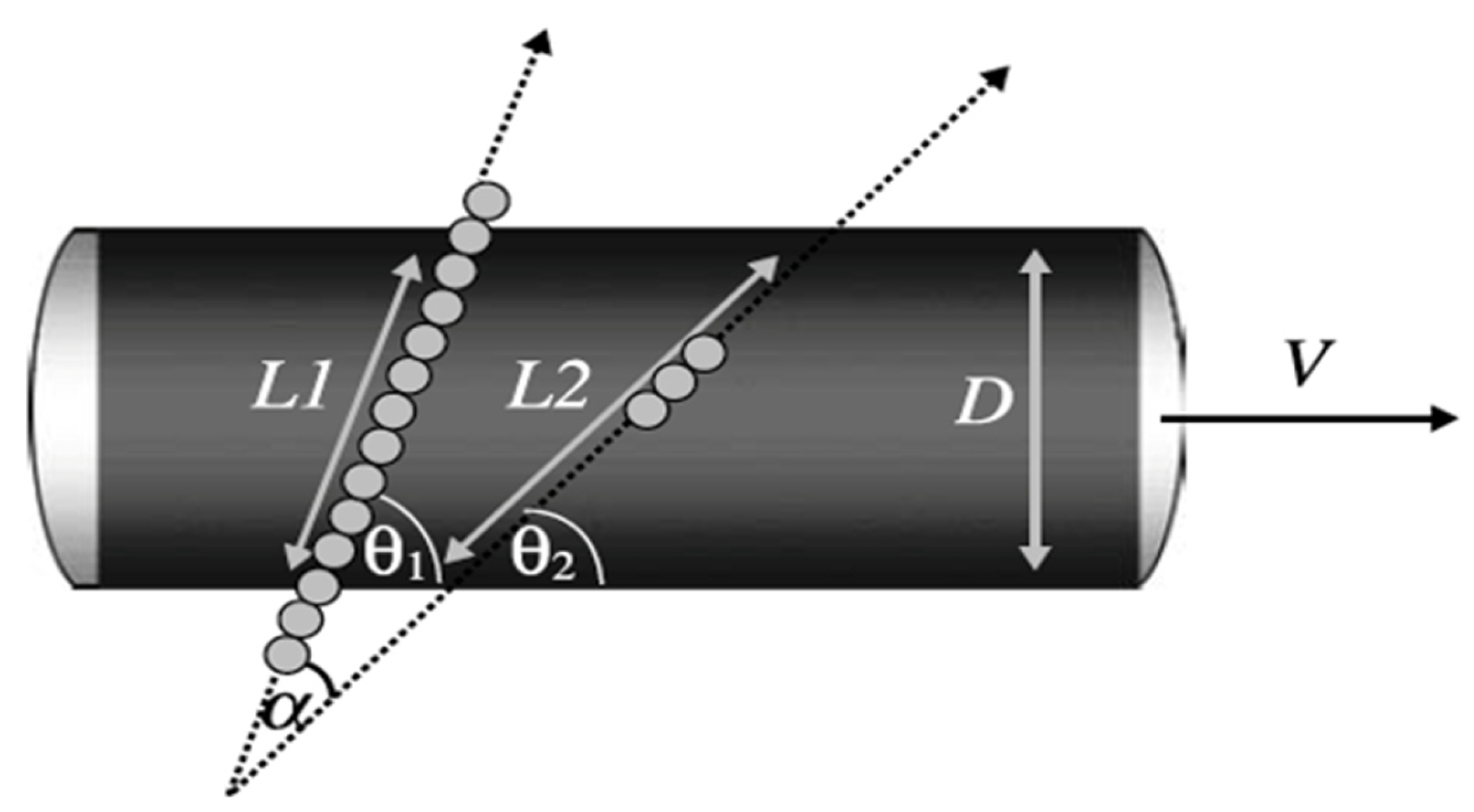

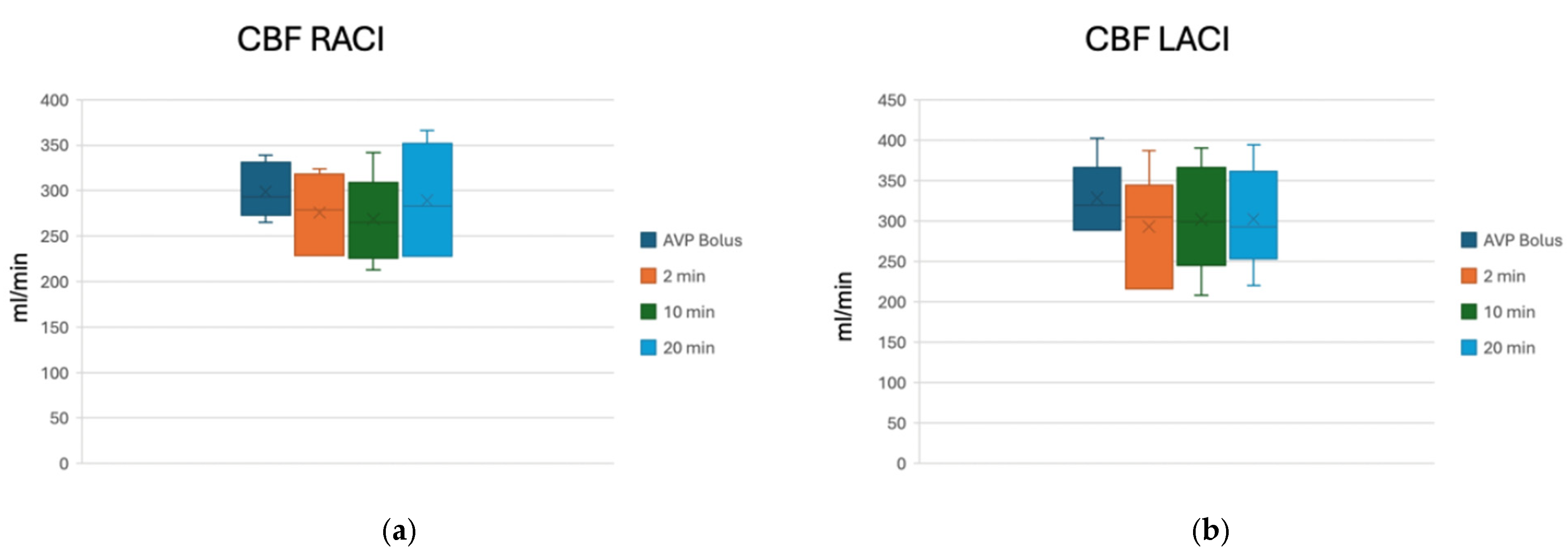

2.2.2. Therapeutic Intervention and CBF Monitoring

2.2.3. Flow Chart of Decision to Administer Vasopressin (Scheme 1)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Case Vignette

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Shortcomings

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aSAH | aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| CPP | cerebral perfusion pressure |

| CPPopt | optimal cerebral perfusion pressure |

| CBF | cerebral blood flow |

| MAP | mean arterial pressure |

| ICP | intracranial pressure |

| PbtO2 | brain tissue oxygenation |

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| AVP | arginin-vasopressin or terlipressin |

| AVPR | arginin-vasopressin receptor |

| PRx | pressure reactivity index |

| ICU | intensive care unit |

| CV | cerebral vasospasm |

| TCD | transcranial Doppler |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Score |

