Abstract

Infectious Bursal Disease (IBD) is an immunosuppressive viral disease caused by the Infectious Bursal Disease Virus (IBDV). It primarily affects young chickens, targeting the bursa of Fabricius, and poses significant economic threats to the poultry industry. To date, in addition to strict biosecurity measures, large-scale immunization is the optimal strategy and effective method to prevent and control IBDV infection. The emergence of new variant strains has made it more urgent to develop new vaccination strategies against IBD. Over the past few decades, many high-quality vaccines have been available on the market for the control of IBD, which can provide solid protection against the infections and diseases caused by classic IBDV to very virulent IBDV that had been continuously evolving and were endemic worldwide. However, viruses are not static. As they continue to circulate and evolve in the fields, novel antigenic variant viruses have been emerged in the last few years, and vaccines need to keep up with their pace. Collectively, this review summarizes the strategic evolution of IBDV vaccines from traditional methods to cutting-edge molecular platforms, providing promising strategies for developing the next-generation vaccines with higher safety, efficacy, and the ability to keep pace with the antigenic drift in IBDV.

1. Introduction

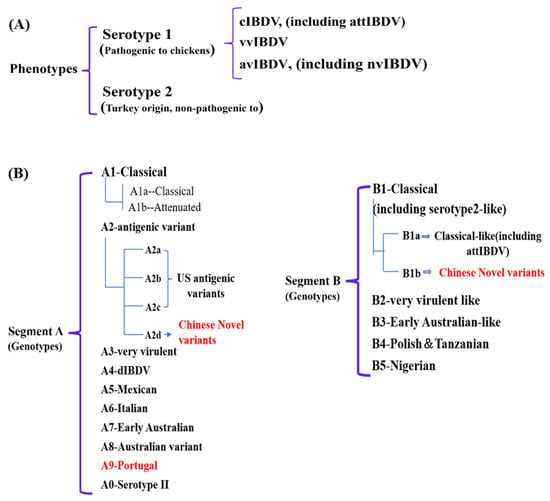

Infectious bursal disease (IBD), is an acute and highly contagious immunosuppressive disease of young chickens caused by infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) [1]. IBDV belongs to the family Birnaviridae and the genus Avibirnavirus, with a bi-segmented double-stranded RNA genome designated segments A and B. Segment A (~3.3 kb) encodes the nonstructural protein VP5 (~17 kDa), the capsid protein VP2 (~40 kDa), the scaffold protein VP3 (~32 kDa), and the viral protease VP4 (~28 kDa). VP2 is the major structural and host-protective immunogen, which are implicated in cell tropism, virulence, and antigenic variation [2]. Segment B (~2.8 kb) contains a single open reading frame encoding the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase VP1 (~90 kDa), which plays a crucial role in viral replication, genetic evolution, and virulence [2]. The virus primarily targets and destroys immature B lymphocytes in the bursa of Fabricius (BF), leading to severe immunosuppression, secondary infections, and reduced efficacy of vaccination against other pathogens [2]. Since its discovery in the 1960s in the United States, IBD has become one of the most important diseases in the poultry industry, with high morbidity, considerable mortality, and substantial economic losses worldwide. Two serotypes of IBDV have been identified: serotype 1, which is pathogenic, and serotype 2, which is nonpathogenic [3,4]. Over time, serotype 1 virus has evolved into multiple pathogenic strains, including classical (cIBDV) [5], very virulent (vvIBDV) [6], and antigenic variant (avIBDV) strains [7,8,9]. Similarly to other segmented RNA viruses, co-circulation of different types of IBDV strains in the field, combined with long-term immune pressure, facilitates viral evolution and the emergence of antigenic variants capable of escaping host immunity [10].

Owing to the rapid genetic variation occurring within the hypervariable region of the VP2 gene (vVP2) in field isolates, Michel and Jackwood [11] proposed a classification framework that divides IBDV into seven primary genogroups: classical, antigenic variant, vvIBDV, dIBDV, variant/classical recombinant, Italian (ITA) and Australian strains. This genotyping strategy generally corresponds to the earlier phenotype-based categorization. Nevertheless, accumulating evidence indicates that the pathogenic characteristics and evolutionary dynamics of IBDV are determined not only by mutations in vVP2, but also by genetic changes in the VP1 gene on segment B of the viral genome. A more comprehensive dual-segment genotyping system was subsequently introduced by Islam et al. [12], which categorized IBDV into nine genogroups of segment A (A1, classical; A2, US antigenic variant; A3, very virulent; A4, dIBDV; A5, atypical Mexican; A6, atypical Italian; A7, early Australian; A8, Australian variant and A0, serotype 2) and five genogroups of segment B (B1, classical-like; B2, very virulent-like; B3, early Australian-like; B4, Polish & Tanzanian and B5, Nigerian). Later, Y-L. Wang et al. [13] proposed a revised scheme that largely aligns with the classification of Islam et al. Our group found that the VP1 gene of the nvIBDV was different from the early classical-like (B1), so it was proposed to divide it into B1a (classical like) and B1b (Chinese novel variants), that is, the nvIBDV was a novel genotype (A2dB1b) (Figure 1) [10].

Figure 1.

The latest phenotypes (A) and genotypes (B) classification of IBDV. The red font indicates the newly emerged strains in recent years.

When selecting IBDV vaccines, poultry veterinarians must address key factors including maternal immunity, litter management, and desired protection endpoints [14,15,16]. Maternally derived antibodies (MDA) are crucial for the early post-hatch period protection but can interfere with vaccine efficacy [16,17]. Veterinarians must evaluate MDA levels, which are influenced by the vaccination protocols of breeder hens. In regions with well-established breeder vaccination programs, MDA provides early protection, but excessive MDA can impede active immunity in chicks, necessitating the use of vaccines compatible with MDA interference, such as immune complex (Icx) or recombinant vector vaccines [18,19]. Litter management also impacts vaccine choice, particularly in systems with reused litter where IBDV can persist between flocks, posing an early exposure risk. In these cases, vaccines offering early protection, like Icx or recombinant vectored vaccines, are essential. In contrast, systems with single-flock litter replacement and low environmental challenge may rely on breeder vaccination and biosecurity measures, reducing the need for active vaccination in broilers. Finally, vaccine selection must align with specific protection goals, including the timing, duration, and type of immunity required [20]. Live attenuated vaccines provide rapid immunity but may be less effective in high-MDA conditions, while inactivated vaccines, though slower to induce immunity, offer longer-lasting protection [14,15,16]. Vaccine choice should also account for circulating field strains and emerging variants [13].

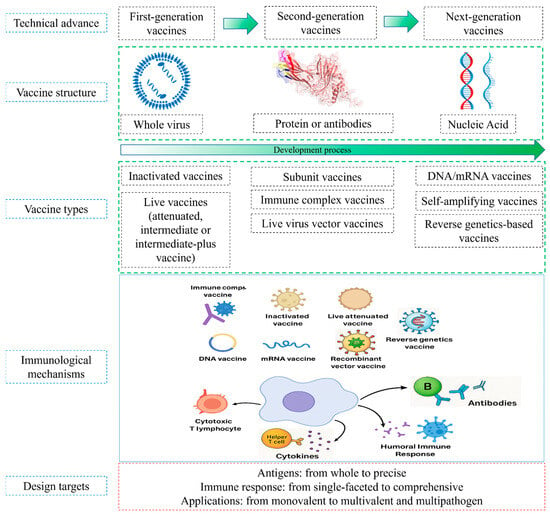

Vaccination remains the cornerstone of IBD control, with a variety of vaccines in use, including attenuated, inactivated, Icx, and recombinant viral vector vaccines, currently in use (Table 1). However, although these approaches have provided substantial protection, their efficacy is challenged by MDA interference, antigenic drift, and the potential for immunosuppression or reversion to virulence [14,15,16]. The continuous evolution of IBDV has stimulated the development of next-generation vaccines, including recombinant VP2-based subunit formulations, viral vector platforms, and nucleic acid vaccines, designed to improve safety, broaden cross-protection, and enhance immunogenicity. This review aims to summarize these research advances, focusing on the development of next-generation vaccines that promise higher safety, efficacy, and the ability to keep pace with the antigenic drift of IBDV (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Chronology of IBDV vaccine development.

