Effect of Nickel Impurities in Pyrite on Catalytic Degradation of Thiosulfate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Test Methods

2.2.1. Synthesis of Pure-Phase Pyrite

2.2.2. Synthesis of Nickel-Bearing Pyrite

2.2.3. Photocatalytic Degradation Experiment

2.2.4. Leaching Experiment and Detection Method

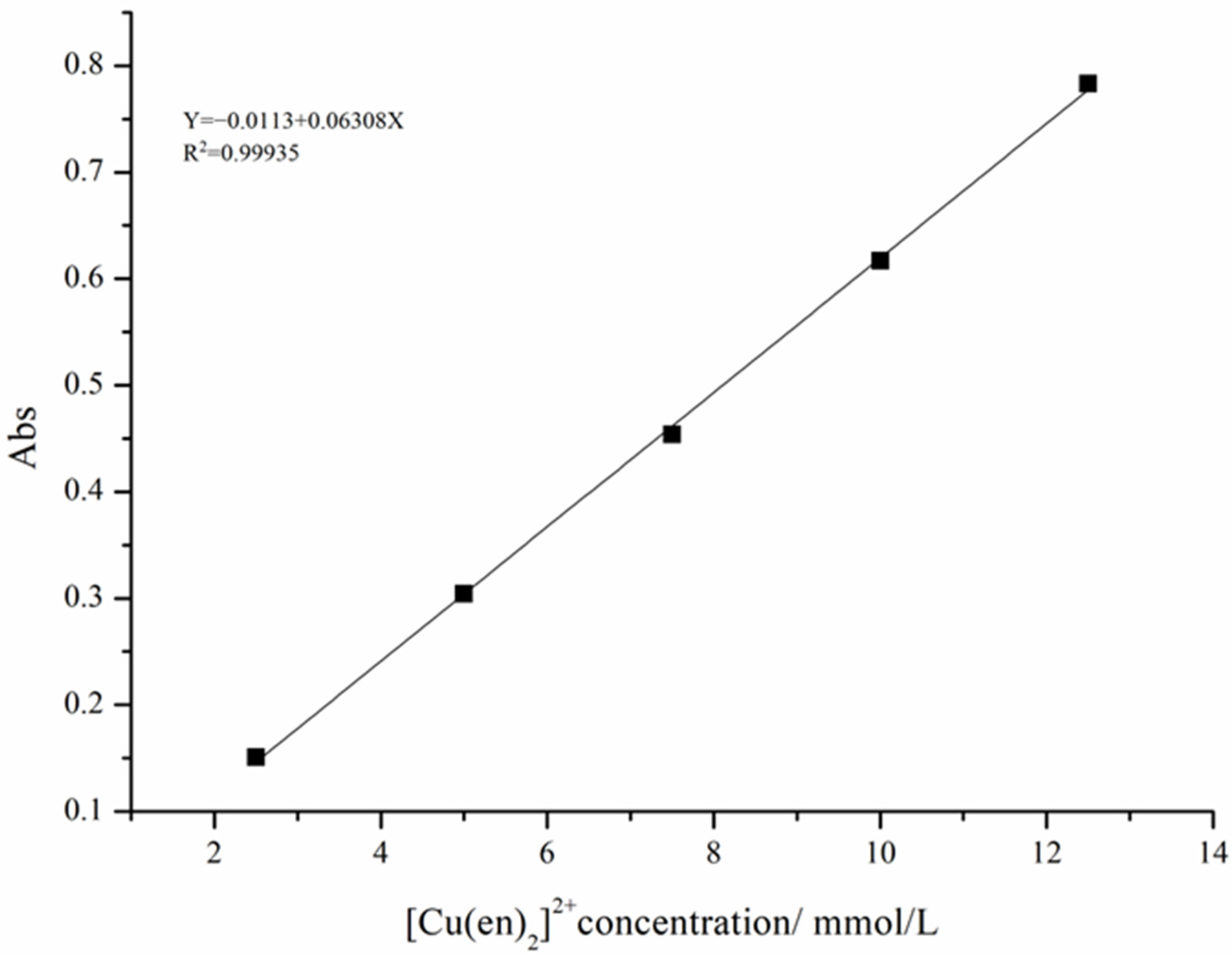

2.2.5. Determination of the Cu(en)22+ Complex Concentration

| Intercept | Slope | Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Standard Error | Value | Standard Error | Adj. R-Square | |

