Strengthening Width on Local Damage to Circular Piers Caused by Rolling Boulder Impacts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Influence of Outsourced Carbon Fiber Cloth Width on Strengthening

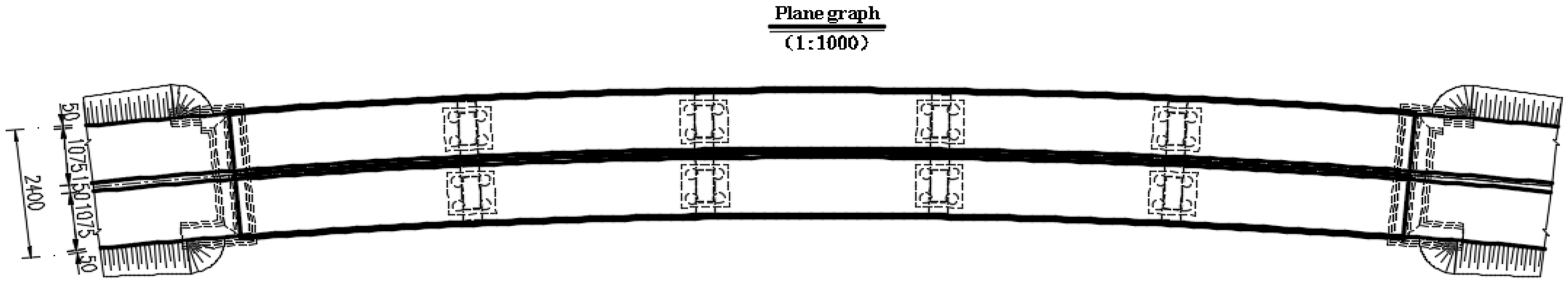

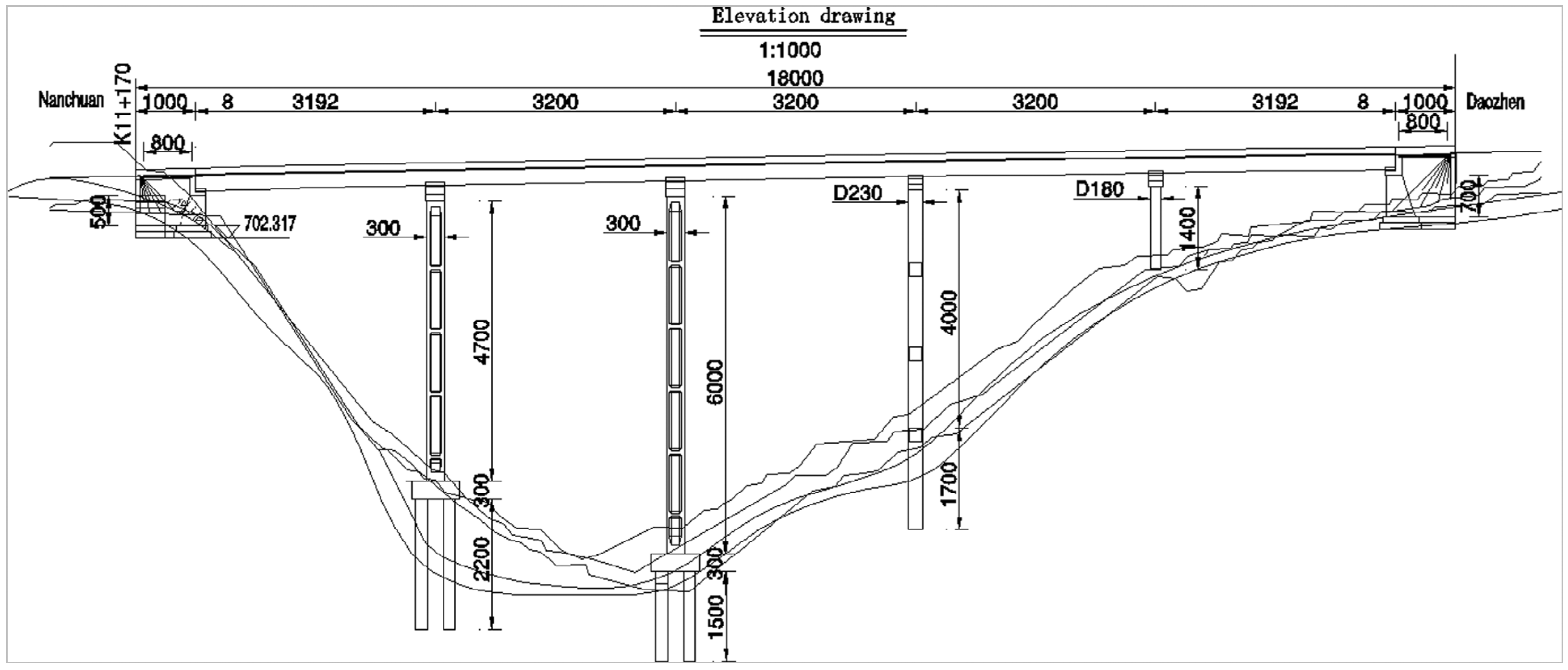

2.1. Engineering Background

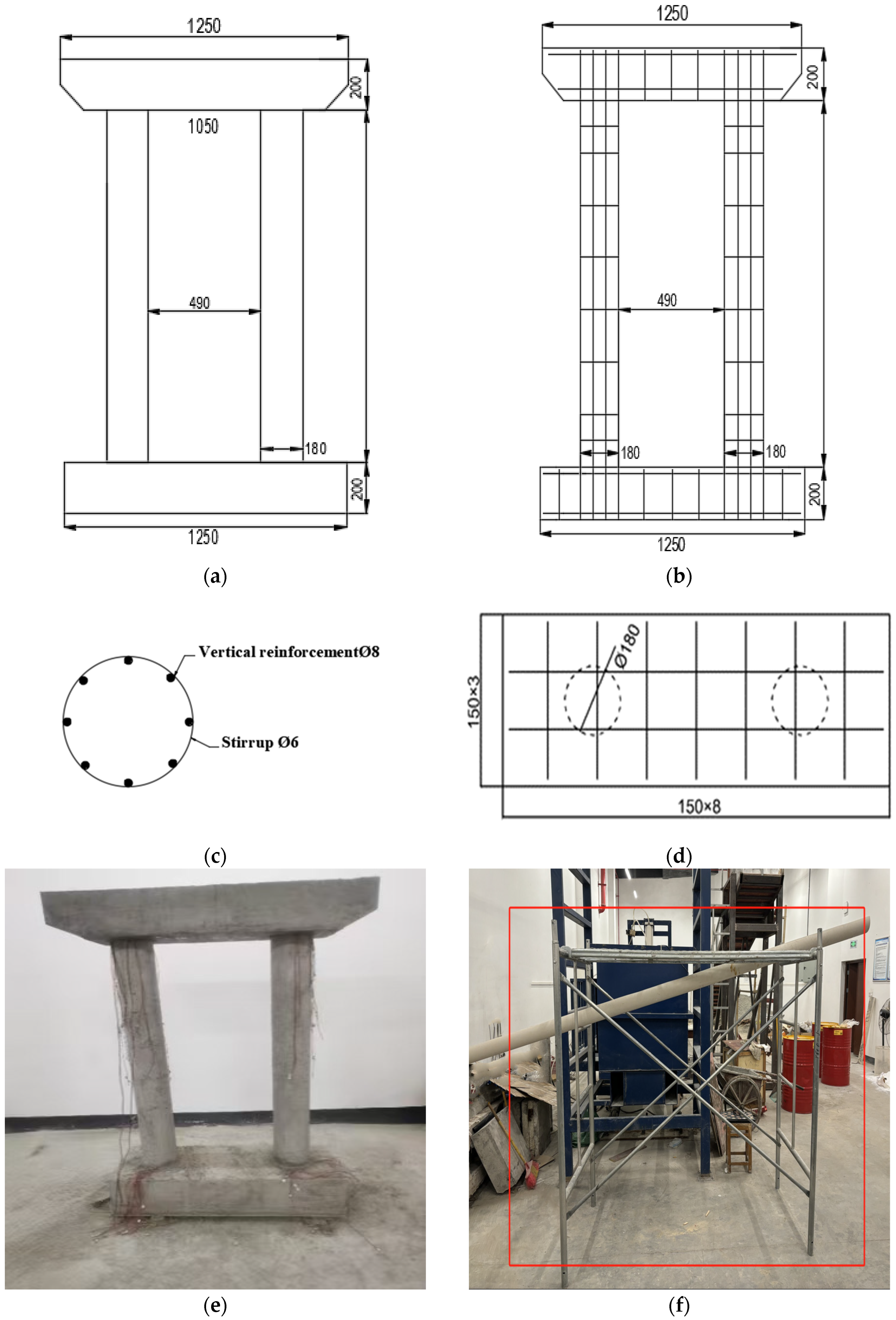

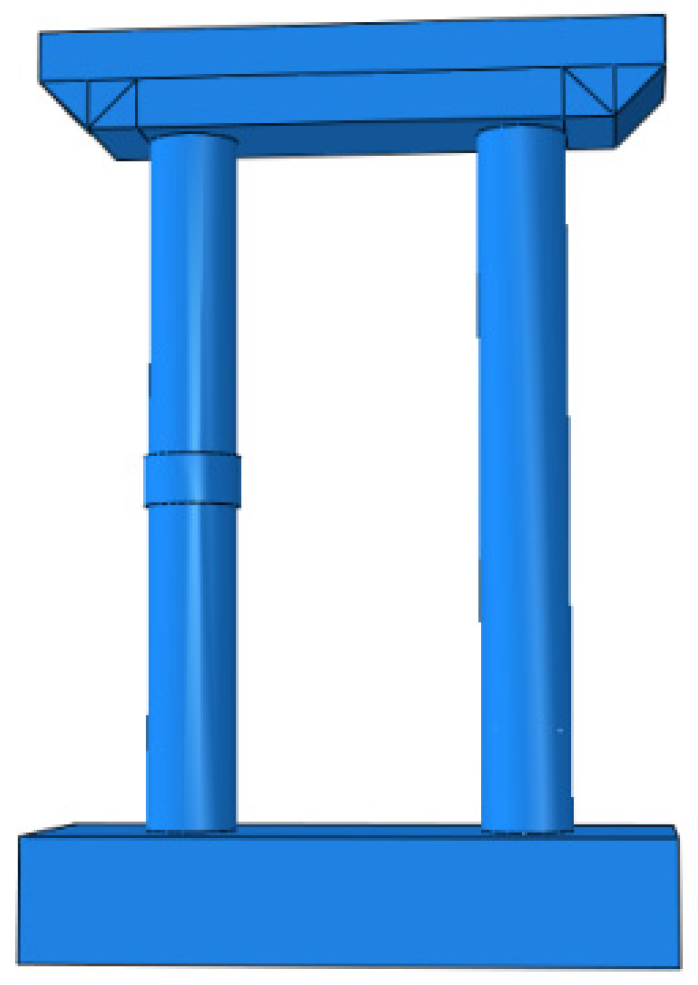

2.2. Experimental Model Analysis