Figure 2.

IBDV vaccine platforms, current advances and immunological mechanisms.

2. Conventional Live IBDV Vaccines

Live vaccines are prepared from attenuated or avirulent pathogens obtained through induced mutagenesis or natural selection. These vaccines can mimic natural infection by replicating within the host and inducing strong immune responses, including both cellular and humoral immunity. At present, live vaccines can be classified into three types, including mild, intermediate or intermediate-plus, and virulent [17,18]. Mild vaccines often show poor efficacy in chicks with MDA, since MDA interferes with viral replication. Therefore, waiting for an appropriate period of time until MDA levels weaken is crucial to achieve reliable immunity [19,20]. Intermediate and intermediate-plus vaccines (also known as “hot” vaccine) provide superior protection against field strain infections and can overcome relatively high levels of MDA; however, they may also induce BF lesions and subsequent immunosuppression [21,22]. Additionally, recent studies indicate that such vaccines do not fully protect against infection with vvIBDV or novel variant IBDV strains (nvIBDV) [23,24]. Virulent vaccines are rarely used in the industry due to their potential to cause severe BF damage in vaccinated flocks. Although live vaccines do not require adjuvants and can effectively stimulate immune responses, making them suitable for large-scale immunization in poultry, their safety and efficacy remain concerns. For example, genetic reassortment or homologous recombination between vaccine and field strains has been reported [10,25,26], and prolonged circulation of live vaccines in flocks can, in rare cases, result in selection toward increased virulence or altered antigenicity; these phenomena underline the need for careful vaccine strain selection and surveillance. Generally, live IBDV vaccines used in the poultry industry are derived from classical strains that are serially passaged in cells or chicken embryos to attenuate virulence while retaining strong immunogenicity [2]. Okura et al. developed an attenuated live vaccine (IBD-CA) from the cIBDV Lukert strain via chicken embryo fibroblast (CEF) culture, which provided better protection against vvIBDV challenge than the rHVT-VP2 vaccine [27]. Similarly, Leng et al. demonstrated that the attenuated live strain W2512 induced high levels of IBDV antibodies and protected chickens against nvIBDV infection via a placeholder effect; however, it also caused severe BF atrophy in both SPF chickens and commercial yellow-feathered broilers [28].

3. Conventional Inactivated IBDV Vaccines

The inactivated IBD vaccines are typically formulated as water-in-oil emulsions and often combined with multiple antigens, such as inactivated whole virus, recombinant virus, or viral subunits, etc. These vaccines are widely used in the industry due to their high safety and non-infectious [14]. Compared to live IBDV vaccines, inactivated vaccines can induce high levels of antibodies but generally elicit limited cellular immune responses unless combined with highly efficient adjuvants and repeatedly immunized. Rautenschlein et al. found that IBD inactivated vaccines can also stimulate IBDV-specific T-cell responses [29]. Generally, to achieve effective protection, inactivated IBDV vaccines need to contain high concentrations of optimized antigens, which can stimulate strong antibody responses in chickens and protect offspring against IBDV strains [30]. Wang et al. evaluated the protective efficacy of oil-emulsified inactivated vaccines (OEVs) prepared from two nvIBDV isolates, QZ191002 strain (A-nv/B-nv) and YL160304 (A-nv/B-HLJ0504-like), against nvIBDV challenge. Their findings demonstrated that a single priming dose of the commercial vaccines (without any antigen of nvIBDV) provided incomplete protection (40–60%), which was only partially improved to 60–80% with a booster. Crucially, only the homologous OEVs conferred complete protection (100%) [31]. Cui et al. demonstrated that recombinant chicken interleukin-7 (IL-7), as a potent adjuvant, can enhance the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of inactivated IBDV vaccines [32]. Many breeding companies use high-quality inactivated vaccines to immunize breeder hens before laying to provide passive immunity to chicks via MDA. Several high-quality inactivated IBDV vaccines have been developed, and the “prime-boost” immunization strategy is considered the most effective approach for inactivated vaccine immunization in field applications.

4. Immune Complex Vaccines

Immune complex vaccines (Icx) against IBDV were first developed in the late 1990s. These vaccines are composed of an intermediate-plus IBDV strain mixed with IBDV-specific antibodies obtained from the hyperimmunized serum, forming a virus–antibody complex (IBD-Icx) [33]. Notably, IBD-Icx vaccines have demonstrated efficacy even in the presence of high levels of MDA [34], whether administered via in ovo vaccination at day 18 using commercial automated egg-injection systems or via subcutaneous injection in one-day-old chicks, providing protection against both vvIBDV and avIBDV [35]. During the challenge, the experimental efficacy of the Icx vaccines was identical to or better than that induced by vaccination with live IBDV vaccines. Ivan et al. reported that viruses were first detected in the bursa of SPF chickens vaccinated with IBD-Icx at day 14 post-vaccination and were subsequently observed in chickens with MDA against IBDV between days 17 and 21 post-vaccination [36]. Due to IBD-Icx will initially remain bound to the surface of follicular dendritic cells present in the bursa of Fabricius and spleen, until maternal-derived antibodies (MDA) decrease to a point where the moderately virulent live vaccine can begin to replicate in the bursa without causing bursal atrophy or immunosuppression.

A major breakthrough has been the shift from polyclonal antisera to the use of recombinant neutralizing antibodies. This shift addresses critical issues of batch-to-batch variability and scalability associated with traditional hyperimmune serum. By cloning and expressing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) with defined neutralizing epitopes, researchers can now create standardized, well-characterized Icx vaccines. This precision allows for the fine-tuning of the antigen-to-antibody ratio, optimizing the complex’s size and stability to ensure efficient targeting and retention on follicular dendritic cells in lymphoid tissues. More recently, recombinant neutralizing antibodies have been developed for use in IBD-Icx vaccines [37]. Another promising frontier is the integration of Icx technology with nanoparticle delivery systems. The ultimate goal is to create “smart” vaccines that not only safely bypass pre-existing immunity but also actively direct the immune system towards a more potent and durable response.

5. Live Virus Vector Vaccines

Recombinant live virus vector vaccines are created by inserting the gene encoding the target antigen into harmless or attenuated bacteria or viruses, generating recombinant strains that replicate within the host. As these strains replicate, the target gene is expressed on a large scale, stimulating a protective immune response against both the vector and the target pathogen. The first-generation recombinant live virus vector vaccine for IBDV was developed in the early 1990s using fowlpox virus (FPV) expressing the IBDV VP2 protein (rFPV-VP2) [38]. This vaccine successfully induced IBDV-specific antibodies and protected chickens against IBDV challenge. However, its protection was less effective compared to traditional IBDV inactivated oil-emulsion vaccines [39]. A significant advancement was made by Eldaghayes, who developed the fpIBD1:IL-18 recombinant strain, which simultaneously expresses the IBDV VP2 protein and chicken interleukin-18 (IL-18). This recombinant vaccine provided complete protection against the IBDV F52/70 challenge [40]. Another recombinant vector vaccine was developed using Herpesvirus of turkey (HVT) as the vector [41]. Two commercial rHVT-VP2 vaccines, which express the VP2 protein from IBDV strains Faragher 52/70 and Variant E, were developed and licensed for international use in 2007 and 2015, respectively [42]. High levels of MDA have been confirmed not to interfere with the immune effect of the HVT-VP2 vaccine [43], and vaccination via in ovo or one day-old subcutaneous injection has proven to be safe and effective [44]. In addition, Hulten et al. developed a HVT-ND-IBD vaccine based on HVT vector, which enabling simultaneous protection against ND, IBD, and Marek’s disease virus (MDV) [45]. In addition to HVT, other viruses have been used to develop recombinant vector vaccines for IBDV [46], including MDV [47], NDV [48], avian adenovirus [49], semliki forest virus [50], baculoviruses [51] and T4 bacteriophage [52,52].

