1. Introduction

Geotourism is an increasing business in modern society. Geotourism is a knowledge-based type of tourism that looks for an interdisciplinary integration of the tourism industry with the conservation and interpretation of geological heritage at the same time as it promotes the economic and social development of local communities [

1,

2,

3]. In this sense, it is considered a sustainable type of tourism that lies at the intersection between tourism as a global phenomenon and sustainable development as a global task [

4,

5,

6,

7].

One particular type of geotourism is “Volcano Tourism” [

8,

9,

10,

11], as volcanoes and volcanic terrains have a worldwide fascination and many are visited by huge numbers of people each year (e.g., Iceland, Canary Islands, Hawaii, Yellowstone, Etna, and Vesuvius). These visits to both live and extinct volcanic landscapes provide much public recreation, adventure, and enjoyment. They also afford opportunities to observe, learn, and appreciate the power and role of volcanism in building the planet’s surface.

The benefits of geotourism can be measured through environmental, social, and economic indicators, such as increased natural heritage conservation, improved social benefits like self-esteem, jobs, and incomes [

1,

2,

3]. Since geotourism adds values to local or regional communities, it economically supports geological heritage conservation [

2]. Consequently, there is a need to gain a greater understanding of the nature and characteristics of geotourism, especially in relation to the importance of placing geology at the center of a destination, but also in regard to its characteristics, impacts, and management.

Most protected volcanic areas have generated exciting tourism products and opportunities for public use, which provide substantial community benefits. Several studies have proposed guidelines for planning and managing sustainable tourism in protected areas [

12,

13] and a few of them include the analysis of revenue sharing in such areas [

14,

15]. However, we still need to estimate the benefits of tourism in many protected volcanic areas and how to maintain and increase this business in a manageable and sustainable way. Unfortunately, due to the relatively early stages of volcano tourism, there are still very few data compilations concerning the exploitation and benefits from volcano tourism (e.g., [

14,

15]). Therefore, many more case studies need to the analyzed in order to quantify and evaluate this tourism sector in-depth and propose innovative products that could guaranty the sustainability of volcano tourism.

The natural park of La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone is an area of great geological, botanical, faunistic, and landscape value and, although it is an area with considerable human activity, its landscape and unique natural environment have been well-preserved [

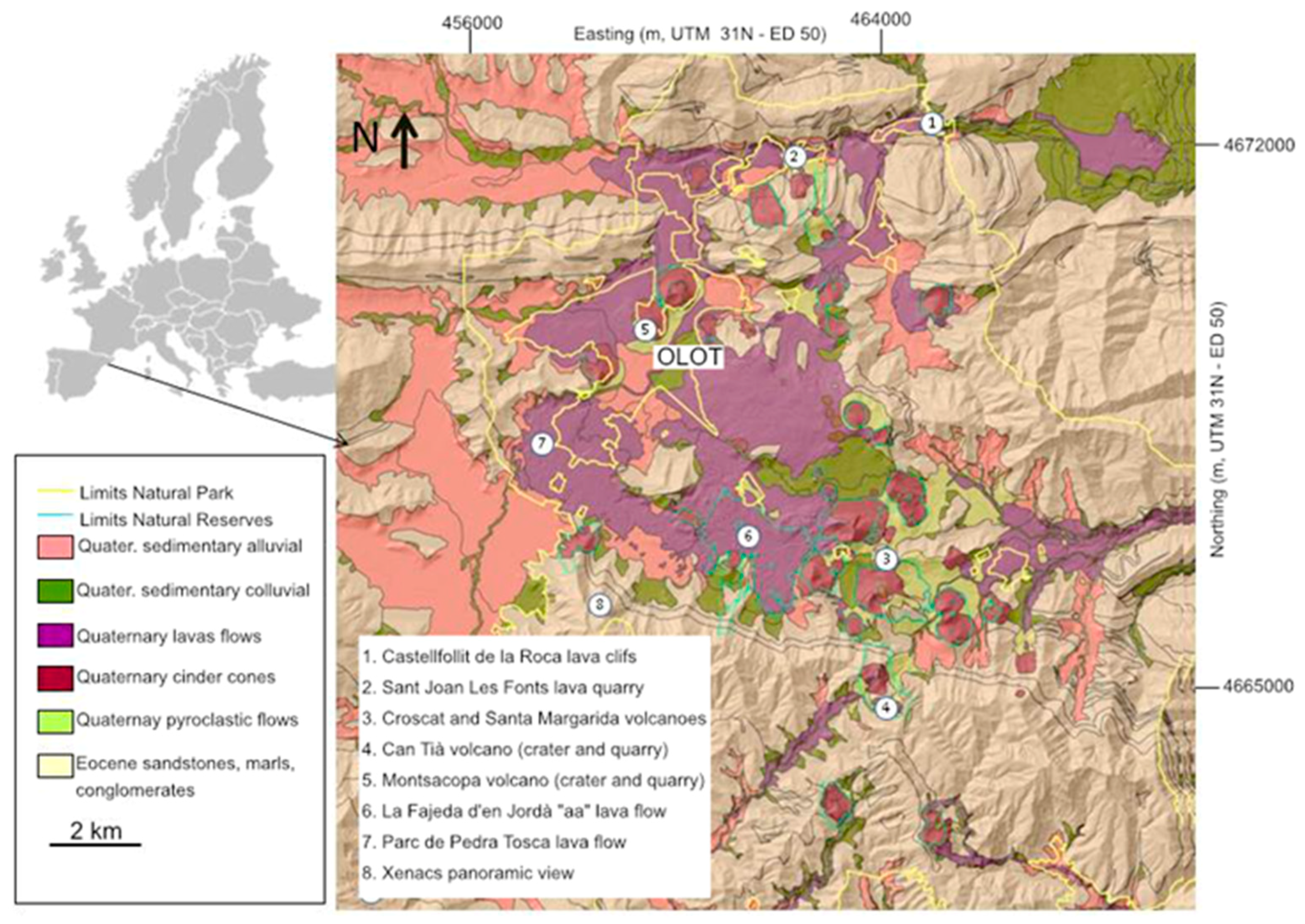

16] (

Figure 1). This protected area includes the northern side of the La Garrotxa monogenetic volcanic field, which contains about 50 well-preserved volcanic cones that exhibit a large diversity of strombolian and phreatomagmatic volcanic products (

