Abstract

We aimed to examine rates of COVID-19 vaccination to elucidate the need for targeted public health interventions. We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical files of all adults registered in a central district in Israel from 1 January 2021 to 31 March 2022. The population was characterized by vaccination status against COVID-19 and the number of doses received. Univariate and multivariable analyses were used to identify predictors of low vaccination rates that required targeted interventions. Of the 246,543 subjects included in the study, 207,911 (84.3%) were vaccinated. The minority groups of ultra-Orthodox Jews and Arabs had lower vaccination rates than the non-ultra-Orthodox Jews (68.7%, 80.5% and 87.7%, respectively, p < 0.001). Adults of low socioeconomic status (SES) had lower vaccination rates compared to those of high SES (74.4% vs. 90.8%, p < 0.001). Adults aged 20–59 years had a lower vaccination rate than those ≥60 years (80.0% vs. 92.1%, p < 0.0001). Multivariate analysis identified five independent variables that were significantly (p < 0.001) associated with low vaccination rates: minority groups of the ultra-Orthodox sector and Arab population, and underlying conditions of asthma, smoking and diabetes mellitus (odds ratios: 0.484, 0.453, 0.843, 0.901 and 0.929, respectively). Specific targeted public health interventions towards these subpopulations with significantly lower rates of vaccination are suggested.

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 [1]. This pandemic has caused huge morbidity and mortality rates all over the globe; as of 15 July 2022, the WHO had recorded nearly 558 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 6.4 million deaths [2]. In addition to the acute illness, COVID-19 can also cause long-term complications and morbidity. The long-term illness of COVID-19 (referred to as long COVID or post-acute COVID-19) includes pulmonary, cardiovascular, neurological, hematological, multisystem inflammatory, renal, endocrine, gastrointestinal and integumentary sequelae [3].

Vaccination against the causative agent, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is the leading strategy to control the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide [4]. A COVID-19 vaccine produced by Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) contains nucleoside-modified messenger RNA encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein [5]. Two doses of this vaccine given to healthy adults 21 days apart elicited high neutralizing titers and robust, antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses against the virus [6,7]. BNT162b2 was 95% effective in preventing COVID-19 from 7 days after the second dose [8,9]. On 11 December 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized the Pfizer-BioNTech for COVID-19 prevention in persons 16 years of age or older [10].

Because of waning immunity and the development of SARS-CoV-2 mutants, on 30 July 2021, Israel was the first country to make a third dose (“booster dose”) of the BNT162b2 Pfizer vaccine available to all individuals aged ≥60 years who had been vaccinated at least 5 months earlier [11]. Later on, the booster program was extended to all the population aged 12 years or older [11].

A large observational study conducted by Barda et al., using nationwide mass vaccination data in Israel, showed that a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine is effective in preventing severe COVID-19-related outcomes. Adding a third vaccine dose was estimated as being 93% effective in preventing COVID-19-related hospitalization, 92% in preventing severe disease, and 81% in preventing COVID-19-related death, as of ≥7 days after the third dose [12].

The aim of our study was to explore factors associated with low acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine in adults, in order to improve public health-targeted interventions in subpopulations with low vaccination rates. In this manuscript, we describe the study population and the methodology used and then report univariate and multivariate analyses of variables associated with vaccine acceptance.

2. Materials and Methods

Clalit Health Services (CHS) insures approximately 54% of the Israeli population. It maintains a comprehensive computerized database, continuously updated with regard to subjects’ demographics, community and outpatient visits, laboratory tests, hospitalizations, and medications prescribed and purchased. During each physician’s visit, a diagnosis is recorded according to the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9).

The study population consisted of all subjects aged ≥20 years who were registered with CHS during the study period of 1 January 2021 to 31 March 2022 within the Dan-Petach Tikva administrative district. This district comprises about 500,000 members and includes large towns of mainly secular Jews, large towns of ultra-Orthodox Jews, and few Arab towns, with the majority being the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish population. Israelis tend to live within neighborhoods based on this grouping.

