Association of Preoperative Linear MRI Measures with Domain-Specific Cognitive Change After Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

Study Design and Patient Selection

3. Data Collection

4. Statistical Analysis

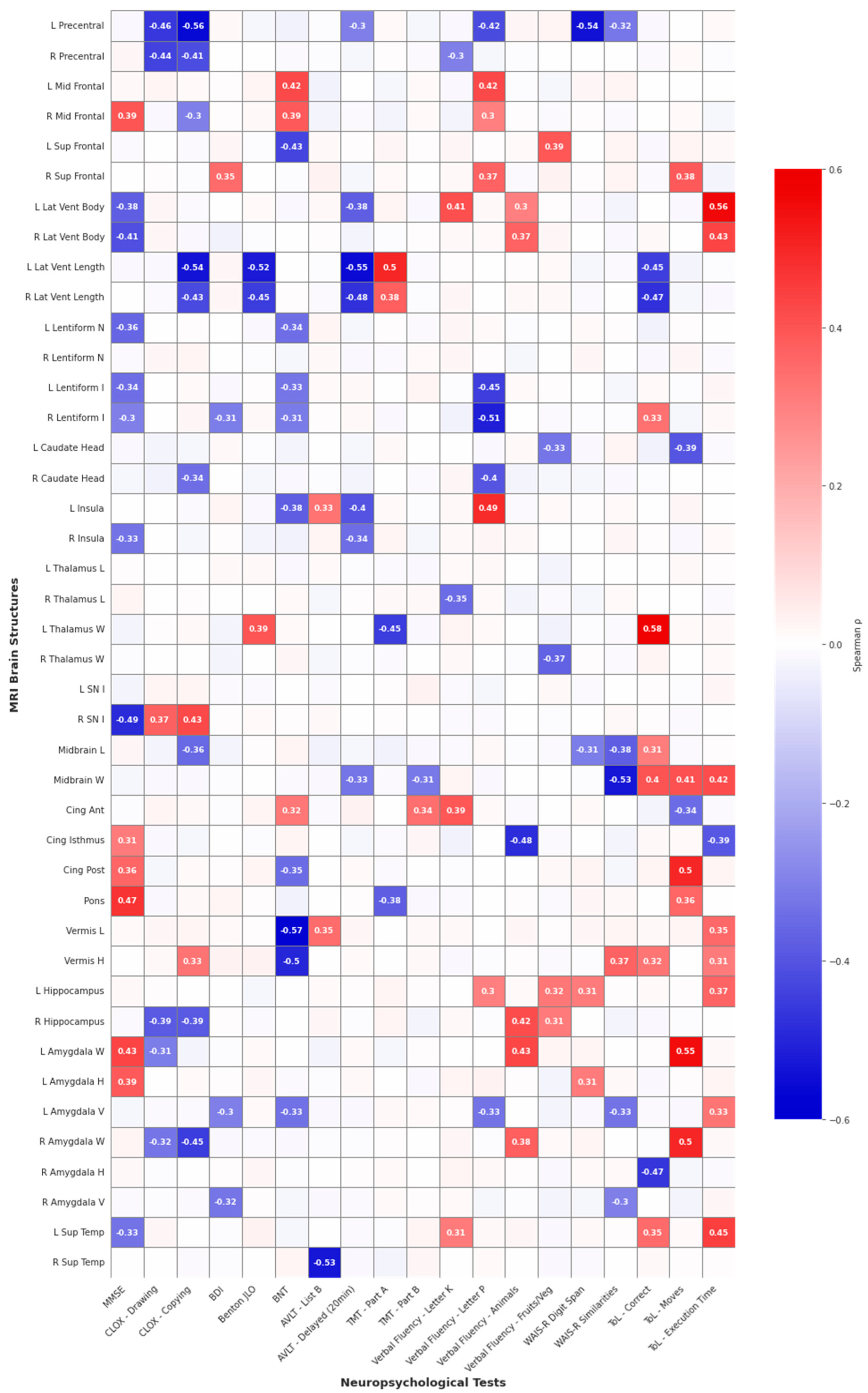

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. Patterns of Cognitive Change After STN-DBS

