Investigation on the Impact Resistance of Bridge Piers with a Reinforced Concrete Composite Structure Against Debris Flow

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Simulated Model Tests

2.1. Model Box

2.2. Simulate Debris Flows

2.3. Round-Ended Bridge Pier Model

2.4. Reinforced Concrete (RC) Composite Protective Structure Model

3. Results and Discussion

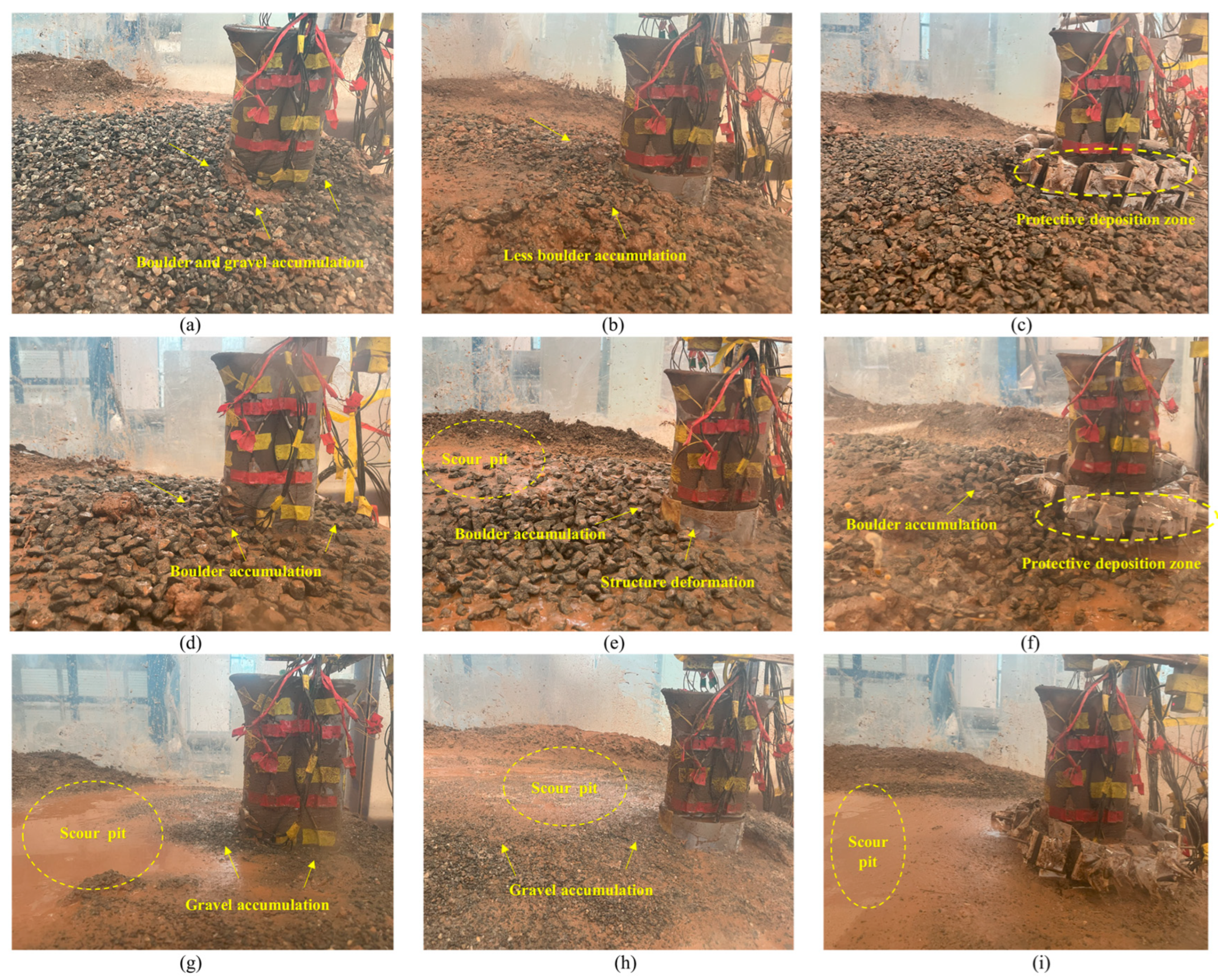

3.1. Macroscopic Damage

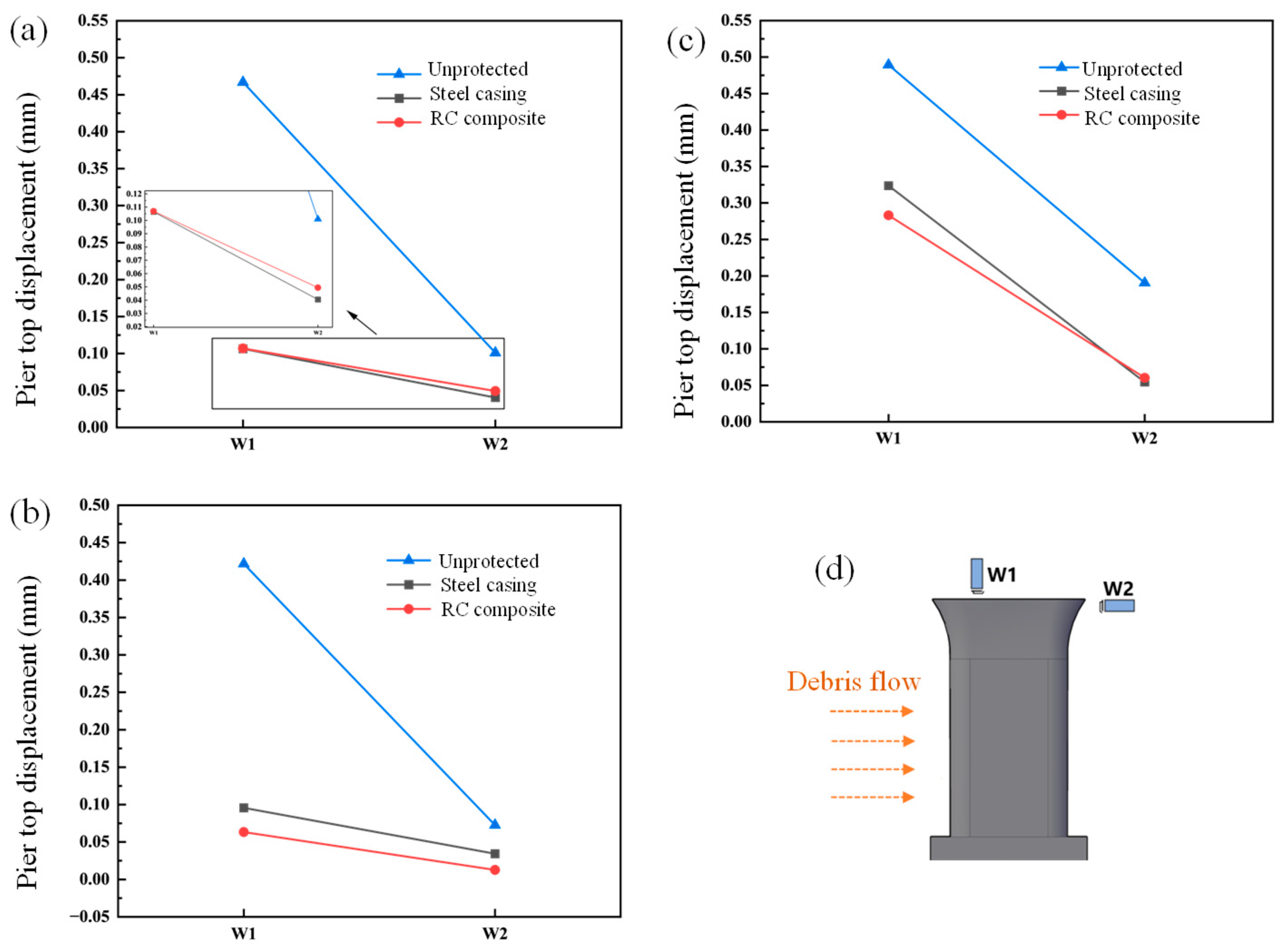

3.2. Pier Top Displacement

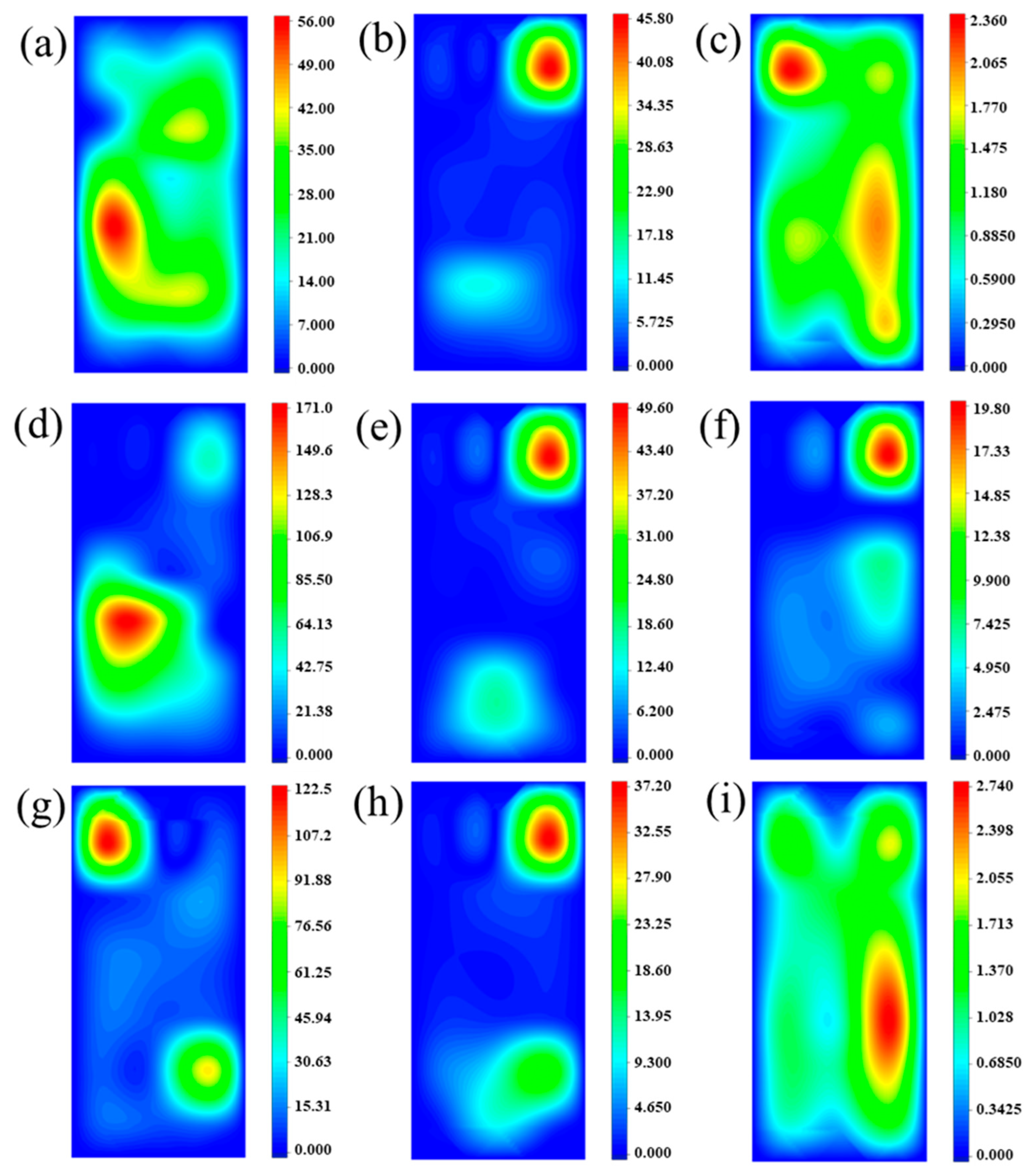

3.3. Bending Moment

3.4. Dynamic Pressure Distribution

3.4.1. Peak Impact Pressure

3.4.2. Pressure Distribution

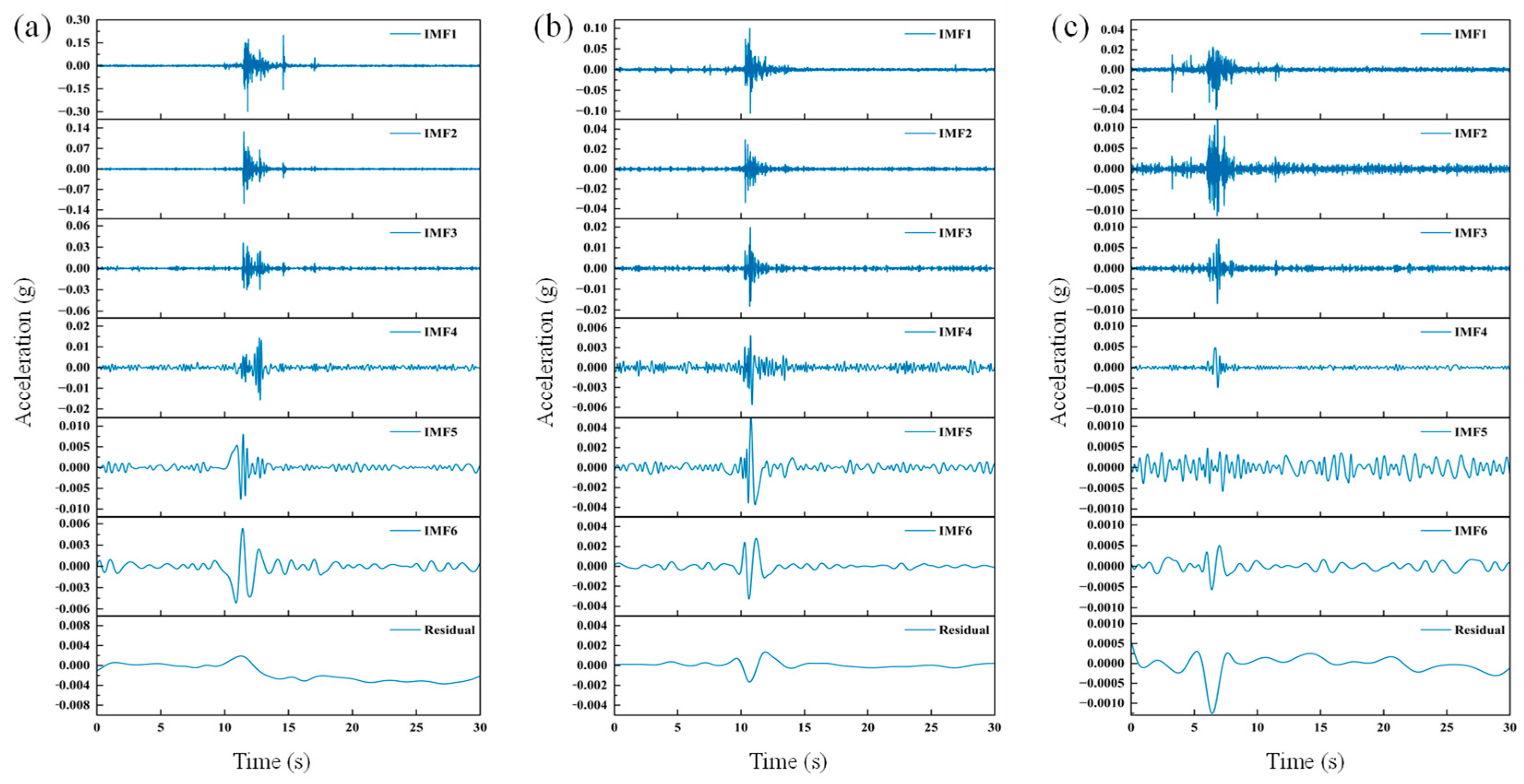

3.5. Energy Distribution

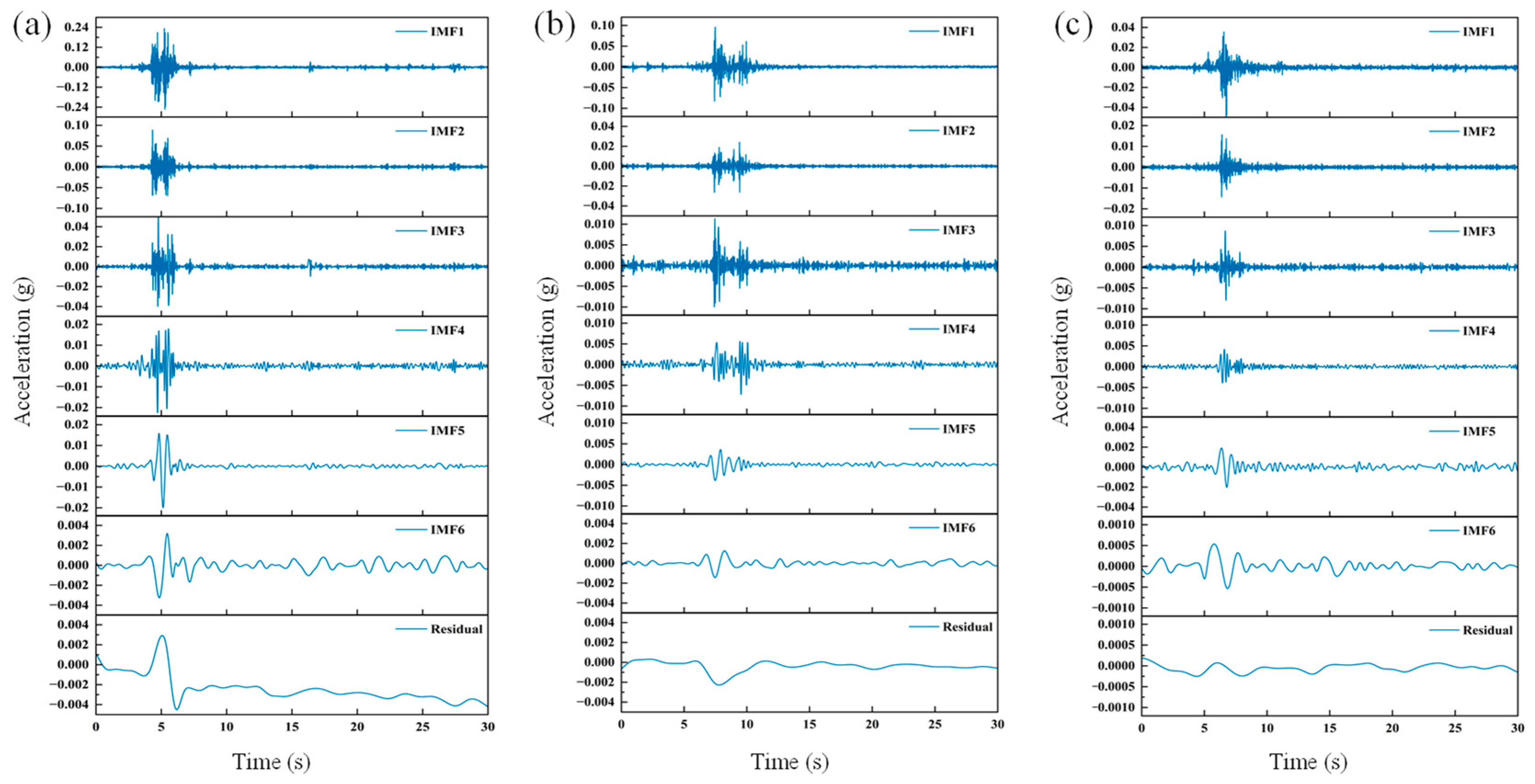

3.5.1. Instantaneous Frequency Spectra

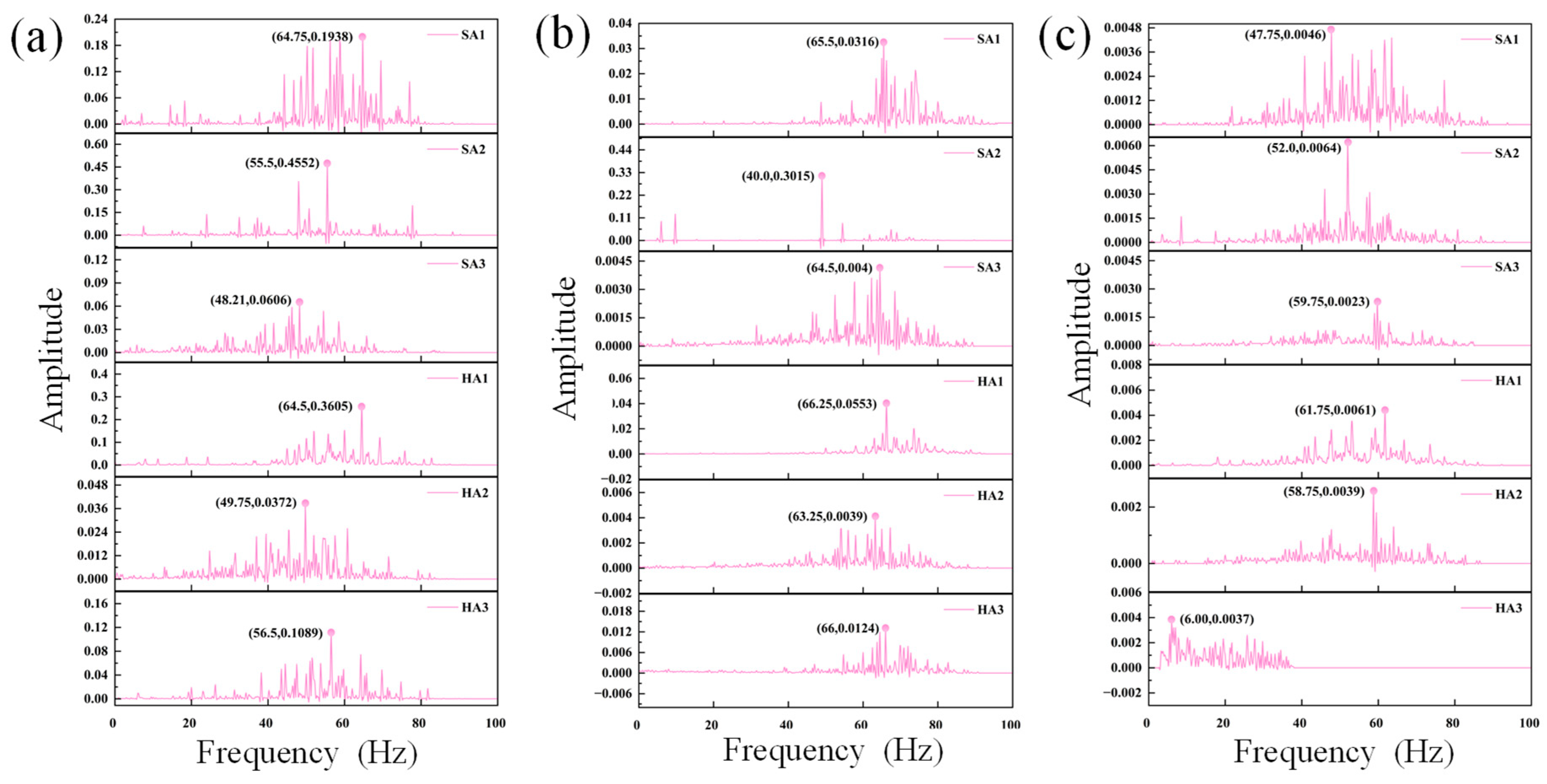

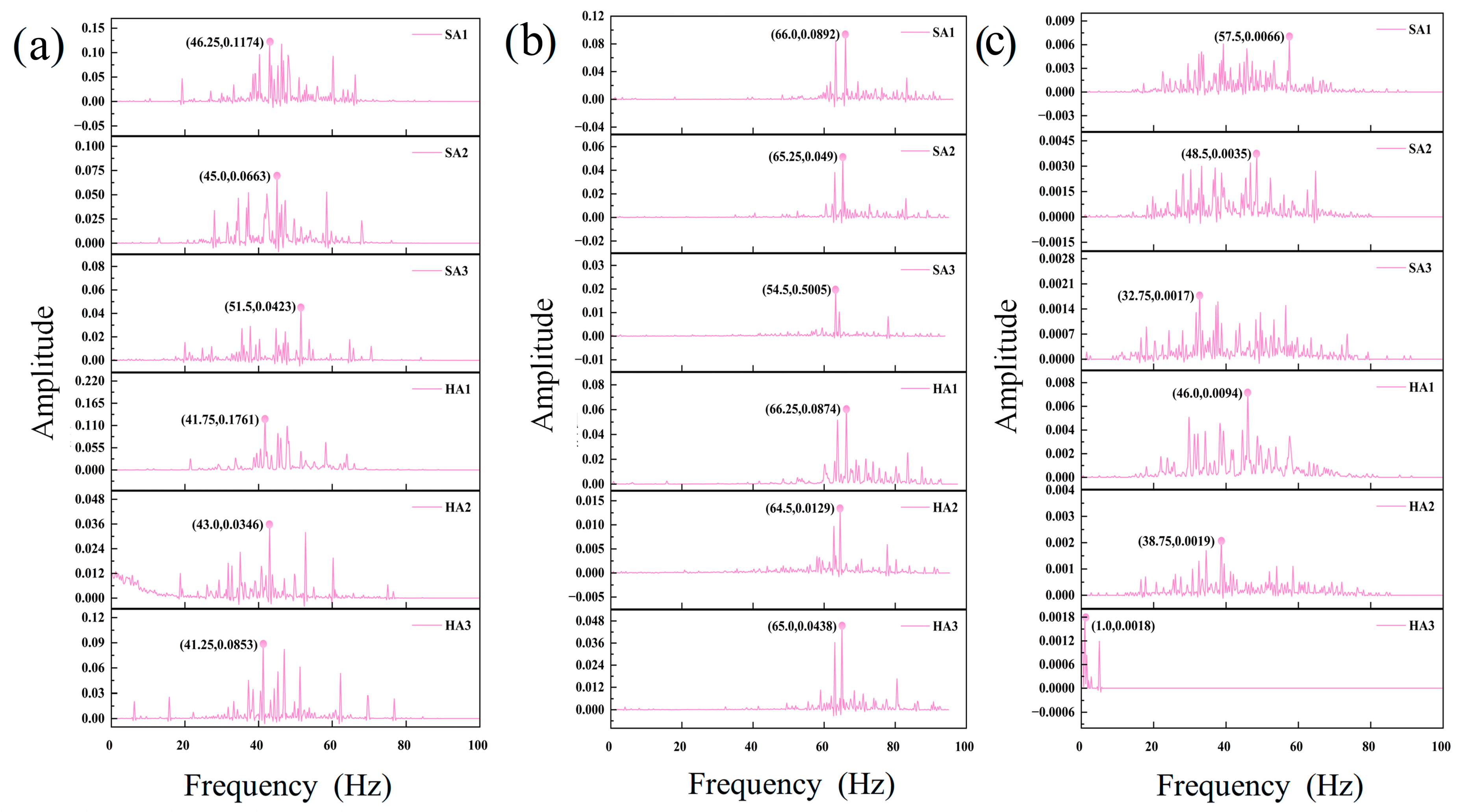

3.5.2. Marginal Spectrum Analysis

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- All types of debris flows lead to an accumulation of gravel and the formation of scouring pits on the upstream surfaces of round-ended piers. The steel casing mitigated some of direct impacts from debris flows, reducing the accumulation of large rocks