Figure 1) [

17,

18]. The volcanic activity and humid climate characteristic of this area gave rise to the fertile soils [

19] that provide the area with excellent biodiversity.

Since its declaration as a natural park in 1982, but particularly since 1986, when an administration team took responsibility for its management, this area has become an important lure for local, national, and foreign tourism, transforming this poorly known territory into one of the best known and most visited geosites of Catalonia. As an example of volcano tourism that has been exploited in a sustainable way, in this study, we describe how La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone was protected in a natural park and how the different actions taken under this protection contributed to a sustainable geotourism that has led to important socio-economic benefits for the region. This is a particular case study that, together with the others that already exist, will contribute to a better understanding of the possible benefits and threats of volcano tourism.

2. Geographic and Geological Setting

Geologically, La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone is one of the best-preserved volcanic regions in the Iberian Peninsula from those pertaining to the Neogene–Quaternary basaltic volcanism of the European rifts system [

17,

18,

20] (

Figure 1), with intense human activity, which at times, impedes the conservation of the land. Volcanic activity began some 700,000 years ago in La Garrotxa [

20], and continued until the early Holocene with the eruption of the Croscat volcano about 10,000 years ago [

21]. In total, at least 50 eruptions have been identified [

2,

3], leading to volcanic cinder and spatter cones, maars and tuff rings, as well as several lava flows that filled the valleys in the area. The stratigraphic, structural, and hydrogeological characteristics of the substrate above which these volcanoes were emplaced favored phreatomagmatic activity, which combined with the magmatic Strombolian activity, caused a large variety of eruption sequences [

17,

18].

The richness of volcanic soils and the climate is one of the other determining factors in the zone, where the Mediterranean climate, characterized by mild winters and hot summers with low rainfall, mixes with the Atlantic climate, where rain and temperature inversion is abundant in summer; whereas in winter, this inversion causes lower temperatures and frequent frost. The diverse relief, the confluence of the Mediterranean and Atlantic climates, and the diversity of substrates lead to a great variety of plant species and also to a wide variety of natural environments, which has allowed a very diverse and interesting faunistic population to exist, characterized by the cohabitation of typical Mediterranean fauna with typically Central European species [

22].

The landscape, shaped by volcanic activity, geomorphological agents, and humans, is one of the most distinctive features of this area. For many centuries, human presence was associated with the exploitation of agricultural, livestock, and forest resources, and the landscape became a harmonious mosaic of fields, pasture, and woodland that supported the family economy. The craft and industrial activity contributed towards great social and landscape change.

3. History of the Protection of the Zone

The urban and industrial growth of the 1960s led to a number of serious environmental problems: extraction of volcanic tephra, urban growth that did not respect the environment, river pollution, and the proliferation of uncontrolled dumping. The combination of all these problems posed a serious threat to the natural assets. The need to protect this natural space triggered a series of sociocultural movements that culminated when the parliament of Catalonia, in 1982, passed the law to protect La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone, converting it into a natural park. The goal was to protect its geological, botanical, and landscape assets, and to combine the conservation of the zone with its economic development. Currently, this protected space covers 15,308 ha, where more than 40,000 inhabitants are distributed across 11 towns, and includes 28 nature reserves.

The mining exploitation of the Croscat volcano (

Figure 2) served as a springboard for demands for the conservation of the natural heritage and the volcanoes in the area. Its history ties in very much with the geotourism that began to be promoted in the area after the declaration of the natural park of La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone.

Table 1 summarizes the activities and actions taken before and after the declaration of the natural park.

4. Tourism Resources in the Area

La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone is the only zone for volcanic geotourism with well-preserved volcanoes located in the center of the Pyrenees–Mediterranean Euroregion, which encompasses the French region of Occitanie, and the autonomous regions of Catalonia and Aragon in Spain. This Euroregion has a population of 14,529,912 over a distance of less than 300 km. This is the potential audience visiting these volcanoes, since it is a unique destination. The area has different places of geographical interest, with natural and cultural resources, which complement each other perfectly and determine the attractiveness of the zone.

