A New Assessment Tool for Risk of Falling and Telerehabilitation in Neurological Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Ancillary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

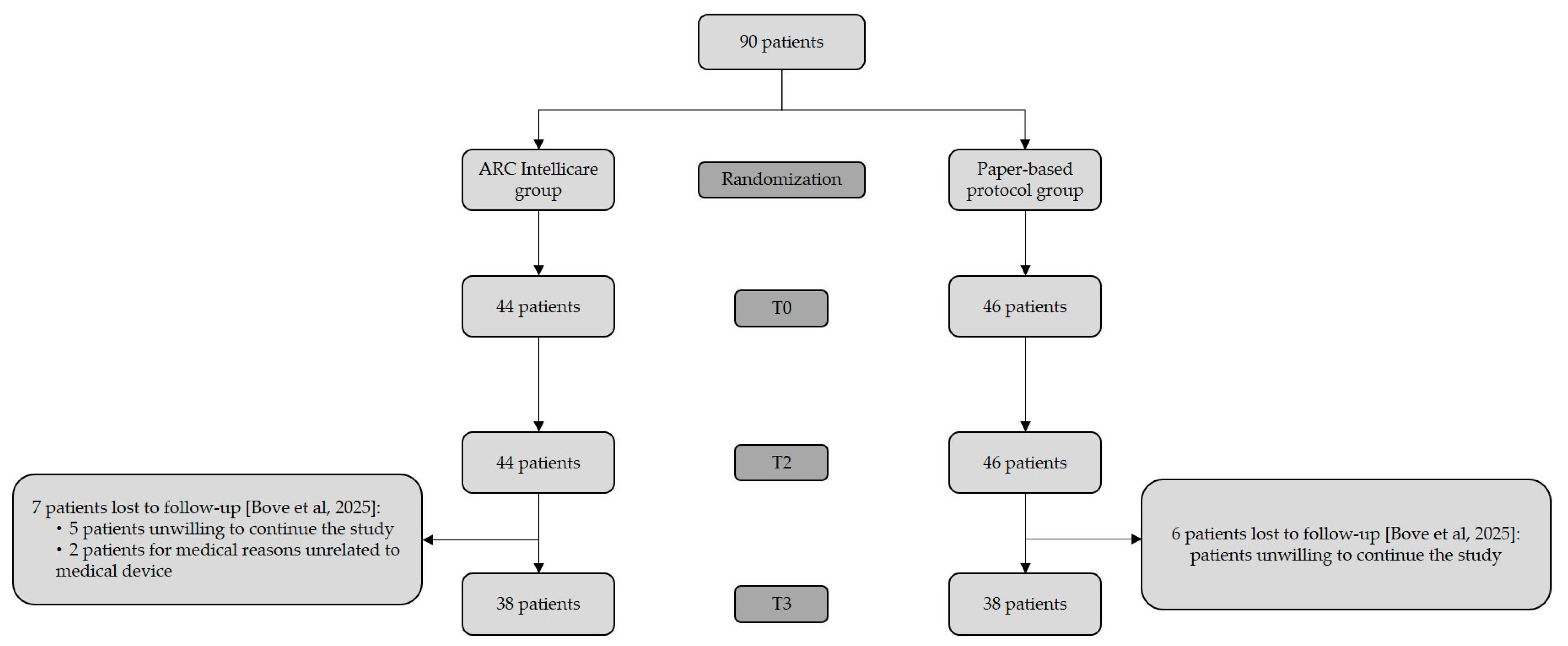

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kringle, E.; Trammell, M.; Brown, E.D. Telerehabilitation Strategies and Resources for Rehabilitation Professionals. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 2191–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, M.; Moja, L.; Banzi, R.; Pistotti, V.; Tonin, P.; Venneri, A.; Turolla, A. Telerehabilitation and Recovery of Motor Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2015, 21, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennell, K.L.; Lawford, B.J.; Metcalf, B.; Mackenzie, D.; Russell, T.; van den Berg, M.; Finnin, K.; Crowther, S.; Aiken, J.; Fleming, J.; et al. Physiotherapists and Patients Report Positive Experiences Overall with Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Study. J. Physiother. 2021, 67, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seron, P.; Oliveros, M.J.; Gutierrez-Arias, R.; Fuentes-Aspe, R.; Torres-Castro, R.C.; Merino-Osorio, C.; Nahuelhual, P.; Inostroza, J.; Jalil, Y.; Solano, R.; et al. Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation in Physical Therapy: A Rapid Overview. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, E.; Gill, S.T.; Hayes, L.K.; Walker, T.L.; Walsh, M.; Kumar, S. Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation in the Management of Adults with Stroke: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhorne, P.; Coupar, F.; Pollock, A. Motor Recovery after Stroke: A Systematic Review. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahlberg, B.; Lindmark, B.; Zetterberg, L.; Hellström, K.; Cederholm, T. Body Composition and Physical Function after Progressive Resistance and Balance Training among Older Adults after Stroke: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirbekova, M.; Kispayeva, T.; Adomaviciene, A.; Eszhanova, L.; Bolshakova, I.; Ospanova, Z. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Effectiveness of Robotic Therapy in the Recovery of Motor Functions after Stroke. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1622661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duijnhoven, H.J.R.; Heeren, A.; Peters, M.A.M.; Veerbeek, J.M.; Kwakkel, G.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Weerdesteyn, V. Effects of Exercise Therapy on Balance Capacity in Chronic Stroke. Stroke 2016, 47, 2603–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todhunter-Brown, A.; Sellers, C.E.; Baer, G.D.; Choo, P.L.; Cowie, J.; Cheyne, J.D.; Langhorne, P.; Brown, J.; Morris, J.; Campbell, P. Physical Rehabilitation Approaches for the Recovery of Function and Mobility Following Stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2, CD001920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S.; Cacciante, L.; Cieślik, B.; Turolla, A.; Agostini, M.; Kiper, P.; Picelli, A. Telerehabilitation for Neurological Motor Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Quality of Life, Satisfaction, and Acceptance in Stroke, Multiple Sclerosis, and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, F.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Petracca, M.; Lo Monaco, M.R.; Ricciardi, D.; Di Caro, F.; Fragapane, S.; Giovannini, S.; Iacovelli, C.; Castelli, L.; et al. An Early Feasibility Study for Neurological Devices: The ARCTRAN Study. Neurol. Sci. 2025, 46, 5221–5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, K.; Thilarajah, S.; Pua, Y.-H.; Williams, G.; Tan, D.; Mentiplay, B.; Denehy, L.; Clark, R. Dynamic Balance and Instrumented Gait Variables Are Independent Predictors of Falls Following Stroke. