Modeling and Experimental Analysis of the Dislocation Structure Evolution During Deformation of High-Purity Aluminum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Experiment

2.1.1. Deformation

2.1.2. Data Acquisition and Post-Processing

2.1.3. Evaluation of GNDs

2.1.4. Subgrain/Cell Size Evaluation

2.2. Simulation

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

| Symbol | Name | Value | Unit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| strengthening coefficients for internal dislocations | _ | [64] | ||

| strengthening coefficients for wall dislocations | _ | [64] | ||

| Taylor factor | _ | [65,66] | ||

| shear modulus | MPa | [67,68] | ||

| Burgers vector | m | [69,70] | ||

| the saturation value of wall volume fraction | _ | [23] | ||

| the peak value of wall volume fraction | _ | [23] | ||

| A constant to determine the decrease rate of wall volume fraction | _ | [23] |

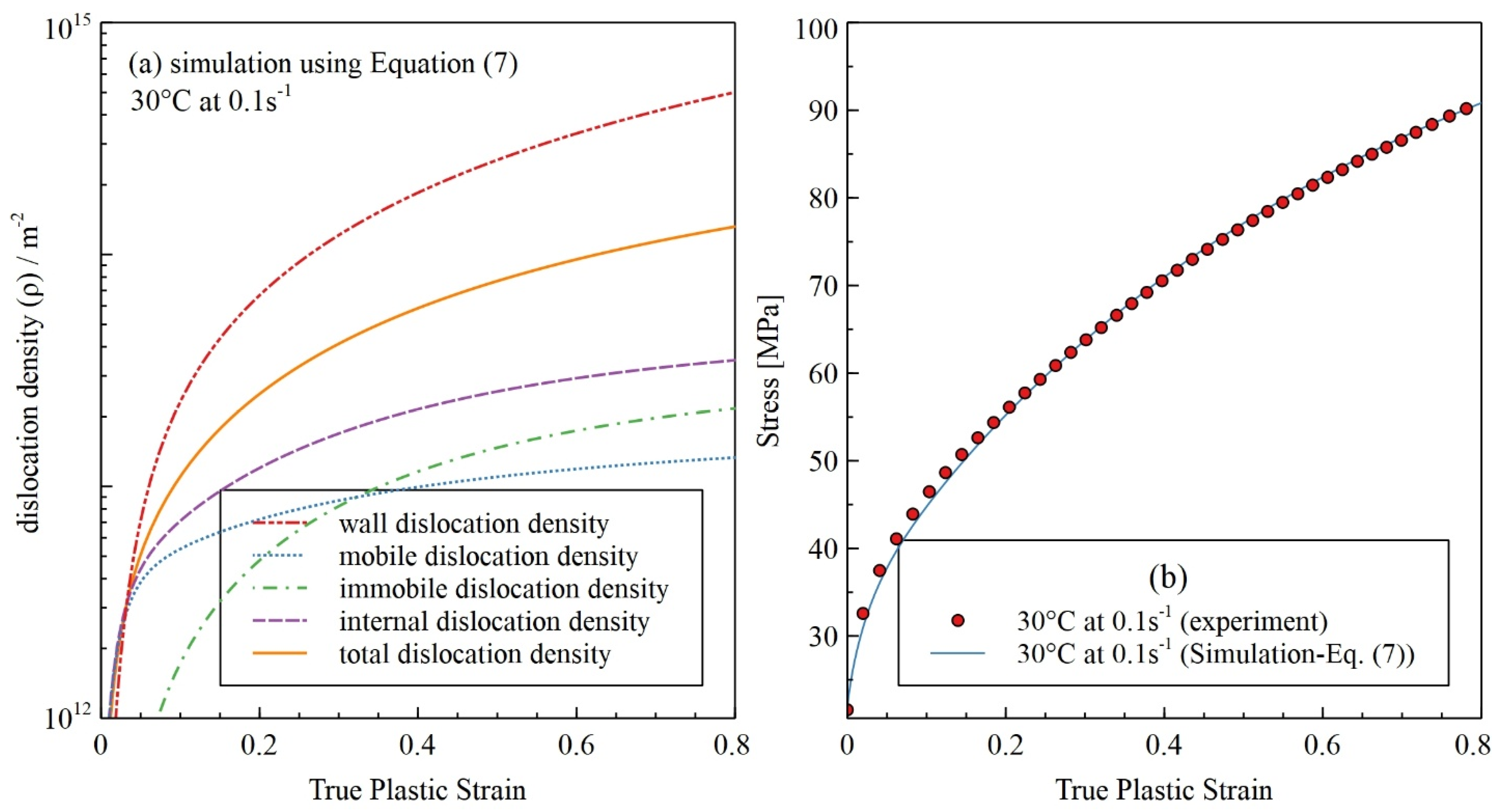

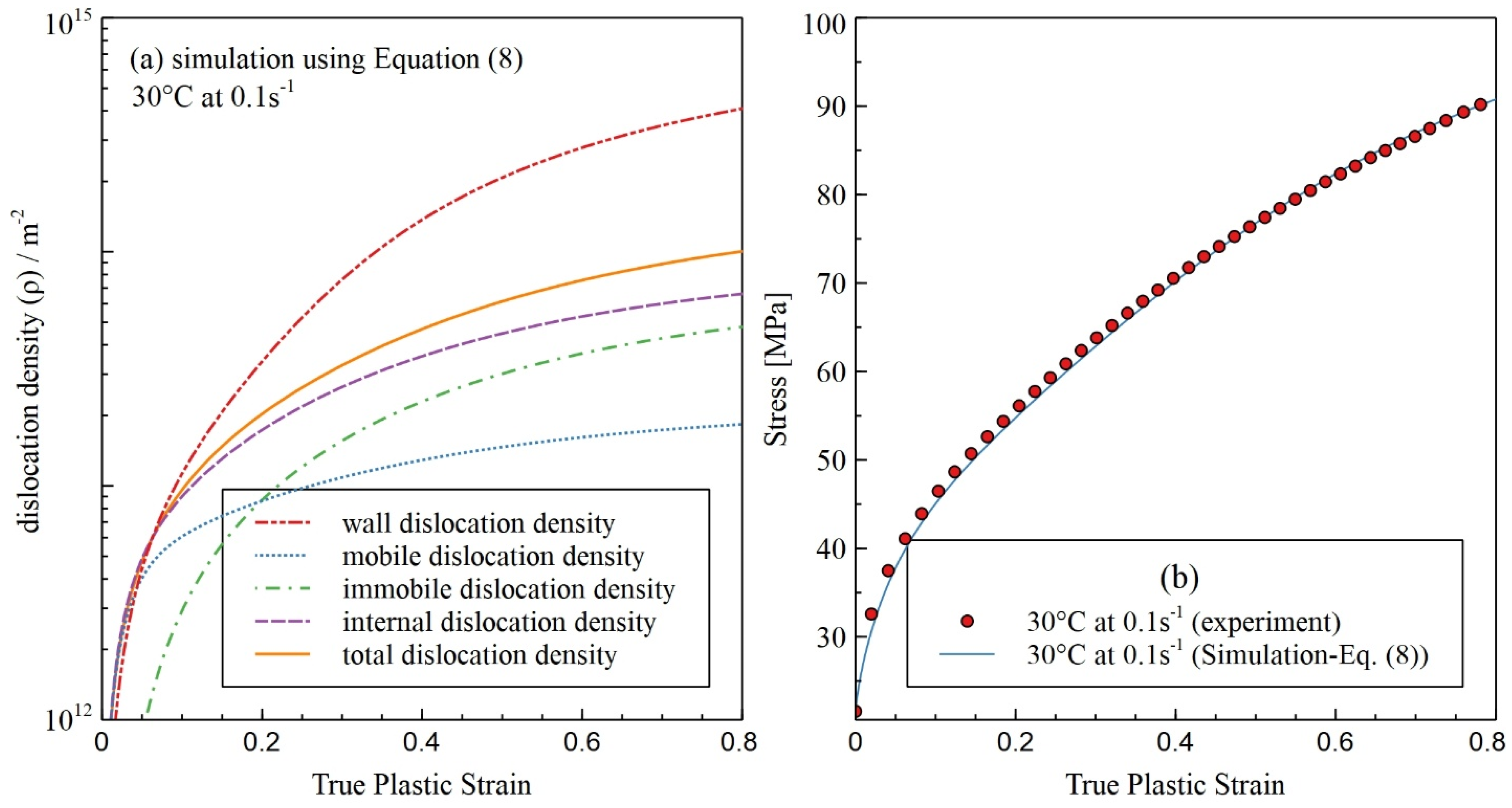

