Universal Empirical Criterion for Martensitic Transformation Temperature in Ni-Mn-Based Heusler Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

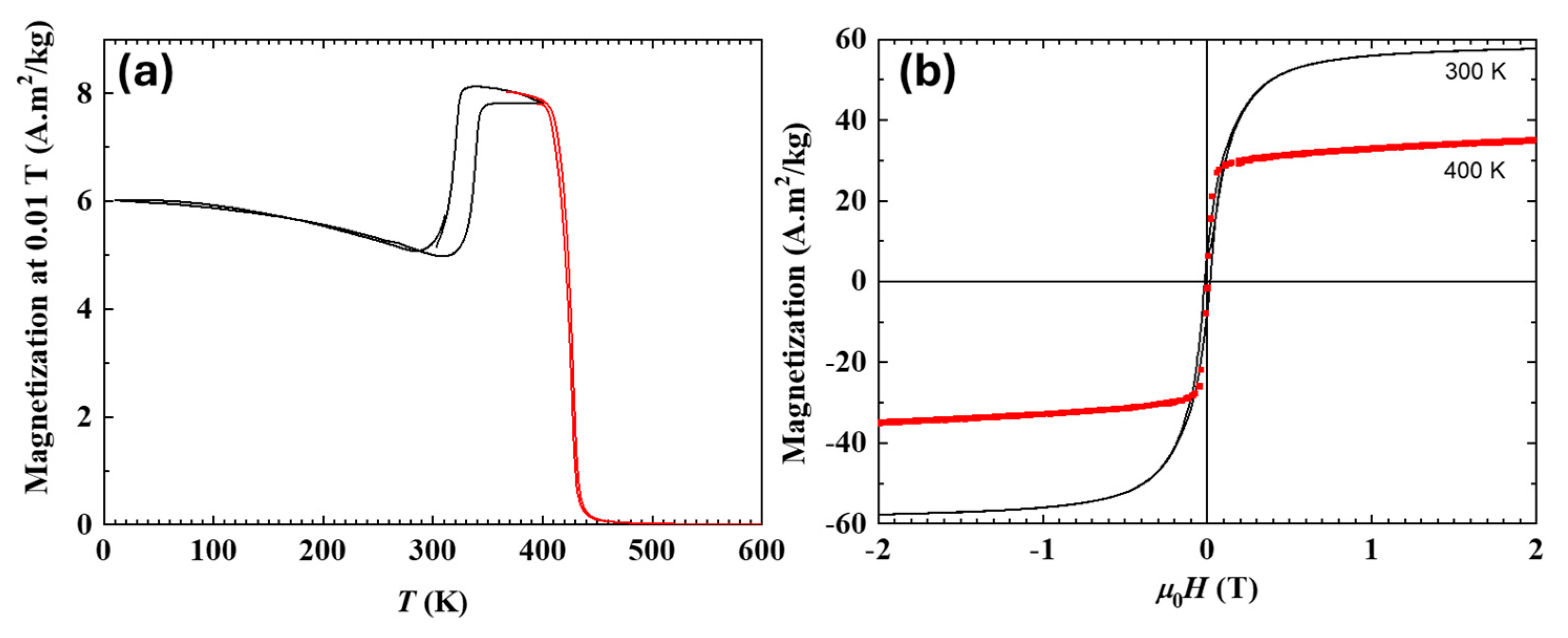

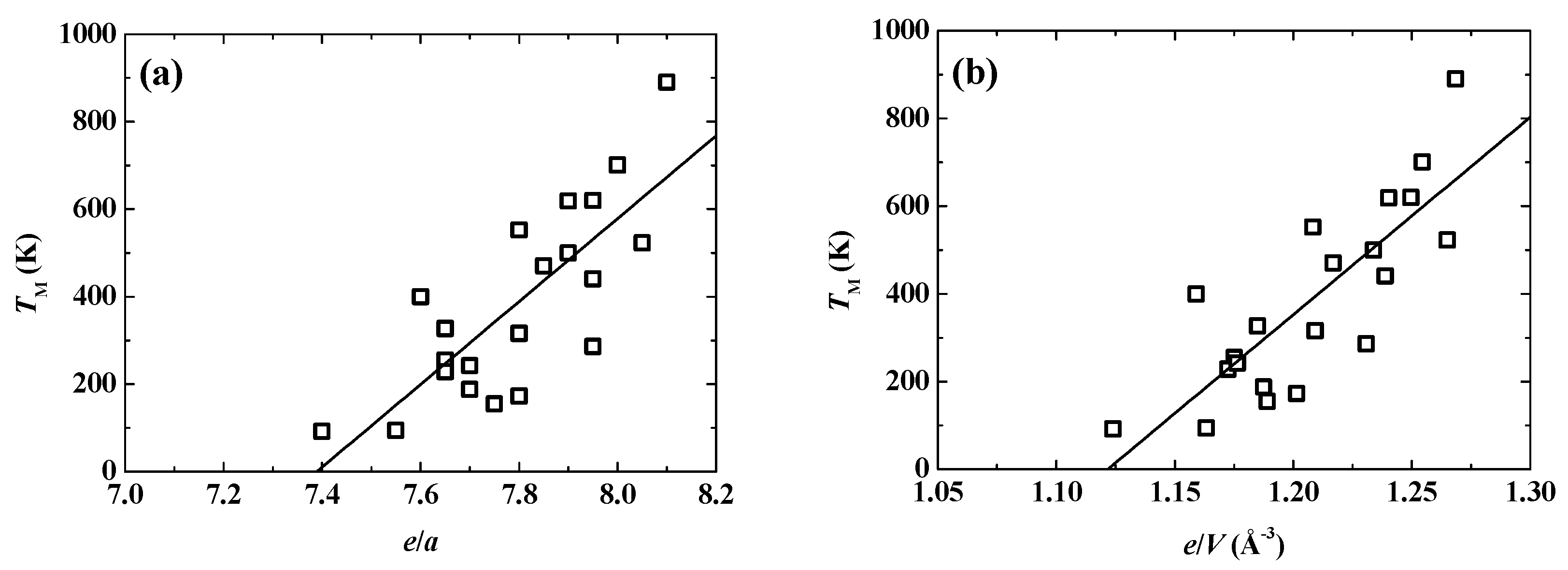

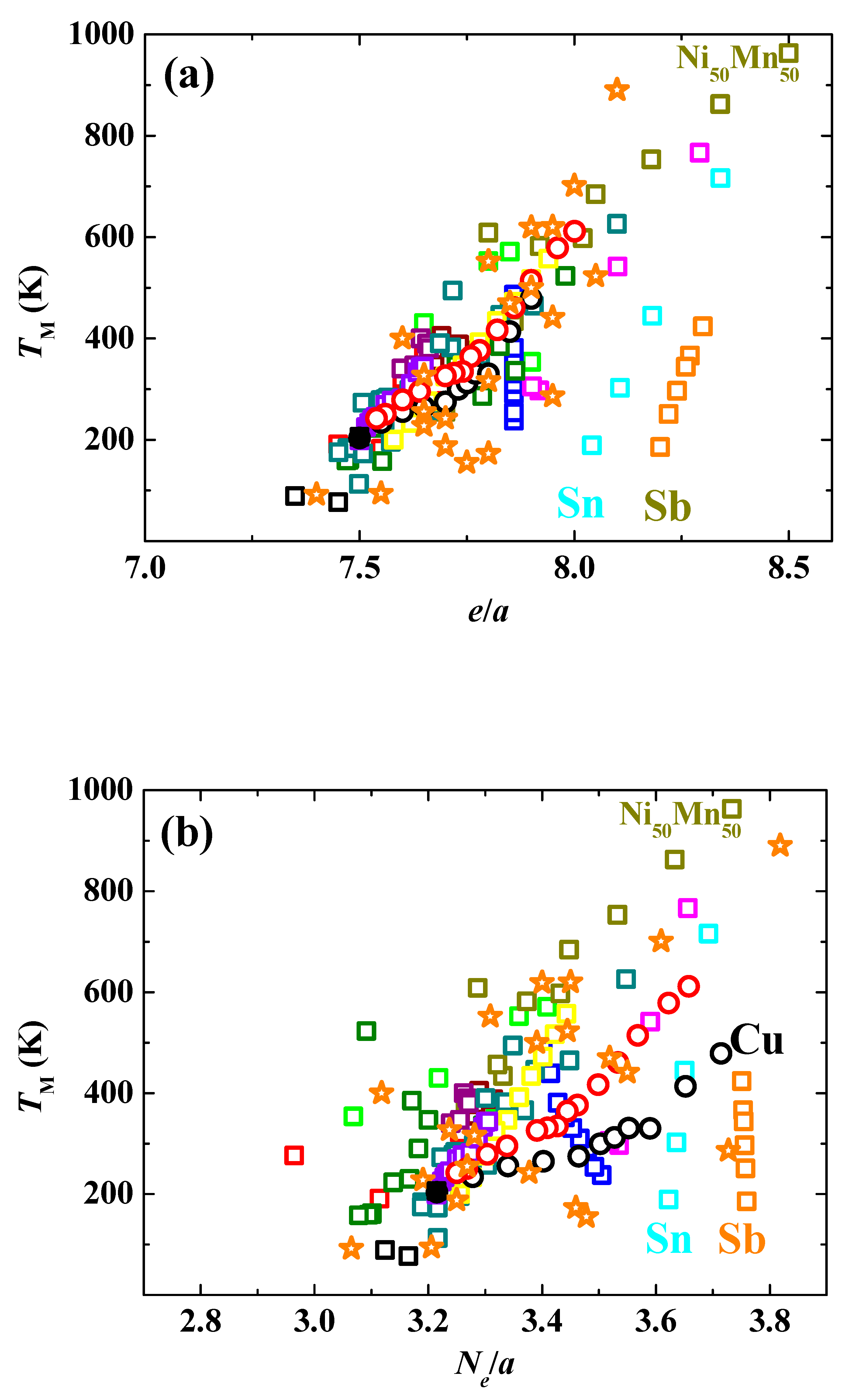

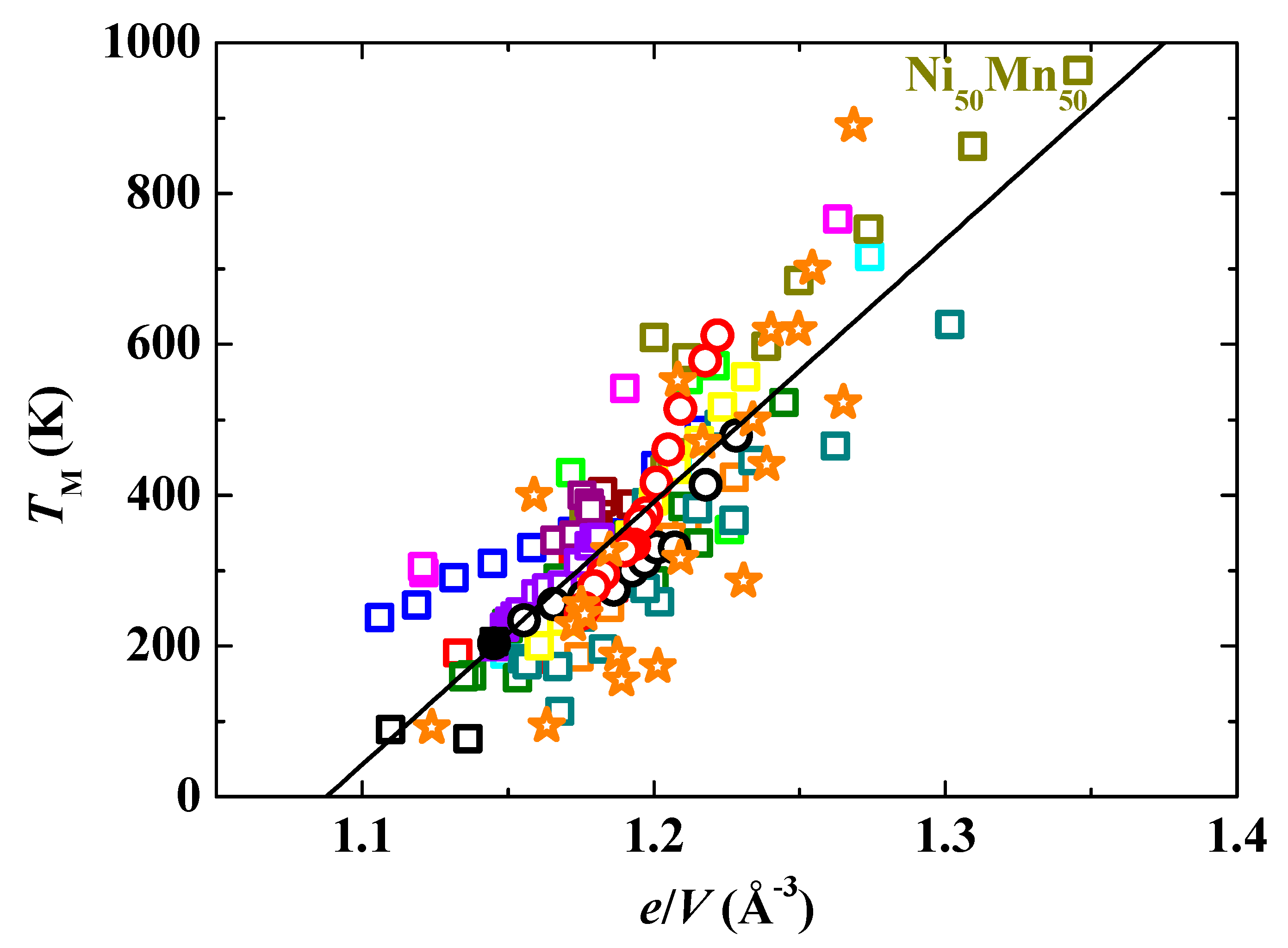

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coey, J.M.D. Magnetism and Magnetic Materials; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Heczko, O.; Sozinov, A.; Ullakko, K. Giant field-induced reversible strain in magnetic shape memory NiMnGa alloy. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 3266–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, L.; Heczko, O. Superelastic response of Ni-Mn-Ga martensite in magnetic fields and a simple model. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2003, 39, 3402–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.K.; Chiu, W.T.; Tahara, M.; Nohira, N.; Chernenko, V.; Lanceros-Mendez, S.; Hosoda, H. An unusual approach significantly improving the magnetostrain performance of Ni-Mn-Ga composite materials. Scr. Mater. 2025, 261, 116624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibel, F.; Gottschall, T.; Taubel, A.; Fries, M.; Skokov, K.P.; Terwey, A.; Keune, W.; Ollefs, K.; Wende, H.; Farle, M.; et al. Hysteresis design of magnetocaloric materials—From basic mechanisms to applications. Energy Technol. 2018, 6, 1397–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvílová, M.; Klicpera, M.; Malý, F.; Valenta, J.; Veis, M.; Colman, R.H.; Heczko, O. Systematic experimental search for Fe2YZ Heusler compounds predicted by ab-initio calculation. Intermetallics 2021, 131, 107073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, A.; de Châtel, P.; de Boer, F. Cohesion in alloys—Fundamentals of a semi-empirical model. Phys. B + C 1980, 100, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramudu, M.; Kumar, A.S.; Seshubai, V.; Rajasekharan, T. Correlation of martensitic transformation temperatures of Ni- Mn-Ga/Al-X alloys to non-bonding electron concentration. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 73, 012074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecký, V.; Rameš, M.; Veřtát, P.; Colman, R.H.; Heczko, O. Full Variation of Site Substitution in Ni-Mn-Ga by Ferromagnetic Transition Metals. Metals 2021, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A.; Nilsén, F.; Rameš, M.; Colman, R.H.; Veřtát, P.; Kmječ, T.; Straka, L.; Müllner, P.; Heczko, O. Systematic Trends of Transformation Temperatures and Crystal Structure of Ni–Mn–Ga–Fe–Cu Alloys. Shape Mem. Superelasticity 2020, 6, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heczko, O.; Rameš, M.; Kopecký, V.; Veřtát, P.; Varga, M.; Straka, L. Magnetic and transformation properties of Ni2MnGa combinatorically substituted with 5 at.% of transition elements from Cr to Cu–Experimental insight. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2024, 589, 171510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Li, G.T.; Wu, Z.G.; Ma, X.Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G.H. Tailoring martensitic transformation and martensite structure of NiMnIn alloy by Ga doping In. J. Alloys. Compd. 2012, 535, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenke, T.; Acet, M.; Wassermann, E.F.; Moya, X.; Mañosa, L.; Planes, A. Martensitic transitions and the nature of ferromagnetism in the austenitic and martensitic states of Ni-Mn-Sn alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 014412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenke, T.; Acet, M.; Wassermann, E.F.; Moya, X.; Mañosa, L.; Planes, A. Ferromagnetism in the austenitic