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2019, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, D.H.; Mead, G.E.; Fitzsimons, C.; Kelly, P.; van Wijck, F.; Verschuren, O.; Backx, K.; English, C. Interventions for Reducing Sedentary Behaviour in People with Stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 6, CD012996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Falls. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Giovannini, S.; Brau, F.; Galluzzo, V.; Santagada, D.A.; Loreti, C.; Biscotti, L.; Laudisio, A.; Zuccalà, G.; Bernabei, R. Falls among Older Adults: Screening, Identification, Rehabilitation, and Management. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Kumar, C. The Patient Who Falls: “It’s Always a Trade-Off”. JAMA—J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2010, 303, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, S.; Chivers-Seymour, K.; Summers, R.; Lamb, S.; Goodwin, V.; Rochester, L.; Nieuwboer, A.; Rowsell, A.; Ewing, S.; Ashburn, A. ‘PDSAFE’—A Multi-Dimensional Model of Falls-Rehabilitation for People with Parkinson’s. A Mixed Methods Analysis of Therapists’ Delivery and Experience. Physiotherapy 2021, 110, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coote, S.; Comber, L.; Quinn, G.; Santoyo-Medina, C.; Kalron, A.; Gunn, H. Falls in People with Multiple Sclerosis: Risk Identification, Intervention, and Future Directions. Int. J. MS Care 2020, 22, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, A.; Wong, J.S.; McIlroy, W.E.; Biasin, L.; Brunton, K.; Bayley, M.; Inness, E.L. Do Measures of Reactive Balance Control Predict Falls in People with Stroke Returning to the Community? Physiotherapy 2015, 101, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolze, H.; Klebe, S.; Zechlin, C.; Baecker, C.; Friege, L.; Deuschl, G. Falls in Frequent Neurological Diseases: Prevalence, Risk Factors and Aetiology. J. Neurol. 2004, 251, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, L.Z.; Josephson, K.R. Falls and Their Prevention in Elderly People: What Does the Evidence Show? Med. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 90, 807–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt, A.; Hostettler, P.; Widmer, L.; Reuter, K.; Petersen, J.A.; Straumann, D.; Filli, L. Fall-Related Functional Impairments in Patients with Neurological Gait Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrington, C.; Fairhall, N.J.; Wallbank, G.K.; Tiedemann, A.; Michaleff, Z.A.; Howard, K.; Clemson, L.; Hopewell, S.; Lamb, S.E. Exercise for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, CD012424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalia, G.F.; Papalia, R.; Balzani, L.A.D.; Torre, G.; Zampogna, B.; Vasta, S.; Fossati, C.; Alifano, A.M.; Denaro, V. The Effects of Physical Exercise on Balance and Prevention of Falls in Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morat, T.; Snyders, M.; Kroeber, P.; De Luca, A.; Squeri, V.; Hochheim, M.; Ramm, P.; Breitkopf, A.; Hollmann, M.; Zijlstra, W. Evaluation of a Novel Technology-Supported Fall Prevention Intervention—Study Protocol of a Multi-Centre Randomised Controlled Trial in Older Adults at Increased Risk of Falls. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermair, I.; Schwertfeger, J. Community Stroke Interventions Do Not Address Participation and Environment for Stroke Survivors: Exploring Stroke Self-Management Interventions Using the ICF Framework. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2025, 106, e67–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, K.K.; Pamula, S.; Tendolkar, P.; Chen, P.; Suviseshamuthu, E.S. Preliminary Validation of an Objective Fall-Risk Assessment for Individuals with Stroke. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Rehabilitation. World Report On Disability; WHO Press, Ed.; WHO Press: Geneve, Switzerland, 2011; pp. 93–134. ISBN 9789241564182. [Google Scholar]