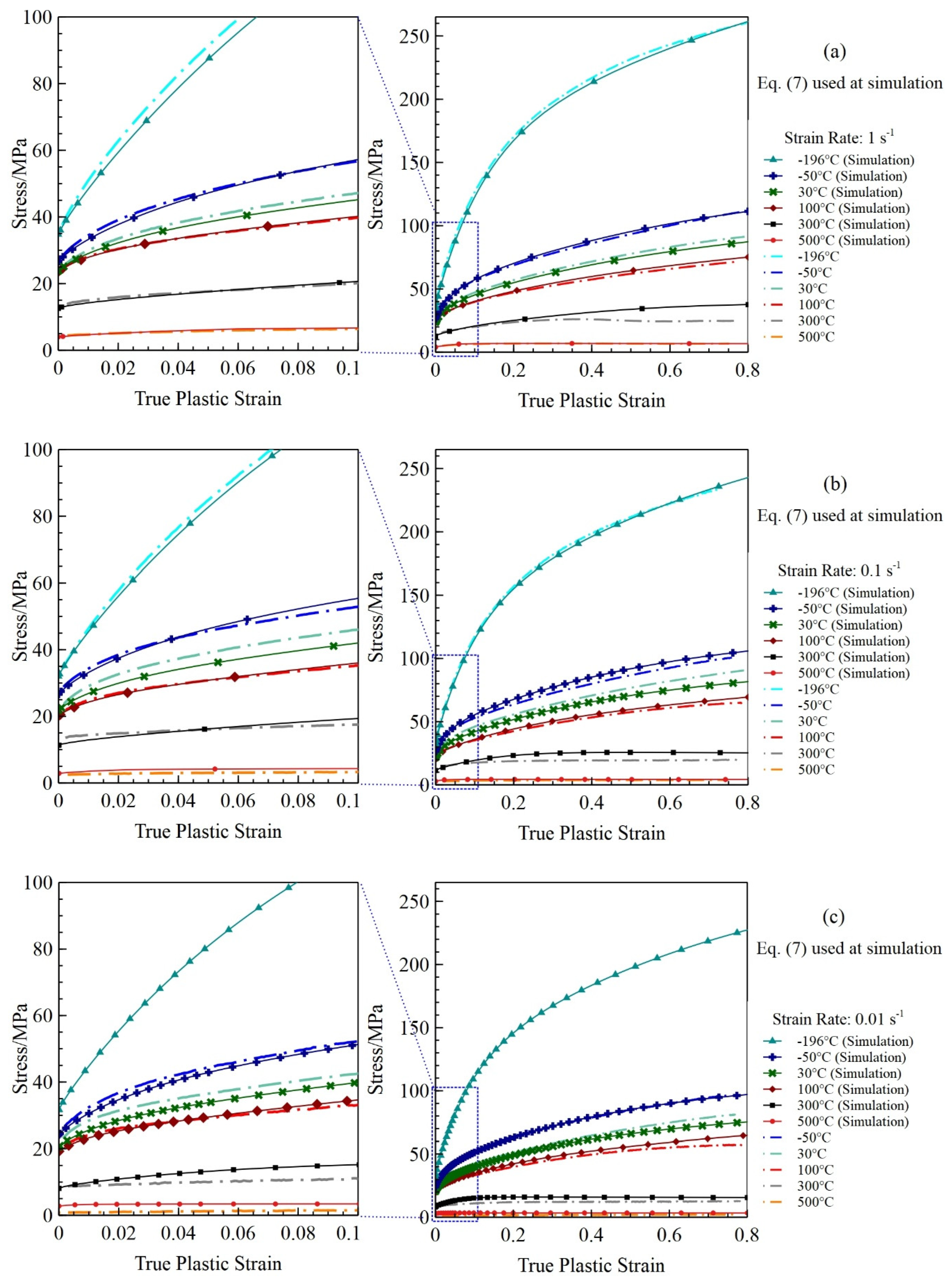

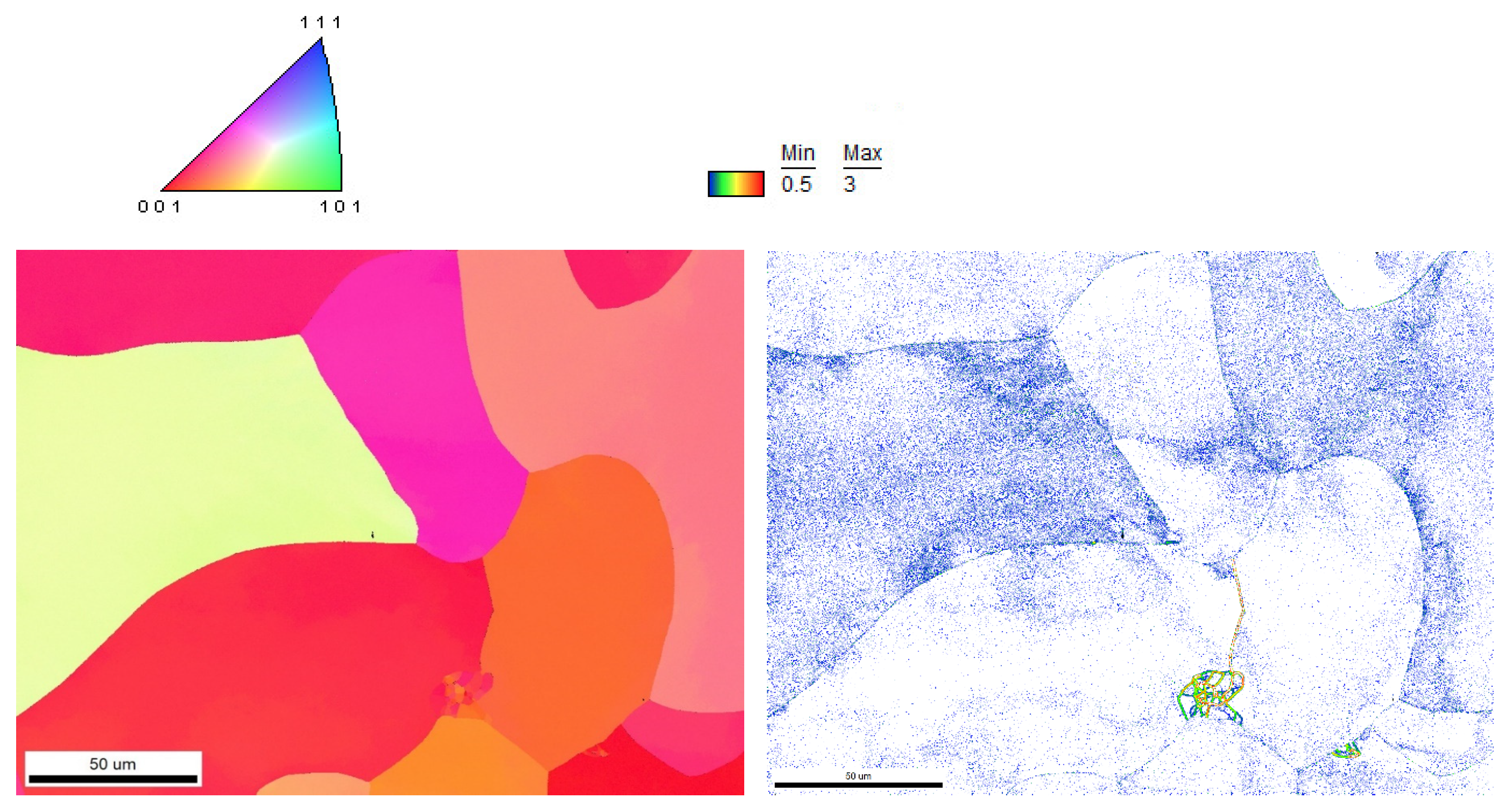

3. Results

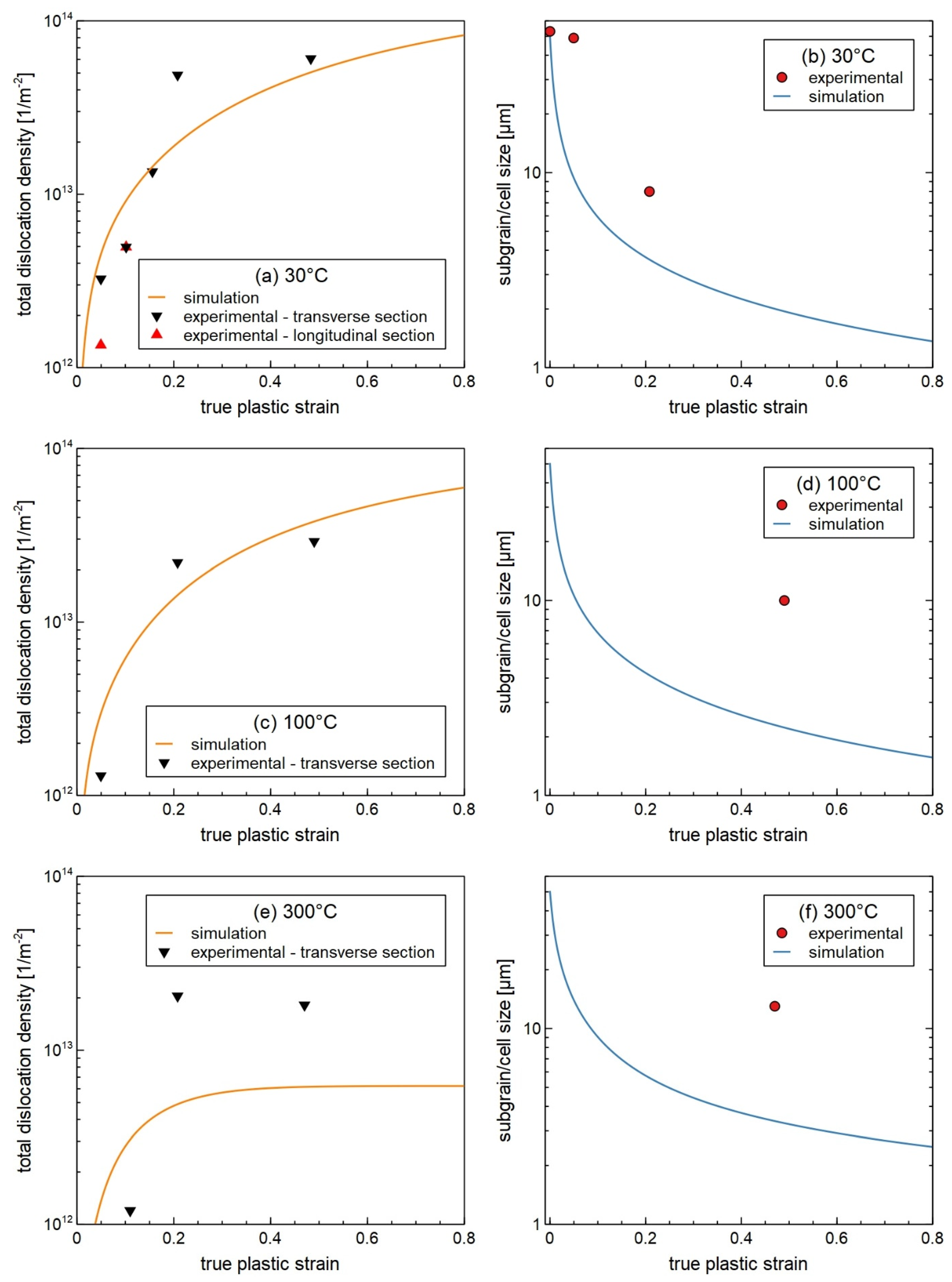

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Accurate stress–strain prediction: By incorporating temperature- and strain-rate-dependent dynamic annihilation terms, the model successfully reproduced the experimental flow curves across a wide range of strain rates and temperatures, capturing both work hardening and dynamic recovery behavior.

- (2)