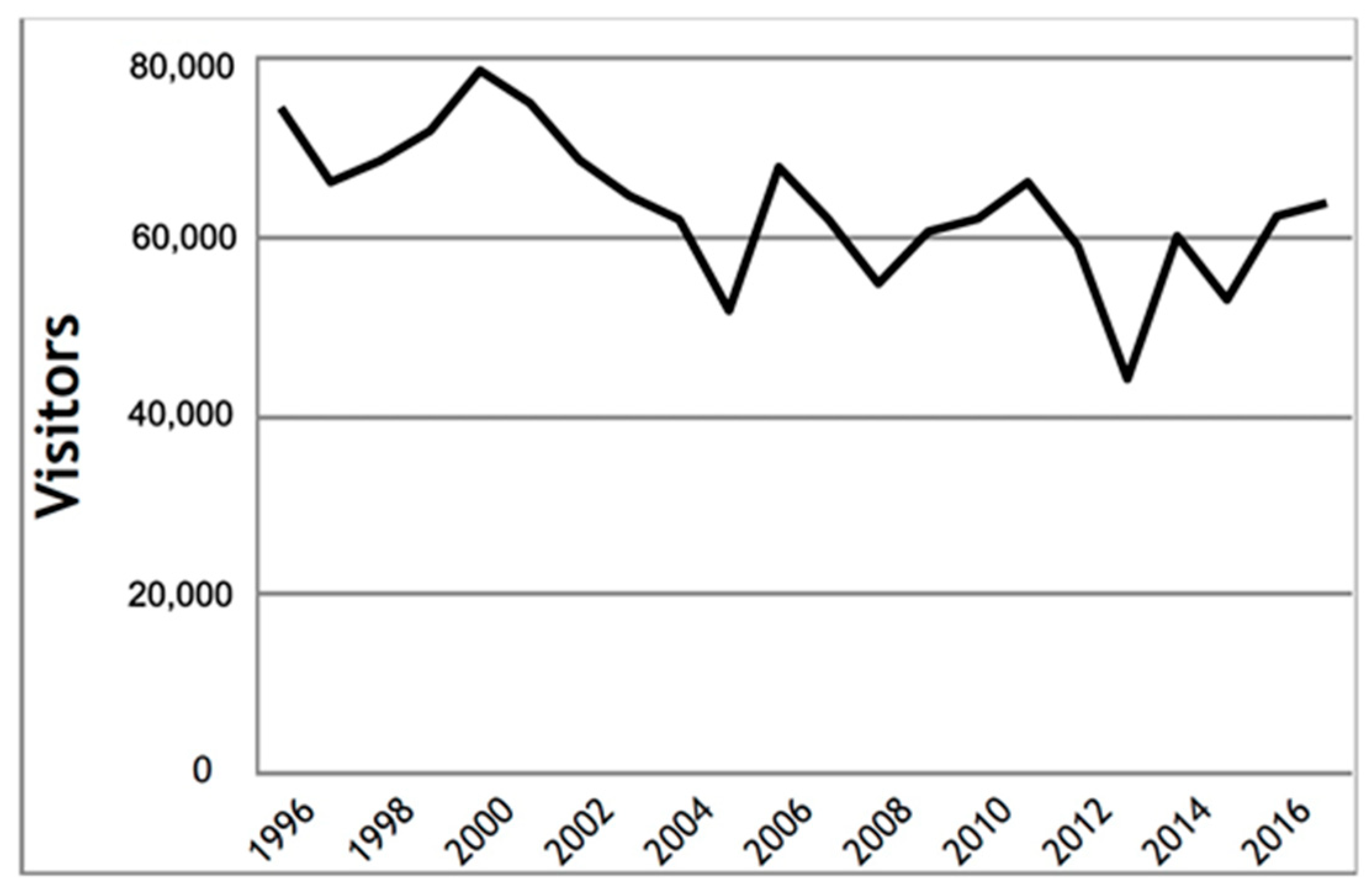

According to the statistics provided by the natural park, in 2010, La Garrotxa region received 355,735 visitors, which is 53,000 more than in 2001 [

23] (

Figure 3). Of these visitors, 48% were families and 37% were couples, 81% were Catalans (i.e., local tourism), and 76% of the visitors came to see the volcanoes [

23].

4.1. Outcrops and Places of Geological Interest

La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone displays several places of geological interest, from which eight are remarkable [

