Mental Health Outcomes among Electricians and Plumbers in Ontario, Canada: Analysis of Burnout and Work-Related Factors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

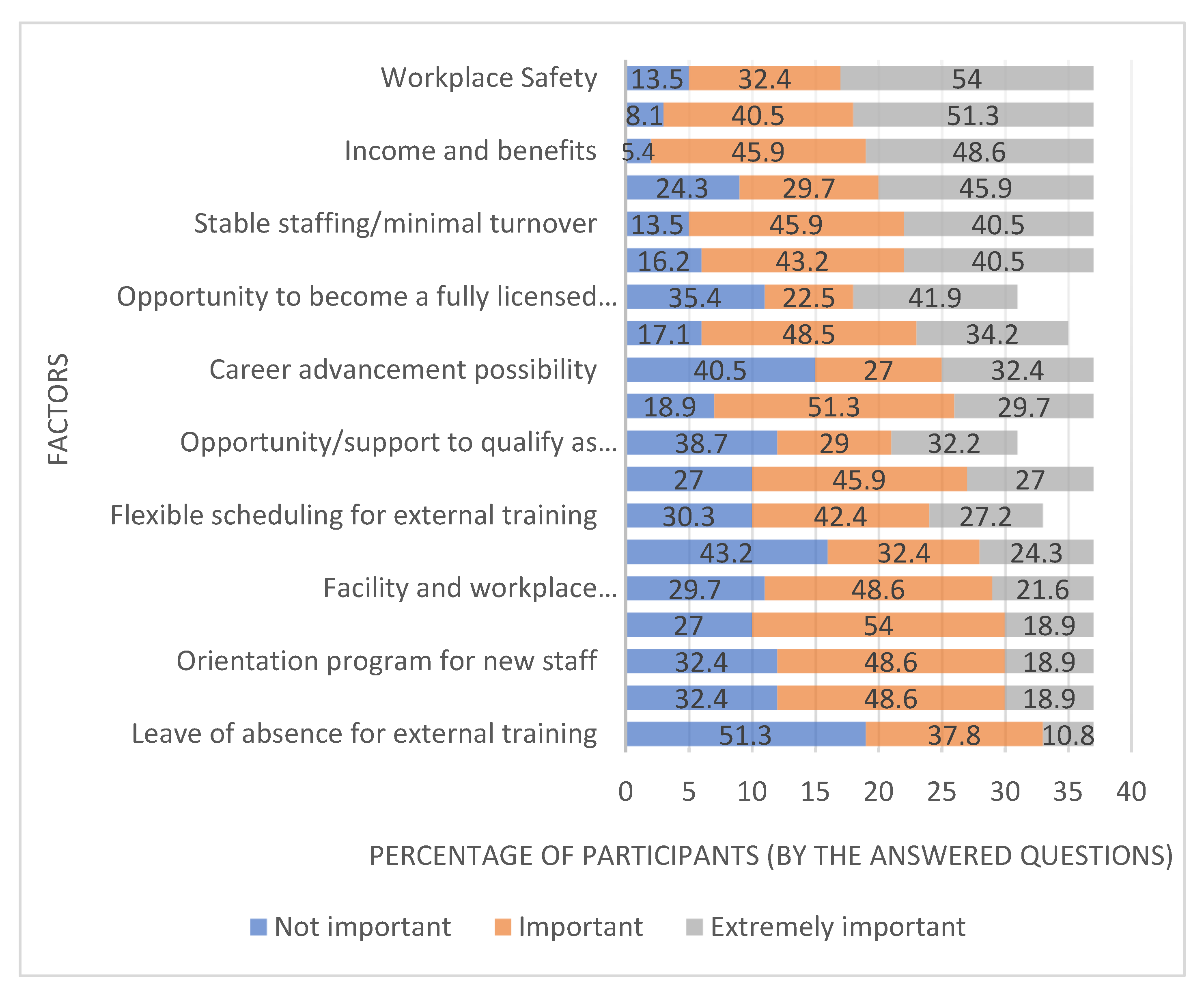

3.2. Importance of Work-Related Factors

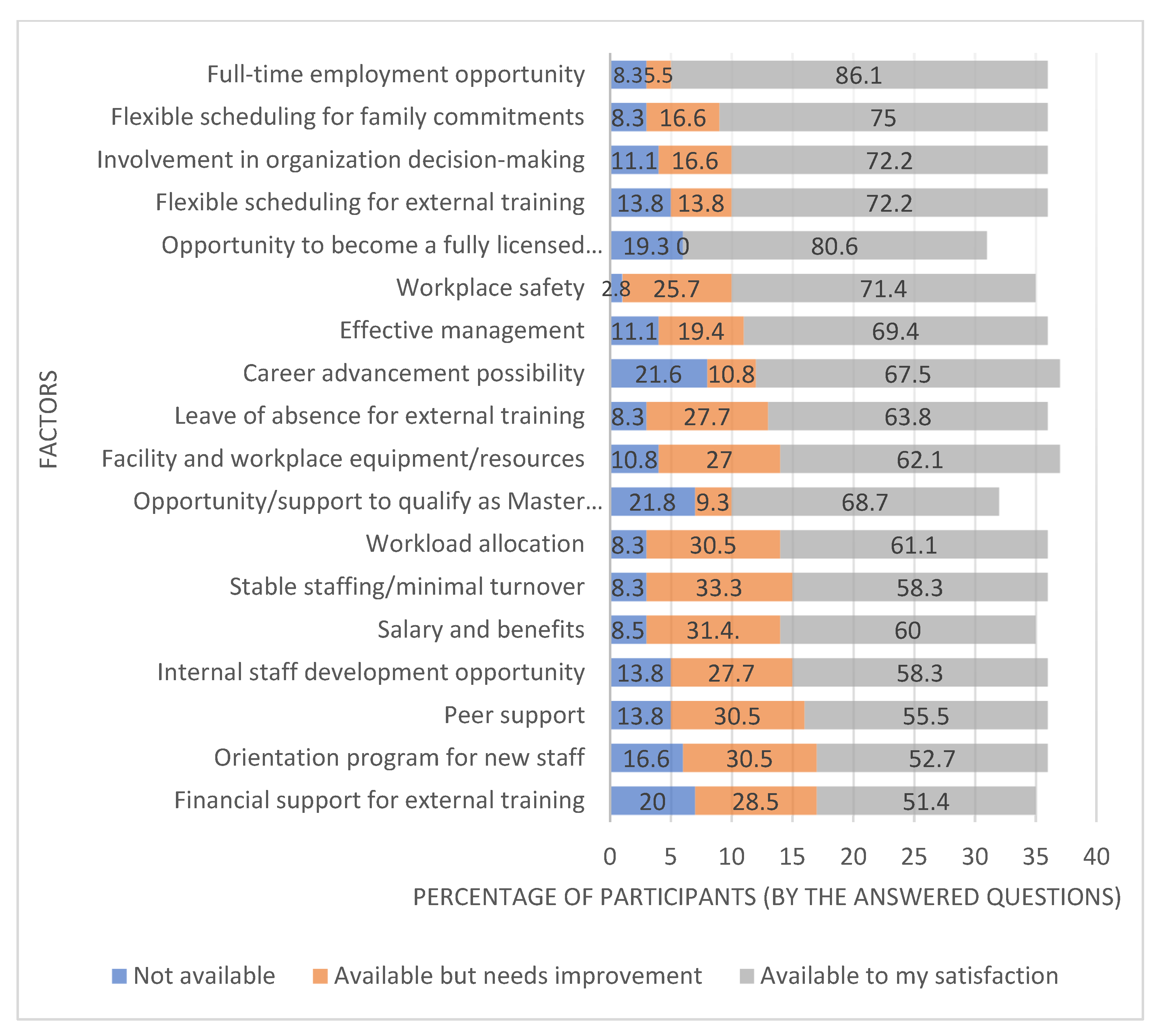

3.3. Availability and Satisfaction with the Work-Related Factors in the Current Workplace

3.4. Burnout

3.5. Association between Work-Related Factors and Burnout

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walsh, K.; Gordon, J.R. Creating an individual work identity. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2008, 18, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Ogbonnaya, C.; Känsälä, M.; Saari, E.; Isaksson, K. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work. Stress 2017, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Safe Work Australia. Australian Work Health and Safety Strategy 2012–2022. 2017. Available online: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-3062464922 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Anderson-Fennell, C. 83% of Construction Workers Have Experienced a Mental Health Issue. BC Building Trades. 2020. Available online: https://bcbuildingtrades.org/83-of-construction-workers-have-experienced-a-mental-health-issue/ (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Burki, T. Mental health in the construction industry. Lancet Psychiatry 2018, 5, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamardeen, I.; Loosemore, M. Suicide in the Construction Industry: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Undefined. 2016. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Suicide-in-the-construction-industry%3A-a-analysis-Kamardeen-Loosemore/f7ab0b62bfe227ba8d64cfaf64a3a3544bc915d6 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Milner, A.; Witt, K.; Burnside, L.; Wilson, C.; LaMontagne, A.D. Contact & connect—An intervention to reduce depression stigma and symptoms in construction workers: Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobsen, H.B.; Caban-Martinez, A.; Onyebeke, L.C.; Sorensen, G.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Reme, S.E. Construction Workers Struggle with a High Prevalence of Mental Distress, and This Is Associated With Their Pain and Injuries. