3.3.1. Carotenoids

The carotenoid content of rowan fruit varies depending on the variety, as well as the location and growing conditions. According to Zymone et al. [

30], carotenoid concentrations varied by several dozen times across the analyzed rowanberry cultivars. In the present study, the raw fruit contained 2818.98 mg/100 g d.m. (

Table 1). It should be noted, however, that the nectars were prepared by diluting the pulp with water in a 1:1 ratio, which inherently reduces the measurable concentration of carotenoids in the final product. After processing, the total carotenoid content in the nectars ranged from 24.74 to 490.41 mg/100 mL (

Table 3), values that reflect both the dilution effect and the efficiency of carotenoid release into the aqueous matrix. The carotenoid profile of the nectars was dominated by lutein derivatives (LD) and total carotenes (TC). Trace amounts of xanthophylls (TX) were detected in several freshly prepared samples but fell below the detection limit after storage.

To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have reported the effect of sweetener addition on carotenoid content in fruit juices or nectars. However, significant differences were observed among the tested variants in the present study.

In nectars prepared from fresh pulp (F), the highest initial carotenoid contents were found in the unsweetened (1F), steviol glycosides-sweetened (5F), and with added erythritol (4F) variants, with values of 303.59, 244.33, and 240.41 mg/100 mL, respectively. Among the nectars tested, variant 1F showed the largest increase in carotenoid content, a 61% increase, during refrigerated storage after three months (3m 4). A similar trend was observed in variant 4F, with a 33% increase under the same conditions. Storage at 30 °C led to stabilization or significant decreases, as in the case of 5F, where total carotenoid content decreased by 13%. A similar pattern was observed in nectars made from steamed pulp (S). In these samples, the 4S and 1S variants showed a significant increase in carotenoid content after refrigerated storage, reaching 69% and 130% increases, respectively, after three months. However, during storage at 30 °C, carotenoid levels decreased significantly compared to the 3m 4 samples, with losses ranging from 35% to 40% depending on the variant.

In the unsweetened variants (1), higher TCD values were consistently observed in nectars prepared with fresh fruit pulp (F) at all time points, indicating that steaming the pulp reduced the measurable total carotenoid content in this formulation or promoted transformations (isomerization or oxidation) that lowered the detectable fraction of total trans-carotenoids. In contrast, in nectars sweetened with sucrose (2), an increase in carotenoid content was observed following steaming (difference (Δ) of 117.8 mg/100 mL), but this advantage largely disappeared after 3 months of refrigerated storage (Δ = +11.9) and reversed at 30 °C (Δ = −15.5), suggesting dynamic interactions between sucrose, processing, and temperature that influence both carotenoid extraction and stability during storage. Samples sweetened with xylitol prepared from steamed rowanberry pulp (3S) retained more carotenoids than their fresh counterparts (3F) throughout the study period. The advantage of steaming was greatest immediately after processing and partially decreased during storage, suggesting that fruit steaming and the addition of xylitol to the nectar promote initial carotenoid extraction or protection, but some degradation or redistribution occurs over time. Erythritol-sweetened samples (4) exhibited a temperature-dependent behavior: a moderate advantage of steaming at the beginning (Δ = +22.5), a pronounced advantage after refrigerated storage (Δ = +124.1), but a reversal of this trend at elevated temperature (Δ = −14.5). This indicates that the addition of erythritol, in combination with fruit pulp steaming, can strongly stabilize carotenoids under refrigerated conditions, while higher temperatures accelerate degradation processes that offset this benefit. Steviol glycosides-sweetened nectars (5) initially showed higher TC values in fresh samples (Δ = +76.3 for 0 m), but this advantage was lost during storage (Δ ≈ +13 and +6 for 3m 4 and 3m 30, respectively), suggesting that steaming promotes slow release or better retention of carotenoids in steviol glycosides preparations over time.