6. Subunit Vaccines

The capsid protein VP2 of IBDV has been the focus of subunit vaccine development due to its role as the primary host-protective antigen [30]. Multiple prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems, including Escherichia coli [53], yeast [54], baculovirus [55], Lactococcus lactis [56], and plant expression systems [57,58], have been developed for expressing and purifying the VP2 protein. Rong et al. developed a subunit vaccine using E. coli BL21/pET28a-VP2, which provided 90–100% protection in immunized chickens and has been widely applied for the IBD control [53,59]. Ji et al. expressed the IBDV VP2 protein in E. coli to develop an effective virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine and found that combining IBD VLPs with adjuvants significantly enhanced the vaccine’s immunogenicity [60]. Wang et al. successfully developed self-assembling sub-virus-like particle (sVLP) using Pichia pastoris and demonstrated that these vaccines induced high levels of IBDV-neutralizing antibodies, providing full protection against vvIBDV challenge [61].

Several other studies have focused on improving vaccine efficacy through different approaches. Pitcovski et al. achieved complete protection against IBDV using a yeast-expressed VP2 protein [62]. Martinez-Torrecuadrada et al. compared the immunogenicity and protective efficacy of various VP2 capsid structures and found that VP2 capsids elicited the strongest neutralizing response, followed by polyprotein-derived mixture and VPX nanotubes [51]. Liu et al. expressed a fusion protein of VP2 and chicken interleukin-2 (IL2) using an insect expression system, which significantly enhanced the immunogenicity of the VP2 protein [63]. Wang et al. used phage display technology to develop a multi-epitope protein vaccine (r5EPIS) with monoclonal antibody-binding peptides, which provided 100% protection in chickens challenged with vvIBDV GX8/99 [64]. More recently, Wang et al. developed a VP2 subunit vaccine using Lactococcus lactis to express VP2 from an nvIBDV, inducing unique neutralizing antibodies and providing 100% protection in immunized chickens [56]. Wu et al. developed an edible plant-derived IBDV-VP2 subunit vaccine, which stimulated chickens to produce specific antibodies following oral immunization with crude leaf extract [57]. Subsequently, Wu et al. developed an edible vaccine based on rice plants expressed VP2 protein specifically in seeds [65], which induced IBDV-specific neutralizing antibodies, with antibody titers increasing in a dose-dependent manner [66].

7. Reverse Genetics-Based Recombinant IBDV Live Vaccines

Advances in reverse genetics systems have greatly facilitated the generation of attenuated IBDV through targeted genomic modifications, providing potential candidates for vaccine development. Traditional attenuated vaccine strains are usually obtained by serial passage in cell culture or SPF embryos, or through natural isolation. However, these methods are often time-consuming, unpredictable, and particularly unsuitable for nvIBDV. Reverse genetics provides a more precise and efficient alternative. Based on these findings, several research groups have generated recombinant or chimeric IBDVs with attenuated phenotypes and strong immunogenicity. For example, Mosley et al. demonstrated that an IBDV rescued efficiently with 3′ authentic RNA sequence induces humoral immunity without BF atrophy but elicited stronger antibody responses as early as 7 days post-infection [67]. Similarly, mutation of the VP5 start codon yielded VP5-deficient mutants that retained replication competence, caused no clinical signs or lesions associated with the parental virus [68], yet induced comparable levels of IBDV-neutralizing antibodies [69]. Consistently, Qin et al. showed that VP5-deficient vvIBDV strains provided strong protection against wild-type vvIBDV challenge in chickens [70]. Boot et al. generated attenuated chimeric viruses by substituting the VP3 C-terminal region of serotype II with the corresponding region from serotype I [71]. Mundt et al. constructed a chimeric IBDV by substituting VP2 and VP4 of a classical vaccine strain with those from a variant strain, producing a virus with replication capacity equivalent to the classical vaccine strain but capable of inducing neutralizing antibodies against both classical and antigenic variant strains [72]. Likewise, Boot et al. demonstrated that substituting the VP3 C-terminal region of a serotype I vvIBDV with that of serotype II significantly reduced morbidity and mortality in vaccinated chickens [73]. Using an attenuated Gt strain as a backbone, Gao et al. generated a chimeric rGtHLJVP2, by replacing its VP2 with that of vvIBDV HLJ0504, which induced antibody titers comparable to the live attenuated vaccine B87, caused no clinical or pathological lesions in SPF chickens [74]. Gao et al. also found that the N-terminal domain of VP1 from vvIBDVs had a negative effect on viral replication in vitro while exhibiting a positive effect on viral replication in vivo [75]. However, Nouen et al. found that the association of the central polymerase domain (Dc) and non-coding regions (NCRs) at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the 88180 strain increased the titer of virus at 4 dpi, but it did not result in an increased pathogenicity in chickens [76]. Wang et al. demonstrated that the full region of the N-terminal of polymerase plays an important role in viral replication and pathogenicity, but the substitutions of its partial region or a single residual do not completely lead to the virus attenuation to Three-Yellow chickens, although that significantly reduces its pathogenicity [77]. More recently, Yang et al. reported that insertion of a FLAG tag at the VP1 C-terminus markedly reduced polymerase activity and virulence, highlighting a novel strategy for rapidly development of antigen-matched live vaccines against currently circulating nvIBDV strains [78].

8. Nucleic Acid Vaccines

8.1. DNA Vaccines

Jiang et al. developed DNA vaccines based on IBDV VP2 and VP3, with protection rates of 90% and 10% in chickens, respectively [79]. Fodor et al. directly muscularly immunized SPF chickens with a DNA vaccine constructed based on the polyprotein VP2/4/3 [80]. Although the VP2/4/3 polyprotein induced immune responses, only 55% of chickens were antibody-positive, and the overall protection rate was just 36%. Li et al. developed an oral DNA vaccine based on the VP2/4/3 polyprotein gene delivered by attenuated Salmonella Typhimurium, which elicited specific humoral responses in SPF chickens [81]. However, even after booster immunization with an inactivated vaccine, the protection rate reached only 73.3%. Mahmood et al. developed an oral DNA vaccine (EC/pRc-VP2) containing the vvIBDV VP2 gene delivered by E. coli DH5α, which provided 95.4% protection in chickens against the vvIBDV challenge, significantly higher than the protection achieved by the commercial attenuated D78 vaccine [82]. A prime-boost regimen, using a DNA vaccine for priming (in ovo or at day one) and an inactivated or vectored vaccine for boosting, confers protection in chickens, whereas in ovo DNA vaccination alone proves not sufficient to induce protective immunity. Park et al. immunized chicken embryos with a DNA vaccine containing the polyprotein VP2/4/3 gene, either alone or in combination with plasmids encoding IL-2 and chIFN-γ, followed by a booster with inactivated vaccine at one day post-hatch [83]. They found that the prime-boost strategy using the DNA vaccine and inactivated vaccine completely protected chickens against vvIBDV challenge, whereas the addition of chIL-2 or chIFN-γ did not enhance the protection rate. Negash et al. evaluated the efficacy of a cationic polymer PLGA-MP for delivering an IBDV-VP2 DNA vaccine in chickens and demonstrated that PLGA-MP significantly enhanced the immunogenicity of the VP2 DNA vaccine [84]. Moreover, other studies have reported that IL-2 [85] and IL-6 [86] can markedly improve the efficacy of DNA vaccines. To date, DNA vaccines against IBDV remain at the experimental research stage and have not yet been licensed for commercial use.

