Soil Nitrogen Mineralization Is Driven by Functional Microbiomes Across a North–South Forest in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Field Sampling

2.2. Analysis of Soil Properties

2.3. Determination of Potential Net N Mineralization Rate (NMR)

2.4. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.5. Metagenomics Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

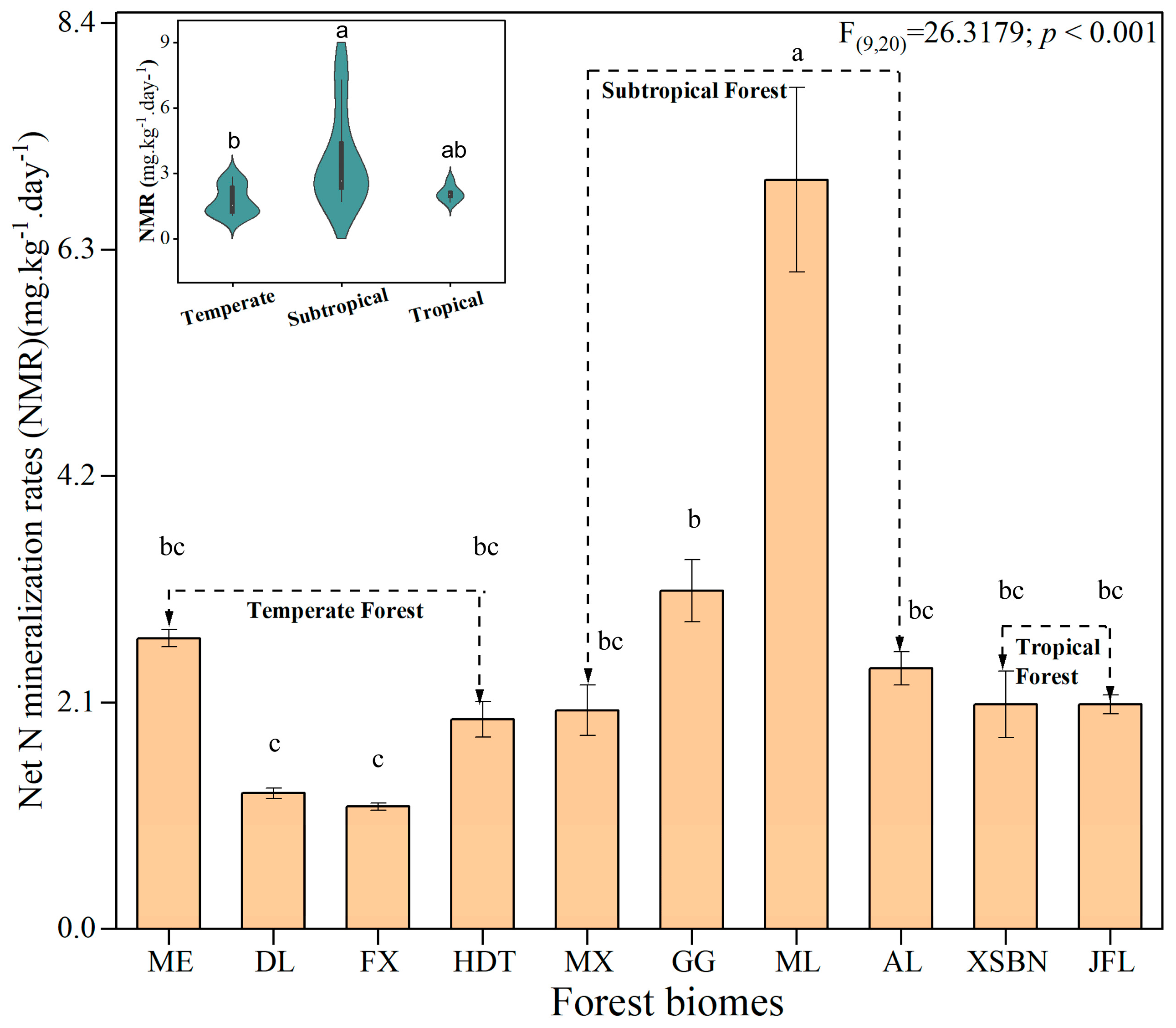

3.1. Changes in Soil Substrates and Net N Mineralization Rates

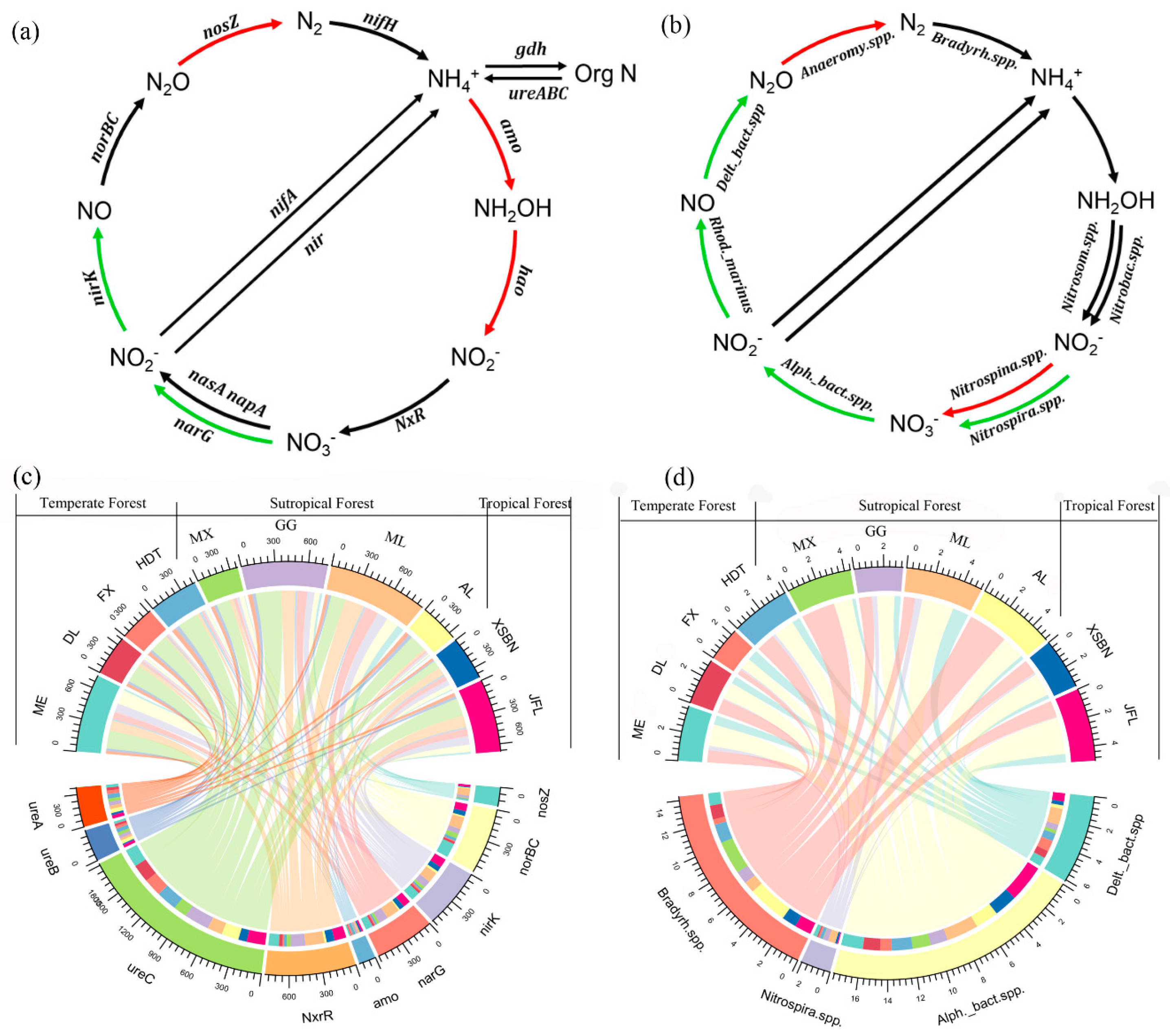