and gravel and smaller sized scouring pits. In contrast, the RC composite structure exhibited more pronounced effects and effectively deflected large rocks, promoting their deposition away from the pier. The incorporated buffer layers established a protective deposition zone on the upstream surface of the pier, significantly reducing the sizes of scouring pits.

- (2)

- The RC composite structure significantly reduced the pier top displacement and pier body bending moments and optimized pressure distribution on the pier body. Compared with the unprotected round-ended bridge pier, the steel casting decreased the lateral pier top displacements by 51.2%, 75.3%, and 52.1% and vertical displacements by 76.6%, 31.2%, and 76.2% in DF1, DF2, and DF3, respectively. The RC composite structure decreased the lateral displacement by 75.5%, 77.4%, and 78.9% and vertical displacement by 74.2%, 43.8%, and 86.9% in DF1, DF2, and DF3, respectively. Moreover, the steel casting reduced the bending moment on M1 and M3, respectively, by 76.2% and 78.55% in DF2, with reductions of 85.7% and 86.3% in the RC composite structure. The steel casting reduced peak pressure by 18.2%, 70.9%, and 69.7% under DF1, DF2, and DF3, respectively. These reductions increased to 95.7%, 88.4%, and 97.7% when using the RC composite structure.

- (3)

- The RC composite structure effectively absorbed impact-induced vibrations and weakened shock effects on the upstream face, exhibiting superior capabilities compared with steel casing. Specifically, the RC composite protection optimized the marginal spectrum in DF3, demonstrating greater effectiveness in mitigating impact wave propagation and suppressing high-frequency responses compared with steel casing, showing particularly outstanding performance in gravel-dominated debris flows.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedl, C.; Scheidl, C.; Wernhart, S.; Proske, D. Assessing Granular Debris-Flow Impact Forces on Bridge Superstructures. J. Bridge Eng. 2024, 29, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.R.; Xu, C.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Q.C.; Qiang, B. Study on the Destruction Process of Piers by Debris Flow Impact Using SPH-FEM Adaptive Coupling Method. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 3162–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, T.; Martini, M.; Bettella, F.; D’Agostino, V. Debris flow and debris flood hazard assessment in mountain catchments. Catena 2024, 245, 108338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.B.; Liu, X.F.; Yao, C.R.; Li, Y.D. Debris-Flow Impact on Piers with Different Cross-Sectional Shapes. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.Z.; Wang, Z.L. Numerical Simulation of Debris Flow Impact on Pier With Different Cross-Sectional Shapes Based on Coupled CFD-DEM. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Met. 2025, 49, 2025–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coussot, P.; Laigle, D.; Arattano, M.; Deganutti, A.; Marchi, L. Direct Determination of Rheological Characteristics of Debris Flow. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1998, 124, 865–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iverson, R.M.; Logan, M.; LaHusen, R.G.; Berti, M. The perfect debris flow? Aggregated results from 28 large-scale experiments. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2010, 115, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, P.; Zeng, C.; Lei, Y. Experimental analysis on the impact force of viscous debris flow. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2015, 40, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Wei, F.; Wu, Y.; Qu, K.; Luo, X.; Ren, X.Y. Simulations of debris flow impacting on bridge pier based on coupled CFD-DEM method. Ocean Eng. 2023, 279, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.P.; Chen, Z.; He, S.M.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H. Measuring and estimating the impact pressure of debris flows on bridge piers based on large-scale laboratory experiments. Landslides 2018, 15, 1331–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, E.; Cunningham, L.S.; Rogers, B.D. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Floating Large Woody Debris Impact on a Masonry Arch Bridge. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xia, C.Y.; Wang, K.P.; Jiang, J.H.; Xia, H. Reliability-based vulnerability analysis of bridge pier subjected to debris flow impact. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2024, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.Q.; Yu, Z.X.; Zhang, C.; Lyu, L.; Zhao, L. Dynamic mechanical responses of reinforced concrete pier to debris avalanche impact based on the DEM-FEM coupled method. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2022, 167, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, C.; Scheidl, C.; Wernhart, S.; Proske, D. Laboratory experiments to analyse the influence of bridge profiles on debris-flow impact forces. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 415, 02006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.X.; He, S.M.; Wang, D.P.; Wu, Y. Design and optimisation of a protective device for bridge piers against debris flow impact. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2020, 79, 3321–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brighenti, R.; Segalini, A.; Ferrero, A.M. Debris flow hazard mitigation: A simplified analytical model for the design of flexible barriers. Comput. Geotech. 2013, 54, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.H.; Zhou, H.Y.; Peng, H.H.; Ye, J.H.; Bu, Z.Y. Experimental Study on Improving the Strength and Ductility of Prefabricated Concrete Bridge Piers Using GFRP Tube Confinement. Buildings 2025, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.L. Numerical Analysis of the Dynamic Response of Concrete Bridge Piers under the Impact of Rock Debris Flow. Buildings 2024, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowski, M. Numerical Simulation of Open Channel Flow between Bridge Piers. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2011, 15, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khafaji, M.S.; Abdulameer, L.; Al-Awadi, A.T.; Al Maimuri, N.M.L.; Al-Dujaili, A.N. Investigating the scour at piers of successive bridges with debris accumulation. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2025, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; He, S.M. Simulation of two-phase debris flow scouring bridge pier. J. Mt. Sci. 2017, 14, 2168–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cheng, B.; Xiao, H.; Li, W.; Huan, S. Dynamic mechanical performance of geogrid–waste tyre reinforced railway ballast under cyclic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Zhou, Y. Crashworthiness of composite sandwich structures with tailored Poisson’s ratios under bird strike. Int. J. Nonlin. Mech. 2026, 181, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ren, L.; Feng, K.; Wu, H.; Li, J.; Shao, J. Investigation of the dynamic response of h-type anti-slide pile based on shaking table test. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 182, 108736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DFD ρ/(kg/m3) | UWS γH/(kN/m3) | RC 1/n | SCC φ | ADD Hc/(m) | HG Ic/(m) | MBD dmax/(m) | MGD dmin/(m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.03 | 2.51 | 5.8 | 0.87 | 10 | 294 | 1.3 | 0.03–0.1 |

