1. Introduction

The convergence of powerful Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) and the global ubiquity of digital communication platforms is fundamentally reshaping human interaction. GenAI models can create novel, high-fidelity content—including text, code [

1,

2,

3,

4], audio, and video [

5,

6,

7]—offering the potential to make online environments more immersive and functional. This technological shift, occurring alongside the widespread adoption of platforms like video conferencing systems, Augmented/Virtual Reality (AR/VR) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], and social networks [

13,

14,

15] presents a transformative opportunity to dismantle longstanding barriers to global communication, most notably those of language [

16,

17]. Within this domain, “Video Translation”—also known as Video-to-Video or Face-to-Face Translation—represents an emerging paradigm of significant interest [

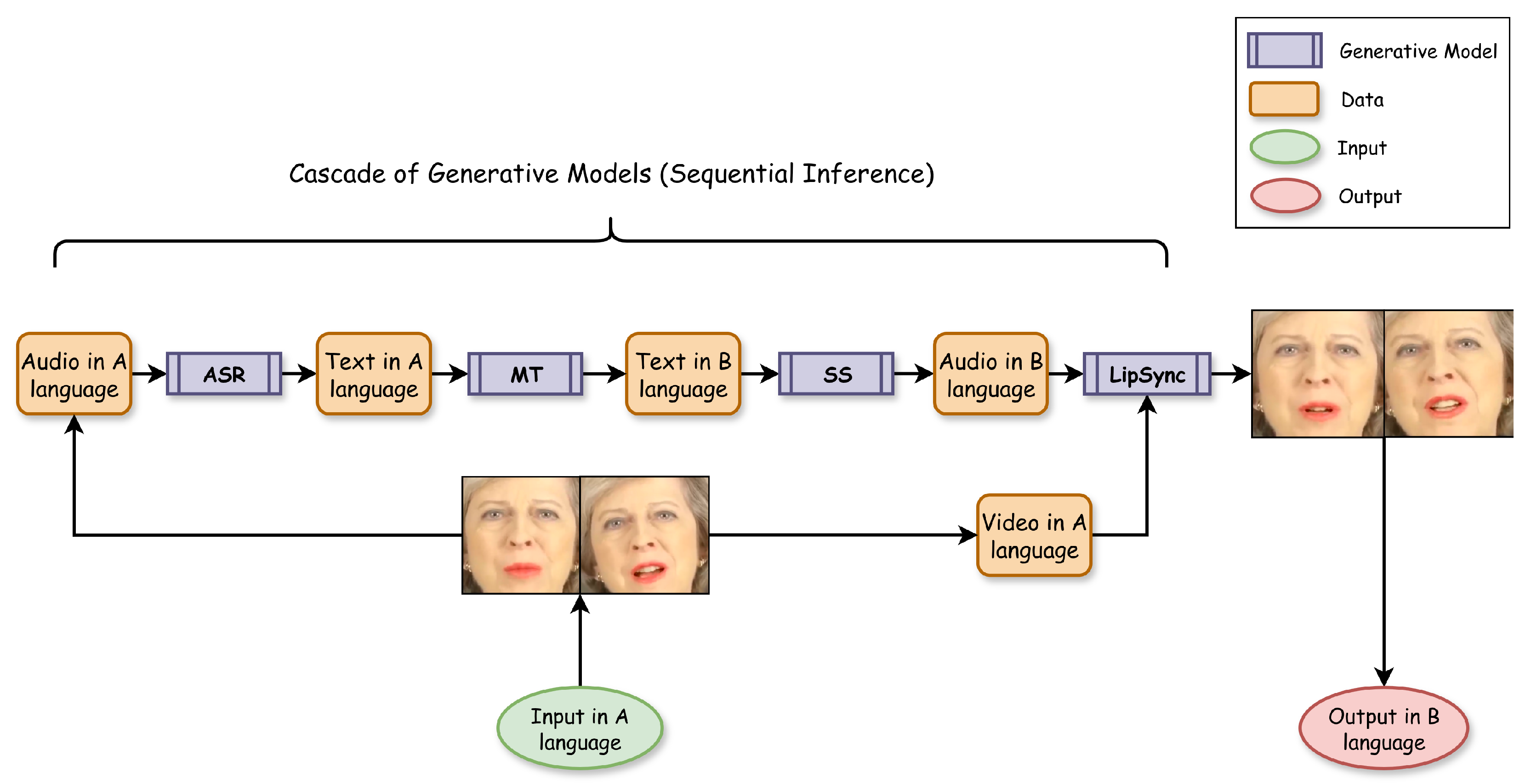

18]. Video translation aims to deliver a seamless multilingual experience by holistically translating all facets of human expression. This process involves converting spoken words, preserving the speaker’s vocal tone and style, and critically, synchronizing their lip movements with the translated speech. Such a comprehensive translation fosters more natural and fluid conversations, providing immense value to international business, global academic conferences, and multicultural social engagements. Achieving this requires end-to-end pipelines that integrate multiple GenAI models for tasks such as automatic speech recognition (ASR), machine translation (MT), text-to-speech (TTS) synthesis, and lip synchronization (LipSync), as illustrated in

Figure 1.

However, the practical deployment of these complex, multi-stage pipelines in real-time, large-scale applications is hampered by formidable system-level engineering challenges that have not been adequately addressed in existing research. GenAI models are computationally intensive, necessitating high-performance hardware like GPUs for timely execution. This requirement is magnified in real-time environments like video conferencing, giving rise to two primary bottlenecks:

- 1.

Latency: The sequential execution of multiple deep learning models introduces significant processing delays. Each stage in the cascade adds to the total inference time, making it difficult to achieve the low-latency throughput required for smooth, uninterrupted conversation.

- 2.

Scalability: In a multi-user video conference, a naive implementation would require each participant to concurrently process video streams from all other speakers. This approach results in a computational complexity of O(N2), which is prohibitively expensive and technically unmanageable, even for a small number of participants (N).

While many studies focus on improving individual models (model-level optimization), a distinct research gap exists in developing architectural and protocol-level solutions that enable these systems to perform effectively in real-time, multi-user settings (system-level optimization). While architectural primitives like turn-taking and batching are known in distributed systems, their specific synthesis and application to solve the unique computational and semantic challenges of real-time generative video translation remains an open and critical research area. To address this critical gap and facilitate the practical deployment of video translation and similar GenAI pipelines, this paper introduces a system-level framework. This work makes the following primary contributions:

We introduce a new System Architecture designed to enable the scalable deployment of generative pipelines in multi-user, video-conferencing environments. The key innovations of this architecture are:

- -

A Token Ring mechanism for managing speaker turns, which reduces the system’s computational complexity from O(N2) to a linear O(N), thereby ensuring scalability.

- -

A Segmented Batched Processing protocol with inverse throughput thresholding, which provides a mathematical framework for managing latency and achieving near real-time performance.

We provide an empirical validation of our framework through a Proof-of-Concept implementation. This study includes a performance analysis across both commodity and enterprise hardware, and a subjective evaluation with user study to confirm the system’s practical viability and user perception.