The study population was divided into two groups: unvaccinated and vaccinated with at least one dose of the vaccine, with further subgroupings according to the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received. The data collected from the electronic database included demographic information (age, gender, sector, and socioeconomic status (SES), which was defined according to the classification of the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics [13]); vaccinations for COVID-19 (first, second and third dose) and for influenza in the previous three years; information regarding PCR testing (sampling dates and results); and comorbidities. The study was approved by the Clalit Community Institutional Review Board for Human Studies.

We extracted the study data into a central data table, which was anonymized for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to report the demographic and clinical variables of the vaccinated and unvaccinated study groups. Proportions were compared by a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, and continuous variables by Student’s t-test or a Mann–Whitney test, as appropriate. Variables associated with vaccine acceptance were first identified by univariate analysis. We then performed multivariate logistic regression to analyze the adjusted odds ratio of vaccination as the dependent variable, based on variables found significant in the univariate analysis. We drew vaccination uptake curves by sector adjusted for age and gender. We also drew a forest plot describing the adjusted relative association of the various variables on vaccine acceptance. Analysis was performed with R software (versions 4.1.0, Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org, accessed on 18 July 2022).

3. Results

Our study included all 246,542 adults aged ≥20 years from the Dan-Petach Tikva district. Of the study group, 125,819 (51%) were female and 120,724 (49%) males; 230,546 (93.5%) were Jews and 15,997 (6.5%) Arabs.

3.1. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance

Table 1 presents the characteristics of our study population by receiving/not receiving the COVID-19 vaccine. Of the 256,543 adults in our study group, 207,911 (84.3%) received at least a single dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Adults aged 20–59 years had a considerably lower vaccination rate than those aged ≥60 years (80.0% vs. 92.1%, p < 0.001). Males were less often vaccinated than females (83.6% vs. 85.0%, p < 0.001). The minority groups of ultra-Orthodox Jews and Arabs had lower vaccination rates than the non-ultra-Orthodox Jews (68.7%, 80.5%, and 87.7%, respectively, p < 0.001). Vaccination rates were also significantly related to SES: adults with low SES had lower vaccination rates compared to those with high SES (74.4% vs. 90.8%, p < 0.001). A higher COVID-19 vaccination rate was observed in adults who had received a previous seasonal influenza vaccine compared to those who did not (94.5% vs. 77.2%, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Study group variables by COVID-19 vaccination.

Table 2 presents vaccination rates by underlying medical conditions. In general, the percentage of patients with underlying medical conditions was higher among the vaccinated than the unvaccinated population. Among medical conditions that were associated with increased risk of severe COVID-19, smoking, asthma, Down syndrome, depression, and obesity had relatively low rates among vaccinated individuals (82.7%, 85.4%, 87.2%, 87.5%, and 88.1%, respectively) as opposed to adults with cardiac disease, hypertension, cystic fibrosis, biological therapy or after solid organ transplantation, who had a high rate of >90% (92.4%, 92.5%, 92.9%, 94.7%, and 95.3%, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Vaccination against COVID-19 by underlying medical conditions.

3.2. Analysis by Number of Vaccine Doses Received

Of the 207,911 adults who were vaccinated against COVID-19, 7.5% received only one single dose of the vaccine, 16.5% received two doses and 76% received the recommended three doses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of study group by the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received.

The rates of receiving the first, second, and third doses of the COVID-19 vaccine were very similar between females and males. The number of vaccine doses received was significantly age-related: three doses of the vaccine were received by only 63% of individuals aged 20–39 years, compared to 74% and >80% in those aged 40–59 and >60 years, respectively. In comparison to the whole population, a higher number of vaccine doses were significantly given to individuals with high SES, non-ultra-Orthodox Jews, and those previously vaccinated against influenza (p < 0.001 for these three variables) (Table 3).

Table 4 presents the number of vaccine doses given to adults with various underlying medical conditions. The lowest rates of receiving the third COVID-19 vaccine dose were among adults with the following comorbidities: hematologic diseases (64.7%), steroid therapy (65.5%), smoking (75.8%), asthma (76.1%), neurologic diseases (76.5%), Down syndrome (77.1%) and obesity (78.5%).

Table 4.