6.2. Morphometric Correlates of Postoperative Cognitive Outcome

6.3. Possible Mechanisms Underlying Cognitive Vulnerability

6.4. Clinical Implications for DBS Candidacy and Counseling

6.5. Motor Outcomes and Their Relation to Cognition

6.6. Limitations

6.7. Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rothlind, J.C.; York, M.K.; Carlson, K.; Luo, P.; Marks, W.J., Jr.; Weaver, F.M.; Stern, M.; Follett, K.; Reda, D.; CSP-468 Study Group. Neuropsychological changes following deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease: Comparisons of treatment at pallidal and subthalamic targets versus best medical therapy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rughani, A.; Schwalb, J.M.; Sidiropoulos, C.; Pilitsis, J.; Ramirez-Zamora, A.; Sweet, J.A.; Mittal, S.; Espay, A.J.; Martinez, J.G.; Abosch, A.; et al. Congress of Neurological Surgeons Systematic Review and Evidence-Based Guideline on Subthalamic Nucleus and Globus Pallidus Internus Deep Brain Stimulation for the Treatment of Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Executive Summary. Neurosurgery 2018, 82, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Witt, K.; Daniels, C.; Reiff, J.; Krack, P.; Volkmann, J.; Pinsker, M.O.; Krause, M.; Tronnier, V.; Kloss, M.; Schnitzler, A.; et al. Neuropsychological and psychiatric changes after deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: A randomised, multicentre study. Lancet Neurol. 2008, 7, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagonabarraga, J.; Corcuera-Solano, I.; Vives-Gilabert, Y.; Llebaria, G.; García-Sánchez, C.; Pascual-Sedano, B.; Delfino, M.; Kulisevsky, J.; Gómez-Ansón, B. Pattern of regional cortical thinning associated with cognitive deterioration in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Filippi, M.; Canu, E.; Donzuso, G.; Stojkovic, T.; Basaia, S.; Stankovic, I.; Tomic, A.; Markovic, V.; Petrovic, I.; Stefanova, E.; et al. Tracking Cortical Changes Throughout Cognitive Decline in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geevarghese, R.; Lumsden, D.E.; Costello, A.; Hulse, N.; Ayis, S.; Samuel, M.; Ashkan, K. Verbal Memory Decline following DBS for Parkinson’s Disease: Structural Volumetric MRI Relationships. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filoteo, J.V.; Reed, J.D.; Litvan, I.; Harrington, D.L. Volumetric correlates of cognitive functioning in nondemented patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, H.; Venneri, A. Cognitive and neuroanatomical correlates of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 356, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.B.; Junqué, C.; Martí, M.J.; Ramirez-Ruiz, B.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Tolosa, E. Structural brain correlates of verbal fluency in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroReport 2009, 20, 741–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; Junque, C.; Marti, M.J.; Tolosa, E. Brain structural MRI correlates of cognitive dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 310, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planche, V.; Munsch, F.; Pereira, B.; de Schlichting, E.; Vidal, T.; Coste, J.; Morand, D.; de Chazeron, D.; Derost, P.; Debilly, B.; et al. Anatomical predictors of cognitive decline after subthalamic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Brain Struct. Funct. 2018, 223, 3063–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kübler, D.; Wellmann, S.K.; Kaminski, J.; Skowronek, C.; Schneider, G.H.; Neumann, W.J.; Ritter, K.; Kühn, A. Nucleus basalis of Meynert predicts cognition after deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat Disord 2022, 94, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massano, J.; Garrett, C. Deep brain stimulation and cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease: A clinical review. Front. Neurol. 2012, 3, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Heo, J.H.; Lee, K.M.; Paek, S.H.; Kim, M.