The susceptibility of carotenoids to degradation depends on several factors, including their chemical structure, the type of matrix, light exposure, temperature, water activity, and antioxidant content in food products [

31]. In rowanberry nectars, storage-related variability in carotenoid content may result from intramolecular transformations and quantitative changes between individual carotenoid groups or isomers. Observed changes over time, reversals, or decreases in differences in carotenoid content indicate ongoing alterations in the composition of pigments during storage, possibly due to degradation or other factors. For example, variants prepared from steamed pulp, which initially contained higher carotenoid levels, tended to lose this advantage at 30 °C, consistent with accelerated thermal or oxidative degradation at elevated temperatures. Refrigerated storage was associated with increases in measured carotenoid content, presumably caused by pigment release, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear and require further investigation.

This phenomenon was described by Tang and Chen [

32], who analyzed the effect of time, temperature, and light exposure on the stability of carotenoid pigments in freeze-dried carrot extract. Their study indicated a significant relationship between the chemical structure of carotenoids and the direction and intensity of their transformations during storage. They found that the amount of all-trans-carotenoids in the freeze-dried product decreased with increasing temperature or exposure time. In samples stored in the dark, 13-

cis carotenoid isomers predominated, while light exposure favored the synthesis of 9-

cis compounds.

Di-

cis isomers, such as 13,15-

di-

cis-β-carotene, were formed during high-temperature storage of extracts. Nowacka et al. [

33] studied the effect of storage time and temperature on carotenoid content in dried carrots. These researchers found that carotenoids in dried carrots degraded more rapidly at higher temperatures (25 and 40 °C), at which the reaction rate constant was approximately twice as high as at the lower storage temperature (4 °C).

It is worth noting that steaming the fruit pulp in most cases (nectars with sucrose, erythritol, xylitol) increased the release of carotenoids. This processing effect is consistent with previous research on fruit beverages. Dorothy et al. [

34] cooked or steamed marula fruits before juicing them. Their studies showed that both forms of thermal processing had a positive effect on the total carotene content in marula juice compared to the control sample. The authors confirm that this treatment softens the fruit matrix, facilitating extraction and increasing the degree to which carotenes are released into the juice (increasing their extractability). It is worth noting that a higher carotene concentration was noted in the steamed sample compared to the boiled sample. This may be due to the steam’s ability to penetrate cellular and fiber structures, increasing the carotene concentration in the extracted juice. Steaming may also help break down carotenoid-protein complexes, increasing the amount of carotenoids in the juice.

The MANOVA results (

Table A2) demonstrate that total carotenoid content in rowanberry nectars was significantly influenced by sweetener type, fruit preparation, and storage conditions (

p < 0.05). Sweetener type had the largest effect, followed by storage and preparation, indicating that formulation and processing strongly determine carotenoid levels. All interaction terms, including sweetener × preparation, sweetener × storage, preparation × storage, and the three-way interaction, were significant, showing that the effects of individual factors are interdependent. These findings highlight the complex, context-dependent nature of carotenoid retention in rowanberry nectars and underscore the importance of considering combined effects of formulation, processing, and storage.

3.3.2. Flavonols

In the rowanberry nectars, the presence of quercetin and isorhamnetin glycosides was confirmed, with quercetin-3-O-rutinoside being the predominant flavonol in all samples (

Table 4). Statistical analysis demonstrated that the content of the analyzed compounds was determined by several factors, including the method of pulp preparation applied in nectar production, the type of sweetening agent used, storage conditions, as well as interactions among these variables (

Table A3).

The results clearly indicate that steaming of the fruit pulp had a beneficial effect on the flavonol content by enhancing their extraction from the plant matrix. In nectars produced from steamed pulp (S), the flavonol concentration was 4–8 times higher than in the samples prepared without this process. Interestingly, the addition of sweetening agents also exerted a favorable influence, and a synergistic effect between steaming and sweetener addition was evident. Within the group of nectars obtained from steamed pulp (S), the total flavonol content in the unsweetened sample (1S 0m) was more than fourfold higher compared to the nectar made from unsteamed pulp (1F 0m). In samples containing sweeteners, the levels of the analyzed compounds were 6–8 times higher than in their counterparts derived from unheated pulp. This effect was most pronounced in the nectar sweetened with steviol glycosides (5S 0m), where the flavonol concentration reached 8.76 mg/100 mL. For comparison, the corresponding product from unsteamed pulp (5F 0m) contained only 1.08 mg F/100 mL. Overall, all sweetened nectars (including those with sucrose, xylitol, and erythritol) prepared from steamed pulp exhibited significantly higher flavonol contents than the unsweetened sample (1S 0m).