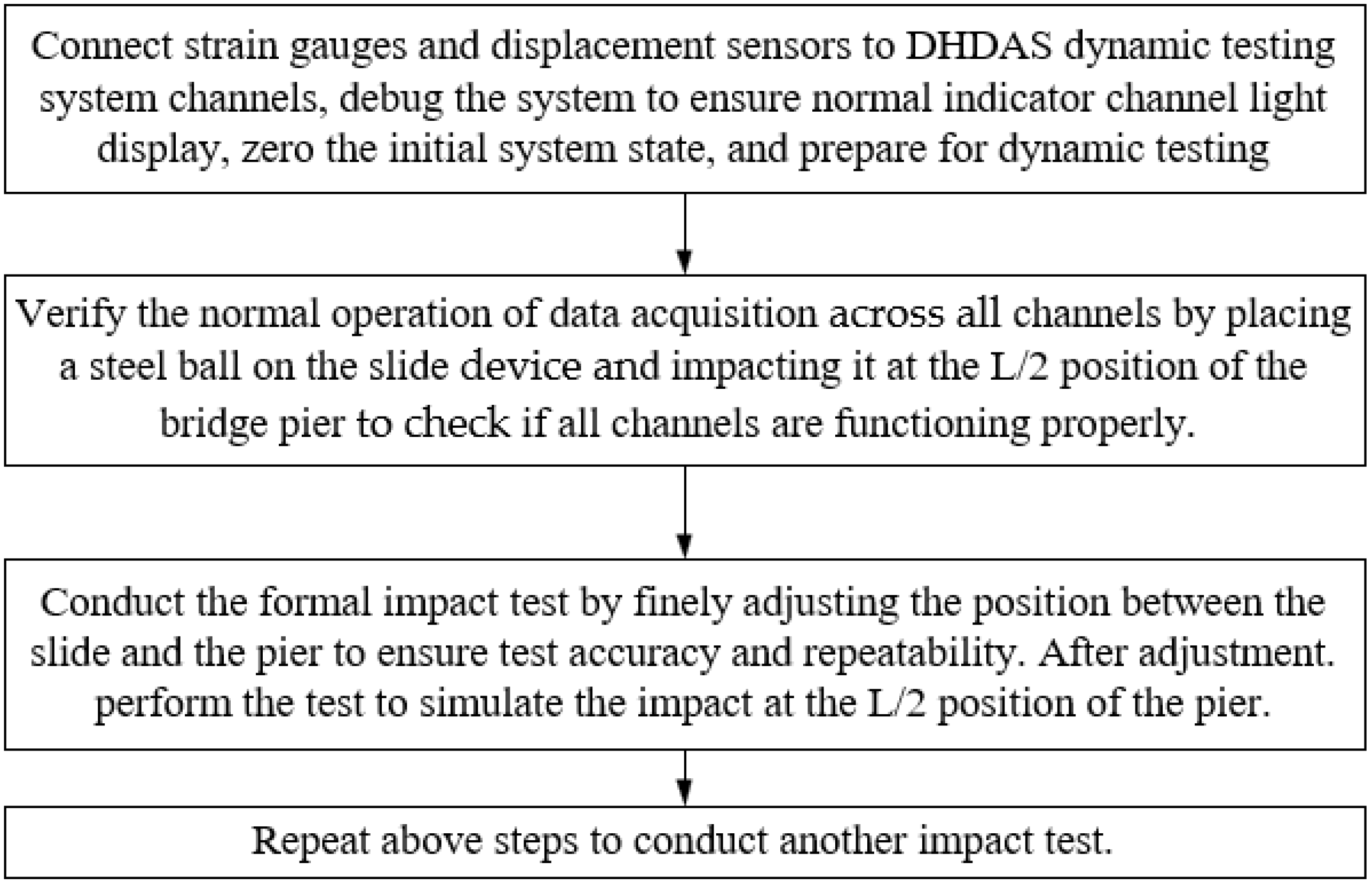

2.2.1. Bridge Pier Strengthening Impact Test

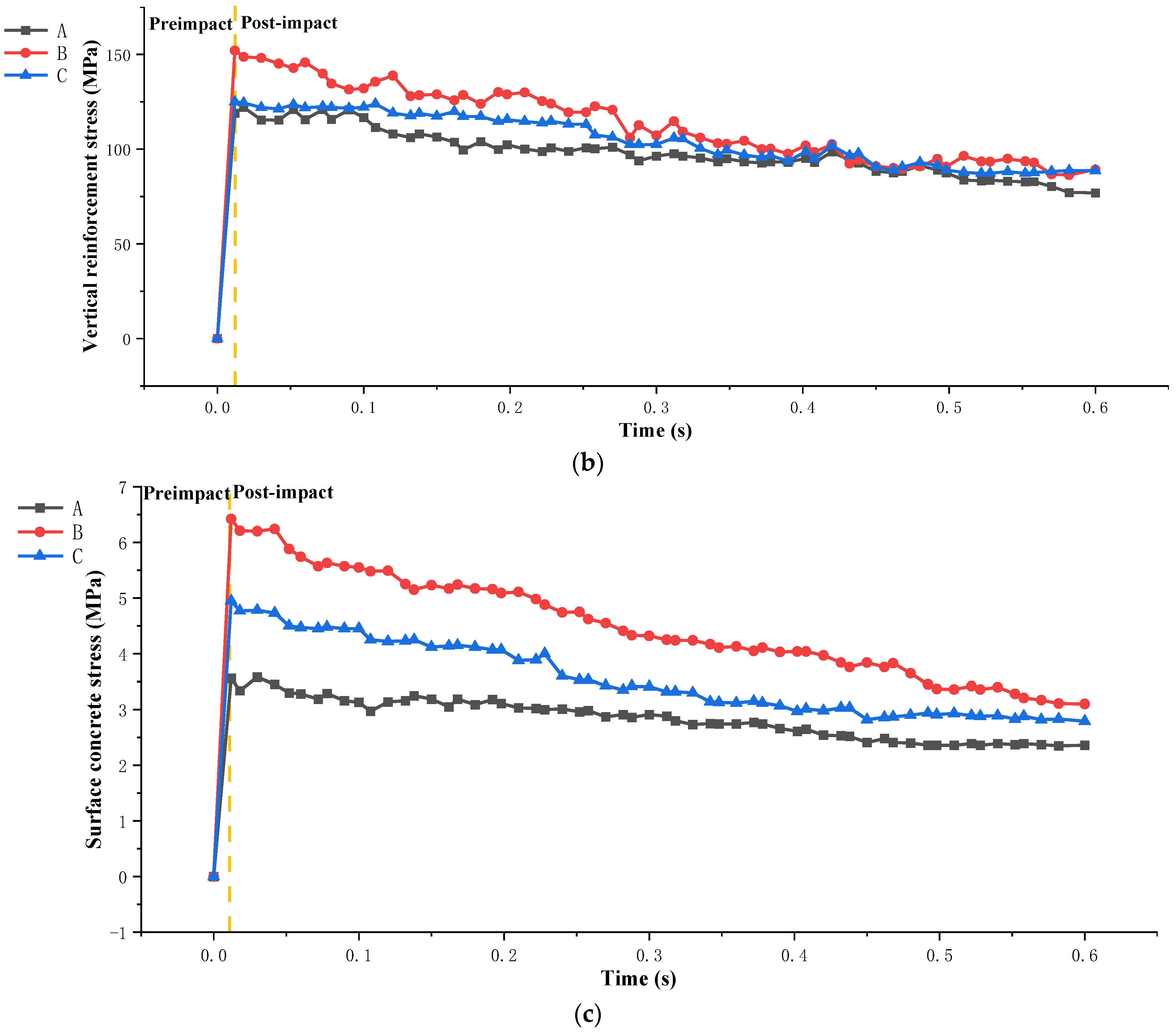

2.2.2. Analysis of Test Results

2.2.3. Comparative Analysis of Strengthening Test Results and Simulation Results

2.3. Finite Element Simulation of Outsourced Carbon Fiber Cloth

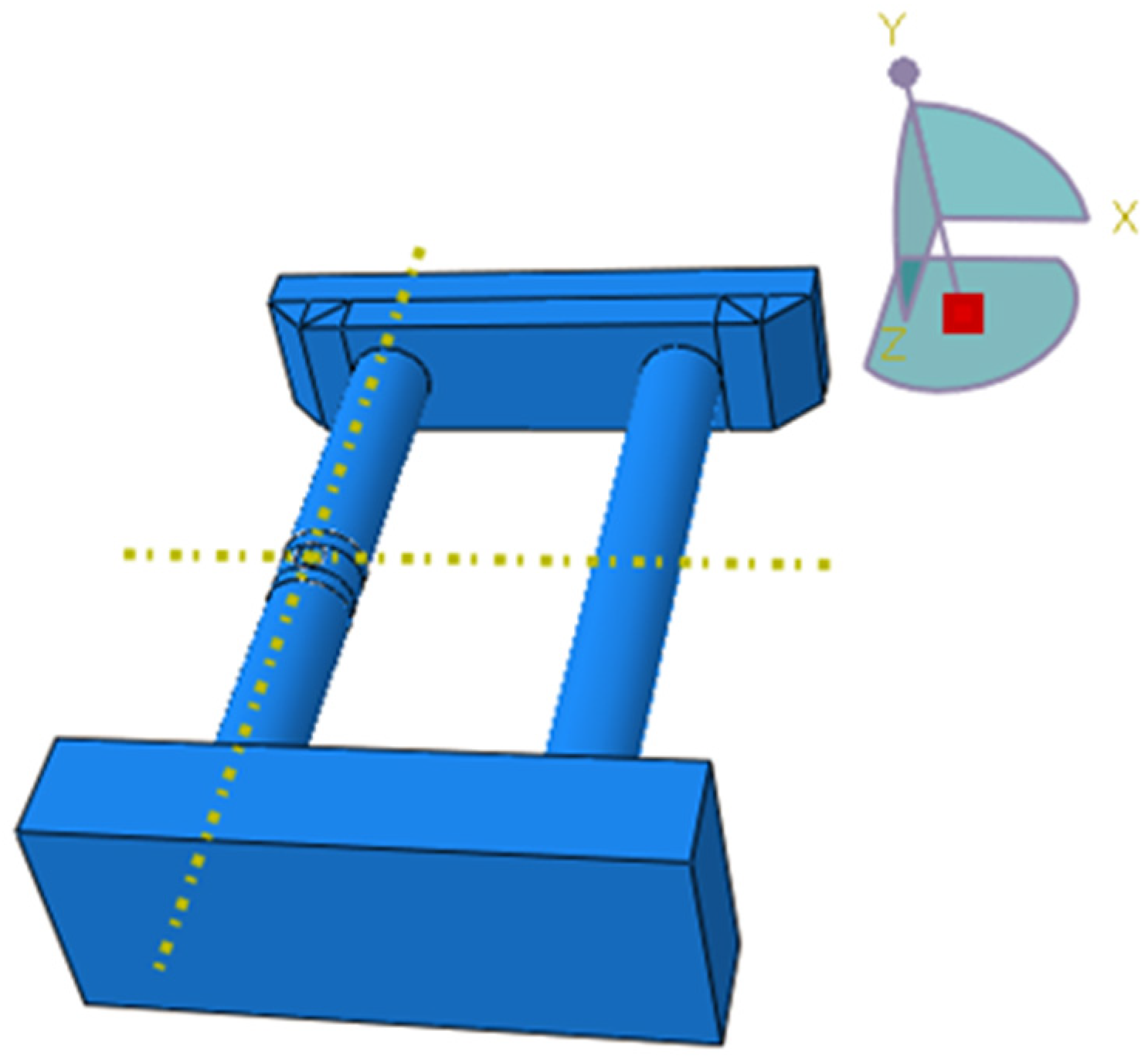

2.3.1. Establishment of Finite Element Simulation for Outsourced Carbon Fiber Cloth Strengthening

