Risk Factors Associated with Corneal Nerve Fiber Length Reduction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Primary Aim

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Clinical and Laboratory Assessments

2.5. Vascular Assessments

2.6. Corneal and Ophthalmologic Evaluation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Normative Benchmarking

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Comparison with External Control Healthy Cohorts

3.3. Correlations with CNFL

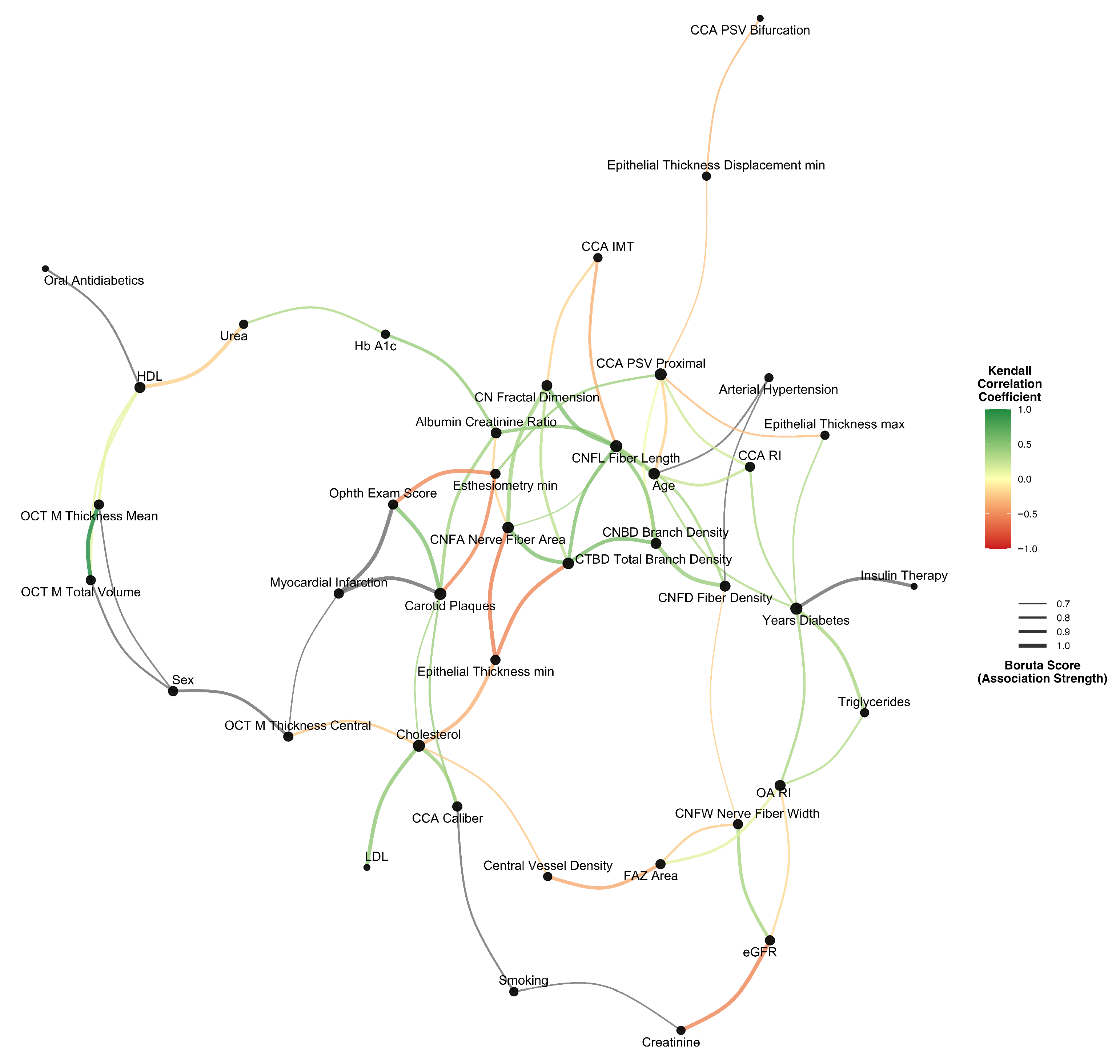

3.4. Multivariate Association Network

3.5. Linear Predictors

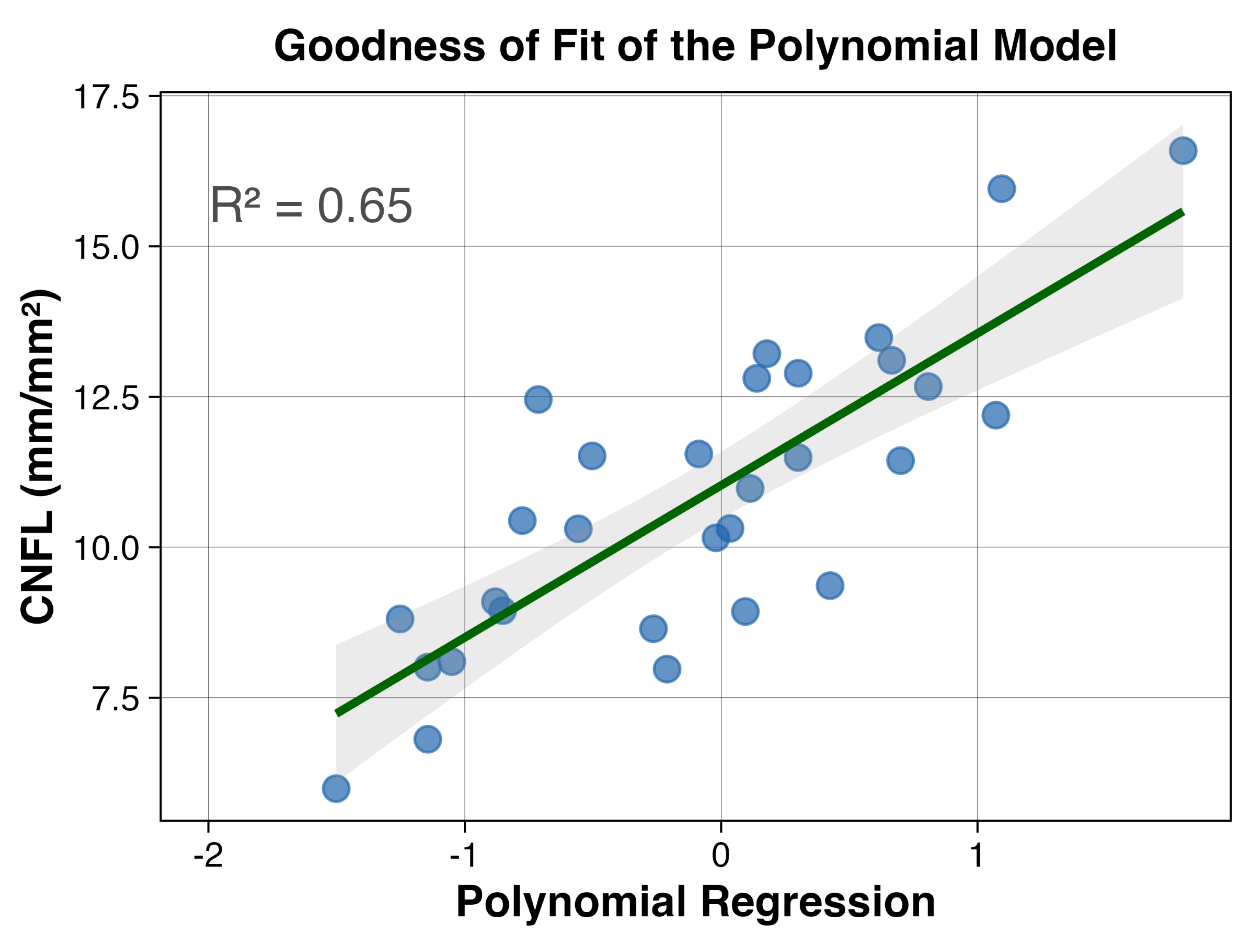

3.6. Non-Linear Interactions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNFL | Corneal nerve fiber length |

| DPN | Diabetic peripheral neuropathy |

| CCM | Corneal confocal microscopy |

| CCA | Common carotid artery |

| IMT | Intima-media thickness |

| OCT-A | Optical coherence tomography angiography |

| CVD | Central vessel density |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| OA | Ophthalmic artery |

| PSV | Peak systolic velocity |

| RI | Resistivity index |

| CNFrD | Corneal nerve fractal dimension |

| CNBD | Corneal nerve branch density |

| CTBD | Corneal total branch density |

| CNFA | Corneal nerve fiber area |

| CNFD | Corneal nerve fiber density |

| CNFW | Corneal nerve fiber width |

| CN | Corneal nerve |

| OCT-M | Macular optical coherence tomography |

| FAZ | Foveal avascular zone |

| GAM | Generalized additive models |

| EDV | End-diastolic velocity |

| DFE | Dilated fundus examination |

Appendix A

| Variable A | Variable B | Linear | Non-Parametric | Non-Linear |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | 0.52 [0.2–0.74] (p = 0.003) ** | 0.46 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.57 (p = 0.003) ** |

| Age | CCA PSV Proximal | −0.23 [−0.55–0.14] (p = 0.213) | −0.19 (p = 0.147) | 0.45 (p = 0.026) * |

| Age | CCA RI | 0.42 [0.07–0.68] (p = 0.022) * | 0.23 (p = 0.084) | 0.46 (p = 0.029) * |