Significant alterations in flavonol content were observed in all products during storage. In nectars prepared from unsteamed pulp (F), a general decrease in flavonol concentration was observed, with a higher degradation rate at 30 °C compared to refrigerated storage conditions (

Table 4). The inclusion of sweetening agents in the formulation effectively reduced the rate of degradation. For instance, in the unsweetened nectar (1F), the polyphenol content decreased by 23% after three months of storage at 4 °C. In contrast, in sweetened variants, the reduction ranged from 5 to 8% (e.g., 3F 3m 4 with xylitol and 4F 3m 4 with erythritol). In the nectar containing steviol glycosides (5F), flavonols were the most stable, with their concentration remaining practically unchanged under refrigerated storage.

In nectars produced from steamed pulp (S), the effect of storage on flavonol content was less consistent. In nectars sweetened with xylitol (3S) and steviol glycosides (5S), the levels of the analyzed compounds were lower compared to fresh samples, regardless of storage temperature. Nevertheless, the extent of flavonol degradation was substantially greater at 30 °C than at 4 °C. In contrast, in unsweetened nectar (1S) and those containing sucrose (2S) or erythritol (4S) stored under refrigeration, an increase of 11–14% in flavonol content was observed. Conversely, storage at elevated temperature led to a decrease ranging from 5% (1S, 2S) to 17% (4S).

Steaming softens the cell walls of fruit, enhancing the release of phenolic compounds, including flavonols, into juices and purees. Studies on marula fruit have shown that steaming before juice extraction significantly increases the total phenolic content and antioxidant activity compared to un-steamed (control) samples. Boiling also increases phenolic content, but steaming is superior, as it avoids direct contact with water and better preserves bioactive compounds [

34]. Juices from steamed pomegranate fruits had the highest phenolic recoveries, including flavonols, compared to juices from untreated or peeled fruits. Additional juice treatments (like filtration) reduced phenolic content, but steaming alone maximized recovery [

35].

3.3.3. Flavan-3-Ols

The profile and content of flavan-3-ols in rowan nectars are presented in

Table 5 and

Table A4. Unsweetened nectar obtained from unsteamed fruit pulp contained (in total) more of the tested compounds (1F 0m; 19.80 mg/100 mL) than nectar from steamed pulp (1S 0m; 13.65 mg/100 mL). Except for procyanidin A2 and B1, whose concentrations slightly increased as a result of the thermal process, degradation of flavan-3-ols was common in the steamed sample. The effect of storage temperature on TF-ols was different for both samples. While a decrease in the concentration of the tested compounds was observed after 3 months in the 1F nectar (higher losses at 30 °C), the total flavan-3-ol content increased in the 1S nectar, with more of the tested compounds detected in the sample stored at higher temperatures. Generally, fewer polyphenols were detected in the samples containing added sweeteners than in the unsweetened samples. In nectars with polyols—xylitol (3) and erythritol (4)—both obtained from parboiled and unsteamed pulp—fewer flavan-3-ols were detected than in the products with sucrose and steviol glycosides. A common phenomenon observed in the tested nectars, particularly those steamed, was a significant increase in the percentage of flavan-3-ols in the samples stored at 30 °C.