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Cho, S.Y.; Lim, Y.H.; Kim, M.R.; Jeong, S.Y.; et al. The effects of bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN DBS) on cognition in Parkinson disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2008, 273, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeding, H.M.; Speelman, J.D.; Huizenga, H.M.; Schuurman, P.R.; Schmand, B. Predictors of cognitive and psychosocial outcome after STN DBS in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2011, 82, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothlind, J.C.; York, M.K.; Luo, P.; Carlson, K.; Marks, W.J., Jr.; Weaver, F.M.; Stern, M.; Follett, K.A.; Duda, J.E.; Reda, D.J.; et al. Predictors of multi-domain cognitive decline following DBS for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 95, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defer, G.L.; Widner, H.; Marie, R.M.; Remy, P.; Levivier, M. Core assessment program for surgical interventional therapies in Parkinson’s disease (CAPSIT-PD). Mov. Disord. 1999, 14, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuschl, G.; Antonini, A.; Costa, J.; Śmiłowska, K.; Berg, D.; Corvol, J.C.; Fabbrini, G.; Ferreira, J.; Foltynie, T.; Mir, P.; et al. European Academy of Neurology/Movement Disorder Society-European Section Guideline on the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease: I. Invasive Therapies. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 1360–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romann, A.J.; Dornelles, S.; Maineri, N.L.; Rieder, C.R.M.; Olchik, M.R. Cognitive assessment instruments in Parkinson’s disease patients undergoing deep brain stimulation. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2012, 6, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biundo, R.; Calabrese, M.; Weis, L.; Facchini, S.; Ricchieri, G.; Gallo, P.; Antonini, A. Anatomical correlates of cognitive functions in early Parkinson’s disease patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeighami, Y.; Ulla, M.; Iturria-Medina, Y.; Dadar, M.; Zhang, Y.; Larcher, K.M.; Fonov, V.; Evans, A.C.; Collins, D.L.; Dagher, A. Network structure of brain atrophy in de novo Parkinson’s disease. eLife 2015, 4, e08440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, S.T.; Kaldenbach, M.A.; Antonini, A.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Timmermann, L.; Odin, P.; Katzenschlager, R.; Borgohain, R.; Fasano, A.; Stocchi, F.; et al. Levodopa Dose Equivalency in Parkinson’s Disease: Updated Systematic Review and Proposals. Mov. Disord. 2023, 38, 1236–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwary, A.; Mohite, D.; Omole, J.A.; Bhatti, K.S.; Khan, S. Is Deep Brain Stimulation Associated with Detrimental Effects on Cognitive Functions in Patients of Parkinson’s Disease? A Systematic Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Combs, H.L.; Folley, B.S.; Berry, D.T.; Segerstrom, S.C.; Han, D.Y.; Anderson-Mooney, A.J.; Walls, B.D.; van Horne, C. Cognition and Depression Following Deep Brain Stimulation of the Subthalamic Nucleus and Globus Pallidus Pars Internus in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2015, 25, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, S.K.; Conrad, A.; Konrad, P.E.; Neimat, J.S.; Davis, T.L. Ventricular width and complicated recovery following deep brain stimulation surgery. Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg. 2012, 90, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voruz, P.; Haegelen, C.; Assal, F.; Drapier, S.; Drapier, D.; Sauleau, P.; Vérin, M.; Péron, J.A. Motor Symptom Asymmetry Predicts Cognitive and Neuropsychiatric Profile Following Deep Brain Stimulation of the Subthalamic Nucleus in Parkinson’s Disease: A 5-Year Longitudinal Study. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2023, 38, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziunas, A.; Deltuva, V.P.; Tamasauskas, A.; Gleizniene, R.; Pranckeviciene, A.; Surkiene, D.; Bunevicius, A. Neuropsychiatric complications and neuroimaging characteristics after deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018, 14, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanganu, A.; Bedetti, C.; Degroot, C.; Mejia-Constain, B.; Lafontaine, A.-L.; Soland, V.; Chouinard, S.; Bruneau, M.-A.; Mellah, S.; Belleville, S.; et al. Mild cognitive impairment is linked with faster rate of cortical thinning in patients with Parkinson’s disease longitudinally. Brain 2014, 137, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lai, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Sun, B. A systematic review of brain morphometry related to deep brain stimulation outcome in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Park. Dis. 2022, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Pre-DBS Median [Q1, Q3] | Post-DBS Median [Q1, Q3] | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54 [48–62] | ||

