Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD) for Emergency Airway Management: A Systematic Review of Evidence and Implementation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

2.8. Certainty of Evidence Assessment

3. Results

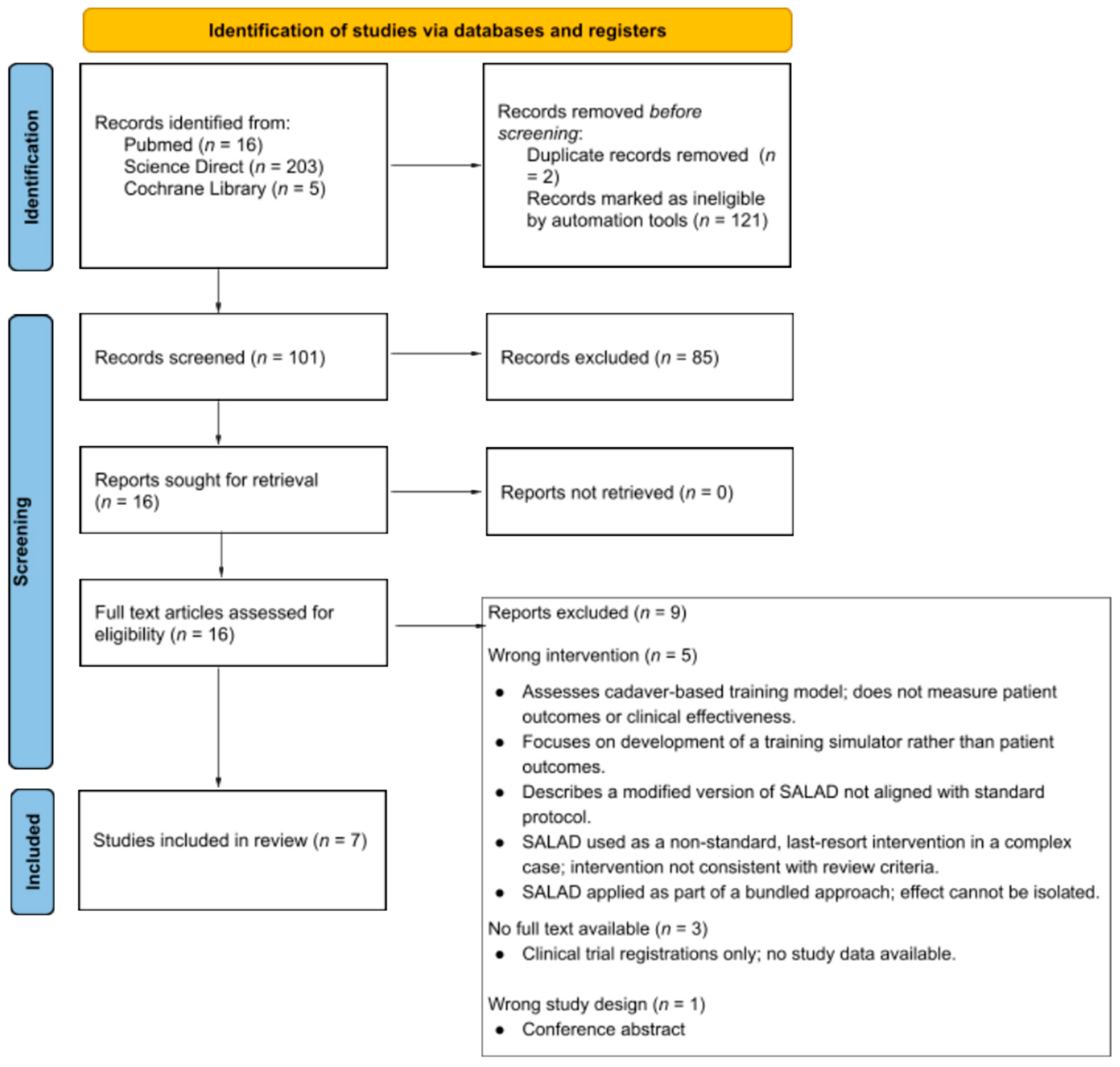

3.1. Study Selection Description

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Reporting Risk of Bias

3.4. Outcomes

