Essential Oils as a Novel Anti-Biofilm Strategy Against Salmonella Enteritidis Isolated from Chicken Meat

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates

2.2. Essential Oils

2.3. Biofilm Formation

2.4. Biofilm Reduction

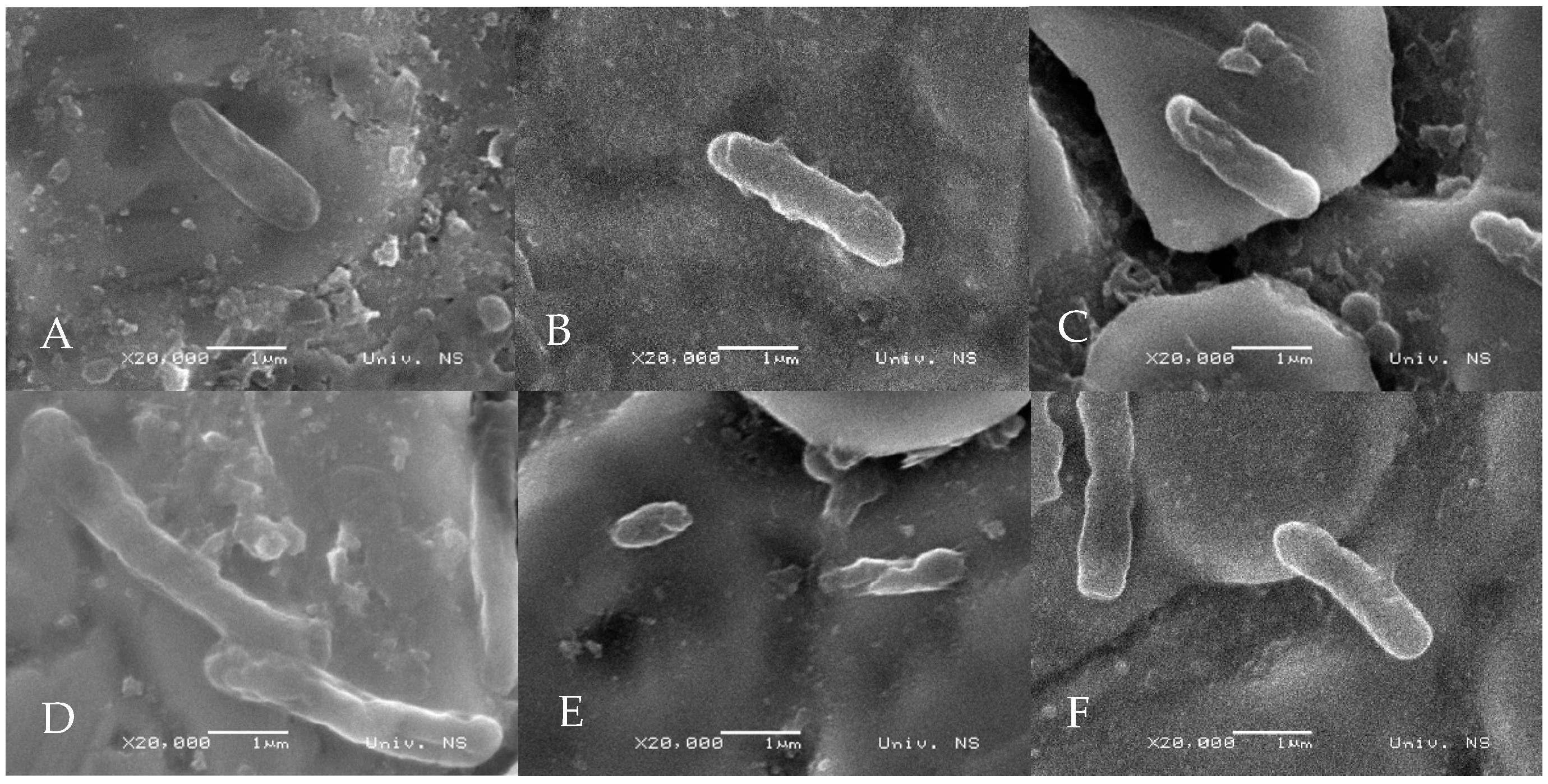

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Salmonella Enteritidis Biofilm Formation

3.2. Salmonella Enteritidis Biofilm Reduction

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy Observation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar]

