Enhancing Formability of High-Inclination Thin-Walled and Arch Bridge Structures via Tilted Laser Wire Additive Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

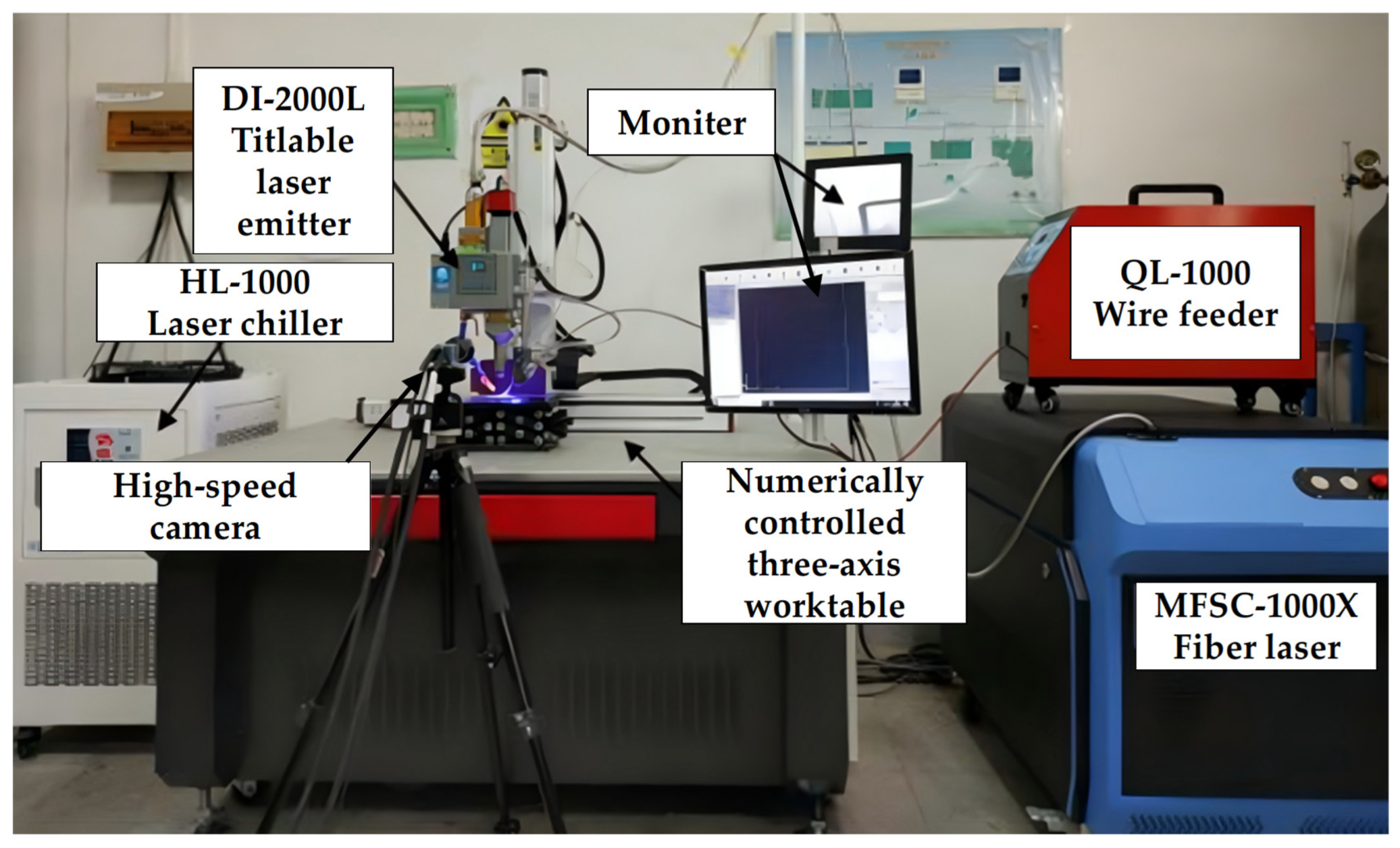

2.1. Materials and Equipment

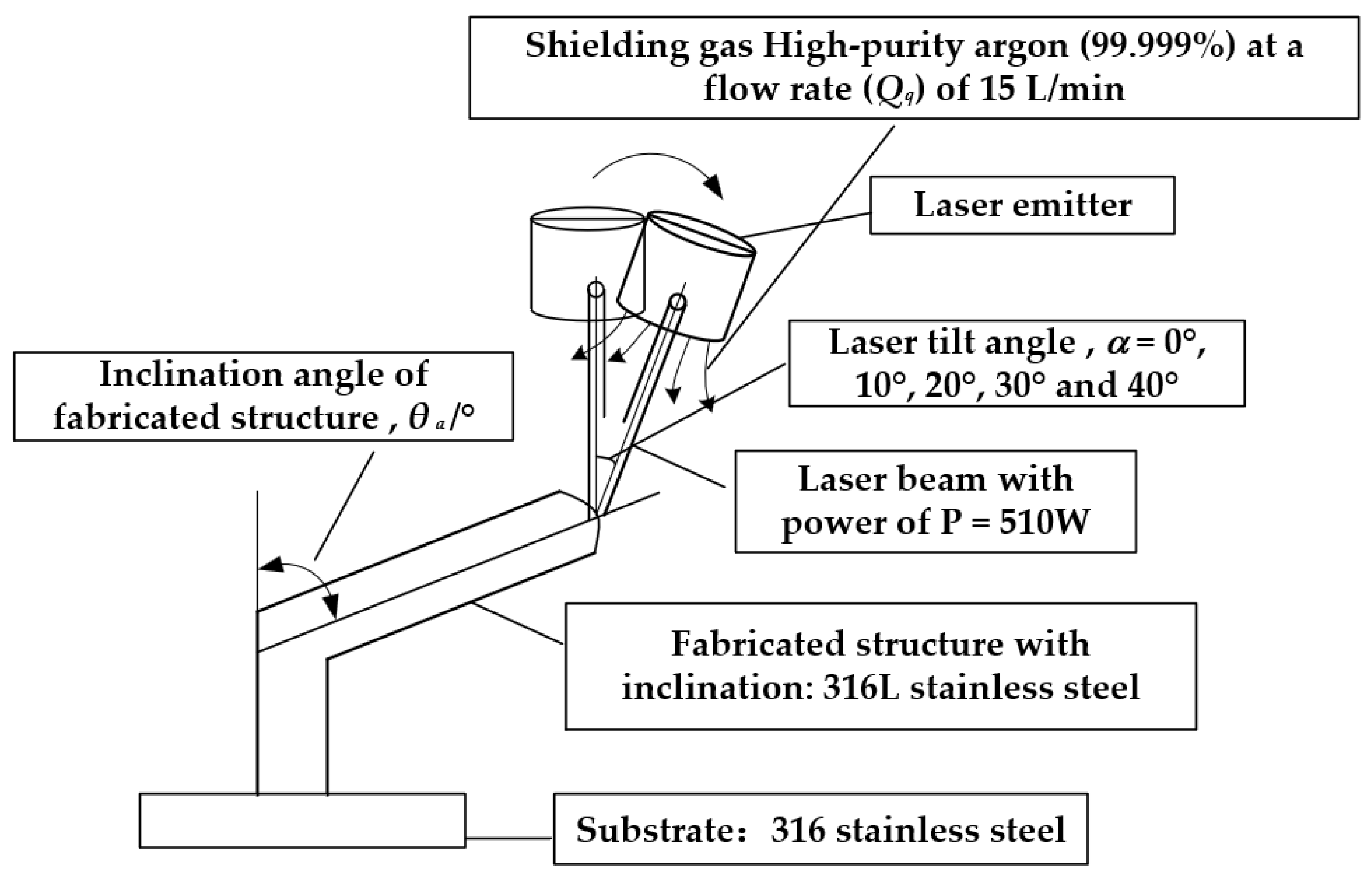