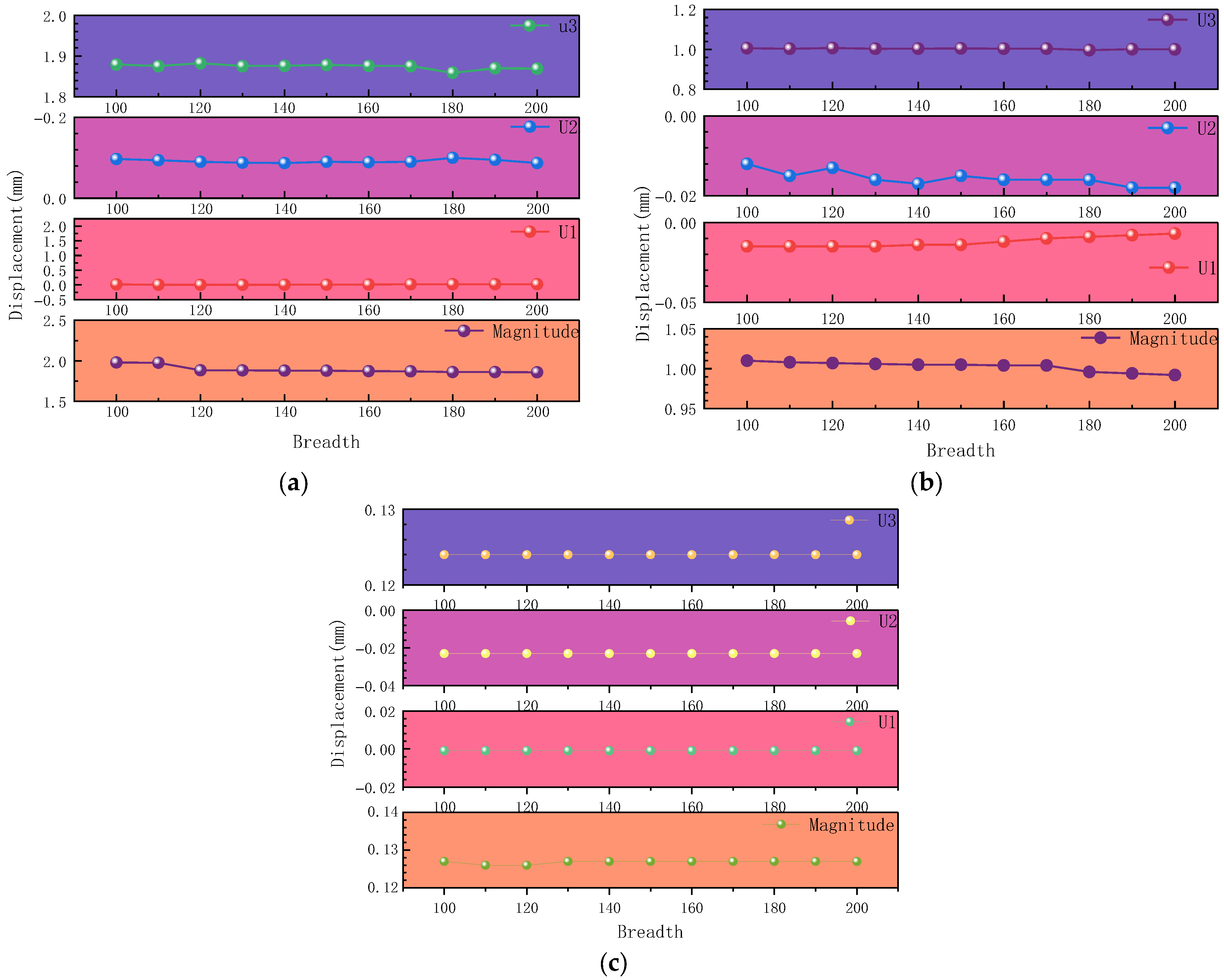

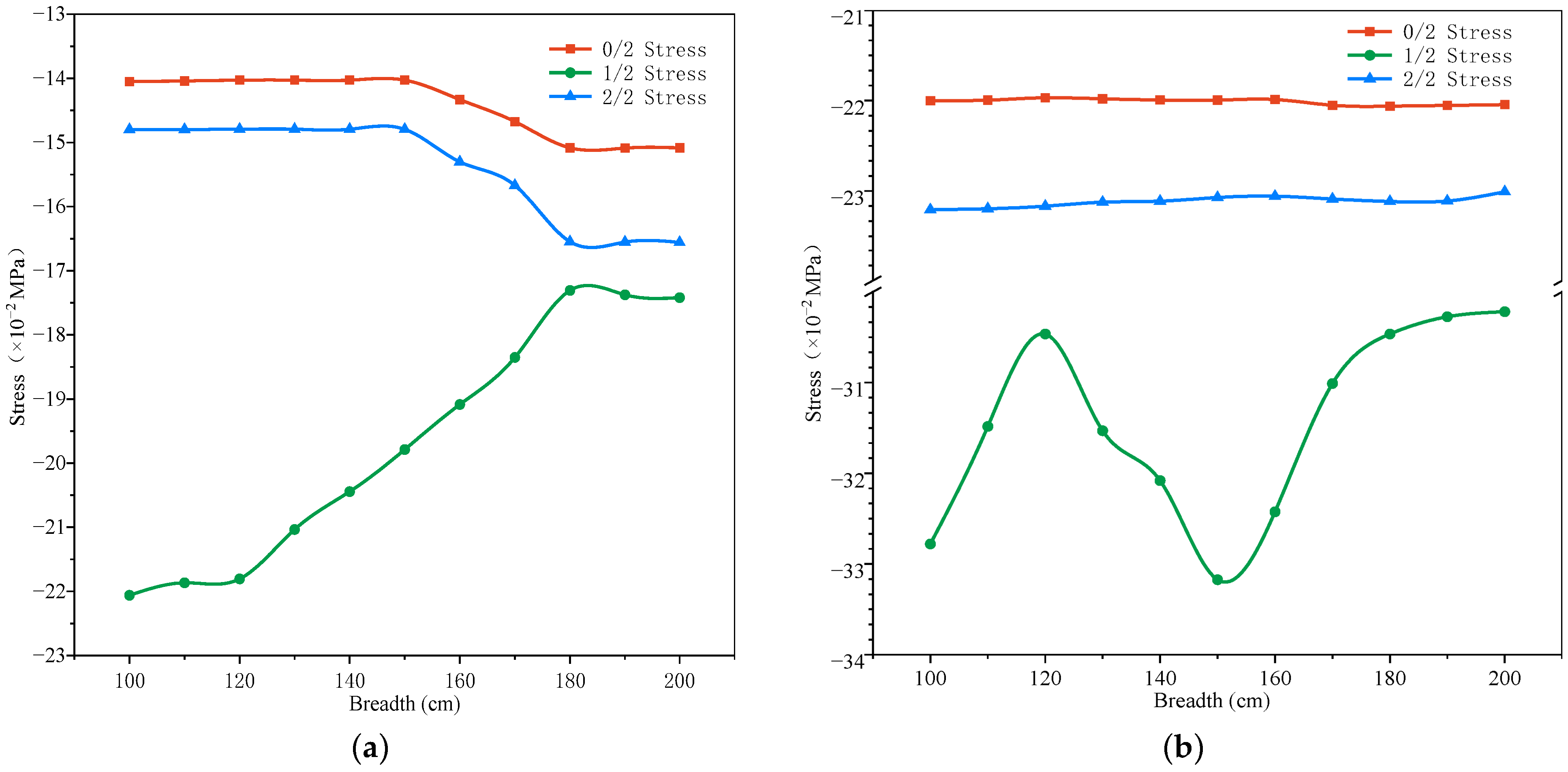

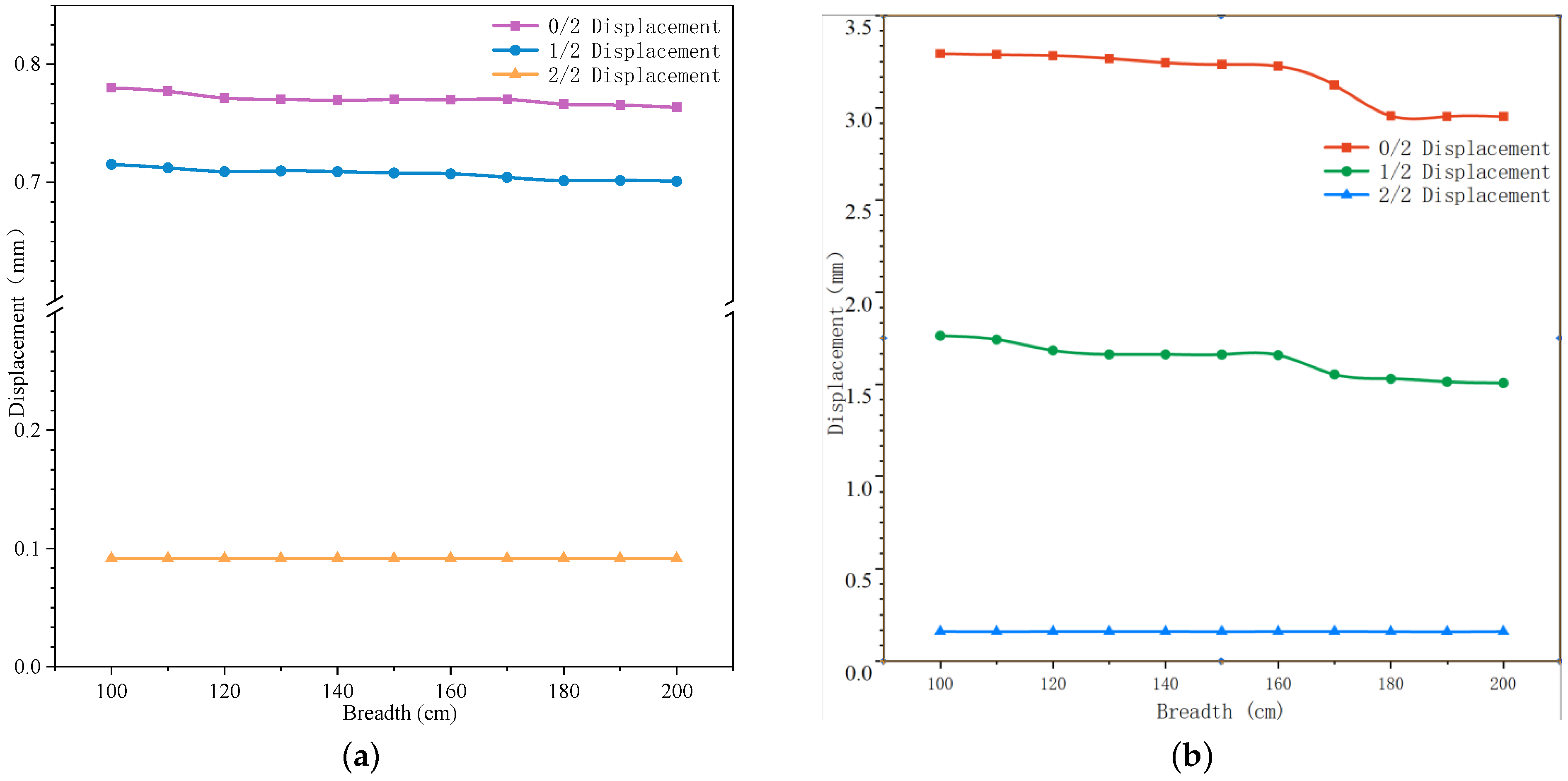

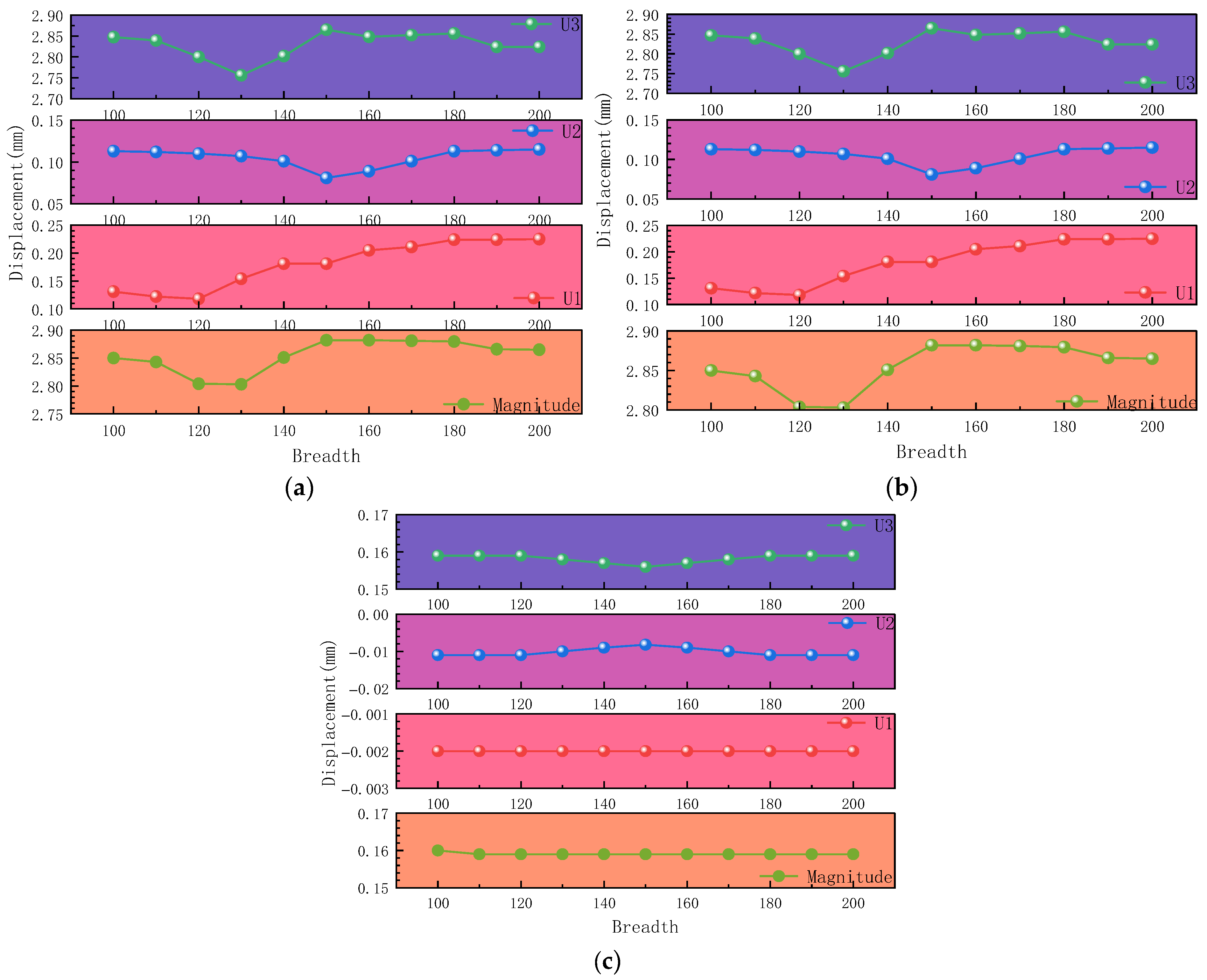

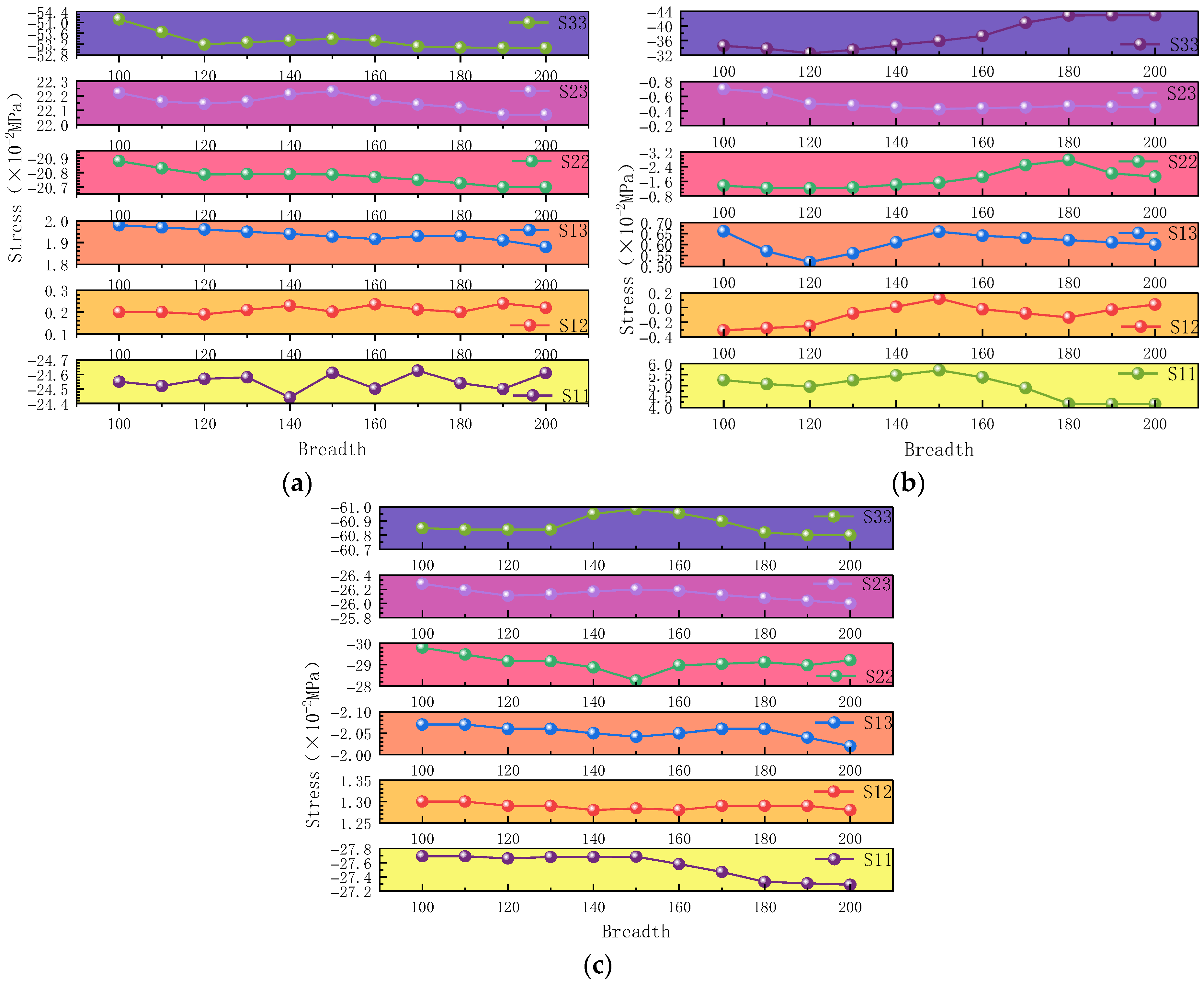

2.3.2. Simulation Under the Action of Class A Dead Load

2.3.3. Simulation Under Class B Permanent Loads

2.4. Influence Function of Carbon Fiber Fabric Width

- (1)

- Type A Dead Load:

f(x) = −1.247 × 10−5x2 + 0.0336x − 14.285 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = 2.15 × 10−5x2 − 0.1105x − 22.328 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = −6.71 × 10−5x2 − 0.0652x − 15.278 (2/2 Stress) - (2)

- Type B Dead Load:

f(x) = 3.64 × 10−6x2 − 0.0034x − 21.451 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = −1.04 × 10−5x2 + 0.0057x − 32.689 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = 1.55 × 10−5x2 − 0.0108x − 22.726 (2/2 Stress)

- (1)

- Type A Dead Load:

f(x) = 1.1543 × 10−6x2 − 0.0021x − 0.9143 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = −3.5714 × 10−6x2 + 0.0076x − 0.02 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = 0.0092 (2/2 Stress) - (2)

- Type B Dead Load:

f(x) = −6.9 × 10−4x2 + 0.1425x − 0.64 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = −2.82 × 10−5x2 + 0.0105x − 0.382 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = −1.81 × 10−5x2 + 0.0039x + 1.73 (2/2 Stress)