| C | −0.0113 | 0.00669 | 0.06308 | 8.06308 × 10−4 | 0.99935 |

2.3. Sample Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

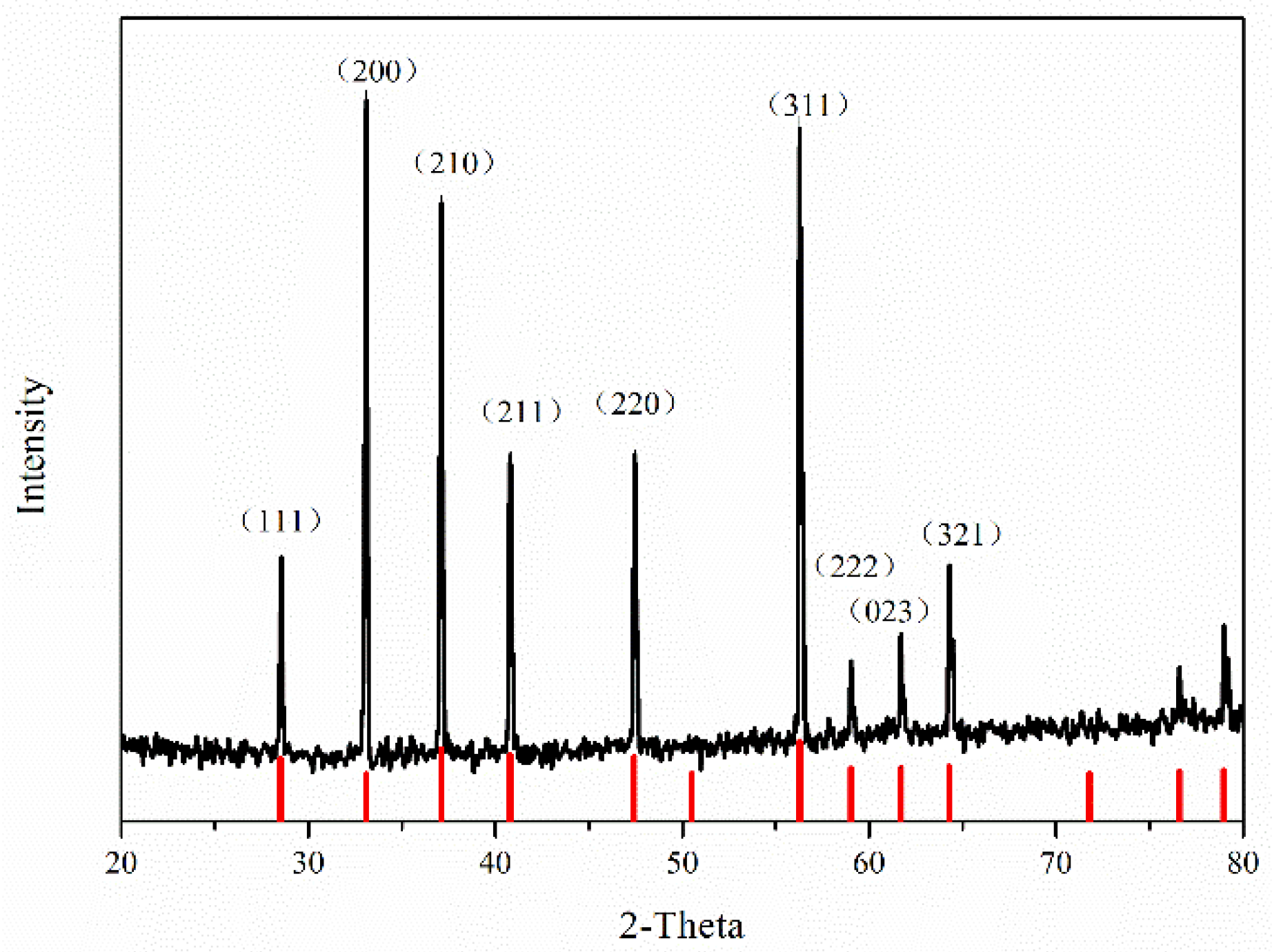

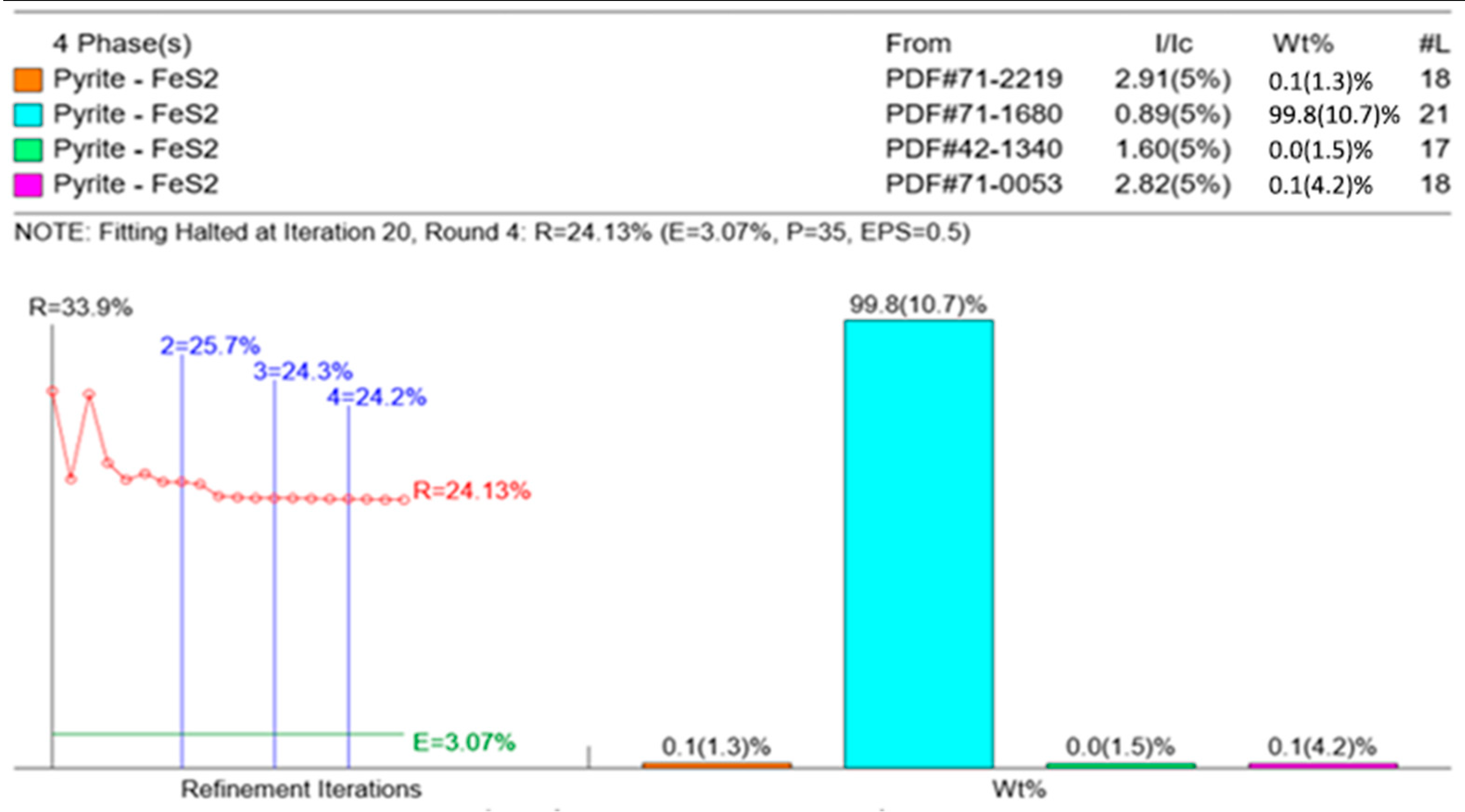

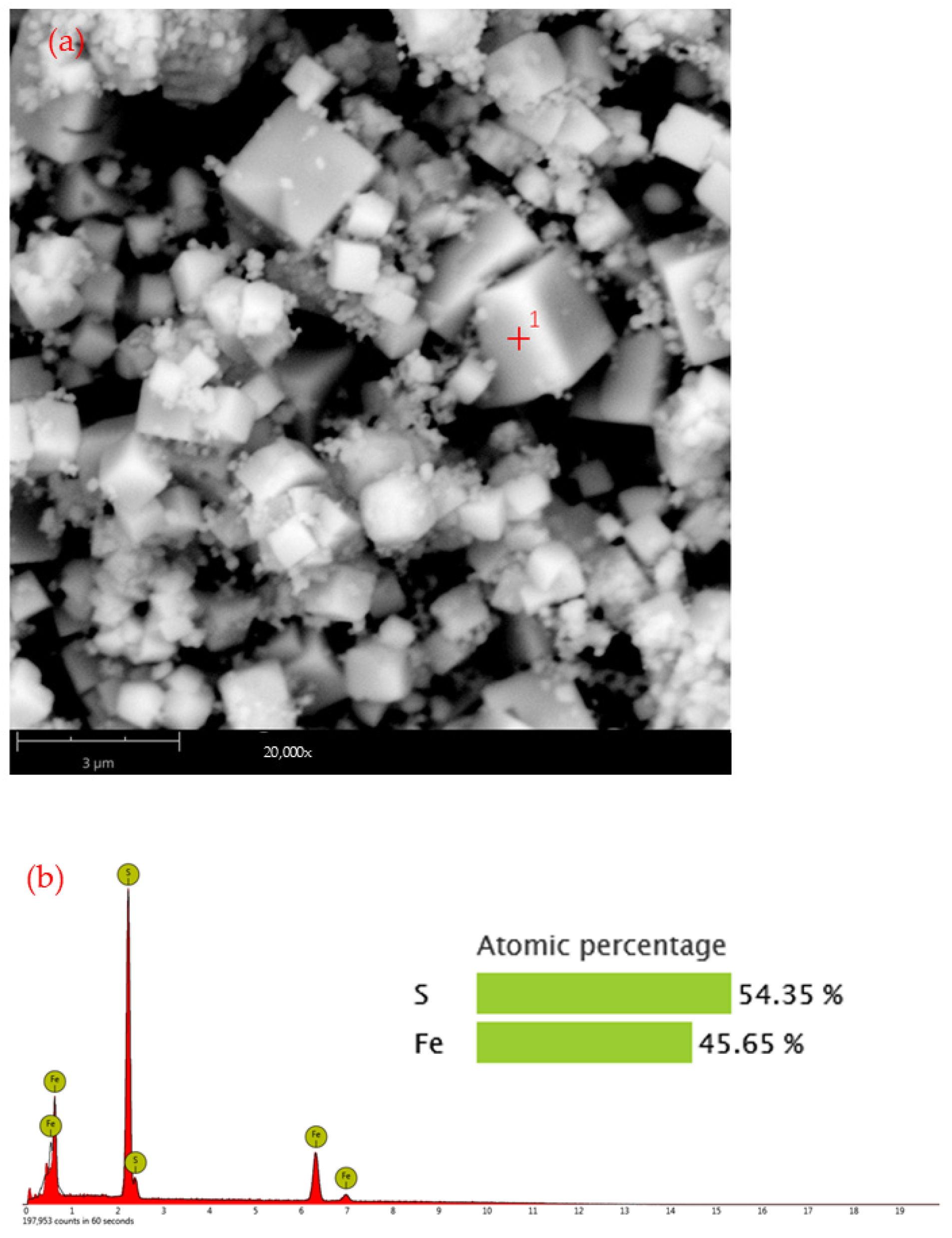