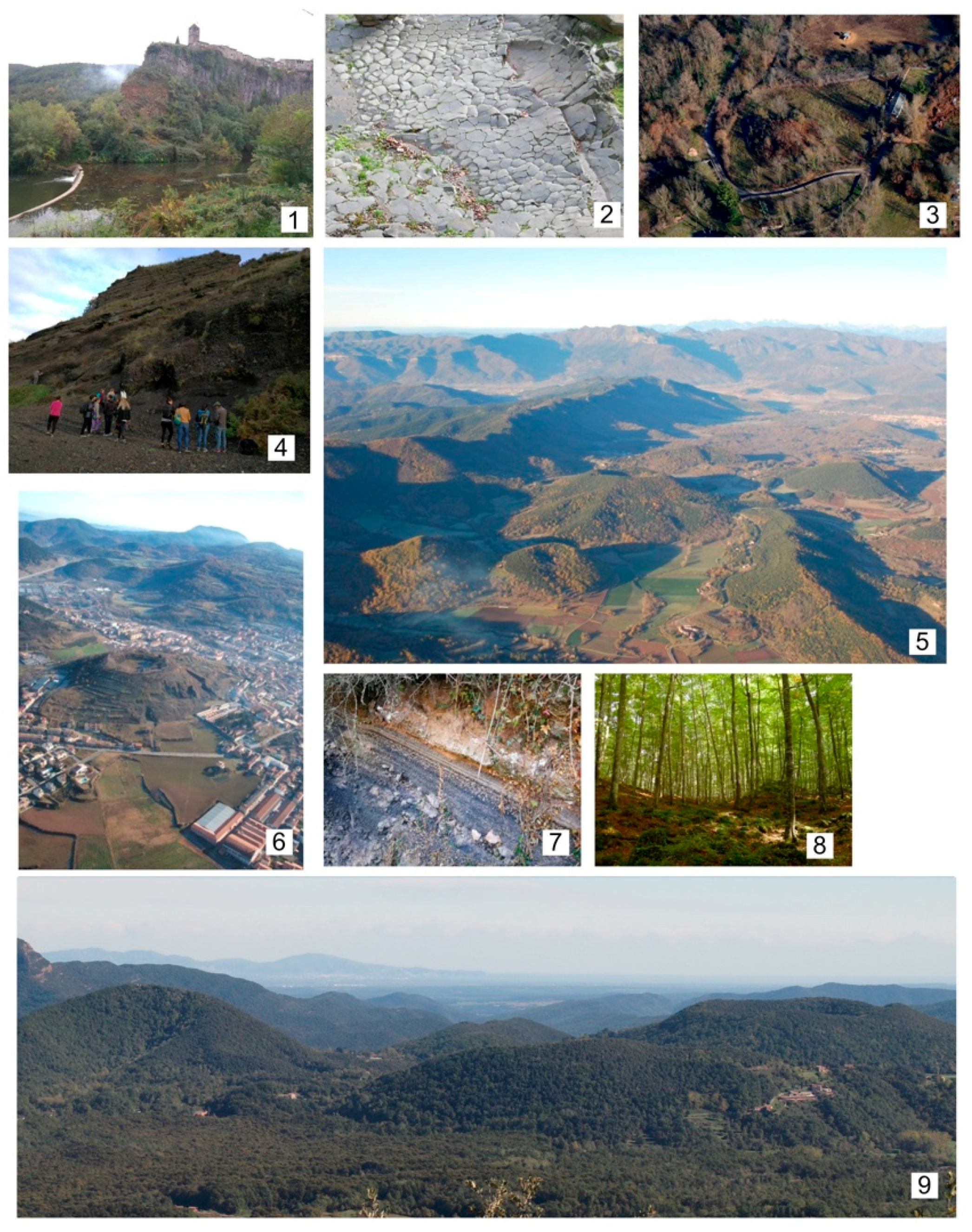

25] (

Figure 1 and

Figure 4). (1) To the north of the zone stands the lava flow cliff of Castellfollit de la Roca, where the town is perched on top of a 50-m crag of basalt columns. (2) Nearby are the former quarries of Sant Joan les Fonts, where different lava flows with different internal morphologies (e.g., columnar joints, tumuli, etc.) can be observed. (3) The most recent volcanic activity is located in the center of the volcanic zone, with easy access to the cinder cone of the Croscat volcano, to the Santa Margarida maar-type crater and its deposits, to the tephra quarry of the Croscat volcano, and to the Rocanegra volcano. (4) Another place of geological interest is the Can Tià volcano, its maar-type crater, and the outcrop that corresponds to an old quarry, which shows the full stratigraphic succession of this volcano. (5) The Montsacopa volcano in Olot, a route that reveals a cinder cone with a circular crater at the top and an interesting route through its tephra pits that serve to interpret the formation of the volcano. (6) The Jordà beech forest is a geological, natural, and cultural asset that leads visitors through the well-preserved “aa” type lava flow from the Croscat eruption; this type of beech forest is unusual at this latitude, as it is more common in Atlantic climates than Mediterranean ones [

19], and has served as a source of inspiration to poets and painters alike. (7) The Pedra Tosca Park in the Tosca Forest is another place located at the top of a lava flow; in this case, from the Puig Jordà volcano. This is a place of geological interest due to the large number of rootless spatter cones that can be observed on this lava, but also of cultural interest for the dry-stone constructions, shelters, and land clearing present. (8) The last main place of geological interest is the Xenacs viewpoint where the zone’s landscape and relief can be contemplated and understood, as well as the location of the volcanoes.

4.2. Other Places of Natural and Cultural Interest

In addition, this volcanic area has several places of cultural, natural, and intangible interest [

26] (

Figure 5), from which the following seven are the most remarkable. (1) In Olot, we find the Parc Nou-Moixina, a place that holds the last pockets of English oak in the Olot valleys, a humid area, as well as the Volcano Museum. (2) Olot’s old quarter and its modernist architecture built during the industrial growth of the 18th century are also notable. (3) The Colltort Castle between Santa Pau and Olot is a place to observe volcanic cones, craters, and landscape, and is a prime example of the 15th-century Rebellion of the Remences, the first peasant revolution to occur in Europe. (4) Santa Pau is a town built around a castle during the 13th and 14th centuries, with an arcaded square where a market was held. (5) Besalú, the former capital of the region, is a town with excellently preserved ancient medieval buildings, an impressive bridge, squares,

miqwe jueu (baths), and churches and monasteries. (6) The town of Sant Feliu de Pallerols is one of the finest examples of a medieval town with a holy space. (7) Finally, the intangible value of the gastronomy based on natural products, such as local beans, meat, and cured cold cuts, is falling under what is locally known as volcanic cuisine.

4.3. Tourism Interpretation Centres

During the creation of the natural park, a series of centers were established to disseminate the information of the main values of the park among the visitors. The management and number of these tourism centers has fluctuated over the past 30 years according to the conservation policies of the natural environment (

Table 1). The natural park has created four centers for visitors: The Casal dels Volcans, at the Parc Nou-Moixina in Olot; Can Serra, at the entrance of the nature reserve of the Jordà beech forest, on the road to Santa Pau; Can Passavent, at the entrance of the nature reserve of the Croscat volcano; and the Sant Feliu de Pallerols station, which only operated as a center for the park for three years. The goal of these centers is to inform and educate visitors about both the zone and respecting the natural heritage. In recent years, the centers have been attended by more than 1,500,000 visitors, with an average of 65,000 visitors per year from the more than 300,000 who visit the park, which means that 1/5 of the total visitors of the park per year are informed, according to the statistics provided by the natural park.

