In Vitro Inhibition of Cryptosporidium parvum Infection by the Olive Oil Component Oleocanthal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Host Cell Culture

2.2. Inhibitors and Treatment Protocols

2.3. XTT Tests

2.4. C. parvum Oocyst Excystation and Host Cell Infection

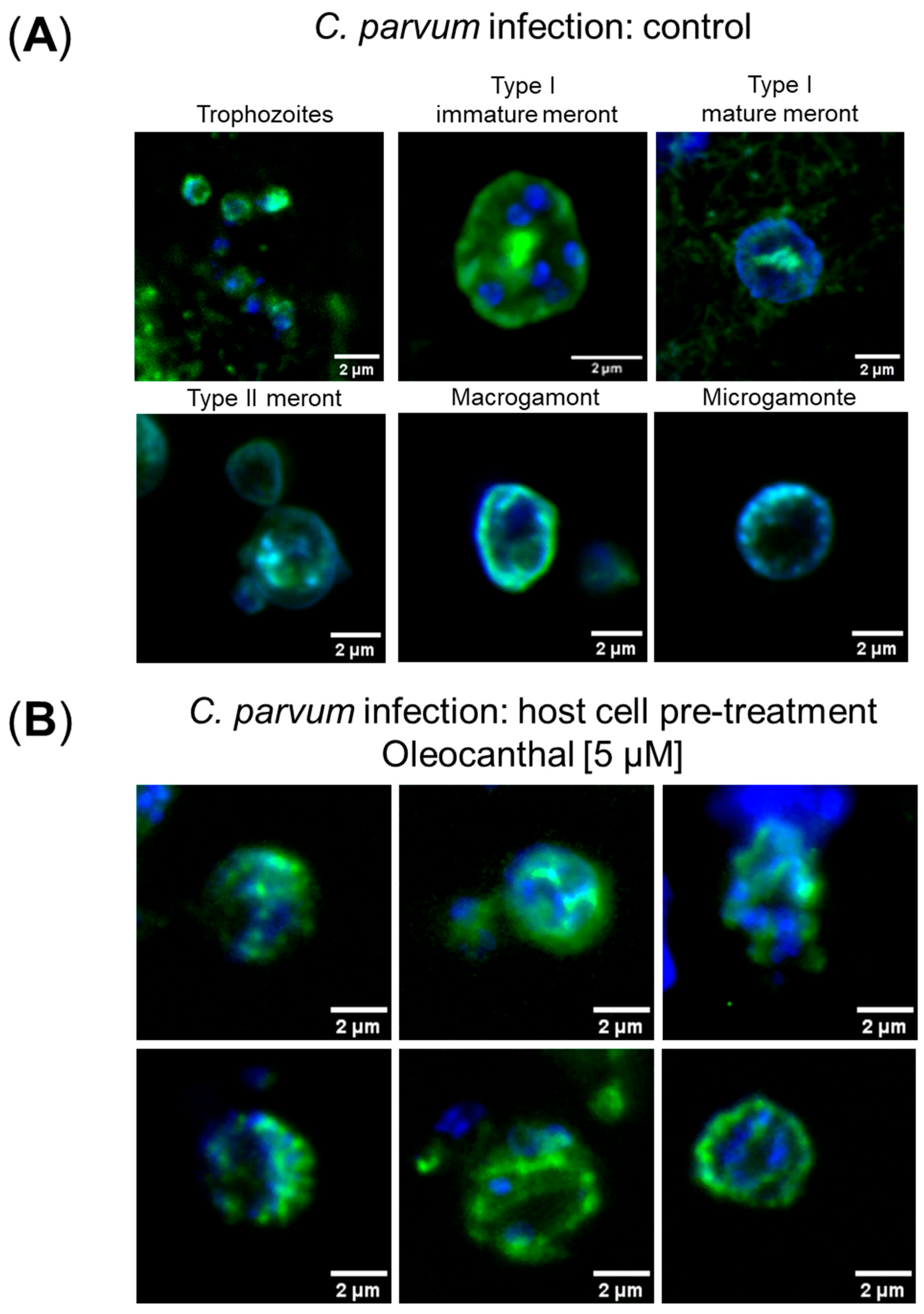

2.5. Immunofluorescence Microscopic Detection of Intracellular C. parvum Stages

2.6. Fluorescence Image Acquisition

2.7. Quantification of Metabolic Conversion Rates in Host Cell Culture Supernatants

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Oleocanthal and PP242 Treatments on C. parvum Infection