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2013, 55, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stocks, S.J.; McNamee, R.; Carder, M.; Agius, R.M. The incidence of medically reported work-related ill health in the UK construction industry. Occup. Environ. Med. Lond Engl. 2010, 67, 574–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, V.; Caton, N.; Gullestrup, J.; Kõlves, K. A Longitudinal Assessment of Two Suicide Prevention Training Programs for the Construction Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnston, R.; Hogg, R.; Miller, K. Who is Most Vulnerable? Exploring Job Vulnerability, Social Distancing and Demand During COVID. Ir. J. Manag. 2021, 40, 100–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, K.; McCaffrey, R.J. Electrical Injury and Lightning Injury: A Review of Their Mechanisms and Neuropsychological, Psychiatric, and Neurological Sequelae. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2001, 11, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, C. Construction Workers and Addiction. Drug Rehab. 2020. Available online: https://www.drugrehab.com/addiction/construction-workers/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books, New York (1990) 381 pp (708 refs). Appl Ergon. 1992, 23, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Niedhammer, I.; Goldberg, M.; Leclerc, A.; Bugel, I.; David, S. Psychosocial factors at work and subsequent depressive symptoms in the Gazel cohort. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 1998, 24, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ramati, A.; Rubin, L.H.; Wicklund, A.; Pliskin, N.H.; Ammar, A.N.; Fink, J.W.; Bodnar, E.N.; Lee, R.C.; Cooper, M.A.; Kelley, K.M. Psychiatric morbidity following electrical injury and its effects on cognitive functioning. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2009, 31, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauter, S.L.; Lawrence, M.R.; Hurrell, J.J.; Lennart, L. Factores Psicosociales de Organización. Enciclopedia de Salud y Seguridad en el Trabajo; 1998. Available online: https://www.insst.es/documents/94886/162520/Cap%C3%ADtulo+34.+Factores+psicosociales+y+de+organización (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Scopinho, R.A. Privatização, reestruturação e mudanças nas condições de trabalho: O caso do setor de energia elétrica. Cad. Psicol. Soc. Trab. 2002, 5, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singerman, J.; Gomez, M.; Fish, J.S. Long-Term Sequelae of Low-Voltage Electrical Injury. J. Burn Care Res. 2008, 29, 773–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. We Shouldn’t