| GOS | Glasgow Outcome Score |

| IU | international units |

| ICA | internal carotid artery |

| RMCA | right middle cerebral artery |

| LMCA | left middle cerebral artery |

| ACoA | anterior communicating artery |

| TP | time point |

| EBI | early brain injury |

| DCI | delayed cerebral ischemia |

| NMI | neurogenic myocardial injury |

| ACTH | adrenocorticotropic hormone |

References

- Helbok, R.; Schiefecker, A.J.; Beer, R.; Dietmann, A.; Antunes, A.P.; Sohm, F.; Fischer, M.; Hackl, W.O.; Rhomberg, P.; Lackner, P.; et al. Early brain injury after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A multimodal neuromonitoring study. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminan, N.; Macdonald, R.L. Management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2017, 140, 195–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gradys, A.; Szrama, J.; Molnar, Z.; Guzik, P.; Kusza, K. Cerebral Perfusion Pressure-Guided Therapy in Patients with Subarachnoid Haemorrhage-A Retrospective Analysis. Life 2023, 13, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, M.A.; Crandall, M.L.; Patel, M.B. Acute Management of Traumatic Brain Injury. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 97, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.T.; Wong, C.S.; Yeh, C.C.; Borel, C.O. Treatment of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage—A review. Acta Anaesthesiol. Taiwanica 2004, 42, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Keyrouz, S.G.; Diringer, M.N. Clinical review: Prevention and therapy of vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit. Care 2007, 11, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagno, M.; Geraldini, F.; Coppalini, G.; Robba, C.; Gouvea Bogossian, E.; Annoni, F.; Vitali, E.; Sterchele, E.D.; Balestra, C.; Taccone, F.S. The Impact of Inotropes and Vasopressors on Cerebral Oxygenation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Narrative Review. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.D.; Nyquist, P.A. The systemic implications of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007, 261, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; O’Kane, R. The Extracranial Consequences of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2018, 109, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, T.N.; Zimmerman, M.A.; Selzman, C.H. Vasopressin in the cardiac surgery intensive care unit. Am. J. Crit. Care 2002, 11, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farand, P.; Hamel, M.; Lauzier, F.; Plante, G.E.; Lesur, O. Review article: Organ perfusion/permeability-related effects of norepinephrine and vasopressin in sepsis. Can. J. Anaesth. 2006, 53, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.C.; Wu, C.T.; Lu, C.H.; Yang, C.P.; Wong, C.S. Early use of small-dose vasopressin for unstable hemodynamics in an acute brain injury patient refractory to catecholamine treatment: A case report. Anesth. Analg. 2003, 97, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkowska, A.B.; Biancardi, V.C.; Winklewski, P.J. Arginine Vasopressin, Synaptic Plasticity, and Brain Networks. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2022, 20, 2292–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, J.A. Bench-to-bedside review: Vasopressin in the management of septic shock. Crit. Care 2011, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoni, F.A.; Holmes, M.C.; Makara, G.B.; Karteszi, M.; Laszlo, F.A. Evidence that the effects of arginine-8-vasopressin (AVP) on pituitary corticotropin (ACTH) release are mediated by a novel type of receptor. Peptides 1984, 5, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaumer, M. Vasopressin receptors. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 11, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Vasopressor therapy in critically ill patients with shock. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 1503–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evora, P.R.; Pearson, P.J.; Schaff, H.V. Arginine vasopressin induces endothelium-dependent vasodilatation of the pulmonary artery. V1-receptor-mediated production of nitric oxide. Chest 1993, 103, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, T.; Ayajiki, K.; Fujioka, H.; Toda, N. Mechanisms underlying arginine vasopressin-induced relaxation in monkey isolated coronary arteries. J. Hypertens. 1999, 17, 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibonnier, M.; Conarty, D.M.; Preston, J.A.; Plesnicher, C.L.; Dweik, R.A.; Erzurum, S.C. Human vascular endothelial cells express oxytocin receptors. Endocrinology 1999, 140, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, M. Response to low-dose desmopressin by a subcutaneous route in children with type 1 von Willebrand disease. Hematology 2013, 18, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, A.J.; Patel, M.B.; Sanui, M.; Cohn, S.M.; Majetschak, M.; Proctor, K.G. Resuscitation with pressors after traumatic brain injury. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2005, 201, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieg, S.M.; Trabold, R.; Plesnila, N. Time-Dependent Effects of Arginine-Vasopressin V1 Receptor Inhibition on Secondary Brain Damage after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2017, 34, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Nakayama, S.; Amiry-Moghaddam, M.; Ottersen, O.P.; Bhardwaj, A. Arginine-vasopressin V1 but not V2 receptor antagonism modulates infarct volume, brain water content, and aquaporin-4 expression following experimental stroke. Neurocrit. Care 2010, 12, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameli, P.A.; Ameli, N.J.; Gubernick, D.M.; Ansari, S.; Mohan, S.; Satriotomo, I.; Buckley, A.K.; Maxwell, C.W., Jr.; Nayak, V.H.; Shushrutha Hedna, V. Role of vasopressin and its antagonism in stroke related edema. J. Neurosci. Res. 2014, 92, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudkiewicz, M.; Proctor, K.G. Tissue oxygenation during management of cerebral perfusion pressure with phenylephrine or vasopressin. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Haren, R.M.; Thorson, C.M.; Ogilvie, M.P.; Valle, E.J.; Guarch, G.A.; Jouria, J.A.; Busko, A.M.; Harris, L.T.; Bullock, M.R.; Jagid, J.R.; et al. Vasopressin for cerebral perfusion pressure management in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: Preliminary results of a randomized controlled trial. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013, 75, 1024–1030; discussion 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.A.; Song, J.A.; Shin, J.Y.; Yoon, J.J.; Yoo, K.Y.; Jeong, S. Background anaesthetic agents do not influence the impact of arginine vasopressin on haemodynamic states and cerebral oxygenation during shoulder surgery in the beach chair position: A prospective, single-blind study. BMC Anesth. 2017, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bele, S.; Proescholdt, M.A.; Hochreiter, A.; Schuierer, G.; Scheitzach, J.; Wendl, C.; Kieninger, M.; Schneiker, A.; Brundl, E.; Schodel, P.; et al. Continuous intra-arterial nimodipine infusion in patients with severe refractory cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A feasibility study and outcome results. Acta Neurochir. 2015, 157, 2041–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, N.; Totten, A.M.; O’Reilly, C.; Ullman, J.S.; Hawryluk, G.W.; Bell, M.J.; Bratton, S.L.; Chesnut, R.; Harris, O.A.; Kissoon, N.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soustiel, J.F.; Glenn, T.C.; Vespa, P.; Rinsky, B.; Hanuscin, C.; Martin, N.A. Assessment of cerebral blood flow by means of blood-flow-volume measurement in the internal carotid artery: Comparative study with a 133xenon clearance technique. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2003, 34, 1876–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schebesch, K.M.; Woertgen, C.; Schlaier, J.; Brawanski, A.; Rothoerl, R.D. Doppler ultrasound measurement of blood flow volume in the extracranial internal carotid artery for evaluation of brain perfusion after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol. Res. 2007, 29, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortt, J.; Opat, S.S.; Gorniak, M.B.; Aumann, H.A.; Collecutt, M.F.; Street, A.M. A retrospective study of the utility of desmopressin (1-deamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin) trials in the management of patients with von Willebrand disorder. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2010, 32 Pt 1, e181–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, P.C. Use of desmopressin (DDAVP) in controlling aspirin-induced coagulopathy after cardiac surgery. Heart Lung 1994, 23, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saeki, Y.; Nagatomi, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Hiratani, S.; Shiomi, S.; Arakawa, T.; Kamata, T.; Kobayashi, K. Effects of vasopressin on gastric mucosal blood flow in portal hypertension. Gastroenterol. JPN 1991, 26 (Suppl. S3), 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cossu, A.P.; Mura, P.; De Giudici, L.M.; Puddu, D.; Pasin, L.; Evangelista, M.; Xanthos, T.; Musu, M.; Finco, G. Vasopressin in hemorrhagic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized animal trials. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 421291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krismer, A.C.; Wenzel, V.; Stadlbauer, K.H.; Mayr, V.D.; Lienhart, H.G.; Arntz, H.R.; Lindner, K.H. Vasopressin during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A progress report. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32 (Suppl. S9), S432–S435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, D.W.; Levin, H.R.; Gallant, E.M.; Ashton, R.C., Jr.; Seo, S.; D’Alessandro, D.; Oz, M.C.; Oliver, J.A. Vasopressin deficiency contributes to the vasodilation of septic shock. Circulation 1997, 95, 1122–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauen, K.; Trabold, R.; Brem, C.; Terpolilli, N.A.; Plesnila, N. Arginine vasopressin V1a receptor-deficient mice have reduced brain edema and secondary brain damage following traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 1442–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockel, K.; Scholler, K.; Trabold, R.; Nussberger, J.; Plesnila, N. Vasopressin V(1a) receptors mediate posthemorrhagic systemic hypertension thereby determining rebleeding rate and outcome after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke J. Cereb. Circ. 2012, 43, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, S.A.; de Moya, M.A.; Zuccarelli, J.E.; Norenberg, M.D.; Proctor, K.G. Cerebrovascular resuscitation after polytrauma and fluid restriction. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2007, 204, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzi, A.; Otsuki, D.A.; Andrade, L.; Paiva, W.; Souza, F.L.; Aureliano, L.G.C.; Malbouisson, L.M.S. Can a Therapeutic Strategy for Hypotension Improve Cerebral Perfusion and Oxygenation in an Experimental Model of Hemorrhagic Shock and Severe Traumatic Brain Injury? Neurocrit. Care 2023, 39, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, F. Neurotrauma and Intracranial Pressure Management. Crit. Care Clin. 2023, 39, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tas, J.; Beqiri, E.; van Kaam, R.C.; Czosnyka, M.; Donnelly, J.; Haeren, R.H.; van der Horst, I.C.C.; Hutchinson, P.J.