- Flexible description of wall volume fraction: The new formulation can represent both increasing and decreasing trends in wall volume fraction reported in the literature, demonstrating the adaptability of the model to different microstructural evolution scenarios.

- (3)

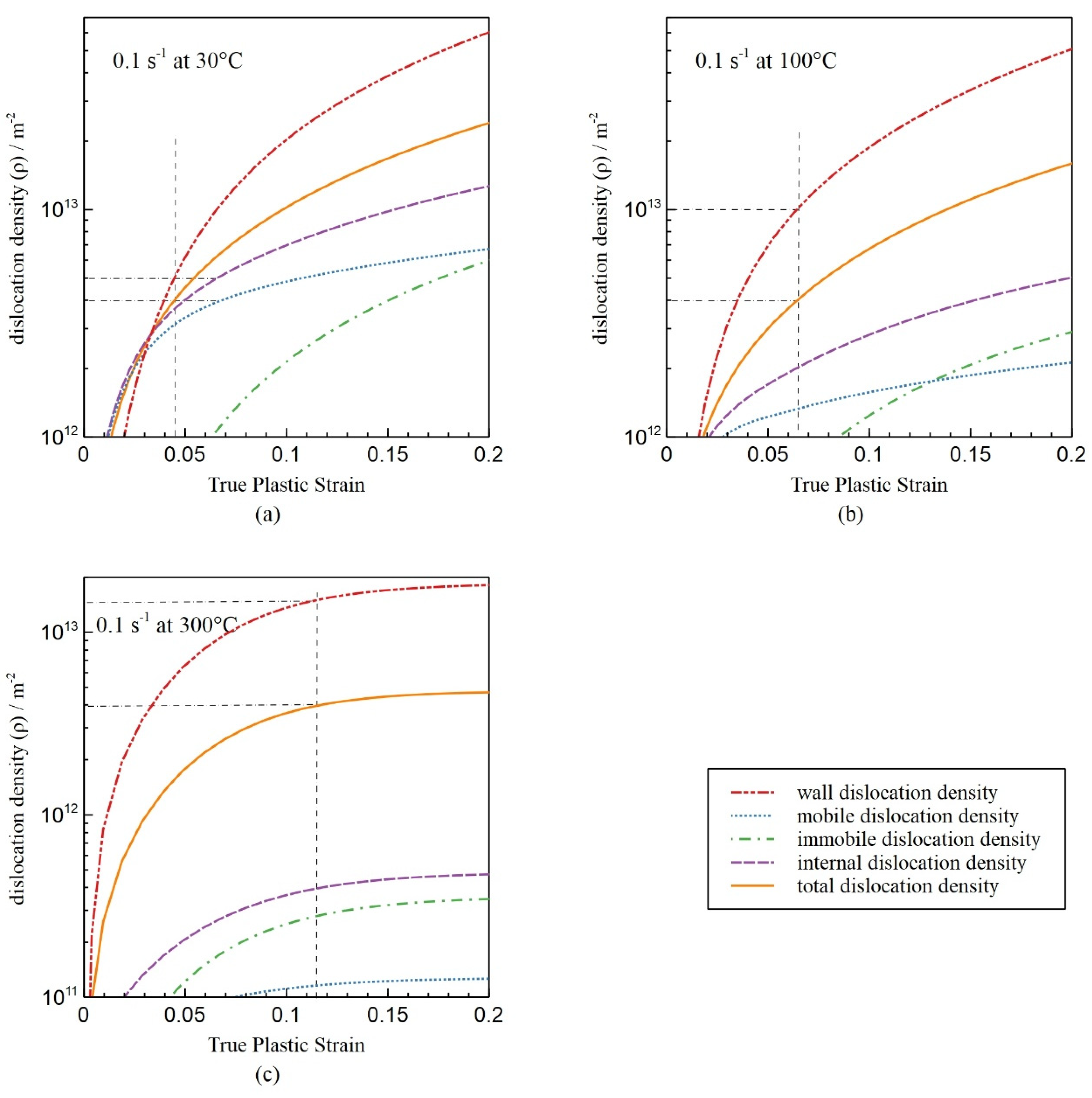

- Dislocation density evolution: The model accurately predicts the evolution of wall and cell dislocation densities, reflecting temperature effects on recovery and the transition toward steady-state deformation.