8.2. RNA Vaccines

RNA vaccines have become highly attractive in recent years. Early studies demonstrated that naked mRNA used as an immunogen can rapidly induce both humoral and cellular immune responses. However, initial development was constrained by challenges such as high production costs, instability during long-term storage and in vivo delivery, and complex manufacturing processes. Recent advances have shown that stable mRNA vaccines against infectious diseases can be produced under GMP conditions with high immunogenicity, which has driven the rapid development of mRNA vaccine technology. Currently, several mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have been approved for clinical use, including Pfizer’s BNT162b2, Moderna’s mRNA-1273, and Janssen’s Ad26.COV2.S. Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines require a two-dose regimen and storage at −20 °C to −70 °C, whereas the Janssen vaccine is approved as a single-dose formulation and can be stored for several months at 4 °C. To date, all SARS-CoV-2 vaccines target the original or optimized spike protein of the virus using various platforms, with over 50 RNA vaccine candidates in different stages of clinical trials. Current mRNA vaccine development efforts largely focus on preventing diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus (NCT05001373), influenza [87], rabies virus [88], Zika virus (NCT04064905), respiratory syncytial virus (NCT04528719), and cytomegalovirus (NCT04232280). Only a few mRNA vaccines have been developed for veterinary use, such as those against foot-and-mouth disease virus [89]. In 2022, Qu et al. reported a circular mRNA vaccine, circRNARBD-Delta, which demonstrates greater stability and resistance to exonuclease degradation compared to linear mRNA vaccines, and showed advantages in production, delivery, and therapeutic efficacy [90]. In 2024, Chen et al. further improved mRNA vaccine performance by engineering a novel structure with multiple poly (A) tails, significantly enhancing translation efficiency and stability [91]. Although challenges remain for the application of mRNA vaccines in veterinary medicine, their future potential is considerable. Promising directions include T cell-targeted mRNA vaccines against African swine fever virus (ASFV), VP2-based multivalent chimeric mRNA vaccines for IBDV and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), RBD-based mRNA vaccines against infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), and E2-based vaccines against swine fever virus.

To date, no licensed or experimentally validated mRNA vaccine specifically targeting IBDV has been reported. Nevertheless, we included a detailed overview of mRNA and saRNA vaccine technologies because these platforms have demonstrated rapid, safe, and effective antigen expression for multiple avian and mammalian viral pathogens, and they represent a promising next-generation strategy for IBDV control.

8.3. Self-Amplifying Vaccines

Self-amplifying vaccines, originating from the genomes of alphavirus, include Semliki Forest virus (SFV), Sindbis virus (SINV), and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (VEEV) [92,93]. Self-amplifying vaccine contains two open reading frames (ORFs). The first ORF encodes four non-structural proteins (nsP1-4), which were responsible for the replication and amplification of the viral genome. The second ORF encodes an exogenous target antigen, which is expressed through sub-genomic RNA generated by replicase-driven transcription initiated at the viral 26S sub-genomic promoter, enabling continuous and large-scale expression of the target antigen. Unlike conventional non-amplifying nucleic acid vaccines that only encode the target antigen gene, self-amplifying vaccines can achieve prolonged and enhanced antigen expression even at very low RNA doses [94], thereby inducing stronger humoral and cellular immune responses [95]. Recently, the first fully licensed self-amplifying nucleic acid vaccine in the world, ARCT-154, developed by Arcturus Therapeutics (USA) and CSL (Japan), and was approved by Japanese health authorities [96]. Additionally, in 2022, India approved a self-amplifying vaccine named Gemcovac-19, produced by Gennova Biopharmaceuticals (Pune, India), for emergency use only. Jerome et al. developed a bird-adapted VEEV-based self-amplifying mRNA versatile vaccine platform successfully expressed AIV HA and IBDV pVP2 proteins, generating high levels neutralizing antibodies in poultry and highlighting the significant potential against emerging pathogens [97]. Currently, self-amplifying nucleic acid vaccines have been applied to various emerging or re-emerging infectious diseases in both humans and animals, such as SARS-CoV-2 [98], HIV-1 [99], influenza virus [94], rabies virus (NCT04062669), Zika virus [100], respiratory syncytial virus [101], botulism [102], foot-and-mouth disease virus [103], classical swine fever virus [104], and goatpox virus [105].

9. Field Performance and Application of IBDV Vaccines

While technological innovation in vaccine platforms provides the tools for control, under field conditions, the performance of infectious BF disease virus (IBDV) vaccines is shaped not only by antigenic compatibility and formulation but also by poultry management, biosecurity standards, and interference from MDA. Commercial broilers are particularly susceptible to early infection when MDA levels decline, co-infections with other pathogens or an environment where high viruses circulate. Previous studies indicate that live attenuated vaccines induce immunity rapidly but are strongly affected by MDA, while inactivated and Icx vaccines provide slower yet more consistent protection under high-MDA conditions [14]. Recombinant HVT-VP2 vaccines confer long-lasting immunity with minimal MDA interference, making them suitable for large-scale hatchery use. Ultimately, the selection of vaccine type should be guided by Prevalent Genotypes and Antigenic Types, Antigenic Drift and Emerging Variants, and MDA interference, which remains the cornerstone strategy for preventing IBD-associated immunosuppression in commercial poultry.

10. Breeder Hen Vaccination and MDA Dynamics

Vaccination of breeder hens plays a pivotal role in providing passive immunity to progeny. The primary objective is to elicit high titers of neutralizing antibodies in hens that are efficiently transferred to chicks via the egg yolk, offering early protection during the critical post-hatch period [19]. These MDA protect chicks for 2–3 weeks, bridging the gap before their immune systems mature. The duration and level of MDA are influenced by vaccine formulation, adjuvant choice, and booster timing. Oil-emulsified inactivated vaccines are most commonly used in breeders due to their prolonged antibody persistence. The breeder vaccination protocols typically employ a prime-boost regimen, utilizing live vaccines followed by inactivated, oil-adjuvanted vaccines prior to the onset of lay to ensure persistent and high-level antibody production [14,30]. While robust MDA is indispensable for early protection, excessively high-MDA titers can interfere with early progeny vaccination [19,20]. Therefore, precise scheduling of breeder vaccination is required to synchronize MDA decay with the onset of active immunity in chicks, optimizing flock-level protection.

11. The Critical Age Window for BF Protection and Time to Antibody Induction by Vaccine Type

Protection of the bursa of Fabricius is essential between 14 and 35 days of age, when B-cell development is most active. Infection during this period can result in irreversible immunosuppression, poor vaccine responsiveness, and increased susceptibility to secondary infections. Effective vaccination aims to induce protective antibody levels before 14 days of age, especially in regions where very virulent (vvIBDV) or novel variant IBDV (nvIBDV) strains are prevalent. Under conditions of high-challenge pressure, early immunization through Icx or recombinant vector vaccines provides extended coverage throughout this critical developmental window (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparative characteristics across major IBDV vaccine types.

12. Early Challenge and Reused Litter Conditions

In broiler production systems that reuse litter, residual IBDV can persist between flocks, leading to early infection as soon as 5–7 days post-hatch. Such early exposure frequently occurs before active immunity develops. Icx and recombinant vectored vaccines are particularly suitable for these environments, as they are less affected by MDA and provide early protection through mechanisms such as delayed virus release and sustained antigen presentation [34,35,36,37,44]. Conversely, conventional live attenuated vaccines may fail due to rapid neutralization by MDA. Robust breeder vaccination remains an indispensable adjunct to protect chicks during this vulnerable period.

