Role of Genomic, Economic, and Demographic Disparities in Mpox Epidemic in Africa: A Retrospective Cross-Country Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Analytical Strategy

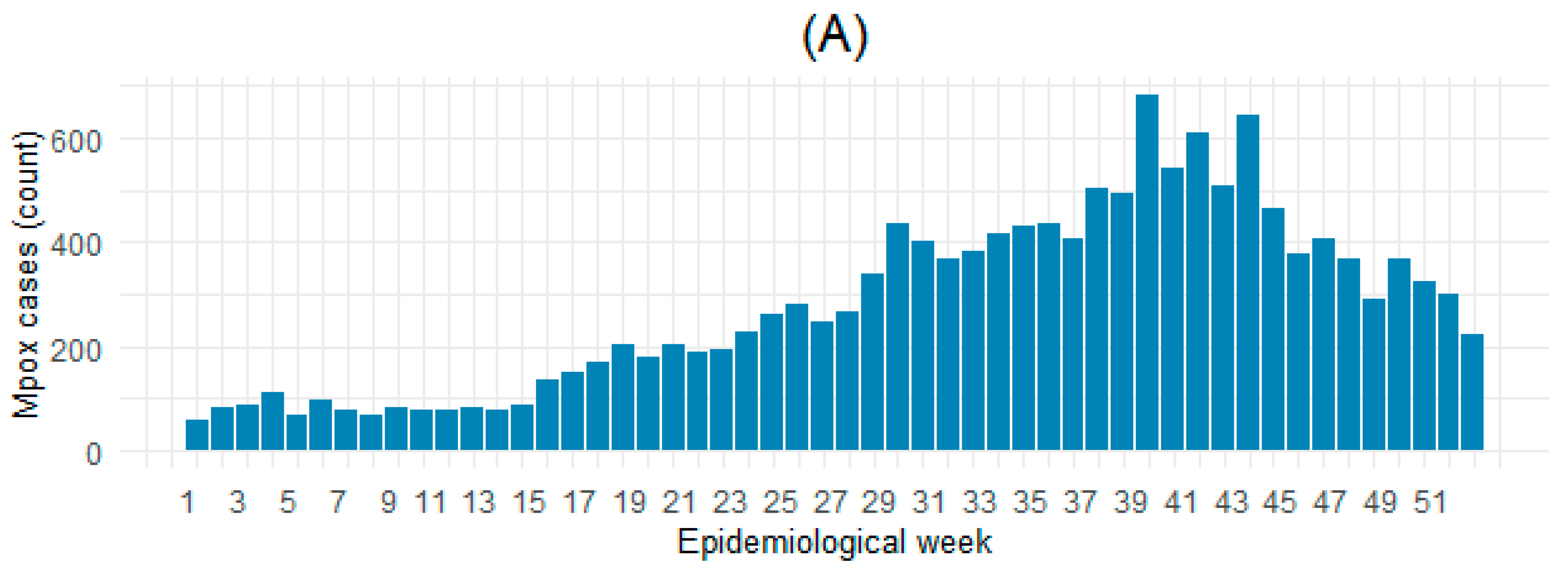

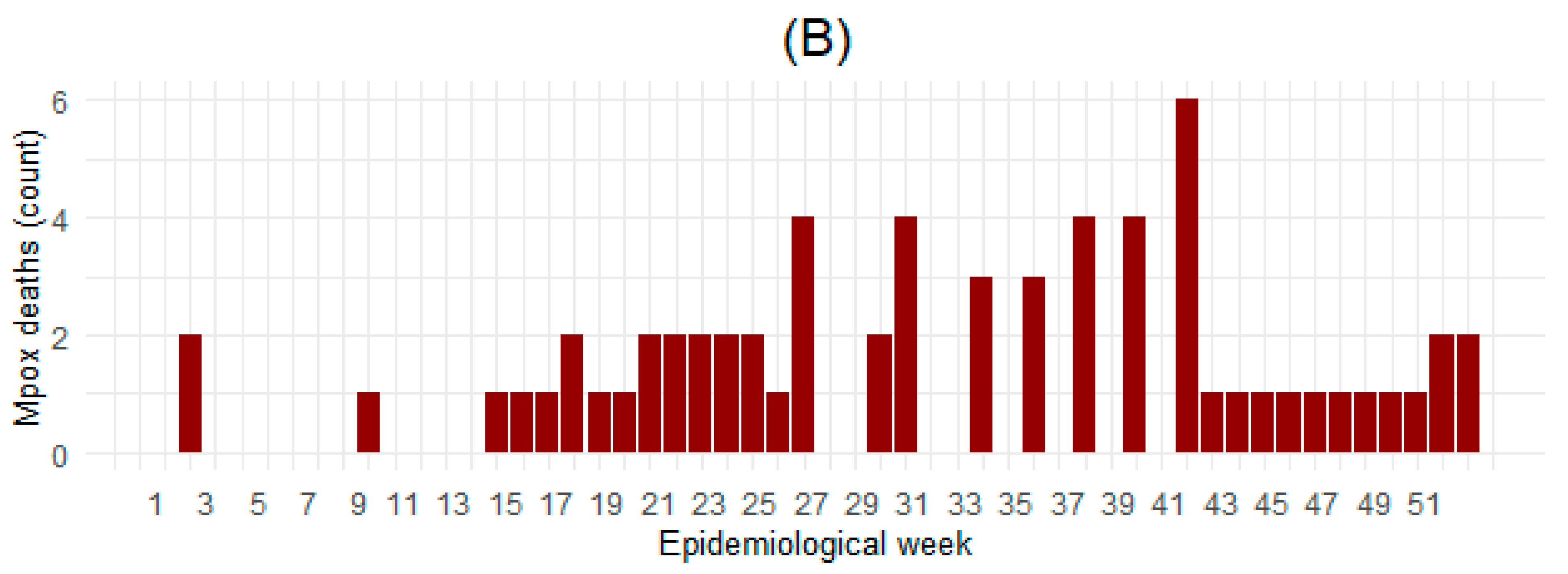