| Age | Carotid Plaques | 0.42 [0.07–0.68] (p = 0.021) * | 0.33 (p = 0.026) * | 0.44 (p = 0.022) * |

| Age | Central Corneal Thickness | 0.41 [0.05–0.67] (p = 0.026) * | 0.25 (p = 0.06) | 0.39 (p = 0.098) |

| Age | Cholesterol | 0.35 [−0.01–0.63] (p = 0.059) | 0.29 (p = 0.025) * | 0.4 (p = 0.075) |

| Age | Corneal Thickness min | 0.39 [0.03–0.66] (p = 0.034) * | 0.23 (p = 0.083) | 0.38 (p = 0.119) |

| Age | Esthesiometry min | −0.39 [−0.66–−0.03] (p = 0.034) * | −0.3 (p = 0.03) * | 0.42 (p = 0.043) * |

| Age | FAZ Area | 0.41 [0.06–0.67] (p = 0.023) * | 0.28 (p = 0.033) * | 0.42 (p = 0.048) * |

| Age | Ophth Exam Score | 0.41 [0.06–0.67] (p = 0.023) * | 0.36 (p = 0.013) * | 0.49 (p = 0.01) * |

| Age | Triglycerides | 0.48 [0.15–0.72] (p = 0.007) ** | 0.3 (p = 0.021) * | 0.47 (p = 0.023) * |

| Age | Years Diabetes | 0.49 [0.16–0.72] (p = 0.006) ** | 0.32 (p = 0.017) * | 0.5 (p = 0.005) ** |

| Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | CCA Caliber | 0.26 [−0.11–0.57] (p = 0.158) | 0.26 (p = 0.045) * | 0.36 (p = 0.167) |

| Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | Carotid Plaques | 0.4 [0.05–0.66] (p = 0.028) * | 0.38 (p = 0.011) * | 0.46 (p = 0.016) * |

| Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | Epithelial Thickness max | 0.42 [0.07–0.68] (p = 0.022) * | 0.2 (p = 0.132) | 0.37 (p = 0.126) |

| Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | Esthesiometry min | −0.4 [−0.67–−0.05] (p = 0.027) * | −0.29 (p = 0.035) * | 0.41 (p = 0.052) |

| Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | Hb A1c | 0.37 [0.01–0.64] (p = 0.047) * | 0.42 (p = 0.001) ** | 0.48 (p = 0.015) * |

| Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | Ophth Exam Score | 0.4 [0.05–0.66] (p = 0.029) * | 0.35 (p = 0.015) * | 0.45 (p = 0.024) * |

| Albumin/Creatinine Ratio | Urea | 0.3 [−0.07–0.59] (p = 0.112) | 0.28 (p = 0.032) * | 0.41 (p = 0.059) |

| CCA Caliber | Carotid Plaques | 0.52 [0.19–0.74] (p = 0.003) ** | 0.42 (p = 0.005) ** | 0.51 (p = 0.008) ** |

| CCA Caliber | Cholesterol | 0.5 [0.17–0.73] (p = 0.005) ** | 0.4 (p = 0.003) ** | 0.54 (p = 0.003) ** |

| CCA IMT | CNBD Branch Density | −0.38 [−0.65–−0.03] (p = 0.037) * | −0.26 (p = 0.076) | 0.4 (p = 0.059) |

| CCA IMT | CNFL Fiber Length | −0.47 [−0.71–−0.13] (p = 0.009) ** | −0.35 (p = 0.011) * | 0.54 (p = 0.007) ** |

| CCA IMT | CN Fractal Dimension | −0.26 [−0.57–0.11] (p = 0.17) | −0.19 (p = 0.17) | 0.49 (p = 0.017) * |

| CCA PSV Proximal | Epithelial Thickness Displacement min | −0.45 [−0.69–−0.1] (p = 0.013) * | −0.25 (p = 0.054) | 0.44 (p = 0.054) |

| CCA PSV Proximal | Epithelial Thickness max | −0.4 [−0.67–−0.05] (p = 0.028) * | −0.28 (p = 0.033) * | 0.42 (p = 0.076) |

| CCA PSV Proximal | Esthesiometry min | 0.41 [0.06–0.67] (p = 0.024) * | 0.4 (p = 0.004) ** | 0.51 (p = 0.007) ** |

| CCA RI | OA RI | 0.42 [0.07–0.68] (p = 0.02) * | 0.32 (p = 0.018) * | 0.47 (p = 0.014) * |

| CCA RI | Ophth Exam Score | 0.41 [0.06–0.67] (p = 0.025) * | 0.29 (p = 0.043) * | 0.5 (p = 0.01) * |