2.2. Laser Tilt Angle Setup

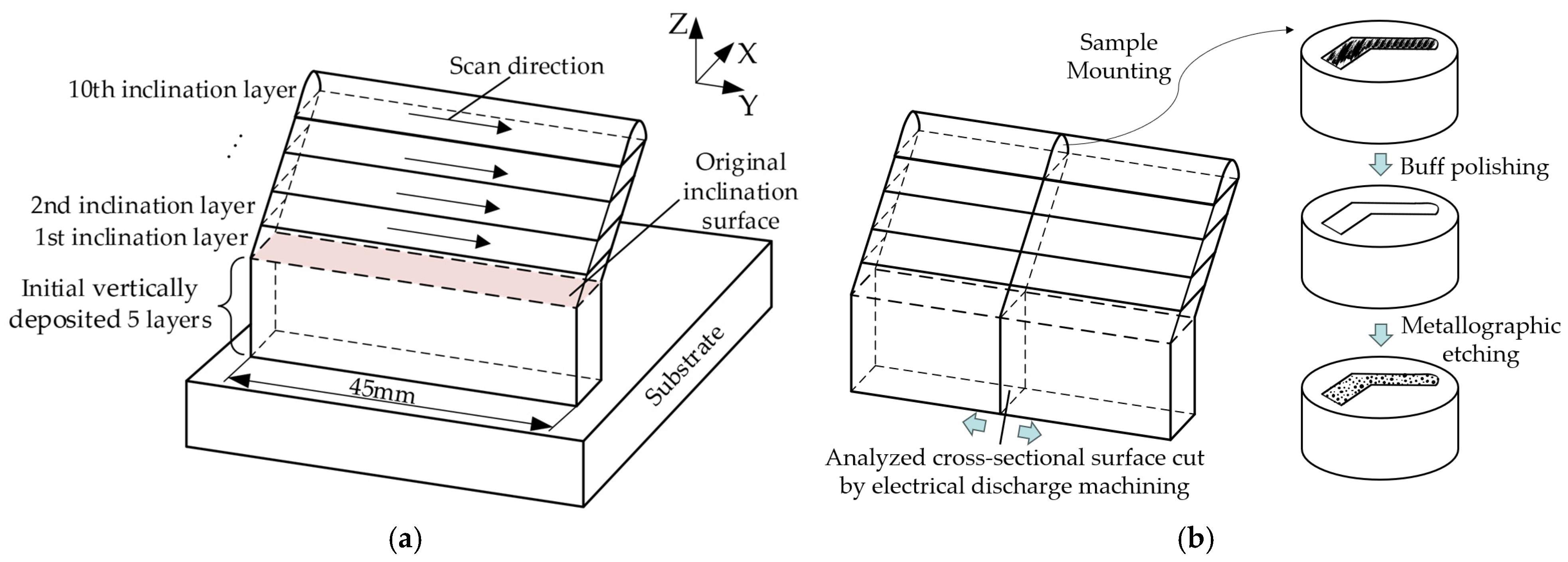

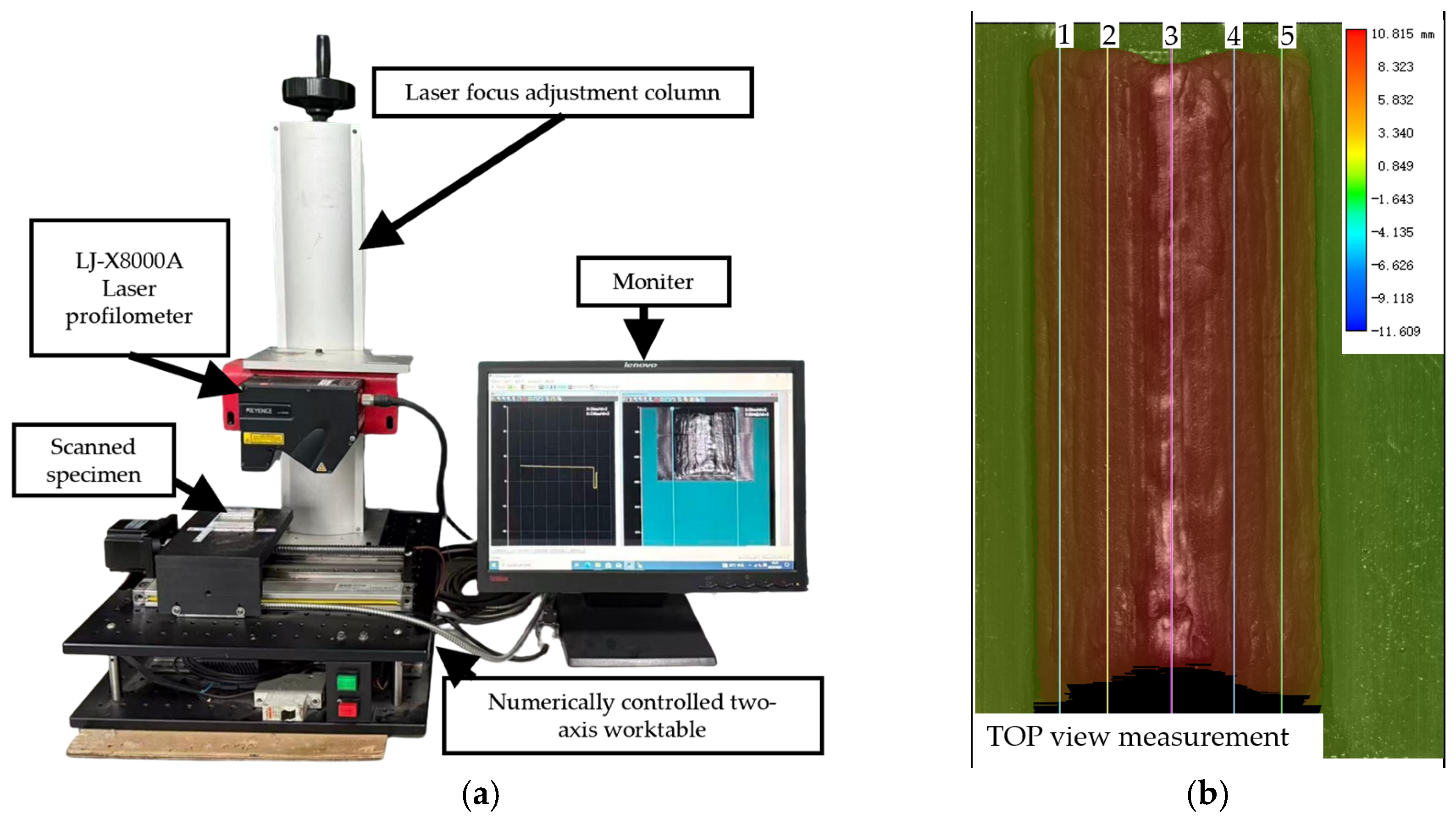

2.3. Fabrication Strategy and Characterization

3. Results

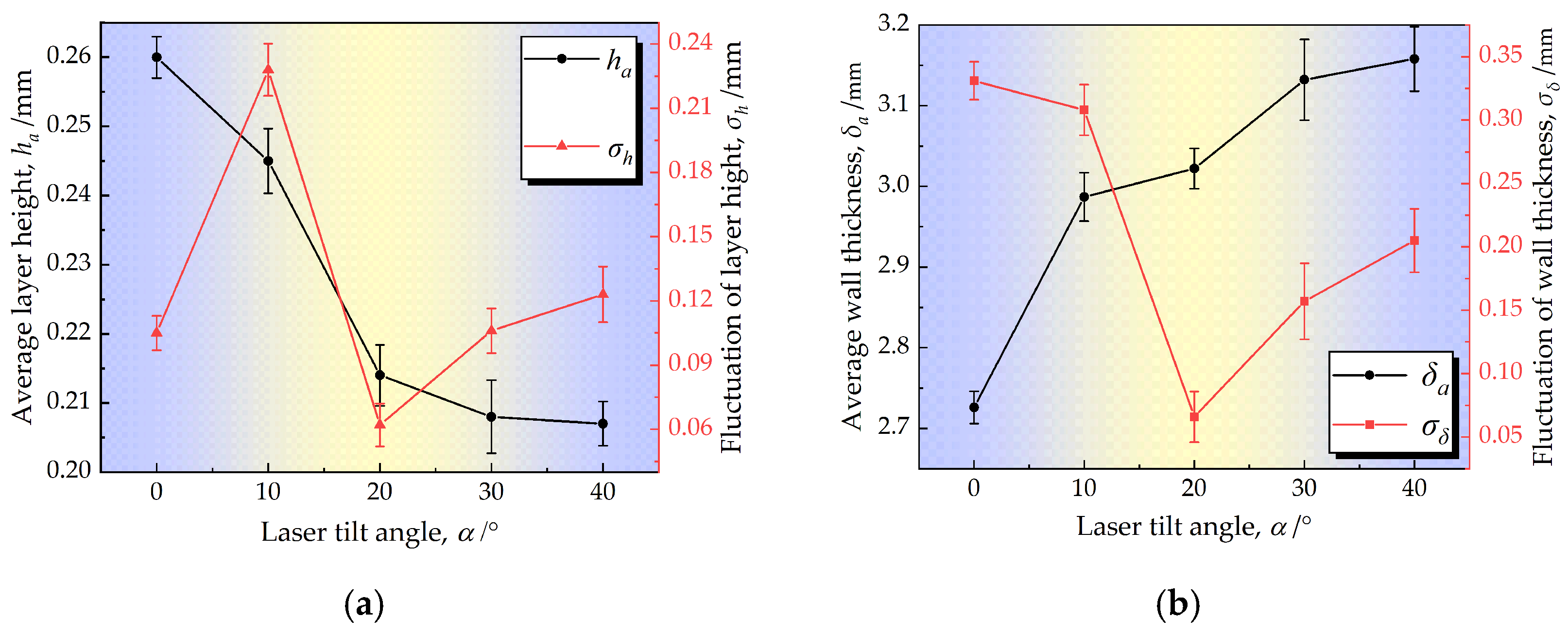

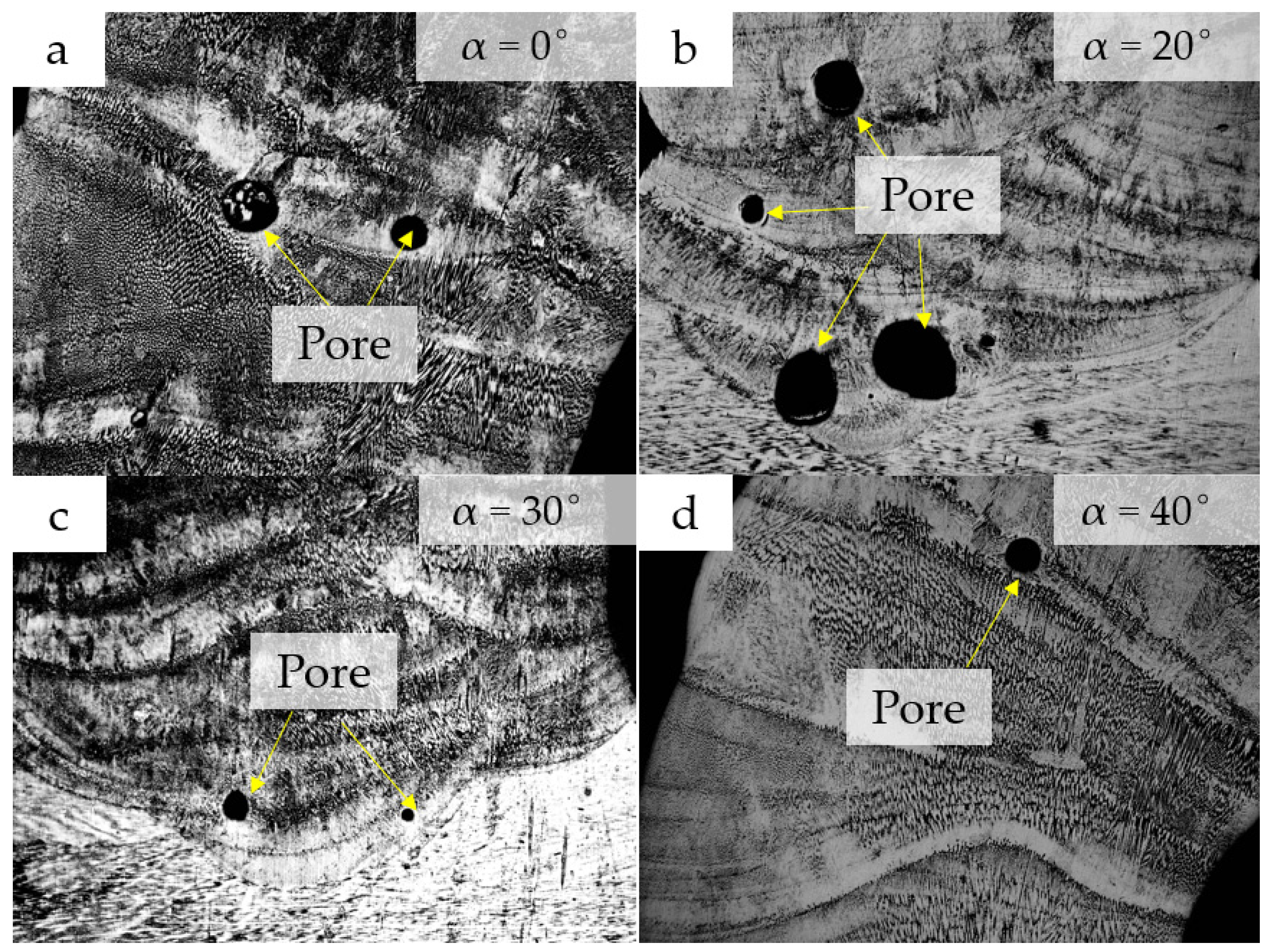