In some fruits, steam or heat treatment can increase flavanol content or their extractability. For example, heating medlar fruit at 60 °C led to the highest flavanol content, likely due to enzyme inactivation (polyphenol oxidase) and improved release from cell structures [

36]. Similarly, steaming chestnut fruit preserves or enhances flavonoid levels [

37]. Steam explosion in citrus and sumac fruits also improved the recovery of certain flavanols and flavonoids [

38,

39,

40]. In other cases, especially at higher temperatures or with prolonged heating, flavanol content decreases. For instance, drying honeysuckle berries at 75 °C resulted in a reduction of over 70% in flavanols [

41]. Superheated steam treatment of

Baccaurea pubera fruit reduced total flavonoid content by 16.5% [

42]. Flavanol losses after processing were also observed in strawberries and apples, depending on the method and fruit part used [

43].

Heat can inactivate or, if insufficient, leave active enzymes like polyphenol oxidase (PPO) and peroxidase (POD), which catalyze oxidative degradation of flavanols. Incomplete inactivation during mild heat treatment can lead to significant flavanol loss, while higher temperatures that fully inactivate these enzymes can help preserve or even increase flavanol content by preventing enzymatic breakdown [

36,

43,

44,

45]. Heat disrupts cell walls and membranes, releasing bound flavanols and increasing their extractability. This can result in higher measured flavanol content, especially when heat is applied to whole fruits or peels rich in these compounds [

36,

43,

46]. Generally, flavanols are sensitive to high temperatures, with degradation rates increasing with temperature. Structural features, such as the presence of double bonds and glycosylation, influence thermal stability—glycosylated flavonoids are generally more heat-resistant [

41,

47,

48].

Different sweeteners (sucrose, stevia, fructose, xylitol, erythritol, honey, jaggery, date syrup) can affect the stability and degradation rate of flavanols and other polyphenols during processing and storage. For example, in citrus–maqui beverages, stevia resulted in a higher loss of flavanones under light and room temperature conditions compared to sucrose. However, under refrigeration or darkness, both sweeteners exhibited similar losses [

49]. In blackberry jams, xylitol slowed anthocyanin degradation, while fructose accelerated it; sucrose-containing jams had lower polyphenol content than those with fructose or xylitol [

50]. The impact of sweeteners is often modulated by storage temperature, light exposure, and duration. Higher temperatures and light can accelerate flavanol degradation, especially with certain sweeteners [

49,

50].

3.3.4. Polymeric Procyanidins

Polymeric procyanidins (PPCs) constitute a significant group of polyphenolic compounds present in rowanberries (

Sorbus aucuparia L.). Rutkowska et al. [

51] determined the total content of procyanidins, expressed as cyanidin chloride equivalents (CyE), determined by the n-butanol/HCl method in defatted acetone-water extract (1:1,

v/

v), at 1.702 g/100 g dm. The raw material used in the present study contained 8.147 g/100 g d.m. of procyanidins (

Table 1). As the nectars were produced from pulp diluted with water, the concentrations measured in the final products were inherently lower, ranging from 0.772 to 1.767 g/100 mL depending on the sweetener type, fruit treatment, and storage conditions (

