“You Know It, You Can Do It—Good Luck!”: Managing Music Performance Anxiety in the Context of Transforming Music Performance Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Musical Self-Concept Within Ecosystemic Perspectives on MPA

1.2. Aim and Research Questions

- What interactions in music performance ecosystems shape the experience of MPA?

- How are these interactions related to the performer’s musical self-concept?

- How can the interplay of social, educational, cultural, technological, and other environmental factors contribute to the formation of ecosystems that reduce the risk of developing MPA?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Interview Protocol

2.4. Data Preparation and Analysis

2.5. Rigor and Validation

3. Results

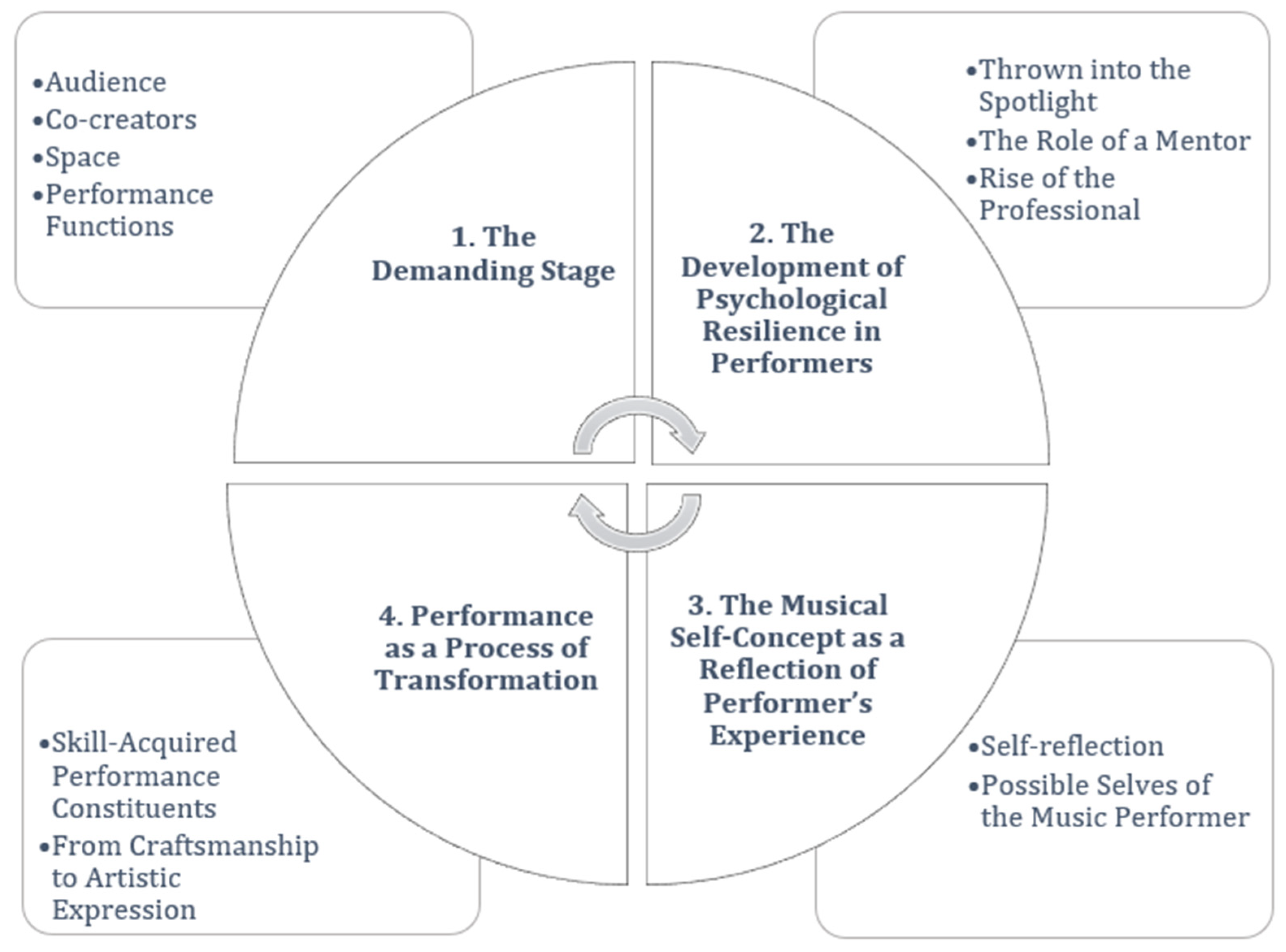

3.1. The Demanding Stage

3.1.1. Audience

“Playing for a panel—for someone who’s been sitting there for four or five hours as part of their job—I know it’s hard for them to listen to every next person, no matter how they play. It’s just not easy to sit there. And I find it really hard to play for that kind of panel.”

“That interaction with the audience, meaning it’s not just me and the piece I have to play as perfectly as possible, but I have started to open up more and more to the audience itself and to sense their reactions—that sometimes we were almost breathing together or were left breathless at certain moments.”

3.1.2. Space

“You can’t let any distractions throw you off—like someone coughing, people coming in and out, someone taking pictures up close, flashing lights, a detuned piano, the stage creaking, the piano bench squeaking, or the pedal squeaking…”

3.1.3. Co-Creators

3.1.4. Performance Functions

“…then they had to record me in front of the whole orchestra because they were recording a CD. I have to admit–that was huge pressure. You don’t want to disappoint the director, I mean the conductor, or the people who are recording, because then they’d have to do the take ten more times because of you, not to mention the others waiting to see if you did it well or not…”

“When I know it’s just an event, some pop thing… I don’t worry much about the performance. I once played for two hours as guests were arriving—it’s the easiest kind of performance. It’s not that technical, and even if something goes wrong, it doesn’t matter; no one is listening closely”[P1].