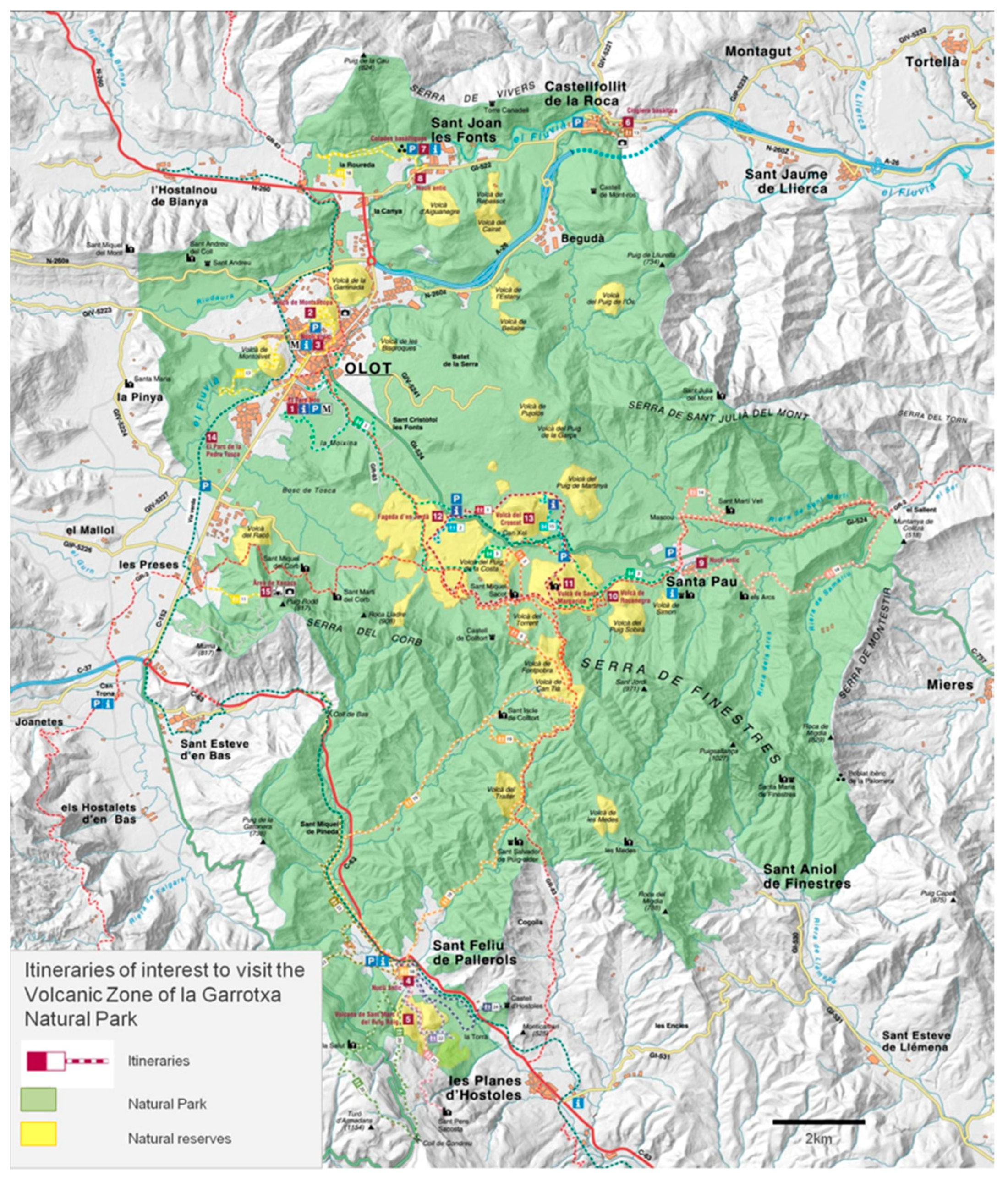

4.4. Itineraries to Visit the Volcanoes

The volcanic zone has 25 itineraries of varying durations, from as short as 30 min (the Joan Maragall itinerary to the Jordà beech forest) to longer ones such as itinerary 19 to visit the Can Tià and Fontpobre volcanoes, which takes five hours (

Figure 6). Some of these itineraries, such as the Joan Maragall route, have overcrowding issues in the autumn and Easter, with an average of 2025 visitors per day, according to the statistics provided by the natural park in 2015. For another itinerary, the one that takes visitors to the Croscat volcano tephra quarry (itinerary 15), the number of visitors that attended in the same year in the Can Passavent information center was 37,614, of whom almost half, 15,971, were school groups, as indicated by the Natural Park.

4.5. Outreach

In order to help visitors to understand the existing volcanic activity, several outreach products have been published with the goal of highlighting the interest of the zone for visitors, and to encourage visits that visit for more than one day. Among these outreach products, the “Field Guide of the La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone” [

27] (

Figure 7) documents how to observe and interpret the volcanic activity of this zone from twelve places of geological interest. Moreover, the volcanological map of La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone Natural Park [

28] complements this guide and helps visitors to discover the volcanoes on every itinerary or in every place. In the information centers, visitors are provided with maps to visit the different places that are considered the most representative of the natural park.

4.6. Education and Training

Education is one of the essential strategic lines employed to preserve protected natural spaces [

29]. Educational programs developed in the natural park of La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone are aimed at raising awareness among the population and visitors about the environment and volcanic activity through the assimilation of contents necessary to obtain skills, abilities, and the desire to participate in the prevention and solution of environmental problems. For this reason, the level of knowledge on the volcanological values of those people who live near the volcanoes and of those who visit them is important. Therefore, programs are required for both the local population and for visitors. Local residents need to understand volcanic activity and how to transmit their values to visitors, and as such, it is important to train all related workers in activities directly or indirectly related to tourism. A particular effort is made in training guides who take visitors to La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone, both through school groups and adult visitors. Approximately 60,000 schoolchildren visit the zone each year, and in effect, they constitute one of the main channels for the dissemination of the natural geological values and to increase awareness about their conservation. Therefore, we can say that since 1994, more than 1,500,000 students have visited the volcanoes of La Garrotxa, thus becoming a very significant figure that represents the majority of the school-aged Catalan population [

29].