3. Study on the Influence of Outer Steel Plate Width

3.1. Establishment of Finite Element Simulation for Outer Steel Plate Strengthening

3.2. Simulation of Outer Steel Plate Strengthening

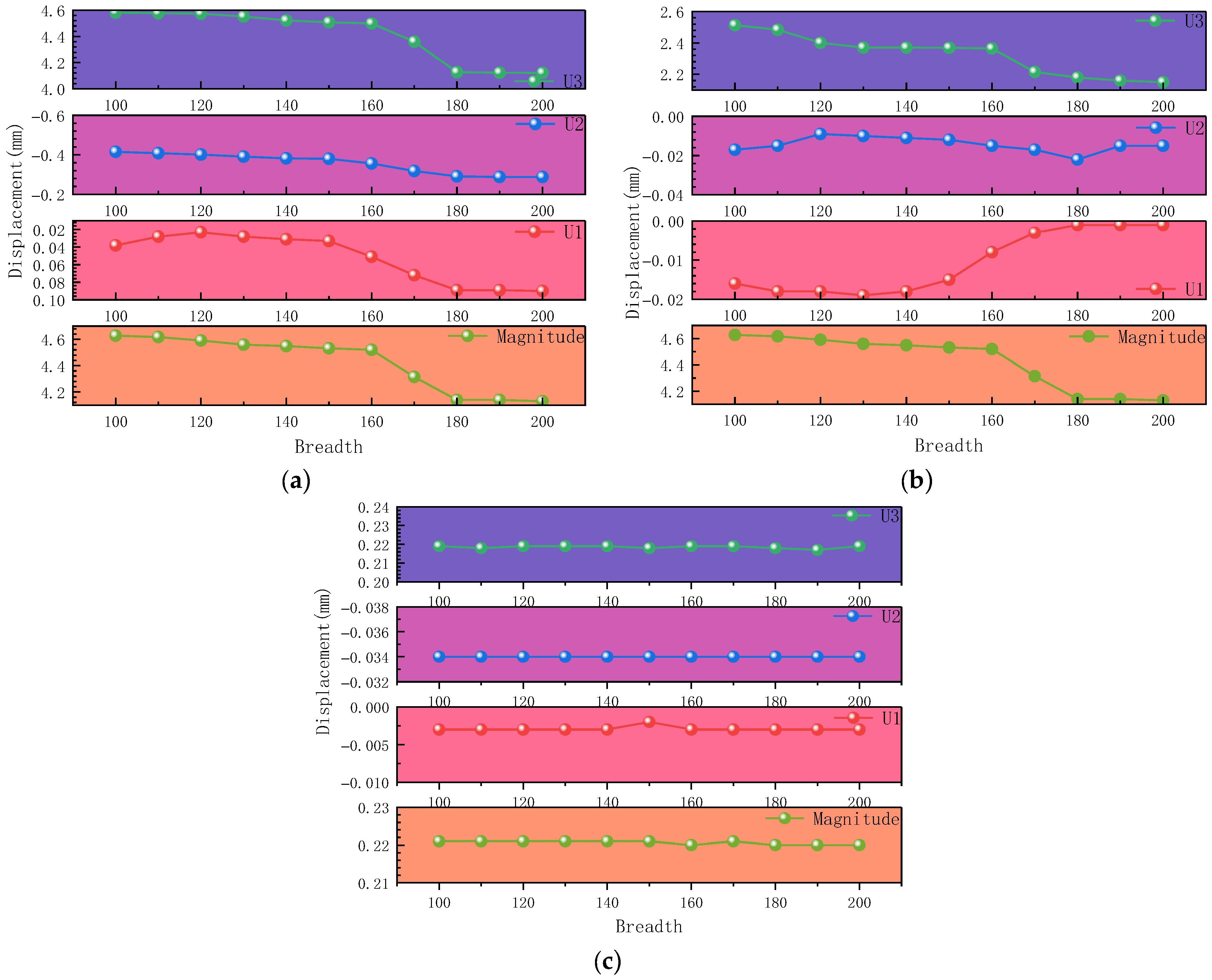

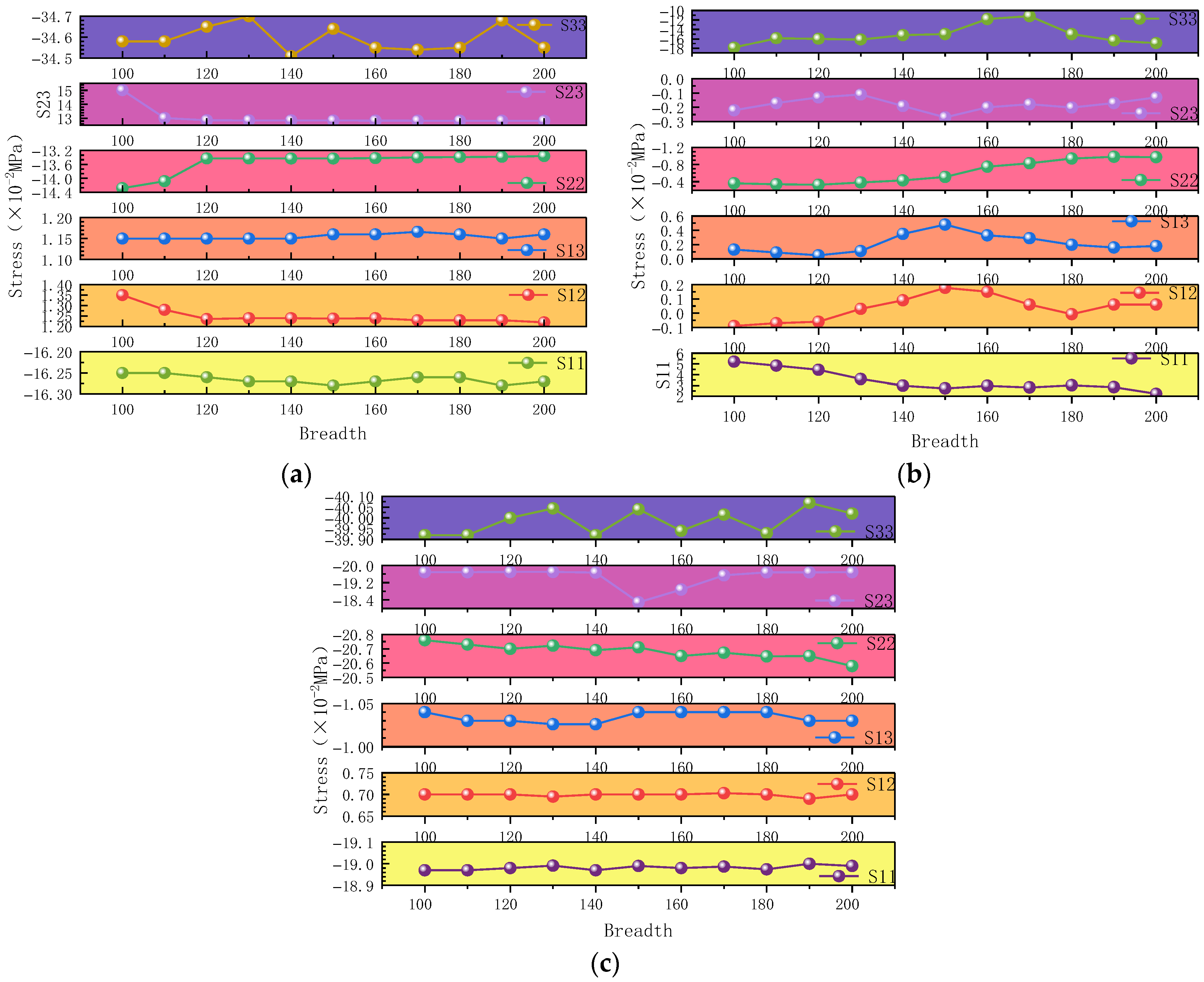

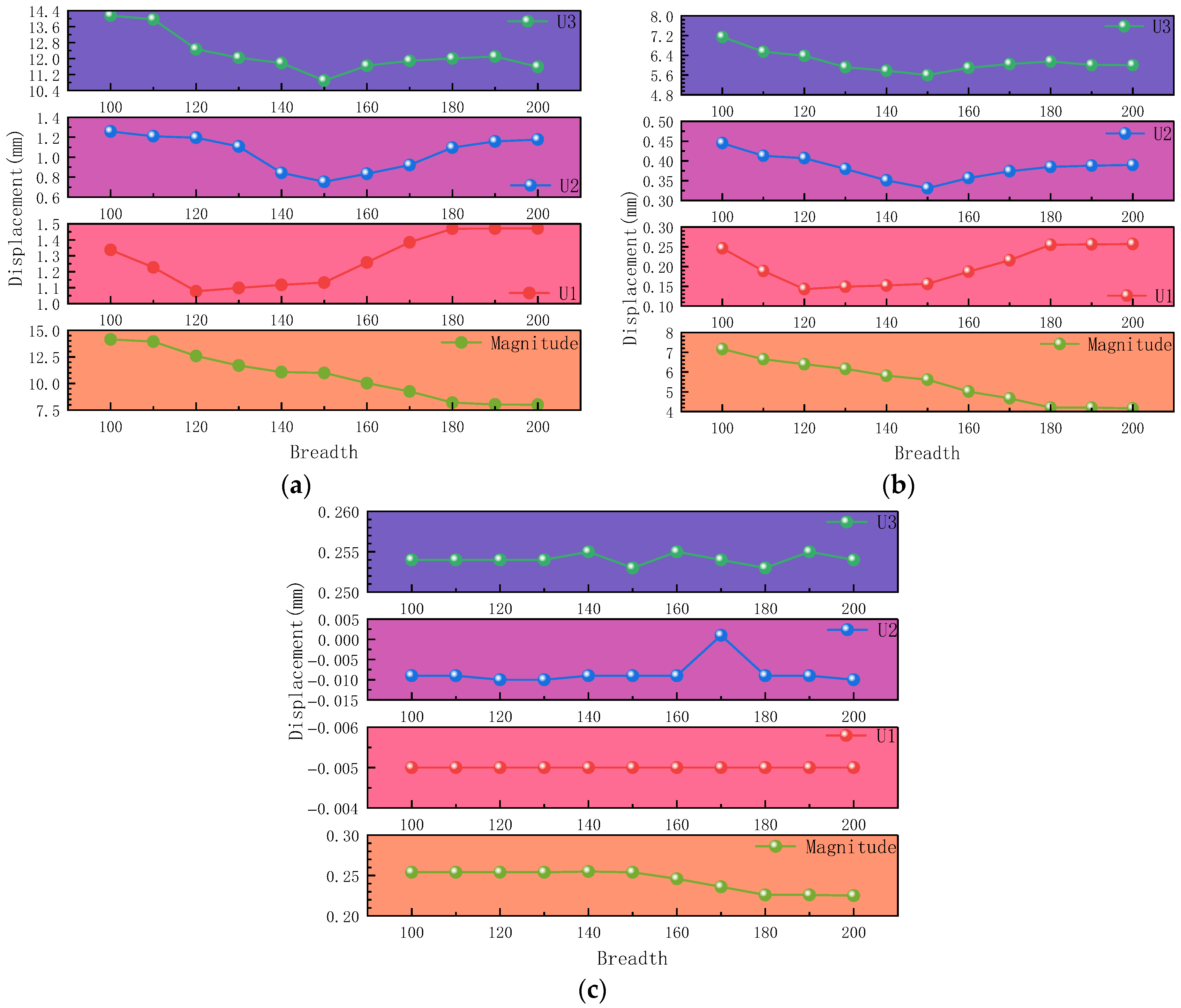

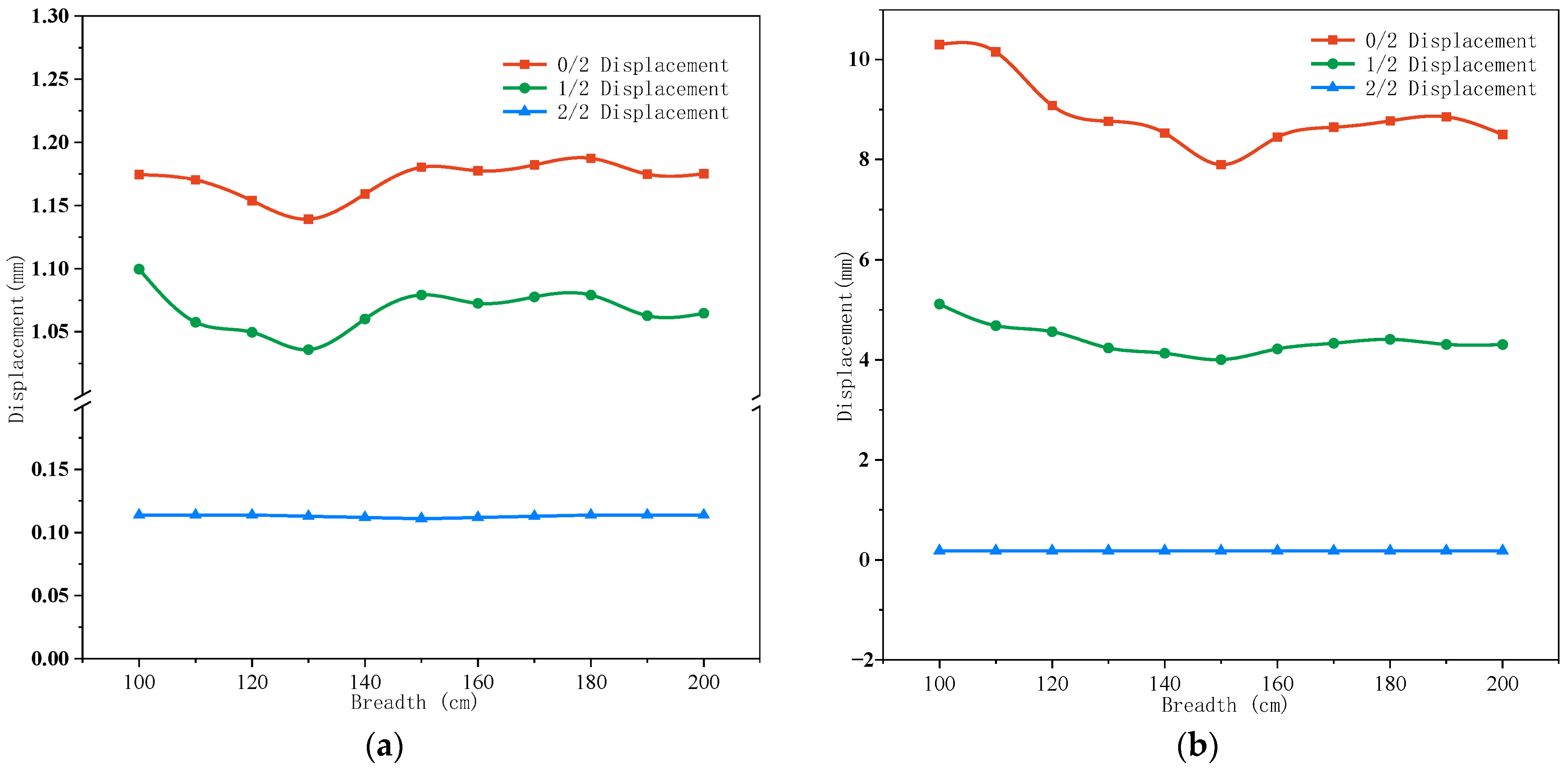

3.2.1. Simulation Under Type A Dead Load

3.2.2. Simulation Under Type B Dead Load

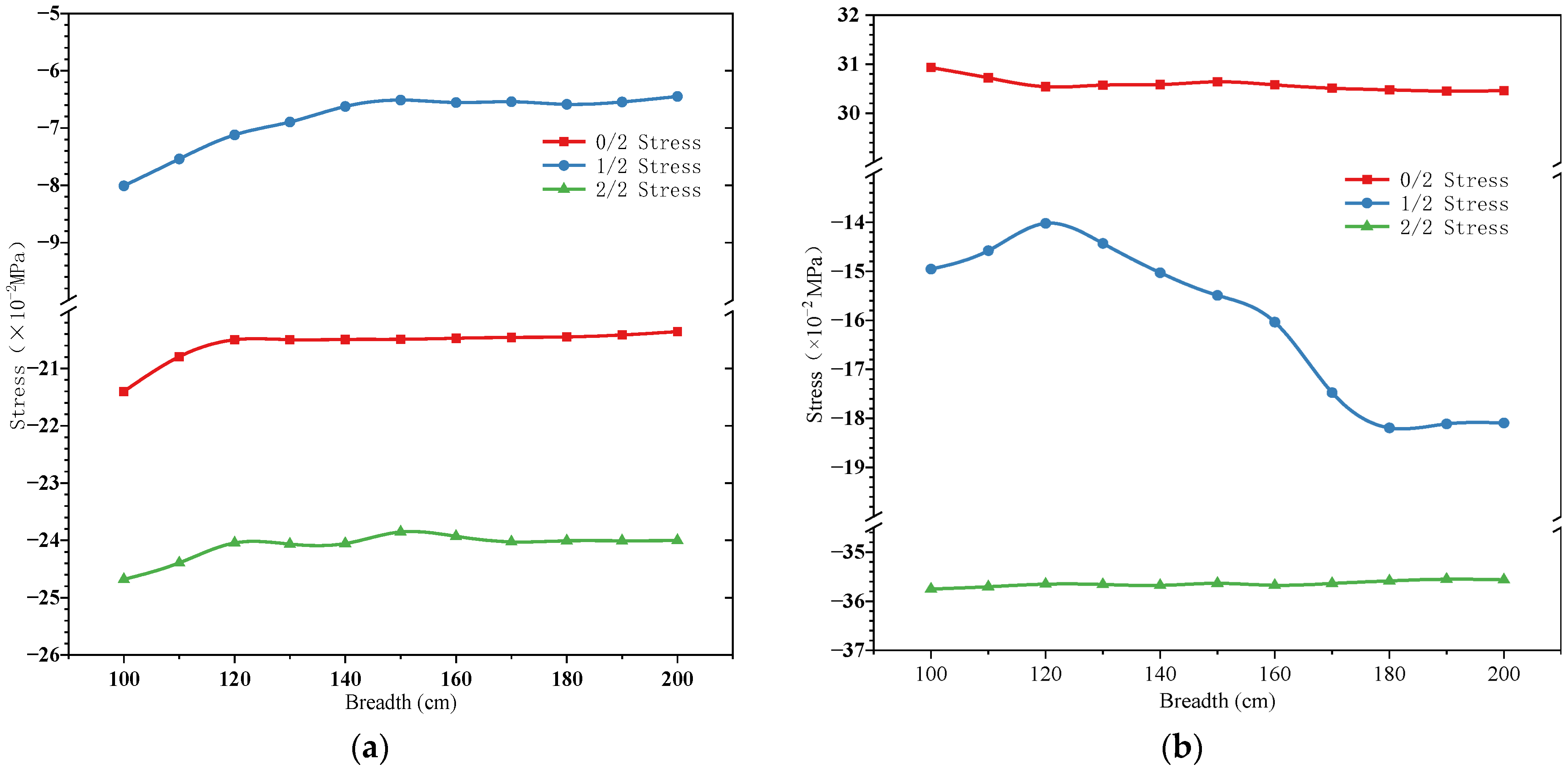

3.3. Influence Function of Steel Plate Width

- (1)

- Type A Dead Load:

f(x) = −4.86 × 10−4x2 + 0.0942x − 22.1 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = 0.0004x2 − 0.1405x − 14.84 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = −7.196 × 10−5x2 − 0.0032x − 24.75 (2/2 Stress) - (2)

- Type B Dead Load:

f(x) = −5.663 × 10−6x2 + 5.359 × 10 − 3x + 29.39 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = −1.346 × 10−2x2 + 2.076x − 57.52 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = −1.68 × 10−3x2 + 0.248x − 35.35 (2/2 Stress)

- (1)

- Type A Dead Load:

f(x) = −1.761 × 10−5x2 + 0.0034x + 1.045 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = −6.648 × 10−6x2 + 2.488 × 10 − 4x + 1.078 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = −3.551 × 10−7x2 + 7.28 × 10 − 5x + 0.11 (2/2 Stress) - (2)

- Type B Dead Load:

f(x) = 3.079 × 10−4x2 + 0.1781x − 232.5 (0/2 Stress) f(x) = −1.581 × 10−4x2 + 0.06149x − 610.4 (1/2 Stress) f(x) = −3.611 × 10−7x2 + 6.372 × 10 − 5x + 0.1482 (2/2 Stress)

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Strengthening width significantly affects the structural response, with the most pronounced effect observed at the pier’s mid-height (L/2) section. Both stress distribution and displacement variations show substantial sensitivity to width changes under different loading conditions.

- (2)

- The width–effectiveness relationship demonstrates a positive but nonlinear characteristic. While wider strengthening generally enhances performance, an optimal width exists beyond which marginal benefits diminish due to factors such as material self-weight and stress redistribution.

- (3)

- The developed weighted analysis methodology, integrating multi-directional stress and displacement data based on structural safety relevance, provides a more comprehensive assessment framework than conventional single-parameter evaluations.

- (4)

