A Comprehensive Review of Current and Emerging Treatments for Narcolepsy Type 1

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Current Treatment

2.1. Pharmacological Treatment

2.1.1. EDS Pharmacological Treatment

Modafinil

Pitolisant

Solriamfetol

Sodium Oxybate (SXB) and Its Derivatives

Other Wake-Promoting Agents

2.1.2. Cataplexy Pharmacological Treatment

First-Line Treatment

Second-Line Treatment (Antidepressants)

Exacerbation of Cataplexy Following Withdrawal of Antidepressants

2.2. Nonpharmacological Treatment

2.3. Special Populations

3. Emerging Treatments

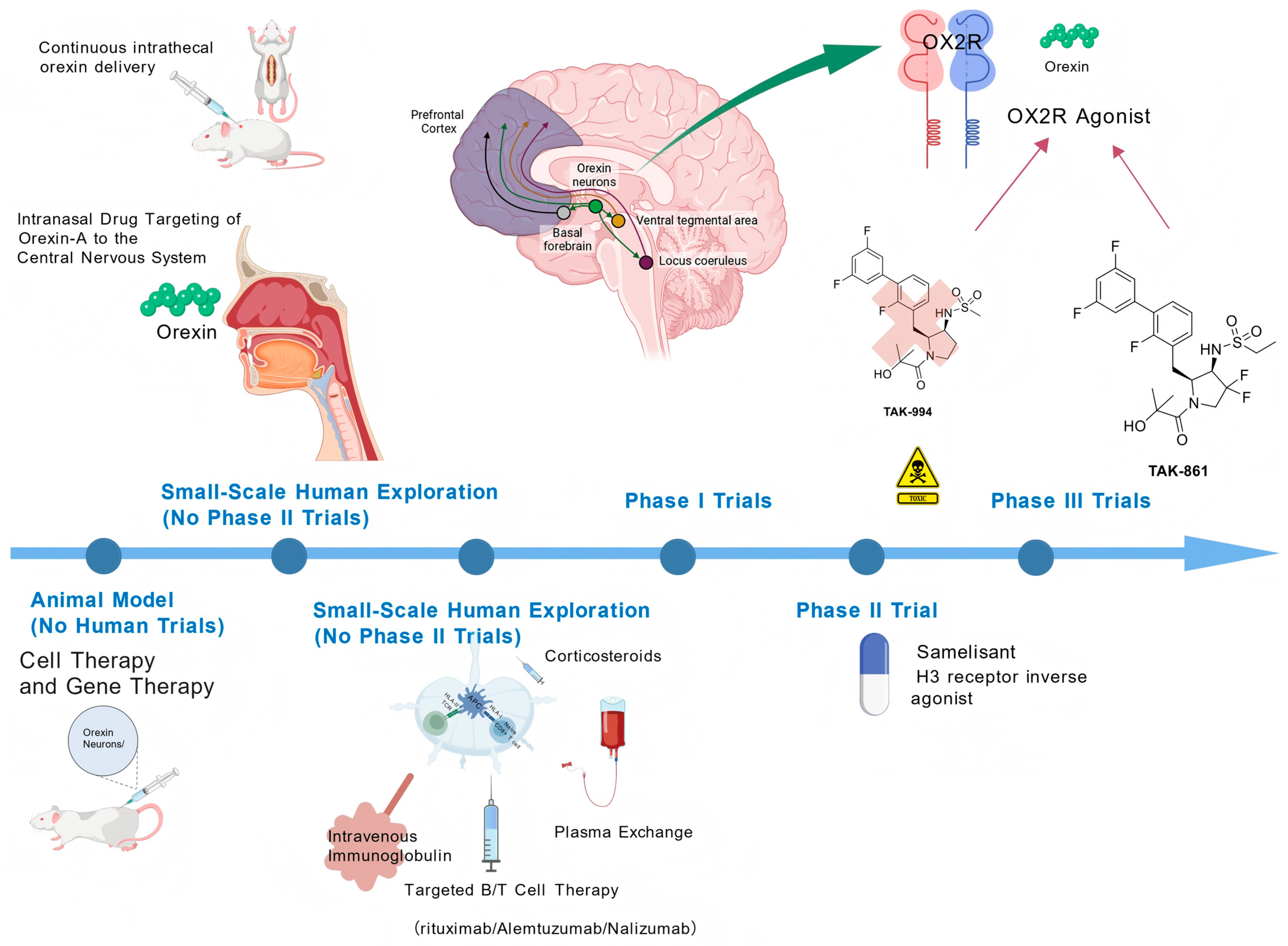

3.1. Orexin System Targeted Therapy

3.1.1. Orexin Receptor Agonists

Preclinical Studies of OX2R Selective Agonists

Clinical Trials of OX2R Selective Agonists

3.1.2. Orexin Replacement Therapy

Efficacy and Dosage Exploration in Animal Studies

The Findings and Limitations of Human Clinical Trials

3.2. Immunotherapy

- Environmental Triggers: 1. Streptococcal Infection: Individuals who developed streptococcal pharyngitis before age 21 exhibit increased NT1 risk, with higher serum streptococcal antibody levels within 3 years of onset compared to controls [110]; 2. H1N1 infection/vaccination: NT1 incidence tripled within 6 months following China’s H1N1 pandemic [111]; increased incidence among Pandemrix vaccine recipients [112,113], suggesting molecular mimicry between the H1N1 HA protein and hypocretin [114].

- Immune cell involvement: 1. CD4+ T cells: Patients harbor hypocretin-specific CD4+ T cells capable of cross-recognizing H1N1 HA protein [114]; 2. CD8+ T cells: Increased autoreactive CD8+ T cells in patient blood [115], and in animal models, CD8+ T cells can directly destroy orexin neurons [116]; CD8+ T cell clones in CSF correlate with progression from NT2 to NT1 [117].

- Evidence of autoantibodies: 1. TRIB2 antibody: Positive in 14% of patients, but also positive in 5% of controls. Acts as an intracellular antigen with no direct pathogenic role [118]; 2. HCRTR2 antibody: Positive in 85% of post-vaccination NT1 cases (vs. 35% controls), absent in idiopathic NT1, lacking core pathogenic significance [119].