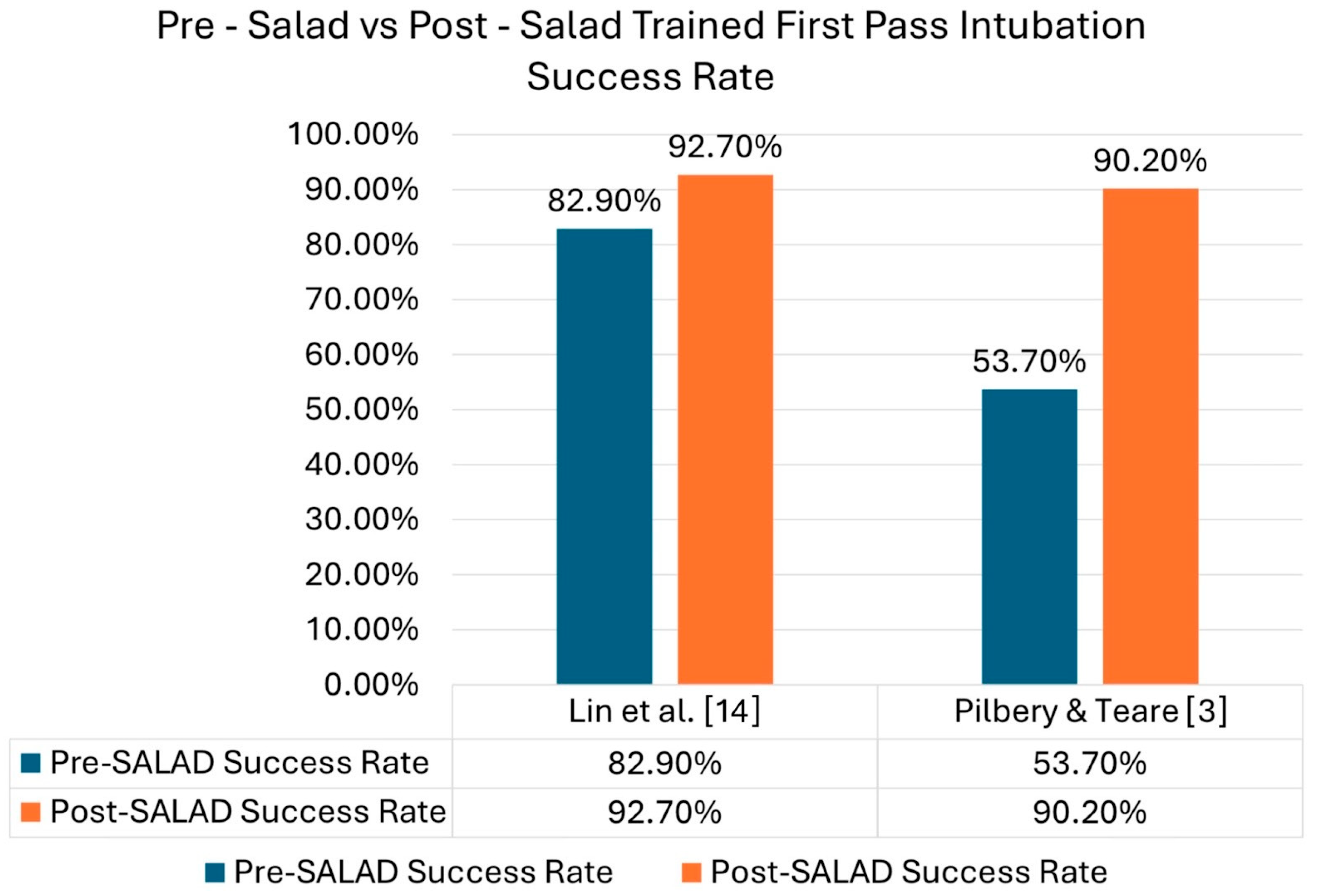

3.4.1. Primary Outcomes

Success Rate in Soiled Airways

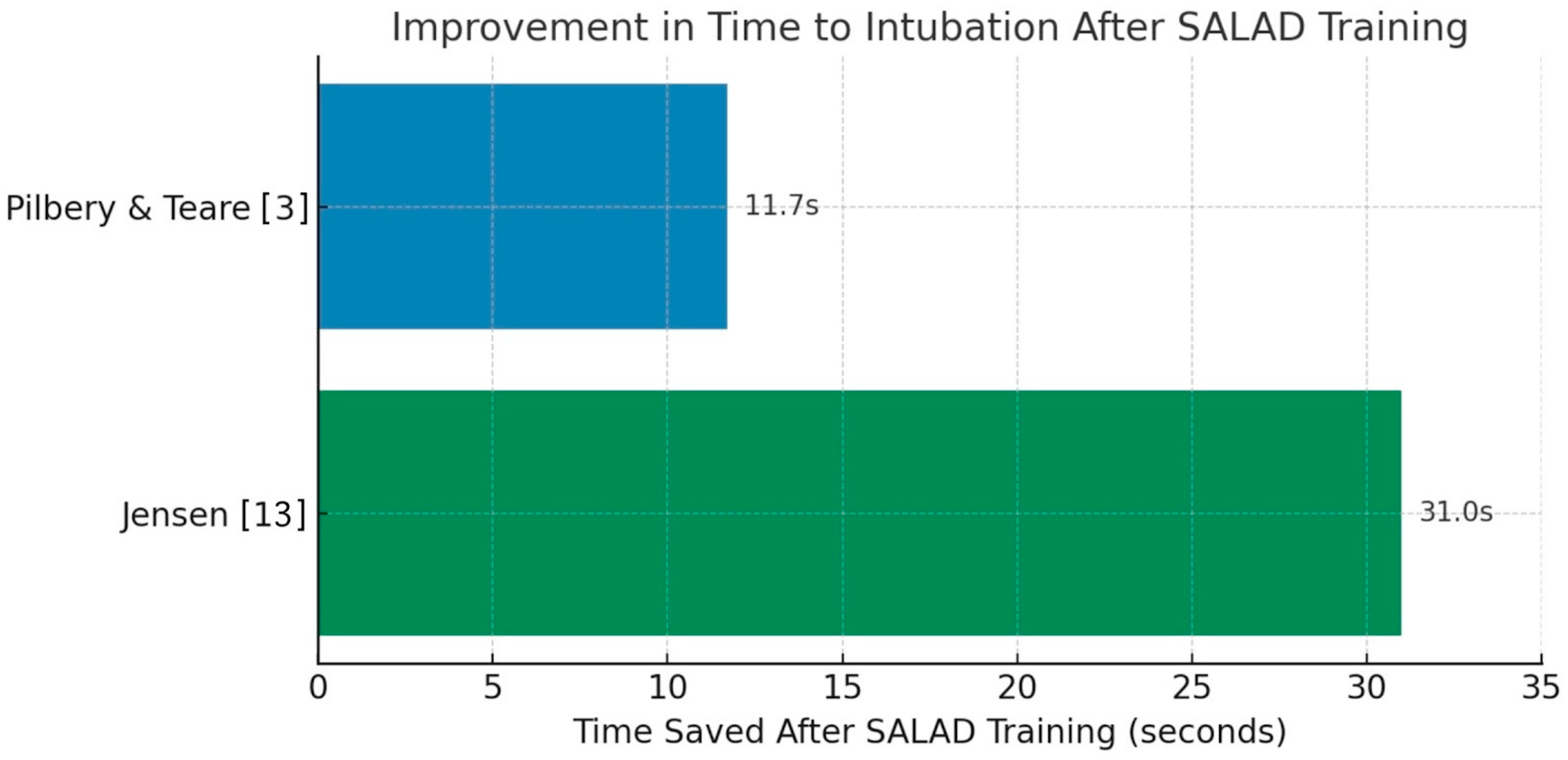

Time to Intubation

Visualization Quality

Aspirate Volume

Safety and Complications

3.4.2. Secondary Outcomes

Number of Attempts

Skill Retention

Provider Confidence

3.5. Certainty Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SALAD | Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination |

| ED | Emergency department |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| CAMT | Cadaveric airway management training |

| CICO | Can’t Intubate, Can’t Oxygenate |

| SATIATED | Soiled Airway Tracheal Intubation And The Effectiveness of Decontamination |

| RSC | Rigid Suction Catheter |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| ROB2 | Risk of Bias 2 |

