Effectiveness of Exercise Interventions for Improving Dual-Task Gait Speed in People with Stroke Sequelae: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Formulation of the Research Question and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: adults with post-stroke sequelae;

- Intervention: any exercise-based intervention;

- Comparison: any other exercise-based intervention;

- Outcome: gait speed under dual-task conditions (primary outcome, mandatory) and dual-task cost/effect (secondary outcome, if reported);

- Publication: full-text articles in English or Portuguese, published from January 2017 onward.

- Neurological conditions other than stroke;

- Dual-task assessment restricted to static balance;

- Animal studies;

- Retracted or withdrawn publications.

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.6. Data Synthesis

2.7. Presentation of Results

2.8. Narrative Synthesis

- Direction of effect: identifying which intervention was associated with superior outcomes;

- Magnitude of effect: evaluating the size of observed differences.

2.9. Sensitivity Analysis

2.10. Risk of Bias and Methodological Quality Assessment

3. Results

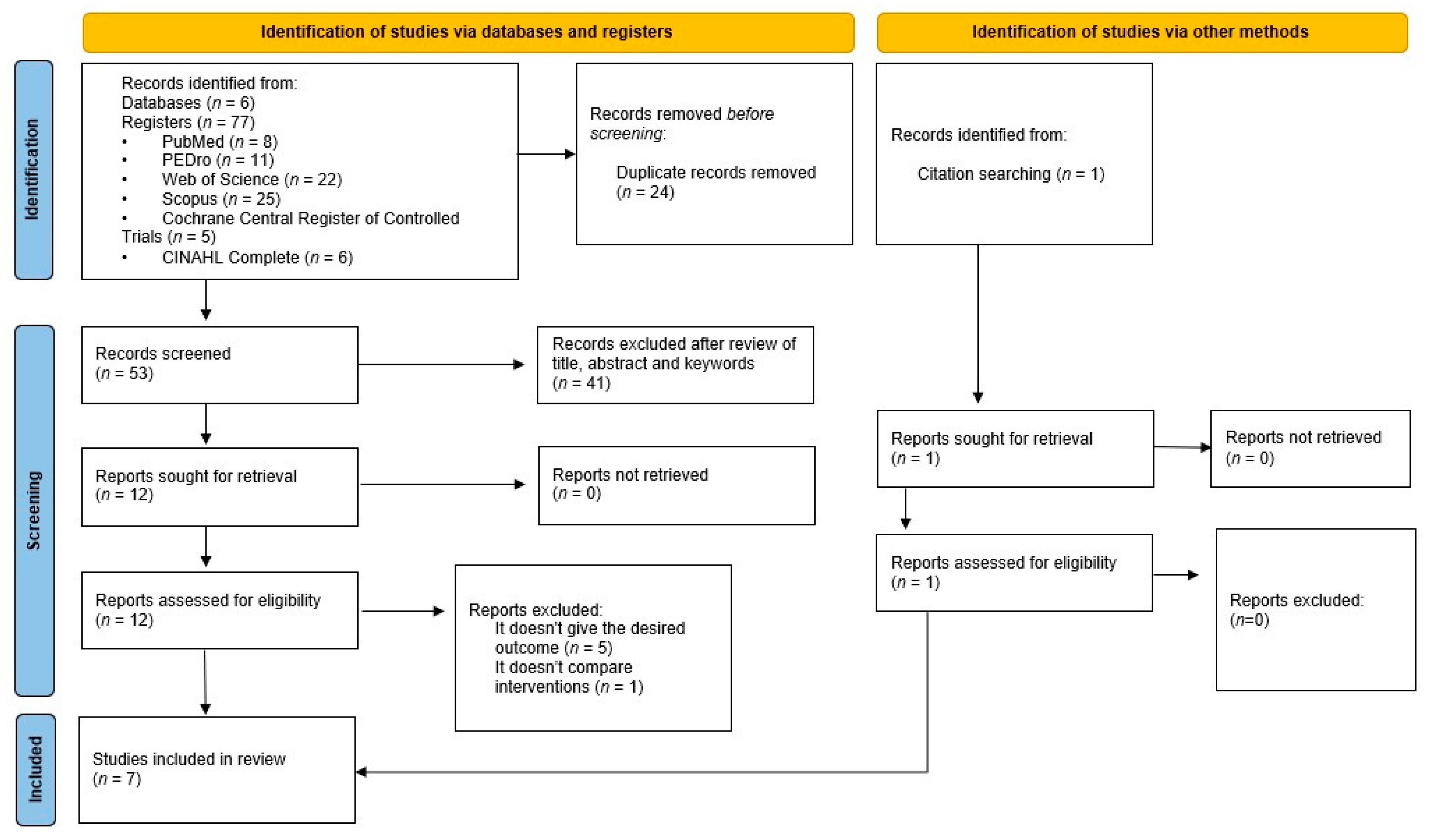

3.1. Study Selection Process

3.2. Methodological Quality of Studies

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. Study Analysis

3.4.1. Within-Group Analyses

3.4.2. Between-Group Comparisons

3.4.3. Follow-Up Assessments

3.4.4. Influence of Methodological Quality

3.5. Narrative Analysis of the Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BA | Blinding of Assessors |

| BS | Blinding of Subjects |

| BT | Blinding of Therapists |

| CA | Concealed Allocation |

| ECS | Eligibility Criteria Specified |

| GSB | Group Similar at Baseline |

| ITA | Intention-to-Treat Analysis |

| NR | Not Reported |

| OD | Outcome Data from >85% of Subjects |

| PEVM | Point Estimates and Variability Measures |

| RA | Random Allocation |

| RBC | Reported Between-group Comparisons |

Appendix A. Full Search Strategy Used in Web of Science

| ( |

| TS = (stroke OR cerebrovascular accident OR cerebral stroke OR cerebrovascular apoplexy OR brain vascular accident OR cerebrovascular stroke OR apoplexy OR CVA OR CVAs OR cerebrovascular accidents OR brain vascular accidents OR cerebral strokes) |