| Gender (male/female) | 21/10 | ||

| PD duration (years) | 8.5 [7–10] | ||

| Follow-up interval (months) | 12 [6–12] | ||

| DBS one staged/two-staged bilateral procedure | 24/7 | ||

| UPDRS III ON | 6.0 [5.0, 9.5] | 5.0 [4.0, 7.0] | 0.159 |

| UPDRS III OFF | 35.0 [32.0, 43.5] | 37.0 [34.0, 46.0] | <0.001 * |

| LEDD | 1430.0 [1018.8, 1907.5] | 752.5 [505.0, 1131.2] | <0.001 * |

| Variable | n | Pre-DBS Median [Q1, Q3] | Post-DBS Median [Q1, Q3] | p Value | Cohen’s d | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 21 | 28.0 [28.0, 29.0] | 28.0 [27.0, 29.0] | 0.170 | −0.338 | Small |

| CLOX—Drawing | 22 | 13.0 [11.5, 14.0] | 12.5 [12.0, 13.0] | 0.170 | −0.336 | Small |

| CLOX—Copying | 22 | 14.0 [13.2, 15.0] | 14.0 [14.0, 14.8] | 0.805 | 0.046 | - |

| BDI | 28 | 12.5 [5.5, 18.2] | 9.5 [5.5, 13.2] | 0.186 | −0.295 | Small |

| Benton JLO | 25 | 24.0 [21.0, 28.0] | 25.0 [20.0, 29.0] | 0.484 | −0.159 | - |

| BNT | 22 | 14.0 [13.0, 15.0] | 14.0 [12.2, 14.8] | 0.041 * | −0.469 | Small |

| AVLT—Total (A/B) | 27 | 40.0 [34.5, 44.0] | 35.0 [31.5, 42.5] | 0.116 | −0.302 | Small |

| AVLT—A after 20 min | 27 | 7.0 [4.5, 8.5] | 5.0 [4.0, 7.0] | 0.088 | −0.330 | Small |

| TMT—Part A | 25 | 35.0 [30.0, 55.0] | 38.0 [29.0, 49.0] | 0.864 | −0.015 | - |

| TMT—Part B | 25 | 91.0 [78.0, 140.0] | 105.0 [72.0, 140.0] | 0.637 | 0.217 | Small |

| Verbal Fluency—Letter K | 26 | 17.0 [14.2, 19.0] | 14.0 [11.2, 16.8] | 0.004 * | −0.643 | Medium |

| Verbal Fluency—Letter P | 26 | 14.0 [12.0, 15.0] | 13.0 [10.2, 15.5] | 0.016 * | −0.490 | Small |

| Verbal Fluency—Animals | 28 | 20.0 [15.8, 23.2] | 17.5 [13.8, 19.0] | <0.001 * | −0.839 | Large |

| Verbal Fluency—Fruits/Vegetables | 25 | 19.0 [16.0, 21.0] | 17.0 [13.0, 20.0] | 0.027 * | −0.501 | Medium |

| WAIS-R—Digit Span | 25 | 10.0 [8.0, 12.0] | 9.0 [9.0, 11.0] | 0.277 | −0.222 | Small |

| WAIS-R—Similarities | 25 | 17.0 [13.0, 20.0] | 15.0 [13.0, 20.0] | 0.106 | −0.365 | Small |

| ToL—Correct Moves | 25 | 3.0 [2.0, 5.0] | 3.0 [2.0, 5.0] | 0.447 | −0.190 | - |

| ToL—Total Moves | 24 | 35.5 [22.2, 48.2] | 32.0 [21.8, 44.2] | 0.781 | 0.071 | - |