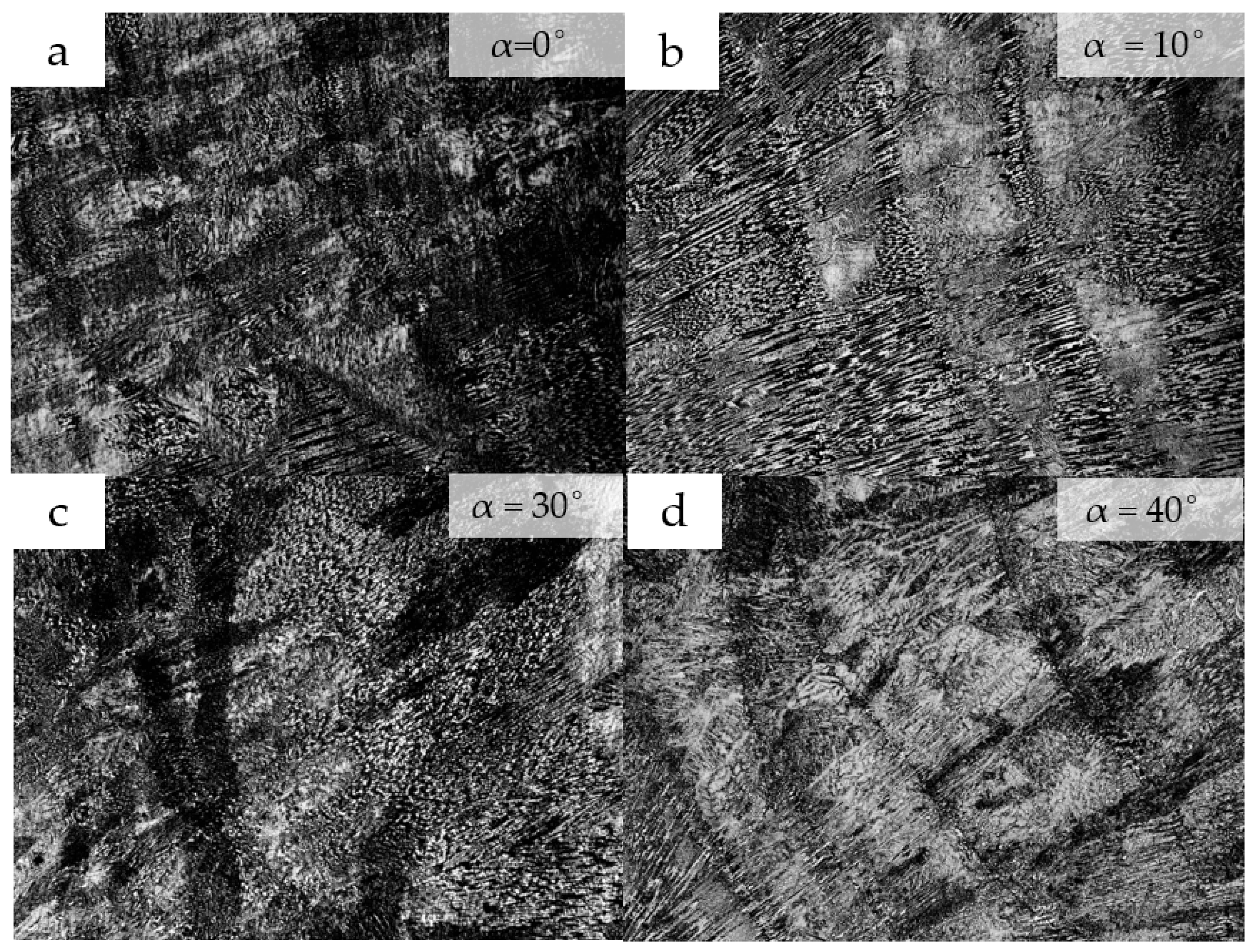

3.1. Effect of Laser Tilt Angles on Deposition Geometry

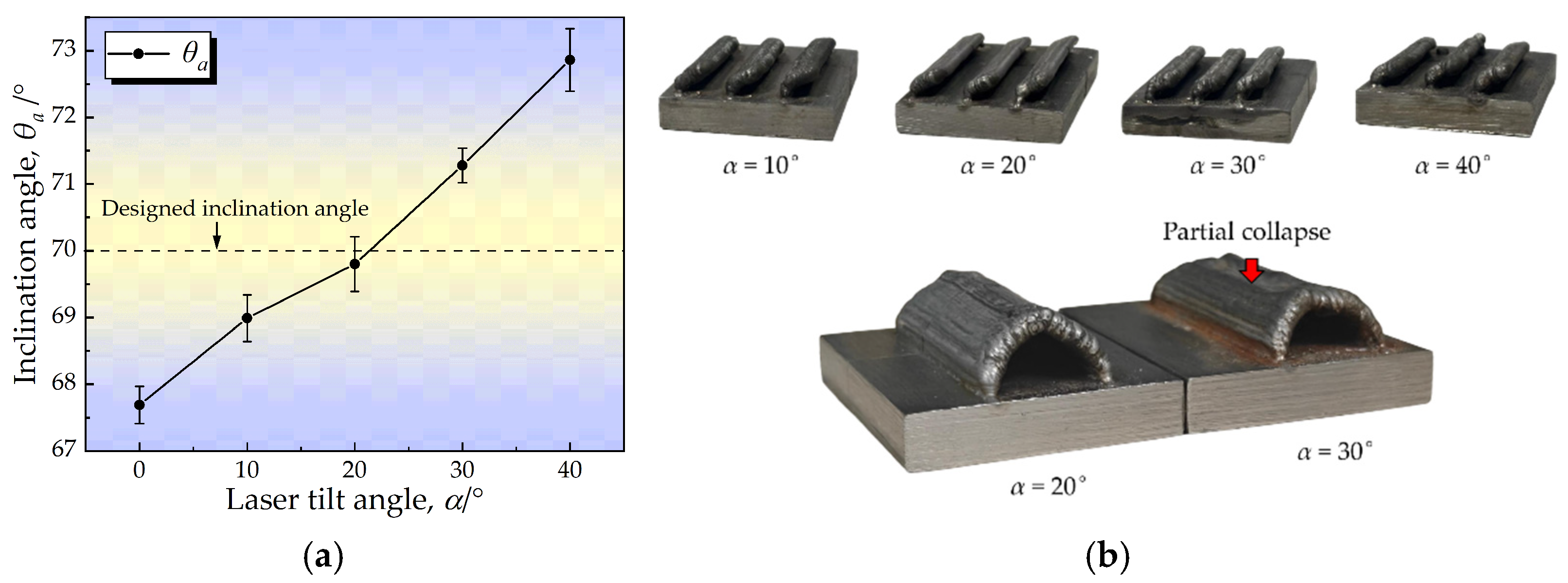

3.2. Maximum Achievable Inclination Angle

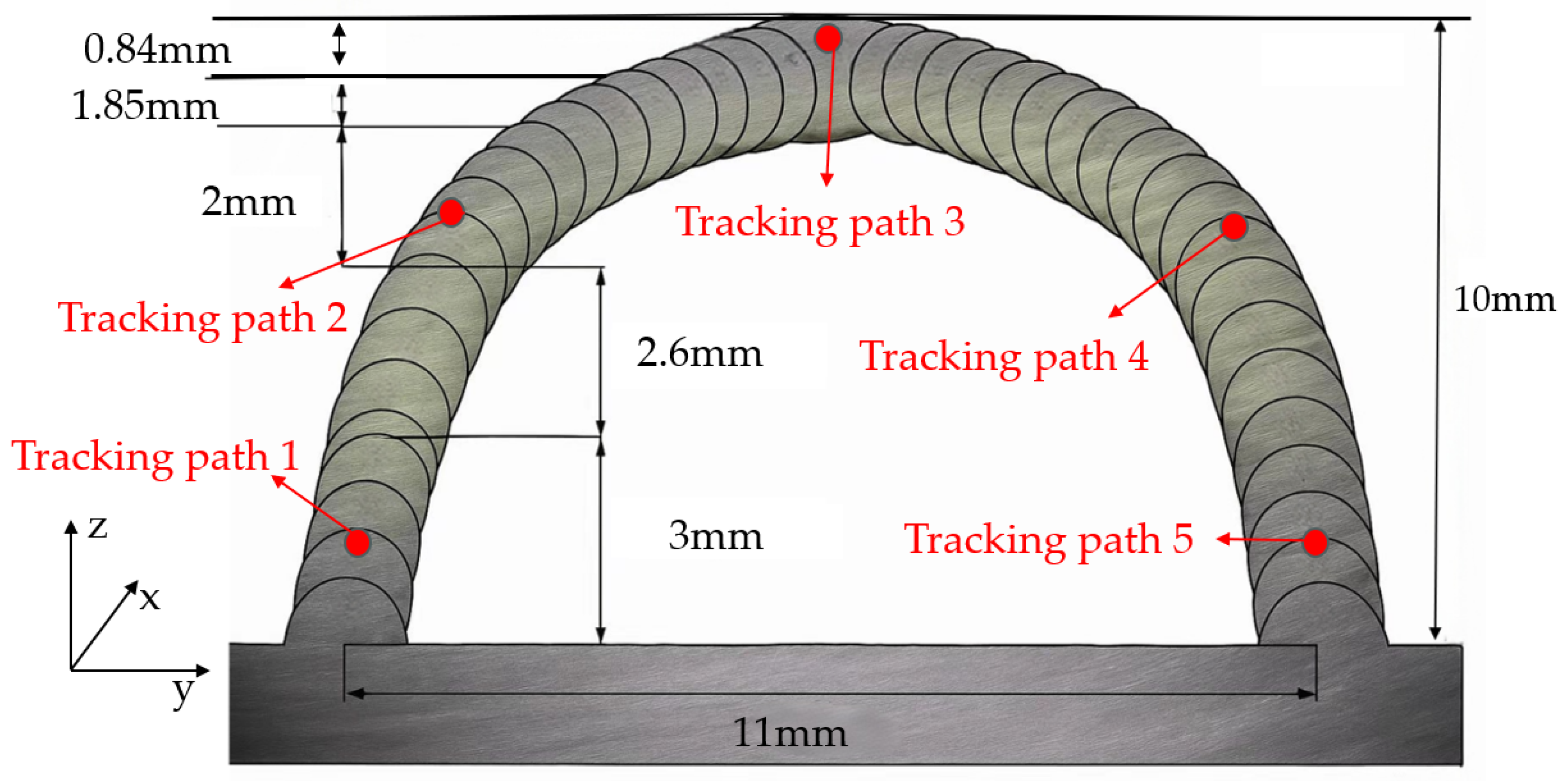

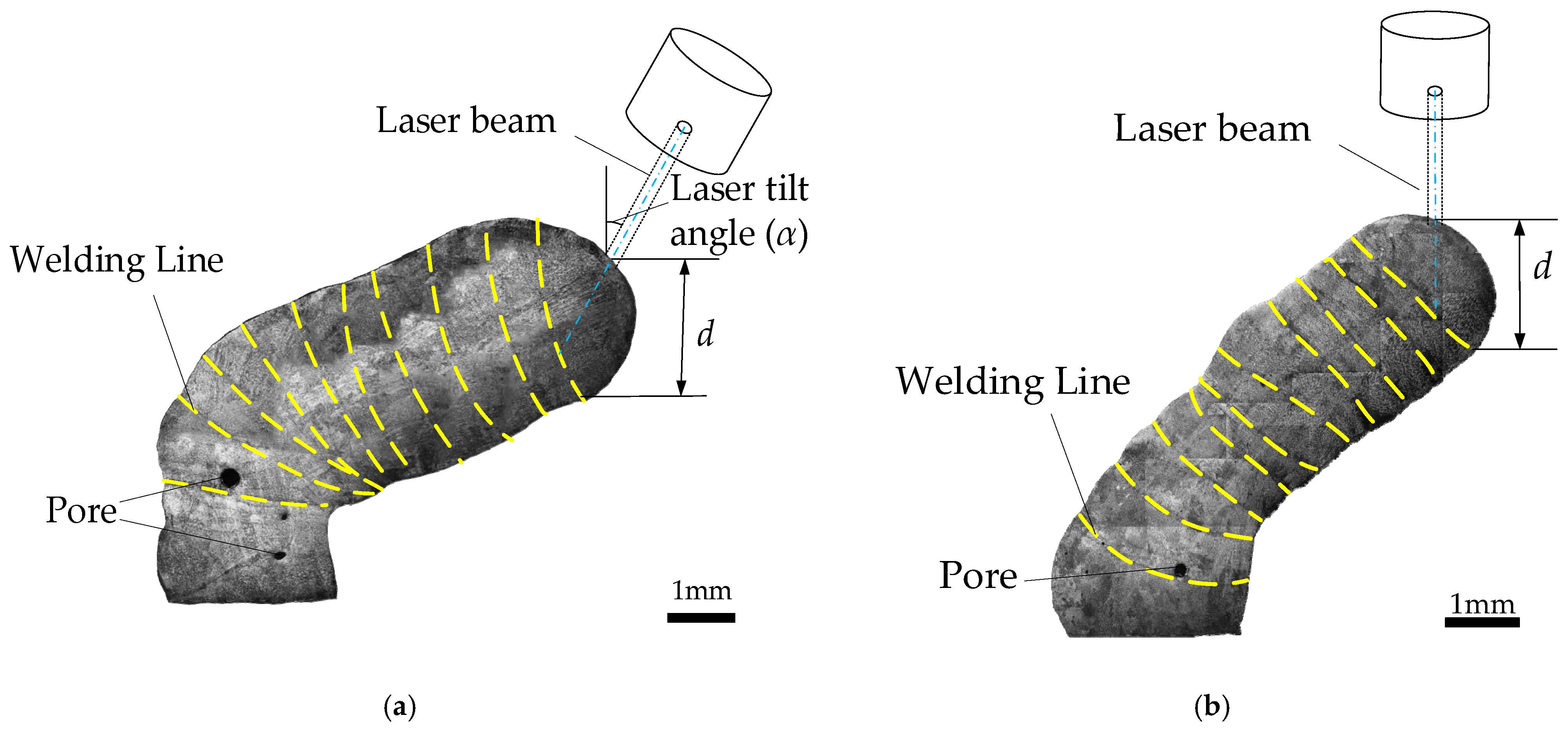