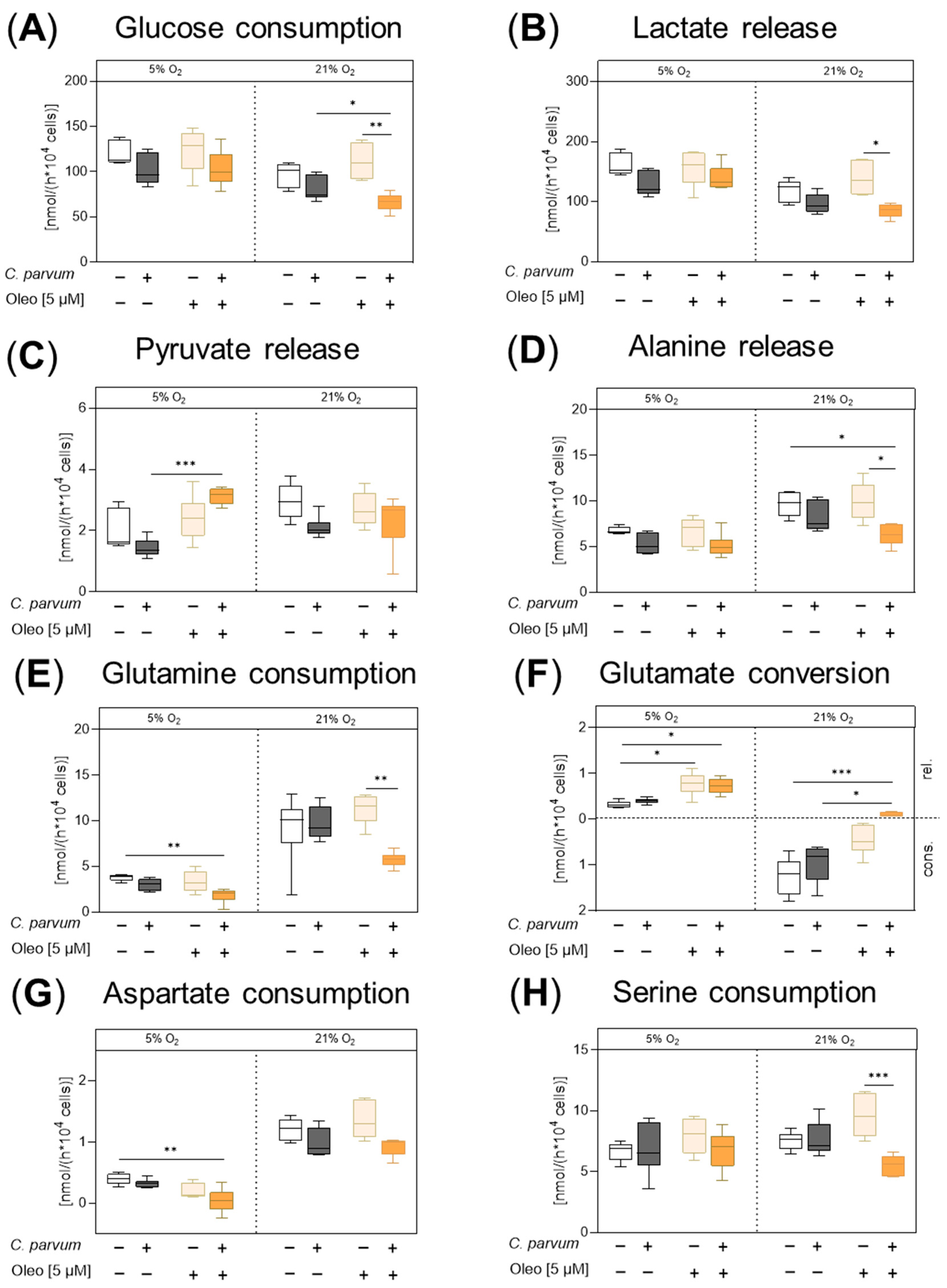

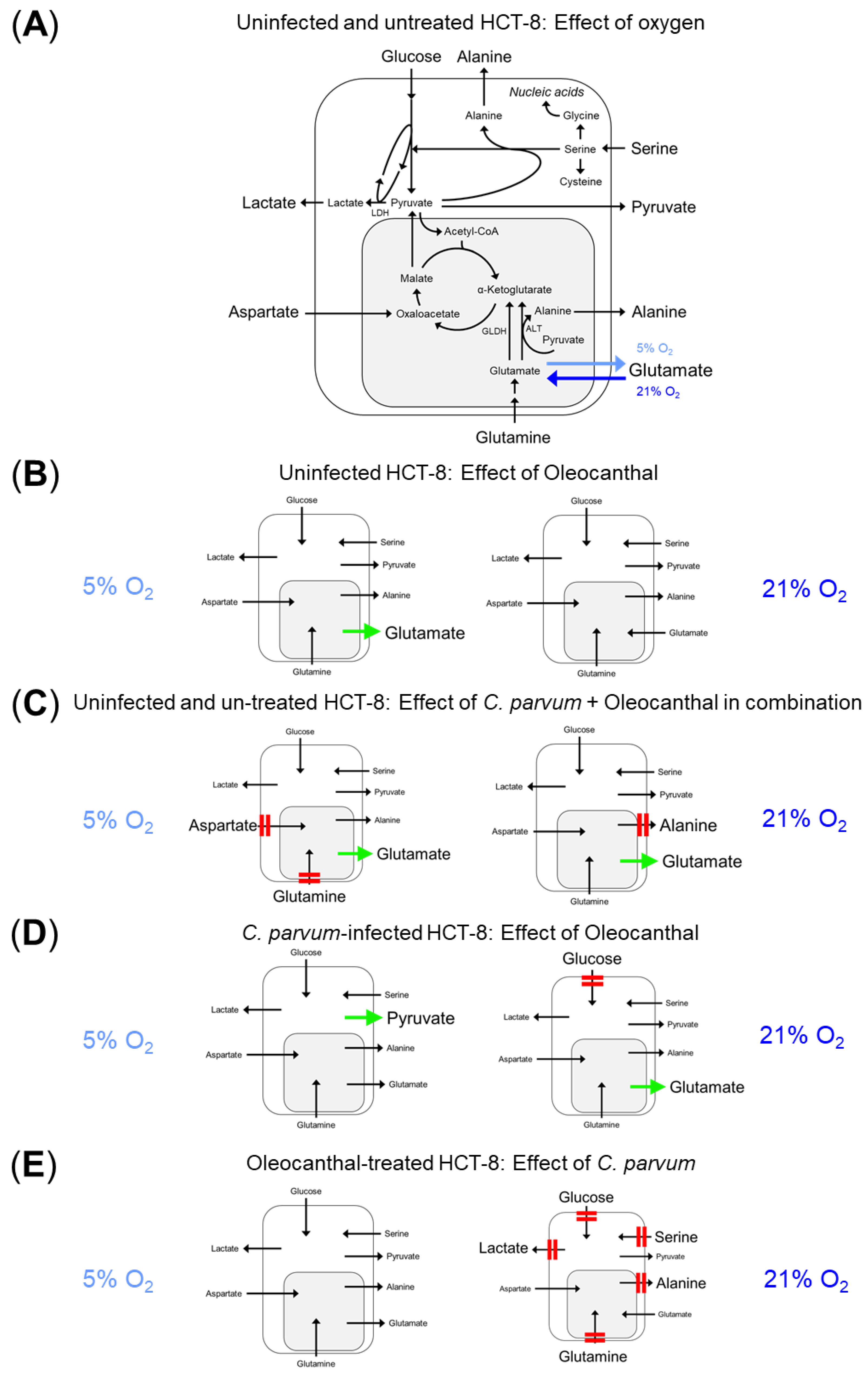

3.2. Impact of Oleocanthal Treatment on the Metabolic Signature of C. parvum-Infected HCT-8 Cells in Physioxia and Hyperoxia