- ARC Intellicare—Dispositivo Medico Di Teleriabilitazione. Available online: https://www.arc-intellicare.com/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoehn, M.M.; Yahr, M.D. Parkinsonism: Onset, Progression and Mortality. Neurology 1967, 17, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; et al. Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis: 2017 Revisions of the McDonald Criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating Neurologic Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis: An Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.T.L.; Hareendran, A.; Hendry, A.; Potter, J.; Bone, I.; Muir, K.W. Reliability of the Modified Rankin Scale across Multiple Raters: Benefits of a Structured Interview. Stroke 2005, 36, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E. Performance-Oriented Assessment of Mobility Problems in Elderly Patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1986, 34, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capecci, M.; Cima, R.; Barbini, F.A.; Mantoan, A.; Sernissi, F.; Lai, S.; Fava, R.; Tagliapietra, L.; Ascari, L.; Izzo, R.N.; et al. Telerehabilitation with ARC Intellicare to Cope with Motor and Respiratory Disabilities: Results about the Process, Usability, and Clinical Effect of the “Ricominciare” Pilot Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceravolo, M.G.; Arienti, C.; de Sire, A.; Andrenelli, E.; Negrini, F.; Lazzarini, S.G.; Patrini, M.; Negrini, S. Rehabilitation and COVID-19: The Cochrane Rehabilitation 2020 Rapid Living Systematic Review. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 56, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stookey, A.D.; Katzel, L.I.; Steinbrenner, G.; Shaughnessy, M.; Ivey, F.M. The Short Physical Performance Battery as a Predictor of Functional Capacity after Stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2014, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Learmonth, Y.C.; Wójcicki, T.R.; Fanning, J.; Hubbard, E.A.; Kinnett-Hopkins, D.; Roberts, S.A.; McAuley, E. Preliminary Validation of the Short Physical Performance Battery in Older Adults with Multiple Sclerosis: Secondary Data Analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2015, 15, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanji, H.; Gruber-Baldini, A.L.; Anderson, K.E.; Pretzer-Aboff, I.; Reich, S.G.; Fishman, P.S.; Weiner, W.J.; Shulman, L.M. A Comparative Study of Physical Performance Measures in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2008, 23, 1897–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, C.U.; Danielsson, A.; Sunnerhagen, K.S.; Grimby-Ekman, A.; Hansson, P.O. Timed Up & Go as a Measure for Longitudinal Change in Mobility after Stroke—Postural Stroke Study in Gothenburg (POSTGOT). J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastião, E.; Sandroff, B.M.; Learmonth, Y.C.; Motl, R.W. Validity of the Timed Up and Go Test as a Measure of Functional Mobility in Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 1072–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocera, J.R.; Stegemöller, E.L.; Malaty, I.A.; Okun, M.S.; Marsiske, M.; Hass, C.J. Using the Timed up & Go Test in a Clinical Setting to Predict Falling in Parkinson’s Disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1300–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canbek, J.; Fulk, G.; Nof, L.; Echternach, J. Test-Retest Reliability and Construct Validity of the Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment in People with Stroke. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2013, 37, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesio, L.; Perucca, L.; Franchignoni, F.P.; Battaglia, M.A. A Short Measure of Balance in Multiple Sclerosis: Validation through Rasch Analysis. Funct. Neurol. 1997, 12, 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Besios, T.; Nikolaos, A.; Vassilios, G.; Giorgos, M. Comparative reliability of tinetti mobility test and tug tests in people with neurological disorders. Int. J. Physiother. 2019, 6, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, A.; Grandas, F. Risk of Falls in Parkinson’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study of 160 Patients. Park. Dis. 2012, 2012, 362572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglia, J.A.; De Luca, A.; Squeri, V.; Ciaccia, L.; Sanfilippo, C.; Ungaro, S.; De Michieli, L. De Design and Development of a Novel Core, Balance and Lower Limb Rehabilitation Robot: Hunova®. In Proceedings of the IEEE 16th International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics (ICORR), Toronto, ON, Canada, 24–28 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 417–422. [Google Scholar]