This manuscript is a substantially extended version of our preliminary work presented at the 25th International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications [

18]. While the conference paper introduced the proof-of-concept, this journal article provides a significant and novel contribution by establishing the complete theoretical and empirical foundation for the proposed framework. The key advancements in this work include: (1) a formal, mathematical methodology with algorithmic pseudocode for our architecture and protocols; (2) a comprehensive, multi-tiered objective performance evaluation across commodity, cloud, and enterprise-grade hardware that empirically validates our real-time processing claims; and (3) a statistically robust subjective evaluation based on a tripled participant pool (N = 30) with new metrics that confirm the user-acceptability of our system’s core design.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the literature on key technologies and real-time multimedia systems.

Section 3 explains our proposed system architecture.

Section 4 describes the proof-of-concept implementation and the experimental setup.

Section 5 presents and analyzes the detailed results from our technical and user-based evaluations.

Section 6 discusses the implications of our findings, and

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

The ability to seamlessly translate spoken language in real-time is a long-standing goal in human-computer interaction, and modern Speech-to-Speech Translation (S2S) systems represent a significant step towards achieving it. The conventional S2S framework operates as a cascaded pipeline, beginning with an Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) module to transcribe speech into text. This text is then translated into a target language by a Machine Translation (MT) component, and finally vocalized by a Speech Synthesis (SS) or Text-to-Speech (TTS) system. Each stage of this pipeline has been profoundly enhanced by deep learning. Neural ASR architectures have achieved robust performance even in challenging acoustic conditions [

19,

20,

21], while Neural Machine Translation (NMT) has become the standard, far exceeding the quality of earlier statistical methods [

22,

23]. The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) has further advanced the state-of-the-art, enabling more contextually nuanced translations and even end-to-end multilingual capabilities [

2,

24,

25]. In parallel, neural TTS systems can now generate highly natural and expressive speech, with zero-shot voice cloning techniques allowing for the preservation of a speaker’s unique vocal identity [

26,

27]. These concurrent advances have established a strong foundation for high-fidelity audio translation, with multimodal generative AI now being explored for complex conversational simulations in fields like medical education [

28].

For video-based communication, audio translation alone is insufficient. Achieving a truly immersive experience requires synchronizing the speaker’s lip movements with the translated audio, a task handled by Talking Head Generation or Lip Synchronization models. A critical requirement for these models within a video translation pipeline is language independence, ensuring that the visual output is driven purely by the audio phonemes rather than the semantics of a specific language. Foundational work in this area demonstrated the feasibility of language-agnostic lip-sync using neural networks, setting the stage for subsequent research [

29]. Early successes were dominated by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which proved effective at generating realistic facial textures and movements [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. More recently, the field has seen a paradigm shift towards Diffusion-based models, which often yield higher-quality and more stable results [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41], and models based on Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs), which excel at creating photorealistic, view-consistent 3D talking heads [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. Beyond mere synchronization, research has also explored enhancing the expressiveness of these models, for instance, by enabling control over the emotional affect of the generated face [

48]. The performance of these systems is evaluated using a wide range of metrics, from visual fidelity to the analysis of underlying multimodal signals, such as the neural correlates of lip-sync imagery [

49]. The generalizability of these models across diverse languages remains a key area of investigation, confirming its importance for global applications [

50].

While individual component models are well-researched, the integration of these parts into complete, end-to-end Video Translation systems is a less explored domain. Early, pre-neural attempts demonstrated the concept [

51], while later work discussed the potential of face-to-face translation without providing a full system implementation for real-world use [

29]. Some studies have integrated multilingual TTS with lip-syncing but did not focus on the practical challenges of deployment [

52]. A notable recent approach, TransFace, proposed an end-to-end model to avoid cascading separate modules [

53]. However, such end-to-end systems can sacrifice the modularity needed for independent component upgrades and fine-grained control. Our own prior work has focused on achieving low-latency performance but did not address the broader system-level scalability challenges inherent in multi-user applications.

A critical synthesis of this literature reveals a distinct trajectory: while the individual component technologies for video translation have achieved remarkable maturity, the focus on holistic, deployable systems remains underdeveloped. Research has produced highly effective models for each stage of the pipeline, from robust ASR and massively multilingual MT to high-fidelity, zero-shot TTS [

21,

22,

26]. Similarly, the field of lip synchronization has rapidly evolved from foundational GAN-based methods to more photorealistic Diffusion and NeRF-based models [

30,

40,

42]. However, integrating these components into a functional whole presents significant engineering challenges that are often addressed in isolation. For instance, some end-to-end systems sacrifice the modularity required to easily upgrade these rapidly evolving components [

53], while other system-level work has focused primarily on mitigating latency for a single user without addressing the critical challenge of multi-user scalability [

54]. This creates a clear research gap: the need for a comprehensive, system-level framework that is both modular and explicitly designed to solve the dual, interconnected problems of real-time latency and quadratic scalability inherent in any practical, multi-user deployment.

Despite these advances in generative models, a significant research gap persists in the system-level engineering required for deploying these pipelines in real-time, multi-user environments like video conferencing. This paper directly addresses this gap by proposing and empirically validating a novel framework designed specifically to make real-time video translation feasible, scalable, and efficient for real-world deployment.

3. Methodology

The primary contribution of this work is a comprehensive, system-level framework designed to bridge the gap between the potent capabilities of generative AI models and their practical application in real-time, multi-user communication systems. Our methodology is not focused on model-level optimization but rather on the architectural and protocol-level engineering required to make such systems feasible, scalable, and efficient. This section provides a detailed exposition of this framework, beginning with the foundational generative pipeline that serves as our testbed, followed by an in-depth analysis of our core architectural and protocol-level innovations.

3.1. GenAI Pipeline

To empirically validate our system-level framework, we first implemented a modular, end-to-end pipeline for the task of video translation. The choice of a modular design is deliberate; it ensures that each functional component can be independently upgraded as more advanced models become available, thereby future-proofing the architecture. The pipeline’s objective is to process an input video of a speaker and generate a semantically equivalent output where the speech is translated and the lip movements are synchronized to the new audio, while preserving the original vocal identity. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the pipeline comprises four discrete, sequential stages:

- 1.

Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR): The pipeline ingests the raw audio stream from the input video. An ASR model performs transcription, converting the spoken phonemes into a textual representation in the source language.

- 2.

Machine Translation (MT): The source-language text is then passed to a multilingual MT model. This component is responsible for translating the text to the desired target language while preserving the original meaning and context.

- 3.

Speech Synthesis (SS): A Text-to-Speech (TTS) model, critically equipped with zero-shot voice cloning capabilities, synthesizes the translated text into an audio waveform. The voice cloning functionality is essential for preserving the speaker’s unique vocal timbre and prosody, which is paramount for maintaining identity and providing a naturalistic user experience.

- 4.

Lip Synchronization (LipSync): Finally, a language-agnostic LipSync model receives two inputs: the original, silent video frames and the newly synthesized target-language audio. It then generates a new video by modifying the speaker’s mouth region to synchronize precisely with the translated audio, completing the video translation process.

3.2. System-Level Challenges

A naive implementation of the above pipeline within a video conferencing application would fail due to two fundamental and prohibitive system-level challenges. A core part of our methodology is to first formally define these challenges to motivate our subsequent solutions.

Challenge 1: Cumulative Latency. The sequential, cascaded execution of four deep learning models results in a significant cumulative processing delay. The total inference time is the sum of the latencies of each stage (). In real-time communication, which is perceptually sensitive to delays exceeding a few hundred milliseconds, this cumulative latency leads to an unacceptable Quality of Service (QoS) degradation, destroying conversational fluidity.