3.3. Multi-Inclination Arch Bridge Fabrication

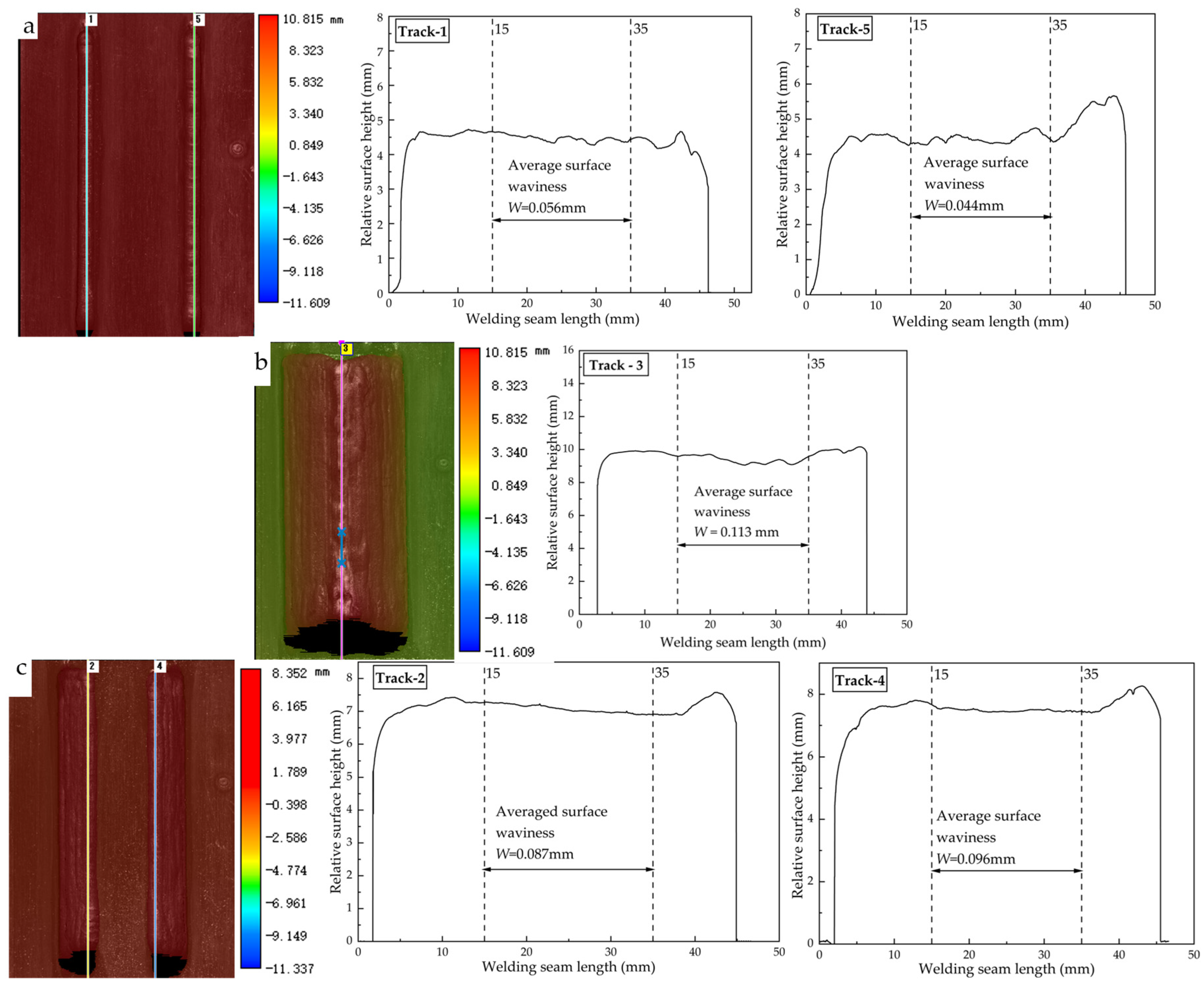

3.4. Stability and Defect Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanism of Energy Redistribution

4.2. Comparison with Conventional Strategies

4.3. Application Significance

5. Conclusions

- By introducing laser tilt angles of 0°, 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40°, the process stability and geometric quality of inclined walls were systematically evaluated. The optimal performance was achieved at a tilt angle of 20°, where the maximum achievable inclination angle reached 70° without structural collapse, thereby enabling the direct fabrication of components with steep overhangs, such as lightweight aerospace ducts and integral mounting brackets.