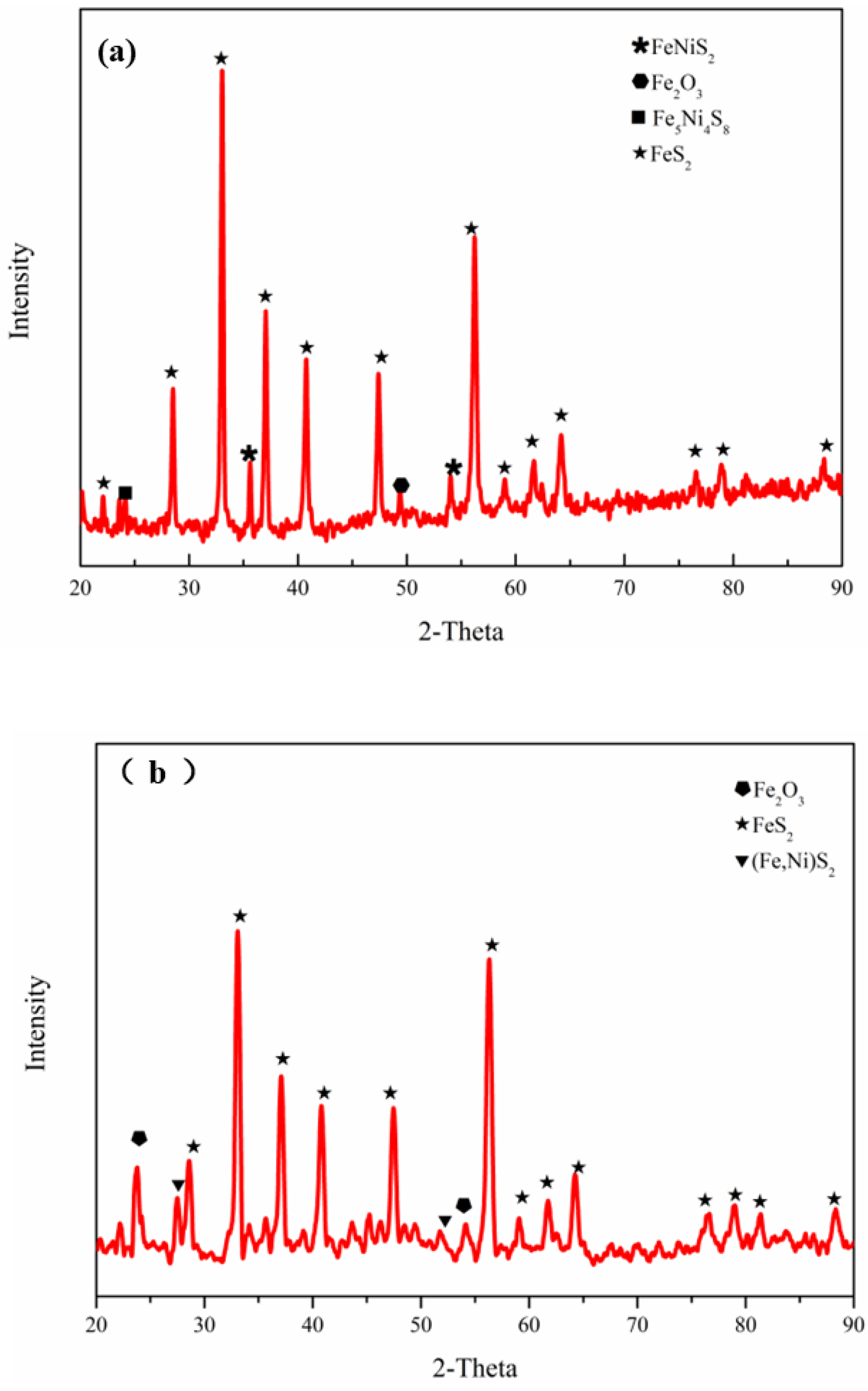

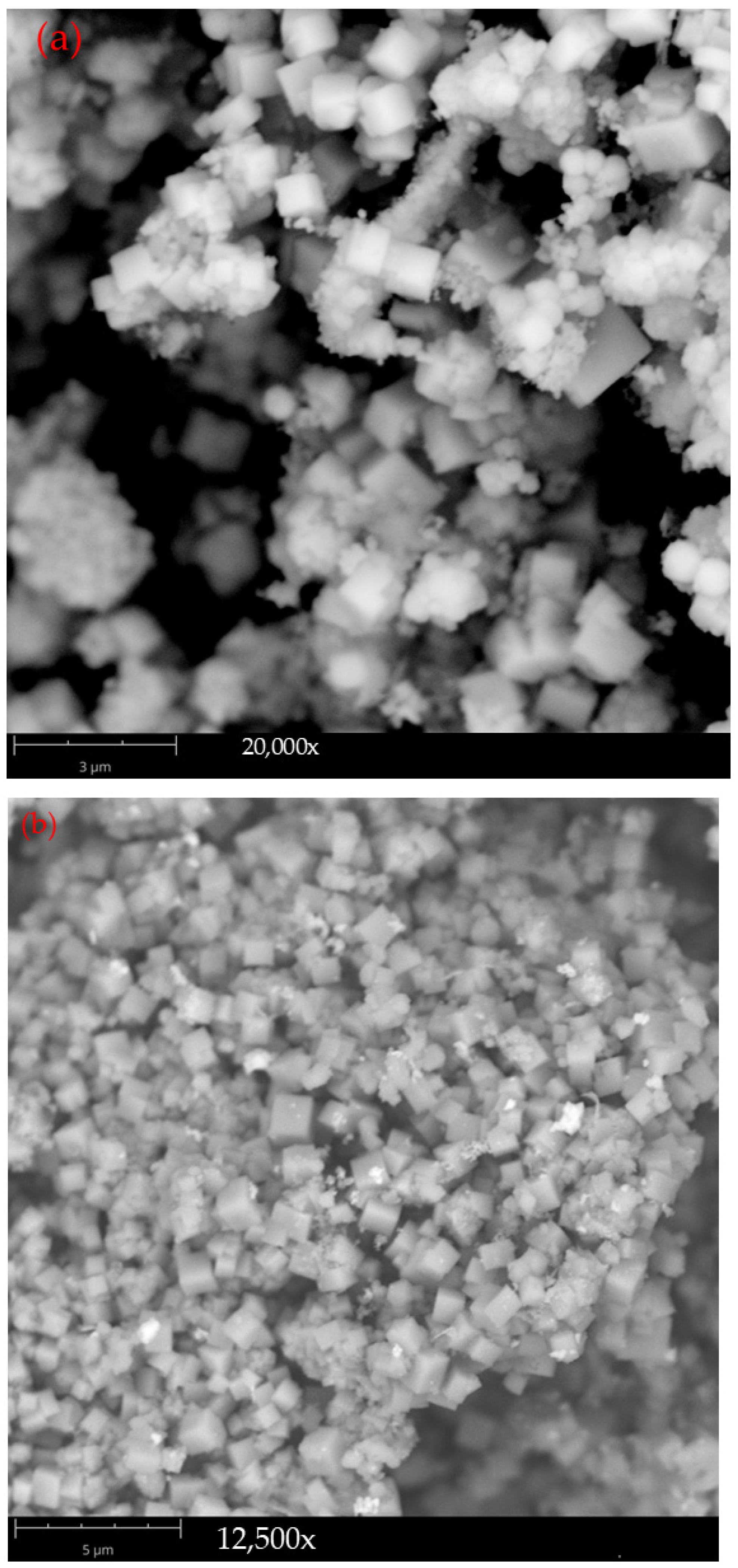

3.1. Phase and Morphology of Synthesized Pure-Phase Pyrite

3.2. Influence of the Nickel Doping Content on the Properties of Pyrite

3.2.1. Phase and Morphology of Nickel-Bearing Pyrite