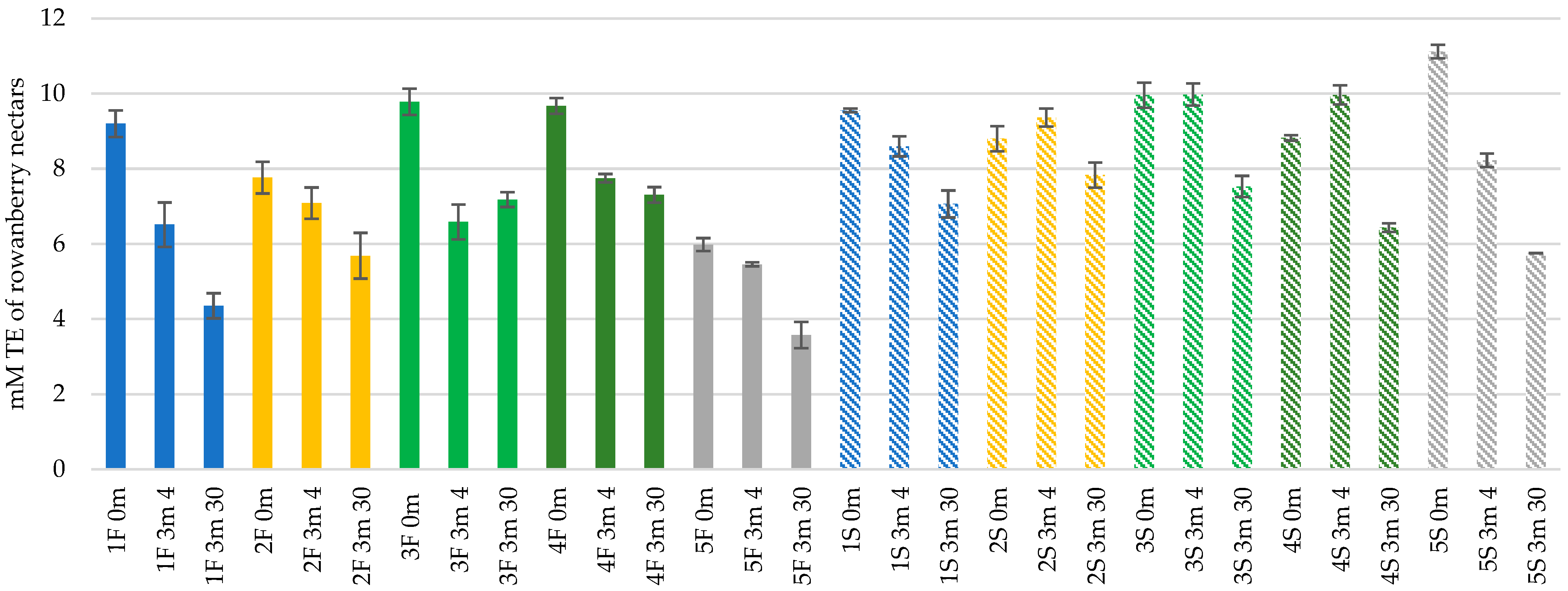

Figure 3).

In all cases, nectars prepared from steamed fruit pulp (S) contained higher levels of PPC than those from fresh fruit pulp (F), suggesting that thermal treatment promoted the release of bound procyanidins from the cell–matrix. Similar observations were made by Kessy et al. [

52], who analyzed the effect of different processing methods on the phenolic compound content and antioxidant activity in pericarp litchi. They found that the combination of steam blanching and drying at 60 °C significantly improved the release of phenolic compounds, including procyanidins, compared to drying alone, which caused significant losses. The positive effect of steam blanching on procyanidins is primarily explained by the inactivation of highly active endogenous enzymes characteristic of fresh plant materials, such as polyphenoloxidase and peroxidase. Inactivation of these enzymes prevents the degradation of phenolic compounds, including procyanidins, by inhibiting the catalysis of their oxidation. A second mechanism explaining the positive effect of blanching on procyanidin extraction is the physical change in the structure of the lychee pericarp during heat treatment, which facilitates the recovery of procyanidins bound to the cell–matrix, a phenomenon known as enhanced release of bound procyanidins.

At the initial stage (0 m), PPC levels in S nectars were on average 25–40% higher than in the corresponding F samples (

Figure 3).

After three months of refrigerated storage (3m 4), the differences became more pronounced in most sweetened variants. The most significant increase was observed for samples sweetened with erythritol and steviol glycosides, representing up to 60–70% higher PPC content than their fresh-pulp counterparts. This suggests a protective effect of specific sweeteners, particularly erythritol and steviol glycosides.

Storage at 30 °C (3m 30) led to a general decline in PPC content in all samples, though S variants consistently retained 20–50% more PPCs than F ones, confirming that heat treatment improved the long-term stability of polymeric procyanidins. The effect was particularly evident in the sucrose (2S 3m 30 = 1.30 g/100 mL vs. 2F 3m 30 = 0.77 g/100 mL) and steviol glycosides (5S 3m 30 = 1.65 g/100 mL vs. 5F 3m 30 = 1.04 g/100 mL) variants.