and martensitic states of Ni-Mn-In alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 174413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutou, Y.; Imano, Y.; Koeda, N.; Omori, T.; Kainuma, R.; Ishida, K.; Oikawa, K. Magnetic and martensitic transformations of NiMnX (X = In, Sn, Sb) ferromagnetic shape memory alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 4358–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainuma, R.; Nakano, H.; Ishida, K. Martensitic Transformations in NiMnAl Phase Alloys. Metal. Mater. Trans. A 1996, 27, 4153–4162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfs, K.; Wimpory, R.C.; Petry, W.; Schneider, R. Effect of alloying Ni-Mn-Ga with Cobalt on thermal and structural properties. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2010, 251, 012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Kanomata, T.; Kainuma, R. Specific heat and entropy change during martensitic transformation in Ni50Mn50-xGax ferromagnetic shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 2014, 79, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khovailo, V.V.; Oikawa, K.; Abe, T.; Takagi, T. Entropy change at the martensitic transformation in ferromagnetic shape memory alloys Ni2+xMn1−xGa. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 8483–8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernenko, V.A.; Cesari, E.; Kokorin, V.V.; Vitenko, I.N. The development of new ferromagnetic shape memory alloys in Ni-Mn-Ga system. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1995, 33, 1239–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, M.; Endo, K.; Kudo, N.; Kanomata, T.; Nishihara, H.; Shishido, T.; Umetsu, R.Y.; Nagasako, M.; Kainuma, R. Martensitic transition, ferromagnetic transition, and their interplay in the shape memory alloys Ni2Mn1−xCuxGa. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 214423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, K.; Kanomata, T.; Kimura, A.; Kataoka, M.; Nishihara, H.; Umetsu, R.Y.; Obara, K.; Shishido, T.; Nagasako, M.; Kainuma, R.; et al. Magnetic phase diagram of the ferromagnetic shape memory alloys Ni2MnGa1−xCux. Mater. Sci. Forum 2011, 684, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yoshida, Y.; Omori, T.; Kanomata, T.; Kainuma, R. Magnetic properties and phase diagram of Ni50Mn50-xGax/2Inx/2 magnetic shape memory alloys. Shape Mem. Superelasticity 2016, 2, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejpek, P.; Proschek, P.; Straka, L.; Heczko, O. Dependence of martensite transformation temperature on magnetic field in Ni2MnGa and Ni2MnGa0.95In0.05 single crystals. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 908, 164514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q.; Lu, X.; Wang, D.Y.; Qin, Z.X. The effect of Co–doping on martensitic transformation temperatures in Ni–Mn–Ga Heusler alloys. Smart Mater. Struct. 2008, 17, 065030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belosludtseva, E.S.; Kuranova, N.N.; Marchenkova, E.B.; Popov, A.G.; Pushin, V.G. Effect of gallium alloying on the structure, the phase composition, and the thermoelastic martensitic transformations in ternary Ni–Mn–Ga alloys. Tech. Phys. 2016, 61, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, T.; Felser, C.; Parkin, S.S.P. Simple rules for the understanding of Heusler compounds. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2011, 39, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Marioni, M.; Bono, D.; Allen, S.M.; O’Handley, R.C.; Hsu, T.Y. Empirical mapping of Ni–Mn–Ga properties with composition and valence electron concentration. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 91, 8222–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heczko, O.; Straka, L. Compositional dependence of structure, magnetization and magnetic anisotropy in Ni–Mn–Ga magnetic shape memory alloys. J. Magn. Magn. Mat. 2004, 272, 2045–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Parra, D.E.; Alvarado-Hernandez, F.; Ayala, O.; Ochoa-Gamboa, R.A.; Flores-Zuniga, H.; Rios-Jara, D. The effect of Fe addition on the transformation temperatures, lattice parameter and magnetization saturation of Ni52.5−XMn23Ga24.5FeX ferromagnetic shape memory alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 464, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, H.B.; Zheng, Y.F.; Cai, W.; Zhao, L.C. Effect of Fe addition on transformation temperatures and hardness of NiMnGa magnetic shape memory alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 2005, 40, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, D.; Hernández, F.A.; Flores-Zúñiga, H.; Moya, X.; Mañosa, L.; Planes, A.; Aksoy, S.; Acet, M.; Krenke, T. Phase diagram of Fe-doped Ni-Mn-Ga ferromagnetic shape-memory alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 184103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entel, P.; Siewert, M.; Gruner, M.E.; Herper, H.C.; Comtesse, D.; Arróyave, R.; Singh, N.; Talapatra, A.; Sokolovskiy, V.V.; Buchelnikov, V.D.; et al. Complex magnetic ordering as a driving mechanism of multifunctional properties of Heusler alloys from first principles. Eur. Phys. J. B 2013, 86, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M.; Ríos, M.; Lázpita, P.; Chernenko, V.; Salazar, D.; Szczerba, M.J. Transformation behavior and magnetic properties of Ni-Mn-Ga melt-spun ribbons tuned by tandem of Co and Cu dopants. J. Alloy. Compd. 