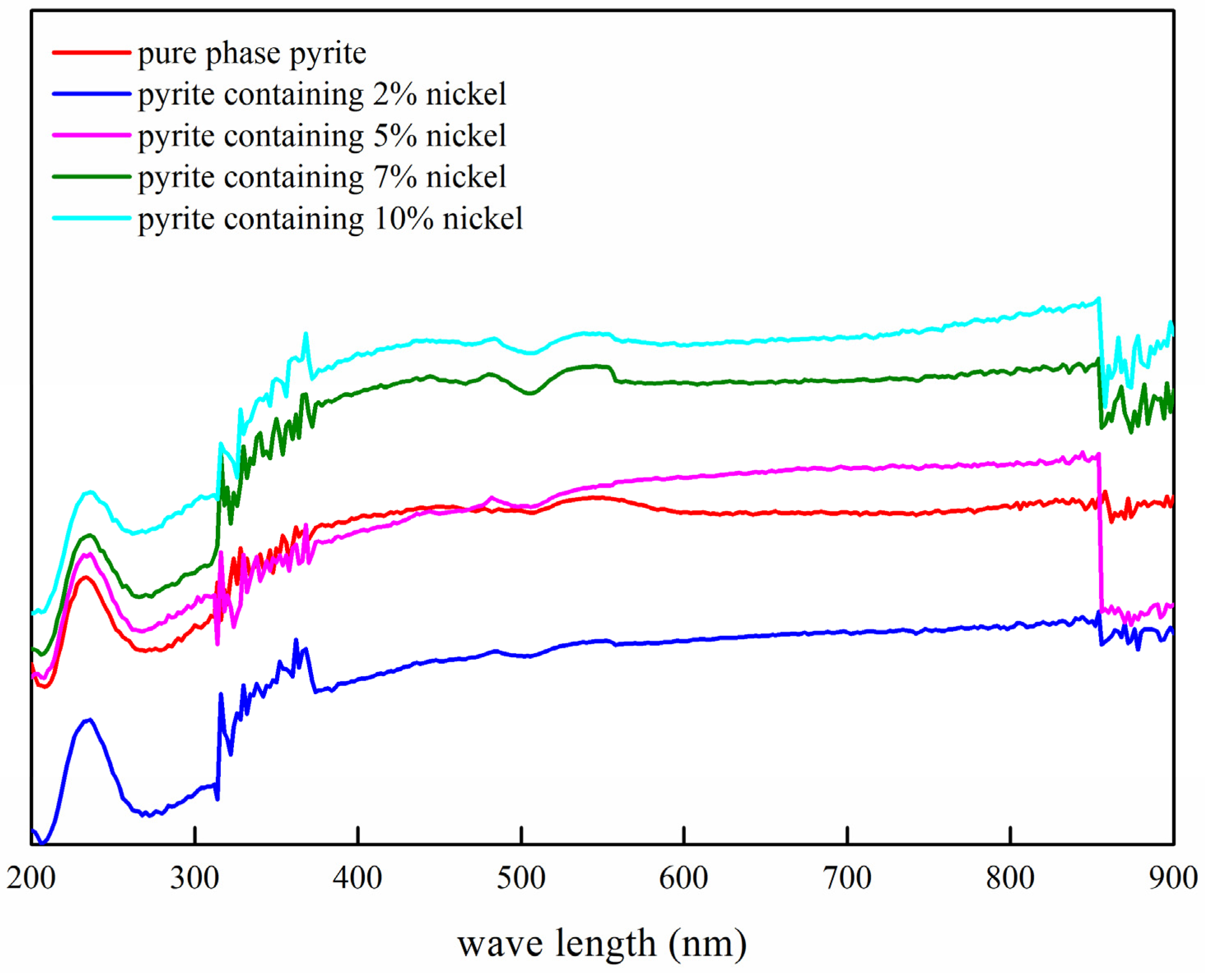

3.2.2. Influence of the Nickel Doping Amount on the Semiconductor Properties of Synthetic Products

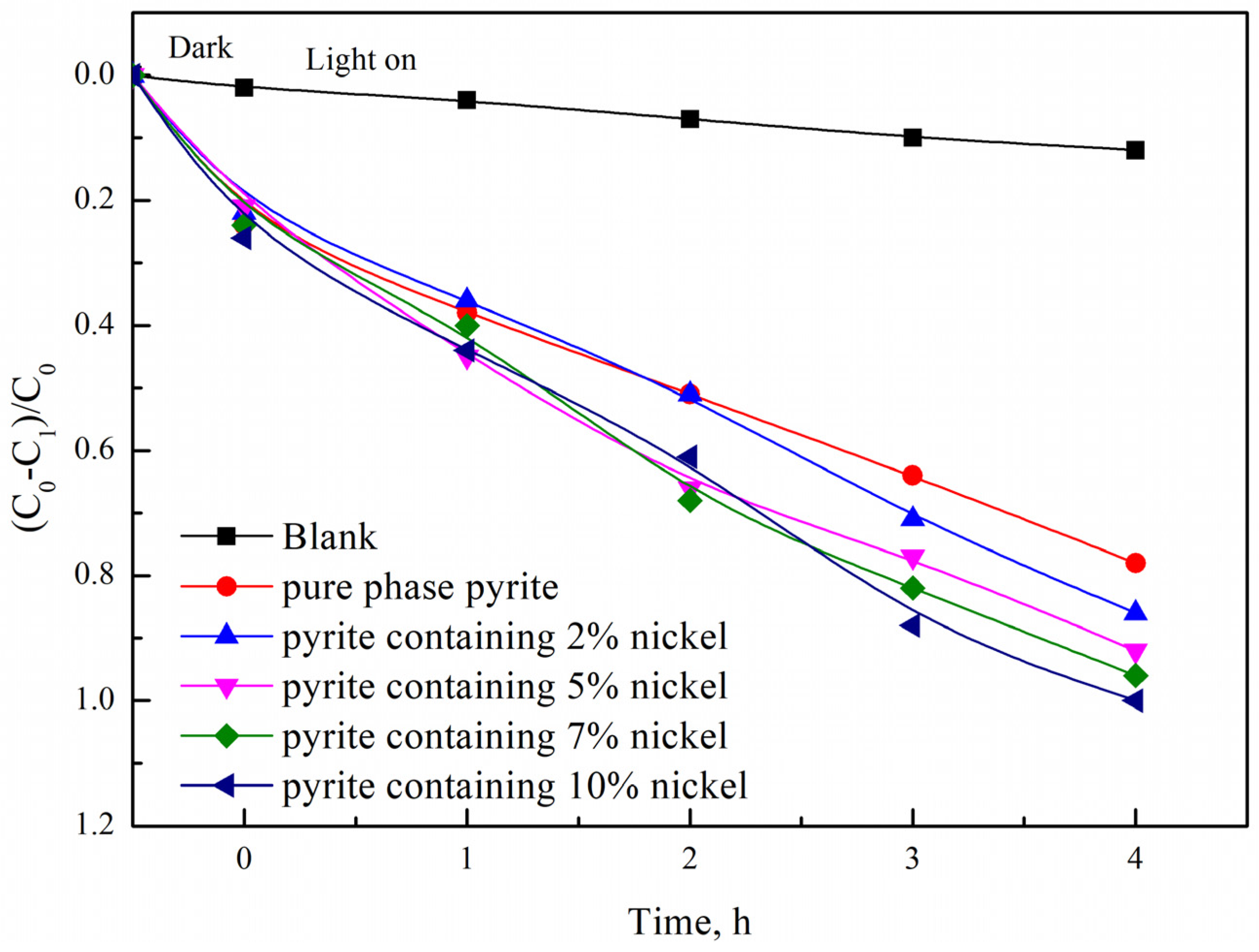

3.2.3. Influence of the Nickel Doping Amount on the