| CCA RI | Years Diabetes | 0.4 [0.05–0.66] (p = 0.029) * | 0.33 (p = 0.016) * | 0.44 (p = 0.034) * |

| CNBD Branch Density | CNFA Nerve Fiber Area | 0.42 [0.06–0.67] (p = 0.022) * | 0.31 (p = 0.027) * | 0.42 (p = 0.053) |

| CNBD Branch Density | CNFD Fiber Density | 0.5 [0.17–0.73] (p = 0.005) ** | 0.42 (p = 0.005) ** | 0.6 (p = 0.003) ** |

| CNBD Branch Density | CNFL Fiber Length | 0.59 [0.29–0.78] (p = 0.001) ** | 0.46 (p = 0.001) ** | 0.6 (p < 0.001) *** |

| CNBD Branch Density | CN Fractal Dimension | 0.42 [0.07–0.68] (p = 0.02) * | 0.3 (p = 0.029) * | 0.45 (p = 0.029) * |

| CNBD Branch Density | CTBD Total Branch Density | 0.6 [0.31–0.79] (p < 0.001) *** | 0.55 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.63 (p = 0.001) ** |

| CNBD Branch Density | Epithelial Thickness min | −0.38 [−0.65–−0.02] (p = 0.04) * | −0.27 (p = 0.054) | 0.39 (p = 0.081) |

| CNFA Nerve Fiber Area | CNFL Fiber Length | 0.47 [0.13–0.71] (p = 0.009) ** | 0.37 (p = 0.005) ** | 0.49 (p = 0.016) * |

| CNFA Nerve Fiber Area | CN Fractal Dimension | 0.49 [0.15–0.72] (p = 0.006) ** | 0.37 (p = 0.004) ** | 0.5 (p = 0.013) * |

| CNFA Nerve Fiber Area | CTBD Total Branch Density | 0.62 [0.34–0.8] (p < 0.001) *** | 0.54 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.66 (p < 0.001) *** |

| CNFA Nerve Fiber Area | Epithelial Thickness min | −0.64 [−0.81–−0.37] (p < 0.001) *** | −0.57 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.74 (p < 0.001) *** |

| CNFA Nerve Fiber Area | LDL | 0.33 [−0.04–0.61] (p = 0.079) | 0.17 (p = 0.198) | 0.44 (p = 0.044) * |

| CNFD Fiber Density | CNFL Fiber Length | 0.42 [0.07–0.68] (p = 0.021) * | 0.35 (p = 0.012) * | 0.48 (p = 0.014) * |

| CNFD Fiber Density | CNFW Nerve Fiber Width | −0.37 [−0.64–−0.01] (p = 0.044) * | −0.21 (p = 0.131) | 0.42 (p = 0.05) |

| CNFD Fiber Density | CN Fractal Dimension | 0.47 [0.14–0.71] (p = 0.008) ** | 0.26 (p = 0.066) | 0.48 (p = 0.012) * |

| CNFD Fiber Density | Epithelial Thickness max | 0.37 [0.01–0.64] (p = 0.044) * | 0.28 (p = 0.05) | 0.43 (p = 0.039) * |

| CNFD Fiber Density | OCT M Thickness Mean | 0.36 [0–0.64] (p = 0.05) | 0.25 (p = 0.077) | 0.36 (p = 0.156) |

| CNFD Fiber Density | OCT M Total Volume | 0.36 [0–0.64] (p = 0.05) | 0.25 (p = 0.08) | 0.36 (p = 0.17) |

| CNFD Fiber Density | eGFR | −0.36 [−0.64–0] (p = 0.05) | −0.3 (p = 0.034) * | 0.4 (p = 0.071) |

| CNFL Fiber Length | CN Fractal Dimension | 0.6 [0.31–0.79] (p < 0.001) *** | 0.53 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.68 (p < 0.001) *** |

| CNFL Fiber Length | CTBD Total Branch Density | 0.59 [0.3–0.79] (p = 0.001) ** | 0.52 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.61 (p = 0.001) ** |

| CNFL Fiber Length | Epithelial Thickness min | −0.4 [−0.66–−0.05] (p = 0.029) * | −0.3 (p = 0.022) * | 0.43 (p = 0.054) |

| CNFW Nerve Fiber Width | FAZ Area | −0.3 [−0.6–0.06] (p = 0.102) | −0.22 (p = 0.09) | 0.47 (p = 0.026) * |

| CNFW Nerve Fiber Width | eGFR | 0.46 [0.13–0.71] (p = 0.01) * | 0.36 (p = 0.006) ** | 0.5 (p = 0.013) * |

| CN Fractal Dimension | CTBD Total Branch Density | 0.34 [−0.02–0.62] (p = 0.067) | 0.28 (p = 0.039) * | 0.45 (p = 0.031) * |