Challenge 2: Quadratic Scalability. In a multi-user environment with N participants, a brute-force architecture would require each of the N participants to maintain concurrent processing streams to translate video from all other speakers. This creates a demand for total processing instances, resulting in a computational complexity of . This quadratic growth is computationally intractable and economically unviable, making the system unscalable beyond a trivial number of users.

3.3. Proposed System Architecture

Our solution begins with a robust system architecture based on the principle of

decoupling. We separate the user-facing application logic from the intensive computational workload. This design pattern enhances modularity, maintainability, and scalability. As shown in

Figure 2, the architecture comprises four distinct layers:

Server Layer: This layer represents the core video conferencing infrastructure (e.g., signaling servers) responsible for session management and establishing communication channels between clients.

Client Layer: This is the user-facing application (e.g., any WebRTC-based video conferencing client). Its responsibilities are to manage user interaction, handle media stream encoding/decoding, and render the final video.

Processing Layer: This intermediary orchestration engine is the core of our solution. It is a stateless service that manages a dynamic pool of GPU resources. It intercepts media streams, allocates pipeline instances on demand, and routes the translated output to the correct recipients.

User Layer: This abstract layer represents the human participants who interact with the Client Layer and specify their desired target language for translation.

Figure 2.

The proposed four-layer system architecture. This design decouples the user-facing client from the back-end Processing Layer, which acts as an orchestration engine for a pool of GPU resources.

Figure 2.

The proposed four-layer system architecture. This design decouples the user-facing client from the back-end Processing Layer, which acts as an orchestration engine for a pool of GPU resources.

3.4. The “Token Ring” Mechanism

To solve the quadratic scalability problem defined in

Section 3.2, we introduce a novel turn-taking protocol we term the “Token Ring” mechanism. This protocol is not merely a heuristic but a structured approach to resource management that fundamentally alters the system’s computational complexity.

3.4.1. Formal Cost Modeling and Complexity Analysis

To provide a rigorous justification for this mechanism, we first define our terms and then formally model the computational cost of the system.

Definitions

Let be the total number of participants in the meeting, where .

Let C be the constant representing the computational cost (e.g., GPU resource allocation) of a single, complete video translation pipeline instance.

Let P be the total system cost, defined as the aggregate cost of all concurrently running pipeline instances.

Scenario 1: The Naive (Brute-Force) System

In an unmanaged system, each of the

N participants must have the capacity to process incoming streams from all other

participants. The total system cost,

, is therefore the product of the number of participants and the number of streams each must process:

As , the cost is dominated by the quadratic term, establishing a computational complexity of . This quadratic growth renders the system computationally intractable and economically unviable for any non-trivial number of participants.

Scenario 2: The Generalized Token Ring System

Our proposed mechanism designates one participant as the Active Speaker and the remaining as Passive Listeners. The key insight is that the system cost is no longer a function of the total number of participants, but of the diversity of target languages requested.

Generalized Model

Let L be the set of unique target languages selected by the passive listeners.

Let be the cardinality of this set, representing the number of distinct target languages.

The value of k is bounded such that .

The total number of required pipeline instances is now equal to

k, as all listeners requesting the same target language can be served by a single, shared pipeline instance. The total system cost,

, is therefore:

Complexity Analysis of Boundary Conditions

Worst-Case Complexity: The worst case occurs when every passive listener selects a unique target language. In this scenario, . The cost becomes , establishing a clear upper bound with a linear computational complexity of .

Best-Case Complexity: The best case occurs when all passive listeners select the same target language. In this scenario, . The cost becomes , which is a constant cost independent of the number of users. This establishes a lower bound with a complexity of . Using Asymptotic notation, we can state the best-case complexity is also , indicating a constant time complexity.

This formal analysis demonstrates that the Token Ring mechanism transforms an intractable problem into a highly manageable linear problem, which in many practical scenarios trends towards a constant-time solution.

To formalize the operational logic of the Token Ring mechanism, we present its core orchestration algorithm in Algorithm 1. This algorithm executes within the Processing Layer upon any change in the active speaker, managing the allocation, reuse, and deallocation of GPU pipeline instances to maintain a minimal computational footprint.

| Algorithm 1: Token Ring Stream Orchestration Protocol |

- 1:

Input: (participants), (speaker), (GPU pool) - 2:

State: (language to pipeline mapping) - 3:

Output: Updated routing and allocation - 4:

function UpdateOrchestration(, s, ) - 5:

Route ▷ Speaker bypasses processing - 6:

▷ Required languages - 7:

▷ Count: - 8:

for all do ▷ Allocate new pipelines - 9:

if then - 10:

if then - 11:

Alloc - 12:

Init - 13:

- 14:

else - 15:

LogError continue - 16:

end if - 17:

end if - 18:

end for - 19:

for all do ▷ Route to listeners - 20:

if then - 21:

- 22:

Route; Route - 23:

end if - 24:

end for - 25:

▷ Deallocate stale pipelines - 26:

for all do - 27:

- 28:

Decommission; Dealloc - 29:

- 30:

end for - 31:

Assert: ▷ cost - 32:

end function - 33:

▷ Complexity: Time , Space where

|

Algorithm 1 implements the Token Ring mechanism, executing on each speaker transition. Three invariants ensure correctness: (1) speaker

s receives bypass stream (no self-translation), (2)

L determines minimal pipeline allocation (no redundancy), and (3) stale deallocation (lines 20–24) maintains

, preserving

complexity from

Section 3.4. The key insight: transform from participant-centric allocation (

instances) to language-centric (

k instances only). With linguistic homogeneity (e.g., bilingual meetings), this approaches

as

.

3.4.2. Justification and Design Rationale

The enforcement of a single active speaker may initially appear to be a constraint on the natural, fluid dynamics of conversation where interruptions and overlapping speech can occur. However, this design choice is a deliberate and necessary trade-off made to ensure intelligibility in a translated context. In the target domain of professional, educational, or formal multilingual communication, effective information exchange already relies on clear, sequential turn-taking. Simultaneous speech from multiple parties, when translated into multiple languages, would result in a cacophony of audio streams, rendering the conversation unintelligible for all listeners. Therefore, the Token Ring mechanism does not impose an unnatural constraint; rather, it formalizes an existing social protocol for coherent communication and leverages it as an architectural cornerstone for achieving computational tractability and ensuring a high Quality of Experience (QoE).

3.5. Segmented Batched Processing

To solve the latency problem, we developed a protocol that manages the high intrinsic processing delay of the pipeline to deliver a perceptually real-time user experience. Our analysis deliberately isolates computational latency from network latency, a standard practice for modeling system performance.

3.5.1. System Performance Characterization

Our protocol is based on a rigorous characterization of the pipeline’s performance.

Definitions

Through empirical analysis, we model the behavior of

as a piecewise function defined by a hardware-dependent constant, the

System Threshold (). This threshold marks the transition point between two operational regimes:

In the System Lag Regime, system overheads dominate, and the pipeline cannot keep pace with real-time. In the Real-Time Regime, initial overheads are amortized, and the processing time

grows sub-linearly, a behavior we empirically model as

.