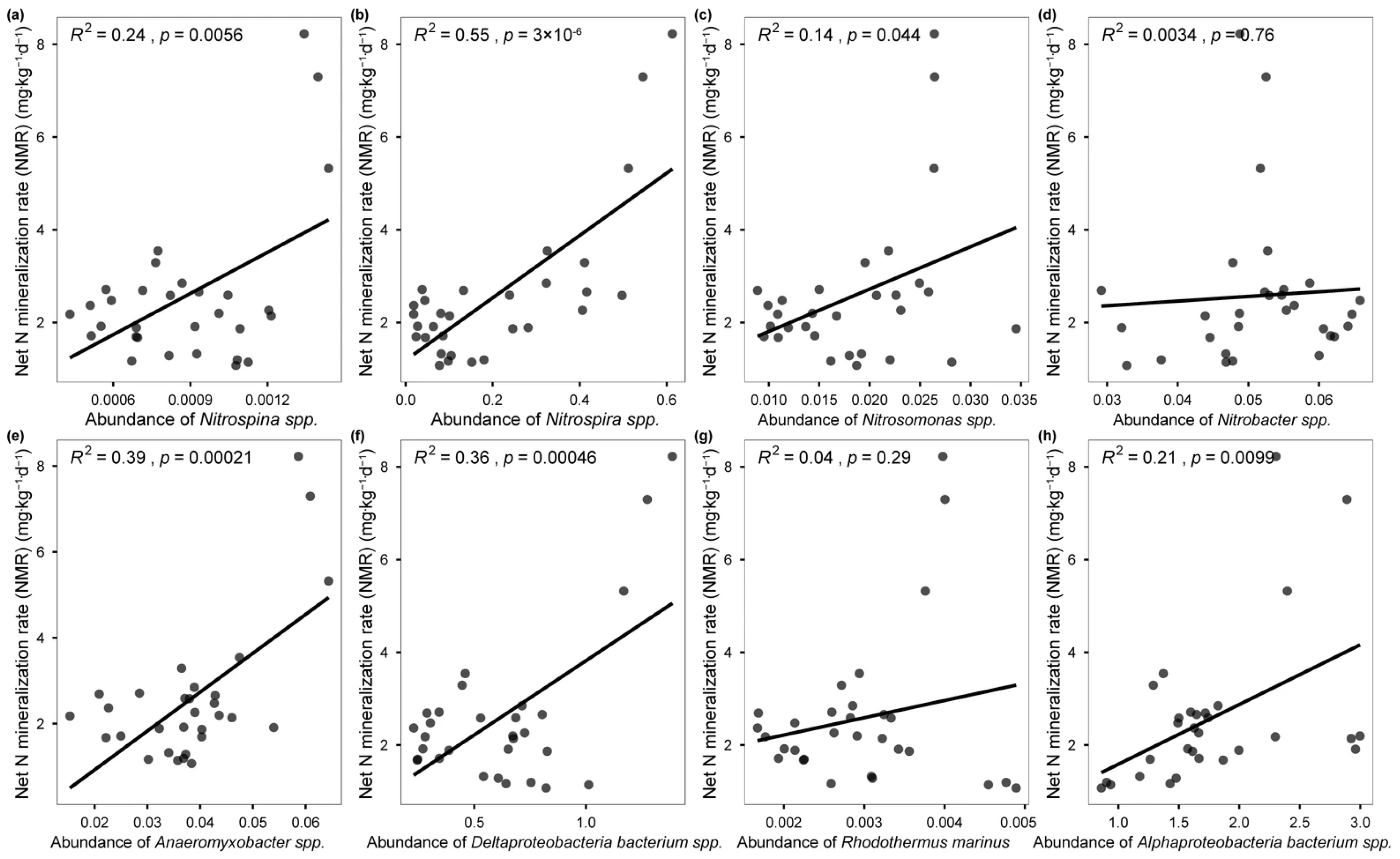

3.2. Changes in Microbial N-Cycling Genes and Species

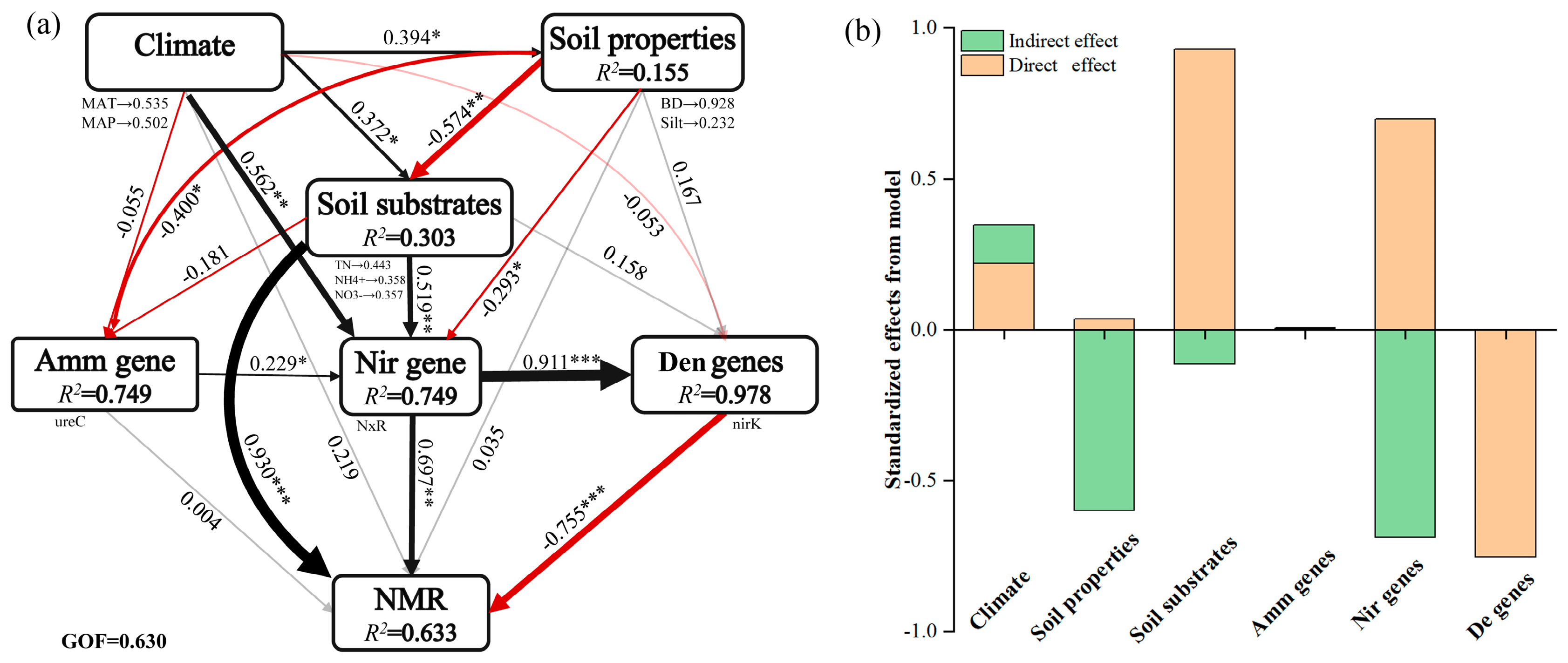

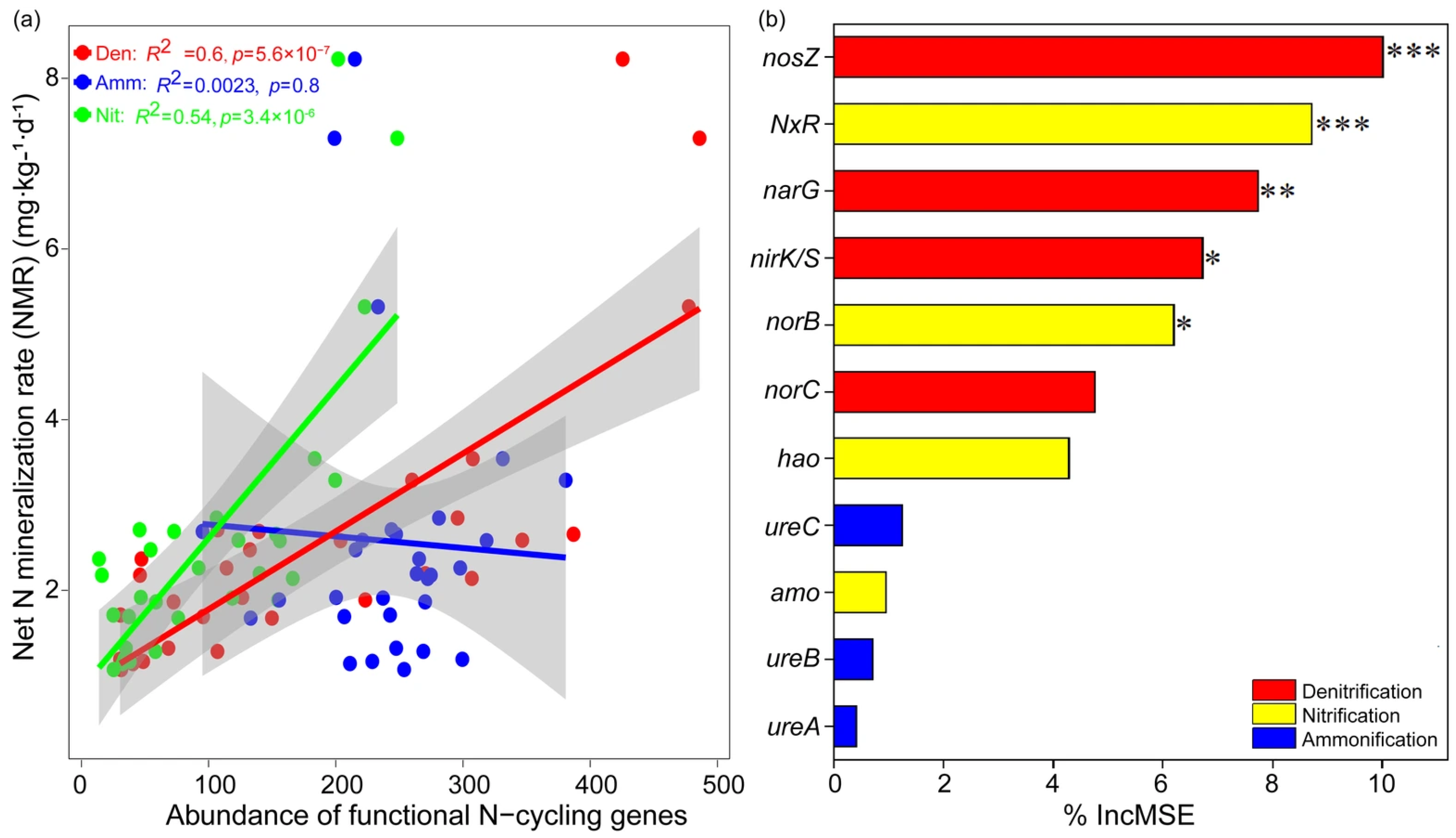

3.3. Microbial N-Cycling Traits Explain a Unique Portion of Variation in Soil NMR

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil N Mineralization Ratio in Forests Across Biomes