3.3. Cell Therapy and Gene Therapy

3.3.1. Cell Transplantation

3.3.2. Gene Transfer

3.4. Other New Drugs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sateia, M.J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: Highlights and modifications. Chest 2014, 146, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liblau, R.S.; Latorre, D.; Kornum, B.R.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Mignot, E.J. The immunopathogenesis of narcolepsy type 1. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scammell, T.E. Narcolepsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2654–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, C.E.; Cogswell, A.; Koralnik, I.J.; Scammell, T.E. The neurobiological basis of narcolepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, A.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Harris, S.; Gow, M. Narcolepsy: Beyond the Classic Pentad. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M.; Thorpy, M.J.; Carls, G.; Black, J.; Cisternas, M.; Pasta, D.J.; Bujanover, S.; Hyman, D.; Villa, K.F. The Nexus Narcolepsy Registry: Methodology, study population characteristics, and patterns and predictors of narcolepsy diagnosis. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Thorpy, M. Clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of narcolepsy. Clin. Chest Med. 2010, 31, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Adamantidis, A.; Burdakov, D.; Han, F.; Gay, S.; Kallweit, U.; Khatami, R.; Koning, F.; Kornum, B.R.; Lammers, G.J.; et al. Narcolepsy—Clinical spectrum, aetiopathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maski, K.; Trotti, L.M.; Kotagal, S.; Robert Auger, R.; Rowley, J.A.; Hashmi, S.D.; Watson, N.F. Treatment of central disorders of hypersomnolence: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 1881–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Kallweit, U.; Vignatelli, L.; Plazzi, G.; Lecendreux, M.; Baldin, E.; Dolenc-Groselj, L.; Jennum, P.; Khatami, R.; Manconi, M.; et al. European guideline and expert statements on the management of narcolepsy in adults and children. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, M.Y.; Karimvandi, M.N.; Nikbakhtzadeh, M.; Zahedi, E.; Bokov, D.O.; Kujawska, M.; Heidari, M.; Rahmani, M.R. Effects of Modafinil (Provigil) on Memory and Learning in Experimental and Clinical Studies: From Molecular Mechanisms to Behaviour Molecular Mechanisms and Behavioural Effects. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2023, 16, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicki, D.; Bala, M.M.; Niewada, M.; Wierzbicka, A. Modafinil for narcolepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2010, 16, Ra177–Ra186. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, P.M.; Schwartz, J.R.; Feldman, N.T.; Hughes, R.J. Effect of modafinil on fatigue, mood, and health-related quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. Psychopharmacology 2004, 171, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldofsky, H.; Broughton, R.J.; Hill, J.D. A randomized trial of the long-term, continued efficacy and safety of modafinil in narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2000, 1, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.C.; Huang, Y.S.; Trevor Lam, N.Y.; Mak, K.Y.; Tang, I.; Wang, C.H.; Lin, C. Effects of modafinil on nocturnal sleep patterns in patients with narcolepsy: A cohort study. Sleep Med. 2024, 119, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, C.; Pizza, F.; Cavalli, F.; Plazzi, G. A practical guide to the pharmacological and behavioral therapy of Narcolepsy. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, P.J.; Wolf, C.T. Psychosis in a 22-Year-Old Woman With Narcolepsy After Restarting Sodium Oxybate. Psychosomatics 2018, 59, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui-Furukori, N.; Kusunoki, M.; Kaneko, S. Hallucinations associated with modafinil treatment for narcolepsy. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 29, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, V.; Philippidou, M.; Walsh, S.; Creamer, D. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by modafinil. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 43, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesta, C.E.; Engeland, A.; Karlsson, P.; Kieler, H.; Reutfors, J.; Furu, K. Incidence of Malformations After Early Pregnancy Exposure to Modafinil in Sweden and Norway. JAMA 2020, 324, 895–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Braverman, D.L.; Frishman, I.; Bartov, N. Pregnancy and Fetal Outcomes Following Exposure to Modafinil and Armodafinil During Pregnancy. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, J. Pitolisant for treating patients with narcolepsy. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Arnulf, I.; Szakacs, Z.; Leu-Semenescu, S.; Lecomte, I.; Scart-Gres, C.; Lecomte, J.M.; Schwartz, J.C. Long-term use of pitolisant to treat patients with narcolepsy: Harmony III Study. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Río-Villegas, R.; Martínez-Orozco, F.J.; Romero-Santo Tomás, O.; Yébenes-Cortés, M.; Gómez-Barrera, M.; Gaig-Ventura, C. Real-life WAKE study in narcolepsy patients with cataplexy treated with pitolisant and unresponsive to previous treatments. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 75, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plazzi, G.; Mayer, G.; Bodenschatz, R.; Bonanni, E.; Cicolin, A.; Della Marca, G.; Dolso, P.; Strambi, L.F.; Ferri, R.; Geisler, P.; et al. Interim analysis of a post-authorization safety study of pitolisant in treating narcolepsy: A real-world European study. Sleep Med. 2025, 129, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Lecendreux, M.; Lammers, G.J.; Franco, P.; Poluektov, M.; Caussé, C.; Lecomte, I.; Lecomte, J.M.; Lehert, P.; Schwartz, J.C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of pitolisant in children aged 6 years or older with narcolepsy with or without cataplexy: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triller, A.; Pizza, F.; Lecendreux, M.; Lieberich, L.; Rezaei, R.; Pech de Laclause, A.; Vandi, S.; Plazzi, G.; Kallweit, U. Real-world treatment of pediatric narcolepsy with pitolisant: A retrospective, multicenter study. Sleep Med. 2023, 103, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Y.; Lang, C.; Kallweit, U.; Apel, D.; Fleischer, V.; Ellwardt, E.; Groppa, S. Pitolisant-supported bridging during drug holidays to deal with tolerance to modafinil in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2023, 112, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, R.; Singh, R.; Thakur, R.K.; C, B.K.; Jha, D.; Ray, B.K. Efficacy and safety of solriamfetol for excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, M.C.; Carlson, S.; Pysick, H.; Berry, V.; Tondryk, A.; Swartz, H.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.M.; Viswanath, O.; Urits, I.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Solriamfetol to Treat Excessive Daytime Sleepiness. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2024, 54, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Shapiro, C.; Mayer, G.; Lammers, G.J.; Emsellem, H.; Plazzi, G.; Chen, D.; Carter, L.P.; Lee, L.; Black, J.; et al. Solriamfetol for the Treatment of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Participants with Narcolepsy with and without Cataplexy: Subgroup Analysis of Efficacy and Safety Data by Cataplexy Status in a Randomized Controlled Trial. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpy, M.J.; Shapiro, C.; Mayer, G.; Corser, B.C.; Emsellem, H.; Plazzi, G.; Chen, D.; Carter, L.P.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; et al. A randomized study of solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in narcolepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.Y.; Kuo, C.Y.; Lin, M.H.; Chang, Y.J.; Hung, C.C. Pharmacological Interventions for Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Adults with Narcolepsy: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, S.; Ye, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Hou, Y. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Multiple Wake-Promoting Agents for the Treatment of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Narcolepsy: A Network Meta-Analysis. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2023, 15, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Shapiro, C.; Pepin, J.L.; Hedner, J.; Ahmed, M.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Strollo, P.J.; Mayer, G.; Sarmiento, K.; Baladi, M.; et al. Long-term study of the safety and maintenance of efficacy of solriamfetol (JZP-110) in the treatment of excessive sleepiness in participants with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2020, 43, zsz220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystal, A.D.; Benca, R.M.; Rosenberg, R.; Schweitzer, P.K.; Malhotra, A.; Babson, K.; Lee, L.; Bujanover, S.; Strohl, K.P. Solriamfetol treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in participants with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea with a history of depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 155, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, A.; Strollo, P.J., Jr.; Pepin, J.L.; Schweitzer, P.; Lammers, G.J.; Hedner, J.; Redline, S.; Chen, D.; Chandler, P.; Bujanover, S.; et al. Effects of solriamfetol treatment on body weight in participants with obstructive sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2022, 100, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.M.; Keating, G.M. Sodium oxybate: A review of its use in the management of narcolepsy. CNS Drugs 2007, 21, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazzi, G.; Ruoff, C.; Lecendreux, M.