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Liberti, A.L.; et al. Targeting Autoregulation-Guided Cerebral Perfusion Pressure after Traumatic Brain Injury (COGiTATE): A Feasibility Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 2790–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelborghs, K.; Haseldonckx, M.; Van Reempts, J.; Van Rossem, K.; Wouters, L.; Borgers, M.; Verlooy, J. Impaired autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in an experimental model of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2000, 17, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glushakova, O.Y.; Johnson, D.; Hayes, R.L. Delayed increases in microvascular pathology after experimental traumatic brain injury are associated with prolonged inflammation, blood-brain barrier disruption, and progressive white matter damage. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depreitere, B.; Guiza, F.; Van den Berghe, G.; Schuhmann, M.U.; Maier, G.; Piper, I.; Meyfroidt, G. Pressure autoregulation monitoring and cerebral perfusion pressure target recommendation in patients with severe traumatic brain injury based on minute-by-minute monitoring data. J. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czosnyka, M.; Czosnyka, Z.; Smielewski, P. Pressure reactivity index: Journey through the past 20 years. Acta Neurochir. 2017, 159, 2063–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, D.O.; Shutter, L.A.; Moore, C.; Temkin, N.R.; Puccio, A.M.; Madden, C.J.; Andaluz, N.; Chesnut, R.M.; Bullock, M.R.; Grant, G.A.; et al. Brain Oxygen Optimization in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Phase-II: A Phase II Randomized Trial. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, J.F.; Launey, Y.; Chabanne, R.; Gay, S.; Francony, G.; Gergele, L.; Vega, E.; Montcriol, A.; Couret, D.; Cottenceau, V.; et al. Intracranial pressure monitoring with and without brain tissue oxygen pressure monitoring for severe traumatic brain injury in France (OXY-TC): An open-label, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, J.F.; Vilotitch, A.; Gauss, T.; Adolle, A.; Bosson, J.L.; Bouzat, P.; Collaborators, O.-T.T. Sex Differences in Neurological Outcome at 6 and 12 Months Following Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. An Observational Analysis of the OXY-TC Trial. J. Neurotrauma 2025, 42, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Wong, C.E.; Hsu, H.H.; Chi, K.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Huang, Y.T.; Huang, C.Y. Brain Tissue Oxygen Combined with Intracranial Pressure Monitoring in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: An Updated Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis Following the OXY-TC Trial. World Neurosurg. 2025, 197, 123926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, P. Intracranial pressure after the BEST TRIP trial: A call for more monitoring. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2014, 20, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandgaard, S.; Sigurdsson, S.T. Point:Counterpoint: Sympathetic activity does/does not influence cerebral blood flow. Counterpoint: Sympathetic nerve activity does not influence cerebral blood flow. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008, 105, 1366–1367; discussion 1367–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thome, C.; Schubert, G.A.; Schilling, L. Hypothermia as a neuroprotective strategy in subarachnoid hemorrhage: A pathophysiological review focusing on the acute phase. Neurol. Res. 2005, 27, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, C.; Lucke-Wold, B.; Patel, C.; Abou-Al-Shaar, H.; Moor, R.; Mehkri, Y.; Still, M.; Goldman, M.; Miller, P.; Robicsek, S. What are we measuring? A refined look at the process of disrupted autoregulation and the limitations of cerebral perfusion pressure in preventing secondary injury after traumatic brain injury. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2022, 221, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppadoro, A.; Citerio, G. Subarachnoid hemorrhage: An update for the intensivist. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011, 77, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Anthofer, J.; Bele, S.; Wendl, C.; Kieninger, M.; Zeman, F.; Bruendl, E.; Schmidt, N.O.; Schebesch, K.M. Continuous intra-arterial nimodipine infusion as rescue treatment of severe refractory cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2022, 96, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treggiari, M.M.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Busl, K.M.; Caylor, M.M.; Citerio, G.; Deem, S.; Diringer, M.; Fox, E.; Livesay, S.; Sheth, K.N.; et al. Guidelines for the Neurocritical Care Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit. Care 2023, 39, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, J.; Czosnyka, M.; van der Horst, I.C.C.; Park, S.; van Heugten, C.; Sekhon, M.; Robba, C.; Menon, D.K.; Zeiler, F.A.; Aries, M.J.H. Cerebral multimodality monitoring in adult neurocritical care patients with acute brain injury: A narrative review. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1071161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | Age | Diagnosis | WFNS | GCS | AL | Vasospasm | GOS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | f | 57 | aSAH | 2 | 13 | MCA | y | 1 |