3.5.2. The Real-Time Viability Condition

To operationalize this model, we define the

Reciprocal Throughput,

, a dimensionless metric that normalizes processing time against real-time duration:

The value of

directly indicates system viability:

implies the system is falling behind, while

implies it is at or ahead of real-time. Continuous, uninterrupted playback is only possible if the system operates consistently in the

state. This leads us to our core operational requirement:

We define the

Optimal Segment Duration () as the minimum value of

t that satisfies this condition, ensuring both stability and minimal initial latency.

3.5.3. Overlapping Buffering

Once

is determined for a given hardware configuration, the protocol operationalizes Equation (

5) by segmenting the input stream into fixed-duration chunks of length

and employing a strategy of overlapping buffering. This guarantees a continuous stream for the listener after a single, initial buffering event, transforming a system with high intrinsic latency into one that delivers a perceptually near real-time experience.

The operational logic of the segmented processing protocol is detailed in Algorithm 2. This algorithm runs on a dedicated GPU instance within the Processing Layer. It continuously reads segments of optimal duration (

) from the active speaker’s stream and processes them asynchronously, using a queue to buffer the output and ensure smooth, uninterrupted playback for the listener after an initial startup delay.

| Algorithm 2: Segmented Processing with Overlapping Buffering Protocol |

- 1:

Input: S (input stream), (pipeline), T (segment duration) - 2:

Output: (output stream) - 3:

Precondition: (real-time viable) - 4:

function ProcessStream(S, , T) - 5:

▷ Job queue (FIFO) - 6:

▷ Buffer state - 7:

▷ Segment counter - 8:

while HasData() do - 9:

Read(S,T) ▷ Get segment of length T - 10:

- 11:

AsyncJob ▷ Non-blocking call - 12:

Q.Enqueue - 13:

if then ▷ Initial buffering - 14:

Wait(Q.Front()) ▷ Block on first job - 15:

- 16:

end if - 17:

while Front().Done() do ▷ Stream completed jobs - 18:

Dequeue() - 19:

Write(,Result(θ)) - 20:

end while - 21:

end while - 22:

while do ▷ Drain remaining jobs - 23:

Dequeue() - 24:

Wait - 25:

Write(,Result(θ)) - 26:

end while - 27:

Close - 28:

Assert: no buffering after startup - 29:

end function - 30:

▷ Latency: startup, constant steady-state

|

Algorithm 2 operationalizes the Segmented Batched Processing protocol by implementing a producer-consumer pattern with explicit initial buffering. The algorithm’s correctness depends critically on the precondition that

satisfies the Real-Time Viability Condition (

), as established empirically in

Section 5. The one-time blocking wait in lines 12–15 constitutes the “predictable initial delay” identified in our methodology, after which the overlapping mechanism ensures continuous output: while segment

streams to the listener, segment

is concurrently read from the input, and segment

undergoes pipeline processing. This three-stage overlap is possible precisely because

, meaning processing completes faster than real-time playback. The queue drain phase (lines 23–28) ensures graceful stream termination without data loss. Importantly, the total perceived latency remains bounded at

regardless of stream duration, as the steady-state condition

eliminates all subsequent buffering events, thereby delivering the perceptually smooth experience validated in our subjective evaluation (

Section 5.2).

Justification and Design Rationale

While the ideal for any real-time system is zero latency, the significant computational demands of cascaded generative models make this physically unattainable with current technology. The system designer is therefore faced with a critical engineering trade-off: (a) attempt a continuous, low-latency stream that is highly susceptible to frequent stuttering, buffering, and desynchronization as the pipeline struggles to keep up, or (b) introduce a predictable, one-time latency at the start of a speaking turn in exchange for guaranteed smooth, uninterrupted playback thereafter. From a user experience (UX) and psycholinguistic perspective, the latter is vastly superior. Predictable, initial delays are quickly adapted to by users, whereas intermittent, unpredictable interruptions are highly disruptive and destroy the perception of conversational flow. Our protocol makes the deliberate choice to front-load this unavoidable computational cost, thereby ensuring a high-quality, reliable, and perceptually smooth experience for the duration of the speaker’s turn.

4. Proof-of-Concept & Experimental Setup

This section details the empirical framework designed to validate the theoretical methodology presented in

Section 3. The primary objective is not to build a production-ready, commercial-grade application, but rather to develop a simplified yet functional

Proof-of-Concept (PoC). This PoC serves two crucial purposes: first, as a testbed for rigorously characterizing the performance of our proposed architecture and protocols under controlled conditions; and second, to demonstrate the feasibility of our approach. By maintaining simplicity and leveraging widely available technologies, this PoC is intended to provide a foundational, universal framework that developers and businesses can build upon.

4.1. Software

The PoC was implemented as a complete system, encompassing both the back-end generative pipeline and a front-end user interface to simulate a real-world video conferencing environment.

4.1.1. Models & Libraries

The four-stage video translation pipeline described in

Section 3.1 was implemented using state-of-the-art, open-source models selected for their performance and accessibility. The modular design allows for each component to be independently benchmarked and updated. To ensure full reproducibility—a cornerstone of high-quality scientific research—the exact models and libraries, along with their version numbers, are detailed in

Table 1.

4.1.2. Graphical User Interface

To facilitate subjective evaluation and simulate a realistic user experience, we developed a simple web-based user interface (UI) using React.js, CSS, and HTML. The UI allows users to initiate a simulated video call, select a target language for translation from a dropdown menu, and view the final translated video with synchronized lip movements. Real-time signaling and communication between clients were managed using Socket.io, while peer-to-peer video and audio streaming were implemented with the Simple-Peer (WebRTC) library.

Crucially, the prototype was designed to be platform-agnostic. This ensures that the core processing logic can be integrated into any existing video conferencing platform with minimal modifications, reinforcing the universality of our proposed architecture. The simplicity of the UI is deliberate, focusing squarely on testing the feasibility and perceptual quality of the back-end system.

4.2. Hardware

A key objective of this study is to characterize our system’s performance across a spectrum of computational capabilities, from consumer-grade hardware to enterprise-level infrastructure. This approach demonstrates the accessibility of our framework while also validating its performance in a production-like environment. To this end, we established three distinct hardware testbeds:

Commodity-Tier (Commercial Laptop): An NVIDIA RTX 4060 Laptop GPU was used to represent a typical high-performance consumer or developer machine. Experiments on this tier were run on a local machine.

Cloud/Datacenter-Tier (Google Colab): An NVIDIA T4 GPU, a widely available and cost-effective datacenter card, was used to simulate a common cloud computing environment. The T4 represents a conservative baseline for cloud performance.

Enterprise-Tier (Google Colab Pro): An NVIDIA A100 GPU, a high-performance card designed for demanding AI workloads, was used to represent an enterprise-grade production environment.

This multi-tiered hardware strategy allows us to directly test the hardware-dependent nature of the system threshold (

) and validate the real-time viability of our protocol as defined in

Section 3.5.

4.3. Dataset

For the objective evaluation, we constructed a standardized test dataset to ensure consistent and comparable measurements. The dataset consists of 8-s video clips of speakers from diverse linguistic backgrounds, sourced from public-domain interviews. To systematically analyze the relationship between input duration and processing time (), these 8-s samples were meticulously segmented into clips of five distinct durations: 1, 2, 3, 5, and 8 s. (For all objective inference time analyses, a single benchmark scenario—translating a German-language video into English—was used to provide a consistent performance profile and eliminate language-pair variability as a confounding factor.)