| CTBD Total Branch Density | Epithelial Thickness min | −0.74 [−0.87–−0.52] (p < 0.001) *** | −0.53 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.67 (p < 0.001) *** |

| Carotid Plaques | Cholesterol | 0.45 [0.11–0.7] (p = 0.012) * | 0.36 (p = 0.015) * | 0.48 (p = 0.009) ** |

| Carotid Plaques | Esthesiometry min | −0.62 [−0.8–−0.34] (p < 0.001) *** | −0.52 (p = 0.001) ** | 0.58 (p = 0.001) ** |

| Carotid Plaques | Ophth Exam Score | 0.62 [0.33–0.8] (p < 0.001) *** | 0.51 (p = 0.002) ** | 0.65 (p = 0.001) ** |

| Carotid Plaques | Triglycerides | 0.32 [−0.04–0.61] (p = 0.08) | 0.28 (p = 0.057) | 0.42 (p = 0.031) * |

| Central Corneal Thickness | Corneal Thickness min | 1 [1–1] (p < 0.001) *** | 0.95 (p < 0.001) *** | 1 (p < 0.001) *** |

| Central Corneal Thickness | CCA PSV Bifurcation | 0.37 [0.02–0.65] (p = 0.042) * | 0.17 (p = 0.192) | 0.47 (p = 0.026) * |

| Central Vessel Density | Cholesterol | −0.39 [−0.66–−0.03] (p = 0.033) * | −0.24 (p = 0.064) | 0.46 (p = 0.024) * |

| Central Vessel Density | Epithelial Thickness min | 0.39 [0.04–0.66] (p = 0.033) * | 0.28 (p = 0.034) * | 0.4 (p = 0.075) |

| Central Vessel Density | FAZ Area | −0.55 [−0.76–−0.24] (p = 0.001) ** | −0.37 (p = 0.003) ** | 0.58 (p = 0.004) ** |

| Central Vessel Density | OCT M Thickness Central | 0.26 [−0.11–0.57] (p = 0.169) | 0.26 (p = 0.048) * | 0.41 (p = 0.059) |

| Cholesterol | Epithelial Thickness min | −0.42 [−0.68–−0.07] (p = 0.021) * | −0.34 (p = 0.01) * | 0.5 (p = 0.009) ** |

| Cholesterol | Hb A1c | 0.32 [−0.05–0.61] (p = 0.088) | 0.31 (p = 0.019) * | 0.44 (p = 0.048) * |

| Cholesterol | LDL | 0.62 [0.34–0.8] (p < 0.001) *** | 0.46 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.65 (p = 0.001) ** |

| Cholesterol | Triglycerides | 0.35 [−0.01–0.63] (p = 0.055) | 0.31 (p = 0.017) * | 0.49 (p = 0.021) * |

| Corneal Thickness min | CCA PSV Bifurcation | 0.37 [0.01–0.65] (p = 0.043) * | 0.18 (p = 0.174) | 0.46 (p = 0.037) * |

| Creatinine | eGFR | −0.69 [−0.84–−0.44] (p < 0.001) *** | −0.54 (p < 0.001) *** | 0.69 (p < 0.001) *** |

| Creatinine | OCT M Thickness Central | 0.38 [0.02–0.65] (p = 0.04) * | 0.21 (p = 0.108) | 0.41 (p = 0.104) |

| Creatinine | CCA PSV Bifurcation | 0.13 [−0.24–0.47] (p = 0.483) | 0.25 (p = 0.053) | 0.45 (p = 0.042) * |

| Epithelial Thickness Displacement min | CCA PSV Bifurcation | −0.34 [−0.62–0.02] (p = 0.065) | −0.31 (p = 0.017) * | 0.43 (p = 0.064) |

| Epithelial Thickness max | Years Diabetes | 0.5 [0.17–0.73] (p = 0.005) ** | 0.32 (p = 0.017) * | 0.45 (p = 0.025) * |

| Epithelial Thickness min | Triglycerides | −0.4 [−0.66–−0.05] (p = 0.029) * | −0.25 (p = 0.064) | 0.41 (p = 0.083) |

| Esthesiometry min | Ophth Exam Score | −0.68 [−0.83–−0.42] (p < 0.001) *** | −0.52 (p = 0.001) ** | 0.63 (p < 0.001) *** |

| FAZ Area | Triglycerides | 0.42 [0.08–0.68] (p = 0.02) * | 0.2 (p = 0.129) | 0.4 (p = 0.109) |

| FAZ Area | Years Diabetes | 0.39 [0.04–0.66] (p = 0.033) * | 0.19 (p = 0.15) | 0.4 (p = 0.077) |

| FAZ Area | OCT M Thickness Central | −0.3 [−0.6–0.06] (p = 0.102) | −0.29 (p = 0.026) * | 0.44 (p = 0.07) |