5. European Charter for Sustainable Tourism

La Garrotxa volcanic zone attempts to achieve sustainable tourism through the European charter for sustainable tourism (ECST) [

30]. Through its principles and phases, this charter structures a strategy of sustainable local development. La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone was one of the first natural parks to carry out a pilot test in 2000 aimed at:

Fostering the knowledge and support of protected natural spaces, which represent a fundamental part of our natural and cultural heritage, and which therefore must be conserved for the enjoyment of current and future generations.

Orienting the management and tourism development of the protected spaces around sustainability, that is to say, making the conservation of the land’s assets compatible with the satisfaction of private sector aspirations, the expectations of visitors, and the needs of the local population.

Initially, the natural park and the local governments undertook work according to the 10 principles established by the ECST:

To involve all parties related to tourism in the protected space and the surrounding areas in the development and management of the protected area.

To prepare and implement a sustainable tourism strategy and action plan for the protected area.

To protect and enhance the area’s natural and cultural heritage, for and through tourism, and to protect it from excessive tourism development.

To provide all visitors with a high-quality experience in all aspects of their visit.

To provide visitors with adequate information about the special qualities of the zone.

To promote specific tourism products which help visitors to discover and understand the area.

To increase knowledge of the protected area and of sustainability issues amongst all those involved in tourism.

To ensure that tourism improves, and does not reduce, the quality of life of the local population.

To increase the profits derived from tourism for the local economy.

To control and monitor the flow of visitors to reduce their potential negative impact.

Later, in a second phase, a total of 18 companies from the private sector joined the charter and participated in the co-management of the natural park. As the main positive impacts, these companies highlighted: (i) the improvement of the relations and communication with the team managing the protected space; (ii) the collaboration with other companies associated with the ECST; (iii) the improvement in clients’ behavior in the use of resource saving and efficiency based on information provided by the companies during the adhesion process; and (iv) encouragement of the support and promotion of local products and services associated with the tourism agri-food sector, crafts, etc.

One of the star products of the ECST is the network of itineraries called Itinerannia, which provides different itineraries for visiting and enjoying the landscape and natural values, such as the deposits and morphologies of the volcanic activity in the zone. In 2014, according to Turisme Garrotxa [

31], the network received 67,850 walkers and an economic impact of 3,263,000.00 €.

6. Threats to the Conservation of the Natural and Social Assets Due to Tourism

The main problems that the increase of geotourism in areas such La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone encompasses are mainly related to the possibility of developing tourism based on short, low-quality visits, concentrated in time and space, and with serious overcrowding problems, causing a collapse of services and significantly lowering the quality of the visits.

In view of this situation, protected areas call for the need to manage, channel, and shape the affluence of visitors whilst respecting their traditional missions (i.e., the conservation and development of the territory). In the particular case of La Garrotxa, there are essentially three impacts and threats that are incompatible with the promotion of tourism: overcrowding, sustainable mobility and disparity in management policies, and cuts in the protected natural spaces applied in 2010.

The overcrowding in the zone occurs in the autumn, coinciding with visits to the beech forest to admire the red tones of trees and the volcanoes, especially the Jordà beech forest. For example, some 700 m in length of Itinerary 2 can be walked by 2025 visitors in one single day [

32]. These are concentrated between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m., causing mobility problems and concerns with neighbors, in addition to effects on the environment. The goal is to be able to regulate this intensity of visitors through car parks, the payment of entrance fees, and future actions to promote sustainable mobility in the area, avoiding access with personal vehicles.

Since La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone became a natural park, the commitment from the administration responsible for the conservation of the natural heritage has been inconsistent, and the policy and management of nature has gone through different stages and periods [

33], which reveal diverse sensitivities in relation to the way it is considered (social relevance) and managed (resources, strategies and instruments). Each phase has been characterized by common elements in governance (dividing responsibilities, tensions between administrations and governments, public–private relations, etc.). In turn, these phases have been subdivided into periods that define and characterize the action of the successive governments. The Natural Park has not been left unaffected by these occurrences (

Table 1) and has seen its management and good reputation for conserving the geological heritage endangered. The reduction in the budget by half suffered in recent years due to the global economic crisis, represents a serious problem for the area. This has clear implications, although these have been mitigated through a key factor, which is the administrations’ and local entities’ participation in the co-management of the natural park (

Table 2 and

Figure 8).

7. Socio-Economic Impact

The number of people who, for different reasons, are interested in discovering these spaces that have been given special protection, is increasing every day. In Catalonia, for example, approximately 5.1 million people visited the different protected areas located in its territory in 2012, and 5.5 million visited in 2013 [

24]. This means that a new economic activity has been developing alongside this type of tourism activity. At the same time, the protected natural areas act as ecosystem services, which are those services that people receive from ecosystems and that maintain, directly or indirectly, their quality of life [

34].