4.4. Evaluation

Our evaluation protocol is divided into two complementary components: an objective analysis of computational performance and a subjective assessment of user experience. All details of the evaluation methodology are consolidated within this section to provide a clear and comprehensive overview of our experimental procedures.

4.4.1. Objective Evaluation

The goal of this evaluation is to empirically measure the performance metrics defined in our methodology (

Section 3.5). We measured two primary metrics: (1)

Inference Time (

), the wall-clock time in seconds required for the entire pipeline to process a video segment of duration

t, and (2)

Reciprocal Throughput (

), calculated as per Equation (

4) (

). The inference time was recorded for the full pipeline and for each individual module to identify bottlenecks. To ensure statistical robustness and account for minor variations, each experiment on each hardware testbed and for each segment duration was iterated three times. The final reported values are the mean and standard deviation of these three runs.

4.4.2. Subjective Evaluation

The goal of this evaluation is to quantify the perceptual quality of the system’s output from an end-user perspective. A pool of 30 participants was recruited to ensure the statistical robustness of our findings. The study involved 30 volunteer participants (18 male, 12 female) aged between 22 and 48 (mean age: 31.5). Participants were recruited from diverse geographical and linguistic backgrounds, including North America, Europe, and the Middle East, ensuring a range of native speakers for languages including English, German, and Turkish. All participants reported high familiarity with standard video conferencing tools but possessed varying levels of expertise in generative AI, representing a general user population rather than a panel of AI experts. This demographic information is provided to improve the transparency and generalizability of our findings.

Participants interacted with the PoC’s user interface, where they were shown translated video clips generated under the specific hardware conditions detailed in

Section 5. They were then asked to rate their experience based on five criteria using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Bad, 2 = Poor, 3 = Fair, 4 = Good, 5 = Excellent). The aggregated results were analyzed using the Mean Opinion Score (MOS) protocol. The five evaluation criteria were designed to provide a holistic assessment of the user experience, as detailed in

Table 2.

This comprehensive experimental setup, encompassing a functional PoC, multi-tiered hardware, and a rigorous dual-pronged evaluation protocol, provides the empirical foundation for the results and analysis presented in the following section.

5. Results & Analysis

This section presents the empirical findings from the comprehensive evaluation protocol detailed in

Section 4. The results are organized into two main parts. First, we present the objective performance analysis, which serves to empirically validate the theoretical models of our system architecture and processing protocols. Second, we present the subjective user experience analysis, which quantifies the perceptual quality of the proof-of-concept and confirms its practical viability from an end-user perspective.

5.1. Objective Performance Analysis

The objective evaluation was designed to rigorously characterize the computational performance of the video translation pipeline across the three distinct hardware tiers. The primary goals were to: (1) validate the piecewise performance model and sub-linear scaling behavior of the pipeline’s inference time, ; and (2) empirically determine the conditions under which the “Real-Time Viability Condition” () is met.

Table 3 presents the full, aggregated results for total pipeline inference time (

) and the calculated Reciprocal Throughput (

) for each hardware testbed across the five video segment durations.

The raw data clearly demonstrates two trends. First, for any given video length, the inference time scales inversely with the computational power of the GPU, with the A100 being significantly faster than the RTX 4060, which is in turn faster than the T4. Second, for all hardware, the increase in inference time is sub-linear with respect to the increase in video length.

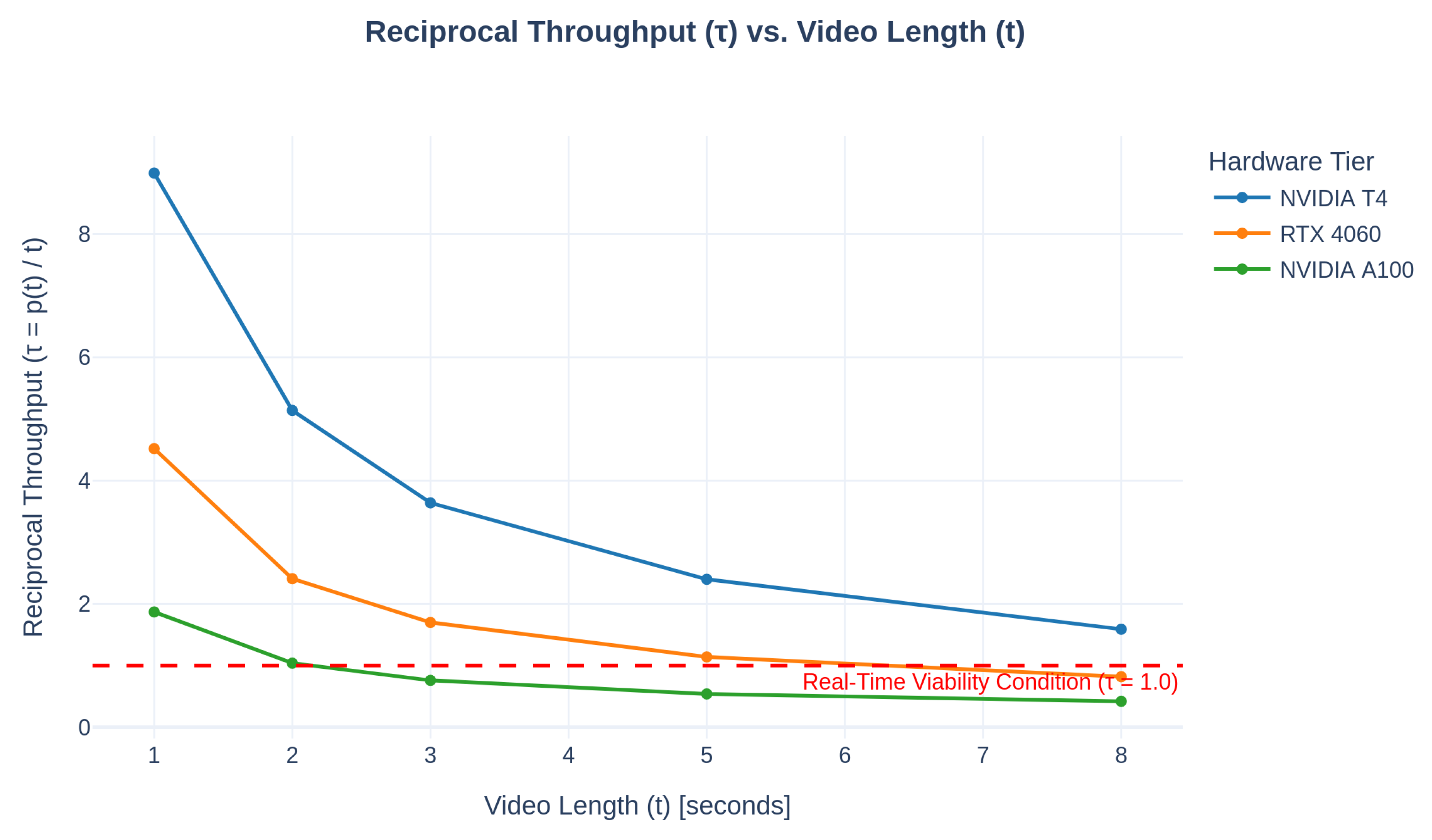

To better visualize these results in the context of our methodology,

Figure 3 plots the Reciprocal Throughput (

) as a function of video duration. This graph is the primary tool for validating our segmented processing protocol.