Photocatalytic Degradation Properties of Synthetic Products

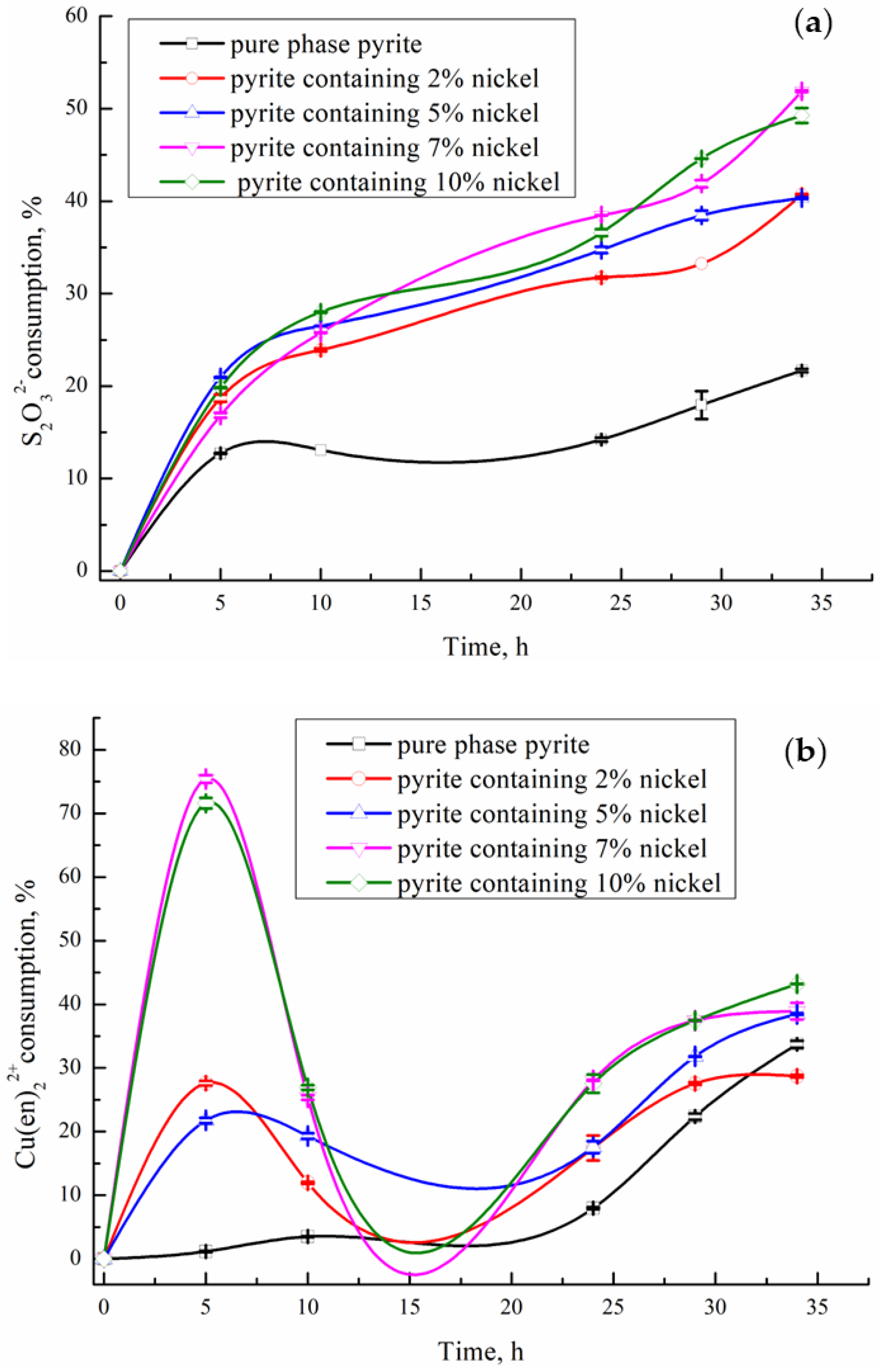

3.3. Influence of Nickel-Containing Pyrite on the Consumption of Thiosulfate and Cu(en)22+ in the System

3.4. Mechanistic Analysis of Cu2+-en-S2O32− Gold