Ignore Mental Health Issues in Plumbing and Heating. Condensate Pro. 2019. Available online: https://condensatepro.co.uk/blog/we-shouldnt-ignore-mental-health-issues-in-plumbing-and-heating/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Souza, S.F.; de Carvalho, F.M.; Araújo, T.M.; de Porto, L.A. Psychosocial factors of work and mental disorders in electricians. Rev. Saúde Pública 2010, 44, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomée, S.; Jakobsson, K. Life-changing or trivial: Electricians’ views about electrical accidents. Work Read Mass. 2018, 60, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, W. Construction Safety Includes Suicide Prevention—Constructconnect.com. Journal of Commerce. 2018. Available online: https://canada.constructconnect.com/joc/news/ohs/2018/10/construction-safety-includes-suicide-prevention (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- King, T.; Riccardi, L.; Milner, A. Suicide in the Construction Industry. Report submitted to MATES in Construction by The University of Melbourne. Volume V. 2022. Available online: https://mates.org.au/media/documents/Melb-Uni-Construction-Suicide-2001-2019-Vol-V-August-2022-40pp-A4-2.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Gullestrup, J.; Lequertier, B.; Martin, G. MATES in Construction: Impact of a Multimodal, Community-Based Program for Suicide Prevention in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 4180–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschman, J.S.; van der Molen, H.F.; Sluiter, J.K.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.W. Psychosocial work environment and mental health among construction workers. Appl. Ergon. 2013, 44, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulić, L.; Jovanović, J.; Galjak, M.; Krstović-Spremo, V.; Đurić, S.; Mirković, M.; Milosevic, L. The impact of occupational stress on work ability of electricians. Prax Medica 2019, 48, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Who is the Ontario Electrical League. Available online: https://www.joinoel.ca/whoweare (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Howe, A.S.; Lo, J.; Jaswal, S.; Bani-Fatemi, A.; Chattu, V.K.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B. Engaging Employers in Apprentice Training: Focus Group in-Sights from Small-to-Medium Sized Employers in Ontario, Canada; Restore Lab, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022; (under review). [Google Scholar]

- Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Rukholm, E.; Lariviã¨re, M.; Carter, L.; Koren, I.; Mian, O. An examination of retention factors among registered practical nurses in north-eastern Ontario, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2015, 15, 3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work. Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH Generic Job Stress Questionnaire. 2008. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/workorg/tools/pdfs/niosh-generic-job-stress-questionaire.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Aiello, E.N.; Fiabane, E.; Margheritti, S.; Magnone, S.; Bolognini, N.; Miglioretti, M.; Giorgi, I. Psychometric properties of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) in Italian Physicians. La Med. Del Lav. 2022, 113, e2022037. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, A.P.; Azuero, A.; Patrician, P.A. Psychometric properties of Copenhagen Burnout Inventory among nurses. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapa, T.; Carvalho, S.; Viana, J.; Ferreira, P.L.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Cabete, A.B. Development and Evaluation of a Global Burnout Index Derived from the Use of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in Portuguese Physicians. Acta Med. Port. 2018, 31, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Papaefstathiou, E.; Tsounis, A.; Malliarou, M.; Sarafis, P. Translation and validation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory amongst Greek doctors. Health Psychol. Res. 2019, 7, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thrush, C.R.; Gathright, M.M.; Atkinson, T.; Messias, E.L.; Guise, J.B. Psychometric Properties of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in an Academic Healthcare Institution Sample in the U.S. Evaluation Health Prof. 2021, 44, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadare, O.O.; Andreski, M.; Witry, M.J. Validation of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in Pharmacists. Innov. Pharm. 2021, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M.C.; Fischer, F.M. Stress at Work among Electric Utility Workers. Ind. Health 2009, 47, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. Managing Work-Life Balance in Construction; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; 368p. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J.; Lo, J.; Miller, P.; Mawren, D.; Jones, B. Psychological distress in remote mining and construction workers in Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2018, 208, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Mills, T.; Brian, K.; Lingard, H. Suicide in the construction industry: It’s time to talk. In Proceedings of the Joint CIB W099 and TG48 International Safety, Health, and People in Construction Conference, Cape Town, South Africa, 11–13 June 2017; pp. 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Greenglass, E.R. Introduction to special issue on burnout and health. Psychol. Health 2001, 16, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakare, J.; Omeje, H.O.; Yisa, M.A.; Orji, C.T.; Onyechi, K.C.N.; Eseadi, C.; Nwajiuba, C.A.; Anyaegbunam, E.N. Investigation of burnout syndrome among electrical and building technology undergraduate students in Nigeria. Medicine 2019, 98, e17581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meliá, J.L.; Becerril, M. Psychosocial sources of stress and burnout in the construction sector: A structural equation model. Psicothema 2007, 19, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada, S.C. The Canadian Immigrant Labour Market: Recent Trends from 2006 to 2017. 2018. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71-606-x/71-606-x2018001-eng.htm (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Todorovic, J.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Divjak, J.; Stamenkovic, Z.; Mandic-Rajcevic, S.; Kocic, S.; Ukropina, S.; Markovic, R.; Radulovic, O.; Arnaut, A.; et al. Validation of the Study Burnout Inventory and the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory for the use among medical students. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2021, 34, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javanshir, E.; Dianat, I.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. Psychometric properties of the Iranian version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory. Health Promot. Perspect. 2019, 9, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, J.E.; Brown, A.R.; Jones, A.E. Use of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory with Social Workers: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Hum. Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2018, 42, 437–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanzi, L.; Balducci, C.; Fraccaroli, F. Contributo alla validazione italiana del Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI). Psicol. Della Salut. 2013, 2, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperac, P.; Todorovic, J.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Maksimovic, A.; Karic, S.; Pilipovic, F.; Soldatovic, I. The Validity and Reliability of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory for Examination of Burnout among Preschool Teachers in Serbia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, F.L.R.; De Jesus, L.C.; Marziale, M.H.P.; Henriques, S.H.; Marôco, J.; Campos, J.A.D.B. Burnout syndrome in university professors and academic staff members: Psychometric properties of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory–Brazilian version. Psicol. Reflexão E Crítica 2020, 33, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 47.97 | 15.62 | |

| Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | ||

| Born and/or raised in Ontario | Yes | 35 | 87.5 |

| No | 5 | 12.5 | |

| Marital Status | Married/Common-law | 32 | 80.0 |

| Single | 6 | 15.0 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Education Level | Completed high school | 11 | 27.5 |

| College certificate/diploma | 22 | 55.0 | |

| University Undergraduate and graduate | 4 | 10.0 | |

| Other | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Training obtained in Ontario | Yes | 39 | 97.5 |

| No | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Primary language | English | 36 | 90.0 |

| French | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Spanish | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Ukrainian | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Romanian | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Ethnicity | White North American | 29 | 74.3 |

| White European | 6 | 15.4 | |

| Other | 2 | 5.1 | |

| Asian East | 1 | 2.6 | |

| Aboriginal | 1 | 2.6 | |

| Smoking | Non-smoker | 27 | 67.5 |

| smoker | 13 | 32.5 | |

| Current employment | Employed in electrical sector | 37 | 92.5 |

| Employed in plumbing sector | 2 | 5.0 | |

| Employed in non-electrical/plumbing sector | 1 | 2.5 | |

| Belong to a Union | No | 37 | 92.5 |

| Yes | 3 | 7.5 | |

| Average overtime hours per week | None | 21 | 60.0 |

| 5 h or less | 5 | 14.3 | |

| 6–10 h | 7 | 20.0 | |

| More than 10 h | 2 | 5.7 | |

| Intend to stay in current position for the next 5 years * | Yes | 31 | 94.0 |

| No | 2 | 6.0 | |

| Gross annual income | Less than $80,000 | 13 | 32.5 |

| $80,000 or more | 19 | 47.5 | |

| Prefer not to answer | 8 | 20.0 | |

| Type of Burnout | Mean [SD] | Minimum Score | Maximum Score | Median | Moderate Burnout (n) | High Burnout (n) | Severe Burnout (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal burnout | 33.48 [16.60] | 4.16 | 70.83 | 33.33 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Work-related burnout | 25.63 [13.21] | 7.14 | 67.85 | 21.42 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Colleague-related burnout | 17.56 [16.32] | 0.00 | 54.16 | 16.66 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bani-Fatemi, A.; Sanches, M.; Howe, A.S.; Lo, J.; Jaswal, S.; Chattu, V.K.; Nowrouzi-Kia, B. Mental Health Outcomes among Electricians and Plumbers in Ontario, Canada: Analysis of Burnout and Work-Related Factors. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120505

Bani-Fatemi A, Sanches M, Howe AS, Lo J, Jaswal S, Chattu VK, Nowrouzi-Kia B. Mental Health Outcomes among Electricians and Plumbers in Ontario, Canada: Analysis of Burnout and Work-Related Factors. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(12):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120505

Chicago/Turabian StyleBani-Fatemi, Ali, Marcos Sanches, Aaron S. Howe, Joyce Lo, Sharan Jaswal, Vijay Kumar Chattu, and Behdin Nowrouzi-Kia. 2022. "Mental Health Outcomes among Electricians and Plumbers in Ontario, Canada: Analysis of Burnout and Work-Related Factors" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 12: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12120505