| ToL—Execution Time | 23 | 264.0 [186.0, 370.0] | 301.0 [196.0, 368.0] | 0.602 | −0.022 | - |

| Test | Vulnerable Structures (Negative Correlations) | Protective Structures (Positive Correlations) | Strongest Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Executive Functions | |||

| CLOX—Drawing | L/R Precentral gyrus | — | ρ = −0.46, p = 0.024 |

| CLOX—Copy | L Precentral gyrus, L/R Lateral ventricles (length), R Amygdala | R Substantia nigra | ρ = −0.56, p = 0.006 |

| ToL—Correct responses | L/R Lateral ventricles (length), R Amygdala (height) | L Thalamus, Midbrain | ρ = +0.58, p = 0.002 |

| ToL—Moves | — | L/R Amygdala, Posterior cingulate, Midbrain | ρ = +0.55, p = 0.005 |

| ToL—Total time | — | L/R Lateral ventricles (width), Midbrain, L Superior temporal | ρ = +0.56, p = 0.004 |

| Phonemic Fluency (Verbal Fluency: Letter P) | L Precentral gyrus, L/R Lentiform, R Caudate | L Middle frontal, L Insula, L Lateral ventricle (width), Anterior cingulate | ρ = −0.51, p = 0.008 |

| Memory Functions | |||

| AVLT—20 min Delayed | L/R Lateral ventricles (length), L Insula | — | ρ = −0.55, p = 0.003 |

| AVLT—List B | R Superior temporal | — | ρ = −0.53, p = 0.005 |

| WAIS-R Digit Span | L Precentral gyrus | — | ρ = −0.54, p = 0.005 |

| Attention and Processing Speed | |||

| TMT—Part A | L Thalamus | L Lateral ventricle (length) | ρ = −0.45, p = 0.023 |

| Visuospatial Functions | |||

| Benton JLO | L/R Lateral ventricles (length) | — | ρ = −0.52, p = 0.008 |

| Language Functions | |||

| Boston Naming Test | Cerebellar vermis (length and height), L Superior frontal | L Middle frontal | ρ = −0.57, p = 0.005 |

| Animal Naming | Cingulate isthmus | L/R Hippocampus, L/R Amygdala | ρ = +0.43, p = 0.023 |

| Fruit/Vegetable Naming | — | — | — |

| Global Cognitive Screening | |||

| MMSE | R Substantia nigra | Pons | ρ = −0.49, p = 0.023 |

| Abstract Reasoning | |||

| WAIS-R Similarities | Midbrain | — | ρ = −0.53, p = 0.007 |

| Affective/Emotional Functions | |||

| BDI | — | — | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szlufik, S.; Szałata, K.; Romaniuk, P.; Duszyńska-Wąs, K.; Karolak, M.; Drzewińska, A.; Mandat, T.; Ząbek, M.; Pasterski, T.; Raźniak, M.; et al. Association of Preoperative Linear MRI Measures with Domain-Specific Cognitive Change After Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238414

Szlufik S, Szałata K, Romaniuk P, Duszyńska-Wąs K, Karolak M, Drzewińska A, Mandat T, Ząbek M, Pasterski T, Raźniak M, et al. Association of Preoperative Linear MRI Measures with Domain-Specific Cognitive Change After Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238414

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzlufik, Stanisław, Karolina Szałata, Patryk Romaniuk, Karolina Duszyńska-Wąs, Magdalena Karolak, Agnieszka Drzewińska, Tomasz Mandat, Mirosław Ząbek, Tomasz Pasterski, Mikołaj Raźniak, and et al. 2025. "Association of Preoperative Linear MRI Measures with Domain-Specific Cognitive Change After Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238414

APA StyleSzlufik, S., Szałata, K., Romaniuk, P., Duszyńska-Wąs, K., Karolak, M., Drzewińska, A., Mandat, T., Ząbek, M., Pasterski, T., Raźniak, M., & Koziorowski, D. (2025). Association of Preoperative Linear MRI Measures with Domain-Specific Cognitive Change After Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8414. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238414