Characteristics of study group with underlying medical conditions by the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received.

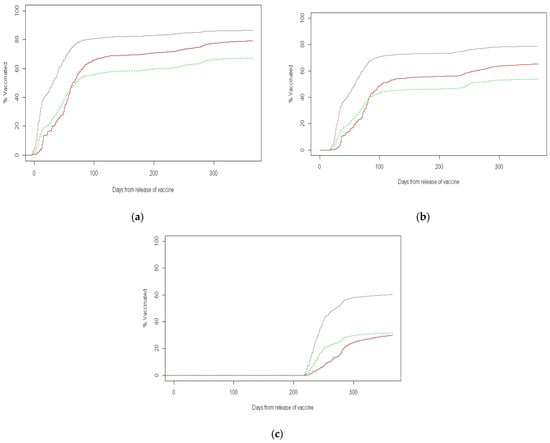

Figure 1a–c shows the accumulated percentages of the vaccination with time by sector and according to the number of vaccine doses received. The figure refers to the time period from the approval of the vaccine dose for adults by the Israeli Ministry of Health until 31 March 2022. The vaccination uptake was slowest among ultra-Orthodox Jews, relatively slow in the Arab population, and fastest among non-ultra-Orthodox Jews.

Figure 1.

Cumulative rate with the time of vaccinated adults by sector. (a) First COVID-19 vaccine uptake; (b) second COVID-19 vaccine uptake; (c) third COVID-19 vaccine uptake.

3.3. Multivariate Analysis

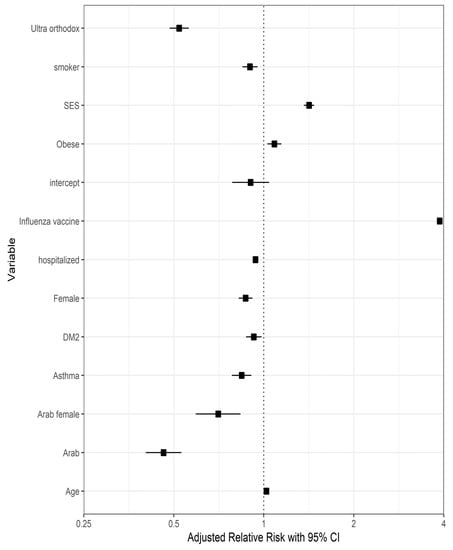

Table 5 presents the results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis of the variables associated with COVID-19 vaccination rates among adults. The model identified five independent variables that were significantly (p < 0.001) associated with low vaccination rates. Among the demographic variables were the minority groups of ultra-Orthodox Jews and the Arab population (odds ratios: 0.484 and 0.453, respectively; p < 0.001 for both). Among the underlying conditions were individuals with asthma, smoking and diabetes mellitus (odds ratios: 0.843, 0.901 and 0.929, respectively; p values: <0.001, <0.001 and 0.011, respectively). In contrast, obesity was significantly and independently associated with an increased vaccine acceptance (odds ratio 1.086, p = 0.003).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of variables associated with COVID-19 vaccination rates.

Gender differences were noted among the minority groups: Arab women were at risk of a low vaccination rate, whereas ultra-Orthodox women showed a relatively high vaccination rate compared to corresponding males (odds ratios 0.728 and 1.136, respectively), although they were still less likely to be vaccinated than the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish population. In the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish population, after adjustment for age, elderly women were significantly less likely to vaccinate than men. Lower SES was negatively associated with getting vaccinated (odds ratio 0.705, p < 0.001). A non-parametric forest plot describing the adjusted relative risks of the various variables on vaccine acceptance is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot describing the adjusted relative risks of various variables on vaccine acceptance.

4. Discussion

In this large observational study, we explored factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Israeli adults to elucidate public health-targeted interventions that are needed to increase vaccine acceptance and reduce the COVID-19-associated morbidity and mortality. We found that Arabs and ultra-Orthodox Jews, which are two Israeli religious minority groups, had substantially lower vaccination rates compared to the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish population.