| AND |

| TS = (exercise therapy OR rehabilitation exercise OR exercise, rehabilitation OR exercises rehabilitation OR rehabilitation exercises OR therapy, exercise OR exercise therapies OR therapies, exercise) |

| AND |

| TS = (walking speed OR speeds, walking OR speed, walking OR walking speeds OR walking pace OR paces, walking OR pace, walking OR walking paces OR gait speed OR gait speeds OR speed gait OR speeds, gait) |

| AND |

| TS = (dual task* OR dual-task*) |

| ) |

References

- Feld, J.A.; Zukowski, L.A.; Howard, A.G.; Giuliani, C.A.; Altmann, L.J.P.; Najafi, B.; Plummer, P. Relationship Between Dual-Task Gait Speed and Walking Activity Poststroke. Stroke 2018, 49, 1296–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, C.; Jiang, Y. Effect of dual task-based training on motor and cognitive function in stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trails. BMC Neurol. 2025, 25, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Magdaleno, M.; Pereiro, A.; Navarro-Pardo, E.; Juncos-Rabadán, O.; Facal, D. Dual-task performance in old adults: Cognitive, functional, psychosocial and socio-demographic variables. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2022, 34, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Barros, G.M.; Melo, F.; Domingos, J.; Oliveira, R.; Silva, L.; Fernandes, J.B.; Godinho, C. The Effects of Different Types of Dual Tasking on Balance in Healthy Older Adults. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblock-Bellamy, A.; Lamontagne, A.; Blanchette, A.K. Cognitive-Locomotor Dual-Task Interference in Stroke Survivors and the Influence of the Tasks: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deblock-Bellamy, A.; Lamontagne, A.; McFadyen, B.J.; Ouellet, M.C.; Blanchette, A.K. Dual-Task Abilities During Activities Representative of Daily Life in Community-Dwelling Stroke Survivors: A Pilot Study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 855226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Iyigün, G. Effects of Physical Exercise Interventions on Dual-Task Gait Speed Following Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018, 99, 2548–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, F.; Shi, H.; Liu, R.; Wan, X. Effects of dual-task training on gait and balance in stroke patients: A meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2022, 36, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Whitton, N.; Zand, R.; Dombovy, M.; Parnianpour, M.; Khalaf, K.; Rashedi, E. A Systematic Review of Fall Risk Factors in Stroke Survivors: Towards Improved Assessment Platforms and Protocols. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 910698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, D.; Joshua, A.M.; K, V.K.; Nayak, A.; Mithra, P.; Pai, R.; Pai, S.; Krishnan K, S.; Palaniswamy, V. Dual tasking as a predictor of falls in post-stroke: A cross-sectional analysis comparing Walking While Talking versus Stops Walking While Talking. F1000Res 2024, 13, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurovic, O.; Mihaljevic, O.; Radovanovic, S.; Kostic, S.; Vukicevic, M.; Brkic, B.G.; Stankovic, S.; Radulovic, D.; Vukomanovic, I.S.; Radevic, S.R. Risk Factors Related to Falling in Patients after Stroke. Iran. J. Public. Health 2021, 50, 1832–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Lee, G. Impaired dynamic balance is associated with falling in post-stroke patients. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2013, 230, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Yu, J.; Rhee, H. Risk factors related to falling in stroke patients: A cross-sectional study. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1751–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, C.U.; Hansson, P.O. Determinants of falls after stroke based on data on 5065 patients from the Swedish Väststroke and Riksstroke Registers. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayabinar, B.; Alemdaroğlu-Gürbüz, İ.; Yilmaz, Ö. The effects of virtual reality augmented robot-assisted gait training on dual-task performance and functional measures in chronic stroke: A randomized controlled single-blind trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaramonte, R.; Bonfiglio, M.; Leonforte, P.; Coltraro, G.L.; Guerrera, C.S.; Vecchio, M. Proprioceptive and Dual-Task Training: The Key of Stroke Rehabilitation, A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, N.E.; Cheek, F.M.; Nichols-Larsen, D.S. Motor-Cognitive Dual-Task Training in Persons With Neurologic Disorders: A Systematic Review. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2015, 39, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wan, X. Comparative effects of arithmetic, speech, and motor dual-task walking on gait in stroke survivors: A cross-sectional study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1587153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alingh, J.F.; Groen, B.E.; Kamphuis, J.F.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Weerdesteyn, V. Task-specific training for improving propulsion symmetry and gait speed in people in the chronic phase after stroke: A proof-of-concept study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Pellicer, M.; Chamarro-Lusar, A.; Medina-Casanovas, J.; Serdà Ferrer, B.C. Walking speed as a predictor of community mobility and quality of life after stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2019, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.; Xiao, W. Comparing the effectiveness of dual-task and single-task training on walking function in stroke recovery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2025, 104, e41776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Eskes, G. Measuring treatment effects on dual-task performance: A framework for research and clinical practice. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, M.; Kuber, P.M.; Rashedi, E. Dual Tasking Affects the Outcomes of Instrumented Timed up and Go, Sit-to-Stand, Balance, and 10-Meter Walk Tests in Stroke Survivors. Sensors 2024, 24, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Quan, W.; Jiang, X.; Liang, M.; Li, S.; Ugbolue, U.C.; Baker, J.S.; Gusztav, F.; Ma, X.; et al. A new method proposed for realizing human gait pattern recognition: Inspirations for the application of sports and clinical gait analysis. Gait Posture 2024, 107, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, M.; Chiaramonte, R.; De Sire, A.; Buccheri, E.; Finocchiaro, P.; Scaturro, D.; Letizia Mauro, G.; Cioni, M. Do proprioceptive training strategies with dual-task exercises positively influence gait parameters in chronic stroke? A systematic review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, jrm18396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Bi, M.M.; Zhou, T.T.; Liu, L.; Zhang, C. Effect of Dual-Task Training on Gait and Balance in Stroke Patients: An Updated Meta-analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 1148–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.S.M.; Rehab, N.I.; Aly, S.M.A. Effect of aquatic versus land motor dual task training on balance and gait of patients with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2019, 44, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landim, S.F.; López, R.; Caris, A.; Castro, C.; Castillo, R.D.; Avello, D.; Magnani Branco, B.H.; Valdés-Badilla, P.; Carmine, F.; Sandoval, C.; et al. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality in Occupational Therapy for Post-Stroke Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.-Q.; Wei, M.-F.; Chen, L.; Xi, J.-N. Research progress in the application of motor-cognitive dual-task training in rehabilitation of walking function in stroke patients. J. Neurorestoratology 2023, 11, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Tabassum, D.; Baig, S.S.; Moyle, B.; Redgrave, J.; Nichols, S.; McGregor, G.; Evans, K.; Totton, N.; Cooper, C.; et al. Effect of Exercise Interventions on Health-Related Quality of Life After Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stroke 2021, 52, 2445–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, D.; Goldberg, C.; Winterbottom, L.; Nilsen, D.M.; Mahoney, D.; Gillen, G. Task Oriented Training Interventions for Adults With Stroke to Improve ADL and Functional Mobility Performance (2012–2019). Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 77, 7710393050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, K.S.; Moncion, K.; Wiley, E.; Morgan, A.; Huynh, E.; Balbim, G.M.; Elliott, B.; Harris-Blake, C.; Krysa, B.; Koetsier, B.; et al. Prescribing strength training for stroke recovery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2025, 59, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, R.; Triolo, G.; Ivaldi, D.; Quartarone, A.; Lo Buono, V. The Role of Dance in Stroke Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review of Functional and Cognitive Effects. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tally, Z.; Boetefuer, L.; Kauk, C.; Perez, G.; Schrand, L.; Hoder, J. The efficacy of treadmill training on balance dysfunction in individuals with chronic stroke: A systematic review. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2017, 24, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, L.C.; Hsu, A.L.; Hu, G.C.; Ou, Y.C.; Chen, A.C.; Chuang, L.L. Cognitive and motor multi-task balance training improves dual-task walking performance in ambulatory patients after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, B.; Thomas, L.H.; Coupe, J.; McMahon, N.E.; Connell, L.; Harrison, J.; Sutton, C.J.; Tishkovskaya, S.; Watkins, C.L. Repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 11, CD006073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, B.; Koohi, N.; Kaski, D.; Bamiou, D.E.; Pavlou, M. Impact of Vestibular Rehabilitation and Dual-Task Training on Balance and Gait in Survivors of Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e040663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, J.; Truijen, S.; Van Criekinge, T.; Saeys, W. Feasibility and effectiveness of repetitive gait training early after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 51, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwakkel, G.; Stinear, C.; Essers, B.; Munoz-Novoa, M.; Branscheidt, M.; Cabanas-Valdés, R.; Lakičević, S.; Lampropoulou, S.; Luft, A.R.; Marque, P.; et al. Motor rehabilitation after stroke: European Stroke Organisation (ESO) consensus-based definition and guiding framework. Eur. Stroke J. 2023, 8, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, B.A.; Bonuzzi, G.M.G.; Alves, C.M.P.; Polese, J.C.; Mochizuki, L.; Torriani-Pasin, C. Does dual task merged in a mixed physical exercise protocol impact the mobility under dual task conditions in mild impaired stroke survivors? A feasibility, safety, randomized, and controlled pilot trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, C.Y.; Chang, W.N.; Park, B.Y.; Lee, K.B.; Kang, K.Y.; Choi, M.R. Effects of Dual-Task Gait Treadmill Training on Gait Ability, Dual-Task Interference, and Fall Efficacy in People With Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, L.L.; Hsu, A.L.; Lin, Y.H.; Yu, M.H.; Hu, G.C.; Ou, Y.C.; Wong, A.M. Multimodal training with dual-task enhances immediate and retained effects on dual-task effects of gait speed not by cognitive-motor trade-offs in stroke survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2025, 47, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.C.; Yang, Y.R.; Tsai, Y.A.; Wang, R.Y. Cognitive and motor dual task gait training improve dual task gait performance after stroke—A randomized controlled pilot trial. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, D.; Al-Yahya, E.; Dennis, A.; Collett, J.; Wade, D.T.; Ovington, M.; Liu, F.; Meaney, A.; Cockburn, J.; Johansen-Berg, H.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of a walking training with simultaneous cognitive demand (dual-task) in chronic stroke. Eur. J. Neurol. 2019, 26, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, P.; Zukowski, L.A.; Feld, J.A.; Najafi, B. Cognitive-motor dual-task gait training within 3 years after stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2022, 38, 1329–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, C.; Roerdink, M.; Meskers, C.G.M.; Beek, P.J.; Janssen, T.W.J. Walking-adaptability therapy after stroke: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platz, T. Evidence-Based Guidelines and Clinical Pathways in Stroke Rehabilitation-An International Perspective. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhunter-Brown, A.; Sellers, C.E.; Baer, G.D.; Choo, P.L.; Cowie, J.; Cheyne, J.D.; Langhorne, P.; Brown, J.; Morris, J.; Campbell, P. Physical rehabilitation approaches for the recovery of function and mobility following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2, CD001920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, J.; Kashif, A.; Shahid, M.K. A Comprehensive Review of Physical Therapy Interventions for Stroke Rehabilitation: Impairment-Based Approaches and Functional Goals. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yao, L. Mediation and moderation analysis of the association between physical capability and quality of life among stroke patients. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.S.; Wang, S.; Miller, T.; Pang, M.Y. Degree and pattern of dual-task interference during walking vary with component tasks in people after stroke: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2022, 68, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, R.B. PEDro: A physiotherapy evidence database. Med. Ref. Serv. Q. 2008, 27, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, R.; Moseley, A.; Sherrington, C. PEDro: A database of randomised controlled trials in physiotherapy. Health Inf. Manag. 1998, 28, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.G.; Moseley, A.M.; Sherrington, C.; Elkins, M.R.; Herbert, R.D. A description of the trials, reviews, and practice guidelines indexed in the PEDro database. Phys. Ther. 2008, 88, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M.R.; Van der Wees, P.J.; Pinheiro, M.B. Using research to guide practice: The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2020, 24, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Maher, C.G.; Moseley, A.M. PEDro. A database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiotherapy. Man. Ther. 2000, 5, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrington, C.; Moseley, A.M.; Herbert, R.D.; Elkins, M.R.; Maher, C.G. Ten years of evidence to guide physiotherapy interventions: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 836–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, S.; Lusardi, M. White paper: “walking speed: The sixth vital sign”. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2009, 32, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, A.; Fritz, S.L.; Lusardi, M. Walking speed: The functional vital sign. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasseel-Ponche, S.; Roussel, M.; Toba, M.N.; Sader, T.; Barbier, V.; Delafontaine, A.; Meynier, J.; Picard, C.; Constans, J.M.; Schnitzler, A.; et al. Dual-task versus single-task gait rehabilitation after stroke: The protocol of the cognitive-motor synergy multicenter, randomized, controlled superiority trial (SYNCOMOT). Trials 2023, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilson, J.K.; Sullivan, K.J.; Cen, S.Y.; Rose, D.K.; Koradia, C.H.; Azen, S.P.; Duncan, P.W. Meaningful gait speed improvement during the first 60 days poststroke: Minimal clinically important difference. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristina da Silva, L.; Danielli Coelho de Moraes Faria, C.; da Cruz Peniche, P.; Ayessa Ferreira de Brito, S.; Tavares Aguiar, L. Validity of the two-minute walk test to assess exercise capacity and estimate cardiorespiratory fitness in individuals after stroke: A cross-sectional study. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2024, 31, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.H.; Woo, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.H. Effects of task-oriented treadmill-walking training on walking ability of stoke patients. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2015, 22, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; He, C.; Pang, M.Y. Reliability and Validity of Dual-Task Mobility Assessments in People with Chronic Stroke. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.Y.; Han, M.R.; Lee, H.G. Effect of Dual-task Rehabilitative Training on Cognitive and Motor Function of Stroke Patients. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2014, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarello, F.; Bianchi, V.A.; Baccini, M.; Rubbieri, G.; Mossello, E.; Cavallini, M.C.; Marchionni, N.; Di Bari, M. Tools for observational gait analysis in patients with stroke: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 1673–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.H.; Hsu, M.J.; Hsu, H.W.; Wu, H.C.; Hsieh, C.L. Psychometric comparisons of 3 functional ambulation measures for patients with stroke. Stroke 2010, 41, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, M.; Rashedi, E.; Kuber, P.M.; Jahangiri, S.; Kazempour, B.; Dombovy, M.; Azadeh-Fard, N. Post-Stroke Functional Changes: In-Depth Analysis of Clinical Tests and Motor-Cognitive Dual-Tasking Using Wearable Sensors. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. i–xxviii. 694p. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.; Katikireddi, S.; Sowden, A.; McKenzie, J.; Thomson, H. Improving Conduct and Reporting of Narrative Synthesis of Quantitative Data (ICONS-Quant): Protocol for a mixed methods study to develop a reporting guideline. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiwa, S.R.; Costa, L.O.; Costa, L.a.C.; Moseley, A.; Hespanhol Junior, L.C.; Venâncio, R.; Ruggero, C.; Sato, T.e.O.; Lopes, A.D. Reproducibility of the Portuguese version of the PEDro Scale. Cad. Saude Publica 2011, 27, 2063–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morton, N.A. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: A demographic study. Aust. J. Physiother. 2009, 55, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, M.R.; Moseley, A.M.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Maher, C.G. Growth in the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) and use of the PEDro scale. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.P.; Pegorari, M.S. How to Classify Clinical Trials Using the PEDro Scale? J. Lasers Med. Sci. 2020, 11, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, A.M.; Herbert, R.; Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Elkins, M.R. PEDro scale can only rate what papers report. Aust. J. Physiother. 2008, 54, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutron, I.; Guittet, L.; Estellat, C.; Moher, D.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Ravaud, P. Reporting methods of blinding in randomized trials assessing nonpharmacological treatments. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Garrett, M.; Gronley, J.K.; Mulroy, S.J. Classification of walking handicap in the stroke population. Stroke 1995, 26, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Individual Item Ratings and Total PEDro Scores | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | #1 ECS | #2 RA | #3 CA | #4 GSB | #5 BS | #6 BT | #7 BA | #8 OD | #9 ITA | #10 RBC | #11 PEVM | Total |