- Castelli, L.; Iacovelli, C.; Loreti, C.; Malizia, A.M.; Barone Ricciardelli, I.; Tomaino, A.; Fusco, A.; Biscotti, L.; Padua, L.; Giovannini, S. Robotic-Assisted Rehabilitation for Balance in Stroke Patients (ROAR-S): Effects of Cognitive, Motor and Functional Outcomes. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 8198–8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelli, L.; Iacovelli, C.; Ciccone, S.; Geracitano, V.; Loreti, C.; Fusco, A.; Biscotti, L.; Padua, L.; Giovannini, S. RObotic-Assisted Rehabilitation of Lower Limbs for Orthopedic Patients (ROAR-O): A Randomized Controlled Trial. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannini, S.; Iacovelli, C.; Brau, F.; Loreti, C.; Fusco, A.; Caliandro, P.; Biscotti, L.; Padua, L.; Bernabei, R.; Castelli, L. RObotic-Assisted Rehabilitation for Balance and Gait in Stroke Patients (ROAR-S): Study Protocol for a Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2022, 23, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella, A.; de Luca, A.; Squeri, V.; Parodi, S.; Vallone, F.; Giorgeschi, A.; Senesi, B.; Zigoura, E.; Quispe Guerrero, K.L.; Siri, G.; et al. Development and Validation of a Robotic Multifactorial Fall-Risk Predictive Model: A One-Year Prospective Study in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julious, S.A. Sample Size of 12 per Group Rule of Thumb for a Pilot Study. Pharm. Stat. 2005, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurman, D.J.; Stevens, J.A.; Rao, J.K. Practice Parameter: Assessing Patients in a Neurology Practice for Risk of Falls (an Evidence-Based Review). Neurology 2008, 70, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, C.M.; Ramage, E.; McDonald, C.E.; Bicknell, E.; Hitch, D.; Fini, N.A.; Bower, K.J.; Lynch, E.; Vogel, A.P.; English, K.; et al. Co-Designing Resources for Rehabilitation via Telehealth for People with Moderate to Severe Disability Post Stroke. Physiotherapy 2024, 123, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, B.; Arena, S. The Short Physical Performance Battery as a Predictor of Functional Decline. Home Healthc. Now 2022, 40, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raîche, M.; Hébert, R.; Prince, F.; Corriveau, H. Screening Older Adults at Risk of Falling with the Tinetti Balance Scale. Lancet 2000, 356, 1001–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumway-Cook, A.; Brauer, S.; Woollacott, M. Predicting the Probability for Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults Using the Timed Up & Go Test. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, S.; Staring, W.; Kunkel, D.; Pickering, R.M.; Lennon, S.; Geurts, A.C.; Weerdesteyn, V.; Verheyden, G.S. Interventions for Preventing Falls in People after Stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD008728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, I.-H.; Shin, W.-S.; Choi, K.-S.; Lee, M.-S. Effects of Real-Time Feedback Methods on Static Balance Training in Stroke Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2024, 12, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, C.; Nayyar, R.; Blennerhassett, J.; Egerton, T.; Tan, J.; Bower, K. Is Telehealth an Effective and Feasible Option for Improving Falls-Related Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Adults with Neurological Conditions? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2023, 37, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.C.; Lin, C.H.; Su, S.W.; Chang, Y.T.; Lai, C.H. Feasibility and Effect of Interactive Telerehabilitation on Balance in Individuals with Chronic Stroke: A Pilot Study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshari, M.; Hernandez, A.V.; Joyce, J.M.; Hauptschein, A.W.; Trenkle, K.L.; Stebbins, G.T.; Goetz, C.G. A Novel Home-Based Telerehabilitation Program Targeting Fall Prevention in Parkinson Disease: A Preliminary Trial. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2024, 14, e200246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alayat, M.S.; Almatrafi, N.A.; Almutairi, A.A.; El Fiky, A.A.R.; Elsodany, A.M. The Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation on Balance and Functional Mobility in Patients with Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Telerehabil. 2022, 14, e6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, F.; Powell, P.; McBride, C.; Monaghan, K. Physical Telerehabilitation Interventions for Gait and Balance in Multiple Sclerosis: A Scoping Review. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 456, 122827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, T.; Barer, Y.; Bitan, M.; Sobol, S.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M. A Meta-Analysis Identifies Factors Predicting the Future Development of Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease. Npj Park. Dis. 2023, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, L.; Giovannini, S.; Iacovelli, C.; Fusco, A.; Pastorino, R.; Marafon, D.P.; Pozzilli, C.; Padua, L. Training-Dependent Plasticity and Far Transfer Effect Enhanced by Bobath Rehabilitation in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 68, 104241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, N.; Bamutraf, O.; Mukhtar, S.; Mazi, A.; Jawad, A.; Khan, A.; Alqarni, A.M.; Basuodan, R.; Khan, F. Exploring Key Factors Associated with Falls in People with Multiple Sclerosis: The Role of Trunk Impairment and Other Contributing Factors. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheyden, G.; Nieuwboer, A.; De Wit, L.; Feys, H.; Schuback, B.; Baert, I.; Jenni, W.; Schupp, W.; Thijs, V.; De Weerdt, W. Trunk Performance after Stroke: An Eye Catching Predictor of Functional Outcome. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 78, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikbabu, S.; Chakrapani, M.; Ganeshan, S.; Rakshith, K.C.; Nafeez, S.; Prem, V. A Review on Assessment and Treatment of the Trunk in Stroke: A Need or Luxury. Neural Regen. Res. 2012, 7, 1974–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artigas, N.R.; Franco, C.; Leão, P.; Rieder, C.R.M. Postural Instability and Falls Are More Frequent in Parkinson’s Disease Patients with Worse Trunk Mobility. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2016, 74, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelli, L.; Loreti, C.; Malizia, A.M.; Iacovelli, C.; Renzi, S.; Fioravanti, L.; Amoruso, V.; Paolasso, I.; Di Caro, F.; Padua, L.; et al. The Impact of RObotic Assisted Rehabilitation on Trunk Control in Patients with Severe Acquired Brain Injury (ROAR-SABI). Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, S.; Bruce, J.; Skelton, D.A.; Withers, E.J.; Lamb, S.E. Development and Delivery of an Exercise Programme for Falls Prevention: The Prevention of Falls Injury Trial (PreFIT). Physiotherapy 2018, 104, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, S.; Seers, K.; Bruce, J. Long-Term Follow-up of Exercise Interventions Aimed at Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Physiotherapy 2019, 105, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir-Hunter, S.W.; Wittwer, J.E. Dual-Task Testing to Predict Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Physiotherapy 2016, 102, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ARC Intellicare Group | Paper-Based Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Whole sample | n = 43 | n = 46 |