| Physical Quantity | Similarity Relation | Scale Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry (L) | SL | 1:40 |

| Elastic modulus (E) | SE | 1:1 |

| Stress (σ) | Sσ | 1:1 |

| Section modulus (W) | SW = SL3 | 1:64,000 |

| Moment of inertia (I) | SI = SL4 | 1:2,560,000 |

| Mid-span deflection (f) | Sf = SL | 1:40 |

| Impact force (P) | SP = SL2 | 1:1600 |

| Density (kg/m3) | Rock Particle Size (mm) | Mass Ratios (Rock–Sand–Water) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large | Medium | Small | |||

| Prototype | 1703 | 600–1300 | 200–600 | 80–200 | 5:4:1 |

| Similarity constant | 1:1 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:40 | 1:1 |

| DF1 | 1703 | 15–32.5 | 5–15 | 2–5 | 5:4:1 |

| DF2 | 1703 | 15–32.5 | - | - | 5:4:1 |

| DF3 | 1703 | - | - | 2–5 | 5:4:1 |

| Group | Mixed Rock (2–5:15:32.5 mm) (3:6:1) | Large Rock (15–32.5 mm) | Small Rock (2–5 mm) | Sand | Clay | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DF1 | 50.71 | - | - | 40.57 | 10.14 | 68.87 |

| DF2 | - | 50.71 | - | 40.57 | 10.14 | 68.87 |

| DF3 | - | - | 50.71 | 40.57 | 10.14 | 68.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, B. Investigation on the Impact Resistance of Bridge Piers with a Reinforced Concrete Composite Structure Against Debris Flow. Buildings 2025, 15, 4351. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234351

Wang Y, Li Y, Wu H, Li Y, Li J, Zhu B. Investigation on the Impact Resistance of Bridge Piers with a Reinforced Concrete Composite Structure Against Debris Flow. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4351. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234351

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yinsheng, Yongqiang Li, Honggang Wu, Yongchao Li, Jing Li, and Baolong Zhu. 2025. "Investigation on the Impact Resistance of Bridge Piers with a Reinforced Concrete Composite Structure Against Debris Flow" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4351. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234351

APA StyleWang, Y., Li, Y., Wu, H., Li, Y., Li, J., & Zhu, B. (2025). Investigation on the Impact Resistance of Bridge Piers with a Reinforced Concrete Composite Structure Against Debris Flow. Buildings, 15(23), 4351. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234351