- Practical design tools have been established through fitted formulas for both CFRP and steel jacket strengthening methods within the 100–200 cm width range, offering direct guidance for engineering applications against rockfall impacts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cain, S.; Alessandro, P.; Allan, S. Seismic Behavior of Concrete Bridge Piers Reinforced with Steel or GFRP Bars. J. Compos. Constr. 2023, 27, 04023015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, G.; Bruggi, A.; Urso, S.; Quaini, M.; Penna, A. Cyclic shear-compression tests on two stone masonry piers strengthened with CRM and FRCM. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2023, 44, 2214–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T. Research on the Seismic Performance of Full Bridges with Carbon Fiber Material Reinforced Post-Earthquake Piers. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y. Dynamic Response of SRP-Reinforced Precast Segmental Piers under Vehicle Impact. J. Vib. Eng. 2021, 34, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.; Yuan, S.; Zhuo, W.; He, Z.; Liu, Z. Seismic retrofitting of rectangular bridge piers using ultra-high performance fiber reinforced concrete jackets. Compos. Struct. 2019, 228, 111367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wu, Y.; Luo, H.; Hu, X. Seismic Vulnerability Analysis of Double-Deck Viaduct Frame Piers Reinforced with CFRP and Outer Steel Composites. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, A.; Zhu, D.; Yang, K.; Shen, X.; Xie, X. Experimental Study on the Bearing Capacity of Steel-Concrete Composite Reinforced Beams. J. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2023, 45, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.Y.; Kang, J.F.; Zhu, J.S. Constitutive Relationship of Ultra-High Performance Concrete under Uniaxial Compression. J. Southeast Univ. 2017, 47, 369–376. [Google Scholar]

- Piscesa, B.; Attard, M.M.; Samani, A.K.; Tangaramvong, S. Plasticity Constitutive Model for Stress-Strain Relationship of Confined Concrete. ACI Struct. J. 2017, 114, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaky, I.A.; Elamary, A.S.; Alharthi, Y.M. Experimental and numerical investigation on the flexural performance of RC slabs strengthened with EB/NSM CFRP strengthening and bonded reinforced HSC layers. Eng. Struct. 2023, 289, 116338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, J.T.; Matamoros, B.A. Constitutive Modeling and Overstrength Factors for Reinforcing Steel. ACI Struct. J. 2019, 116, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Research on Impact Force Calculation of Double Pillar Pier impacted by Rolling stones in Mountainous Area. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University of Science and Technology, Chongqing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Harzallah, S.; Chabaat, M.; Saidani, M.; Moussaoui, M. Numerical investigation of the seismic vulnerability of bridge piers strengthened with steel fibre reinforced concrete (SFRC) and carbon fibre composites (CFC). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H. Research on Strengthening Methods for Local Damage of Piers Caused by Rockfall Impacts. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing University of Science and Technology, Chongqing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.-J.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, L.-M.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.-W. Impact Force Algorithm and Parameters of Rolling Stone Impact Pier in Mountain Area. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 5542305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Fan, Q.; Azar, S.M.; Alyousef, R.; Yousif, S.T.; Wakil, K.; Jermsittiparsert, K.; Ho, L.S.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Alaskar, A. Computational parameter identification of strongest influence on the shear resistance of reinforced concrete beams by fiber strengthening polymer. Pap. Present. Struct. 2020, 27, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.C.; Gan, V.J. Reinforced concrete structural design optimization: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 120623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG/T J22-2008; Design Code for Reinforcement of Highway Bridges. Industry standard—Transportation China: Beijing, China, 2008.

| Case Number | Damage Status |

|---|---|

| SBefore Damage | Concrete surface is smooth and intact |

| SBefore Strengthening | Concrete surface spalling, obvious impact point indentation, damage range 7 × 8, 18 mm deep |

| SCFRP Strengthening | Slight impact point indentation, surface is smooth and intact |

| Stress Direction | Weight | Stress Direction | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| S11 | 0.15 | U1 | 0.10 |

| S22 | 0.10 | U2 | 0.20 |

| S33 | 0.40 | U3 | 0.70 |

| S12 | 0.10 | ||

| S13 | 0.10 | ||

| S23 | 0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Ling, L.; Luo, H.; Wu, L.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Y. Strengthening Width on Local Damage to Circular Piers Caused by Rolling Boulder Impacts. Buildings 2025, 15, 4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234347

Wang Z, Li J, Ling L, Luo H, Wu L, Zhou X, Wang Y. Strengthening Width on Local Damage to Circular Piers Caused by Rolling Boulder Impacts. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234347

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zijian, Junjie Li, Ling Ling, Haoran Luo, Linming Wu, Xingyu Zhou, and Yi Wang. 2025. "Strengthening Width on Local Damage to Circular Piers Caused by Rolling Boulder Impacts" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234347

APA StyleWang, Z., Li, J., Ling, L., Luo, H., Wu, L., Zhou, X., & Wang, Y. (2025). Strengthening Width on Local Damage to Circular Piers Caused by Rolling Boulder Impacts. Buildings, 15(23), 4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234347