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| HK | Hexokinase |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MCT | Monocarboxylate transporters |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| Oleo | Oleocanthal |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PP242 | 2-(4-Amino-1-isopropyl-1H-pyrazolo [3,4-d]pyrimidin-3-yl)-1H-indol-5-ol, Dihydrate |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

References

- Ryan, U.; Hijjawi, N.; Xiao, L. Foodborne cryptosporidiosis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.C.; Palmer, C.S.; O’Handley, R. The public health and clinical significance of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in domestic animals. Vet. J. 2008, 177, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Clinical Care of Crypto. Cryptosporidium (“Crypto”). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cryptosporidium/hcp/clinical-care/index.html (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Hasan, M.M.; Stebbins, E.E.; Choy, R.K.M.; Gillespie, J.R.; de Hostos, E.L.; Miller, P.; Mushtaq, A.; Ranade, R.M.; Teixeira, J.E.; Verlinde, C.; et al. Spontaneous Selection of Cryptosporidium Drug Resistance in a Calf Model of Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.A.; Clark, D.P. Cryptosporidium parvum Induces Host Cell Actin Accumulation at the Host-Parasite Interface. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 2315–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, S.D., Jr.; Zhu, G. Cryptosporidium: Genomic and biochemical features. Exp. Parasitol. 2010, 124, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Beatty, W.L.; Greigert, V.; Witola, W.H.; Sibley, L.D. Multiple pathways for glucose phosphate transport and utilization support growth of Cryptosporidium parvum. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengler, F.; Hammon, H.M.; Liermann, W.; Görs, S.; Bachmann, L.; Helm, C.; Ulrich, R.; Delling, C. Cryptosporidium parvum competes with the intestinal epithelial cells for glucose and impairs systemic glucose supply in neonatal calves. Vet. Res. 2023, 54, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhal, A.K.; Pani, A.; Mahapatra, R.K.; Yun, S.I. In-silico screening of small molecule inhibitors against Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) of Cryptosporidium parvum. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2018, 77, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ltahan, R.; Guo, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, G. The Action of the Hexokinase Inhibitor 2-deoxy-d-glucose on Cryptosporidium parvum and the Discovery of Activities against the Parasite Hexokinase from Marketed Drugs. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2019, 66, 460–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayamba, F.; Faya, M.; Pooe, O.J.; Kushwaha, B.; Kushwaha, N.D.; Obakachi, V.A.; Nyamori, V.O.; Karpoormath, R. Lactate dehydrogenase and malate dehydrogenase: Potential antiparasitic targets for drug development studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 50, 116458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, J.; Velasquez, Z.; Silva, L.M.R.; Gärtner, U.; Failing, K.; Daugschies, A.; Mazurek, S.; Hermosilla, C.; Taubert, A. Metabolic Signatures of Cryptosporidium parvum-Infected HCT-8 Cells and Impact of Selected Metabolic Inhibitors on C. parvum Infection under Physioxia and Hyperoxia. Biology 2021, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Roellig, D.M.; Guo, Y.; Li, N.; Frace, M.A.; Tang, K.; Zhang, L.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, L. Evolution of mitosome metabolism and invasion-related proteins in Cryptosporidium. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogi, T.; Kita, K. Diversity in mitochondrial metabolic pathways in parasitic protists Plasmodium and Cryptosporidium. Parasitol. Int. 2010, 59, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, V.; Wakeman, K.C.; Keeling, P.J. Parallel functional reduction in the mitochondria of apicomplexan parasites. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 2920–2928.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, J.; Silva, L.M.R.; Gärtner, U.; Daugschies, A.; Mazurek, S.; Hermosilla, C.; Taubert, A. First Metabolic Insights into Ex Vivo Cryptosporidium parvum-Infected Bovine Small Intestinal Explants Studied under Physioxic Conditions. Biology 2021, 10, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, R.V.; Oppliger, W.; Robitaille, A.M.; Heiserich, L.; Skendaj, R.; Gottlieb, E.; Hall, M.N. Glutaminolysis activates Rag-mTORC1 signaling. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, B.D.; Diering, G.H.; Bidinosti, M.A.; Dalal, K.; Alain, T.; Balgi, A.D.; Forestieri, R.; Nodwell, M.; Rajadurai, C.V.; Gunaratnam, C.; et al. Structure-Activity Analysis of Niclosamide Reveals Potential Role for Cytoplasmic pH in Control of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 (mTORC1) Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 17530–17545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Yao, F.; Su, Q.; Liu, D.; Xue, R.; Dai, G.; Fang, R.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. AMPK inhibits cardiac hypertrophy by promoting autophagy via mTORC1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 558, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Guan, K.L. mTOR as a central hub of nutrient signalling and cell growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wu, Y.; Yu, S.; Li, X.; Wang, A.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Lu, Y. Critical role of mTOR in regulating aerobic glycolysis in carcinogenesis (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2021, 58, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwed, A.; Kim, E.; Jacinto, E. Regulation and Metabolic Functions of mTORC1 and mTORC2. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 1371–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodineau, C.; Tome, M.; Courtois, S.; Costa, A.S.H.; Sciacovelli, M.; Rousseau, B.; Richard, E.; Vacher, P.; Parejo-Perez, C.; Bessede, E.; et al. Two parallel pathways connect glutamine metabolism and mTORC1 activity to regulate glutamoptosis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquette, M.; El-Houjeiri, L.; Pause, A. mTOR Pathways in Cancer and Autophagy. Cancers 2018, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Z.; Tao, T.; Li, H.; Zhu, X. mTOR signaling pathway and mTOR inhibitors in cancer: Progress and challenges. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.S.; Mitra, K.; Akter, S.; Ramproshad, S.; Mondal, B.; Khan, I.N.; Islam, M.T.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Calina, D.; Cho, W.C. Recent advances and limitations of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafie, S.K.; Al-Mulla, F.; Abubaker, J. mTOR: Its Critical Role in Metabolic Diseases, Cancer, and the Aging Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Cho, S.; Blenis, J. mTORC1, the maestro of cell metabolism and growth. Genes Dev. 2025, 39, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.M.; Lee, H.; Jung, B.H. Metabolite identification and pharmacokinetic profiling of PP242, an ATP-competitive inhibitor of mTOR using ultra high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2018, 1072, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes, M.R.; Limon, J.J.; So, L.; Chen, J.; Lim, R.J.; Chavez, M.A.; Vu, C.; Lilly, M.B.; Mallya, S.; Ong, S.T.; et al. Effective and selective targeting of Ph+ leukemia cells using a TORC1/2 kinase inhibitor. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanfar, M.A.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Akl, M.R.; El Sayed, K.A. Olive Oil-derived Oleocanthal as Potent Inhibitor of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin: Biological Evaluation and Molecular Modeling Studies. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1776–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Kelly, C.J.; Colgan, S.P. Physiologic hypoxia and oxygen homeostasis in the healthy intestine. A Review in the Theme: Cellular Responses to Hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2015, 309, C350–C360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandel, J.; English, E.D.; Sateriale, A.; Gullicksrud, J.A.; Beiting, D.P.; Sullivan, M.C.; Pinkston, B.; Striepen, B. Life cycle progression and sexual development of the apicomplexan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2226–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Paola, F.J.; Cardoso, L.H.; Nikitopoulou, E.; Kulik, B.; Rühl, S.; Eva, A.; Sommer, N.; Linn, T.; Gnaiger, E.; Failing, K.; et al. Impact of mtG3PDH inhibitors on proliferation and metabolism of androgen receptor-negative prostate cancer cells: Role of extracellular pyruvate. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0325509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haouari, M.; Quintero, J.E.; Rosado, J.A. Anticancer molecular mechanisms of oleocanthal. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2820–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannati, S.; Patel, A.; Patnaik, R.; Banerjee, Y. Oleocanthal as a Multifunctional Anti-Cancer Agent: Mechanistic Insights, Advanced Delivery Strategies, and Synergies for Precision Oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delafosse, A.; Chartier, C.; Dupuy, M.C.; Dumoulin, M.; Pors, I.; Paraud, C. Cryptosporidium parvum infection and associated risk factors in dairy calves in western France. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 118, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alba, P.; Garro, C.; Florin-Christensen, M.; Schnittger, L. Prevalence, risk factors and molecular epidemiology of neonatal cryptosporidiosis in calves: The Argentine perspective. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector. Borne. Dis. 2023, 4, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sone, B.; Ambe, L.A.; Ampama, M.N.; Ajohkoh, C.; Che, D.; Nguinkal, J.A.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C.; Kamena, F. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium Species in Diarrheic Children in Cameroon. Pathogens 2025, 14, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Shao, T.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. MiR-199a-3p regulates HCT-8 cell autophagy and apoptosis in response to Cryptosporidium parvum infection by targeting MTOR. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batarseh, Y.S.; Mohamed, L.A.; Al Rihani, S.B.; Mousa, Y.M.; Siddique, A.B.; El Sayed, K.A.; Kaddoumi, A. Oleocanthal Ameliorates Amyloid-beta Oligomers Toxicity on Astrocytes and Neuronal Cells: In-vitro Studies. Neuroscience 2017, 352, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhou, B.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lu, H.; Xia, M.; Guo, E.; Shan, W.; Chen, G.; Wang, C. Blockage of glutaminolysis enhances the sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to PI3K/mTOR inhibition involvement of STAT3 signaling. Tumour. Biol. 2016, 37, 11007–11015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Gong, P.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Li, J. Cryptosporidium parvum maintains intracellular survival by activating the host cellular EGFR-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 154, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Han, X.; Ou, D.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.; Jiang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J. Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mediated autophagy for tumor therapy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyamvada, S.; Jayawardena, D.; Bhalala, J.; Kumar, A.; Anbazhagan, A.N.; Alrefai, W.A.; Borthakur, A.; Dudeja, P.K. Cryptosporidium parvum infection induces autophagy in intestinal epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol. 2021, 23, e13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, G.K.; Keast, R.S.; Morel, D.; Lin, J.; Pika, J.; Han, Q.; Lee, C.H.; Smith, A.B.; Breslin, P.A. Phytochemistry: Ibuprofen-like activity in extra-virgin olive oil. Nature 2005, 437, 45–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B., 3rd; Han, Q.; Breslin, P.A.; Beauchamp, G.K. Synthesis and assignment of absolute configuration of (-)-oleocanthal: A potent, naturally occurring non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant agent derived from extra virgin olive oils. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5075–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez, M.; Ait Edjoudi, D.; Cordero-Barreal, A.; Farrag, M.; Varela-Garcia, M.; Torrijos-Pulpon, C.; Ruiz-Fernandez, C.; Capuozzo, M.; Ottaiano, A.; Lago, F.; et al. Oleocanthal, an Antioxidant Phenolic Compound in Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO): A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Its Potential in Inflammation and Cancer. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, M.; Mancini, C.; Lori, G.; Delre, P.; Ferraris, I.; Lucchini, F.; Molinario, A.; Leri, M.; Castellaneta, A.; Losito, I.; et al. Secoiridoid-enriched extra virgin olive oil extracts enhance mitochondrial activity and antioxidant response in colorectal cancer cells: The role of Oleacein and Oleocanthal in PPARγ interaction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 235, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaya, M.L.; Inguva, A.; Pei, S.; Jones, C.; Krug, A.; Ye, H.; Minhajuddin, M.; Winters, A.; Furtek, S.L.; Gamboni, F.; et al. The STAT3-MYC axis promotes survival of leukemia stem cells by regulating SLC1A5 and oxidative phosphorylation. Blood 2022, 139, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Liang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Liang, Z.