4.2. Spatial Patterns of Microbial N-Cycling Traits and Their Controls on Soil NMR in Forests Across Biomes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMR | N mineralization rates |

| SOC | soil organic C |

| TN | total N |

| MAT | mean annual temperature |

| MAP | mean annual precipitation |

| BD | soil bulk density |

References

- Nelson, M.B.; Martiny, A.C.; Martiny, J.B.H. Global biogeography of microbial nitrogen-cycling traits in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Xiao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Liu, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, D.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, W. Long-term manuring enhances soil gross nitrogen mineralization and ammonium immobilization in subtropical area. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 348, 108439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Searle, E.B.; Chen, C.; Reich, P.B. Negative to positive shifts in diversity effects on soil nitrogen over time. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, C.C.; Houlton, B.Z.; Smith, W.K.; Marklein, A.R.; Reed, S.C.; Parton, W.; Del Grosso, S.J.; Running, S.W. Patterns of new versus recycled primary production in the terrestrial biosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 12733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Tian, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Chen, H.Y.H.; Quan, Q.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Meng, C.; et al. Global variations and controlling factors of soil nitrogen turnover rate. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 207, 103250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achat, D.L.; Augusto, L.; Gallet-Budynek, A.; Loustau, D. Future challenges in coupled c–n–p cycle models for terrestrial ecosystems under global change: A review. Biogeochemistry 2016, 131, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Vitousek, P.M.; Mao, Q.; Gilliam, F.S.; Luo, Y.; Turner, B.L.; Zhou, G.; Mo, J. Nitrogen deposition accelerates soil carbon sequestration in tropical forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020790118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, C.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Hamonts, K.; Lai, K.T.; Reich, P.B.; Singh, B.K. Losses in microbial functional diversity reduce the rate of key soil processes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, C.; Reich, P.B.; Maestre, F.T.; Hu, H.W.; Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Plant-driven niche differentiation of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in global drylands. ISME J. 2019, 13, 2727–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Sun, S.; Medina-Roldán, E.; Zhao, S.; Hu, Y.; Guo, A.; Zuo, X. Soil net nitrogen transformation rates are co-determined by multiple factors during the landscape evolution in horqin sandy land. CATENA 2021, 206, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntiñas, M.E.; Leirós, M.C.; Trasar-Cepeda, C.; Gil-Sotres, F. Effects of moisture and temperature on net soil nitrogen mineralization: A laboratory study. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2012, 48, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyissa, A.; Yang, F.; Wu, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, X. Soil nitrogen dynamics at a regional scale along a precipitation gradient in secondary grassland of china. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, N.; Wen, X.; Yu, G.; Gao, Y.; Jia, Y. Patterns and regulating mechanisms of soil nitrogen mineralization and temperature sensitivity in chinese terrestrial ecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 215, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, E.; Li, S.; Xu, W.; Li, W.; Dai, W.; Jiang, P. A meta-analysis of experimental warming effects on terrestrial nitrogen pools and dynamics. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; He, N.; Wen, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Niu, S.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Luo, Y.; Yu, G. A global synthesis of the rate and temperature sensitivity of soil nitrogen mineralization: Latitudinal patterns and mechanisms. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séneca, J.; Pjevac, P.; Canarini, A.; Herbold, C.W.; Zioutis, C.; Dietrich, M.; Simon, E.; Prommer, J.; Bahn, M.; Pötsch, E.M.; et al. Composition and activity of nitrifier communities in soil are unresponsive to elevated temperature and CO2, but strongly affected by drought. ISME J. 2020, 14, 3038–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sinsabaugh, R.L. Linking microbial functional gene abundance and soil extracellular enzyme activity: Implications for soil carbon dynamics. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 27, 1322–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrinho, A.; Mendes, L.W.; Merloti, L.F.; Andreote, F.D.; Tsai, S.M. The natural recovery of soil microbial community and nitrogen functions after pasture abandonment in the amazon region. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiaa149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindlbacher, A.; Rodler, A.; Kuffner, M.; Kitzler, B.; Sessitsch, A.