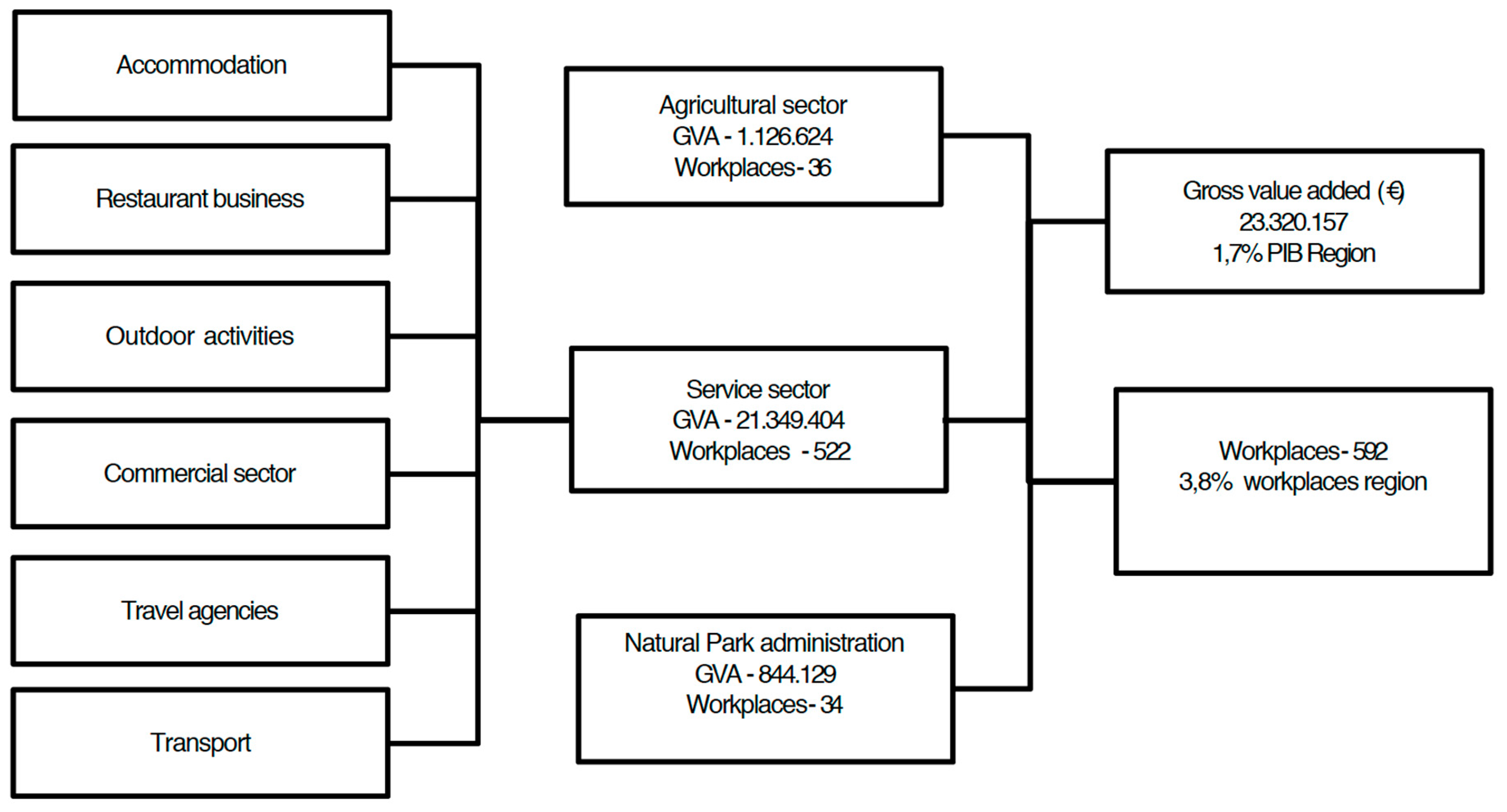

As regards the economic value, its profit is clear according to Institut Cerdà 2015 [

24] (

Table 2). Despite the recession that affected Catalonia during the recent economic world crisis, for every 1 € that the administration has invested in the natural park of La Garrotxa, the return for the zone has been 8.8 €. The economic impact of this protected space exceeds that produced by some of the country’s top tourism attractions. For example, it represents more than double the economic impact generated by the Dalí Museum and the Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation [

24]. In the case of the volcanoes in La Garrotxa, this economic impact represents a total of €23,320,157 of annual gross added value (

Table 2), which is equivalent to 1.7% of the gross value added (GVA) of the entire Garrotxa region. But the balance is also positive in employment since, directly or indirectly, the preservation and good management of the volcanoes in the zone has led to the creation of 592 jobs, representing 3.8% of La Garrotxa employment [