The Israeli population consists of approximately 74% Jews, 21% Arabs, and 5% of other ethnicities [13]. The Arab population tends to live in crowded neighborhoods [14] and is at a relatively high risk of morbidity and mortality related to COVID-19 due to risk factors such as smoking, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and lack of physical activity [15]. There are several potential impediments to COVID-19 vaccination among the Israeli Arab population, including difficulty in reaching vaccination sites, occasional language barriers, less exposure to the national media, concerns about potential adverse effects (especially on fertility and pregnancy), the perception that vaccination risks outweigh potential benefits, and unique needs and concerns of a culturally defined population group [16]. Focused, targeted public health measures are needed in this population, mostly through their trusted religious and community leaders and within their media, taking into account their special culture.

In the Jewish population, about 12% belong to a distinct subpopulation of the religiously ultra-Orthodox, with a distinct ultra-religious education system, often low SES, high fertility rates and crowded living conditions [17]. The ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Israel is very closed-minded and has, by choice, reduced contact with the non-ultra-Orthodox Jewish population. Their religious leaders, the Rabbis, play a central role in their behavior, including around health issues and vaccine acceptance [18]. They have limited access to general media, and thus are prone to disinformation. Targeted public health interventions in this population are required based on their specific cultural principles, addressing their special concerns (i.e., fertility) and delivered through their Rabbinic and communal leaders, community newspapers, sectoral radio stations and other media [16].

Low SES groups have already been reported as disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic with higher morbidity and mortality rates, rendering high vaccination rates crucial in these groups [19,20,21]. Unfortunately, our study shows that adults with low SES had significantly lower COVID-19 vaccination rates. Our results are similar to those reported by Saban et al., including the number of doses received [22]. Vaccination against COVID-19 in Israel is available free of charge, but reduced accessibility of the low SES population to vaccination sites or to vaccine publicity and knowledge probably plays a role, necessitating public health-concentrated measures.

Our finding of reduced vaccination uptake by individuals with certain underlying comorbidities, which are actually associated with increased COVID-19-related complications and mortality, is very disturbing. In the multivariate analysis, we documented that smoking, asthma, and diabetes mellitus are significantly associated with low COVID-19 vaccination rates. Of note, individuals with obesity and with perceived other underlying medical conditions, such as cardiovascular, respiratory, and immune disorders, had high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rates.

Multiple studies showed that smoking was associated with higher risks of increased burden of COVID-19 symptoms and COVID-related morbidity, including respiratory failure and death [23,24,25,26]. Furthermore, several large-scale meta-analyses have concluded that even a history of smoking is associated with a range of adverse outcomes including severe COVID-19 infection and mortality [27,28,29]. The low vaccine acceptance rates among smoking adults might reflect a tendency of this population not to adhere to medical recommendations and might be explained by the failure to administer the clear message that smoking is a risk factor for a severe course of COVID-19. A special effort is needed to clearly deliver this important knowledge.

Obesity has already been extensively reported as one of the chronic pre-existing conditions in adults who are at higher risk of severe COVID-19 disease, leading to hospitalization, admission to intensive care, and death [30,31,32,33,34]. Luckily, it seems that there is a high awareness among Israeli adults with obesity of the special need for COVID-19 vaccination, a very important factor in decreasing COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality.

The prevalence of asthma among COVID-19 patients varies greatly across countries and regions worldwide [35,36,37]. Several meta-analyses have investigated the association between pre-existing asthma and COVID-19 mortality worldwide [35,36,37], with inconsistent conclusions, possibly due to substantial variation in asthma severity and prevalence among different countries. Sunjaya et al. reported that COVID-19 patients with asthma had a significantly increased risk for mortality in Asia, but not in North America, South America and Europe [38]. Another recent study demonstrated that pre-existing asthma was significantly associated with a reduced risk for COVID-19 mortality in the United States [39]. The inconsistent data might have played a role in the significantly reduced vaccine acceptance among individuals with asthma, but their lower vaccination rate compared with the general population is unfortunate and requires focused attention.