Polymeric flavan-3-ols in rowan nectars consist mainly of (+)-catechin as the predominant constitutive unit of procyanidins. The mean degree of polymerization (mDP), reflecting the average number of flavan-3-ol units in procyanidin chains released during acid-catalyzed depolymerization, is a key parameter determining their bioavailability and bioactivity. In the present study, the mDP of the polymeric fraction ranged from 1.90 to 1.99. Such values are considerably lower than those reported for intact, native procyanidins, which typically exhibit mDP values exceeding 5. Some studies show that the molecular size plays a major role in determining the bioavailability of PPCs, which is 5–50% compared to the corresponding flavan-3-ol monomers. Furthermore, oligomeric PPCs are absorbed more slowly than monomeric flavan-3-ols [

53]. According to the study by Hellström et al. [

54], highly polymerized forms of procyanidins predominate in rowan fruit (248 mg/100 g of average, DP > 10), and the content of extractable and non-extractable procyanidins is 273 and 158 mg/100 g of average (DP = 20.8), respectively. In the analyzed nectars, a significant decrease in the degree of procyanidin polymerization was observed compared to the literature data for the raw material [

54]. This could be due to the dilution of the juice with water or to differences resulting from the genotypic characteristics of the fruit; however, the determined DP of the procyanidins in the raw material was also only 1.92. The obtained results could therefore be, to some extent, a consequence of the intrinsic methodological limitations of the phloroglucinolysis procedure used for mDP quantification. Phloroglucinolysis depolymerizes procyanidins through nucleophilic cleavage under acidic conditions, producing terminal units (catechin/epicatechin) and phloroglucinol adducts. While this method provides a reliable estimate of average polymer length, it does not enable quantification of the size distribution of individual procyanidin fractions and is prone to side reactions such as epimerization and heterocyclic ring opening [

55]. Additionally, substantial loss of polymeric procyanidins likely occurred during fruit pressing. Procyanidin polymers strongly associate with insoluble cell wall polysaccharides, making them prone to retention in pomace. Similar results were reported in the analysis of strawberry juice production [

56]. These observations confirm the results of White et al. [

57], who described the effect of individual stages of cranberry processing on the content of procyanidin polymers, among others, in juices. These authors noted that pressing resulted in a significant reduction in the content of polymeric procyanidins due to the separation of skins and seeds. The remaining content in the pomace was 43–52% polymeric procyanidins, 22–31% oligomeric compounds, and approximately 40% of the total procyanidins. This suggests that lower oligomers are more readily absorbed into the juice than polymerized forms of PPC [

57]. According to Howard et al. [

58], the greater retention of monomers and dimers during processing indicates that low molecular weight procyanidins bind less strongly to polysaccharides, cell wall proteins, or are more resistant to thermal degradation.

The MANOVA results (

Table A5) indicate that all analyzed factors had a statistically significant effect (

p < 0.001) on the polymeric procyanidin content in rowanberry nectars. Among the main factors, the sweetener type exerted the strongest individual influence (F = 81,071), which determines polymeric procyanidin levels, followed by fruit preparation (F = 36,449) and storage temperature (F = 2005), which modulate these effects through synergistic or antagonistic interactions.

Significant interaction effects were also observed between sweetener and preparation (F = 2872), sweetener and storage (F = 380), and, to a lesser extent, preparation and storage (F = 59), indicating that the impact of each sweetener on PPC retention depended both on the processing method and storage conditions. The three-way interaction (sweetener × preparation × storage) was also statistically significant (F = 241), confirming the complex, multivariate nature of PPC stability in the nectar system.

The stability of procyanidins even after long-term storage suggests that these compounds are relatively resistant to degradation and may play a significant role in their antioxidant potential.