As predicted by our model (Equation (

5)),

Figure 3 provides direct empirical validation of our protocol. The enterprise-grade A100 GPU crosses the

threshold between

and

s, establishing an optimal segment duration (

) of approximately 3 s for that hardware. The commodity-tier RTX 4060 achieves this condition between

and

s, making

around 8 s. In contrast, the baseline T4 GPU fails to achieve

within the tested 8-s range, operating entirely within the “System Lag Regime.” This directly confirms that the viability of the protocol is hardware-dependent and that smooth, real-time playback is readily achievable on modern commodity and enterprise GPUs.

Furthermore, the data in

Table 3 directly confirms the sub-linear scaling behavior that is foundational to our protocol. The disproportionately high processing time for short 1-s segments reveals the significant impact of fixed overheads from model loading and initialization. However, as video length increases, these initial costs are clearly amortized. For example, on the A100, doubling the video length from 1 s to 2 s increases the total processing time by only 11% (from 1.87 s to 2.08 s), while the final 3 s of video (from 5 s to 8 s) add only 23% to the total time. This flattening of the performance curve is precisely what enables our segmented protocol to work: by processing longer chunks, the system effectively “catches up” and can operate ahead of real-time.

5.2. Subjective User Experience Analysis

Following the objective performance characterization, a subjective evaluation was conducted with 30 participants to assess the perceptual quality of the system’s output. To test the core premise of our segmented processing protocol, participants were shown video clips generated under specific latency conditions corresponding to each hardware tier.

For the baseline NVIDIA T4, which never achieved the real-time condition, users were shown the 8-s clip with its corresponding 12.7-s processing delay to gauge user tolerance for a lagging system. For the RTX 4060 and A100, participants were shown video clips with durations that satisfied the Real-Time Viability Condition ()—specifically, an 8-s clip for the RTX 4060 (6.6 s delay) and a 3-s clip for the A100 (2.3 s delay). This allowed for a direct evaluation of the “Startup Delay Acceptability” (SDA) under conditions where smooth playback is guaranteed.

Table 4 summarizes the Mean Opinion Scores (MOS) for the five criteria. While the model outputs for LSA, MN, VIQ, and VOQ are technically identical across platforms, we report the collected scores for each condition to reflect any potential perceptual differences or biases introduced by the varied user experience.

To provide a clear visualization of the user ratings for the most critical perceptual metric,

Figure 4 presents a bar chart of the mean scores for Startup Delay Acceptability (SDA).

The analysis reveals two key insights. First, the perceptual quality of the generative models themselves was consistent, regardless of the underlying hardware. The high ratings for Vocal Quality (VOQ), with a mean score consistently above 4.5, and positive results for Lip Sync Accuracy (LSA) and Motion Naturalness (MN) confirm the effectiveness of the chosen models. As indicated by the MOS scores, Visual Quality (VIQ) remained the lowest-rated metric across all tests, signifying that visual artifacts from the LipSync model are the primary bottleneck in perceptual quality.

Second, and most critically, the bar chart in

Figure 4 provides direct user validation for our segmented processing protocol by illustrating its hardware-dependent nature. There is a clear and strong positive correlation between hardware performance and user satisfaction with the startup delay. The baseline T4, with a long 12.7 s delay, received a good but comparatively low mean SDA score of 4.15. This score significantly increased to 4.60 for the RTX 4060, which halved the delay to 6.6 s. Finally, the A100, which reduced the startup delay to a near-imperceptible 2.3 s, received an almost perfect mean score of 4.85.

This is a key finding. It provides direct empirical validation for the core trade-off in our protocol: users find the initial, predictable startup delay to be an acceptable price for a subsequent smooth, uninterrupted playback experience. Furthermore, it proves that as hardware capabilities improve, the perceived trade-off diminishes to the point of being a non-issue, confirming that our protocol is not only technically sound but creates a highly satisfactory and user-centric Quality of Experience on modern hardware.

6. Discussion

The results presented in the previous section provide strong empirical validation for our proposed system-level framework. This section moves beyond the raw data to interpret these findings, discuss their broader implications for the field of real-time generative AI systems, and honestly assess the limitations of the current work to guide future research.

6.1. Empirical Validation of the System Architecture & Protocols

Our primary contribution is an architectural and protocol-level solution to the challenges of latency and scalability in multi-user generative AI applications. The objective performance analysis provides three key points of validation for this framework.

First, the sub-linear scaling of inference time (

), as evidenced by the data in

Table 3, is not merely a performance artifact but a fundamental property that our segmented processing protocol is designed to exploit. The initial high overheads for short-duration clips confirm that a naive, continuous streaming approach would be highly inefficient and prone to failure. By demonstrating that these overheads are amortized over longer segments, we have empirically validated the core assumption of our protocol: processing in optimized, fixed-length chunks is demonstrably more efficient.

Second, the multi-tiered hardware evaluation (

Figure 3) confirms that our “Real-Time Viability Condition” (

) is a practical and achievable target. The results draw a clear and actionable distinction between hardware tiers: while the system is

feasible on a baseline cloud GPU like the NVIDIA T4, it becomes

production-ready on both modern commodity hardware (RTX 4060) and enterprise-grade infrastructure (NVIDIA A100). This finding is significant as it provides a clear roadmap for deployment: developers can prototype on accessible hardware, confident that the system will achieve true real-time performance when scaled to production environments, thereby de-risking the adoption of such technologies.

Third, the strong positive rating for Startup Delay Acceptability (SDA) in our subjective evaluation provides crucial user-centric validation for our engineering trade-off. The data confirms that users perceive a system with a predictable, one-time initial latency followed by smooth, uninterrupted playback as a high-quality experience. This psycho-visual finding challenges the conventional wisdom that all latency must be minimized at all costs. Instead, it suggests that for computationally intensive tasks, predictability and reliability of the stream are more critical to the user’s Quality of Experience than the absolute initial delay. This insight has broad applicability beyond video translation to other real-time generative tasks.

Furthermore, our multi-tiered subjective evaluation can be interpreted as an implicit ablation study of our protocol’s primary benefit. The NVIDIA T4 test case, which fails to meet the real-time viability condition (), represents a “control” system where users experience the full, raw processing delay without the guarantee of smooth playback. The RTX 4060 and A100 test cases, which satisfy the condition (), represent the “treatment” system operating as designed. The statistically significant and substantial increase in the Startup Delay Acceptability (SDA) score from the control to the treatment conditions provides direct quantitative evidence of our protocol’s effectiveness in improving the user’s Quality of Experience.

6.2. Analysis of User Perception and Pipeline Quality

The subjective evaluation, now fortified with a larger participant pool, allows for a more confident analysis of the end-user experience. The standout result is the exceptionally high rating for Vocal Quality (VOQ), which, with mean scores consistently above 4.5, indicates that modern zero-shot voice cloning technology is mature enough for practical applications. This success is critical, as preserving the speaker’s vocal identity is paramount for maintaining conversational presence and authenticity.