| Patient 2 | m | 43 | aSAH | 4 | 8 | ACoA | n | 5 |

| Patient 3 | f | 48 | aSAH | 3 | 11 | MCA | y | 3 |

| Patient 4 | m | 61 | aSAH | 1 | 15 | ACoA | y | 1 |

| Patient 5 | m | 40 | TBI | na | 7 | na | na | 4 |

| Patient 6 | f | 42 | aSAH | 3 | 9 | MCA | y | 3 |

| Patient 7 | f | 58 | aSAH | 2 | 13 | ACoA | n | 3 |

| (a) | ||||||||

| APAII | APA II x | Temp. | Hb | PaO2 | PaO2x | PaCO2 | PaCO2x | |

| Patient 1 | 5 | 9 | 37.1 | 10.4 | 96 | 90 | 45 | 38 |

| Patient 2 | 6 | 11 | 36.9 | 9.2 | 102 | 78 | 35 | 39 |

| Patient 3 | 8 | 12 | 37.0 | 8.6 | 92 | 83 | 32 | 38 |

| Patient 4 | 5 | 12 | 37.4 | 9.8 | 105 | 86 | 41 | 42 |

| Patient 5 | 8 | 14 | 36.1 | 9.6 | 94 | 74 | 35 | 37 |

| Patient 6 | 6 | 14 | 36.8 | 9.8 | 98 | 90 | 39 | 35 |

| (b) | ||||||||

| Creatinine 1 mg/dL | Creatinine 2 mg/dL | Sodium mmol/L | Lactate 1 mg/dL | Lactate 2 Mg/dL | ||||

| Patient 1 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 138 | 9 | 14 | |||

| Patient 2 | 0.69 | 1.15 | 142 | 10 | 15 | |||

| Patient 3 | 1.01 | 1.2 | 135 | 12 | 18 | |||

| Patient 4 | 0.66 | 0.93 | 141 | 5 | 17 | |||

| Patient 5 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 136 | 7 | 18 | |||

| Patient 6 | 1.23 | 1.43 | 142 | 10 | 16 | |||

| MAP Median | Range | CPP Median | Range | ICP Median | Range | PbtO2 Median | Range | LACI Median | RACI Median | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP1 | 58 | 52/61 | 40 | 37/44 | 18.5 | 12/22 | 15.5 | 12/22 | 319 | 293 |

| TP2 | 93 * | 87/108 | 77 * | 71/94 | 15 * | 10/17 | 16.5 * | 15/22 | 305 | 279 |

| TP3 | 96 * | 90/106 | 81 * | 76/91 | 15 * | 14/15 | 16.5 * | 14/24 | 299 | 264 |

| TP4 | 91 * | 86/96 | 75.5 * | 71/82 | 14.5 * | 12/16 | 17 * | 14/22 | 293 | 283 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bele, S.; Bruendl, E.; Schmidt, N.O.; Proescholdt, M.; Kieninger, M. Vasopressin Improves Cerebral Perfusion Pressure but Not Cerebral Blood Flow or Tissue Oxygenation in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Norepinephrine-Refractory Hypotension: A Preliminary Evaluation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238517

Bele S, Bruendl E, Schmidt NO, Proescholdt M, Kieninger M. Vasopressin Improves Cerebral Perfusion Pressure but Not Cerebral Blood Flow or Tissue Oxygenation in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Norepinephrine-Refractory Hypotension: A Preliminary Evaluation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238517

Chicago/Turabian StyleBele, Sylvia, Elisabeth Bruendl, Nils Ole Schmidt, Martin Proescholdt, and Martin Kieninger. 2025. "Vasopressin Improves Cerebral Perfusion Pressure but Not Cerebral Blood Flow or Tissue Oxygenation in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Norepinephrine-Refractory Hypotension: A Preliminary Evaluation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238517

APA StyleBele, S., Bruendl, E., Schmidt, N. O., Proescholdt, M., & Kieninger, M. (2025). Vasopressin Improves Cerebral Perfusion Pressure but Not Cerebral Blood Flow or Tissue Oxygenation in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Norepinephrine-Refractory Hypotension: A Preliminary Evaluation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8517. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238517