3.3.5. Phenolic Acids

Phenolic acids were the second most abundant group of phenolic compounds, following flavan-3-ols (procyanidins, PAC), which predominated in all rowanberry nectar samples analyzed. As in the raw fruit, chlorogenic and neochlorogenic acids were the dominant phenolic acids in the nectars, whereas 1,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid occurred at substantially lower concentrations. Cryptochlorogenic and caffeic acids, which were detectable in raw fruit, were not identified in the nectars, most likely because their concentrations, after processing and dilution of the pulp, fell below the analytical detection limit (

Table 1 and

Table 6).

In the nectar prepared from fresh fruit pulp without added sweetener (1F), the highest initial concentration of phenolic acids was recorded; however, this variant also exhibited the most pronounced degradation during storage. After three months, the rowanberry nectars without sweeteners showed a 21% and 29% reduction in the content of these compounds when stored at 4 °C and 30 °C, respectively. In contrast, the nectar prepared from steamed fruit pulp without a sweetener (1S) demonstrated an increase in phenolic acid content, particularly during refrigerated storage, exhibiting a 16% rise.

Sweetened nectars prepared from fresh fruit pulp (F variants) exhibited, on average, lower phenolic acid content than those from steamed pulp (S variants). Notably, F2 and F4 samples (sweetened with sucrose and erythritol) displayed greater stability of phenolic acids during storage. In contrast, their steamed counterparts (S2 and S4) showed an increase in phenolic acid content after three months of refrigerated storage, likely due to enhanced release of bound phenolics from the fruit matrix.

Similar observations were made by Nowicka and Wojdyło [

59], who studied the effect of sweeteners on the content of polyphenolic compounds in sour cherry purees. They reported that total phenolic acid content in unsweetened cherry puree was 111.53 mg/100 g dry matter (dm), while sucrose and erythritol addition reduced it—as in our study. Furthermore, for hydroxycinnamic acids specifically, after six months of storage at 4 °C, cherry puree sweetened with sucrose and erythritol contained 81.46 mg/100 g dm and 77.93 mg/100 g dm, respectively—both higher than the initial post-processing levels (sucrose: 70.24; erythritol: 74.63 mg/100 g dm). It can be concluded that although sweetener addition was associated with lower initial phenolic content, some formulations showed reduced losses during storage. Similar observations were reported in lyophilized apple purées, where samples with 5% sucrose retained chlorogenic acid content at levels comparable to unsweetened material after six months [

60]. In the present study, regardless of the raw material processing method (fresh or steamed fruit pulp), nectars sweetened with xylitol and steviol glycosides exhibited a decline in total phenolic acids during storage. This decrease was particularly pronounced after three months at 30 °C. These results indicate that the stability of phenolic acids during storage varies among sweeteners. This suggests that the use of xylitol and steviol glycosides, despite their natural origin and favorable glycemic profiles, may contribute to a reduction in polyphenol stability, probably due to limited antioxidant or matrix-protective interactions compared to sugar alcohols like erythritol or disaccharides such as sucrose. Steviol glycosides, on the other hand, appear to have the least negative initial impact on the phenolic acid content.

Based on the MANOVA results for phenolic acid content, all examined factors and their interactions had a statistically significant effect (

p < 0.001) on the variation in phenolic acids in the rowanberry nectar samples (

Table A6). The most substantial individual influence was observed for the type of sweetener (F = 12,959.91,

p < 0.001), followed by the fruit preparation method (F = 7494.41,

p < 0.001) and storage conditions (F = 5508.79,

p < 0.001). Additionally, all interaction effects were highly significant, including the sweetener × preparation (F = 2984.14), sweetener × storage (F = 813.94), preparation × storage (F = 1804.34), and the three-way interaction sweetener × preparation × storage (F = 970.57). These results indicate that the influence of sweetener type on phenolic acid content was strongly dependent on the processing method and storage conditions, confirming the complex behavior of phenolic compounds under different formulation and storage scenarios.

It is worth noting that, in most cases, the concentration of chlorogenic acids in rowanberry fruit is higher than the levels typically found in vegetables and other commonly consumed fruits [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62].