| Gender, n (%) Male Female | 24 (55.81%) 19 (44.19%) | 22 (47.83%) 24 (52.17%) |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 56.93 ± 13.01 | 55.15 ± 13.87 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 24.66 ± 12.99 | 24.58 ± 14.04 |

| Falls, n (%) No falls At least one fall in the last 12 months More than two falls in the last 12 months | 39 (43.33%) 4 (4.44%) 2 (2.22%) | 35 (38.89%) 5 (5.56%) 5 (5.56%) |

| SPPB T0, mean ± SD | 8.64 ± 2.07 | 8.68 ± 2.09 |

| TUG, mean ± SD | 30.99 ± 33.26 | 37.14 ± 35.78 |

| TINETTI total score T0, mean ± SD | 24.77 ± 2.62 | 25.30 ± 2.47 |

| SILVER INDEX T0, mean ± SD | 26.90 ± 17.90 | 28.20 ± 13.10 |

| Stroke | n = 14 | n = 15 |

| Gender, n (%) Male Female | 9 (64.29%) 5 (35.71%) | 9 (60.00%) 6 (40.00%) |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 63.93 ± 7.87 | 64.33 ± 7.35 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 23.62 ± 4.00 | 25.95 ± 3.58 |

| Falls, N (%) No falls At least one fall in the last 12 months More than two falls in the last 12 months | 14 (15.56%)00 | 14 (15.56%) 1 (1.11%) 1 (1.11%) |