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Rosen, C.L.; Black, J.; Parvataneni, R.; Guinta, D.; Wang, Y.G.; Mignot, E. Treatment of paediatric narcolepsy with sodium oxybate: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised-withdrawal multicentre study and open-label investigation. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xyrem® International Study Group. Further evidence supporting the use of sodium oxybate for the treatment of cataplexy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 228 patients. Sleep Med. 2005, 6, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Houghton, W.C. Sodium oxybate improves excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy. Sleep 2006, 29, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Pardi, D.; Hornfeldt, C.S.; Inhaber, N. The nightly administration of sodium oxybate results in significant reduction in the nocturnal sleep disruption of patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakatos, P.; Lykouras, D.; D’Ancona, G.; Higgins, S.; Gildeh, N.; Macavei, R.; Rosenzweig, I.; Steier, J.; Williams, A.J.; Muza, R.; et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term use of sodium oxybate for narcolepsy with cataplexy in routine clinical practice. Sleep Med. 2017, 35, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaikh, M.K.; Tricco, A.C.; Tashkandi, M.; Mamdani, M.; Straus, S.E.; BaHammam, A.S. Sodium oxybate for narcolepsy with cataplexy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamelak, M.; Swick, T.; Emsellem, H.; Montplaisir, J.; Lai, C.; Black, J. A 12-week open-label, multicenter study evaluating the safety and patient-reported efficacy of sodium oxybate in patients with narcolepsy and cataplexy. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, J.; Gross, W.L. Psychosis in the context of sodium oxybate therapy. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2011, 7, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkanen, T.; Niemelä, V.; Landtblom, A.M.; Partinen, M. Psychosis in patients with narcolepsy as an adverse effect of sodium oxybate. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecendreux, M.; Plazzi, G.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Rosen, C.L.; Ruoff, C.; Black, J.; Parvataneni, R.; Guinta, D.; Wang, Y.G.; Mignot, E. Long-term safety and maintenance of efficacy of sodium oxybate in the treatment of narcolepsy with cataplexy in pediatric patients. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 2217–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkelshoek, M.S.; Smolders, I.M.; Donjacour, C.E.; van der Meijden, W.P.; van Zwet, E.W.; Fronczek, R.; Lammers, G.J. Decreased body mass index during treatment with sodium oxybate in narcolepsy type 1. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Bogan, R.K.; Šonka, K.; Partinen, M.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Thorpy, M.J. Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium, and Sodium Oxybates Oral Solution: A Lower-Sodium Alternative for Cataplexy or Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Associated with Narcolepsy. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2022, 14, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogan, R.K.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Skowronski, R.; Chen, A.; Thorpy, M.J. Long-Term Safety and Tolerability During a Clinical Trial and Open-Label Extension of Low-Sodium Oxybate in Participants with Narcolepsy with Cataplexy. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, L.D.; Morse, A.M.; Strunc, M.J.; Lee-Iannotti, J.K.; Bogan, R.K. Long-Term Treatment of Narcolepsy and Idiopathic Hypersomnia with Low-Sodium Oxybate. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2023, 15, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Stern, T.; Harsh, J.; Hudson, J.D.; Ajayi, A.O.; Corser, B.C.; Mignot, E.; Santamaria, A.; Morse, A.M.; Abaluck, B.; et al. RESTORE: Once-nightly oxybate dosing preference and nocturnal experience with twice-nightly oxybates. Sleep Med. X 2024, 8, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahn, L.; Roy, A.; Winkelman, J.W.; Morse, A.M.; Gudeman, J. Assessing Early Efficacy After Initiation of Once-Nightly Sodium Oxybate (ON-SXB; FT218) in Participants with Narcolepsy Type 1 or 2: A Post Hoc Analysis from the Phase 3 REST-ON Trial. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsh, J.R.; Hayduk, R.; Rosenberg, R.; Wesnes, K.A.; Walsh, J.K.; Arora, S.; Niebler, G.E.; Roth, T. The efficacy and safety of armodafinil as treatment for adults with excessive sleepiness associated with narcolepsy. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2006, 22, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.E.; Hull, S.G.; Tiller, J.; Yang, R.; Harsh, J.R. The long-term tolerability and efficacy of armodafinil in patients with excessive sleepiness associated with treated obstructive sleep apnea, shift work disorder, or narcolepsy: An open-label extension study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2010, 6, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitler, M.M.; Shafor, R.; Hajdukovich, R.; Timms, R.M.; Browman, C.P. Treatment of narcolepsy: Objective studies on methylphenidate, pemoline, and protriptyline. Sleep 1986, 9, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, B.E.; McCartan, D.; White, J.; King, D.J. Methylphenidate: A review of its neuropharmacological, neuropsychological and adverse clinical effects. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 19, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, W.C.; Scammell, T.E.; Thorpy, M. Pharmacotherapy for cataplexy. Sleep Med. Rev. 2004, 8, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S.Xyrem® Multicenter Study Group. Sodium oxybate demonstrates long-term efficacy for the treatment of cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2004, 5, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakacs, Z.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Mikhaylov, V.; Poverennova, I.; Krylov, S.; Jankovic, S.; Sonka, K.; Lehert, P.; Lecomte, I.; Lecomte, J.M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of pitolisant on cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillen, S.; Pizza, F.; Dhondt, K.; Scammell, T.E.; Overeem, S. Cataplexy and Its Mimics: Clinical Recognition and Management. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2017, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Greenberg, H. Status cataplecticus precipitated by abrupt withdrawal of venlafaxine. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, M.; Parkes, J.D. Fluvoxamine and clomipramine in the treatment of cataplexy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1980, 43, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, W.R. Treatment of Cataplexy with Clomipramine. Arch. Neurol. 1975, 32, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, C.; Raynal, D.; Takahashi, S.; Carskadon, M.; Dement, W. Evaluation of short-term and long-term treatment of the narcolepsy syndrome with clomipramine hydrochloride. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1976, 54, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenthaler, T.I.; Kapur, V.K.; Brown, T.; Swick, T.J.; Alessi, C.; Aurora, R.N.; Boehlecke, B.; Chesson, A.L., Jr.; Friedman, L.; Maganti, R.; et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep 2007, 30, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristanovic, R.K.; Liang, H.; Hornfeldt, C.S.; Lai, C. Exacerbation of cataplexy following gradual withdrawal of antidepressants: Manifestation of probable protracted rebound cataplexy. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscarini, F.; Bassi, C.; Menchetti, M.; Zenesini, C.; Baldini, V.; Franceschini, C.; Varallo, G.; Antelmi, E.; Vignatelli, L.; Pizza, F.; et al. Co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and hopelessness in patients with narcolepsy type 1. Sleep Med. 2024, 124, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, L.E.; Morse, A.M.; Krahn, L.; Lavender, M.; Horsnell, M.; Cronin, D.; Schneider, B.; Gudeman, J. A Survey of People Living with Narcolepsy in the USA: Path to Diagnosis, Quality of Life, and Treatment Landscape from the Patient’s Perspective. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudka, S.; Haynes, E.; Scotney, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Frenkel, S.; Sivam, S.; Swieca, J.; Chamula, K.; Cunnington, D.; Saini, B. Narcolepsy: Comorbidities, complexities and future directions. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 65, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Agudelo, H.A.; Jiménez Correa, U.; Carlos Sierra, J.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Schenck, C.H. Cognitive behavioral treatment for narcolepsy: Can it complement pharmacotherapy? Sleep Sci. 2014, 7, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, J.C.; Dawson, S.C.; Mundt, J.M.; Moore, C. Developing a cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia using telehealth: A feasibility study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 2047–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehrs, T.; Zorick, F.; Wittig, R.; Paxton, C.; Sicklesteel, J.; Roth, T. Alerting effects of naps in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep 1986, 9, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullington, J.; Broughton, R. Scheduled naps in the management of daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy-cataplexy. Sleep 1993, 16, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Mayer, G.; Meier-Ewert, K. Differential effects of extended sleep in narcoleptic patients. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1994, 91, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardi, M.; Pizza, F.; Antelmi, E.; Pillastrini, P.; Natale, V.; Plazzi, G. Physical Activity and Sleep/Wake Behavior, Anthropometric, and Metabolic Profile in Pediatric Narcolepsy Type 1. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronczek, R.; Raymann, R.J.; Romeijn, N.; Overeem, S.; Fischer, M.; van Dijk, J.G.; Lammers, G.J.; Van Someren, E.J. Manipulation of core body and skin temperature improves vigilance and maintenance of wakefulness in narcolepsy. Sleep 2008, 31, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.M.; Yancy, W.S., Jr.; Carwile, S.T.; Miller, P.P.; Westman, E.C. Diet therapy for narcolepsy. Neurology 2004, 62, 2300–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, J.M.; Pruiksma, K.E.; Konkoly, K.R.; Casiello-Robbins, C.; Nadorff, M.R.; Franklin, R.C.; Karanth, S.; Byskosh, N.; Morris, D.J.; Torres-Platas, S.G.; et al. Treating narcolepsy-related nightmares with cognitive behavioural therapy and targeted lucidity reactivation: A pilot study. J. Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e14384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.G.; Jesteadt, L.; Crisp, C.; Simon, S.L. Treatment and care delivery in pediatric narcolepsy: A survey of parents, youth, and sleep physicians. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpy, M.; Zhao, C.G.; Dauvilliers, Y. Management of narcolepsy during pregnancy. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalská, P.; Kemlink, D.; Nevšímalová, S.; Maurovich Horvat, E.; Jarolímová, E.; Topinková, E.; Šonka, K. Narcolepsy with cataplexy in patients aged over 60 years: A case-control study. Sleep Med. 2016, 26, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.S.; Rye, D.B. Narcolepsy in the older adult: Epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging 2003, 20, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irukayama-Tomobe, Y.; Ogawa, Y.; Tominaga, H.; Ishikawa, Y.; Hosokawa, N.; Ambai, S.; Kawabe, Y.; Uchida, S.; Nakajima, R.; Saitoh, T.; et al. Nonpeptide orexin type-2 receptor agonist ameliorates narcolepsy-cataplexy symptoms in mouse models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5731–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Nagumo, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Irukayama-Tomobe, Y.; Namekawa, Y.; Nemoto, T.; Tanaka, H.; Takahashi, G.; Tokuda, A.; Saitoh, T.; et al. OX2R-selective orexin agonism is sufficient to ameliorate cataplexy and sleep/wake fragmentation without inducing drug-seeking behavior in mouse model of narcolepsy. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Hara, H.; Kawano, A.; Kimura, H. Danavorexton, a selective orexin 2 receptor agonist, provides a symptomatic improvement in a narcolepsy mouse model. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2022, 220, 173464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ranjan, A.; Tisdale, R.; Ma, S.C.; Park, S.; Haire, M.; Heu, J.; Morairty, S.R.; Wang, X.; Rosenbaum, D.M.; et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of the hypocretin/orexin receptor agonists TAK-925 and ARN-776 in narcoleptic orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Hara, H.; Kawano, A.; Tohyama, K.; Kajita, Y.; Miyanohana, Y.; Koike, T.; Kimura, H. TAK-994, a Novel Orally Available Brain-Penetrant Orexin 2 Receptor-Selective Agonist, Suppresses Fragmentation of Wakefulness and Cataplexy-Like Episodes in Mouse Models of Narcolepsy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2023, 385, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsukawa, K.; Terada, M.; Yamada, R.; Monjo, T.; Hiyoshi, T.; Nakakariya, M.; Kajita, Y.; Ando, T.; Koike, T.; Kimura, H. TAK-861, a potent, orally available orexin receptor 2-selective agonist, produces wakefulness in monkeys and improves narcolepsy-like phenotypes in mouse models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, D.; Siegrist, R.; Peters, J.U.; Kohl, C.; Mühlemann, A.; Schlienger, S.; Torrisi, C.; Lindenberg, E.; Kessler, M.; Roch, C. Discovery of a New Class of Orexin 2 Receptor Agonists as a Potential Treatment for Narcolepsy. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 10173–10189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.; Kimura, H.; Alexander, R.; Davies, C.H.; Faessel, H.; Hartman, D.S.; Ishikawa, T.; Ratti, E.; Shimizu, K.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Orexin 2 receptor-selective agonist danavorexton improves narcolepsy phenotype in a mouse model and in human patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207531119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Mignot, E.; Del Río Villegas, R.; Du, Y.; Hanson, E.; Inoue, Y.; Kadali, H.; Koundourakis, E.; Meyer, S.; Rogers, R.; et al. Oral Orexin Receptor 2 Agonist in Narcolepsy Type 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozawa, T.; Miyamoto, K.; Baker, K.S.; Faber, S.C.; Flores, R.; Uetrecht, J.; von Hehn, C.; Yukawa, T.; Tohyama, K.; Kadali, H.; et al. TAK-994 mechanistic investigation into drug-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 2025, 204, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Plazzi, G.; Mignot, E.; Lammers, G.J.; Del Río Villegas, R.; Khatami, R.; Taniguchi, M.; Abraham, A.; Hang, Y.; Kadali, H.; et al. Oveporexton, an Oral Orexin Receptor 2-Selective Agonist, in Narcolepsy Type 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignot, E.; Arnulf, I.; Plazzi, G. Efficacy and safety of Oveporexton (TAK-861), an oral orexin receptor 2 agonist for the treatment of narcolepsy type 1: Results from a phase 3 randomized study in Europe, Japan, and North America. In Proceedings of the World Sleep Congress 2025, Singapore, 8 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Antczak, J.; Buntinx, E.; del Rio Villegas, R.; Hong, S.C.; Sivam, S.; Zhan, S.; Koundourakis, E.; Neuwirth, R.; Olsson, T.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Oveporexton (TAK-861) for the treatment of narcolepsy type 1: Results from a phase 3 randomized study in Asia, Australia, and Europe. In Proceedings of the World Sleep Congress 2025, Singapore, 8 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Tian, R.; Wei, S.; Yang, H.; Zhu, C.; Li, Z. Activation of orexin receptor 2 plays anxiolytic effect in male mice. Brain Res. 2025, 1859, 149646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, J.; Wu, M.F.; Siegel, J.M. Systemic administration of hypocretin-1 reduces cataplexy and normalizes sleep and waking durations in narcoleptic dogs. Sleep Res. Online 2000, 3, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fujiki, N.; Yoshida, Y.; Ripley, B.; Mignot, E.; Nishino, S. Effects of IV and ICV hypocretin-1 (orexin A) in hypocretin receptor-2 gene mutated narcoleptic dogs and IV hypocretin-1 replacement therapy in a hypocretin-ligand-deficient narcoleptic dog. Sleep 2003, 26, 953–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deadwyler, S.A.; Porrino, L.; Siegel, J.M.; Hampson, R.E. Systemic and nasal delivery of orexin-A (Hypocretin-1) reduces the effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance in nonhuman primates. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 14239–14247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuria, S.V.; Hanson, L.R.; Frey, W.H., 2nd. Intranasal drug targeting of hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) to the central nervous system. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 2501–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, M.K.; Aritake, K.; Imanishi, A.; Kanbayashi, T.; Ichikawa, T.; Shimizu, T.; Urade, Y.; Yanagisawa, M. Continuous intrathecal orexin delivery inhibits cataplexy in a murine model of narcolepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6046–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, P.C.; Weinhold, S.L.; Huth, V.; Gottwald, B.; Ferstl, R.; Hinze-Selch, D. Olfactory dysfunction in patients with narcolepsy with cataplexy is restored by intranasal Orexin A (Hypocretin-1). Brain 2008, 131, 2734–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, P.C.; Hallschmid, M.; Seeck-Hirschner, M.; Weinhold, S.L.; Burkert, S.; Diessner, N.; Göder, R.; Aldenhoff, J.B.; Hinze-Selch, D. Effects of intranasal hypocretin-1 (orexin A) on sleep in narcolepsy with cataplexy. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinhold, S.L.; Seeck-Hirschner, M.; Nowak, A.; Hallschmid, M.; Göder, R.; Baier, P.C. The effect of intranasal orexin-A (hypocretin-1) on sleep, wakefulness and attention in narcolepsy with cataplexy. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 262, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Lin, L.; Schormair, B.; Pizza, F.; Plazzi, G.; Ollila, H.M.; Nevsimalova, S.; Jennum, P.; Knudsen, S.; Winkelmann, J.; et al. HLA DQB1*06:02 negative narcolepsy with hypocretin/orexin deficiency. Sleep 2014, 37, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallmayer, J.; Faraco, J.; Lin, L.; Hesselson, S.; Winkelmann, J.; Kawashima, M.; Mayer, G.; Plazzi, G.; Nevsimalova, S.; Bourgin, P.; et al. Narcolepsy is strongly associated with the T-cell receptor alpha locus. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornum, B.R.; Kawashima, M.; Faraco, J.; Lin, L.; Rico, T.J.; Hesselson, S.; Axtell, R.C.; Kuipers, H.; Weiner, K.; Hamacher, A.; et al. Common variants in P2RY11 are associated with narcolepsy. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aran, A.; Lin, L.; Nevsimalova, S.; Plazzi, G.; Hong, S.C.; Weiner, K.; Zeitzer, J.; Mignot, E. Elevated anti-streptococcal antibodies in patients with recent narcolepsy onset. Sleep 2009, 32, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Lin, L.; Warby, S.C.; Faraco, J.; Li, J.; Dong, S.X.; An, P.; Zhao, L.; Wang, L.H.; Li, Q.Y.; et al. Narcolepsy onset is seasonal and increased following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in China. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partinen, M.; Saarenpää-Heikkilä, O.; Ilveskoski, I.; Hublin, C.; Linna, M.; Olsén, P.; Nokelainen, P.; Alén, R.; Wallden, T.; Espo, M.; et al. Increased incidence and clinical picture of childhood narcolepsy following the 2009 H1N1 pandemic vaccination campaign in Finland. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakács, A.; Darin, N.; Hallböök, T. Increased childhood incidence of narcolepsy in western Sweden after H1N1 influenza vaccination. Neurology 2013, 80, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Ambati, A.; Lin, L.; Bonvalet, M.; Partinen, M.; Ji, X.; Maecker, H.T.; Mignot, E.J. Autoimmunity to hypocretin and molecular mimicry to flu in type 1 narcolepsy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E12323–E12332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, N.W.; Holm, A.; Kristensen, N.P.; Bjerregaard, A.M.; Bentzen, A.K.; Marquard, A.M.; Tamhane, T.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Ullum, H.; Jennum, P.; et al. CD8(+) T cells from patients with narcolepsy and healthy controls recognize hypocretin neuron-specific antigens. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard-Valnet, R.; Yshii, L.; Quériault, C.; Nguyen, X.H.; Arthaud, S.; Rodrigues, M.; Canivet, A.; Morel, A.L.; Matthys, A.; Bauer, J.; et al. CD8 T cell-mediated killing of orexinergic neurons induces a narcolepsy-like phenotype in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10956–10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latorre, D.; Kallweit, U.; Armentani, E.; Foglierini, M.; Mele, F.; Cassotta, A.; Jovic, S.; Jarrossay, D.; Mathis, J.; Zellini, F.; et al. T cells in patients with narcolepsy target self-antigens of hypocretin neurons. Nature 2018, 562, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetkovic-Lopes, V.; Bayer, L.; Dorsaz, S.; Maret, S.; Pradervand, S.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Lecendreux, M.; Lammers, G.J.; Donjacour, C.E.; Du Pasquier, R.A.; et al. Elevated Tribbles homolog 2-specific antibody levels in narcolepsy patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.S.; Volkmuth, W.; Duca, J.; Corti, L.; Pallaoro, M.; Pezzicoli, A.; Karle, A.; Rigat, F.; Rappuoli, R.; Narasimhan, V.; et al. Antibodies to influenza nucleoprotein cross-react with human hypocretin receptor 2. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 294ra105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, M.; Lin, L.; Kushida, C.A.; Umetsu, D.T.; Taheri, S.; Einen, M.; Mignot, E. Report of a case of immunosuppression with prednisone in an 8-year-old boy with an acute onset of hypocretin-deficiency narcolepsy. Sleep 2003, 26, 809–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, F.M.; Pradella-Hallinan, M.; Alves, G.R.; Bittencourt, L.R.; Tufik, S. Report of two narcoleptic patients with remission of hypersomnolence following use of prednisone. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2007, 65, 336–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Black, J.; Call, P.; Mignot, E. Late-onset narcolepsy presenting as rapidly progressing muscle weakness: Response to plasmapheresis. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 489–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Carlander, B.; Rivier, F.; Touchon, J.; Tafti, M. Successful management of cataplexy with intravenous immunoglobulins at narcolepsy onset. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 56, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecendreux, M.; Berthier, J.; Corny, J.; Bourdon, O.; Dossier, C.; Delclaux, C. Intravenous Immunoglobulin Therapy in Pediatric Narcolepsy: A Nonrandomized, Open-Label, Controlled, Longitudinal Observational Study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkanen, T.; Alén, R.; Partinen, M. Transient Impact of Rituximab in H1N1 Vaccination-associated Narcolepsy With Severe Psychiatric Symptoms. Neurologist 2016, 21, 85–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasling, P.; Malmeström, C.; Blennow, K. CSF orexin-A levels after rituximab treatment in recent onset narcolepsy type 1. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 6, e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donjacour, C.E.; Lammers, G.J. A remarkable effect of alemtuzumab in a patient suffering from narcolepsy with cataplexy. J. Sleep Res. 2012, 21, 479–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallweit, U.; Bassetti, C.L.A.; Oberholzer, M.; Fronczek, R.; Béguin, M.; Strub, M.; Lammers, G.J. Coexisting narcolepsy (with and without cataplexy) and multiple sclerosis: Six new cases and a literature review. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 2071–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabbal, S.; Fahn, S.; Frucht, S. Fetal tissue transplantation [correction of transplanation] in Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1998, 11, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, K.C.; Song, B.; Lee, N.; Jung, J.H.; Cha, Y.; Leblanc, P.; Neff, C.; Kong, S.W.; Carter, B.S.; Schweitzer, J.; et al. Pluripotent stem cell-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease: Current status and future prospects. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018, 168, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Carrión, O.; Murillo-Rodríguez, E. Effects of hypocretin/orexin cell transplantation on narcoleptic-like sleep behavior in rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Thankachan, S.; Kaur, S.; Begum, S.; Blanco-Centurion, C.; Sakurai, T.; Yanagisawa, M.; Neve, R.; Shiromani, P.J. Orexin (hypocretin) gene transfer diminishes narcoleptic sleep behavior in mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Blanco-Centurion, C.; Konadhode, R.; Begum, S.; Pelluru, D.; Gerashchenko, D.; Sakurai, T.; Yanagisawa, M.; van den Pol, A.N.; Shiromani, P.J. Orexin gene transfer into zona incerta neurons suppresses muscle paralysis in narcoleptic mice. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 6028–6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Centurion, C.; Liu, M.; Konadhode, R.; Pelluru, D.; Shiromani, P.J. Effects of orexin gene transfer in the dorsolateral pons in orexin knockout mice. Sleep 2013, 36, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, S.; Mochizuki, T.; Lops, S.N.; Ko, B.; Clain, E.; Clark, E.; Yamamoto, M.; Scammell, T.E. Orexin gene therapy restores the timing and maintenance of wakefulness in narcoleptic mice. Sleep 2013, 36, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Blanco-Centurion, C.; Konadhode, R.R.; Luan, L.; Shiromani, P.J. Orexin gene transfer into the amygdala suppresses both spontaneous and emotion-induced cataplexy in orexin-knockout mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2016, 43, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirogi, R.; Shinde, A.; Goyal, V.K.; Ravula, J.; Benade, V.; Jetta, S.; Pandey, S.K.; Subramanian, R.; Chowdary Palacharla, V.R.; Mohammed, A.R.; et al. Samelisant (SUVN-G3031), a histamine 3 receptor inverse agonist: Results from the phase 2 double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study for the treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in adult patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2024, 124, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, Y.; Mayer, G.; Kotterba, S.; Benes, H.; Burghaus, L.; Koch, A.; Girfoglio, D.; Setanoians, M.; Kallweit, U. Solriamfetol real world experience study (SURWEY): Initiation, titration, safety, effectiveness, and experience during follow-up for patients with narcolepsy from Germany. Sleep Med. 2023, 103, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogan, R.K.; Thorpy, M.J.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Partinen, M.; Del Rio Villegas, R.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Skowronski, R.; Tang, L.; Skobieranda, F.; Šonka, K. Efficacy and safety of calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium oxybates (lower-sodium oxybate [LXB]; JZP-258) in a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized withdrawal study in adults with narcolepsy with cataplexy. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa206, Erratum in: Sleep 2021, 44, zsab033; Erratum in: Sleep 2021, 44, zsab188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kushida, C.A.; Shapiro, C.M.; Roth, T.; Thorpy, M.J.; Corser, B.C.; Ajayi, A.O.; Rosenberg, R.; Roy, A.; Seiden, D.; Dubow, J.; et al. Once-nightly sodium oxybate (FT218) demonstrated improvement of symptoms in a phase 3 randomized clinical trial in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep 2022, 45, zsab200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Symptom | Treatment | AASM (2021) | EAN/ESRS (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDS | Modafinil | Strong | Strong |

