Summation by Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Experimental Design

3. Results and Discussion

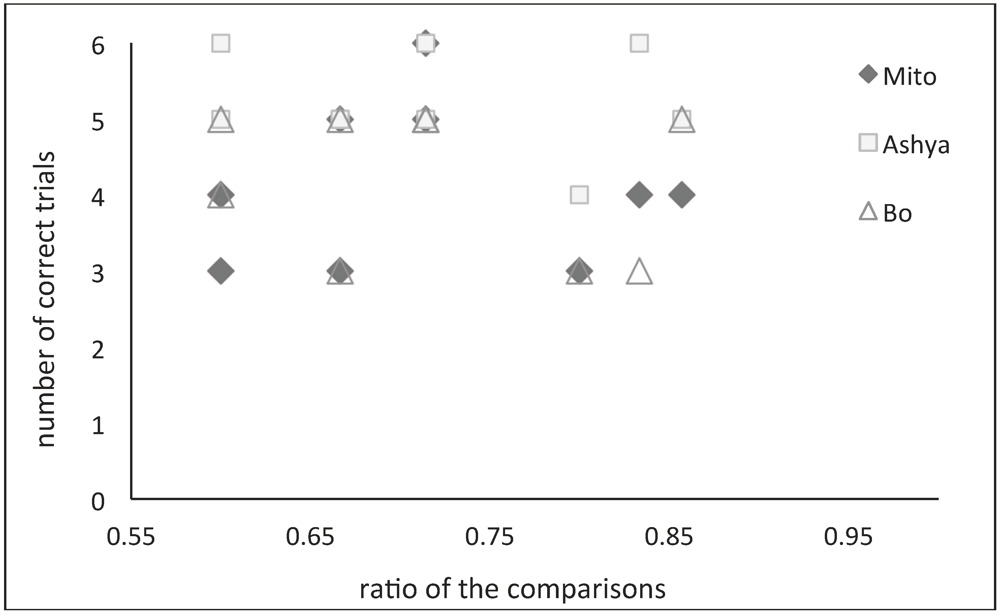

| Sums | 3 vs. 5 | 3 vs. 5 | 4 vs. 5 | 4 vs. 6 | 4 vs. 6 | 5 vs. 6 | 5 vs. 6 | 5 vs. 7 | 5 vs. 7 | 5 vs. 7 | 6 vs. 7 | 6 vs. 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula | 1 + 2 | 2 + 1 | 3 + 1 | 2 + 2 | 1 + 3 | 4 + 1 | 1 + 4 | 3 + 2 | 3 + 2 | 2 + 3 | 5 + 1 | 1 + 5 |

| vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | vs. | |

| 1 + 4 | 1 + 4 | 1 + 4 | 2 + 4 | 5 + 1 | 3 + 3 | 3 + 3 | 5 + 2 | 2 + 5 | 5 + 2 | 3 + 4 | 3 + 4 | |

| Mito | 3 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | - | 5 | 6 | - | 4 | - |

| Ashya | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Bo | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Uller, C.; Jaeger, R.; Guidry, G.; Martin, C. Salamanders (plethodon cinereus) go for more: Rudiments of number in an amphibian. Anim. Cogn. 2003, 6, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Agrillo, C.; Dadda, M.; Bisazza, A. Quantity discrimination in female mosquitofish. Anim. Cogn. 2007, 10, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Olthof, A.; Roberts, W.A. Summation of symbols by pigeons (columba livia): The important number and mass of reward items. J. Comp. Psychol. 2000, 114, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrell, D.F.; Thomas, R.K. Number-related discrimination and summation by squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus sciureus and S. boliviensus boliviensus) on the basis of the number of sides of polygons. J. Comp. Psychol. 1990, 104, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.K.; Chase, L. Relative numerousness judgments by squirrel monkeys. B. Psychonomic. Soc. 1980, 16, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Beran, M.J. Rhesus monkeys (macaca mulatta) enumerate large and small sequentially presented sets of items using analog numerical representations. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. B. 2007, 33((1)), 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, U.S.; Stoinski, T.S.; Bloomsmith, M.A.; Marr, M.J.; Smith, A.D.; Maple, T.L. Relative numerousness judgment and summation in young and old western lowland gorillas. J. Comp. Psychol. 2005, 119, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Call, J. Estimating and operating on discrete quantities in orangutans (pongo pygmaeus). J. Comp. Psychol. 2000, 114, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, U.S.; Stoinski, T.S.; Bloomsmith, M.A.; Maple, T.L. Relative numerousness judgment and summation in young, middle-aged, and older adult orangutans (pongo pygmaeus ablii and pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus). J. Comp. Psychol. 2007, 121, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beran, M. Summation and numerousness judgments of sequentially presented sets of items by chimpanzees (pan troglodytes). J. Comp. Psychol. 2001, 115, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysen, S.T.; Bernston, G.G.; Mukobi, K.L. Size matters: Impact of item size and quantity on array choice by chimpanzees (pan troglodytes). J. Comp. Psychol. 2001, 115, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perusse, R.; Rumbaugh, D.M. Summation in chimpanzees (pan troglodytes): Effects of amounts, number of wells, and finer ratios. Int. J. Primatol. 1990, 11((5)), 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallistel, C.R.; Gelman, R. Non-verbal numerical cognition: from reals to integers. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4((2)), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, M.D.; Carey, S.; Hauser, L.B. Spontaneous number representation in semi-free-ranging rhesus monkeys. R. Soc. Lond. 2000, B267, 829–833. [Google Scholar]

- Agrillo, C.; Piffer, L.; Bisazza, A.; Butterworth, B. Evidence for two numerical systems that are similar in humans and guppies. Plos One 2012, 7((2)). [Google Scholar]

- Irie-Sugimoto, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Sato, T.; Hasegawa, T. Relative quantity judgment by Asian elephants (elephas maximus). Anim. Cogn. 2009, 12, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.; Wittemyer, G. A comparison of social organization in Asian elephants and African savannah elephants. Int. J. Primatol. 2012, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, L.A.; Sayialel, K.N.; Njiraini, N.W.; Poole, J.H.; Moss, C.J.; Byrne, R.W. African elephants have expectations about the locations of out-of-sight family members. Biol. Letters. 2008, 4, 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumbaugh, D.M.; Savage-Rumbaugh, S.; Hegel, M.T. Summation in the chimpanzee (pan troglodytes). J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. B. 1987, 13((2)), 107–115. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Irie, N.; Hasegawa, T. Summation by Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus). Behav. Sci. 2012, 2, 50-56. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs2020050

Irie N, Hasegawa T. Summation by Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus). Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 2(2):50-56. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs2020050

Chicago/Turabian StyleIrie, Naoko, and Toshikazu Hasegawa. 2012. "Summation by Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus)" Behavioral Sciences 2, no. 2: 50-56. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs2020050