- (4)

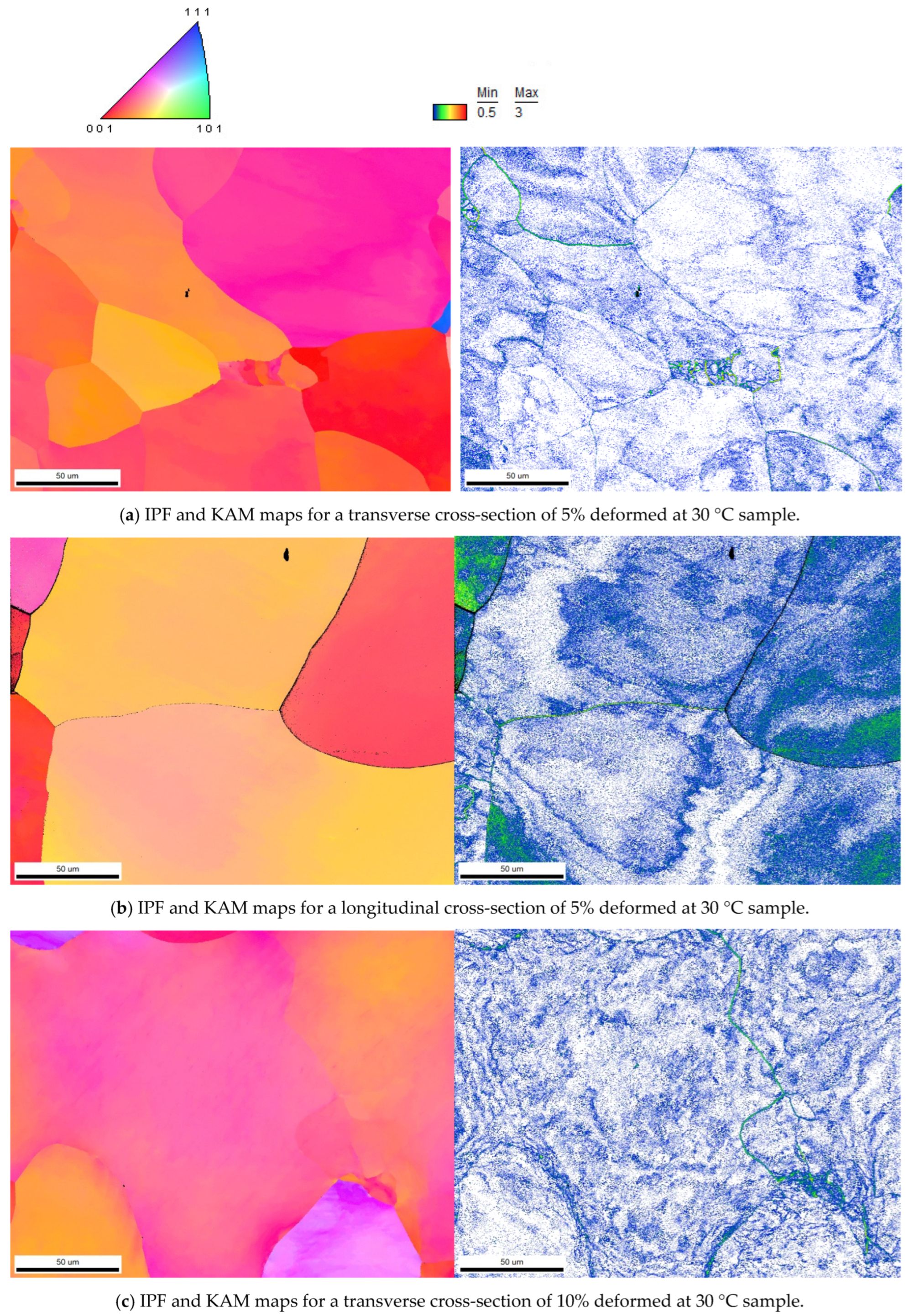

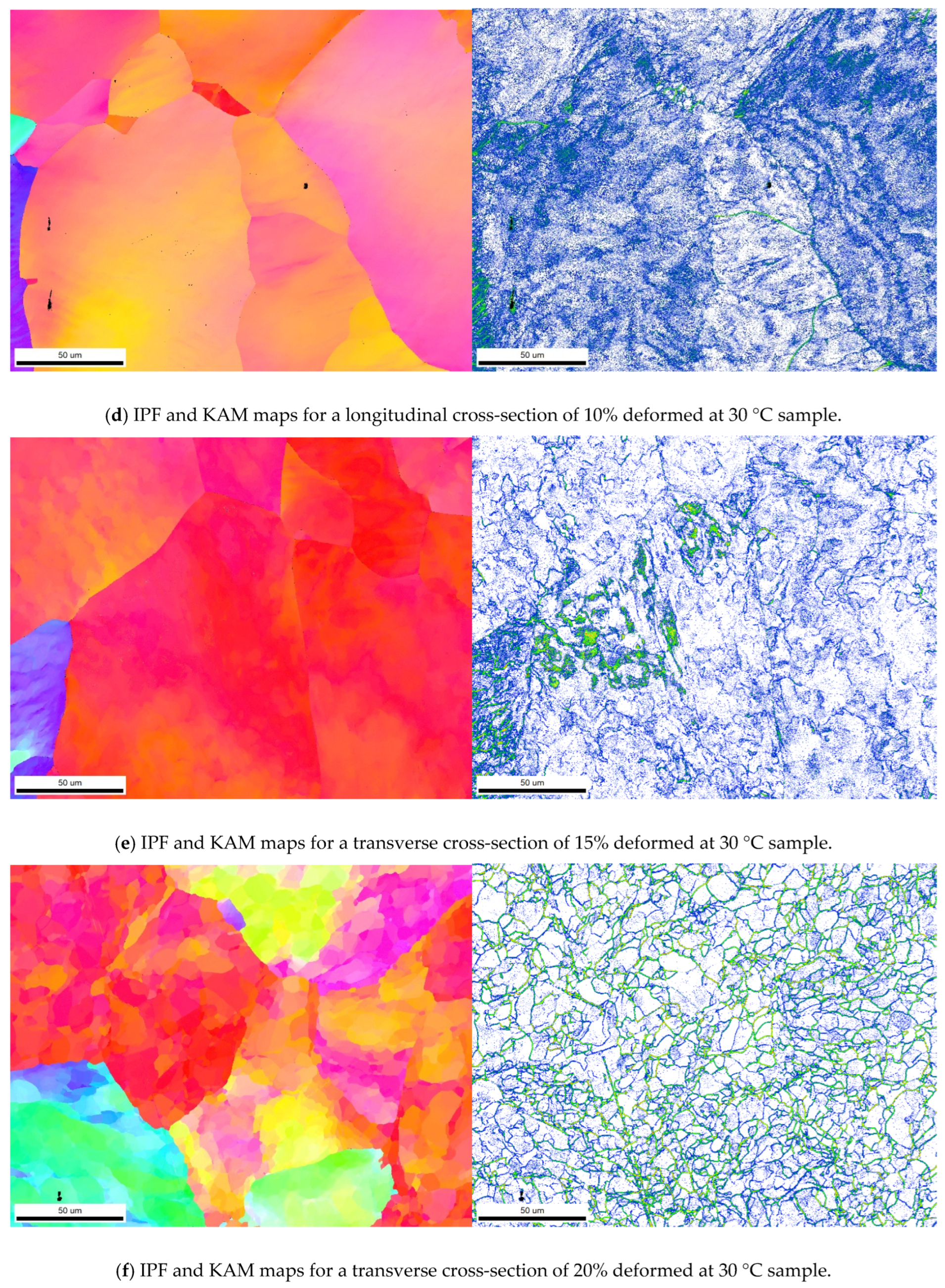

- Validation by EBSD measurements: EBSD analysis (GND, and subgrain/cell size) confirms the simulated microstructural trends, including reduced dislocation densities and larger subgrain sizes at higher temperatures, which are consistent with recovery-dominated deformation in ultra-pure aluminum.