“So, I was really nervous. And I had to play in the G. Hall, then they told me the president of the country would come, and that after the concert I’d have to put on a tie and go meet him, and all that stuff. After that performance, I wondered if I even wanted to do this.”

3.2. The Development of Psychological Resilience in Performers

3.2.1. Thrown into the Spotlight

“I was simply faced with the fact that I had to perform, so I got up there. And however it goes, it goes.” Participant P3 statement points to an institutional gap: “In the education system there isn’t much emphasis on how to cope with stage fright—we’re left to our own devices.”

“Classroom recitals would really help: the more often you run a piece—also at different stages of mastery—the more confident you become, the better you know how to react, and the clearer the whole situation feels”[P1].

3.2.2. The Role of a Mentor

3.2.3. Rise of a Professional

3.3. The Musical Self-Concept as a Reflection of the Performer’s Experience

3.3.1. Self-Reflection

“It’s important that I take a moment to relax and tell myself that I’m ready. I listen to my body, give myself positive thoughts, and say to myself that it’s going to be okay.”[P10]

“…wait, what is this? Why am I suddenly shaking like this? And what if that happens to me right in the middle of the stage? What if things just start falling apart…”

“I won’t let this bring me down. Just focus, it will be fine. Just stay calm, just stay calm.”

“And of course, during the performance, that critical thinking kicks in: what are you going to do so it work… Yeah okay, that last bit wasn’t exactly brilliant… That inner critic starts chiming in with all sorts of ideas. It’s pretty uuuuuuuu [foreboding groan].”

“…it went wrong, and I know how I could change it next time, but now I’m just going to keep playing…”

3.3.2. Possible Selves of the Music Performer

“So, a circus performer must not have breadth—must not allow it—because when doing that triple somersault, God forbid he thinks of anything else, or he’ll die. And for me, it’s the same during the Bartók concerto on the viola.”[P8]

- The musician as a virtuoso, “circus performer”—narrowly defined roles, “shallow” dedication to producing flawless artistic performances.

- The musician as a craftsman—conscientious and flawless, but an unemotional performer of a “commission.”

- The musician as intellectual, artist—a comprehensively educated and spiritually awakened creator.

- The musician as researcher—a role focused on the search for new challenges and ways of making music.