| HDL | OCT M Thickness Mean | 0.4 [0.04–0.66] (p = 0.031) * | 0.09 (p = 0.475) | 0.43 (p = 0.062) |

| HDL | OCT M Total Volume | 0.4 [0.04–0.66] (p = 0.03) * | 0.1 (p = 0.464) | 0.43 (p = 0.056) |

| HDL | Triglycerides | −0.21 [−0.53–0.16] (p = 0.259) | −0.29 (p = 0.025) * | 0.47 (p = 0.033) * |

| HDL | Urea | −0.09 [−0.44–0.28] (p = 0.641) | −0.21 (p = 0.112) | 0.44 (p = 0.049) * |

| Hb A1c | Urea | 0.39 [0.03–0.66] (p = 0.034) * | 0.33 (p = 0.012) * | 0.47 (p = 0.03) * |

| OA RI | Triglycerides | 0.4 [0.05–0.67] (p = 0.027) * | 0.3 (p = 0.023) * | 0.48 (p = 0.016) * |

| OA RI | Years Diabetes | 0.46 [0.12–0.71] (p = 0.01) * | 0.35 (p = 0.009) ** | 0.46 (p = 0.02) * |

| OCT M Thickness Mean | OCT M Total Volume | 1 [1–1] (p < 0.001) *** | 1 (p < 0.001) *** | 1 (p < 0.001) *** |

| Ophth Exam Score | Urea | 0.41 [0.06–0.67] (p = 0.023) * | 0.3 (p = 0.037) * | 0.39 (p = 0.077) |

| Ophth Exam Score | Years Diabetes | 0.41 [0.06–0.67] (p = 0.024) * | 0.36 (p = 0.014) * | 0.43 (p = 0.034) * |

| Ophth Exam Score | OCT M Thickness Central | 0.42 [0.07–0.68] (p = 0.02) * | 0.19 (p = 0.177) | 0.41 (p = 0.037) * |

| Triglycerides | Years Diabetes | 0.46 [0.12–0.7] (p = 0.011) * | 0.35 (p = 0.008) ** | 0.49 (p = 0.012) * |

| Urea | OCT M Thickness Central | 0.44 [0.1–0.69] (p = 0.014) * | 0.15 (p = 0.246) | 0.43 (p = 0.05) |

| OCT M Thickness Central | CCA PSV Bifurcation | 0.12 [−0.25–0.46] (p = 0.518) | 0.3 (p = 0.022) * | 0.37 (p = 0.183) |

References

- Vinik, A.I.; Casellini, C.; Parson, H.K.; Colberg, S.R.; Nevoret, M.L. Cardiac autonomic neuropathy in diabetes: A predictor of cardiometabolic events. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.L.; Nave, K.A.; Jensen, T.S.; Bennett, D.L. New Horizons in Diabetic Neuropathy: Mechanisms, Bioenergetics, and Pain. Neuron 2017, 93, 1296–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop-Busui, R.; Boulton, A.; Feldman, E.; Bril, V.; Freeman, R.; Malik, R.; Sosenko, J.; Ziegler, D. Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2017, 40, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lazzarini, P.; McPhail, S.; van Netten, J.; Armstrong, D.; Pacella, R. Global disability burdens of diabetes-related lower-extremity complications in 1990 and 2016. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catrina, E.; Botezatu, I.; Bugă, C.; Popescu, R.; Zaharia, R. Piciorul Diabetic—Ghid de Practică Medicală; Editura Orizonturi—București: Bucharest, Romania, 2020; ISBN 978-973-736-422-7. [Google Scholar]