| Antonio et al. 2022 (Brazil) [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/10 |

| Baek et al. 2021 (Republic of Korea) [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7/10 |

| Chuang et al. 2025 (Taiwan) [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7/10 |

| Liu et al. 2017 (Taiwan) [43] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | 5/10 |

| Meester et al. 2019 (UK) [44] | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6/10 |

| Plummer et al. 2021 (USA) [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8/10 |

| Timmermans et al. 2021 (The Netherlands) [46] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6/10 |

| Study | Intervention | Control | Sample Size | Gender (M/F) | Stroke Type (Ischemic/ Hemorrhagic) | Measures of Dual-Task Gait Speed † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio et al. 2022 (Brazil) [40] | Mixed Physical Exercise with Dual-Task | Mixed Physical Exercise (Single-Task) | 26 | 13/13 | NR | 10 m walk test with verbal fluency task (s); comfortable walking speed |

| Baek et al. 2021 (Republic of Korea) [41] | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task and Simple Exercise | Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task), Cognitive Training and Simple Exercise | 31 | 20/11 | 11/20 | 4 m walk with serial-three subtraction task (2-digit) analysed with OptoGait (m/s); walking speed type not specified |

| Chuang et al. 2025 (Taiwan) [42] | Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 44 | 26/18 | 17/27 | 10 m walk with Stroop task, timed with stopwatch (m/s); self-paced walking speed |

| 10 m walk with serial-three subtraction task, timed with stopwatch (m/s); self-paced walking speed | ||||||

| Liu et al. 2017 (Taiwan) [43] | Overground Gait Training with Cognitive Dual-Task | Conventional Physical Therapy | 28 | 24/4 | 16/12 | 4.3 m walk with serial-three subtraction task (3-digit) analysed with GAITRite (cm/s); comfortable walking speed |

| Overground Gait Training with Motor Dual-Task | ||||||

| Meester et al. 2019 (UK) [44] | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task | Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task) | 50 | 26/24 | 31/17 * | Two-minute walk test with daily life questions (m); self-selected walking speed |

| Plummer et al. 2021 (USA) [45] | Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 36 | 19/17 | 28/8 | 10 m walk with Stroop task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system (m/s); fast walking speed |

| 10 m walk with Stroop task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system (m/s); preferred walking speed | ||||||

| 10 m walk with Clock task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; (m/s); fast walking speed | ||||||

| 10 m walk with Clock task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; (m/s); preferred walking speed | ||||||

| Timmermans et al. 2021 (The Netherlands) [46] | Treadmill-Based C-Mill Therapy | Standard Overground FALLS Program | 33 | 19/14 | NR | 10 m walk with serial-three subtraction task (m/s); self-selected walking speed |

| Study | Duration (Weeks, Sessions, Session Duration) | Group/Intervention | Detailed Description of Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio et al. 2022 (Brazil) [40] | 15 weeks (30 sessions of 60–90 min) | Mixed Physical Exercise with Dual-Task | Aerobic exercise training was performed on a treadmill (Polimect-Advanced 20) with simultaneous cognitive tasks, including calculation, identification and working memory, tracking, and decision-making. The resistance exercise protocol included free-weight squats, horizontal leg-press, unilateral pull-down machine, unilateral chest-press, and free-weight plantar-flexion, combined with cognitive tasks targeting working memory, verbal fluency, and information manipulation and categorization. Each session lasted 60–90 min. |

| Mixed Physical Exercise (Single-Task) | The control group followed the same physical exercise protocol without any cognitive tasks. | ||

| Baek et al. 2021 (Republic of Korea) [41] | 6 weeks (12 sessions of 60 min) | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task and Simple Exercise | 30 min of treadmill walking combined with cognitive tasks (mental tracking, verbal fluency, and executive function/Stroop task) followed by 30 min of simple exercises in the supine and sitting positions. |

| Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task), Cognitive Training and Simple Exercise | 30 min of treadmill walking without cognitive tasks, followed by 30 min of simple exercises in the supine and sitting positions combined with cognitive tasks similar to those of the experimental group, but exclusively performed in supine or sitting positions to avoid dual-tasking while standing. | ||

| Chuang et al. 2025 (Taiwan) [42] | 4 weeks (12 sessions of 60 min) | Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | Same multimodal physical structure as the single-task program, but combined with concurrent cognitive tasks (visual discrimination, verbal fluency, and calculation tasks). |

| Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 5 min warm-up + 20 min standing balance training using the Biodex BioSway™ Portable Balance System (Biodex Medical Systems, Inc., Shirley, NY, USA) (including weight-bearing, postural stability, weight shifting, limits of stability, and random control training) + 10 min sit-to-stand training (progressively increasing paretic limb loading and weight-bearing symmetry) + 20-min treadmill walking with weekly target speeds + 5-min cool-down. | ||

| Liu et al. 2017 (Taiwan) [43] | 4 weeks (12 sessions of 30 min) | Overground Gait Training with Cognitive Dual-Task | During walking conditions—walking forward, walking backward, and walking on an S-shaped route—the participants were instructed to perform cognitive tasks: (1) walking while repeating phrases; (2) walking while counting numbers forward in order by ones; (3) walking while counting numbers backward in order by ones; (4) walking while executing a word chain (i.e., speaking out a word that begins with the last letter of the previous word); (5) walking while reciting a poem; (6) walking while talking; and (7) walking while reciting a sentence backward. |