- The musician as an athlete—a professional who complements their performing discipline and fitness with approaches from sport psychology.

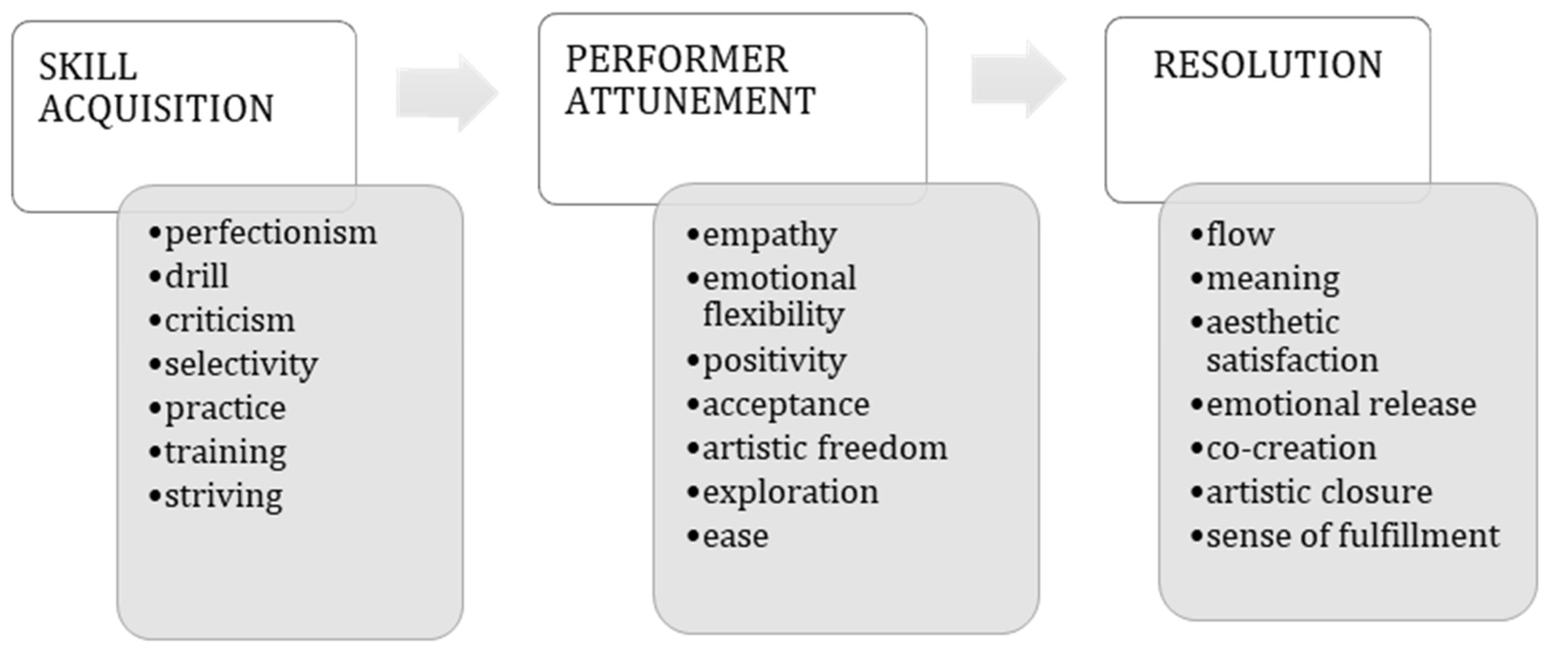

3.4. Performance as a Process of Transformation

3.4.1. Skill-Acquired Performance Constituents

3.4.2. From Craftsmanship to Artistic Expression

“Perfectionism is incredibly present. You have to become aware of what really matters. Is it important to play all the notes precisely and in perfect rhythm—or is there more to it? Is it important how warmly you play, what kind of ‘air’ your phrase carries? … Does the phrase have direction, a line, or is everything static and without feeling—like you’re just pushing keys on a machine? Do you even like what you’re playing? Are we enjoying it? Does it have character? … I wanted to shift the focus to this—not just to notes and a metronome. Of course, that’s the foundation, but that’s practice, drill… That’s another kind of development. That’s not an analytical mind, it’s different layers—the body, the feeling, the senses… It’s about an aesthetic sense that has to live inside you.”