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Experimental warming effects on the microbial community of a temperate mountain forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xue, S.; Liu, G.B.; Song, Z.L. A comparison of soil qualities of different revegetation types in the loess plateau, China. Plant Soil 2011, 347, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of soils1. Agron. J. 1962, 54, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wan, S.; Xing, X.; Zhang, L.; Han, X. Temperature and soil moisture interactively affected soil net n mineralization in temperate grassland in northern China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. CUTADAPT removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.F.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Chen, Y.R.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, P.; Ng, K.L.; Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with kaiju. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.W. Megahit: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.H.; Lomsadze, A.; Borodovsky, M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karin, E.L.; Mirdita, M.; Soding, J. Metaeuk-sensitive, high-throughput gene discovery, and annotation for large-scale eukaryotic metagenomics. Microbiome 2020, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, J.; Töwe, S.; Bannert, A.; Hai, B.; Kastl, E.M.; Meyer, A.; Su, M.X.; Kleineidam, K.; Schloter, M. Nitrogen turnover in soil and global change. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 78, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Lauber, C.L.; Weintraub, M.N.; Ahmed, B.; Allison, S.D.; Crenshaw, C.; Contosta, A.R.; Cusack, D.; Frey, S.; Gallo, M.E.; et al. Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Schlaeppi, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Keystone taxa as drivers of microbiome structure and functioning. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rustad, L.; Campbell, J.; Marion, G.; Norby, R.; Mitchell, M.; Hartley, A.; Cornelissen, J.; Gurevitch, J.; Gcte, N. A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia 2001, 126, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Chen, H.Y.H. Plant diversity loss reduces soil respiration across terrestrial ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zak, D.R.; Holmes, W.E.; White, D.C.; Peacock, A.D.; Tilman, D. Plant diversity, soil microbial communities, and ecosystem function: Are there any links? Ecology 2003, 84, 2042–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.U.; Vitousek, P.M. Effects of plant composition and diversity on nutrient cycling. Ecol. Monogr. 1998, 68, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, Y.; Doughty, C.; Galbraith, D. The allocation of ecosystem net primary productivity in tropical forests. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2011, 366, 3225–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, D.M.; Wrage, N.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Pfeffer, M.; Brus, D.; Oenema, O.; Van Groenigen, J.W. Nitrifier denitrification can be a source of n2o from soil: A revised approach to the dual-isotope labelling method. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2010, 61, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.; Cruz-García, C.; Sanford, R.; Ritalahti, K.M.; Löffler, F.E. Denitrification versus respiratory ammonification: Environmental controls of two competing dissimilatory NO3−/NO2− reduction pathways in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumft, W.G. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61, 533–616. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin, R.J.; Stevens, R.J. Evidence for fungal dominance of denitrification and codenitrification in a grassland soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 1540–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daims, H.; Lebedeva, E.V.; Pjevac, P.; Han, P.; Herbold, C.; Albertsen, M.; Jehmlich, N.; Palatinszky, M.; Vierheilig, J.; Bulaev, A.; et al. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 2015, 528, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkelmann, D.; Schneider, D.; Meryandini, A.; Daniel, R. Unravelling the effects of tropical land use conversion on the soil microbiome. Environ. Microbiome 2020, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Nuccio, E.E.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, N.; Xue, K.; Cohan, F.M.; Zhou, J.; Sun, B. Differentiation strategies of soil rare and abundant microbial taxa in response to changing climatic regimes. Environ. Microbiome 2020, 22, 1327–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, H.; Yuan, M.; Ren, C.; Zhao, F.; Wang, J. Soil Nitrogen Mineralization Is Driven by Functional Microbiomes Across a North–South Forest in China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122799

Cheng H, Yuan M, Ren C, Zhao F, Wang J. Soil Nitrogen Mineralization Is Driven by Functional Microbiomes Across a North–South Forest in China. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122799

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Hongyan, Minshu Yuan, Chengjie Ren, Fazhu Zhao, and Jun Wang. 2025. "Soil Nitrogen Mineralization Is Driven by Functional Microbiomes Across a North–South Forest in China" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122799

APA StyleCheng, H., Yuan, M., Ren, C., Zhao, F., & Wang, J. (2025). Soil Nitrogen Mineralization Is Driven by Functional Microbiomes Across a North–South Forest in China. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2799. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122799