Conversely, the lowest-scoring metric, Visual Quality (VIQ), points to a clear area for future improvement. The wider distribution of scores for VIQ suggests that while some users were not bothered by visual artifacts, a significant portion found them distracting. This indicates that the chosen LipSync model (Wav2Lip-GAN), while functional, represents the primary bottleneck in perceptual quality. This finding underscores the modularity of our proposed pipeline; the system architecture itself is robust, and as more advanced, diffusion-based or NeRF-based lip-sync models become available, they can be swapped in to directly address this weakness and improve the overall user experience.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

While this work successfully demonstrates a viable system-level framework, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations to provide a clear path for future research.

First, our performance analysis deliberately isolates computational latency from network latency to provide a clean characterization of the system’s processing capabilities. A real-world deployment would need to integrate this architecture with robust network protocols capable of handling jitter, packet loss, and variable bandwidth to ensure a seamless end-to-end experience. Our work provides the computational foundation upon which such a system can be built.

Second, the “Token Ring” mechanism is presented at an architectural level. This study does not prescribe a specific implementation for the token-passing logic (e.g., manual “raise hand” features, automatic voice activity detection, or moderated control). The development and evaluation of these different token management strategies represent a rich area for future work at the intersection of system design and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). The critical contribution of our work is the formal demonstration that any such turn-taking mechanism, once implemented, fundamentally resolves the quadratic scalability problem.

Finally, while our evaluation provides a thorough validation of our framework’s internal performance claims and user acceptability, this study does not include a direct, quantitative comparison against other end-to-end system architectures. Our assessment was designed to prove the effectiveness of our specific architectural contributions using system-level metrics such as Reciprocal Throughput and Startup Delay Acceptability. As the field matures, the establishment of standardized, system-level benchmarking protocols will be a crucial next step, enabling researchers to directly compare the performance, scalability, and efficiency of different architectural approaches.

7. Conclusions

The integration of generative AI into real-time communication systems offers the transformative potential to dissolve language barriers, yet it is hindered by formidable system-level challenges of latency and scalability. This paper has addressed these challenges by introducing a novel, comprehensive framework for the deployment of real-time multilingual video translation. Our primary contributions are twofold: a scalable Token Ring system architecture that reduces the computational complexity of multi-user meetings from an intractable to a manageable , and a Segmented Batched Processing protocol with inverse throughput thresholding, designed to manage the high intrinsic latency of generative pipelines.

Through the development of a proof-of-concept and a rigorous, multi-tiered empirical evaluation, we have validated the efficacy of this framework. Our objective analysis experimentally demonstrated that the system achieves the critical Real-Time Viability Condition () on both modern commodity and enterprise-grade hardware, confirming its feasibility for widespread deployment. Furthermore, our statistically robust subjective evaluation revealed that users find the system’s trade-off of a predictable initial latency for smooth, uninterrupted playback to be highly acceptable, resulting in a positive overall user experience.

While limitations regarding network integration and visual quality remain areas for future model-level and implementation-level research, this work provides a foundational, validated system architecture. By solving the critical bottlenecks of scalability and latency management, this framework offers a practical roadmap for developers and researchers to build the next generation of inclusive, effective, and truly global communication platforms.

Future work will focus on two critical frontiers. First, the integration of more advanced, non-autoregressive generative models for the pipeline’s bottleneck—the LipSync stage. Emerging diffusion-based and NeRF-based talking head models, while computationally demanding, offer superior visual fidelity and could be integrated into our framework to specifically address the limitations in Visual Quality (VIQ) identified in our user study. Our architecture provides the ideal testbed for quantifying the system-level latency trade-offs of these next-generation models. Second, we will explore dynamic, adaptive segmentation protocols. While our current protocol uses a fixed optimal segment duration (), a more sophisticated approach could dynamically adjust the chunk size in real-time based on network conditions and the linguistic complexity of the source content, further optimizing the balance between latency and computational throughput for a truly seamless user experience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.O. and M.S.A.; Methodology, A.R.O.; Software, I.Ş. and A.K.; Validation, I.Ş. and A.K.; Formal Analysis, A.R.O.; Investigation, I.Ş. and A.K.; Resources, E.C.; Data Curation, I.Ş. and A.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.R.O.; Writing—Review & Editing, A.R.O., E.C., I.Ş., A.K., and M.S.A.; Visualization, A.R.O.; Supervision, M.S.A.; Project Administration, A.R.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors agree to share datasets upon requests from readers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to Aktif Bank for their support in facilitating this research. Their provision of advanced computing resources and a conducive working environment was instrumental in the successful completion of this study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Gemini 2.5 Pro (Model ID: gemini-2.5-pro) for the purposes of language polishing, improving clarity and grammatical structure, and refining the discussion points. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Doropoulos, S.; Karapalidou, E.; Charitidis, P.; Karakeva, S.; Vologiannidis, S. Beyond manual media coding: Evaluating large language models and agents for news content analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskooei, A.R.; Babacan, M.S.; Yağcı, E.; Alptekin, Ç.; Buğday, A. Beyond Synthetic Benchmarks: Assessing Recent LLMs for Code Generation. In Proceedings of the 14th International Workshop on Computer Science and Engineering (WCSE 2024), Phuket Island, Thailand, 19–21 June 2024; pp. 290–296. [Google Scholar]

- Acosta-Bermejo, R.; Terrazas-Chavez, J.A.; Aguirre-Anaya, E. Automated Malware Source Code Generation via Uncensored LLMs and Adversarial Evasion of Censored Model. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, J.; Lin, T.; Ma, Q.; Fang, Z.; Wu, Y. An empirical study of the code generation of safety-critical software using llms. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, K. DanceCaps: Pseudo-Captioning for Dance Videos Using Large Language Models. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, Z.; Cai, J.; Xian, W.; Wei, X.; Qin, Y.; Li, Y. Video-Driven Artificial Intelligence for Predictive Modelling of Antimicrobial Peptide Generation: Literature Review on Advances and Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskooei, A.R.; Caglar, E.; Yakut, S.; Tuten, Y.T.; Aktas, M.S. Facial Stress and Fatigue Recognition via Emotion Weighting: A Deep Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Istanbul, Türkiye, 30 June–3 July 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 193–211. [Google Scholar]