Leaching with Nickel-Bearing Pyrite

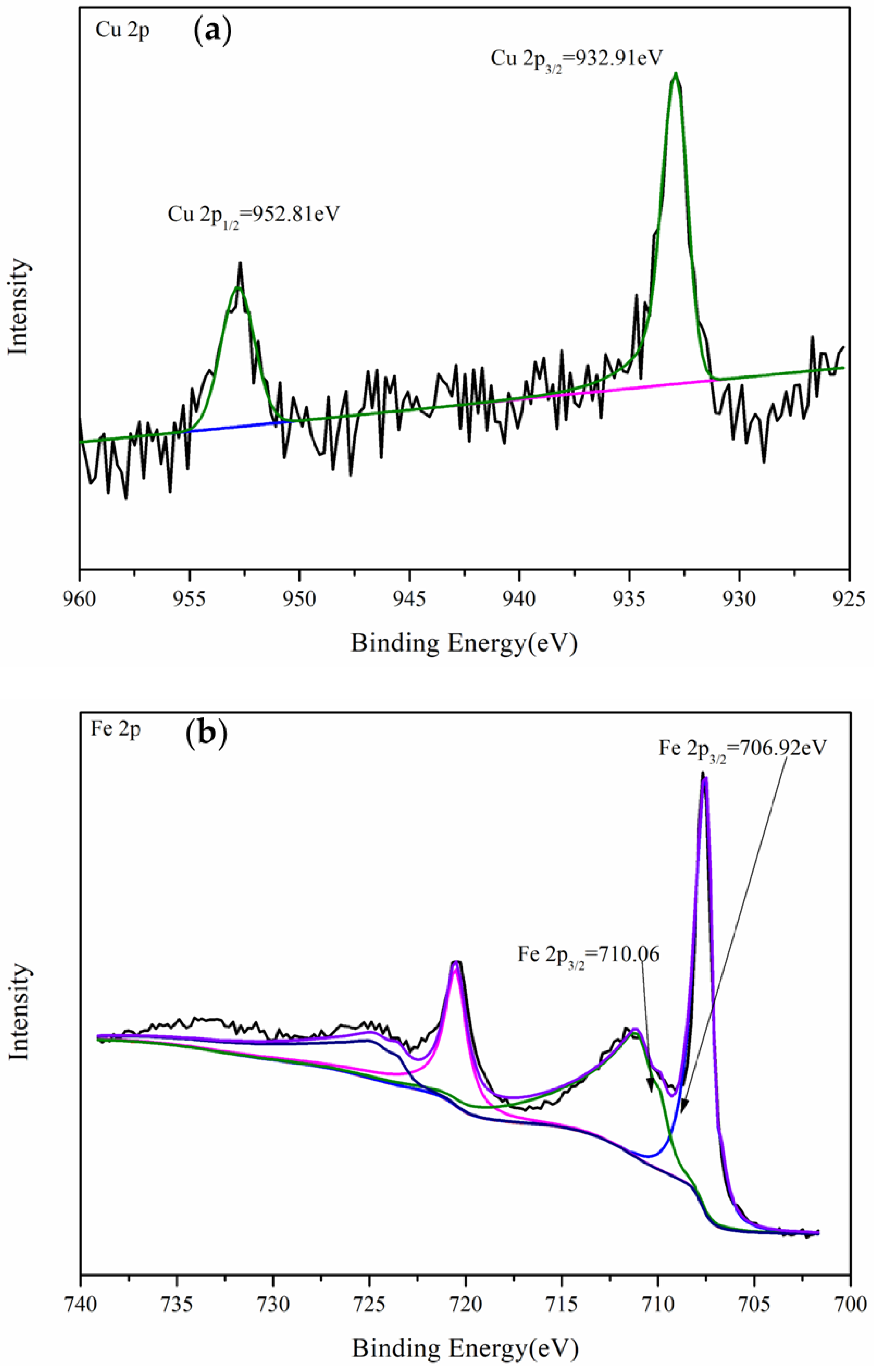

3.4.1. XPS Analysis of Gold Foil After Leaching

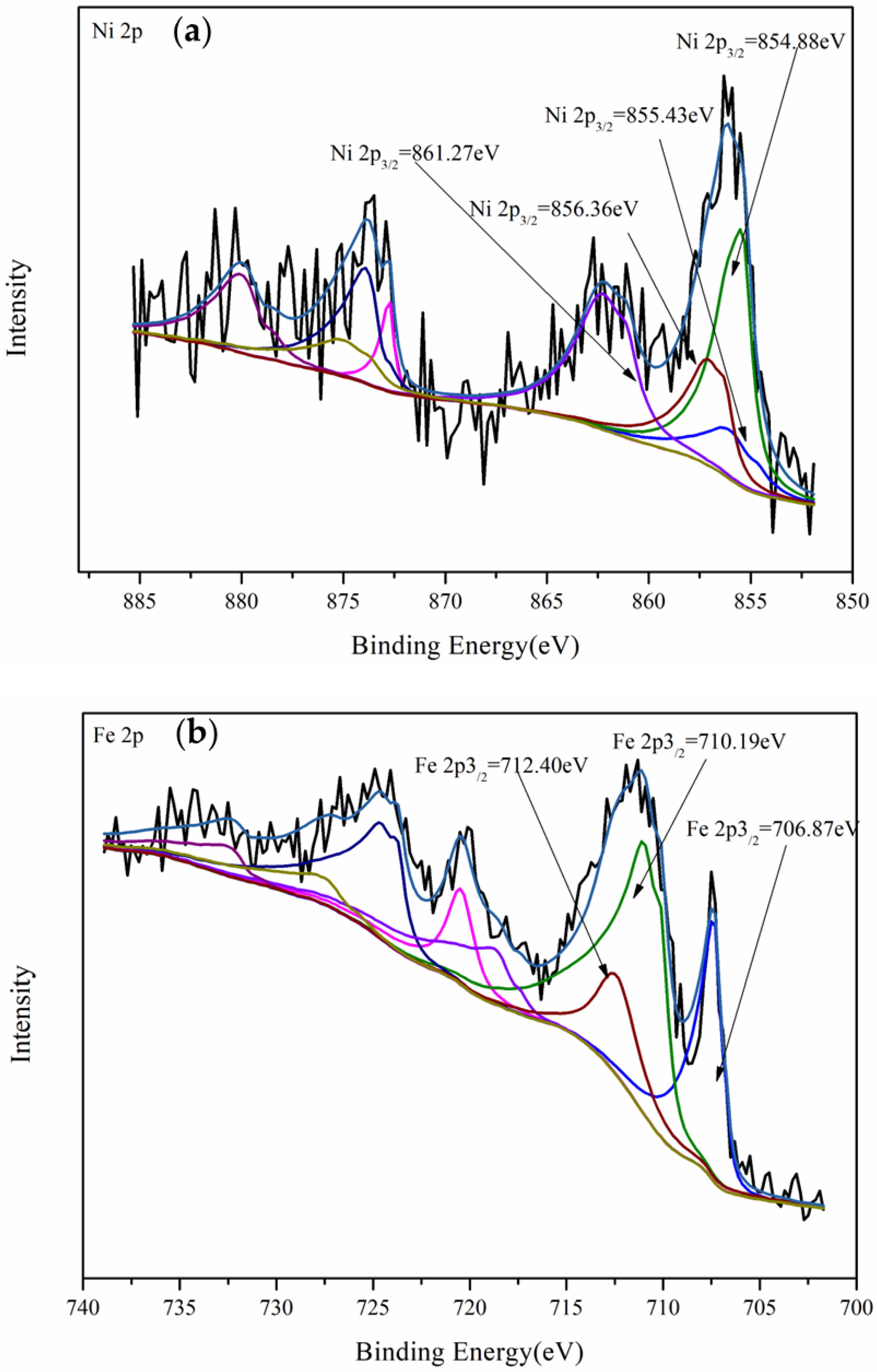

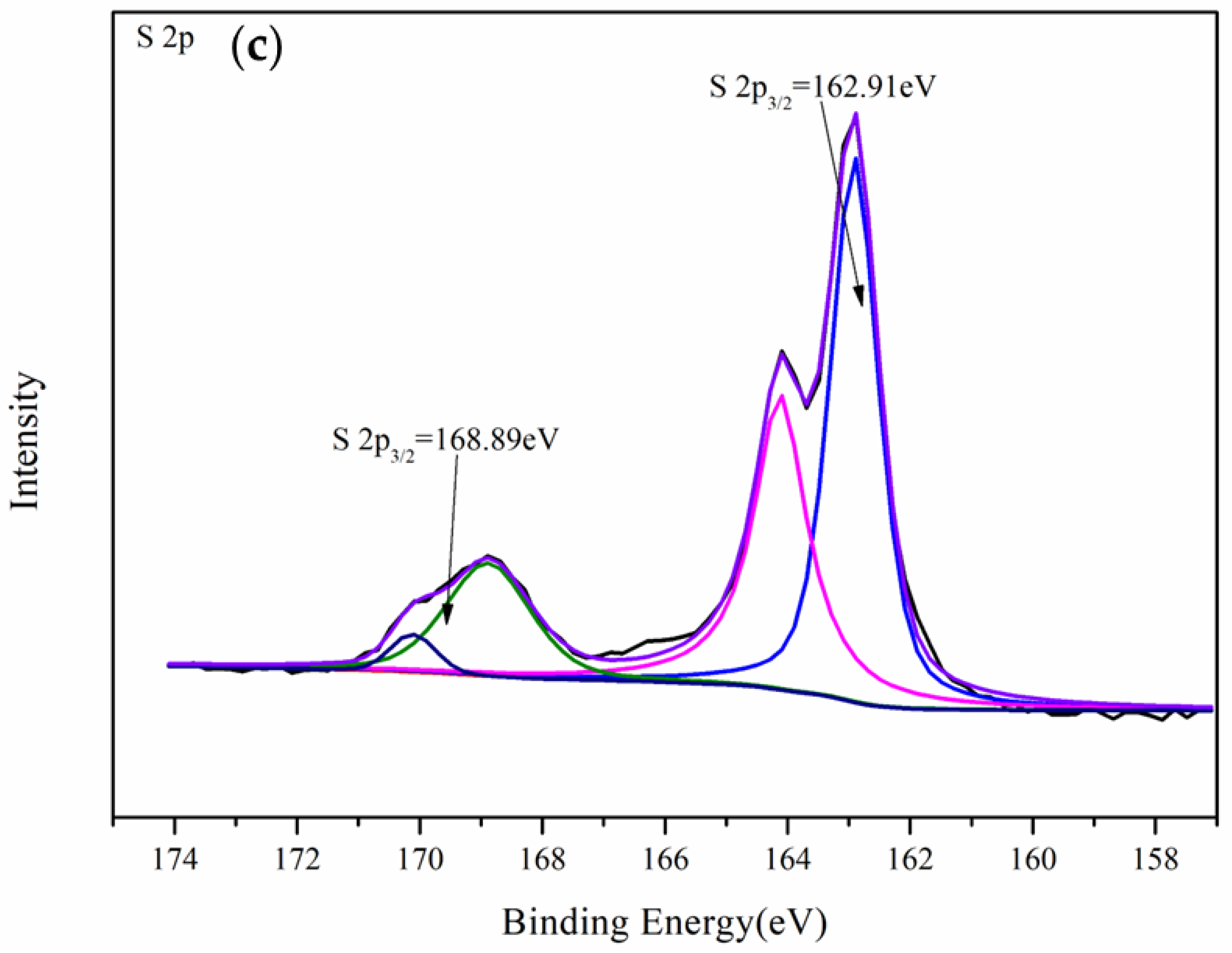

3.4.2. XPS Analysis of Nickel-Bearing Pyrite After Leaching