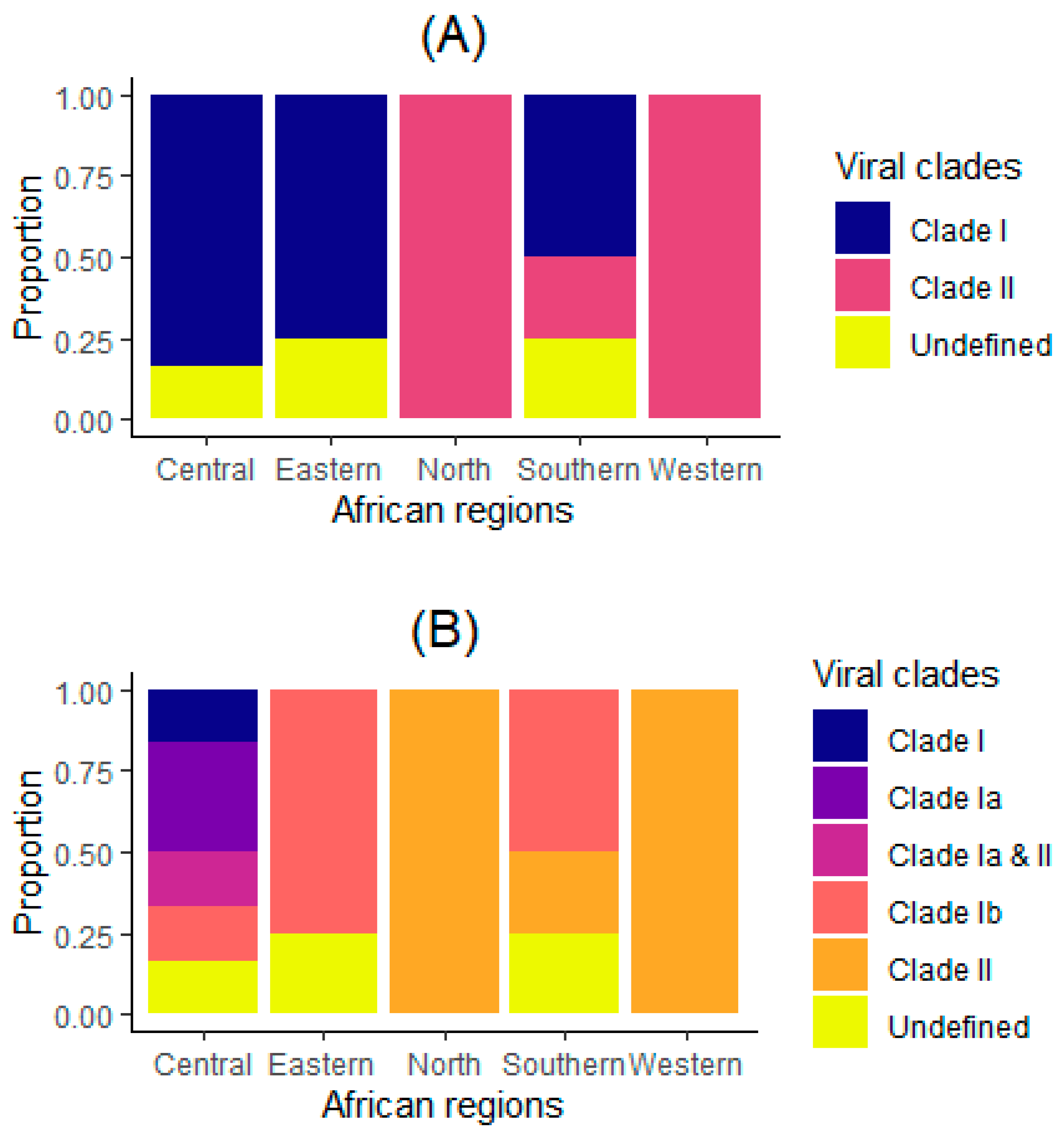

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Analyzed Countries

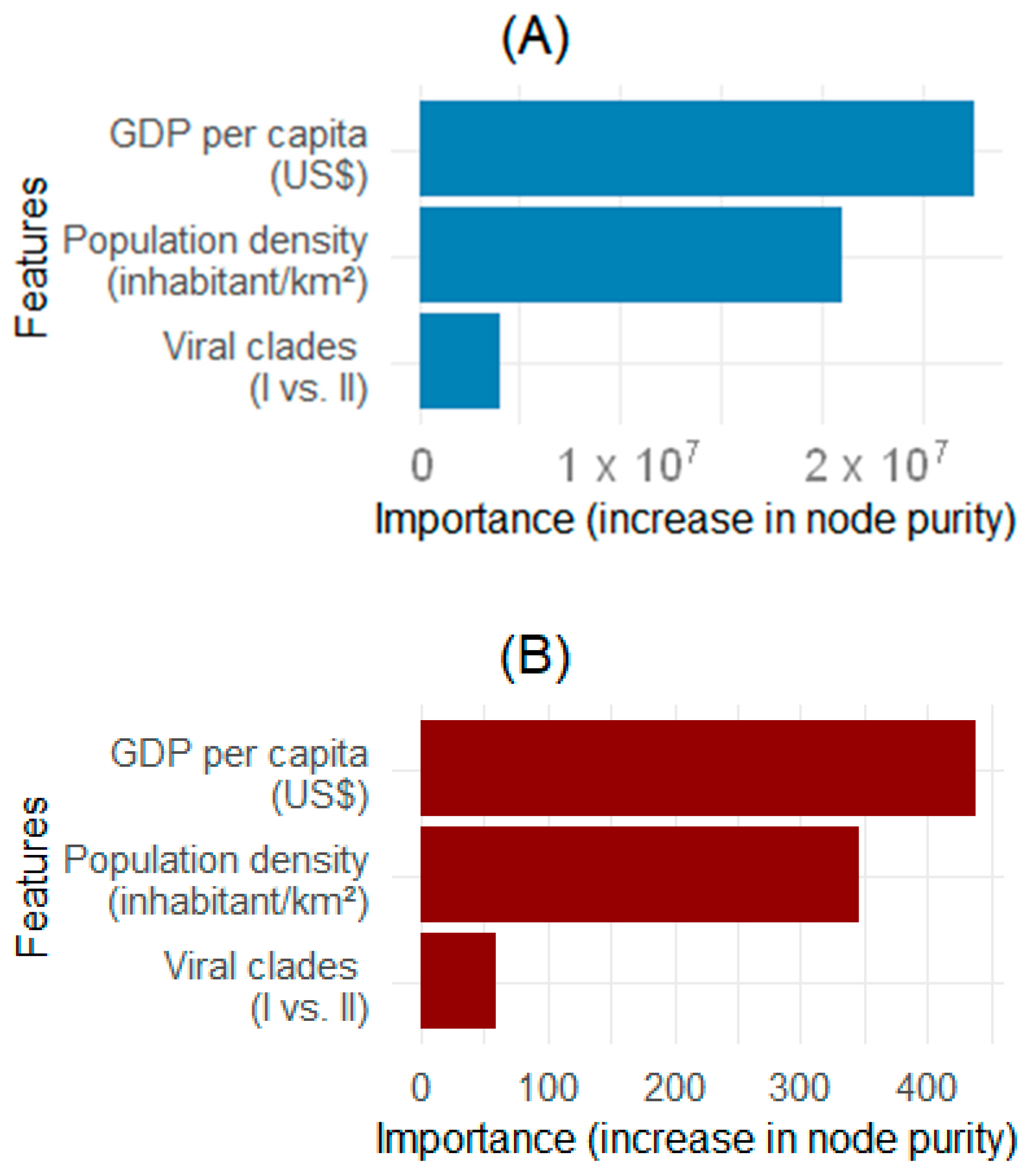

3.2. Identification of Factors Associated with the Mpox Epidemic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| CFR | Case fatality rate |

| MoH | Ministry of Health |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of Congo |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| NBR | Negative binomial regression |