- Partarakis, N.; Evdaimon, T.; Katsantonis, M.; Zabulis, X. Training First Responders Through VR-Based Situated Digital Twins. Computers 2025, 14, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todino, M.D.; Pitri, E.; Fella, A.; Michaelidou, A.; Campitiello, L.; Placanica, F.; Di Tore, S.; Sibilio, M. Bridging Tradition and Innovation: Transformative Educational Practices in Museums with AI and VR. Computers 2025, 14, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Mamani, B.; Salas, C. Collabvr: VR testing for increasing social interaction between college students. Computers 2024, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, V.; Sempere, S. Creating Digital Twins to Celebrate Commemorative Events in the Metaverse. Computers 2025, 14, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Faisal, R.; Al-Gindy, A.; Shaalan, K. Artificial Intelligence and Immersive Technologies: Virtual Assistants in AR/VR for Special Needs Learners. Computers 2025, 14, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, S. Patent Keyword Analysis Using Bayesian Factor Analysis and Social Network Visualization in Digital Therapy Technology. Computers 2025, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitema, I.R.; Oskooei, A.R.; Aktaş, M.S.; Riveni, M. Investigating Echo-Chambers in Decentralized Social Networks: A Mastodon Case Study. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Complex Networks and Their Applications, Istanbul, Turkey, 10–12 December 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 316–328. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Qi, H. Research on the Network Structure Characteristics of Doctors and the Influencing Mechanism on Recommendation Rates in Online Health Communities: A Multi-Dimensional Perspective Based on the “Good Doctor Online” Platform. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, N.F.; Marin, A.; Rodrigues, D.L.; Duarte, F.J. Digital Twin and Metaverse in the Context of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Istanbul, Türkiye, 30 June–3 July 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 254–271. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C.; Xu, Z. Large Language Models for Emotion Evolution Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Hanoi, Vietnam, 1–4 July 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiei Oskooei, A.; Caglar, E.; Şahin, I.; Kayabay, A.; Aktas, M.S. Whisper, Translate, Speak, Sync: Video Translation for Multilingual Video Conferencing Using Generative AI. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Istanbul, Türkiye, 30 June–3 July 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.; Malik, M.K.; Mehmood, K.; Makhdoom, I. Automatic speech recognition: A survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 9411–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhavalkar, R.; Hori, T.; Sainath, T.N.; Schlüter, R.; Watanabe, S. End-to-end speech recognition: A survey. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2023, 32, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheddar, H.; Hemis, M.; Himeur, Y. Automatic speech recognition using advanced deep learning approaches: A survey. Inf. Fusion 2024, 109, 102422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLLB Team. Scaling neural machine translation to 200 languages. Nature 2024, 630, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wu, H.; He, Z.; Huang, L.; Church, K.W. Progress in machine translation. Engineering 2022, 18, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Liu, H.; Dong, Q.; Xu, J.; Huang, S.; Kong, L.; Chen, J.; Li, L. Multilingual machine translation with large language models: Empirical results and analysis. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.04675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskooei, A.R.; Yukcu, S.; Bozoglan, M.C.; Aktas, M.S. Repository-Level Code Understanding by LLMs via Hierarchical Summarization: Improving Code Search and Bug Localization. In International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 88–105. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, E.; Davis, K.; Gölge, E.; Göknar, G.; Gulea, I.; Hart, L.; Aljafari, A.; Meyer, J.; Morais, R.; Olayemi, S.; et al. XTTS: A Massively Multilingual Zero-Shot Text-to-Speech Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.04904. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Pu, D.; Huang, M.; Huang, B. Unet-tts: Improving unseen speaker and style transfer in one-shot voice cloning. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Singapore, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 8327–8331. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.N.; Goodell, A.J. Synthetic Patients: Simulating Difficult Conversations with Multimodal Generative AI for Medical Education. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.19941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KR, P.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Philip, J.; Jha, A.; Namboodiri, V.; Jawahar, C. Towards automatic face-to-face translation. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Nice, France, 21–25 October 2019; pp. 1428–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Prajwal, K.; Mukhopadhyay, R.; Namboodiri, V.P.; Jawahar, C. A lip sync expert is all you need for speech to lip generation in the wild. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 484–492. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Liang, K.; Wang, Z.; Ji, S.; Chen, W. MILG: Realistic lip-sync video generation with audio-modulated image inpainting. Vis. Inform. 2024, 8, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hong, J.; Ro, Y.M. Lip to speech synthesis with visual context attentional gan. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 2758–2770. [Google Scholar]

- Vougioukas, K.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. End-to-End Speech-Driven Realistic Facial Animation with Temporal GANs. In Proceedings of the CVPR Workshops, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; Volume 887, pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Das, D.; Biswas, S.; Sinha, S.; Bhowmick, B. Speech-driven facial animation using cascaded gans for learning of motion and texture. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XXX 16. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 408–424. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cun, X.; Cao, M.; Fan, Y.; Wang, X.; Bai, Q.; Wu, B.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y. Styleheat: One-shot high-resolution editable talking face generation via pre-trained stylegan. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, F.T.; Zhang, L.; Shen, L.; Xu, D. Depth-aware generative adversarial network for talking head video generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 3397–3406. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.; Jiang, J.; Yang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, C. OmniHuman-1: Rethinking the Scaling-Up of One-Stage Conditioned Human Animation Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.01061. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Xu, W.; Xie, J.; Feng, W.; Peng, B.; Xing, W. LatentSync: Audio Conditioned Latent Diffusion Models for Lip Sync. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.09262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Chen, G.; Guo, Y.X.; Yang, J.; Li, C.; Zang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, X.; Guo, B. Vasa-1: Lifelike audio-driven talking faces generated in real time. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.10667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhao, W.; Meng, Z.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Difftalk: Crafting diffusion models for generalized audio-driven portraits animation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 1982–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stypułkowski, M.; Vougioukas, K.; He, S.; Zięba, M.; Petridis, S.; Pantic, M. Diffused heads: Diffusion models beat gans on talking-face generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 5091–5100. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; He, J.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, R.; Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Ren, Y.; Yin, X.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, Z. Geneface++: Generalized and stable real-time audio-driven 3d talking face generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.00787. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, B.; Ji, X.; Zhou, K.; Gao, D.; Bo, L.; Cao, X. Vividtalk: One-shot audio-driven talking head generation based on 3d hybrid prior. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.01841. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; Zhong, T.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, J.; Huang, R.; Liu, J.; He, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; et al. MimicTalk: Mimicking a personalized and expressive 3D talking face in minutes. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.06734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Zhong, T.; Ren, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, W.; Huang, J.; Jiang, Z.; He, J.; Huang, R.; Liu, J.; et al. Real3d-portrait: One-shot realistic 3d talking portrait synthesis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.08503. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, A.H.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, J.; Kim, Y.; Park, G.M. Wav2NeRF: Audio-driven realistic talking head generation via wavelet-based NeRF. Image Vis. Comput. 2024, 148, 105104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Cao, J. Multi-Level Feature Dynamic Fusion Neural Radiance Fields for Audio-Driven Talking Head Generation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Guo, H.; Li, Y. Emotionally controllable talking face generation from an arbitrary emotional portrait. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naebi, A.; Feng, Z. The Performance of a Lip-Sync Imagery Model, New Combinations of Signals, a Supplemental Bond Graph Classifier, and Deep Formula Detection as an Extraction and Root Classifier for Electroencephalograms and Brain–Computer Interfaces. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiei Oskooei, A.; Yahsi, E.; Sungur, M.; Aktas, M.S. Can One Model Fit All? An Exploration of Wav2Lip’s Lip-Syncing Generalizability Across Culturally Distinct Languages. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Hanoi, Vietnam, 1–4 July 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, M.; Meier, U.; Yang, J.; Waibel, A. Face translation: A multimodal translation agent. In Proceedings of the AVSP’99-International Conference on Auditory-Visual Speech Processing, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 7–10 August 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.K.; Woo, S.H.; Lee, J.; Yang, S.; Cho, H.; Lee, Y.; Choi, D.; Kim, K.W. Talking face generation with multilingual tts. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 21425–21430. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Huang, R.; Li, L.; Jin, T.; Wang, Z.; Yin, A.; Li, M.; Duan, X.; Huai, B.; Zhao, Z.; et al. TransFace: Unit-Based Audio-Visual Speech Synthesizer for Talking Head Translation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.15197. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiei Oskooei, A.; Aktaş, M.S.; Keleş, M. Seeing the Sound: Multilingual Lip Sync for Real-Time Face-to-Face Translation. Computers 2024, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).