| Armodafinil | Conditional | Weak | |

| Pitolisant | Strong | Strong | |

| Sodium Oxybate | Strong | Strong | |

| Solriamfetol | Strong | Strong | |

| Methylphenidate | Conditional | Weak | |

| Dextroamphetamine/Amphetamine derivatives | Conditional | Weak | |

| Cataplexy | Sodium Oxybate | Strong | Strong |

| Pitolisant | Strong | Weak | |

| Antidepressants (e.g., Venlafaxine, Clomipramine, Fluoxetine, Citalopram) | Not recommended | Strong | |

| DNS | Sodium Oxybate | Not mentioned | Strong |

| SP/HH | Pitolisant | Not mentioned | Weak |

| Sodium Oxybate | Not mentioned | Weak | |

| Antidepressants * | Not mentioned | Weak |

| Symptom | Treatment | AASM2021 | EAN/ESRS2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDS | Modafinil | Conditional | Weak |

| Sodium Oxybate | Conditional | Strong | |

| Pitolisant | Not recommended | Weak | |

| Methylphenidate | Not recommended | Weak | |

| Dextroamphetamine | Not recommended | Weak | |

| Cataplexy | Sodium Oxybate | Conditional | Strong |

| Pitolisant | Not recommended | Weak | |

| Antidepressants * | Not recommended | Weak | |

| DNS | Sodium Oxybate | Not mentioned | Weak |

| SP/HH | Sodium Oxybate | Not mentioned | Weak |

| Antidepressants * | Not mentioned | Weak |

| Drug | Daily Dosage Range | Dosing Schedule | Tmax (h) | t½ (h) | Mechanism of Action | Abuse Potential | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | 100–400 mg | Initial: 100–200 mg once daily; may increase weekly by 100 mg up to 400 mg, once or divided | 2–4 | 15 | Weak DAT inhibitor | Low | FDA: Approved; EMA: Approved |

| Armodafinil | 100–250 mg | Initial: 50–150 mg once daily; may increase weekly by 50 mg up to 250 mg, once or divided | 2 | ~15 | Weak DAT inhibitor | Low | FDA: Approved EMA: No |

| Pitolisant | 9–36 mg | Initial: 8.9 mg daily for 1 week, then 17.8 mg; max 35.6 mg; CYP2D6 poor metabolizers: half max dose | 3.5 | ~20 | H3-receptor antagonist/inverse agonist | Low | FDA: Approved EMA: No |

| Sodium Oxybate (IR) | 4.5–9 g/night (containing 820–1640 mg sodium) | Initiate dosage at 4.5 g/night orally, divided into two doses (at bedtime and 2.5 to 4 h later); titrate 1.5 g per night at weekly intervals; Recommended dosage: 6 g to 9 g/night. | 0.5–1.25 | 0.5–1 | GABA modulator | High | FDA: Approved EMA: Approved |

| Low-Sodium Oxybate | 4.5–9 g/night (containing 87–131 mg sodium) | Initiate dosage at 4.5 g/night orally, divided into two doses (at bedtime and 2.5 to 4 h later); titrate 1.5 g per night at weekly intervals; Recommended dosage: 6 g to 9 g/night. | 1.3 | 0.67 | GABA modulator | High | FDA: Approved EMA: No |

| Once-Nightly Oxybate | 4.5–9 g/night (containing 820-1640mg sodium) | Initiate dosage at 4.5 g once per night orally; titrate to effect in increments of 1.5 g per night at weekly intervals; Recommended dosage range: 6 g to 9 g once/night orally. | 1.5 | 0.5–1 | GABA modulator | High | FDA: Approved EMA: No |

| Solriamfetol | 75–150 mg | Initial: 75 mg once daily; may increase every ≥3 days to 150 mg | 2 | ~7.1 | DAT and NET inhibitor | Moderate | FDA: Approved EMA: No |

| Methylphenidate | 10–60 mg | Initial: 10 mg twice daily; may increase weekly by 5–10 mg; max 60 mg in 2–3 divided doses | 1–14 | 2–7 | DAT inhibitor | Moderate–High | FDA: Approved EMA: Approved |

| Dextroamphetamine | 5–60 mg | Initial: 10 mg once daily; may increase weekly by 10 mg; max 60 mg once daily or divided | IR: 3, ER: 8 | ~12 | DAT and NET inhibitor | High | FDA: No EMA: Approved |