| IRR | Incidence rate ratio |

References

- Kaler, J.; Hussain, A.; Flores, G.; Kheiri, S.; Desrosiers, D. Monkeypox: A Comprehensive Review of Transmission, Pathogenesis, and Manifestation. Cureus 2022, 14, e26531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhn, G.D.; Bauer, A.M.; Yorita, K.; Graham, M.B.; Sejvar, J.; Likos, A.; Damon, I.K.; Reynolds, M.G.; Kuehnert, M.J. Clinical Characteristics of Human Monkeypox, and Risk Factors for Severe Disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 1742–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, R.K.; Tuli, H.S.; Sarangi, A.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Chandran, D.; Chakraborty, C.; Dhama, K. Unexpected Sudden Rise of Human Monkeypox Cases in Multiple Non-Endemic Countries amid COVID-19 Pandemic and Salient Counteracting Strategies: Another Potential Global Threat? Int. J. Surg. Lond. Engl. 2022, 103, 106705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheek-Hussein, M.; Alsuwaidi, A.R.; Davies, E.A.; Abu-Zidan, F.M. Monkeypox: A Current Emergency Global Health Threat. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 005–016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Xu, A.; Guan, L.; Tang, Y.; Chai, G.; Feng, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; et al. A Review of Mpox: Biological Characteristics, Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention Strategies. Exploration 2025, 5, 20230112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoin, A.W.; Mulembakani, P.M.; Johnston, S.C.; Lloyd Smith, J.O.; Kisalu, N.K.; Kinkela, T.L.; Blumberg, S.; Thomassen, H.A.; Pike, B.L.; Fair, J.N.; et al. Major Increase in Human Monkeypox Incidence 30 Years after Smallpox Vaccination Campaigns Cease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16262–16267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, K.; Heymann, D.; Brown, C.S.; Edmunds, W.J.; Elsgaard, J.; Fine, P.; Hochrein, H.; Hoff, N.A.; Green, A.; Ihekweazu, C.; et al. Human Monkeypox—After 40 Years, an Unintended Consequence of Smallpox Eradication. Vaccine 2020, 38, 5077–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization WHO Director-General Declares Mpox Outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Jamil, H.; Tariq, W.; Tahir, M.J.; Mahfooz, R.S.; Asghar, M.S.; Ahmed, A. Human Monkeypox Expansion from the Endemic to Non-Endemic Regions: Control Measures. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 79, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufrénot, G.; Gallic, E.; Michel, P.; Bonou, N.M.; Gnaba, S.; Slaoui, I. Impact of Socioeconomic Determinants on the Speed of Epidemic Diseases: A Comparative Analysis. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2024, 76, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backer, S.; Rezene, A.; Kahar, P.; Khanna, D. Socioeconomic Determinants of COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality in Florida. Cureus 2022, 14, e22491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Broecke, B.; Mariën, J.; Sabuni, C.A.; Mnyone, L.; Massawe, A.W.; Matthysen, E.; Leirs, H. Relationship between Population Density and Viral Infection: A Role for Personality? Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 10213–10224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likos, A.M.; Sammons, S.A.; Olson, V.A.; Frace, A.M.; Li, Y.; Olsen-Rasmussen, M.; Davidson, W.; Galloway, R.; Khristova, M.L.; Reynolds, M.G.; et al. A Tale of Two Clades: Monkeypox Viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 2661–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musuka, G.; Moyo, E.; Tungwarara, N.; Mhango, M.; Pierre, G.; Saramba, E.; Iradukunda, P.G.; Dzinamarira, T. A Critical Review of Mpox Outbreaks, Risk Factors, and Prevention Efforts in Africa: Lessons Learned and Evolving Practices. IJID Reg. 2024, 12, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazarie, S.; Soriano-Paños, D.; Arenas, A.; Gómez-Gardeñes, J.; Ghoshal, G. Interplay between Population Density and Mobility in Determining the Spread of Epidemics in Cities. Commun. Phys. 2021, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, A.M.; Damon, I.K. Human Monkeypox. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, H.; Idrees, M.; Idrees, K.; Tariq, W.; Sayyeda, Q.; Asghar, M.S.; Tahir, M.J.; Akram, S.; Ullah, K.; Ahmed, A.; et al. Socio-Demographic Determinants of Monkeypox Virus Preventive Behavior: A Cross-Sectional Study in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Surveillance, Case Investigation and Contact Tracing for Monkeypox: Interim Guidance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MPX-Surveillance-2024.1 (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- World Bank World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- McQuiston, J.H. U.S. Preparedness and Response to Increasing Clade I Mpox Cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo —United States, 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibungu, E.M.; Vakaniaki, E.H.; Kinganda-Lusamaki, E.; Kalonji-Mukendi, T.; Pukuta, E.; Hoff, N.A.; Bogoch, I.I.; Cevik, M.; Gonsalves, G.S.; Hensley, L.E.; et al. Clade I—Associated Mpox Cases Associated with Sexual Contact, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieleman, J.L.; Campbell, M.; Chapin, A.; Eldrenkamp, E.; Fan, V.Y.; Haakenstad, A.; Kates, J.; Li, Z.; Matyasz, T.; Micah, A.; et al. Future and Potential Spending on Health 2015–40: Development Assistance for Health, and Government, Prepaid Private, and out-of-Pocket Health Spending in 184 Countries. Lancet 2017, 389, 2005–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A.; Neelsen, S. A Comprehensive Assessment of Universal Health Coverage in 111 Countries: A Retrospective Observational Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e39–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, J.P.; Simões, D.G.; Aguiar, P. Impact of Sociodemographic and Economic Determinants of Health on COVID-19 Infection: Incidence Variation between Reference Periods. Public Health 2023, 225, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Q.; Han, J. Preparedness for a Monkeypox Outbreak. Infect. Med. 2022, 1, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The Changing Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox—A Potential Threat? A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernstrom, A.; Goldblatt, M. Aerobiology and Its Role in the Transmission of Infectious Diseases. J. Pathog. 2013, 2013, 493960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Nigmatulina, K.; Eckhoff, P. The Scaling of Contact Rates with Population Density for the Infectious Disease Models. Math. Biosci. 2013, 244, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagliardo, S.A.J.; Doshi, R.H.; Reynolds, M.G.; Dzabatou-Babeaux, A.; Ndakala, N.; Moses, C.; McCollum, A.M.; Petersen, B.W. Do Monkeypox Exposures Vary by Ethnicity? Comparison of Aka and Bantu Suspected Monkeypox Cases. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehouse, E.R.; Bonwitt, J.; Hughes, C.M.; Lushima, R.S.; Likafi, T.; Nguete, B.; Kabamba, J.; Monroe, B.; Doty, J.B.; Nakazawa, Y.; et al. Clinical and Epidemiological Findings from Enhanced Monkeypox Surveillance in Tshuapa Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo During 2011–2015. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, 1870–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | No. (%) | Median (IQR) [Min; Max] |