| CARE checklist | Consequences, Alternatives, Reality, External factors |

| HEMS | Helicopter Emergency Medical Service |

| IEI | Intentional Esophageal Intubation |

References

- Goto, T.; Goto, Y.; Hagiwara, Y.; Okamoto, H.; Watase, H.; Hasegawa, K. Advancing emergency airway management practice and research. Acute Med. Surg. 2019, 6, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockey, D.J.; Coats, T.; Parr, M.J.A. Aspiration in severe trauma: A prospective study. Anaesthesia 1999, 54, 1097–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilbery, R.; Teare, M.D. Soiled airway tracheal intubation and the effectiveness of decontamination by paramedics (SATIATED): A randomised controlled manikin study. Br. Paramed. J. 2019, 4, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadason, K.; Root, C.; Boyle, J.; St George, J.; Ducanto, J. Modified cadaver technique to simulate contaminated airway scenarios to train medical providers in suction-assisted laryngoscopy and airway decontamination. AEM Educ. Train. 2024, 8, e10942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, C.W.; Pirotte, A.P.; DuCanto, J. Vomit, Blood, and Secretions: Dealing with the Contaminated Airway in Trauma. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2024, 14, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, C.W.; Mitchell, O.J.L.; Brown, R.; Evers, C.B.; Boyle, J.; Griffin, C.; West, F.M.; Gomm, E.; Miles, E.; McGuire, B.; et al. Suction Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD): A technique for improved emergency airway management. Resusc. Plus 2020, 1–2, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, T.; Amjad, M.A.; Cherian, S.V. Difficult Airway Management in the Intensive Care Unit: A Narrative Review of Algorithms and Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, G.; Kokori, E.; Aderinto, N.; Alsabri, M.A.H. Emergency airway management in resource limited setting. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, R. An Indigenous Suction-assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination Simulation System. Indian J. Crit. Care. Med. 2024, 28, 702–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, C.; Pauly, J.; Horner, J. Low-Cost Portable Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy Airway Decontamination (SALAD) Simulator for Dynamic Emesis. J. Educ. Teach. Emerg. Med. 2019, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.H.K.; Ko, S.; Wong, O.F.; Ma, H.M.; Lit, C.H.A.; Shih, Y.N. A manikin study comparing the performance of the GlideScope®, the Airtraq® and the C-MAC® in endotracheal intubation using suction-assisted laryngoscopy airway decontamination techniques in a simulated massive haematemesis scenario by emergency doctors. Hong Kong J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 28, 291–304. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, M.P.; Marmer, S.L.; Steuerwald, M.T.; Thompson, R.J.; Galgon, R.E. Three Airway Management Techniques for Airway Decontamination in Massive Emesis: A Manikin Study. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 20, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.; Barmaan, B.; Orndahl, C.M.; Louka, A. Impact of Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination Technique on Intubation Quality Metrics in a Helicopter Emergency Medical Service: An Educational Intervention. Air Med. J. 2020, 39, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.W.; Huang, C.C.; Ong, J.R.; Chong, C.F.; Wu, N.Y.; Hung, S.W. The suction-assisted laryngoscopy assisted decontamination technique toward successful intubation during massive vomiting simulation: A pilot before-after study. Medicine 2019, 98, e17898. [Google Scholar]

- DuCanto, J.; Serrano, K.D.; Thompson, R.J. Novel Airway Training Tool that Simulates Vomiting: Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy Assisted Decontamination (SALAD) System. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 18, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Guillote, C.P.; Root, C.W.; Braude, D.A.; Decker, C.A.; Romero, A.P.; Perez, N.E.; DuCanto, J.C. Prehospital SALAD Airway Technique in an Adolescent with Penetrating Trauma Case Report. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2024, 28, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Frantz, E.; Sarani, N.; Pirotte, A.; Jackson, B.S. Woman in respiratory distress. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2021, 2, e12344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, S.R.; Schroeder, D.C.; Ecker, H.; Böttiger, B.W.; Herff, H.; Wetsch, W.A. Comparing suction rates of novel DuCanto catheter against Yankauer and standard suction catheter using liquids of different viscosity—A technical simulation. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022, 22, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolla, D.A.; King, B.; Heslin, A.; Carlson, J.N. Comparison of Suction Rates Between a Standard Yankauer, a Commercial Large-Bore Suction Device, and a Makeshift Large-Bore Suction Device. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 61, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouleau, S.G.; Till, D.; Copperman, P.; Schandera, V.; Laurin, E.G. An intubation technique using hyperangulated video laryngoscopy and a DuCanto suction catheter preloaded with a bougie: A case report with a video demonstration. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorour, K.; Donovan, L. Intentional esophageal intubation to improve visualization during emergent endotracheal intubation in the context of massive vomiting: A case report. J. Clin. Anesth. 2015, 27, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornhall, D.K.; Almqvist, S.; Dolven, T.; Ytrebø, L.M. Intentional oesophageal intubation for managing regurgitation during endotracheal intubation. Anaesth. Intensive Care 2015, 43, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Primary Outcome | Pilbery et al. [3] | Fiore et al. [12] | Jensen et al. [13] | Lin et al. [14] | DuCanto et al. [15] | Guillote et al. [16] | Frantz et al. [17] | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to First-Pass Intubation ↓ | ✔ p < 0.001 | ✔ p < 0.05 | ✔ p < 0.001 | ✔ p = 0.031 | ✖ | ✔ (clinical case) | ✖ | Time to first-pass intubation significantly decreased. |