| Drug | Daily Dosage Range | Dosing Schedule (Oral) | Tmax (h) | t½ (h) | Mechanism of Action | Abuse Potential | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modafinil | 50–400 mg | <30 kg: Start 100 mg daily, max 300 mg; ≥30 kg: Start 100 mg daily, max 400 mg; may divide doses | 2~4 * | 15 * | Weak DAT inhibitor | Low | FDA: No EMA: No |

| Sodium Oxybate (IR) | 2–9 g/night, based on body weight | Pediatric patients 7 years and older weighing at least 20 kg. The recommended starting dosage, titration regimen, and maximum total nightly dosage are based on body weight, divided into two doses (at bedtime and 2.5 to 4 h later). | 0.5–1.25 * | 0.5–1 * | GABA modulator | High | FDA: ≥7yr †; EMA: No |

| Low-Sodium Oxybate | 2–9 g/night, based on body weight. | Pediatric patients 7 years and older weighing at least 20 kg. The recommended starting dosage, titration regimen, and maximum total nightly dosage are based on body weight, divided into two doses (at bedtime and 2.5 to 4 h later). | 1.3 * | 0.67 * | GABA modulator | High | FDA: ≥7yr †; EMA: No |

| Once-Nightly Oxybate | 4.5–9 g/ night | Pediatric patients 7 years and older weighing at least 45 kg. The recommended starting dosage is 4.5 g/night. Increase the dosage by 1.5 g/night at weekly intervals to the maximum recommended dosage of 9 g/night orally. | 1.5 * | 0.5–1 * | GABA modulator | High | FDA: ≥7yr †; EMA: No |

| Pitolisant | 4.5–36 mg | 25~40 kg: start 4.45 mg, max 17.8 mg; ≥40 kg: start 4.45 mg, max 35.6 mg; titrate over 3–4 weeks; CYP2D6 poor metabolizers: half max dose | 3.5 * | ~20 * | H3-receptor antagonist/inverse agonist | Low | FDA: ≥6yr; EMA: No |

| Methylphenidate | 10–40 mg (IR/ER) | Start 5 mg twice daily; max 60 mg/day; ER may replace IR once dose stabilized | 1–14 | 2–7 | DAT inhibitor | Moderate–High | FDA:No; EMA: No |

| Dextroamphetamine | 2.5–20 mg (divided) | Children 6–12 years: start 5 mg daily; max 60 mg; Adolescents: start 10 mg daily; max 60 mg; IR or ER formulations | IR: 3, ER: 8 | ~12 * | DAT and NET inhibitor | High | FDA: No; EMA: No |

| Intervention Category | Specific Measures | Target Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Therapy (EDS) | Scheduled short naps (15–20 min/nap, 2–3 times/day); Sleep extension therapy | Reduce EDS; improve daytime alertness |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Cognitive restructuring; Systematic desensitization (for cataplexy); Problem-solving | Improve functional cognition; manage emotional triggers; enhance treatment adherence |

| Physical Exercise | Daily regular exercise | Reduce EDS; regulate sleep–wake cycle; control body weight |

| Counseling | Patient education; Peer support | Improve symptom management skills; build confidence in coping with the disease |

| Family Support | Caregiver education; Parent-child support | Help caregivers manage the patient’s condition; alleviate psychological distress |

| Drug Name | Trial Phase | Trial ID | Date of Registration | Recruitment Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAK-861 | 3 | CTIS2024-511998-30-00 | 13 June 2024 | Not Recruiting |

| 3 | CTIS2023-508465-32-00 | 25 April 2024 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-002966-34-FI | 20 January 2023 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-002966-34-IT | 14 December 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | NL-OMON53780 | 12 December 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-002966-34-SE | 5 December 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-001654-38-NL | 5 December 2022 | Authorised | |

| 2 | NL-OMON53459 | 5 December 2022 | Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-002966-34-NO | 5 December 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-001654-38-SE | 18 November 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-001654-38-FI | 16 November 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-001654-38-NO | 28 October 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | EUCTR2022-001654-38-FR | 21 October 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | JPRN-jRCT2071210007 | 8 April 2022 | Not Recruiting | |

| TAK-994 | 2 | JPRN-jRCT2071210015 | 28 April 2021 | Not Recruiting |

| 2 | NCT04820842 | 26 March 2021 | Not recruiting | |

| 2 | JPRN-jRCT2080225083 | 21 February 2020 | Not Recruiting | |

| 2 | NCT04096560 | 18 September 2019 | Not recruiting | |

| ALKS 2680 | 2/3 | NCT06767683 | 6 January 2025 | Recruiting |

| 2 | NCT06555783 | 13 August 2024 | Recruiting | |

| 2 | NCT06358950 | 2 April 2024 | Not recruiting | |

| ORX750 | 2 | NCT07096674 | 2 July 2025 | Recruiting |

| 2 | NCT06752668 | 23 December 2024 | Recruiting | |

| TAK-360 | 2 | JPRN-jRCT2051250080 | 31 July 2025 | Recruiting |

| 2 | NCT06952699 | 23 April 2025 | Recruiting | |

| E2086 | 1 | NCT06462404 | 12 June 2024 | Not recruiting |

| Treatment Category | Representative Solution/Medication | Mechanism | Effect of Typical Case Studies | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-effect Immunotherapy | Corticosteroids (Prednisone, IVMP) | Inhibits the synthesis of inflammatory mediators and impairs the function of neutrophils, monocytes, and B/T cells. | 8-year-old male (onset 2 months ago): Prednisone 1 mg/kg/day for 3 weeks, with no improvement in EDS or sleep parameters [120]; | Effects were inconsistent, with mostly short-term improvements. CSF orexin-A levels remain unchanged. Long-term use carries numerous side effects (such as acne and dermatitis). |

| 2 adults with concomitant inflammatory conditions (inflammatory bowel disease, asthma): 40mg/day prednisone resulted in resolution of EDS and cataplexy (likely related to the central stimulatory effects of corticosteroids) [121]. | ||||

| Plasma Exchange (PLEX) | Clear circulating antibodies and cytokines | Only 1 case: 60-year-old female (onset 2 months prior): Symptoms improved by 80% after 5 days of PLEX treatment, but relapsed 3 days later; subsequent IVIG treatment was ineffective [122]. | The effect is short-lived with no long-term benefits. Only one case has been reported, rendering it of no value for broader application. | |

| Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) | Regulate immune balance and suppress autoimmune responses | Early intervention (within 1–4 months of onset): Some patients experience reduced drop attack frequency and improved EDS, though effects typically last only weeks to months [123]; | Heterogeneous efficacy (significant differences between children and adults), lack of randomized controlled trials, inability to confirm definitive therapeutic efficacy | |

| Non-randomized study (22 patients receiving IVIG vs. 30 patients receiving standard treatment): No significant difference observed, with evidence of a placebo effect (patients in the double-blind trial reported improvement with both IVIG and placebo) [124]. | ||||

| Targeted B/T Cell Therapy | Rituximab (anti-CD20, B-cell depletion) | Deplete mature B cells and suppress humoral immunity | 1 case of Post-Pandemrix NT1 with psychiatric symptoms: Symptoms improved in the short term (2 months), subsequent infusions were ineffective [125]; 1 case of a 28-year-old male: 5 treatments of 1000mg/6 months, subjective improvement in EDS but no change in syncope, CSF orexin-A progressively decreased [126]. | Irreversible neuronal loss, no sustained benefit after B-cell depletion, potential risk of infection |