Diabetes mellitus is one of the comorbidities closely related to the risk of morbidity and mortality in patients with COVID-19 [40,41,42]. Many studies showed that the proportion of diabetes is higher in COVID-19 patients with a severe clinical course and that people with diabetes are also more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection than those without diabetes [43,44]. Thus, the low vaccine acceptance rate in this population is very disturbing and is probably related mainly to unawareness of the severe course of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Duan et al. [45] explored COVID-19 vaccination behavior and correlates in 645 diabetic patients from two hospitals in China between June and October 2021. They used multivariable logistic regression to determine predictors related to COVID-19 vaccine uptake. A total of 162 vaccinated and 483 unvaccinated eligible diabetic patients were included. Patients who believed that the COVID-19 syndrome is severe believed that vaccination can significantly reduce the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection thought that vaccination is beneficial to themselves and others, and believed that relatives’ vaccination status has a positive impact on their vaccination behavior and were more likely to be vaccinated; worrying about the adverse health effects of COVID-19 vaccine was negatively correlated with the COVID-19 vaccination rate [45].

Benis et al. investigated COVID-19 vaccination adherence and hesitancy among 1644 US social media users, showing that these individuals have mostly a positive attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination and want to protect their families and their relatives as an act of civic responsibility [46]. Shimoni et al. conducted a cross-sectional survey, which found that seeking information from digital sources and non-health-related governmental agencies and family, friends, and influencers was associated with high vaccine intent [47]. These results strengthen our suggestion that using social media is an important means to increase vaccine uptake, especially when addressing targeted populations. Therefore, a special campaign to deliver information about the severe course of COVID-19 in patients with diabetes mellitus is suggested, for example, in forums and social media platforms directed to these patients.

The main strength of this study is the comprehensive and reliable data that were available on these study populations, including detailed demographics, underlying medical disorders, the medication used, and vaccine acceptance. Our study has several limitations. First, data were analyzed at a single district level and not at the nationwide population and, therefore, might not necessarily be representative of the entire population with potential bias. However, as shown above, the population of the district is diverse, with representation from the various ethnic and SES groups in the country. Second, we did not include in our analyses the fourth COVID-19 vaccine dose; however, this dose was recommended in Israel only for specific high-risk groups, thus vaccine acceptance rates were actually impossible to study. Third, it is always possible that additional variables that we could not study affected vaccine acceptance.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusion of the present study is that, although COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the adult Israeli population is relatively high (>84%), it is significantly lower among certain populations, including in groups at high risk of severe course and complications of COVID-19, such as those with comorbidities. Targeted public health interventions aimed at these populations are required with consideration of their special social characteristics and underlying conditions. Targeted delivery of key messages to the identified populations is currently possible, for example, by community/religious leaders, newsletters, specialized media and social media networks. It is suggested that health policymakers use the aid of experts in online health communication and social networking. Targeted needs of special populations such as those with low SES should also be planned, for example, by making vaccination sites more accessible (mobile vaccination teams, availability after working hours, etc.).

Author Contributions

V.S.Z., Z.G., H.A.C. and S.A. conceived the study idea and designed the study; M.H. performed the statistical analysis; V.S.Z., M.H., M.G., N.Y. and M.C. contributed to the data extraction; V.S.Z., Z.G., H.A.C., M.H. and S.A. interpreted the analysis; V.S.Z., Z.G. and S.A. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for a significant contribution. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Ariel University-Clalit Health Services Research Foundation. Grant No. RA2100000303.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Clalit Health Services (approval number 0087-21-COM1, 28 March 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Participant consent was waived due to a retrospective chart review of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sources of the participants are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