- (5)

- Strong coherence between experiment and simulation: Overall, the extended model reproduces both the macroscopic mechanical response and the microscale dislocation-based mechanisms observed experimentally, demonstrating its capability to reliably describe the thermo-mechanical behavior of high-purity aluminum.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zerilli, F.J.; Armstrong, R.W. Dislocation-Mechanics-Based Constitutive Relations for Material Dynamics Calculations. J. Appl. Phys. 1987, 61, 1816–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roters, F.; Eisenlohr, P.; Hantcherli, L.; Tjahjanto, D.D.; Bieler, T.R.; Raabe, D. Overview of Constitutive Laws, Kinematics, Homogenization and Multiscale Methods in Crystal Plasticity Finite-Element Modeling: Theory, Experiments, Applications. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 1152–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaro, R.J.; Needleman, A. Texture Development and Strain Hardening in Rate Dependent Polycrystals. Acta Metall. 1985, 33, 923–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Ben Bettaieb, M.; Abed-Meraim, F.; Kalidindi, S.R. Computationally Efficient Predictions of Crystal Plasticity Based Forming Limit Diagrams Using a Spectral Database. Int. J. Plast. 2018, 103, 168–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Fuentes, J.C.; Rittel, D.; Osovski, S. On a Dislocation-Based Constitutive Model and Dynamic Thermomechanical Considerations. Int. J. Plast. 2018, 108, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkey, K.; Winther, G.; El-Azab, A. Theoretical Development of Continuum Dislocation Dynamics for Finite-Deformation Crystal Plasticity at the Mesoscale. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2020, 139, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhondzadeh, S.; Sills, R.B.; Bertin, N.; Cai, W. Dislocation Density-Based Plasticity Model from Massive Discrete Dislocation Dynamics Database. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2020, 145, 104152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabourot, L.; Fivel, M.; Rauch, E. Generalised Constitutive Laws for f.c.c. Single Crystals. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1997, 234–236, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocks, U.F. Laws for Work-Hardening and Low-Temperature Creep. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1976, 98, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, B.L.; Beyerlein, I.J.; Bronkhorst, C.A.; Cerreta, E.K.; Dennis-Koller, D. A Dislocation-Based Multi-Rate Single Crystal Plasticity Model. Int. J. Plast. 2013, 44, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Z.; Huang, M.X. A Dislocation-Based Flow Rule with Succinct Power-Law Form Suitable for Crystal Plasticity Finite Element Simulations. Int. J. Plast. 2021, 138, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenlis, A.; Parks, D.M. Modeling the Evolution of Crystallographic Dislocation Density in Crystal Plasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2002, 50, 1979–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerdeler, M.; Gottstein, G. A Microstructural Work Hardening Model Based on Three Internal State Variables. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 309–310, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocks, U.F.; Mecking, H. Physics and Phenomenology of Strain Hardening: The FCC Case. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2003, 48, 171–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchi, E.S. Constitutive Equations for Commercial-Purity Aluminum Deformed under Hot-Working Conditions. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. Trans. ASME 1995, 117, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Elkhier, M. Modeling of High-Temperature Deformation of Commercial Pure Aluminum (1050). J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2004, 13, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, Y.; Kubin, L.P. Local Strain Hardening and Nonuniformity of Plastic Deformation. Acta Metall. 1986, 34, 2455–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, L.P.; Estrin, Y. Evolution of Dislocation Densities and the Critical Conditions for the Portevin-Le Châtelier Effect. Acta Metall. Mater. 1990, 38, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlat, F.; Glazov, M.V.; Brem, J.C.; Lege, D.J. A Simple Model for Dislocation Behavior, Strain and Strain Rate Hardening Evolution in Deforming Aluminum Alloys. Int. J. Plast. 2002, 18, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, D.; Bacon, D.J. Introduction to Dislocations, 5th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 9780080966724. [Google Scholar]