|---|---|---|

| Reporting weeks (count) a | 278 | 10.0 (2.5; 22.5) [1.0; 46.0] |

| Cases (count) a | 14,570 | 24.5 (3.0; 98.5) [1.0; 9513.0] |

| Deaths (count) a | 64 | 0.0 (0.0; 1.0) [0.0; 43.0] |

| GDP per capita (US $) | 20 | 1844.6 (1006.3; 2504.4) [109.0; 11,623.0] |

| Population density (inhabitant/km2) | 20 | 72.1 (43.0; 171.8) [8.3; 618.1] |

| Viral clades (n = 20) | ||

| Clade I | 10 (50) | NA |

| Clade II | 7 (35) | NA |

| Undefined | 3 (15) | NA |

| Viral subclades (n = 20) | ||

| Clade I | 1 (5) | NA |

| Clade Ia | 2 (10) | NA |

| Clade Ia & II | 1 (5) | NA |

| Clade Ib | 6 (30) | NA |

| Clade II | 7 (35) | NA |

| Undefined | 3 (15) | NA |

| Regions (n = 20) | ||

| Central | 6 (30) | NA |

| Eastern | 4 (20) | NA |

| North | 1 (5) | NA |

| Southern | 4 (20) | NA |

| Western | 5 (25) | NA |

| Epidemic Determinants | Mpox Cases | Mpox Deaths | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR [95% CI] | p-Value | IRR [95% CI] | p-Value | |

| GDP per capita (per US $1000 increase) | 0.53 [0.38–0.74] | <0.001 | 0.93 [0.53–1.65] | 0.813 |

| Population density (per 100-unit increase) | 1.00 [0.59–1.70] | 0.989 | 0.55 [0.16–1.17] | 0.119 |

| Viral clade | ||||

| Clade I (reference) | 1 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.110 |

| Clade II | 0.15 [0.02–0.97] | 0.93 [0.01–1.72] | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kayembe-Mulumba, B.; N’gattia, A.K.; Belizaire, M.R.D.; Koyazegbe, T.D.; Simaleko, M.M.; Boum, Y., II; Somsé, P. Role of Genomic, Economic, and Demographic Disparities in Mpox Epidemic in Africa: A Retrospective Cross-Country Analysis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2531. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112531

Kayembe-Mulumba B, N’gattia AK, Belizaire MRD, Koyazegbe TD, Simaleko MM, Boum Y II, Somsé P. Role of Genomic, Economic, and Demographic Disparities in Mpox Epidemic in Africa: A Retrospective Cross-Country Analysis. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(11):2531. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112531

Chicago/Turabian StyleKayembe-Mulumba, Blondy, Anderson Kouabenan N’gattia, Marie Roseline Darnycka Belizaire, Thomas D’Aquin Koyazegbe, Marcel Mbeko Simaleko, Yap Boum, II, and Pierre Somsé. 2025. "Role of Genomic, Economic, and Demographic Disparities in Mpox Epidemic in Africa: A Retrospective Cross-Country Analysis" Microorganisms 13, no. 11: 2531. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112531

APA StyleKayembe-Mulumba, B., N’gattia, A. K., Belizaire, M. R. D., Koyazegbe, T. D., Simaleko, M. M., Boum, Y., II, & Somsé, P. (2025). Role of Genomic, Economic, and Demographic Disparities in Mpox Epidemic in Africa: A Retrospective Cross-Country Analysis. Microorganisms, 13(11), 2531. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13112531