| Alemtuzumab (anti-CD52, T-cell suppression) | Inhibiting CD4+ T cells may exert neuroprotective effects. | 1 Case: 79-year-old male (62-year history of NT1): cataplexy completely resolved during treatment; no change in other symptoms [127]. | Only 1 case reported, mechanism unclear (may involve neuroprotection rather than immunosuppression), lacks large-scale validation. | |

| Nalizumab (anti-α4 integrin) | Prevent T cells from entering the central nervous system | 1 case of a 21-year-old female (onset 3 months ago): Symptoms showed no improvement after IVIG treatment; CSF orexin-A decreased from 70 pg/mL to 17 pg/mL [128]. | Early intervention remains ineffective, likely due to extensive neuronal loss (neural cell loss reaches 80% by the onset of syncope), with a risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). |

| Study | Trial Design | Potential Biases | Methodological Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| OX2R agonists, TAK-994, Dauvilliers Y, 2023 [93] | Phase 2, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding; multicenter; NT1; 8-week treatment | 1. Early termination leading to incomplete data 2. Lack of independent external monitoring board 3. Risk of unblinding due to AEs | 1. Small sample size with high dropout rate 2. Short duration; long-term safety/efficacy unknown 3. No active comparator; limited generalizability to NT1 |

| OX2R agonists, TAK-861, Dauvilliers Y, 2025 [95] | Phase 2, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled; international multicenter; NT1; 8-week treatment | 1. Functional unblinding due to efficacy/side effects 2. Selection bias from liver disease exclusion 3. Recall bias in self-reported outcomes | 1. Small sample size (n = 112); limited subgroup power 2. Short duration; long-term data lacking 3. No active comparator; high dropout in assessments |

| OX2R agonists, The First Light Study, 2025 [96,97] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled; NT1; 12-week treatment + 4-week follow-up | 1. Selection bias due to HLA-DQB1*06:02 inclusion 2. Performance bias from TEAEs leading to unblinding 3. Detection bias in subjective endpoints | 1. Small sample size (n ≈ 167); reduced statistical power 2. Short duration; long-term assessment lacking 3. Limited global diversity in recruitment |

| OX2R agonists, The Radiant Light Study, 2025 [96,97] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled; NT1 with cataplexy; 12-week treatment + 4-week follow-up | 1. Selection bias due to strict inclusion criteria 2. Attrition bias from missing dropout data 3. Reporting bias in patient-reported outcomes | 1. Limited dose comparison (single active dose) 2. Short follow-up; long-term AEs not assessed 3. Reliance on conventional endpoints; lack of novel measures |

| Pitolisant Harmony III, Dauvilliers Y, 2019 [23] | Phase 3, open-label, single-arm, pragmatic; long-term; previously exposed patients | 1. Lack of blinding introducing performance/detection bias 2. Selection bias from prior exposure 3. High dropout due to perceived inefficacy | 1. No placebo/active comparator; causal inference limited 2. No objective sleep measures 3. Concomitant medications confound outcomes |

| Pitolisant Pediatric, Dauvilliers Y, 2023 [26] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled; children aged 6–17 years; NT1/NT2 | 1. Unblinding due to discernible AEs 2. Underestimated effect from concomitant medications 3. Recall bias in cataplexy reporting | 1. Short duration (8 weeks); long-term efficacy unknown 2. UNS endpoint not validated in pediatrics 3. Underpowered subgroup analyses |

| Pitolisant Real-World Interim, Giuseppe Plazzi, 2025 [25] | Prospective, non-interventional PASS; multicenter; Europe; long-term follow-up | 1. Selection bias from specialized centers 2. Reporting bias from patient/physician reports 3. Confounding by concomitant treatments | 1. No control/comparator group 2. High discontinuation/loss to follow-up 3. Unblinded design with observer bias |

| Solriamfetol Phase 3, Michael J, 2019 [32] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled; NT1/NT2; EDS; 12-week treatment | 1. High discontinuation in 300 mg group affecting interpretability 2. Prior stimulant use affecting baseline 3. Unblinding due to AEs | 1. Short duration; long-term data lacking 2. Not powered for cataplexy assessment 3. No active comparator; indirect comparisons |

| Solriamfetol Long-term, Malhotra, 2020 [35] | Phase 3, open-label extension with randomized withdrawal; narcolepsy/OSA; up to 52 weeks | 1. Open-label design introducing bias 2. Selection bias from prior trial completers 3. Unblinding during withdrawal phase | 1. No active comparator; comparative efficacy limited 2. Reliance on subjective measures without objective tests 3. Generalizability limited by exclusions |

| Solriamfetol SURWEY, Y Winter, 2023 [138] | Retrospective, non-interventional chart review; Germany; real-world; stratified subgroups | 1. Selection bias from stable dose completion 2. Reporting bias from unblinded outcomes 3. Recall bias from medical records | 1. Small sample size (n = 70); limited generalizability 2. No control group; causal inference limited 3. Variable follow-up and titration schedules |

| Sodium Oxybate Pediatric, Lecendreux, 2022 [48] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, randomized withdrawal; pediatric (7–16 years); NT1 with cataplexy | 1. Unblinding due to drug effects 2. Funding bias from sponsor 3. Reliance on subjective outcomes | 1. Small sample in younger age group 2. Open-label extension lacks placebo control 3. Post hoc analyses without multiplicity adjustment |

| Low-Sodium Oxybate (LXB) Phase 3, Bogan, 2021 [139] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal; adults; NT1 with cataplexy | 1. Selection bias from responder enrichment 2. Unblinding due to AEs differences 3. Withdrawal effects confounding outcomes | 1. No direct comparison with SXB 2. Short withdrawal period (2 weeks) 3. Limited cardiovascular assessment |

| Once-Nightly SXB (FT218) Phase 3, Kushida, 2022 [140] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled; NT1/NT2; multiple doses; 13-week treatment | 1. Attrition bias from higher discontinuation in active group 2. Unblinding due to known AEs 3. Concomitant stimulant use influencing EDS | 1. Capped cataplexy reporting underestimating effect 2. Placebo effect diluting treatment effect 3. Short duration; long-term data lacking |

| Low-Sodium Oxybate (LXB) Long-term, Bogan, 2023 [52] | Phase 3, RCT, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal; NT1; open-label extension | 1. Expectation bias from open-label periods 2. Attrition bias from differential dropout 3. Recall bias in AE reporting | 1. Open-label design affecting subjective outcomes 2. Small subgroup samples limiting power 3. No systematic AE timing assessment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhu, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L. A Comprehensive Review of Current and Emerging Treatments for Narcolepsy Type 1. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238444

Xu Q, Chen Y, Wang T, Zhu Q, Xu J, Zhang L. A Comprehensive Review of Current and Emerging Treatments for Narcolepsy Type 1. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238444

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Qinglin, Yigang Chen, Tiantian Wang, Qiongbin Zhu, Jiahui Xu, and Lisan Zhang. 2025. "A Comprehensive Review of Current and Emerging Treatments for Narcolepsy Type 1" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238444

APA StyleXu, Q., Chen, Y., Wang, T., Zhu, Q., Xu, J., & Zhang, L. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Current and Emerging Treatments for Narcolepsy Type 1. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8444. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238444