- Bammann, D.J. An Internal Variable Model of Viscoplasticity. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1984, 22, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Kozeschnik, E. Modeling the Evolution of the Dislocation Density and Yield Stress of Al over a Wide Range of Temperatures and Strain Rates. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2024, 55, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, Y.; Tóth, L.S.; Molinari, A.; Bréchet, Y. A Dislocation-Based Model for All Hardening Stages in Large Strain Deformation. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 5509–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelluccio, G.M.; McDowell, D.L. Mesoscale Cyclic Crystal Plasticity with Dislocation Substructures. Int. J. Plast. 2017, 98, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.S.; Holdsworth, S.R. Evolution of Relationships between Dislocation Microstructures and Internal Stresses of AISI 316L during Cyclic Loading at 293 K and 573 K (20 °C and 300 °C). Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2014, 45, 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, C.; Bernacki, M.; Besnard, R.; Bozzolo, N. About Quantitative EBSD Analysis of Deformation and Recovery Substructures in Pure Tantalum. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 89, 012038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, F.J. Grain and Subgrain Characterisation by Electron Backscatter Diffraction. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 3833–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, D.; Kamikawa, N.; Tsuji, N. High Pressure Torsion to Refine Grains in Pure Aluminum up to Saturation: Mechanisms of Structure Evolution and Their Dependence on Strain. Philos. Mag. 2012, 92, 2329–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitbarth, E.; Zaefferer, S.; Archie, F.; Besel, M.; Raabe, D.; Requena, G. Evolution of Dislocation Patterns inside the Plastic Zone Introduced by Fatigue in an Aged Aluminium Alloy AA2024-T3. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 718, 345–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J. Some Geometrical Relations in Dislocated Crystals. Acta Metall. 1953, 1, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilby, B.A.; Bullough, R.; Smith, E. Continuous Distributions of Dislocations: A New Application of the Methods of Non-Riemannian Geometry. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1955, 231, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröner, E. Allgemeine Kontinuumstheorie Der Versetzungen Und Eigenspannungen. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 1959, 4, 273–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, W.; Wan, J.; Misra, R.D.K.; Wang, Q.; Wang, C. The Grain Size and Orientation Dependence of Geometrically Necessary Dislocations in Polycrystalline Aluminum during Monotonic Deformation: Relationship to Mechanical Behavior. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 775, 138939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F. The Deformation of Plastically Non-Homogeneous Materials. Philos. Mag. 1970, 21, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, D.P.; Trivedi, P.B.; Wright, S.I.; Kumar, M. Analysis of Local Orientation Gradients in Deformed Single Crystals. Ultramicroscopy 2005, 103, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Adams, B.L.; King, W.E. Observations of Lattice Curvature near the Interface of a Deformed Aluminium Bicrystal. Philos. Mag. A Phys. Condens. Matter Struct. Defects Mech. Prop. 2000, 80, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, C.F.O.; Saito, Y.; Öztop, M.S.; Kysar, J.W. Geometrically Necessary Dislocation Density Measurements at a Grain Boundary Due to Wedge Indentation into an Aluminum Bicrystal. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2017, 105, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Tao, N.R.; Lu, K. Effects of Impurity on Microstructure and Hardness in Pure Al Subjected to Dynamic Plastic Deformation at Cryogenic Temperature. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2011, 27, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Ma, W.; Pantleon, W. Microstructure of Individual Grains in Cold-Rolled Aluminium from Orientation Inhomogeneities Resolved by Electron Backscattering Diffraction. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 494, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrominski, W.; Lewandowska, M. Mechanisms of Plastic Deformation in Ultrafine-Grained Aluminium—In-Situ and Ex-Post Studies. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 715, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjewar, H.; Naghdy, S.; Verleysen, P.; Kestens, L.A.I. Statistical Analysis of Dislocation Substructure in Commercially Pure Aluminum Subjected to Static and Dynamic High Pressure Torsion. Mater. Charact. 2020, 160, 110088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaya, M. Assessment of Local Deformation Using EBSD: Quantification of Accuracy of Measurement and Definition of Local Gradient. Ultramicroscopy 2011, 111, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konijnenberg, P.J.; Zaefferer, S.; Raabe, D. Assessment of Geometrically Necessary Dislocation Levels Derived by 3D EBSD. Acta Mater. 2015, 99, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyed Salehi, M.; Anjabin, N.; Kim, H.S. Study of Geometrically Necessary Dislocations of a Partially Recrystallized Aluminum Alloy Using 2D EBSD. Microsc. Microanal. 2019, 25, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.T.; Jackson, B.E.; Fullwood, D.T.; Wright, S.I.; De Graef, M.; Homer, E.R.; Wagoner, R.H. Influence of Noise-Generating Factors on Cross-Correlation Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) Measurement of Geometrically Necessary Dislocations (GNDs). Microsc. Microanal. 2017, 23, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghdy, S.; Verleysen, P.; Petrov, R.; Kestens, L. Resolving the Geometrically Necessary Dislocation Content in Severely Deformed Aluminum by Transmission Kikuchi Diffraction. Mater. Charact. 2018, 140, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreyca, J.; Kozeschnik, E. State Parameter-Based Constitutive Modelling of Stress Strain Curves in Al-Mg Solid Solutions. Int. J. Plast. 2018, 103, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G.I. The Mechanism of Plastic Deformation of Crystals. Part I.—Theoretical. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Character 1934, 145, 362–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orowan, E. Zur Kristallplastizität. I—Tieftemperaturplastizität und Beckersche Formel. Zeitschrift für Phys. 1934, 89, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roters, F.; Raabe, D.; Gottstein, G. Work Hardening in Heterogeneous Alloys—A Microstructural Approach Based on Three Internal State Variables. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 4181–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, J. Discolations, 1st ed.; Pergamon Press Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F.D.; Svoboda, J.; Appel, F.; Kozeschnik, E. Modeling of Excess Vacancy Annihilation at Different Types of Sinks. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 3463–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, G.V.S.S.; Goerdeler, M.; Gottstein, G. Work Hardening Model Based on Multiple Dislocation Densities. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 400–401, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagneborg, R.; Zajac, S.; Hutchinson, B. A Model for the Flow Stress Behaviour during Hot Working of Aluminium Alloys Containing Non-Deformable Precipitates. Scr. Metall. Mater. 1993, 29, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, L.E.; Domkin, K.; Hansson, S. Dislocations, Vacancies and Solute Diffusion in Physical Based Plasticity Model for AISI 316L. Mech. Mater. 2008, 40, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Zehetbauer, M.; Borbely, A.; Ungar, T. Dislocation Density and Long Range Internal Stresses in Heavily Cold Worked Cu Measured by X-Ray Line Broadening. Int. J. Mater. Res. 1995, 86, 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughrabi, H.; Ungár, T.; Kienle, W.; Wilkens, M. Long-Range Internal Stresses and Asymmetric X-Ray Line-Broadening in Tensile-Deformed [001]-Orientated Copper Single Crystals. Philos. Mag. A 1986, 53, 793–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Y.; Horita, Z. Microstructural Evolution in Pure Aluminum Processed by High-Pressure Torsion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 503, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindarlou, S.; Castelluccio, G.M. Substructure-Sensitive Crystal Plasticity with Material-Invariant Parameters. Int. J. Plast. 2022, 155, 103306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, P.W.J.; Lapovok, R.; Estrin, Y. The Influence of Back Pressure on ECAP Processed AA 6016: Modeling and Experiment. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 2985–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.C.; Estrin, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Hellmig, R.J. Dislocation Density-Based Modeling of Deformation Behavior of Aluminium under Equal Channel Angular Pressing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 351, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, F.; Castelluccio, G.M. On the Similitude Relation for Dislocation Wall Thickness under Cyclic Deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 840, 142972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozeschnik, E. Mean-Field Microstructure Kinetics Modeling. Encycl. Mater. Met. Alloys 2022, 4, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauzay, M.; Kubin, L.P. Scaling Laws for Dislocation Microstructures in Monotonic and Cyclic Deformation of Fcc Metals. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2011, 56, 725–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M. Introduction to the Theory of Dislocations; Shokabo: Tokyo, Japan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bergström, Y. The Plastic Deformation of Metals—A Dislocation Model and Its Applicability. Rev. Powder Metall. Phys. Ceram. 1983, 2, 79–265. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Nava, E.I.; Sietsma, J.; Rivera-Díaz-Del-Castillo, P.E.J. Dislocation Annihilation in Plastic Deformation: II. Kocks-Mecking Analysis. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 2615–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecking, H.; Nicklas, B.; Zarubova, N.; Kocks, U.F. A “Universal” Temperature Scale for Plastic Flow. Acta Metall. 1986, 34, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, E. Modelling of Work Hardening and Stress Saturation in FCC Metals. Prog. Mater. Sci. 1997, 41, 129–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H.J.; Ashby, M.F. Deformation-Mechanism Maps: The Plasticity and Creep of Metals and Ceramics, 1st ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1981; ISBN 0080293387. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Li, F.-G.; Cao, J.; Ma, X.-K.; Li, J.-H. Constitutive Equations of 1060 Pure Aluminum Based on Modified Double Multiple Nonlinear Regression Model. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Juul Jensen, D.; Hansen, N. Effect of Grain Orientation on Deformation Structure in Cold-Rolled Polycrystalline Aluminium. Acta Mater. 1998, 46, 5819–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, P.; Pál, G.; Sidor, J.J. The Dependency of Work Hardening on Dislocation Statistics in Cold Rolled 1050 Aluminum Alloy. Mater. Charact. 2022, 191, 112166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wojcik, T.; Kozeschnik, E. Subgrain Size Modeling and Substructure Evolution in an AA1050 Aluminum Alloy during High-Temperature Compression. Materials 2024, 17, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkholt, S.; Nes, E.; Marthinsen, K. Orientation Independent and Dependent Subgrain Growth during Iso-Thermal Annealing of High- Purity and Commercial Purity Aluminium. Metals 2019, 9, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Humphreys, F.J. Subgrain Growth and Low Angle Boundary Mobility in Aluminium Crystals of Orientation {110} <001>. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 2017–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.X.; Lin, J.L.; Chang, C.P.; Kao, P.W. Microstructural Characterization of Warm-Worked Commercially Pure Aluminum. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2006, 37, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.M.; Ding, S.X.; Chang, C.P.; Kao, P.W. Plane Strain Deformation Microstructure of Warm-Worked Aluminum. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 512, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temp. | True Strain | Investigated Plane |