13. Vaccination Necessity Under Low-Challenge Environments

In poultry operations employing single-flock litter replacement and maintaining high biosecurity, the environmental load of IBDV is significantly reduced. In such low-challenge conditions, active broiler vaccination may be unnecessary if breeder hens have been effectively immunized. Decision-making should consider factors such as historical farm challenge rates, presence of vvIBDV or nvIBDV strains, flock density, and cost–benefit analysis. In low-risk systems, reliance on passive immunity from breeder vaccination combined with strict hygiene can be both effective and economically advantageous. Nonetheless, sentinel monitoring and periodic serological surveillance are recommended to ensure continued protection and early detection of viral re-emergence.

14. Conclusions and Future Directions

The continuous evolution of IBDV, particularly the emerge of very virulent and antigenic variant strains, poses a significant challenge to the conventional vaccination strategies. While traditional live-attenuated and inactivated vaccines have played a crucial role in controlling IBD, their limitations, such as MDA interference, potential reversion to virulence, and insufficient cross-protection, highlight the need for more advanced vaccine platforms to develop new types of vaccines that can keep pace with the evolution of viruses.

Effective IBDV vaccination strategies must be tailored to the epidemiological context and the management and biosecurity programs in which they are applied. In commercial broilers, protection is determined not only by the intrinsic efficacy of the vaccine strain but also by MDA interference, timing of administration, and challenge pressure. MDA plays a critical role in providing early immunity to chicks but can also interfere with the induction of active immunity, especially when MDA levels are too high. In systems with high MDA, immune-complex vaccines (rapid immune activation), recombinant vectored vaccines and subunit vaccines (offer safer and longer-lasting immunity) show promise by offering protection despite MDA interference. Nevertheless, the choice of vaccine should reflect local virus circulation patterns, litter management, and biosecurity standards.

Breeder hen vaccination remains central to flock protection, as MDA transfer shields chicks during their first 2–3 weeks of life—when they are most susceptible to infection. The balance between robust MDA levels and the timing of broiler vaccination is critical, as excessive MDA may delay active immune induction. Under high-challenge conditions or when litter is reused, immune-complex and recombinant vectored vaccines are preferred because they confer earlier and more consistent protection despite MDA interference. Conversely, in low-risk environments with single-flock litter replacement and stringent biosecurity, reliance on breeder immunization and environmental control may be sufficient, avoiding unnecessary vaccination costs. The critical window for protecting the bursa of Fabricius, generally between 14 and 35 days of age, must be considered when designing vaccination programs. Damage to the bursa during this stage results in irreversible immunosuppression and decreased responsiveness to other poultry vaccines. The integration of vaccine type, administration timing, and local risk assessment is therefore essential for sustainable disease control.

Moreover, gene editing technologies, such as reverse genetics systems and CRISPR/Cas9, offer exciting potential for developing precision vaccines against IBDV. By enabling precise modifications to viral antigens, gene editing technologies can help create vaccines that are tailored to emerging viral strains and variants. This technology allows for rapid adaptation of vaccines to new IBDV strains, potentially overcoming challenges such as antigenic drift and improving cross-protection. The application of gene editing technologies in vaccine development is still in its early stages, but it holds promise as a tool for generating highly specific vaccines that address the evolving challenges posed by IBDV.

At present, mRNA vaccines have not yet been developed or validated for IBDV; however, their rapid design cycle, strong immunogenicity, and flexible antigen-encoding capacity make them an attractive platform for future research. Advances achieved in mRNA vaccines for other avian and mammalian pathogens could be readily leveraged for IBDV, particularly for generating VP2 antigen constructs capable of overcoming antigenic drift and maternal antibody interference. Future work should evaluate delivery systems suitable for poultry, thermostability improvements for field conditions, and in vivo expression efficiency in the bursa-associated immune environment.