| DOD (yr), mean ± SD | 3.82 ± 0.47 | 1.73 ± 0.46 |

| MRS T0, mean ± SD | 2.14 ± 0.36 | 2.33 ± 0.49 |

| SPPB T0, mean ± SD | 8.57 ± 1.74 | 8.07 ± 2.49 |

| TUG, mean ± SD | 24.59 ± 28.59 | 29.21 ± 28.86 |

| TINETTI total score T0, mean ± SD | 25.14 ± 1.83 | 25.73 ± 2.28 |

| SILVER INDEX T0, mean ± SD | 28.30 ± 12.20 | 29.40 ± 9.13 |

| Parkinson’s Disease | n = 14 | n = 16 |

| Gender, n (%) Male Female | 9 (62.28%) 5 (35.71%) | 8 (50%) 8 (50%) |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 66.07 ± 5.66 | 61.93 ± 6.20 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 25.00 ± 7.58 | 23.9 ± 2.50 |

| Falls, n (%) No falls At least one fall in the last 12 months More than two falls in the last 12 months | 15 (16.67%) 1 (1.11%) 0 (0%) | 12 (13.33%) 1 (1.11%) 1 (1.11%) |

| DOD (yr), mean ± SD | 6.14 ± 1.88 | 6.50 ± 3.10 |

| mean ± SD | 1.93 ± 0.58 | 2.09 ± 0.46 |

| SPPB T0, mean ± SD | 9.81 ± 1.80 | 9.29 ± 1.68 |

| TUG, mean ± SD | 44.33 ± 39.88 | 28.30 ± 34.32 |

| TINETTI total score T0, mean ± SD | 25.79 ± 1.81 | 25.19 ± 2.64 |

| SILVER INDEX T0, mean ± SD | 25.40 ± 15.60 | 24.10 ± 14.50 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | n = 15 | n = 15 |

| Gender, n (%) Male Female | 6 (40%) 9 (60%) | 5 (33.33%) 10 (66.67%) |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 41.87 ± 6.69 | 38.73 ± 9.57 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 22.4 ± 6.58 | 21.03 ± 6.45 |

| Falls, n (%) No falls At least one fall in the last 12 months More than two falls in the last 12 months | 10 (11.11%) 3 (3.33%) 2 (2.22) | 9 (10.00%) 3 (3.33%) 3 (3.33%) |