2025, 1046, 184784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelený, M.; Straka, L.; Sozinov, A.; Heczko, O. Transformation Paths from Cubic to Low-Symmetry Structures in Heusler Ni2MnGa Compound. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.; Guo, K.; Liu, D.; Gu, J.; Morley, N.; Ma, Q.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Esling, C.; et al. An alloying strategy for tuning magnetism, thermal hysteresis, and mechanical properties in Ni-Mn-Sn-based Heusler alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 2024, 979, 173593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Shi, D.; Zhang, K.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Ma, T.; Wang, C.; Wen, Q.; Tan, C. Machine-learning model for prediction of martensitic transformation temperature in NiMnSn-based ferromagnetic shape memory alloys. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 215, 111811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.C.; Cao, K.Y.; Ma, R.N.; Wang, J.B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.Y.; Zhou, C.; Tian, F.H.; Fang, M.X.; Yang, S. Accurate prediction of magnetocaloric effect in NiMn-based Heusler alloys by prioritizing phase transitions through explainable machine learning. Rare Metals. 2025, 44, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haschke, M.; Haschke, M. (Eds.) Laboratory Micro-X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy. In Instrumentation and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 157–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Lin, P.T.; Tsai, C.W. High-temperature martensitic transformation of CuNiHfTiZr high-entropy alloys. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 19598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Valence Electron Number e/a | NWS1/3 | Covalent Atomic Radius (pm) | Metallic Radius (pm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr | 6 | 1.73 | 122 | 128 |