Looking ahead, future IBDV vaccine development should aim to combine strong early protection, broad antigenic coverage, and compatibility with hatchery-based delivery systems such as in ovo or spray vaccination. The continuous antigenic drift of IBDV necessitates ongoing surveillance and timely updates to vaccine strains. Recombinant vectored vaccines, reverse genetics, mRNA platforms, and multivalent recombinant constructs represent promising directions for next-generation vaccines. Ultimately, the success of IBD control depends not only on vaccine innovation but also on the rational application of vaccination within comprehensive management frameworks that consider MDA dynamics, environmental challenge, and production economics.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft preparation: W.W. Literature and illustrations: W.W., J.W., N.J., Q.L., R.L. and Q.F. Conceptualization and methodology: W.W., G.F., T.W., C.W., L.C. and Y.H. Writing—review and editing: X.H., P.W., H.C. and Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2025J08104), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31660717, 32160824 and 31560706), and the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (YCBZ2022034).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript was kindly reviewed by Richard Roberts, Aurora, CO80014, USA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Berg, T.P. Acute infectious bursal disease in poultry: A review. Avian Pathol. 2000, 29, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, H.; Islam, M.R.; Raue, R. Research on infectious bursal disease—The past, the present and the future. Vet. Microbiol. 2003, 97, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackwood, D.J.; Saif, Y.M.; Hughes, J.H. Characteristics and serologic studies of two serotypes of infectious bursal disease virus in turkeys. Avian Dis. 1982, 26, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, N.M.; Saif, Y.M.; Moorhead, P.D. Lack of pathogenicity of five serotype 2 infectious bursal disease viruses in chickens. Avian Dis. 1988, 32, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, A.S. An Apparently New Disease of Chickens: Avian Nephrosis. Avian Dis. 1962, 6, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettle, N.; Stuart, J.C.; Wyeth, P.J. Outbreak of virulent infectious bursal disease in East Anglia. Vet. Rec. 1989, 125, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackwood, D.H.; Saif, Y.M. Antigenic diversity of infectious bursal disease viruses. Avian Dis. 1987, 31, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wu, T.; Hussain, A.; Gao, Y.; Zeng, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Novel variant strains of infectious bursal disease virus isolated in China. Vet. Microbiol. 2019, 230, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, J.; Chen, R.; Chen, J.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, G.; et al. Analysis of the global origin, evolution and transmission dynamics of the emerging novel variant IBDV (A2dB1b): The accumulation of critical aa-residue mutations and commercial trade contributes to the emergence and transmission of novel variants. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e2832–e2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Deng, Q.; Chen, R.; Chen, J.; Huang, T.; Wei, T.; Mo, M.; et al. The emerging naturally reassortant strain of IBDV (genotype A2dB3) having segment A from Chinese novel variant strain and segment B from HLJ 0504-like very virulent strain showed enhanced pathogenicity to three-yellow chickens. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e566–e579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, L.O.; Jackwood, D.J. Classification of infectious bursal disease virus into genogroups. Arch. Virol. 2017, 162, 3661–3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Rahman, T.; Mumu, T.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Chowdhury, E.H.; Eterradossi, N.; Müller, H. A unified genotypic classification of in-fectious bursal disease virus based on both genome segments. Avian Pathol. 2021, 50, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Fan, L.-J.; Jiang, N.; Gao, L.; Li, K.; Gao, Y.-L.; Liu, C.-J.; Cui, H.Y.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, Y.-P.; et al. An improved schemefor infectious bursal disease virus genotype classification based on both genome-segments A and B. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, H.; Mundt, E.; Eterradossi, N.; Islam, M.R. Current status of vaccines against infectious bursal disease. Avian Pathol. 2012, 41, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackwood, D.J. Advances in vaccine research against economically important viral diseases of food animals: Infectious bursal disease virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 206, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramon, G.; Legnardi, M.; Cecchinato, M.; Cazaban, C.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Fiorentini, L.; Gambi, L.; Mato, T.; Berto, G.; Koutoulis, K.; et al. Efficacy of live attenuated, vector and immune complex infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) vaccines in preventing field strain bursa colonization: A European multicentric study. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 978901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautenschlein, S.; Kraemer, C.; Vanmarcke, J.; Montiel, E. Protective efficacy of intermediate and intermediate plus infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) vaccines against very virulent IBDV in commercial broilers. Avian Dis. 2005, 49, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harm, J.G.; Ellen, O.; Gert Jan, B.; Dieter, V. Efficacy, Safety, and Interactions of a Live Infectious Bursal Disease Virus Vaccine for Chickens Based on Strain IBD V877. Avian Dis. 2014, 59, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, T.P.; Meulemans, G. Acute infectious bursal disease in poultry: Protection afforded by maternally derived antibodies and interference with live vaccination. Avian Pathol. 1991, 20, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, W.; Giambrone, J.J.; Williams, J.C.; Lauerman, L.H.; Panangala, V.S.; Garces, C. Effect of maternal antibody on timing of initial vaccination of young white leghorn chickens against infectious bursal disease virus. Avian Dis. 1986, 30, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazariegos, L.A.; Lukert, P.D.; Brown, J. Pathogenicity and immunosuppressive properties of infectious bursal disease “intermediate” strains. Avian Dis. 1990, 34, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, K.; Tanimura, N.; Kakita, S.; Ota, K.; Mase, M.; Imai, K.; Hihara, H. Efficacy of three live vaccines against highly virulent infectious bursal disease virus in chickens with or without maternal antibodies. Avian Dis. 1995, 39, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wu, T.; Wang, Y.; Hussain, A.; Jiang, N.; Gao, L.; Li, K.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C.; Cui, H.; et al. Novel variants of infectious bursal disease virus can severely damage the bursa of fabricius of immunized chickens. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 240, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Wang, C.Y.; Luo, Z.B.; Shao, G.Q. Commercial vaccines used in China do not protect against a novel infectious bursal disease virus variant isolated in Fujian. Vet. Rec. 2022, 191, e1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Xiong, Z.; Yang, L.; Guan, D.; Yang, X.; Wei, P. Molecular epidemiology studies on partial sequences of both genome segments reveal that reassortant infectious bursal disease viruses were dominantly prevalent in southern China during 2000–2012. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 3279–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Fan, L.; Jiang, N.; Gao, L.; Li, K.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C.; Cui, H.; et al. Naturally occurring homologous recombination between novel variant infectious bursal disease virus and intermediate vaccine strain. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 245, 108700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okura, T.; Otomo, H.; Suzuki, S.; Ono, Y.; Taneno, A.; Oishi, E. Efficacy of a novel in ovo-attenuated live vaccine and recombinant vaccine against a very virulent infectious bursal disease virus in chickens. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 1686–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, M.; Bian, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Z.; Lian, J.; Chen, M.; Chen, F.; Wang, Z.; Lin, W. The attenuated live vaccine strain W2512 provides protection against novel variant infectious bursal disease virus. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautenschlein, S.; Yeh, H.Y.; Sharma, J.M. The role of T cells in protection by an inactivated infectious bursal disease virus vaccine. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2002, 89, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, H.; Schnitzler, D.; Bernstein, F.; Becht, H.; Cornelissen, D.; Lutticken, D.H. Infectious bursal disease of poultry: Antigenic structure of the virus and control. Vet. Microbiol. 1992, 33, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, J.; Huang, J.; Huang, T.; Wei, T.; Mo, M.; He, X.; et al. The complete protections induced by the oil emulsion vaccines of the novel variant infectious bursal disease viruses against the homologous challenges indicating the important roles of both VP2 and VP1 in the antigenicity and pathogenicity of the virus. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1466099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, Y.; Huo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhong, F. Recombinant chicken interleukin-7 as a potent adjuvant increases the immunogenicity and protection of inactivated infectious bursal disease vaccine. Vet. Res. 2018, 49, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitfill, C.E.; Haddad, E.E.; Ricks, C.A.; Skeeles, J.K.; Newberry, L.A.; Beasley, J.N.; Andrews, P.D.; Thoma, J.A.; Wakenell, P.S. Determination of optimum formulation of a novel infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) vaccine constructed by mixing bursal disease antibody with IBDV. Avian Dis. 1995, 39, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, E.E.; Whitfill, C.E.; Avakian, A.P.; Ricks, C.A.; Andrews, P.D.; Thoma, J.A.; Wakenell, P.S. Efficacy of a novel infectious bursal disease virus immune complex vaccine in broiler chickens. Avian Dis. 1997, 41, 882–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeurissen, S.H.; Janse, E.M.; Lehrbach, P.R.; Haddad, E.E.; Avakian, A.; Whitfill, C.E. The working mechanism of an immune complex vaccine that protects chickens against infectious bursal disease. Immunology 1998, 95, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivan, J.; Velhner, M.; Ursu, K.; German, P.; Mato, T.; Dren, C.N.; Meszaros, J. Delayed vaccine virus replication in chickens vaccinated subcutaneously with an immune complex infectious bursal disease vaccine: Quantification of vaccine virus by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Can. J. Vet. Res. = Rev. Can. Rech. Vet. 2005, 69, 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ignjatovic, J.; Gould, G.; Trinidad, L.; Sapats, S. Chicken recombinant antibodies against infectious bursal disease virus are able to form antibody-virus immune complex. Avian Pathol. 2006, 35, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, C.D.; Peters, R.W.; Cook, J.K.; Reece, R.L.; Howes, K.; Binns, M.M.; Boursnell, M.E. A recombinant fowlpox virus that expresses the VP2 antigen of infectious bursal disease virus induces protection against mortality caused by the virus. Arch. Virol. 1991, 120, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, H.G.; Boyle, D.B. Infectious bursal disease virus structural protein VP2 expressed by a fowlpox virus recombinant confers protection against disease in chickens. Arch. Virol. 1993, 131, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldaghayes, I.; Rothwell, L.; Skinner, M.; Dayhum, A.; Kaiser, P. Efficacy of Fowlpox Virus Vector Vaccine Expressing VP2 and Chicken Interleukin-18 in the Protection against Infectious Bursal Disease Virus. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darteil, R.; Bublot, M.; Laplace, E.; Bouquet, J.F.; Audonnet, J.C.; Riviere, M. Herpesvirus of turkey recombinant viruses expressing infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) VP2 immunogen induce protection against an IBDV virulent challenge in chickens. Virology 1995, 211, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrao, F.; Rauw, F.; van den Berg, T.; Lambrecht, B. Characterization of two recombinant HVT-IBD vaccines by VP2 insert detection and cell-mediated immunity after vaccination of specific pathogen-free chickens. Avian Pathol. 2017, 46, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bublot, M.; Pritchard, N.; Le Gros, F.X.; Goutebroze, S. Use of a vectored vaccine against infectious bursal disease of chickens in the face of high-titred maternally derived antibody. J. Comp. Pathol. 2007, 137, S81–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, K.; Saito, S.; Saeki, S.; Sato, T.; Tanimura, N.; Isobe, T.; Mase, M.; Imada, T.; Yuasa, N.; Yamaguchi, S. Complete, long-lasting protection against lethal infectious bursal disease virus challenge by a single vaccination with an avian herpesvirus vector expressing VP2 antigens. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5637–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Hulten, M.C.W.; Cruz-Coy, J.; Gergen, L.; Pouwels, H.; ten Dam, G.B.; Verstegen, I.; de Groof, A.; Morsey, M.; Tarpey, I. Efficacy of a turkey herpesvirus double construct vaccine (HVT-ND-IBD) against challenge with different strains of Newcastle disease, infectious bursal disease and Marek’s disease viruses. Avian Pathol. 2021, 50, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruud, H.; Rik, K.; Maricarmen, G.; Natalie, A.; John, R.D.; Taylor, B.; Algis, M. Review of Poultry Recombinant Vector Vaccines. Avian Dis. 2021, 65, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukamoto, K.; Kojima, C.; Komori, Y.; Tanimura, N.; Mase, M.; Yamaguchi, S. Protection of chickens against very virulent infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) and Marek’s disease virus (MDV) with a recombinant MDV expressing IBDV VP2. Virology 1999, 257, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Elankumaran, S.; Yunus, A.S.; Samal, S.K. A recombinant Newcastle disease virus (NDV) expressing VP2 protein of infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) protects against NDV and IBDV. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 10054–10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, A.; Chevalier, C.; Delmas, B.; Eterradossi, N.; Toquin, D.; Rivallan, G.; Langlois, P. Avian adenovirus CELO recombinants expressing VP2 of infectious bursal disease virus induce protection against bursal disease in chickens. Vaccine 2004, 22, 2351–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phenix, K.V.; Wark, K.; Luke, C.J.; Skinner, M.A.; Smyth, J.A.; Mawhinney, K.A.; Todd, D. Recombinant Semliki Forest virus vector exhibits potential for avian virus vaccine development. Vaccine 2001, 19, 3116–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Torrecuadrada, J.L.; Saubi, N.; Pages-Mante, A.; Caston, J.R.; Espuna, E.; Casal, J.I. Structure-dependent efficacy of infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) recombinant vaccines. Vaccine 2003, 21, 3342–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.C.; Shi, Q.C.; Ma, J.Y.; Xie, Q.M.; Bi, Y.Z. Vaccination against very virulent infectious bursal disease virus using recombinant T4 bacteriophage displaying viral protein VP2. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2005, 37, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Jiang, T.; Cheng, T.; Shen, M.; Du, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Xu, B.; Fan, G. Large-scale manufacture and use of recombinant VP2 vaccine against infectious bursal disease in chickens. Vaccine 2007, 25, 7900–7908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, K.J.; Chapman, A.J.; Macreadie, I.G.; Vaughan, P.R.; McKern, N.M.; Skicko, J.I.; Ward, C.W.; Azad, A.A. A recombinant subunit vaccine that protects progeny chickens from infectious bursal disease. Avian Pathol. 1991, 20, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakharia, V.N.; Snyder, D.B.; He, J.; Edwards, G.H.; Savage, P.K.; Mengel-Whereat, S.A. Infectious bursal disease virus structural proteins expressed in a baculovirus recombinant confer protection in chickens. J. Gen. Virol. 1993, 74, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mi, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Qi, X.; Li, K.; Pan, Q.; Gao, Y.; Gao, L.; Liu, C.; et al. Recombinant Lactococcus Expressing a Novel Variant of Infectious Bursal Disease Virus VP2 Protein Can Induce Unique Specific Neutralizing Antibodies in Chickens and Provide Complete Protection. Viruses 2020, 12, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Singh, N.K.; Locy, R.D.; Scissum-Gunn, K.; Giambrone, J.J. Immunization of chickens with VP2 protein of infectious bursal disease virus expressed in Arabidopsis thaliana. Avian Dis. 2004, 48, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, E.; Lucero, M.S.; Chimeno Zoth, S.; Carballeda, J.M.; Gravisaco, M.J.; Berinstein, A. Transient expression of VP2 in Nicotiana benthamiana and its use as a plant-based vaccine against Infectious Bursal Disease Virus. Vaccine 2013, 31, 2623–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Cheng, T.; Liu, X.; Jiang, T.; Gu, H.; Zou, G. Development of recombinant VP2 vaccine for the prevention of infectious bursal disease of chickens. Vaccine 2005, 23, 4844–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, P.; Li, T.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Li, L.; Shi, X.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, T.; et al. Virus-like Particle Vaccines of Infectious Bursal Disease Virus Expressed in Escherichia coli Are Highly Immunogenic and Protect against Virulent Strain. Viruses 2023, 15, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Pan, Q.; Lu, Z.; Li, K.; Gao, H.; Qi, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X. An optimized, highly efficient, self-assembled, subvirus-like particle of infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV). Vaccine 2016, 34, 3508–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitcovski, J.; Gutter, B.; Gallili, G.; Goldway, M.; Perelman, B.; Gross, G.; Krispel, S.; Barbakov, M.; Michael, A. Development and large-scale use of recombinant VP2 vaccine for the prevention of infectious bursal disease of chickens. Vaccine 2003, 21, 4736–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wu, X.; Yu, L. Preparation of ChIL-2 and IBDV VP2 fusion protein by baculovirus expression system. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2005, 2, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.S.; Fan, H.J.; Li, Y.; Shi, Z.L.; Pan, Y.; Lu, C.P. Development of a multi-mimotope peptide as a vaccine immunogen for infectious bursal disease virus. Vaccine 2007, 25, 4447–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yu, L.; Li, L.; Hu, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, X. Oral immunization with transgenic rice seeds expressing VP2 protein of infectious bursal disease virus induces protective immune responses in chickens. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007, 5, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rage, E.; Marusic, C.; Lico, C.; Baschieri, S.; Donini, M. Current state-of-the-art in the use of plants for the production of recombinant vaccines against infectious bursal disease virus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 2287–2296. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, Y.Y.; Wu, C.C.; Lin, T.L. Infectious bursal disease virus rescued efficiently with 3′ authentic RNA sequence induces humoral immunity without bursal atrophy. Vaccine 2013, 31, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Goodwin, M.A.; Vakharia, V.N. Generation of a mutant infectious bursal disease virus that does not cause bursal lesions. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 2647–2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, E.; Kollner, B.; Kretzschmar, D. VP5 of infectious bursal disease virus is not essential for viral replication in cell culture. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 5647–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Qi, X.; Gao, Y.; Gao, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Bu, Z.; Wang, X. VP5-deficient mutant virus induced protection against challenge with very virulent infectious bursal disease virus of chickens. Vaccine 2010, 28, 3735–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, H.J.; ter Huurne, A.A.; Vastenhouw, S.A.; Kant, A.; Peeters, B.P.; Gielkens, A.L. Rescue of infectious bursal disease virus from mosaic full-length clones composed of serotype I and II cDNA. Arch. Virol. 2001, 146, 1991–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mundt, E.; de Haas, N.; van Loon, A.A. Development of a vaccine for immunization against classical as well as variant strains of infectious bursal disease virus using reverse genetics. Vaccine 2003, 21, 4616–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, H.J.; ter Huurne, A.A.; Hoekman, A.J.; Pol, J.M.; Gielkens, A.L.; Peeters, B.P. Exchange of the C-terminal part of VP3 from very virulent infectious bursal disease virus results in an attenuated virus with a unique antigenic structure. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 10346–10355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Qi, X.; Li, K.; Gao, H.; Gao, Y.; Qin, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Development of a tailored vaccine against challenge with very virulent infectious bursal disease virus of chickens using reverse genetics. Vaccine 2011, 29, 5550–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Li, K.; Qi, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, X. N-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus contributes to viral replication and virulence. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouën, C.L.; Toquin, D.; Müller, H.; Raue, R.; Kean, K.M.; Langlois, P.; Cherbonnel, M.; Eterradossi, N. Different domains of the RNA polymerase of infectious bursal disease virus contribute to virulence. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e28064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, M.; Li, M.; Huang, T.; Wei, T.; et al. The Full Region of N-Terminal in Polymerase of IBDV Plays an Important Role in Viral Replication and Pathogenicity: Either Partial Region or Single Amino Acid V4I Substitution Does Not Completely Lead to the Virus Attenuation to Three-Yellow Chickens. Viruses 2021, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ye, C. Rapid Generation of Attenuated Infectious Bursal Disease Virus from Dual-Promoter Plasmids by Reduction of Viral Ribonucleoprotein Activity. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01569-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Chen, P.; Cai, B.; Huang, B. Immunological tests of the main structural protein genes and their expression products of infectious bursal disease virus. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 1998, 21, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fodor, N.; Dube, S.K.; Fodor, I.; Horvath, E.; Nagy, E.; Vakharia, V.N.; Rencendorsh, A. Induction of protective immunity in chickens immunised with plasmid DNA encoding infectious bursal disease virus antigens. Acta Vet. Hung. 1999, 47, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Fang, W.; Li, J.; Fang, L.; Huang, Y.; Yu, L. Oral DNA vaccination with the polyprotein gene of infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) delivered by attenuated Salmonella elicits protective immune responses in chickens. Vaccine 2006, 24, 5919–5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.S.; Hussain, I.; Siddique, M.; Akhtar, M.; Ali, S. DNA vaccination with VP2 gene of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus (vvIBDV) delivered by transgenic E. coli DH5alpha given orally confers protective immune responses in chickens. Vaccine 2007, 25, 7629–7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Sung, H.W.; Yoon, B.I.; Kwon, H.M. Protection of chicken against very virulent IBDV provided by in ovo priming with DNA vaccine and boosting with killed vaccine and the adjuvant effects of plasmid-encoded chicken interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma. J. Vet. Sci. 2009, 10, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negash, T.; Liman, M.; Rautenschlein, S. Mucosal application of cationic poly(d,l-lactide-co-glycolide) microparticles as carriers of DNA vaccine and adjuvants to protect chickens against infectious bursal disease. Vaccine 2013, 31, 3656–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liang, X.; Huang, Y.; Meng, S.; Xie, R.; Deng, R.; Yu, L. Enhancement of the immunogenicity of DNA vaccine against infectious bursal disease virus by co-delivery with plasmid encoding chicken interleukin 2. Virology 2004, 329, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.H.; Yan, Y.X.; Jiang, J.; Lu, P. DNA immunization against very virulent infectious bursal disease virus with VP2-4-3 gene and chicken IL-6 gene. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 2005, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freyn, A.W.; Ramos da Silva, J.; Rosado, V.C.; Bliss, C.M.; Pine, M.; Mui, B.L.; Tam, Y.K.; Madden, T.D.; de Souza Ferreira, L.C.; Weissman, D.; et al. A Multi-Targeting, Nucleoside-Modified mRNA Influenza Virus Vaccine Provides Broad Protection in Mice. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 1569–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, C.; Leroux-Roels, I.; Huang, K.B.; Bica, M.A.; Loeliger, E.; Schoenborn-Kellenberger, O.; Walz, L.; Leroux-Roels, G.; von Sonnenburg, F.; Oostvogels, L. Proof-of-concept of a low-dose unmodified mRNA-based rabies vaccine formulated with lipid nanoparticles in human volunteers: A phase 1 trial. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, M.R.; Sobrino, F.; Borrego, B.; Sáiz, M. RNA immunization can protect mice against foot-and-mouth disease virus. Antivir. Res. 2010, 85, 556–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Yi, Z.; Shen, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, F.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Tang, H.; Zhang, X.; Tian, F.; et al. Circular RNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. Cell 2022, 185, 1728–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liu, D.; Guo, J.; Aditham, A.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, J.; Luo, S.; Ren, J.; Hsu, A.; Huang, J.; et al. Branched chemically modified poly(A) tails enhance the translation capacity of mRNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljungberg, K.; Liljeström, P. Self-replicating alphavirus RNA vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Briones, M.C.; Silva-Pilipich, N.; Herrador-Cañete, G.; Vanrell, L.; Smerdou, C. A new generation of vaccines based on alphavirus self-amplifying RNA. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2020, 44, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.B.; Lambert, L.; Kinnear, E.; Busse, D.; Erbar, S.; Reuter, K.C.; Wicke, L.; Perkovic, M.; Beissert, T.; Haas, H.; et al. Self-Amplifying RNA Vaccines Give Equivalent Protection against Influenza to mRNA Vaccines but at Much Lower Doses. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitner, W.W.; Hwang, L.N.; deVeer, M.J.; Zhou, A.; Silverman, R.H.; Williams, B.R.; Dubensky, T.W.; Ying, H.; Restifo, N.P. Alphavirus-based DNA vaccine breaks immunological tolerance by activating innate antiviral pathways. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therapeutics, A.; CSL. First self-amplifying mRNA vaccine approved. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Comes, J.D.G.; Doets, K.; Zegers, T.; Kessler, M.; Slits, I.; Ballesteros, N.A.; van de Weem, N.M.P.; Pouwels, H.; van Oers, M.M.; van Hulten, M.C.W.; et al. Evaluation of bird-adapted self-amplifying mRNA vaccine formulations in chickens. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2895–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, J.G.; de Alwis, R.; Chen, S.; Kalimuddin, S.; Leong, Y.S.; Mah, T.K.L.; Yuen, N.; Tan, H.C.; Zhang, S.L.; Sim, J.X.Y.; et al. A phase I/II randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of a self-amplifying Covid-19 mRNA vaccine. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wecker, M.; Gilbert, P.; Russell, N.; Hural, J.; Allen, M.; Pensiero, M.; Chulay, J.; Chiu, Y.L.; Abdool Karim, S.S.; Burke, D.S. Phase I safety and immunogenicity evaluations of an alphavirus replicon HIV-1 subtype C gag vaccine in healthy HIV-1-uninfected adults. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. CVI 2012, 19, 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, J.H.; Khandhar, A.P.; Guderian, J.; Granger, B.; Archer, J.; Archer, M.; Gage, E.; Fuerte-Stone, J.; Larson, E.; Lin, S.; et al. A Nanostructured Lipid Carrier for Delivery of a Replicating Viral RNA Provides Single, Low-Dose Protection against Zika. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2507–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleeton, M.N.; Chen, M.; Berglund, P.; Rhodes, G.; Parker, S.E.; Murphy, M.; Atkins, G.J.; Liljeström, P. Self-replicative RNA vaccines elicit protection against influenza A virus, respiratory syncytial virus, and a tickborne encephalitis virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2001, 183, 1395–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.Z.; Guo, J.P.; An, H.J.; Zhang, S.M.; Wang, S.; Yu, W.Y.; Sun, Z.W. Potent tetravalent replicon vaccines against botulinum neurotoxins using DNA-based Semliki Forest virus replicon vectors. Vaccine 2013, 31, 2427–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xiao, S.; Fang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, H. Enhanced immunogenicity to food-and-mouth disease virus in mice vaccination with alphaviral replicon-based DNA vaccine expressing the capsid precursor polypeptide (P1). Virus Genes 2006, 33, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Qiu, H.-J.; Zhao, J.-J.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.-J.; Lu, B.-W.; Han, C.-G.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Z.-H.; Gao, H.; et al. A Semliki Forest virus replicon vectored DNA vaccine expressing the E2 glycoprotein of classical swine fever virus protects pigs from lethal challenge. Vaccine 2007, 25, 2907–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Jin, N.; Liu, Q.; Huo, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, B.; Ma, H.; Zhu, Z.; Cong, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Semliki forest virus replicon-based DNA vaccines encoding goatpox virus structural proteins. Virology 2009, 391, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).