COVID-19—coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; WHO—World Health Organization; CHS—Clalit Health Services; SES—socioeconomic status; DM2–diabetes mellitus type 2; CI—confidence interval.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Joshee, S.; Vatti, N.; Chang, C. Long-term effects of COVID-19. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonelli, M.; Penfold, R.S.; Merino, J.; Sudre, C.H.; Molteni, E.; Berry, S.; Canas, L.S.; Graham, M.S.; Klaser, K.; Modat, M.; et al. Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: A prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfizer Manufacturing Belgium NV. Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine: Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers Administering Vaccine (Vaccination Providers). 2021. Available online: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=16073&format=pdf (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Walsh, E.E.; Frenck, R.W., Jr.; Falsey, A.R.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Neuzil, K.; Mulligan, M.J.; Bailey, R.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based COVID-19 vaccine candidates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2439–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, U.; Muik, A.; Vogler, I.; Derhovanessian, E.; Kranz, L.M.; Vormehr, M.; Quandt, J.; Bidmon, N.; Ulges, A.; Baum, A.; et al. BNT162b2 vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific T cells in humans. Nature 2021, 595, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tregoning, J.S.; Flight, K.E.; Higham, S.L.; Wang, Z.; Pierce, B.F. Progress of the COVID-19 vaccine effort: Viruses, vaccines and variants versus efficacy, effectiveness and escape. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA Takes Key Action in Fight against COVID-19 by Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for First COVID-19 Vaccine. News Release of the Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD. 11 December 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19 (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- World Health Organization. Available online: www.gov.il (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Barda, N.; Dagan, N.; Cohen, C.; Hernán, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Kohane, I.S.; Reis, B.Y.; Balicer, R.D. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: An observational study. Lancet 2021, 398, 2093–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/pages/default.aspx (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Chernichovsky, D.; Bisharat, B.; Bowers, L.; Brill, A.; Sharony, C.; Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. The Health of the Arab Israeli Population. State of the Nation Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.taubcenter.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/healthofthearabisraelipopulation.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel. The Singer Series: State of the Nation Report, 2017. The Health of the Arab Israeli Population.pdf. Available online: https://taubcenter.org.il/state-of-the-nation-report-2017/ (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Rosen, B.; Waitzberg, R.; Israeli, A.; Hartal, M.; Davidovitch, N. Addressing vaccine hesitancy and access barriers to achieve persistent progress in Israel’s COVID-19 vaccination program. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2021, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahaner, L.; Malach, G. The Yearbook of Ultraorthodox Society in Israel, 2019. Online. The Israel Democracy Institute. 2019. Available online: https://en.idi.org.il/media/14526/statistical-report-on-ultra-orthodox-haredi-society-in-israel-2019.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2022).