|---|---|---|

| 30 °C | 0.05 | transverse and longitudinal |

| 30 °C | 0.1 | transverse and longitudinal |

| 30 °C | 0.16 | transverse |

| 30 °C | 0.21 | transverse |

| 30 °C | 0.48 | transverse |

| 100 °C | 0.05 | transverse |

| 100 °C | 0.21 | transverse |

| 100 °C | 0.49 | transverse |

| 300 °C | 0.11 | transverse |

| 300 °C | 0.21 | transverse |

| 300 °C | 0.47 | transverse |

| Functions Based on Equation (7) | Functions Based on Equation (8) |

|---|---|

| Average of the KAM Related | As-Received Sample | True Strain 0.05 | True Strain 0.1 | True Strain 0.16 | True Strain 0.21 | True Strain 0.48 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st nearest neighbors | 0.4390 | 0.5450 | 0.4050 | 0.4440 | 0.5020 | 0.4140 |

| 2nd nearest neighbors | 0.4420 | 0.5480 | 0.4100 | 0.4500 | 0.5080 | 0.4310 |

| 3rd nearest neighbors | 0.4450 | 0.5500 | 0.4150 | 0.4580 | 0.5160 | 0.4540 |

| 4th nearest neighbors | 0.4480 | 0.5520 | 0.4210 | 0.4670 | 0.5250 | 0.4780 |

| 5th nearest neighbors | 0.4500 | 0.5540 | 0.4260 | 0.4760 | 0.5340 | 0.5010 |

| Gave | 0.0028 | 0.0022 | 0.0053 | 0.0081 | 0.0081 | 0.0221 |

| Temp. | True Strain | Measured Dislocation Densities [1013/m2] | Simulated Total Dislocation Densities by MatCalc [1013/m2] | Measured Subgrain/Cell Size [µm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-received | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 53 |

| 30 °C | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 49 |

| 30 °C-longitudinal | 0.05 | 0.32 | 0.47 | - |

| 30 °C | 0.1 | 0.50 | 1.02 | - |

| 30 °C-longitudinal | 0.1 | 0.50 | 1.02 | - |

| 30 °C | 0.16 | 1.35 | 1.70 | - |

| 30 °C | 0.21 | 4.87 | 2.12 | 8 |

| 30 °C | 0.48 | 6.06 | 5.35 | - |

| 100 °C | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.31 | - |

| 100 °C | 0.21 | 2.20 | 1.58 | - |

| 100 °C | 0.49 | 2.91 | 4.31 | 10 |

| 300 °C | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.4 | - |

| 300 °C | 0.21 | 2.05 | 0.63 | - |

| 300 °C | 0.47 | 1.82 | 0.80 | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadeghi, A.; Kahlenberg, R.; Wojcik, T.; Schuster, R.; Retzl, P.; Shan, Y.V.; Kozeschnik, E. Modeling and Experimental Analysis of the Dislocation Structure Evolution During Deformation of High-Purity Aluminum. Metals 2025, 15, 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121348

Sadeghi A, Kahlenberg R, Wojcik T, Schuster R, Retzl P, Shan YV, Kozeschnik E. Modeling and Experimental Analysis of the Dislocation Structure Evolution During Deformation of High-Purity Aluminum. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121348

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadeghi, Abbas, Robert Kahlenberg, Tomasz Wojcik, Roman Schuster, Philipp Retzl, Yao V. Shan, and Ernst Kozeschnik. 2025. "Modeling and Experimental Analysis of the Dislocation Structure Evolution During Deformation of High-Purity Aluminum" Metals 15, no. 12: 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121348

APA StyleSadeghi, A., Kahlenberg, R., Wojcik, T., Schuster, R., Retzl, P., Shan, Y. V., & Kozeschnik, E. (2025). Modeling and Experimental Analysis of the Dislocation Structure Evolution During Deformation of High-Purity Aluminum. Metals, 15(12), 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121348