| DOD (yr), mean ± SD | 3.83 ± 6.81 | 4.21 ± 9.09 |

| EDSS T0, mean ± SD | 3.87 ± 1.28 | 3,84 ± 1,03 |

| SPPB T0, mean ± SD | 7.47 ± 2.03 | 8.73 ± 1.94 |

| TUG, mean ± SD | 22.76 ± 26.39 | 53.31 ± 39.75 |

| TINETTI total score T0, mean ± SD | 23.47 ± 3.38 | 25.00 ± 1.46 |

| SILVER INDEX T0, mean ± SD | 34.30 ± 23.90 | 30.60 ± 16.40 |

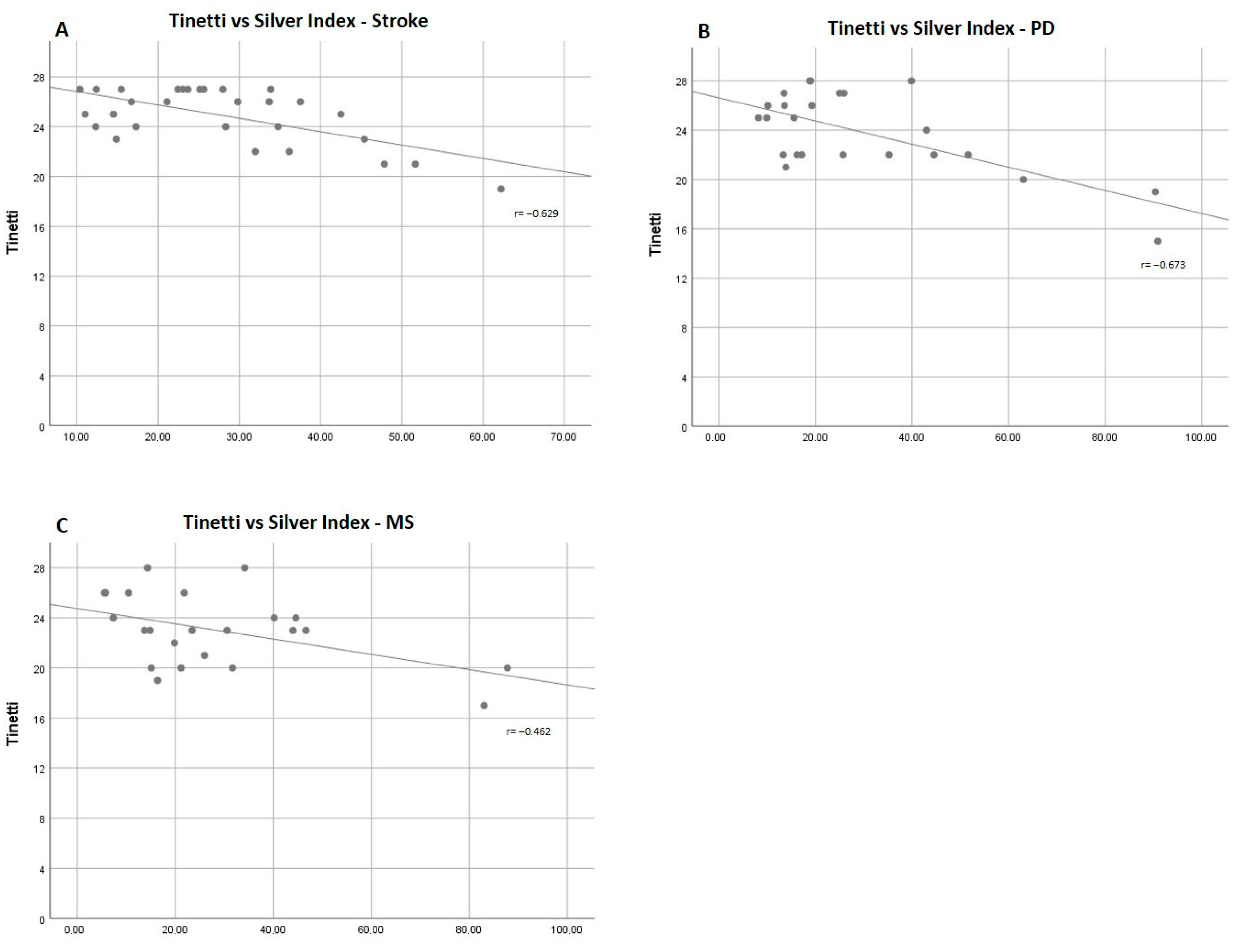

| Mean ± SD | r | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke | |||

| SPPB | 8.31 ± 2.14 | −0.470 | 0.010 |

| TUG | 27.30 ± 28.31 | 0.341 | 0.071 |

| Tinetti | 25.47 ± 2.06 | −0.629 | <0.001 |

| Parkinson’s Disease | |||

| SPPB | 9.57 ± 1.74 | −0.750 | <0.001 |

| TUG | 36.85 ± 37.64 | 0.488 | 0.013 |

| Tinetti | 25.47 ± 2.21 | −0.673 | <0.001 |

| Multiple Sclerosis | |||

| SPPB | 8.10 ± 2.06 | −0.747 | <0.001 |

| TUG | 38.03 ± 36.61 | 0.441 | 0.035 |

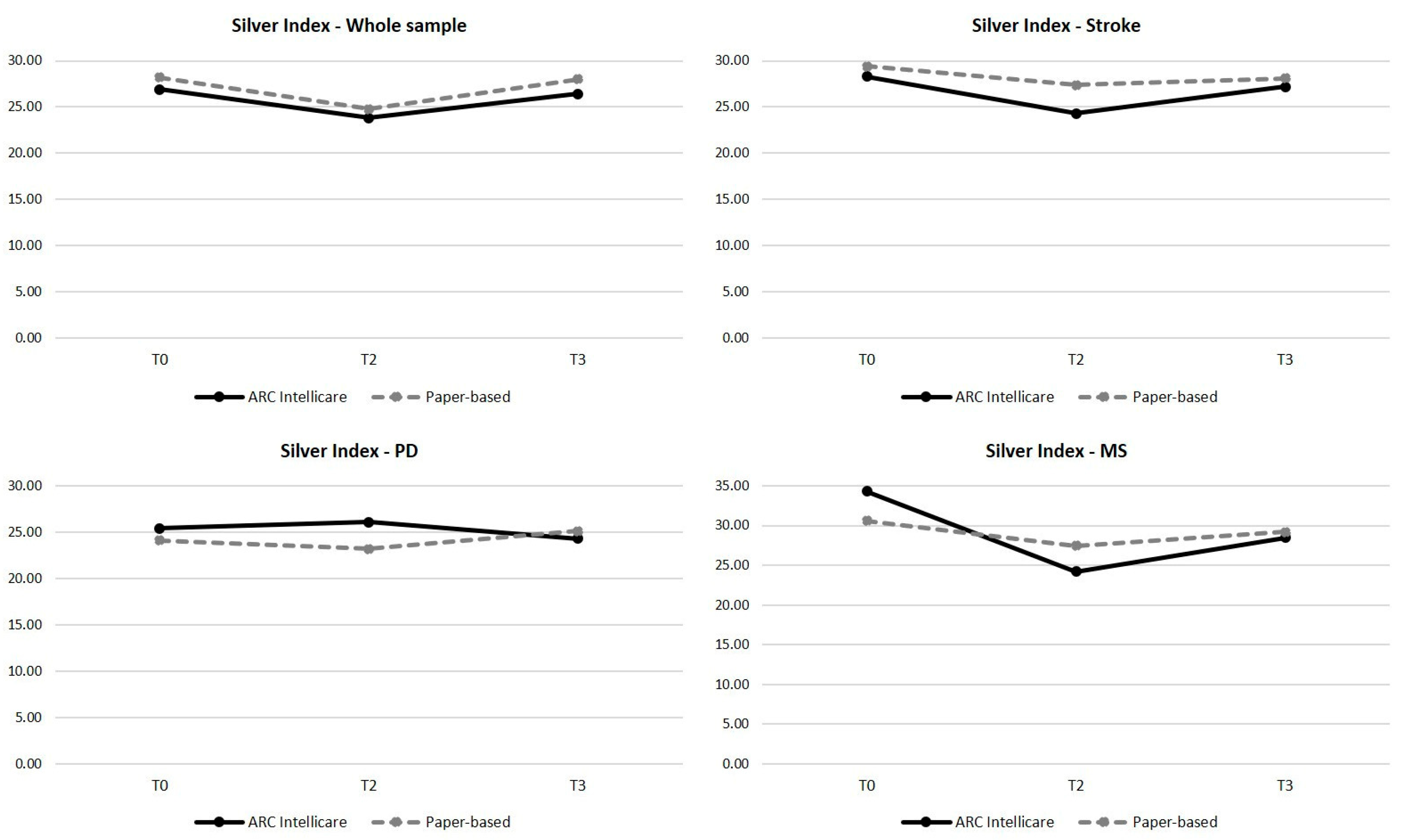

| Post Hoc Test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 Mean ± SD | T2 Mean ± SD | T3 Mean ± SD | p Value | T0 vs. T2 | T2 vs. T3 | |

| ARC Intellicare group | ||||||

| Whole Sample | 26.90 ± 17.90 | 23.80 ± 13.80 | 26.40 ± 16.60 | 0.227 | - | - |

| Stroke | 28.30 ± 12.20 | 24.30 ± 14.40 | 27.21 ± 17.80 | 0.425 | - | - |

| Parkinson’s Disease | 25.40 ± 15.60 | 26.10 ± 14.40 | 24.30 ± 10.10 | 0.222 | - | - |

| Multiple sclerosis | 34.30 ± 23.90 | 24.20 ± 13.80 | 28.49 ± 26.30 | 0.006 | 0.015 | 0.357 |

| Paper-based group | ||||||

| Whole Sample | 28.20 ± 13.10 | 24.80 ± 15.40 | 28.00 ± 18.20 | 0.932 | - | - |

| stroke | 29.40 ± 9.13 | 27.40 ± 20.10 | 28.10 ± 15.80 | 0.164 | - | - |