- Steenackers, H.; Hermans, K.; Vanderleyden, J.; De Keersmaecker, S.C. Salmonella biofilms: An overview on occurrence, structure, regulation and eradication. Food Res. Int. 2012, 45, 502–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrowicz, A.; Carolak, E.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Błachut, A.; Waszczuk, W.; Grzymajlo, K. Better together—Salmonella biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2229937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tee, X.W.; Abdul-Mutalib, N.A. Salmonella Biofilm on Food Contact Surfaces and the Efficacy of Chemical Disinfectants: A Systematic Review. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 31, 2187–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.; Chaves-López, C.; Serio, A.; Casaccia, M.; Maggio, F.; Paparella, A. Effectiveness and mechanisms of essential oils for biofilm control on food-contact surfaces: An updated review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 2172–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, F.; Rossi, C.; Serio, A.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Casaccia, M.; Paparella, A. Anti-biofilm mechanisms of action of essential oils by targeting genes involved in quorum sensing, motility, adhesion, and virulence: A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 426, 110874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaković Knežević, S.; Knežević, S.; Vranešević, J.; Kravić, S.Ž.; Lakićević, B.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Karabasil, N. Effects of Selected Essential Oils on Listeria monocytogenes in Biofilms and in a Model Food System. Foods 2023, 12, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S. Essential oils: Their antibacterial properties and potential applications in foods—A review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 94, 223–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johny, A.K.; Darre, M.J.; Donoghue, A.M.; Donoghue, D.J.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Antibacterial effect of trans-cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, carvacrol, and thymol on Salmonella Enteritidis and Campylobacter jejuni in chicken cecal contents in vitro. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2010, 19, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Değirmenci, H.; Erkurt, H. Relationship between volatile components, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of the essential oil, hydrosol and extracts of Citrus aurantium L. flowers. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaković Knežević, S.; Knežević, S.; Vranešević, J.; Milanov, D.; Ružić, Z.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Karabasil, N. Using Essential Oils to Reduce Yersinia enterocolitica in Minced Meat and in Biofilms. Foods 2024, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posgay, M.; Greff, B.; Kapcsándi, V.; Lakatos, E. Effect of Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil and thymol on the microbiological properties of meat and meat products: A review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, Y.; Dong, P.; Ni, L.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L. Inhibitory effects of clove and oregano essential oils on biofilm formation of Salmonella Derby isolated from beef processing plant. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2022, 162, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, K.P.; Nisha, S.A.; Sakthivel, R.; Pandian, S.K. Eugenol (an essential oil of clove) acts as an antibacterial agent against Salmonella typhi by disrupting the cellular membrane. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurzyńska-Wierdak, R. Antibiofilm Potential of Natural Essential Oils. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.; Dos Santos, A.R.; Trevisan, D.A.C.; Ribeiro, A.B.; Campanerut-Sá, P.A.Z.; Kukolj, C.; de Souza, E.M.; Cardosa, R.F.; Svidzinski, T.I.E.; de Abreu Filho, B.A.; et al. Cinnamaldehyde induces changes in the protein profile of Salmonella Typhimurium biofilm. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6579-1:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO/TR 6579-3:2014; Microbiology of the Food Chain-Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella—Part 3: Guidelines for Serotyping of Salmonella spp. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- FDA. 2025 21 CFR Chapter I Subchapter B. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Vidaković Knežević, S.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Kravić, S.; Knežević, S.; Vranešević, J.; Savić Radovanović, R.; Karabasil, N. In vitro antibacterial activity of some essential oils against Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium isolated from meat. J. Food Saf. Food Qual. 2021, 72, 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Blagojev, N.; Suturović, I.; Dimić, G.; Pejin, J.; Tomović, V.; Šojić, B.; Savanović, J.; Kravić, S.; Karabasil, N. Antibacterial activity essential oils against Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica and Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Saf. Food Qual. 2017, 68, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanović, S.; Vuković, D.; Hola, V.; Bonaventura, G.D.; Djukić, S.; Ćirković, I.; Ruzicka, F. Quantification of biofilm in microtiter plates: Overview of testing conditions and practical recommendations for assessment of biofilm production by staphylococci. APMIS J. Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 115, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillaci, D.; Arizza, V.; Dayton, T.; Camarda, L.; Stefano, V.D. In vitro anti-biofilm activity of Boswellia spp. oleogum resin essential oils. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanović, S.; Ćirković, I.; Ranin, L.; Švabić-Vlahović, M. Biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes on plastic surface. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 38, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, B.; Corbo, M.R.; Sinigaglia, M. Effects of nutritional and environmental conditions on Salmonella sp. biofilm formation. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, M12–M16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatila, F.; Yaşa, İ.; Yalçın, H.T. Biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica strains. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-García, M.; Capita, R.; Alonso-Calleja, C. Influence of serotype on the growth kinetics and the ability to form biofilms of Salmonella isolates from poultry. Food Microbiol. 