- Romem, A.; Pinchas-Mizrachi, R.; Zalcman, B.G. Utilizing the ACCESS model to understand communication with the ultraorthodox community in Beit Shemesh during the first wave of COVID-19. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2021, 32, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Disparities in the Risk and Outcomes of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Seligman, B.; Ferranna, M.; Bloom, D.E. Social determinants of mortality from COVID-19: A simulation study using NHANES. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M.; Allen, J.; Goldblatt, P.; Herd, E.; Morrison, J. Build Back Fairer: The COVID-19 Marmot Review. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/Publications/Build-Back-Fairer-the-Covid-19-Marmot-Review (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Saban, M.; Myers, V.; Ben-Shetrit, S.; Wilf-Miron, R. Socioeconomic gradient in COVID-19 vaccination: Evidence from Israel. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, E.J.; Walker, A.J.; Bhaskaran, K.; Bacon, S.; Bates, C.; Morton, C.E.; Curtis, H.J.; Mehrkar, A.; Evans, D.; Inglesby, P.; et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020, 584, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Brown, J.; Shahab, L.; Steptoe, A.; Fancourt, D. COVID-19, smoking and inequalities: A study of 53,002 adults in the UK. Tob. Control 2021, 30, e111–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkinson, N.S.; Rossi, N.; El-Sayed Moustafa, J.; Laverty, A.A.; Quint, J.K.; Freidin, M.; Visconti, A.; Murray, B.; Modat, M.; Ourselin, S.; et al. Current smoking and COVID-19 risk: Results from a population symptom app in over 2.4 million people. Thorax 2021, 76, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsford, M.J.; Gkatzionis, A.; Walker, V.M.; Grant, A.J.; Wootton, R.E.; Moore, L.S.P.; Fatumo, S.; Mason, A.M.; Zuber, V.; Willer, C.; et al. Cardiometabolic traits, sepsis, and severe COVID-19: A Mendelian randomization investigation. Circulation 2020, 142, 1791–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Ruiz, C.A.; López-Padilla, D.; Alonso-Arroyo, A.; Aleixandre-Benavent, R.; Solano-Reina, S.; de Granda-Orive, J.I. COVID-19 and smoking: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2021, 57, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.K.; Charles, W.N.; Sklavounos, A.; Dutt, A.; Seed, P.T.; Khajuria, A. The effect of smoking on COVID-19 severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülsen, A.; Yigitbas, B.A.; Uslu, B.; Drömann, D.; Kilinc, O. The effect of smoking on COVID-19 symptom severity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pulm. Med. 2020, 2020, 7590207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treskova-Schwarzbach, M.; Haas, L.; Reda, S.; Pilic, A.; Borodova, A.; Karimi, K.; Koch, J.; Nygren, T.; Scholz, S.; Schönfeld, V.; et al. Pre-existing health conditions and severe COVID-19 outcomes: An umbrella review approach and meta-analysis of global evidence. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, J.; Tipparaju, P.; Mulherkar, T.; Lin, E.; Mischley, V.; Kulkarni, R.; Bolton, A.; Byrareddy, S.N.; Jain, P. Risk factors associated with the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 and its variants in the context of cytokine storm and therapeutics/vaccine development challenges. Vaccines 2021, 9, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Huang, Y.M.; Wang, M.; Ling, W.; Sui, Y.; Zhao, H.L. Obesity in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism 2020, 113, 154378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamara, A.; Tahapary, D.L. Obesity as a predictor for a poor prognosis of COVID-19: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonnet, A.; Chetboun, M.; Poissy, J.; Raverdy, V.; Noulette, J.; Duhamel, A.; Labreuche, J.; Mathieu, D.; Pattou, F.; Jourdain, M.; et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity 2020, 28, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Cao, Y.; Du, T.; Zhi, Y. Prevalence of comorbid asthma and related outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Xu, J.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Chen, S.; Duan, G.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. Asthma in patients with coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, P.D.; Heidel, R.E.; Dhand, R. Asthma in adult patients with COVID-19. Prevalence and risk of severe disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunjaya, A.P.; Allida, S.M.; Di Tanna, G.L.; Jenkins, C.R. Asthma and COVID-19 risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Xu, J.; Hou, H.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. Impact of asthma on COVID-19 mortality in the United States: Evidence based on a meta-analysis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 102, 108390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J.M.; Slaughter, J.C.; Duffus, S.H.; Smith, T.J.; LeStourgeon, L.M.; Jaser, S.S.; McCoy, A.B.; Luther, J.M.; Giovannetti, E.R.; Boeder, S.; et al. COVID-19 severity is tripled in the diabetes community: A prospective analysis of the pandemic’s impact in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.; Lim, M.A.; Pranata, R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itelman, E.; Wasserstrum, Y.; Segev, A.; Avaky, C.; Negru, L.; Cohen, D.; Turpashvili, N.; Anani, S.; Zilber, E.; Lasman, N.; et al. Clinical Characterization of 162 COVID-19 patients in Israel: Preliminary report from a large tertiary center. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 22, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barron, E.; Bakhai, C.; Kar, P.; Weaver, A.; Bradley, D.; Ismail, H.; Knighton, P.; Holman, N.; Khunti, K.; Sattar, N.; et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England: A whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariou, B.; Hadjadj, S.; Wargny, M.; Pichelin, M.; Al-Salameh, A.; Allix, I.; Amadou, C.; Arnault, G.; Baudoux, F.; Bauduceau, B.; et al. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID-19 and diabetes: The CORONADO study. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 1500–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Song, C.; Zheng, J.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, J. The COVID-19 vaccination behavior and correlates in diabetic patients: A health belief model theory-based cross-sectional study in China, 2021. Vaccines 2022, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benis, A.; Seidmann, A.; Ashkenazi, S. Reasons for Taking the COVID-19 Vaccine by US Social Media Users. Vaccines 2021, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Gui, H.; Chua, P.E.Y.; Tan, J.B.; Suen, L.K.; Chan, S.W.; Pang, J. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intent in Singapore, Australia and Hong Kong. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2949–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).