- Petropoulos, I.N.; Ponirakis, G.; Khan, A.; Gad, H.; Almuhannadi, H.; Brines, M.; Cerami, A.; Malik, R.A. Corneal confocal microscopy: Ready for prime time. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2020, 103, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, I.N.; Manzoor, T.; Morgan, P.; Fadavi, H.; Asghar, O.; Alam, U.; Ponirakis, G.; Dabbah, M.A.; Chen, X.; Graham, J.; et al. Repeatability of in vivo corneal confocal microscopy to quantify corneal nerve morphology. Cornea 2013, 32, e83–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, I.N.; Kamran, S.; Li, Y.; Khan, A.; Ponirakis, G.; Akhtar, N.; Deleu, D.; Shuaib, A.; Malik, R.A. Corneal confocal microscopy: An imaging endpoint for axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 3677–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, D.; Papanas, N.; Zhivov, A.; Allgeier, S.; Winter, K.; Ziegler, I.; Brüggemann, J.; Strom, A.; Peschel, S.; Köhler, B.; et al. Early detection of nerve fiber loss by corneal confocal microscopy and skin biopsy in recently diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2454–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittrant, B.; Ayoub, H.; Brunswick, P. From Sudoscan to bedside: Theory, modalities, and application of electrochemical skin conductance in medical diagnostics. Front. Neuroanat. 2024, 18, 1454095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, B.A.; Lovblom, L.E.; Bril, V.; Scarr, D.; Ostrovski, I.; Orszag, A.; Edwards, K.; Pritchard, N.; Russell, A.; Malik, R.A.; et al. Corneal confocal microscopy: A non-invasive surrogate of nerve fibre damage and repair in diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 3208–3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, U.; Anson, M.; Meng, Y.; Preston, F.; Kirthi, V.; Jackson, T.; Nderitu, P.; Cuthbertson, D.; Malik, R.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Artificial Intelligence and Corneal Confocal Microscopy: The Start of a Beautiful Relationship. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, N.; Eaton, S.; Cotter, M.; Tesfaye, S. Vascular factors and metabolic interactions in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 1973–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama, H.; Yokota, Y.; Tada, J.; Kanno, S. Diabetic neuropathy is closely associated with arterial stiffening and thickness in Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2007, 24, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, H.; Economides, P.; Veves, A. The role of endothelial function on the foot. Microcirculation and wound healing in patients with diabetes. Clin. Podiatr. Med. Surg. 1998, 15, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G. Pathophysiology of Critical Leg Ischaemia. In Critical Leg Ischaemia; Dormandy, J., Stock, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, J.J.; Chen, F.K.; Brooks, A.M.; Davis, B.T.; Turner, A.W.; Davis, T.M.; Davis, W.A. Carotid Disease and Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Parameters in Type 2 Diabetes: The Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 3034–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Chan, E.; Sun, Z.; Wong, R.; Lok, J.; Szeto, S.; Chan, J.C.; Lam, A.; Tham, C.C.; Ng, D.S.; et al. Clinically relevant factors associated with quantitative optical coherence tomography angiography metrics in deep capillary plexus in patients with diabetes. Eye Vis. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 12. Retinopathy, Neuropathy, and Foot Care: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48, S252–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursa, M.B.; Rudnicki, W.R. Feature Selection with the Boruta Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, S.; Schielzeth, H. A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 4, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelldorfer, J.; Bühlmann, P.; Van de Geer, S. Estimation for high-dimensional linear mixed-effects models using ℓ-penalization. Scand. J. Stat. 2011, 38, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groll, A.; Tutz, G. Variable selection for generalized linear mixed models by L1-penalized estimation. Stat. Comput. 2014, 24, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, M.; Ferdousi, M.; Petropoulos, I.N.; Morris, J.; Rayman, G.; Ebenezer, P.; Kabakus, N.; Boulton, A.J.; Efron, N.; Malik, R.A. Normative Values for Corneal Nerve Morphology Assessed Using Corneal Confocal Microscopy: A Multinational Normative Data Set. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirapapaisan, C.; Thongsuwan, S.; Chirapapaisan, N.; Chonpimai, P.; Veeraburinon, A. Characteristics of Corneal Subbasal Nerves in Different Age Groups: An in vivo Confocal Microscopic Analysis. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 3563–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, J.W.; Pop-Busui, R. Diabetic neuropathy: Mechanisms, emerging treatments, and subtypes. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2014, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, C.; Pritchard, N.; Edwards, K.; Vagenas, D.; Russell, A.W.; Malik, R.A.; Efron, N. Natural History of Corneal Nerve Morphology in Mild Neuropathy Associated With Type 1 Diabetes: Development of a Potential Measure of Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2014, 55, 7982–7990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, M.; Lambiase, A. Neurotrophic factors and corneal nerve regeneration. Neural Regen. Res. 2017, 12, 1220–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladea, L.; Zemba, M.; Calancea, M.; Călţaru, M.; Dragosloveanu, C.; Coroleucă, R.; Catrina, E.; Brezean, I.; Dinu, V. Corneal Epithelial Changes in Diabetic Patients: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, B.C.; Cheng, H.T.; Stables, C.L.; Smith, A.L.; Feldman, E.L. Diabetic neuropathy: Clinical manifestations and current treatments. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, S.; Chaturvedi, N.; Eaton, S.E.; Ward, J.D.; Manes, C.; Ionescu-Tirgoviste, C.; Witte, D.R.; Fuller, J.H. Vascular risk factors and diabetic neuropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 25th Perc. | Median | 75th Perc. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.00 | 59.50 | 68.00 |

| Years with diabetes | 6.25 | 10.00 | 16.75 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.53 | 7.05 | 7.40 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 36.45 | 43.00 | 53.00 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 104.25 | 123.00 | 144.05 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 176.95 | 208.00 | 239.50 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 124.25 | 148.00 | 167.75 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 30.25 | 37.20 | 45.88 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.97 |