| Overground Gait Training with Motor Dual-Task | During walking conditions—walking forward, walking backward, and walking on an S-shaped route—the participants were instructed to perform motor tasks: (1) walking while holding one or two balls; (2) walking while raising an umbrella using both hands; (3) walking while waving a rattle; (4) walking while beating a castanet; (5) walking while bouncing a basketball; (6) walking while kicking a basketball; and (7) walking while holding one ball and concurrently kicking another basketball into a net. | ||

| Conventional Physical Therapy | Conventional Physiotherapy: muscle strengthening (hip flexors, hip extensors, hip abductors, knee extensors, knee flexors, ankle dorsiflexors, and ankle plantarflexors), balance (weight-shifting exercises in different directions while standing, squatting against a gymnastic ball, standing on a foam with eyes open/closed, tandem standing with eyes open/closed, and single-leg standing), and gait training (walking forward, walking backward, and walking on an S-shaped route). | ||

| Meester et al. 2019 (UK) [44] | 10 weeks (20 sessions of 45 min) | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task | 10 min of warm-up, 30 min of treadmill walking at aerobic intensity (55–85% of maximum heart rate) with three types of simultaneous cognitive distractions: cognitive tasks (two 5 min blocks including subtasks such as Auditory Stroop, Serial Subtraction, Letter Fluency, Alternative Uses, and Creativity), listening to and discussing an audio fragment (10 min), and planning daily activities (two 5-min blocks). Followed by 5 min of cool-down. |

| Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task) | 10 min of warm-up, 30 min of treadmill walking at the same aerobic intensity without cognitive distractions, followed by 5 min of cool-down. | ||

| Plummer et al. 2021 (USA) [45] | 4 weeks (12 sessions of 30 min) | Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | Each session included warm-up, part-task practice, whole-task practice, and contextual training in real environments, following the Motor Relearning Program model. For each activity, participants performed 12 repetitions: the first three as single-task and the subsequent nine as dual-task (75% of repetitions). Nine cognitive tasks were used in a standardized sequence across sessions, with a variable-priority strategy in which participants alternated focus between gait and cognitive task. |

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | Participants underwent the same training structure and paradigm as the DTGT group. The main difference was that no simultaneous cognitive tasks were performed. Participants were instructed to refrain from talking during practice of gait and balance activities. | ||

| Timmermans et al. 2021 (The Netherlands) [46] | 5 weeks (10 sessions of 90 min) | Treadmill-Based C-Mill Therapy | Treadmill training focusing on walking adaptability, using a gait-dependent, projector-generated visual context to elicit step adjustments. The intervention included various exercises designed to practice avoidance of projected visual obstacles, goal-directed foot placement on regular or irregular visual stepping targets (with or without obstacles), gait acceleration and deceleration while maintaining position within a projected walking area that moves along the treadmill, tandem walking, and an interactive walking-adaptability game (90 min, with participants training in pairs). |

| Standard Overground FALLS Program | Obstacle course training consisting of exercises to practice obstacle avoidance, foot placement while walking over uneven terrain, tandem walking, and slalom walking, combined with practice of falling techniques and simulation of walking in a crowded environment (90 min, with participants training in groups of 4–6). |

| Study | Intervention Duration | Group | N | Pre-Intervention Mean ± SD † | Post-Intervention Mean ± SD † | Mean Difference (Within-Group) † | 95% CI of Within-Group Mean Difference † | Mean Difference (Between-Groups) † | 95% CI of Between-Groups Mean Difference † | Measures of Dual-Task Gait Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio et al. 2022 (Brazil) [40] | 15 weeks | Mixed Physical Exercise with Dual-Task | 13 | 0.76 ± 0.33 | 1.07 ± 0.43 | 0.31 * | NR | −0.2 ‡ | [−0.51, 0.11] ‡ | 10 m walk test with verbal fluency task; comfortable walking speed |

| Mixed Physical Exercise (Single-Task) | 13 | 1.01 ± 0.35 | 1.27 ± 0.33 | 0.26 | NR | |||||

| Baek et al. 2021 (Republic of Korea) [41] | 6 weeks | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task and Simple Exercise | 16 | 0.35 ± 0.13 | 0.44 ± 0.13 | 0.09 * | [0.06, 0.12] | 0.04 * | [0.01, 0.08] | 4 m walk with serial-three sub-traction task (2-digit) analysed with OptoGait; walking speed type not specified |

| Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task), Cognitive Training and Simple Exercise | 15 | 0.34 ± 0.18 | 0.39 ± 0.18 | 0.05 * | [0.02, 0.07] | |||||

| Chuang et al. 2025 (Taiwan) [42] | 4 weeks | Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | 22 | 0.88 ± 0.15 | 0.98 ± 0.18 | 0.10 * | NR | 0.09 ‡ | [−0.036, 0.22] ‡ | 10 m walk with Stroop task, timed with stopwatch; self-paced walking speed |

| Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 22 | 0.83 ± 0.22 | 0.89 ± 0.23 | 0.06 * | NR | |||||

| Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | 22 | 0.89 ± 0.16 | 0.94 ± 0.18 | 0.05 * | NR | 0.07 ‡ | [−0.052, 0.19] ‡ | 10 m walk with serial-three subtraction task, timed with stopwatch; self-paced walking speed | ||

| Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 22 | 0.82 ± 0.20 | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.05 * | NR | |||||