2012, 31, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hue, O.; Le Bouquin, S.; Laisney, M.J.; Allain, V.; Lalande, F.; Petetin, I.; Chemaly, M.; Rouxel, S.; Quesne, S.; Gloaguen, P.-Y.; et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for Campylobacter spp. contamination of broiler chicken carcasses at the slaughterhouse. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 992–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biglia, A.; Gemmell, A.J.; Foster, H.J.; Evans, J.A. Temperature and energy performance of domestic cold appliances in households in England. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 87, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, K.A.; Furian, T.Q.; Souza, S.N.; Menezes, R.; Tondo, E.C.; Salle, C.T.; Nascimento, V.P.; Moraes, H.L. Biofilm formation capacity of Salmonella serotypes at different temperature conditions. Pesqui. Vet. Bras. 2018, 38, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, D.C.V.; Fernandes Júnior, A.; Kaneno, R.; Silva, M.G.; Araújo Júnior, J.P.; Silva, N.C.C.; Rall, V.L.M. Ability of Salmonella spp. to produce biofilm is dependent on temperature and surface material. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2014, 11, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanović, S.; Ćirković, I.; Mijač, V.; Švabić-Vlahović, M. Influence of the incubation temperature, atmosphere and dynamic conditions on biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. Food Microbiol. 2003, 20, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, F.; Fois, F.; Consolati, S.G.; Mazza, R.; Mazzette, R. Influence of temperature, source, and serotype on biofilm formation of Salmonella enterica isolates from pig slaughterhouses. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 1875–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, R.J.W.; Skandamis, P.N.; Coote, P.J.; Nychas, G.J.E. A study of the minimum inhibitory concentration and mode of action of oregano essential oil, thymol and carvacrol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyldgaard, M.; Mygind, T.; Meyer, R.L. Essential oils in food preservation: Mode of action, synergies, and interactions with food matrix components. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memar, M.Y.; Raei, P.; Alizadeh, N.; Akbari, A.M.; Kafil, H.S. Carvacrol and thymol: Strong antimicrobial agents against resistant isolates. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 28, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, H.; Baysal, A.H. Antibacterial and antioxidant activity of essential oil terpenes against pathogenic and spoilage-forming bacteria and cell structure-activity relationships evaluated by SEM microscopy. Molecules 2014, 19, 17773–17798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachur, K.; Suntres, Z. The antibacterial properties of phenolic isomers, carvacrol and thymol. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2020, 60, 3042–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.E.; Maillard, J.Y.; Russell, A.D.; Catrenich, C.E.; Charbonneau, D.L.; Bartolo, R.G. Activity and mechanisms of action of selected biocidal agents on Gram-positive and -negative bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 94, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.K.; Kang, S.C. Thymol disrupts the membrane integrity of Salmonella ser. typhimurium in vitro and recovers infected macrophages from oxidative stress in an ex vivo model. Res. Microbiol. 2014, 165, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touati, A.; Mairi, A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Idres, T. Essential Oils for Biofilm Control: Mechanisms, Synergies, and Translational Challenges in the Era of Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, S.; Sharma, K.; Guleria, S. Antimicrobial activity of some essential oils—present status and future perspectives. Medicines 2017, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanla-Ead, N.; Jangchud, A.; Chonhenchob, V.; Suppakul, P. Antimicrobial Activity of cinnamaldehyde and eugenol and their activity after incorporation into cellulose-based packaging films. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2012, 25, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mith, H.; Dure, R.; Delcenserie, V.; Zhiri, A.; Daube, G.; Clinquart, A. Antimicrobial activities of commercial essential oils and their components against food-borne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 2, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Sana, A.M.; van Baren, C.M.; Elechosa, M.A.; Juárez, M.A.; Moreno, S. New insights into antibacterial and antioxidant activities of rosemary essential oils and their main components. Food Control. 2013, 31, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, C.; Lin, L. Antimicrobial mechanism of clove oil on Listeria monocytogenes. Food Control. 2018, 94, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultee, A.; Bennik, M.H.J.; Moezelaar, R. The phenolic hydroxyl group of carvacrol is essential for action against the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaimat, A.N.; Al-Holy, M.A.; Abu Ghoush, M.H.; Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Osaili, T.M.; Holley, R.A. Inhibitory effects of cinnamon and thyme essential oils against Salmonella spp. in hummus (chickpea dip). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e13925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Chen, K.; Yang, L.; Tang, T.; Jiang, S.; Guo, J.; Gao, Z. Essential oils from Citrus unshiu Marc. effectively kill Aeromonas hydrophila by destroying cell membrane integrity, influencing cell potential, and leaking intracellular substances. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 869953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginting, E.V.; Retnaningrum, E.; Widiasih, D.A. Antibacterial activity of clove (Syzygium aromaticum) and cinnamon (Cinnamomum burmannii) essential oil against extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria. Vet. World 2021, 14, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpena, M.; Nuñez-Estevez, B.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Prieto, M.A. Essential oils and their application on active packaging systems: A review. Resources 2021, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Essential Oils | Latin Name | Main Compounds (%) * | Minimal Bactericidal Concentrations (MBC) (µL/mL) * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE53 | SE56 | SE132 | SE144 | |||