“I once had a performance at the Academy of Music where I practically stepped out of my own body. I wasn’t here anymore—I saw myself from the outside… Everyone was amazed because it was an exceptional performance. I remember sitting at the piano, but I was up here somewhere, you see, and I was still functioning, but at the same time, I wasn’t really there, right?”

“This is a long-term, integrative development. You have to connect many things just to get close to great music.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary and Implications of Results

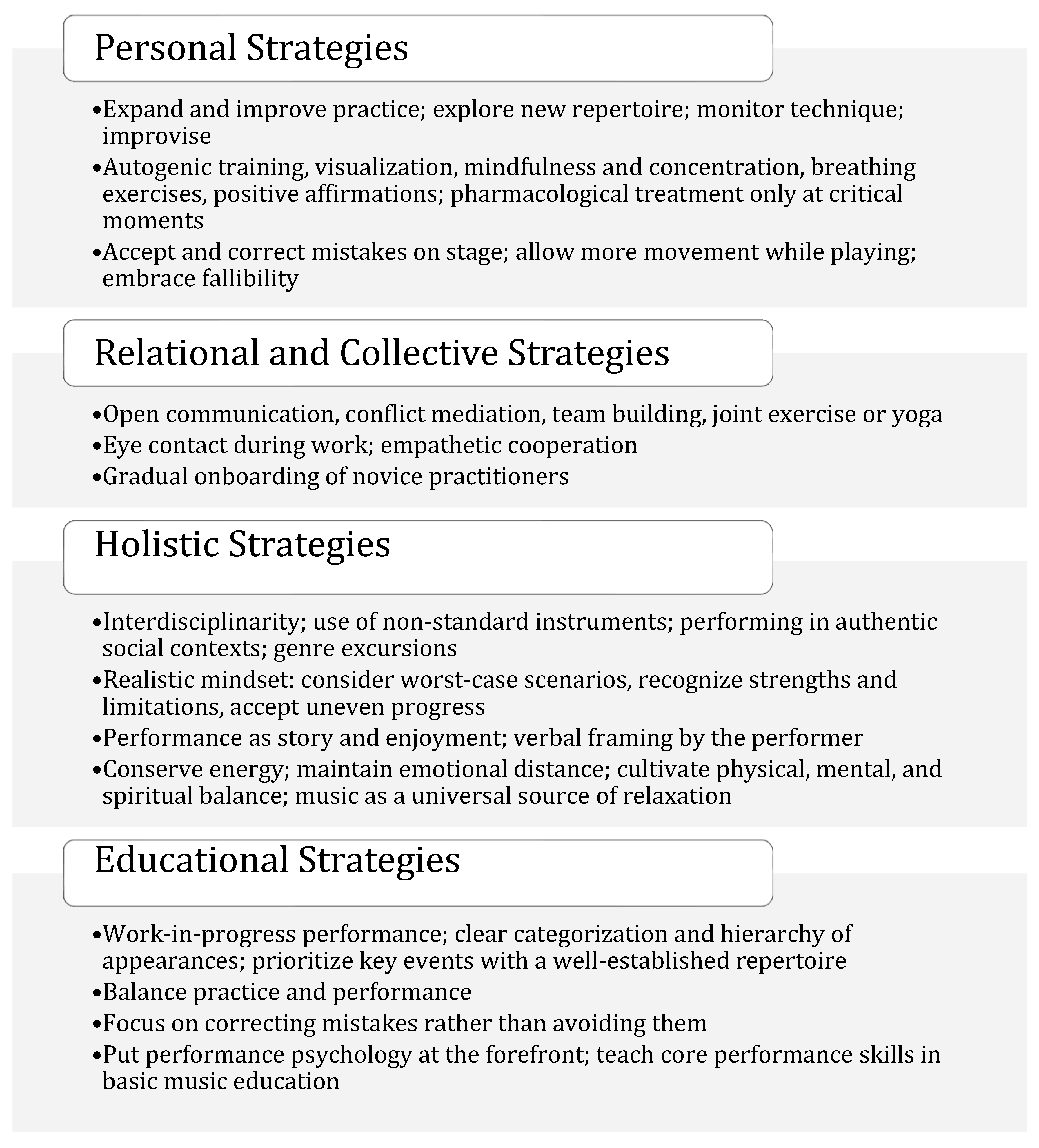

4.1.1. Theoretical Implications

4.1.2. Practical Implications

- introducing psychological performance skills early in training,

- balancing practice and performance opportunities,

- scaffolding with repertoire suited to developmental stages, and

- gradually increasing exposure to high-stakes situations (Kenny, 2005).