| Liu et al. 2017 (Taiwan) [43] | 4 weeks | Overground Gait Training with Cognitive Dual-Task | 9 | 0.564 ± 0.180 | 0.634 ± 0.206 | 0.069 | NR | −0.004 ‡§ | [−0.19, 0.18] ‡§ | 4.3 m walk with serial-three subtraction task (3-digit) analysed with GAITRite; comfortable walking speed |

| Overground Gait Training with Motor Dual-Task | 9 | 0.624 ± 0.138 | 0.638 ± 0.137 | 0.014 | NR | 0.033 ‡¶ | [−0.17, 0.24] ‡¶ | |||

| Conventional Physical Therapy | 10 | 0.621 ± 0.199 | 0.601 ± 0.207 | −0.02 | NR | 0.037 ‡# | [−0.13, 0.21] ‡# | |||

| Meester et al. 2019 (UK) [44] | 10 weeks | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task | 24 | 0.654 ± 0.287 | 0.702 ± 0.287 | 0.048 * | NR | 0.038 ‡ | [−0.11, 0.19] ‡ | Two-minute walk test with daily life questions; self-selected walking speed |

| Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task) | 21 | 0.629 ± 0.280 | 0.664 ± 0.281 | 0.035 * | NR | |||||

| Plummer et al. 2021 (USA) [45] | 4 weeks | Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | 0.95 ± 0.27 | 1.00 ± 0.28 | 0.05 * | [0.004, 0.09] | −0.03 | [−0.09, 0.03] | 10 m walk with Stroop task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; fast walking speed |

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | 0.87 ± 0.33 | 0.95 ± 0.32 | 0.08 * | [0.04, 0.12] | |||||

| Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | 0.85 ± 0.24 | 0.88 ± 0.22 | 0.04 | [−0.03, 0.10] | −0.05 | [−0.12, 0.03] | 10 m walk with Stroop task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; preferred walking speed | ||

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | 0.78 ± 0.27 | 0.88 ± 0.28 | 0.09 * | [0.03, 0.15] | |||||

| Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | 0.90 ± 0.28 | 0.94 ± 0.29 | 0.04 | [−0.02, 0.09] | −0.04 | [−0.12, 0.04] | 10 m walk with Clock task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; fast walking speed | ||

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | 0.87 ± 0.36 | 0.95 ± 0.40 | 0.08 * | [0.03, 0.14] | |||||

| Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | 0.80 ± 0.22 | 0.83 ± 0.25 | 0.03 | [−0.03, 0.09] | −0.03 | [−0.12, 0.05] | 10 m walk with Clock task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; preferred walking speed | ||

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | 0.79 ± 0.29 | 0.86 ± 0.31 | 0.07 * | [0.01, 0.13] | |||||

| Timmermans et al. 2021 (The Netherlands) [46] | 5 weeks | Treadmill-Based C-Mill Therapy | 14 | 0.67 ± 0.25 | 0.76 ± 0.29 | 0.09 ** | NR | −0.04 ‡ | [−0.25, 0.17] ‡ | 10 m walk with serial-three subtraction task; self-selected walking speed |

| Standard Overground FALLS Program | 16 | 0.79 ± 0.25 | 0.80 ± 0.26 | 0.01 ** | NR |

| Study | Group | N | Pre-Intervention Mean ± SD † | Post-Intervention Mean ± SD † | Mean Difference (Within-Group) † | 95% CI of Within-Group Mean Difference † | Mean Difference (Between-Groups) † | 95% CI of Between-Groups Mean Difference † | Type | Formula | Measures of Dual-Task Gait Speed ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio et al. 2022 (Brazil) [40] | Mixed Physical Exercise with Dual-Task | 13 | 47.67 ± 91.53 | 13.88 ± 47.40 | −33.79 * | NR | 1.49 § | [−27.4, 30.38] § | DTC | DTC (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk test with verbal fluency task (s); comfortable walking speed |

| Mixed Physical Exercise (Single-Task) | 13 | 19.67 ± 19.0 | 12.39 ± 8.28 | −7.28 | NR | ||||||

| Baek et al. 2021 (Republic of Korea) [41] | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task and Simple Exercise | 16 | 21.85 ± 11.67 | 10.75 ± 7.31 | −11.10 * | [−16.52, −5.68] | −6.28 * | [−12.01, −0.56] | DTC | DTC (%) = [(ST − DT)/ST] × 100 | 4 m walk with serial-three subtraction task (2-digit) analysed with OptoGait (m/s); walking speed type not specified |

| Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task), Cognitive Training and Simple Exercise | 15 | 21.06 ± 11.26 | 16.54 ± 12.99 | −4.52 * | [−8.41, −0.63] | ||||||

| Chuang et al. 2025 (Taiwan) [42] | Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | 22 | −8.27 ± 11.92 | 1.88 ± 10.67 | 10.15 * | NR | 8.48 §¶ | [2.42, 14.54] § | DTE | DTE (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk with Stroop task, timed with stopwatch (m/s); self-paced walking speed |

| Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 22 | −9.18 ± 8.60 | −6.60 ± 9.19 | 2.58 | NR | ||||||

| Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | 22 | −8.70 ± 11.93 | −2.48 ± 10.77 | 6.22 * | NR | 6.12 §¶ | [0.29, 11.95] § | DTE | DTE (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk with serial-three sub-traction task, timed with stopwatch (m/s); self-paced walking speed | |

| Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 22 | −9.41 ± 10.70 | −8.60 ± 8.16 | 0.81 | NR | ||||||

| Liu et al. 2017 (Taiwan) [43] | Overground Gait Training with Cognitive Dual-Task | 9 | −22.6 ± 11.0 | −15.7 ± 11.3 * | 6.9 * | NR | −2.9 §# | [−15.72, 9.92] §# | DTC | DTC (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 4.3 m walk with serial-three subtraction task (3-digit) analysed with GAITRite (cm/s); comfortable walking speed |