| Albumin/creatinine ratio | 4.64 | 7.45 | 15.07 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 73.42 | 89.00 | 97.07 |

| CCA caliber (mm) | 7.10 | 7.65 | 7.95 |

| CCA IMT (mm) | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.78 |

| CCA RI | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.77 |

| CCA PSV proximal (cm/s) | 71.75 | 86.00 | 97.50 |

| CCA PSV bifurcation (cm/s) | 68.25 | 78.00 | 87.75 |

| OA PSV (cm/s) | 38.25 | 41.50 | 46.75 |

| OA RI | 0.73 | 0.77 | 0.81 |

| Esthesiometry min | 2.25 | 3.00 | 4.00 |

| Corneal thickness min (m) | 535.25 | 555.50 | 575.75 |

| Epithelial thickness min (m) | 42.25 | 45.00 | 48.75 |

| Epithelial thickness max (m) | 56.25 | 60.00 | 63.75 |

| Central corneal thickness (mm) | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.58 |

| Epithelial thickness displacement min (m) | 1.80 | 2.20 | 3.20 |

| CNFD (fibers/mm2) | 12.50 | 18.75 | 25.00 |

| CNBD (branches/mm2) | 12.50 | 18.75 | 25.00 |

| CTBD (branches/mm2) | 25.00 | 31.25 | 48.43 |

| CNFA (mm2/mm2) | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| CNFW (mm) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| CN fractal dimension | 1.45 | 1.47 | 1.48 |

| OCT-M thickness mean (m) | 267.38 | 274.55 | 280.17 |

| OCT-M thickness central (m) | 181.50 | 204.00 | 218.00 |

| OCT-M total volume (mm3) | 7.56 | 7.76 | 7.92 |

| FAZ area (m2) | 239.71 | 331.12 | 387.33 |

| Central vessel density (%) | 16.56 | 19.05 | 24.30 |

| Pearson | Kendall’s Tau | Distance Corr. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNFrD | 0.6 [0.31–0.79], p < 0.001 | 0.53, p < 0.001 | 0.68, p < 0.001 |

| CTBD | 0.59 [0.3–0.79], p < 0.001 | 0.52, p < 0.001 | 0.61, p = 0.001 |

| CNBD | 0.59 [0.29–0.78], p < 0.001 | 0.46, p < 0.001 | 0.6, p < 0.001 |

| CNFA | 0.47 [0.13–0.71], p = 0.009 | 0.37, p = 0.005 | 0.49, p = 0.016 |

| CNFD | 0.42 [0.07–0.68], p = 0.021 | 0.35, p = 0.012 | 0.48, p = 0.014 |

| CCA IMT | −0.47 [−0.71–0.13], p = 0.009 | −0.35, p = 0.011 | 0.54, p = 0.007 |

| min. Epi. Thick. | −0.4 [−0.66–0.05], p = 0.029 | −0.3, p = 0.022 | 0.43, p = 0.054 |

| Analysis | Variables Selected | Key Finding | Distance Corr. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lambda ± 5 | 6 (stable) | All 6 predictors retained | 0.68, p < 0.001 |

| Lambda ± 10 | 5–7 | Nasal sensitivity unstable | 0.61, p = 0.001 |

| Leave-one-patient-out | 5–6 | Core 5 predictors always selected | 0.6, p < 0.001 |

| Bootstrap (n = 100) | 6 (95% of samples) | Vascular predictors most stable | 0.49, p = 0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ladea, L.; Dragosloveanu, C.M.D.; Coroleuca, R.; Brezean, I.; Catrina, E.L.; Nedelcu, D.E.; Vilcu, M.E.; Toma, C.V.; Georgevici, A.I.; Dinu, V. Risk Factors Associated with Corneal Nerve Fiber Length Reduction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238411

Ladea L, Dragosloveanu CMD, Coroleuca R, Brezean I, Catrina EL, Nedelcu DE, Vilcu ME, Toma CV, Georgevici AI, Dinu V. Risk Factors Associated with Corneal Nerve Fiber Length Reduction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238411

Chicago/Turabian StyleLadea, Lidia, Christiana M. D. Dragosloveanu, Ruxandra Coroleuca, Iulian Brezean, Eduard L. Catrina, Dana E. Nedelcu, Mihaela E. Vilcu, Cristian V. Toma, Adrian I. Georgevici, and Valentin Dinu. 2025. "Risk Factors Associated with Corneal Nerve Fiber Length Reduction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238411

APA StyleLadea, L., Dragosloveanu, C. M. D., Coroleuca, R., Brezean, I., Catrina, E. L., Nedelcu, D. E., Vilcu, M. E., Toma, C. V., Georgevici, A. I., & Dinu, V. (2025). Risk Factors Associated with Corneal Nerve Fiber Length Reduction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8411. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238411