| Mn | 7 | 1.61 | 119 | 127 |

| Fe | 8 | 1.77 | 116 | 126 |

| Co | 9 | 1.75 | 112 | 128 |

| Ni | 10 | 1.75 | 110 | 124 |

| Cu | 11 | 1.47 | 112 | 128 |

| Ga | 3 | 1.31 | 124 | 135 |

| In | 3 | 1.17 | 142 | 167 |

| Al | 3 | 1.39 | 126 | 143 |

| Sn | 4 | 1.24 | 140 | - |

| Sb | 5 | 1.26 | 140 | - |

| Alloy | e/a | Ne/a | e/Vcovalent (Å−3) | TM (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni45Mn25Ga20Fe5Cu5 | 7.80 | 3.46 | 1.20 | 173 |

| Ni45Mn30Ga20Co5 | 7.65 | 3.27 | 1.18 | 255 |

| Ni55Mn20Ga20Cr5 | 7.80 | 3.31 | 1.21 | 552 |

| Ni45Mn20Ga30Cr5 | 7.10 | 2.92 | 1.06 | n/a |

| Ni50Mn20Ga20Cr10 | 7.60 | 3.12 | 1.16 | 400 |

| Ni45Mn20Ga25Cr5Co5 | 7.40 | 3.06 | 1.12 | 92 |

| Ni50Mn20Ga20Fe5Cu5 | 7.95 | 3.55 | 1.24 | 441 |

| Ni50Mn20Ga20Cu10 | 8.10 | 3.82 | 1.27 | 902 |

| Ni50Mn20Ga20Co5Cu5 | 8.00 | 3.61 | 1.25 | 701 |

| Ni40Mn25Ga25Fe5Co5 | 7.35 | 3.06 | 1.11 | n/a |

| Ni50Mn15Ga25Fe5Co5 | 7.65 | 3.24 | 1.18 | 327 |

| Ni50Mn25Ga15Fe5Co5 | 8.05 | 3.44 | 1.26 | 523 |

| Ni50Mn20Ga20Fe10 | 7.80 | 3.28 | 1.21 | 316 |

| Ni45Mn25Ga20Fe5Co5 | 7.70 | 3.25 | 1.19 | 188 |

| Ni45Mn25Ga20Fe10 | 7.65 | 3.19 | 1.17 | 228 |

| Ni45Mn20Ga25Co10 | 7.55 | 3.21 | 1.16 | 94 |

| Ni45Mn20Ga25Fe5Co5 | 7.50 | 3.15 | 1.15 | n/a |

| Ni45Mn20Ga25Fe10 | 7.45 | 3.09 | 1.13 | n/a |

| Ni50Mn20Ga20Co10 | 7.90 | 3.40 | 1.24 | 619 |

| Ni55Mn20Ga20Co5 | 7.95 | 3.45 | 1.25 | 620 |

| Ni55Mn20Ga20Fe5 | 7.90 | 3.39 | 1.23 | 500 |

| Ni45Mn25Ga20Cr5Cu5 | 7.70 | 3.38 | 1.18 | 242 |

| Ni45Mn30Ga20Cu5 | 7.75 | 3.48 | 1.19 | 155 |

| Ni45Mn20Ga25Cr5Fe5 | 7.35 | 3.01 | 1.11 | n/a |

| Ni45Mn25Ga20Co5Cu5 | 7.85 | 3.52 | 1.22 | 470 |

| Ni45Mn25Ga20Cu10 | 7.95 | 3.73 | 1.23 | 286 |

| Ni50Mn25Ga25 | 7.50 | 3.21 | 1.15 | 206 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rameš, M.; Heczko, O. Universal Empirical Criterion for Martensitic Transformation Temperature in Ni-Mn-Based Heusler Alloys. Metals 2026, 16, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010064

Rameš M, Heczko O. Universal Empirical Criterion for Martensitic Transformation Temperature in Ni-Mn-Based Heusler Alloys. Metals. 2026; 16(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleRameš, Michal, and Oleg Heczko. 2026. "Universal Empirical Criterion for Martensitic Transformation Temperature in Ni-Mn-Based Heusler Alloys" Metals 16, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010064

APA StyleRameš, M., & Heczko, O. (2026). Universal Empirical Criterion for Martensitic Transformation Temperature in Ni-Mn-Based Heusler Alloys. Metals, 16(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010064