| Overground Gait Training with Motor Dual-Task | 9 | −13.9 ± 12.4 | −12.8 ± 14.1 | 1.1 | NR | 0.5 §** | [−9.65, 10.65] §** | ||||

| Conventional Physical Therapy | 10 | −17.6 ± 12.2 | −16.2 ± 9.3 | 1.4 | NR | 3.4 §†† | [−8.52, 15.32] §†† | ||||

| Meester et al. 2019 (UK) [44] | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task | 24 | −13.40 ± 9.31 | −15.80 ± 9.31 | −2.40 | NR | −2.1 § | [−7.52, 3.32] § | DTE | NR | Two-minute walk test with daily life questions (m); self-selected walking speed |

| Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task) | 21 | −10.80 ± 8.71 | −13.70 ± 8.71 | −2.90 | NR | ||||||

| Plummer et al. 2021 (USA) [45] | Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | DTE | DTE (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk with Stroop task, meas-ured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system (m/s); fast walking speed |

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | DTE | DTE (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk with Stroop task, meas-ured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system (m/s); preferred walking speed | |

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | DTE | DTE (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk with Clock task, measured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; (m/s); fast walking speed | |

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| Overground Gait Training with Dual-Task | 17 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | DTE | DTE (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk with Clock task, meas-ured with LEGSys™/Qualysis system; (m/s); preferred walking speed | |

| Overground Gait Training (Single-Task) | 19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| Timmermans et al. 2021 (The Netherlands) [46] | Treadmill-Based C-Mill Therapy | 14 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | DTE | DTE (%) = [(DT − ST)/ST] × 100 | 10 m walk with serial-three subtraction task (m/s); self-selected walking speed |

| Standard Overground FALLS Program | 16 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Study | Post-Intervention Follow-Up | Group | N | Post-Intervention Mean ± SD * | Follow-Up Mean ± SD * | Mean Difference (Within-Group) * | 95% CI of Within-Group Mean Difference * | Mean Difference (Between-Groups) * | 95% CI of Between-Groups Mean Difference * | Measures of Dual-Task Gait Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio et al. 2022 (Brazil) [40] | 5 weeks | Mixed Physical Exercise with Dual-Task | 13 | 1.07 ± 0.43 | 1.00 ± 0.41 | −0.07 | NR | −0.17 † | [−0.45, 0.11] † | 10 m walk test with verbal fluency task; comfortable walking speed |

| Mixed Physical Exercise (Single-Task) | 13 | 1.27 ± 0.33 | 1.17 ± 0.27 | −0.10 | ||||||

| Chuang et al. 2025 (Taiwan) [42] | 4 weeks | Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | 22 | 0.98 ± 0.18 | 1.01 ± 0.16 | 0.03 | NR | 0.09 † | [−0.035, 0.21] † | 10 m walk with Stroop task, timed with stopwatch; self-paced walking speed |

| Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 22 | 0.89 ± 0.23 | 0.92 ± 0.24 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Multimodal Training with Dual-Task | 22 | 0.94 ± 0.18 | 0.97 ± 0.19 | 0.03 | NR | 0.05 † | [−0.078, 0.18] † | 10 m walk with serial-three subtraction task, timed with stopwatch; self-paced walking speed | ||

| Multimodal Training (Single-Task) | 22 | 0.87 ± 0.22 | 0.92 ± 0.23 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Meester et al. 2019 (UK) [44] | 11 weeks | Treadmill Gait Training with Dual-Task | 24 | 0.702 ± 0.287 | 0.740 ± 0.059 | 0.038 | NR | 0.048 †‡ | [0.011, 0.085] † | Two-minute walk test with daily life questions; self-selected walking speed |

| Treadmill Gait Training (Single-Task) | 21 | 0.664 ± 0.281 | 0.692 ± 0.062 | 0.028 | ||||||

| Timmermans et al. 2021 (The Netherlands) [46] | 52 weeks | Treadmill-Based C-Mill Therapy | 14 | 0.76 ± 0.29 | 0.74 ± 0.31 | −0.02 | NR | −0.08 † | [−0.3, 0.14] † | 10 m walk with serial-three subtraction task; self-selected walking speed |

| Standard Overground FALLS Program | 16 | 0.80 ± 0.26 | 0.82 ± 0.28 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alvarez, G.; Sousa, I.; Trindade, M.E.; Pereira, R.; Rosa, S.; Patrício, C.; Gonçalves, R.S. Effectiveness of Exercise Interventions for Improving Dual-Task Gait Speed in People with Stroke Sequelae: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12697. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312697

Alvarez G, Sousa I, Trindade ME, Pereira R, Rosa S, Patrício C, Gonçalves RS. Effectiveness of Exercise Interventions for Improving Dual-Task Gait Speed in People with Stroke Sequelae: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12697. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312697

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarez, Guilherme, Inês Sousa, Maria Eduarda Trindade, Rúben Pereira, Sara Rosa, Cristina Patrício, and Rui Soles Gonçalves. 2025. "Effectiveness of Exercise Interventions for Improving Dual-Task Gait Speed in People with Stroke Sequelae: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12697. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312697

APA StyleAlvarez, G., Sousa, I., Trindade, M. E., Pereira, R., Rosa, S., Patrício, C., & Gonçalves, R. S. (2025). Effectiveness of Exercise Interventions for Improving Dual-Task Gait Speed in People with Stroke Sequelae: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12697. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312697