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahlén, J., Breitholtz, E., Barrett, P. M., & Gallegos, J. (2012). School-based prevention of anxiety and depression: A pilot study in Sweden. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 5(4), 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Banes, S., & Lepecki, A. (Eds.). (2012). The senses in performance. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D., & Ginsborg, J. (2018). Audience reactions to the program notes of unfamiliar music. Psychology of Music, 46(4), 588–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, M., & Frezza, L. (2009). Dimensions of music improvisation. Creativity Research Journal, 21(2–3), 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, S. J., & Davidson, J. W. (2002). Developing a child’s identity as a musician: A “family” script perspective. In R. A. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (Eds.), Musical identities (pp. 21–41). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Castiglione, C., Rampullo, A., & Cardullo, S. (2018). Self representations and music performance anxiety: A study with professional and amateur musicians. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 14(4), 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, E. F. (2005). Ways of listening: An ecological approach to the perception of musical meaning. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conable, B., & Conable, B. (1995). How to learn the alexander technique: A manual for students. Andover Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creech, A., & Hallam, S. (2011). Learning a musical instrument: The influence of interpersonal interaction on outcomes for school-aged pupils. Psychology of Music, 39(1), 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., Abuhamdeh, S., & Nakamura, J. (2014). Flow. In M. Csikszentmihalyi (Ed.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pp. 227–238). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J. W. (2002). The solo performer’s identity. In V. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, & D. Meill (Eds.), Musical identities (pp. 97–113). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J. W., Howe, M. J. A., & Sloboda, J. A. (1997). Environmental factors in the development of musical performance skill over the life span. In D. J. Hargreaves, & A. C. North (Eds.), The social psychology of music (pp. 188–206). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T. (2011). Towards a relational understanding of the performance ecosystem. Organised Sound, 16(2), 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeNora, T. (2017). Music ecology and everyday action. In R. MacDonald, D. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (Eds.), Music identities (pp. 53–66). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Paiva e Pona, E. (2016). Applying processes of the acceptance and commitment therapy to enhance music teaching and performance [Master’s thesis, Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität Linz]. Research Gate. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, C. L., & Spence, S. H. (2000). Prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(4), 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaunt, H., Duffy, C., Coric, A., González Delgado, I. R., Messas, L., Pryimenko, O., & Sveidahl, H. (2021). Musicians as “makers in society”: A conceptual foundation for contemporary professional higher music education. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 713648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J. J. (1977). The theory of affordances. In R. Shaw, & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, acting, and knowing: Toward an ecological psychology (pp. 67–82). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A., Osborne, M. S., & McPherson, G. (2024). Sources of self-efficacy in class and studio music lessons. Research Studies in Music Education, 46(1), 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsborg, J., & Chaffin, R. (2011). Preparation and spontaneity in performance: A singer’s thoughts while singing Schoenberg. Psychomusicology: Music, Mind, and Brain, 21(1), 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L. (2002). How popular musicians learn. A way ahead for music education. Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Haeckel, E. (1866). Generelle morphologie der organismen: Allgemeine grundzüge der organischen formen-wissenschaft, mechanisch begründet durch die von charles darwin reformirte descendenz-theorie (Vols. 1–2). Georg Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, T. N. (2013). The role of mentorship in the training of professional musicians. Journal of Arts Education, 1(1), 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, R., & Clark, T. (2023). It’s not a virus! Reconceptualizing and de-pathologizing music performance anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1194873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J. (2019). Music education for social change: Constructing an activist music education (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C. E. (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, C. E., Thompson, B. J., & Williams, E. N. (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25(4), 517–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, E. R. (2003). Transforming music education. Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Juncos, D. G., & Markman, E. J. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy for the treatment of music performance anxiety: A single-subject design with a university student. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 935–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslin, P. N., & Sloboda, J. A. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kegelaers, J., Bakker, F., Kouwenhoven, J., & Oudejans, R. (2023). “Don’t forget Shakespeare”: A qualitative pilot study into the performance evaluations of orchestra audition panelists. Psychology of Music, 51(1), 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. G. (1968). Toward an ecological conception of preventive interventions. In J. W. Carter (Ed.), Research contributions from psychology to community mental health (pp. 75–99). Behavioral Publications. (Original work published 1967). [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J. G. (2005). Becoming ecological: An expedition into community psychology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2005). A systematic review of treatments for music performance anxiety. Anxiety, Stress Coping, 18(3), 183–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. T. (2009). Music performance anxiety: New insights from young musicians. In G. E. McPherson (Ed.), Oxford handbook of music performance (Vol. 2, pp. 204–231). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2011). The psychology of music performance anxiety. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, D. T. (2023). The Kenny music performance anxiety inventory (K-MPAI): Scale construction, cross-cultural validation, theoretical underpinnings, and diagnostic and therapeutic utility. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1143359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivijärvi, S., & Väkevä, L. (2020). Considering equity in applying Western standard music notation from a social justice standpoint: Against the notation argument. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 19(1), 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, A. (1999, April). A contextual account of developing representations of music [Paper presentation]. International Conference on Research in Music Education, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, A. (2002). Musical identities and the school environment. In R. A. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (Eds.), Musical identities (pp. 41–60). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, C., & Georgii-Hemming, E. (2019). Improvisation in general music education—A literature review. British Journal of Music Education, 36(1), 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R., Hargreaves, D. J., & Miell, D. (Eds.). (2017). The oxford handbook of musical identities. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, R., & Saarikallio, S. (2024). Healthy musical identities and new virtuosities: A humble manifesto for music education research. Nordic Research in Music Education, 5, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, S. A. (2017). Young people’s musical lives: Identities, learning ecologies and connectedness. In R. A. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, & D. E. Miell (Eds.), Handbook of musical identities (pp. 79–104). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, M. S., & Kirsner, J. (2022). Music performance anxiety. In G. E. McPherson (Ed.), Oxford handbook of music performance (Vol. 2, pp. 204–231). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgi, I., Hallam, S., & Welch, G. (2007). A conceptual framework for understanding musical performance anxiety. Research Studies in Music Education, 28(1), 83–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partti, H., & Karlsen, S. (2010). Reconceptualising musical learning: New media, identity and community in music education. Music Education Research, 12(4), 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecen, E., Collins, D. J., & MacNamara, Á. (2018). Psychological distress and the music conservatoire student: A qualitative study of elite performers. Psychology of Music, 46(6), 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, K. (2009). Connections between performer and teacher identities in music teachers: Setting an agenda for research. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 19(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J., & Hendricks, K. S. (2019). Collective efficacy belief, within-group agreement, and performance quality among instrumental chamber ensembles. Journal of Research in Music Education, 66(4), 449–464, (Original work published 2018). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, M. (2012). Musical sense-making and the concept of affordance: An ecosemiotic and experiential approach. Biosemiotics, 5(3), 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, E., & Kiverstein, J. (2014). A rich landscape of affordances. Ecological Psychology, 26(4), 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R. K. (2006). Group creativity: Musical performance and collaboration. Psychology of Music, 34(2), 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, H., & Grant, C. F. (2016). Approaching music cultures as ecosystems: A dynamic model for understanding and supporting sustainability. In H. Schippers, & C. F. Grant (Eds.), Sustainable futures for music cultures: An ecological perspective (Chapter 12). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnare, B., MacIntyre, P., & Doucette, J. (2012). Possible selves as a source of motivation for musicians. Psychology of Music, 40(1), 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, G., & Nettl, B. (Eds.). (2009). Musical improvisation: Art, education, and society. University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spahn, C., Walther, J.-C., & Nusseck, M. (2016). The effectiveness of a multimodal concept of audition training for music students in coping with music performance anxiety. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spychiger, M. (2017). From musical experience to musical identity: Musical self-concept as a mediating psychological structure. In V. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, & D. Miell (Eds.), Handbook of musical identities (pp. 267–288). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spychiger, M., Gruber, L., & Olbertz, F. (2009). Musical self-concept-presentation of a multi-dimensional model and its empirical analyses. In J. Louhivuori, T. Eerola, S. Saarikallio, T. Himberg, & P. S. Eerola (Eds.), 7th Triennial Conference of European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music (ESCOM 2009) (pp. 503–506). Jyväskylä, Finland, Available online: https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/20934/urn_nbn_fi_jyu-2009411322.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Stoffregen, T. A., & Bardy, B. G. (2001). On specification and the senses. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(2), 195–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansley, A. G. (1935). The use and abuse of vegetational terms and concepts. Ecology, 16(3), 284–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. R. (2017). Feedback from research participants: Are member checks useful in qualitative research? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, G., & Williamon, A. (2022). Measuring the audience. In Scholarly research in music: Shared and disciplinary-specific practices (2nd ed., pp. 217–228). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, S. (2007). Performance ecosystems: Ecological approaches to musical interaction. Organised Sound, 12(1), 13–20. Available online: http://www.ems-network.org/IMG/pdf_WatersEMS07.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Webster, H. M. (2003). An ecological approach to the prevention of anxiety disorders during childhood [Doctoral dissertation, Griffith University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, H., Karlsen, S., Kallio, A. A., Treacy, D. S., Miettinen, L., Timonen, V., Gluschankof, C., Ehrlich, A., & Shah, I. B. (2022). Visions for intercultural music teacher education in complex societies. Research Studies in Music Education, 44(2), 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A., Vogel, D., Voss, C., & Hoyer, J. (2021). How does music performance anxiety relate to other anxiety disorders? Psychology of Music, 50(1), 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code (Performer/Number) | Gender, Age | Instrument | Years of Performing Career |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | F, 23 | Harp | 1 |