| Parkinson’s Disease | 24.10 ± 14.50 | 23.20 ± 10.60 | 25.10 ± 15.00 | 0.928 | - | - |

| Multiple Sclerosis | 30.60 ± 16.40 | 27.45 ± 14.00 | 29.20 ± 23.00 | 0.587 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castelli, L.; Iacovelli, C.; Malizia, A.M.; Loreti, C.; Biscotti, L.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Calabresi, P.; Giovannini, S. A New Assessment Tool for Risk of Falling and Telerehabilitation in Neurological Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Ancillary Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011247

Castelli L, Iacovelli C, Malizia AM, Loreti C, Biscotti L, Bentivoglio AR, Calabresi P, Giovannini S. A New Assessment Tool for Risk of Falling and Telerehabilitation in Neurological Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Ancillary Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011247

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastelli, Letizia, Chiara Iacovelli, Anna Maria Malizia, Claudia Loreti, Lorenzo Biscotti, Anna Rita Bentivoglio, Paolo Calabresi, and Silvia Giovannini. 2025. "A New Assessment Tool for Risk of Falling and Telerehabilitation in Neurological Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Ancillary Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011247

APA StyleCastelli, L., Iacovelli, C., Malizia, A. M., Loreti, C., Biscotti, L., Bentivoglio, A. R., Calabresi, P., & Giovannini, S. (2025). A New Assessment Tool for Risk of Falling and Telerehabilitation in Neurological Diseases: A Randomized Controlled Ancillary Study. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011247