24] (

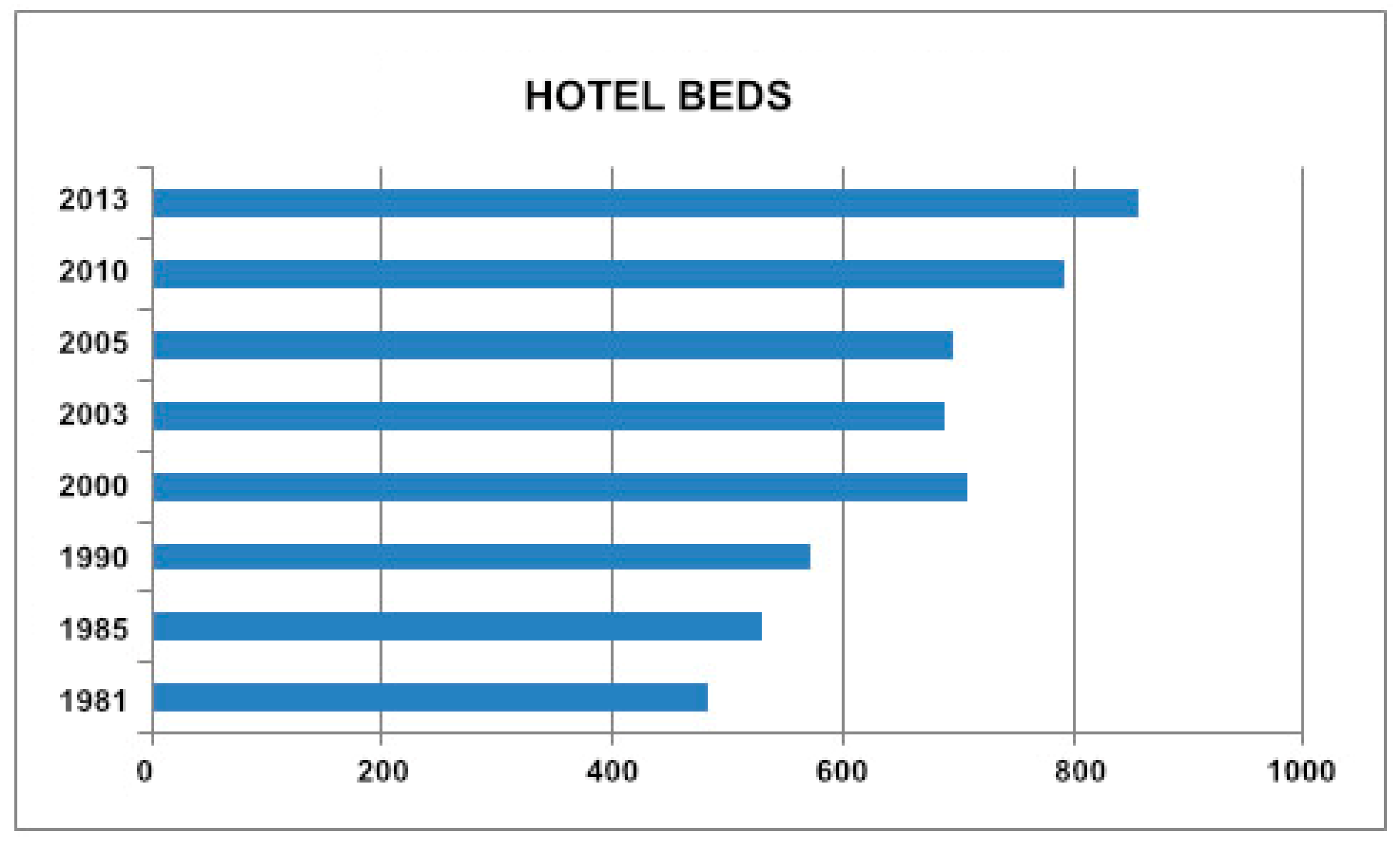

Figure 8). The difference in the benefits obtained from the same volcanic zone when comparing a mining extraction that had four or five workers and conservation is clear, since benefits related to the second option have multiplied by ten. Moreover, another clear indicator of this economic benefit and the creation of jobs is that since the creation of the natural park, the offer of hotel beds has doubled in the area (

Figure 9), thus supporting the fact that an efficient management of geological heritage is a suitable tool for sustainable tourism [

8,

9].

8. Discussion and Conclusions

The innovation of our research is to provide a clear description and quantification of the main benefits and threats that volcano tourism can represent for a particular protected area, thereby contributing to the improvement of scientific research and sustainable tourism. The natural park of La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone is a good example of how sustainable tourism represents a considerable benefit when efficient management is applied to geological heritage. From its creation in 1982 to the present day, the natural values have been preserved and this has implied a positive social and economic impact.

La Garrotxa Volcanic Zone clearly demonstrates that using geo-conservation as a tool for sustainable tourism is a good strategy to follow. If well-managed, it brings economic and social improvements to the area, not only in tourism, but also in the global image of the territory. This good image that the territory exports can be seen in the logos used by local companies and entities, as most of them show a clear reference to the volcanoes.

The positive social and economic impact that geotourism has had in La Garrotxa is based on different essential factors. One of these has been the scientific knowledge of the area. High-quality scientific research about La Garrotxa volcanoes has been important in assessing the best places to be promoted and providing correct and rigorous information to visitors. For this reason, cartography, guides, and data bases built in a suitable geographic information system have been essential. Another important aspect has been the involvement and co-management of local actors such as town councils and public and private entities. In this way, changes in environmental policies and budget cuts by the Catalan government (

Table 2) can be overcome. The involvement of these actors means that there has been effective pressure to revert possible cuts and to become involved in management deficits. A better co-management of the area is still required in order to make progress in the conservation of the volcanoes, alongside the social and economic improvement that geotourism entails. This has been the key to be able to transmit the importance of the zone to visitors, to be able to generate a critical spirit in order to continue generating sustainability policies, and to prevent tourism from having serious ecological and social impacts. In this sense, the training and education programs that have been carried out for decades in La Garrotxa have been significant, which should be maintained in the future as a guarantee for its preservation and sustainable management.

The experience acquired at La Garrotxa can be exported to other protected areas with similar characteristics and potential problems. Looking at current trends in tourism, it is obvious that geotourism and volcano tourism will continue to grow. Therefore, it is important to prevent the potential problems this may cause. Despite the fact that each particular area may have different characteristics and, consequently, may undergo different problems related to geotourism, these may not differ so much from those identified in La Garrotxa. Hence, the same solutions applied here are recommended for other areas, in particular the application of revenue sharing and public and private investment to guarantee undertaking scientific research that can ensure a good knowledge of the natural values of the area, as well as the establishment of good training and education programs aimed at local populations and visitors in order to raise awareness about them.