| Visualization Quality ↑ | ✔ p < 0.001 | ✔ (subjective, p < 0.05) | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ (subjective) | ✔ (subjective) | Airway visualization quality generally improved, though mostly subjective. |

| Aspirate Volume/Airway Contamination ↓ | ✔ p < 0.001 | ✔ (visual, p < 0.05) | ✖ | ✔ (visual, p < 0.001) | ✖ | ✔ (observed effective) | ✔(descriptive) | Consistently reduced airway contamination but objective measurement is rare. |

| Adverse Events Reported | ✖ (None) | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ (None) | ✖ (None) | No adverse events reported. |

| Success Rate in Soiled Airway ↑ | ✔ 97.4%, p < 0.001 | ✔ 97%, p < 0.05 | ✔ 100% post-training | ✔ 92.7%, p = 0.001 | ✖ (not assessed) | ✔ (1st pass, clinical) | ✖ | Success rate in soiled airways significantly improved. |

| Secondary Outcome | Pilbery at al. [3] | Fiore et al. [12] | Jensen et al. [13] | Lin et al. [14] | DuCanto et al. [15] | Guillote et al. [16] | Frantz et al. [17] | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Attempts ↓ | ✖ | ✔ (1 attempt) | ✔ (0 failures post) | ✔ (post-training) | ✖ | ✔ (1 attempt) | ✖ | The number of attempts decreased post-training. |

| Skill Retention at Follow-up ↑ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ (3-month retention) | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | ✖ | Skill retention evaluated by only one study but reported maintained performance at 3 months. |

| Confidence Improvement ↑ | ✖ | ✖ | ✔ (qualitative) | ✔ p < 0.05 | ✔ p < 0.05 | ✖ | ✖ | Confidence improved significantly. |

| Study Design (Majority) | ROB | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Effect (Direction) | Certainty of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-pass intubation success | |||||||

| Simulation (observational) | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Improves success rate | ⨁◯◯◯ Very Low |

| Time to Intubation | |||||||

| Simulation (observational) | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Reduced intubation time | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Visualization Quality | |||||||

| Simulation (observational) | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Improved visualization | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Aspirate Volume | |||||||

| Simulation (observational) | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Reduced contamination (qualitative) | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Adverse Events/ Complications | |||||||

| Case Reports | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Very serious | Not serious | No complications reported | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Number of Intubation Attempts | |||||||

| Simulation (observational) | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Fewer attempts post-training | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Skill Retention | |||||||

| Simulation (observational, 1 study) | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Very serious | Not serious | Maintained skills at 3 months | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

| Provider Confidence | |||||||

| Simulation (observational) | Serious | Not serious | Serious | Serious | Not serious | Confidence improved | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shaikh, S.; Hejazi, H.; Shaikh, S.; Sajid, A.; Shahab, R.; Deed, A.; Afnan, R.; Hashmi, A.; Sharieff, R.E.A.; Naureen, A.; et al. Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD) for Emergency Airway Management: A Systematic Review of Evidence and Implementation. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7430. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207430

Shaikh S, Hejazi H, Shaikh S, Sajid A, Shahab R, Deed A, Afnan R, Hashmi A, Sharieff REA, Naureen A, et al. Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD) for Emergency Airway Management: A Systematic Review of Evidence and Implementation. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(20):7430. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207430

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaikh, Saniyah, Hamad Hejazi, Safwaan Shaikh, Adeeba Sajid, Rida Shahab, Ayesha Deed, Rida Afnan, Anam Hashmi, Raiyan Ehtesham Ahmed Sharieff, Asfiya Naureen, and et al. 2025. "Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD) for Emergency Airway Management: A Systematic Review of Evidence and Implementation" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 20: 7430. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207430

APA StyleShaikh, S., Hejazi, H., Shaikh, S., Sajid, A., Shahab, R., Deed, A., Afnan, R., Hashmi, A., Sharieff, R. E. A., Naureen, A., & Ribeiro, M. A. F., Jr. (2025). Suction-Assisted Laryngoscopy and Airway Decontamination (SALAD) for Emergency Airway Management: A Systematic Review of Evidence and Implementation. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(20), 7430. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14207430