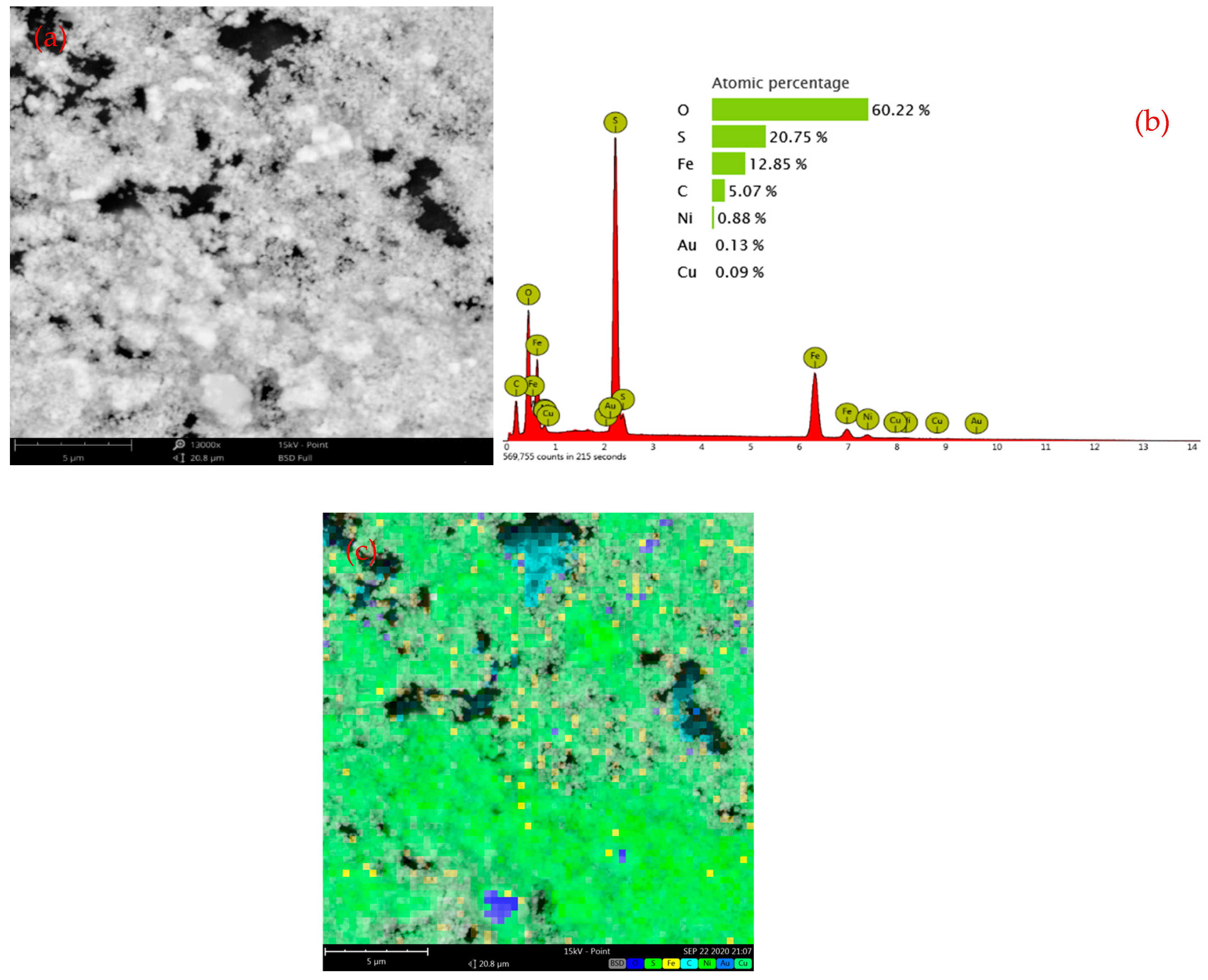

3.4.3. SEM Analysis of Nickel-Bearing Pyrite After Leaching

3.4.4. Mechanism of the Catalytic Decomposition of Thiosulfate by Nickel-Bearing Pyrite in the Cu2+-en-S2O32− Gold Leaching System