| Oregano | Origanum vulgare | carvacrol (81.00%) | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Cinnamon | Cinnamomum zeylanicum Nees | cinnamaldehyde (74.93%) | 0.89 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| Rosemary | Rosmarinus officinalis | α-pinene (28.23%), borneol (24.87%) | 1.78 | 1.78 | 0.45 | 3.56 |

| Clove | Syzygium aromaticum L. | eugenol (85.14%) | 0.89 | 0.45 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Thyme | Thymus vulgaris | p-cymene (40.91%), thymol (40.36%) | 0.45 | 1.78 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Temperature (°C) | Nutrient Media | SE53 | SE56 | SE132 | SE144 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | TSB | 0.282 ± 0.061 ** | 0.291 ± 0.073 ** | 0.136 ± 0.013 * | 0.192 ± 0.034 * |

| MB | 0.185 ± 0.005 * | 0.215 ± 0.018 * | 0.215 ± 0.035 * | 0.174 ± 0.010 * | |

| LBB | 0.225 ± 0.014 * | 0.464 ± 0.062 ** | 0.481 ± 0.092 ** | 0.530 ± 0.084 *** | |

| 15 | TSB | 0.188 ± 0.010 * | 0.186 ± 0.011 * | 0.445 ± 0.087 ** | 0.163 ± 0.007 ° |

| MB | 0.173 ± 0.008 * | 0.210 ± 0.015 * | 0.191 ± 0.014 * | 0.162 ± 0.007 ° | |

| LBB | 0.240 ± 0.051 * | 0.196 ± 0.016 * | 0.406 ± 0.051 ** | 0.161 ± 0.017 * | |

| 5 | TSB | 0.247 ± 0.018 * | 0.222 ± 0.009 * | 0.187 ± 0.010 * | 0.159 ± 0.011 * |

| MB | 0.199 ± 0.025 * | 0.208 ± 0.020 * | 0.214 ± 0.025 * | 0.145 ± 0.006 ° | |

| LBB | 0.185 ± 0.015 * | 0.157 ± 0.014 * | 0.170 ± 0.014 * | 0.128 ± 0.009 * |

| Isolates | Conditions | Essential Oils | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oregano | Cinnamon | Rosemary | Clove | Thyme | ||

| SE53 | TSB/37 °C | 52.30 b | 45.09 a | 46.10 ab | 48.79 ab | 43.91 a |

| SE56 | TSB/37 °C | 53.81 a | 48.85 a | 53.09 a | 51.49 a | 48.42 a |

| SE56 | LBB/37 °C | 48.33 ab | 44.97 a | 50.14 ab | 55.62 b | 50.57 ab |

| SE132 | LBB/37 °C | 48.48 a | 42.33 a | 40.07 a | 44.68 a | 44.77 a |

| SE132 | TSB/15 °C | 74.83 b | 72.45 b | 65.75 a | 71.57 b | 72.79 b |

| SE132 | LBB/15 °C | 71.61 c | 60.14 b | 54.99 a | 70.83 c | 69.05 c |

| SE144 | LBB/37 °C | 47.06 b | 36.98 a | 50.86 bc | 58.18 c | 52.47 bc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vidaković Knežević, S.; Knežević, S.; Milanov, D.; Vranešević, J.; Pajić, M.; Kocić-Tanackov, S.; Karabasil, N. Essential Oils as a Novel Anti-Biofilm Strategy Against Salmonella Enteritidis Isolated from Chicken Meat. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102412

Vidaković Knežević S, Knežević S, Milanov D, Vranešević J, Pajić M, Kocić-Tanackov S, Karabasil N. Essential Oils as a Novel Anti-Biofilm Strategy Against Salmonella Enteritidis Isolated from Chicken Meat. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(10):2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102412

Chicago/Turabian StyleVidaković Knežević, Suzana, Slobodan Knežević, Dubravka Milanov, Jelena Vranešević, Marko Pajić, Sunčica Kocić-Tanackov, and Nedjeljko Karabasil. 2025. "Essential Oils as a Novel Anti-Biofilm Strategy Against Salmonella Enteritidis Isolated from Chicken Meat" Microorganisms 13, no. 10: 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102412

APA StyleVidaković Knežević, S., Knežević, S., Milanov, D., Vranešević, J., Pajić, M., Kocić-Tanackov, S., & Karabasil, N. (2025). Essential Oils as a Novel Anti-Biofilm Strategy Against Salmonella Enteritidis Isolated from Chicken Meat. Microorganisms, 13(10), 2412. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13102412