| P2 | M, 28 | Voice | 10 |

| P3 | F, 42 | Piano | 22 |

| P4 | M, 42 | Piano | 22 |

| P5 | M, 44 | Violin | 21 |

| P6 | F, 49 | Flute | 29 |

| P7 | F, 49 | Piano | 26 |

| P8 | M, 54 | Viola | 32 |

| P9 | F, 55 | Viola | 31 |

| P10 | F, 58 | Cello | 34 |

| P11 | M, 62 | Voice | 37 |

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Audience |

|

| Space |

|

| Co-creators |

|

| Performance Functions |

|

| Theme | Categories |

|---|---|

| Thrown into the Spotlight |

|

| The Role of a Mentor |

|

| Rise of the Professional |

|

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Self-Reflection |

|

| Possible Selves of the Music Performer |

|

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Skill-Acquired Performance Constituents |

|

| From Craftsmanship to Artistic Expression |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Šimunovič, N.; Habe, K. “You Know It, You Can Do It—Good Luck!”: Managing Music Performance Anxiety in the Context of Transforming Music Performance Ecosystems. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121696

Šimunovič N, Habe K. “You Know It, You Can Do It—Good Luck!”: Managing Music Performance Anxiety in the Context of Transforming Music Performance Ecosystems. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121696

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠimunovič, Natalija, and Katarina Habe. 2025. "“You Know It, You Can Do It—Good Luck!”: Managing Music Performance Anxiety in the Context of Transforming Music Performance Ecosystems" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121696

APA StyleŠimunovič, N., & Habe, K. (2025). “You Know It, You Can Do It—Good Luck!”: Managing Music Performance Anxiety in the Context of Transforming Music Performance Ecosystems. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1696. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121696