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Niu, H. Glutamine affects T24 bladder cancer cell proliferation by activating STAT3 through ROS and glutaminolysis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 2189–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, T.; Meng, Q.; Han, J.; Sun, H.; Li, L.; Song, R.; Sun, B.; Pan, S.; Liang, D.; Liu, L. (-)-Oleocanthal inhibits growth and metastasis by blocking activation of STAT3 in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 43475–43491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, E.; El-Maadawy, A.; Bayomy, A.; Shakra, M.; Mohamed, A.; El shahat Mostafa, M.; Helal, H. Niclosamid modulates chronic Cryptosporidium-induced ileocecal adenocarcinoma in immunocompromised infected mice via targeting IL-6/IL-22-STAT3 axis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2025, 196, 105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsolaki, M.; Lazarou, E.; Kozori, M.; Petridou, N.; Tabakis, I.; Lazarou, I.; Karakota, M.; Saoulidis, I.; Melliou, E.; Magiatis, P. A Randomized Clinical Trial of Greek High Phenolic Early Harvest Extra Virgin Olive Oil in Mild Cognitive Impairment: The MICOIL Pilot Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 78, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Xiang, W.; He, Q.; Xiao, W.; Wei, H.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, M.; Yuan, X.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dietary polyphenols in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 47 randomized controlled trials. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1024120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, E.; Sharma, S.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Panzera, T.; Esposito, S.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; et al. Olive oil consumption and risk of breast cancer: Prospective results from the Moli-sani Study, and a systematic review of observational studies and randomized clinical trials. Eur. J. Cancer 2025, 224, 115520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, A.B.; King, J.A.; Meyer, S.A.; Abdelwahed, K.; Busnena, B.; El Sayed, K. Safety Evaluations of Single Dose of the Olive Secoiridoid S-(-)-Oleocanthal in Swiss Albino Mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Yerena, A.; Vallverdu-Queralt, A.; Mols, R.; Augustijns, P.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Escribano-Ferrer, E. Absorption and Intestinal Metabolic Profile of Oleocanthal in Rats. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikou, T.; Sakavitsi, M.E.; Kalampokis, E.; Halabalaki, M. Metabolism and Bioavailability of Olive Bioactive Constituents Based on In Vitro, In Vivo and Human Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajmim, A.; Cuevas-Ocampo, A.K.; Siddique, A.B.; Qusa, M.H.; King, J.A.; Abdelwahed, K.S.; Sonju, J.J.; El Sayed, K.A. (-)-Oleocanthal Nutraceuticals for Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid Pathology: Novel Oral Formulations, Therapeutic, and Molecular Insights in 5xFAD Transgenic Mice Model. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ampama, M.N.; Hanke, D.; Velásquez, Z.D.; Wäber, N.B.; Hermosilla, C.; Taubert, A.; Mazurek, S. In Vitro Inhibition of Cryptosporidium parvum Infection by the Olive Oil Component Oleocanthal. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101002

Ampama MN, Hanke D, Velásquez ZD, Wäber NB, Hermosilla C, Taubert A, Mazurek S. In Vitro Inhibition of Cryptosporidium parvum Infection by the Olive Oil Component Oleocanthal. Pathogens. 2025; 14(10):1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101002

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmpama, M. Nguele, Dominik Hanke, Zahady D. Velásquez, Nadine B. Wäber, Carlos Hermosilla, Anja Taubert, and Sybille Mazurek. 2025. "In Vitro Inhibition of Cryptosporidium parvum Infection by the Olive Oil Component Oleocanthal" Pathogens 14, no. 10: 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101002

APA StyleAmpama, M. N., Hanke, D., Velásquez, Z. D., Wäber, N. B., Hermosilla, C., Taubert, A., & Mazurek, S. (2025). In Vitro Inhibition of Cryptosporidium parvum Infection by the Olive Oil Component Oleocanthal. Pathogens, 14(10), 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens14101002