- Under 20° tilt, the fabricated structures exhibited reduced height fluctuation (from ±0.21 mm at 0° to ±0.09 mm at 20°) and improved wall thickness uniformity. These improvements are attributed to the energy redistribution within the melt pool, which lowered the laser-material interaction point and stabilized the molten metal flow, ensuring the dimensional accuracy required for the direct manufacturing of complex, unsupported structural elements in the automotive and energy sectors.

- The feasibility of fabricating unsupported multi-inclination components was demonstrated through the construction of a freeform arch bridge structure. The inclined paths were successfully deposited without collapse or support, validating the proposed method’s effectiveness in complex overhang geometries, and showcasing its direct application potential in creating support-free, weight-critical architectural elements and custom industrial fixtures.

- Compared with conventional formability enhancement strategies—such as parameter tuning, modified wire feeding, and support structures—the tilted laser approach is hardware-free, easier to implement, and provides intrinsic melt pool control. This enables more consistent fabrication of lightweight, geometrically complex parts with reduced trial-and-error and post-processing effort, offering a streamlined and cost-effective solution for building complex prototypes and end-use parts with internal channels or variable cross-sections in small to medium batch production.

- Looking ahead, the proposed tilted laser strategy presents strong potential for enabling the direct fabrication of unsupported, high-inclination structures such as overhangs, lattice struts, internal ducts, and bionic ribbed walls. These capabilities are especially valuable in aerospace, marine, and energy applications where geometric freedom and structural reliability are critical. Future work will focus on correlating tilt-angle-dependent thermal behavior with microstructure and mechanical performance to establish a robust process–structure–property relationship.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, C. Laser welding and additive manufacturing: A review. J. Laser Appl. 2017, 29, 062301. [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy, T.; Mukherjee, T.; Milewski, J.O.; Elmer, J.W.; Ribic, B.; Blecher, J.J.; Zhang, W. Laser powder bed fusion: A review on the influence of process parameters on the quality of the metal parts. J. Laser Appl. 2019, 31, 031101. [Google Scholar]

- Abuabiah, M.; Mbodj, N.G.; Shaqour, B.; Herzallah, L.; Juaidi, A.; Abdallah, R.; Plapper, P. Advancements in Laser Wire-Feed Metal Additive Manufacturing. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 10004454. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, B.T.; de Campos, A.A.; Casati, R.; Gonçalves, A.; Leite, M.; Ribeiro, I. Technological capabilities and sustainability aspects of metal additive manufacturing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 1737–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priarone, A.; Ingarao, M. Environmental and economic assessment of additive manufacturing in the automotive industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 976–987. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Williams, S.; Ding, J.; Dirisu, M.; Colegrove, P.; Rashid, M. The effect of torch position on the geometry of unsupported structures in wire and arc additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Lee, Y. Performance and sealing capability of nuclear pressurizer safety valves under high temperature and high pressure conditions. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2021, 384, 111491. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, P.; Wu, S. Micro-laser cladding repairing of thin-walled bronze welded part. Dev. Appl. Mater. 2024, 39, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Dinovitzer, M.; Chen, X.; Laliberte, J.; Huang, A.; Frei, J. Effect of Wire Feed Orientation on Process Stability in Laser Wire-Based Directed Energy Deposition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Additive Manufacturing and Advanced Materials Processing, Singapore, 15–18 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Ren, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Liang, B.; Li, Y. Effect of wire feeding orientation on forming accuracy and mechanical properties of structures fabricated by laser-directed energy deposition. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 85, 506–517. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Xu, X.; Stringer, J. Support Structures for Additive Manufacturing: A Review. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2018, 2, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi-Hafshejani, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Laser incidence angle influence on energy density and melt pool geometry in laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 300, 117383. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, A.; Diourté, A.; Bordreuil, C.; Bugarin, F.; Segonds, S. Thermal Scalar Field for Continuous three-dimensional Toolpath strategy using Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing for free-form thin parts. Comput.-Aided Des. 2022, 151, 103337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo, G.; Iuliano, L. Investigation of dimensional and geometrical tolerances of laser powder directed energy deposition process. Precis. Eng. 2023, 85, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chechik, L.; Schwarzkopf, K.; Rothfelder, R.; Grünewald, J.; Schmidt, M. Material dependent influence of ring/spot beam profiles in laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 9, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, I.; Pujana, J.; Lamikiz, A.; Madarieta, M.; Leunda, J. Structured light-based height control for laser metal deposition. J. Manuf. Process. 2019, 42, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanadi, N.; Pasebani, S. A Review on Wire-Laser Directed Energy Deposition: Parameter Control, Process Stability, and Future Research Paths. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, O.; Adapa, V.S.; Kersten, S.; Vaughan, D.; Masuo, C.J.; Kim, M.J.; Feldhausen, T.; Saldaña, C.; Kurfess, T.R. Effects of lead and lean in multi-axis directed energy deposition. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 5119–5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradl, P.; Cervone, A.; Colonna, P. Influence of Build Angles on Thin-Wall Geometry and Surface Texture in Laser Powder Directed Energy Deposition. Mater. Des. 2023, 234, 112352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaji, F.; Arackal Narayanan, J.; Zimny, M.; Frikel, G.; Tam, K.; Toyserkani, E. Process Planning for Additive Manufacturing of Geometries with Variable Overhang Angles Using a Robotic Laser Directed Energy Deposition System. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2022, 2, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evjemo, L.D.; Fagerholt, E.; Akselsen, O.M. Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing of Structures with Overhang. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, M.; Raza, A.; Guk, S.; Prashanth, K.G. Processability and Microstructural Evolution of ER-316L Stainless Steel by Laser-Directed Energy Deposition. Metals 2021, 11, 1865. [Google Scholar]

- Dinovitzer, M.; Chen, X.; Laliberte, J.; Huang, X.; Frei, H. Effect of Wire and Laser Feed Orientation on Relative Deposition Efficiency in Laser Wire-Based Directed Energy Deposition. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102150. [Google Scholar]