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lampinen, M.; Laari, A.; Turunen, I. Ammoniacal thiosulfate leaching of pressure oxidized sulfide gold concentrate with low reagent consumption. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 151, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Jeffrey, M.I. The effect of sulfide minerals on the leaching of gold in aerated cyanide solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2006, 82, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasab, M.G.; Rashchi, F.; Raygan, S. Chloride–hypochlorite leaching and hydrochloric acid washing in multi-stages for extraction of gold from a refractory concentrate. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 142, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemzadehfini, M.; Ficeriová, J.; Abkhoshk, E.; Shahraki, B.K. Effect of mechanical activation on thiosulfate leaching of gold from complex sulfide concentrate. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2011, 21, 2744–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasab, M.G.; Raygan, S.; Rashchi, F. Chloride–hypochlorite leaching of gold from a mechanically activated refractory sulfide concentrate. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 138, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahandra, F.G.A. Novel Extraction Process for Gold Recovery from Thiosulfate Solution Using Phosphonium Ionic Liquids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 8179–8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, C.A.; McMullen, J.; Thomas, K.G.; Wells, J.A. Recent advances in the development of an alternative to the cyanidation process: Thiosulfate leaching and resin in pulp. Min. Metall. Explor. 2003, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Van Deventer, J.S. Ammoniacal thiosulphate leaching of gold in the presence of pyrite. Hydrometallurgy 2006, 82, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.B.; Zhang, X.; Bin, X.U.; Qian, L.I.; Jiang, T.; Wang, Y.X. Effect of arsenopyrite on thiosulfate leaching of gold. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2015, 25, 3454–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Schoonen, M.A. The stability of thiosulfate in the presence of pyrite in low-temperature aqueous solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1995, 59, 4605–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zi, F.; Hu, X.; Chen, Y.; Guo, L.; Yu, H. The catalytic decomposition of thiosulfate by pyrite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 436, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Feng, Q. The effect of As doping concentration on the electronic structure of FeS2. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2017, 27, 414–422. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.H.; Ye, C.; Li, Y.Q. Effect of vacancy defects on electronic properties and activation of sphalerite (110) surface by first-principles. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2010, 20, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caban-Acevedo, M.; Faber, M.S.; Tan, Y.; Hamers, R.J.; Jin, S. Synthesis and properties of semiconducting iron pyrite (FeS2) nanowires. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1977–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, F.; Sun, G.; Hu, R.; Hu, D.; Wei, C. Electron Hole-Core Characteristics of Pyrites from the Main Types of Gold Deposits in China and Affecting Factors. Acta Mineral. Sin. 2004, 24, 211–217. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson, M.; Yenial-Arslan, U.; Evans, C.; Curtis-Morar, C.; O’Donnell, R.; Parbhakar-Fox, A.; Forbes, E. Effect of pyrite textures and composition on flotation performance: A review. Miner. Eng. 2023, 201, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Chen, J.H.; Guo, J. DFT study of influences of As, Co and Ni impurities on pyrite (100) surface oxidation by O2 molecule. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 24, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ma, W.; Zhang, G.-F.; Feng, Q.-M. First-Principle Study of Electronic Structure and Optical Property of Cu/Co Doped FeS2. Acta Opt. Sin. 2016, 36, 1016001. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mingyue, Z. Ni-Doped FeS: Solvothermal Synthesis and the Visible-Light Photocatalytic Properties. Chin. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 31, 1119–1124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, X.; Zi, F.; Yang, P.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S. Environmentally friendly extraction of gold from refractory concentrate using a copper–ethylenediamine–thiosulfate solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Yu, Q.; Hu, X.; Zi, F.; Yu, H. The effect of ammonia on the anodic process of gold in copper-free thiosulfate solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, E123–E129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Chi, H.; Zi, F.; Hu, X.; Yu, H.; He, S. The effect of cobalt and nickel ions on gold dissolution in a thiosulfate-ethylenediamine (en)-Cu2+ system. Miner. Eng. 2015, 83, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Gao, P.; Han, Y.; Li, Y. Mechanism for suspension magnetization roasting of iron ore using straw-type biomass reductant. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2021, 31, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kou, J.; Sun, C. A comparative study of the thermal decomposition of pyrite under microwave and conventional heating with different temperatures. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 138, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xia, Y.; Wei, G.; Zhou, J.; Liang, X.; Xian, H.; Zhu, J.; He, H. Distinct effects of transition metal (cobalt, manganese and nickel) ion substitutions on the abiotic oxidation of pyrite: In view of hydroxyl radical production. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2022, 321, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Schoonen, M.A.; Strongin, D.R. Thiosulfate oxidation: Catalysis of synthetic sphalerite doped with transition metals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1996, 60, 4701–4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, K.; Gao, W.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Jiang, T. Eco-friendly and low-energy innovative scheme of self-generated thiosulfate by atmospheric oxidation for green gold extraction. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Van Deventer, J.S. Thiosulphate leaching of gold in the presence of orthophosphate and polyphosphate. Hydrometallurgy 2011, 106, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, Z.; Weyer, S.; Horn, I.; Huo, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, N.; Zhang, Q.; Han, F.; Feng, H. Metal source and ore precipitation mechanism of the Ashawayi orogenic gold deposit, southwestern Tianshan Orogen, western China: Constraints from textures and trace elements in pyrite. Ore Geol. Rev. 2023, 157, 105452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, P.; Leinen, D.; Pascual, J.; Ramos-Barrado, J.R.; Grez, P.; Gomez, H.; Schrebler, R.; Del Río, R.; Cordova, R. A chemical, morphological, and electrochemical (XPS, SEM/EDX, CV, and EIS) analysis of electrochemically modified electrode surfaces of natural chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) and pyrite (FeS2) in alkaline solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 4977–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acres, R.G.; Harmer, S.L.; Beattie, D.A. Synchrotron XPS studies of solution exposed chalcopyrite, bornite, and heterogeneous chalcopyrite with bornite. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2010, 94, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laajalehto, K.; Kartio, I.; Nowak, P. XPS study of clean metal sulfide surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1994, 81, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroubaix, G.; Marcus, P. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy analysis of copper and zinc oxides and sulphides. Surf. Interface Anal. 1992, 18, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metal Ion | Complexation | LogK |

|---|---|---|

| Ni2+ | Ni(en)2+ | 7.52 |

| Ni(en)22+ | 13.84 | |

| Cu+ | Cu(en)2+ | 10.8 |

| Cu2+ | Cu(en)2+ | 10.67 |

| Cu(en)22+ | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, X.; Zhang, T.; Qin, W.; Zhang, H. Effect of Nickel Impurities in Pyrite on Catalytic Degradation of Thiosulfate. Metals 2024, 14, 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/met14111256

Qin X, Zhang T, Qin W, Zhang H. Effect of Nickel Impurities in Pyrite on Catalytic Degradation of Thiosulfate. Metals. 2024; 14(11):1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/met14111256

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Xuecong, Tao Zhang, Wenhua Qin, and Hongbo Zhang. 2024. "Effect of Nickel Impurities in Pyrite on Catalytic Degradation of Thiosulfate" Metals 14, no. 11: 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/met14111256

APA StyleQin, X., Zhang, T., Qin, W., & Zhang, H. (2024). Effect of Nickel Impurities in Pyrite on Catalytic Degradation of Thiosulfate. Metals, 14(11), 1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/met14111256