- Scipioni Bertoli, U.; Guss, G.; Wu, S.; Matthews, M.J.; Schoenung, J.M. In-situ characterization of laser-powder in-teraction and cooling rates through high-speed imaging of powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2017, 135, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, C.; Mi, G.; Zhang, X. Effects of laser oscillating frequency on energy distribution, molten pool morphology, and grain structure of laser additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 10, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Jinoop, A.N.; Kumar, G.T.A.; Palani, I.A.; Paul, C.P.; Prashanth, K.G. Effect of interlayer delay on the microstructure and mechanical properties of wire arc additive manufactured wall structures. Materials 2021, 14, 4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, Z.; Ren, Z.; Shi, Y.; Fan, D. Effect of wire feeding mode on additive forming precision of double-pulsed TIG process with stepped filling wire. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2022, 43, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, N.; Giorgetti, A.; Palladino, M.; Giovannetti, I.; Arcidiacono, G.; Citti, P. Study on the effect of inter-layer cooling time on porosity and melt pool in Inconel 718 components processed by laser powder bed fusion. Materials 2023, 16, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyence Corporation. LJ-X8000A Development Version Product Catalog; Keyence: Osaka, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Triantaphyllou, A.; Giusca, C.L.; Macaulay, G.D.; Roerig, F.; Hoebel, M.; Leach, R.K.; Tomita, B.; Milne, K.A. An investigation into the side surface roughness of parts fabricated by selective laser melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 96, 3955–3964. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Sattari, M.; Babu, A.; Sood, A.; Römer, G.-W.; Hermans, M. Revealing the effects of laser beam shaping on melt pool behaviour in conduction-mode laser melting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 3955–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.H.; Wong, W.L.E.; Dalgarno, K.W. An overview of powder granulometry on feedstock and part performance in the selective laser melting process. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 18, 228–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, M.; Saeed, A.; Mohammadi, A. A comprehensive study on meltpool depth in laser-based powder bed fusion of Inconel 718. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 113, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; de Damborenea, J.A.; Sánchez-Herencia, A.J.; Ruiz-Navas, E.M.; Gordo, E. An experimental and numeri-cal study of microstructural evolution in wire and arc additively manufactured Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 651, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Williams, S.W.; Xiao, M. In-situ observation and investigation of the interlayer bonding mechanism in wire-arc additive manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 291, 117032. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Shi, L.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L. Process optimization and microstructure analysis of laser wire addi-tive manufacturing for 316L stainless steel thin-walled components. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 315, 117895. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q. Effect of interlayer cooling strategy on residual stress and distortion in laser metal deposition of inclined structures. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 79, 103845. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K.L.; Brown, M.S.; Wilson, T.G. Real-time monitoring and control of layer thickness variation in multi-axis laser directed energy deposition systems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 2457–2472. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Bai, Q. Defect formation mechanisms in selective laser melting: A review. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2017, 30, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juaidi, A.M.S. Advancements in Laser Wire-Feed Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Brief Review. Materials 2023, 16, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y. Laser Wire Additive Manufacturing of High-Aspect-Ratio Inclined Thin Walls Using Ti–6Al–4V Wire. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 128, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Park, S.Y.; Choi, H. Effects of Substrate Inclination on Molten Pool Geometry in Laser Metal Deposition Using 304 Stainless Steel. J. Laser Appl. 2025, 37, 012009. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, M.; Reutzel, E.W.; Martukanitz, R.P. Design Guidelines for Thin-Walled Structures Using Laser Metal Deposition. In Proceedings of the 37th International Congress on Applications of Lasers and Electro-Optics (ICALEO), Orlando, FL, USA, 14–18 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Substrate | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Ni | Cr | N | Mo | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 316 | 0.043 | 0.46 | 1.12 | 0.027 | 0.003 | 10.01 | 18.15 | 0.031 | 2.1 | Allowance |

| Welding Wire | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Ni | Cr | Mo | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 316L | 0.03 | 0.3~0.65 | 1~2.5 | 0.03 | 003 | 11~14 | 18~20 | 2~3 | 0.75 |

| Laser Tilt Angle, (°) | Laser Power, (W) | Scanning Speed, (mm/s) | Wire Feeding Speed, (mm/s) | Shielding GAS flow Rate, (L/min) | Linear Energy Density, (J/mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 540 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 15 | 180 |

| 10 | 540 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 15 | 180 |

| 20 | 540 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 15 | 180 |

| 30 | 540 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 15 | 180 |

| 40 | 540 | 3.0 | 10.0 | 15 | 180 |

| (°) | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section contour |  |  |  |  |  |

| Tracking path | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Averaged |

| Waviness (mm) | 0.056 | 0.087 | 0.113 | 0.096 | 0.044 | 0.079 |

| No. | Material | Wire Diameter | Wall Width | Laser Tilt Angle | Max Achievable Inclination | Surface Quality | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 316L Stainless Steel | Ø 1.2 mm | ~2–3 mm | 0°, 10°, 20°, 30°, and 40° | 70° | W ≈ 0.12 mm | This study |

| 2 | Ti–6Al–4V | Ø 0.3 mm | ~0.6–1.0 mm | 0° | 69° | Not reported | [42] |

| 3 | 304 Stainless Steel | Ø 1.2 mm | Not reported | 0–40° (Substrate tilt) | 40° | Not reported | [43] |

| 4 | Ti–6Al–4V | Not reported | Not reported | 0° | 30° | Not reported | [44] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, G.; Qiao, J.; Ding, Q.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, P.; Liu, H.; Wu, Z.; Han, H. Enhancing Formability of High-Inclination Thin-Walled and Arch Bridge Structures via Tilted Laser Wire Additive Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12675. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312675

Li G, Qiao J, Ding Q, Li P, Li Z, Zhang P, Liu H, Wu Z, Han H. Enhancing Formability of High-Inclination Thin-Walled and Arch Bridge Structures via Tilted Laser Wire Additive Manufacturing. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12675. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312675

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Genfei, Junjie Qiao, Qiangwei Ding, Peiyue Li, Zhiqiang Li, Peng Zhang, He Liu, Zhihao Wu, and Hongbiao Han. 2025. "Enhancing Formability of High-Inclination Thin-Walled and Arch Bridge Structures via Tilted Laser Wire Additive Manufacturing" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12675. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312675

APA StyleLi, G., Qiao, J., Ding, Q., Li, P., Li, Z., Zhang, P., Liu, H., Wu, Z., & Han, H. (2025). Enhancing Formability of High-Inclination Thin-Walled and Arch Bridge Structures via Tilted Laser Wire Additive Manufacturing. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12675. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312675