Granzyme B PET Imaging Enables Detection of CAR T-Cell Therapy Response in a Human Melanoma Mouse Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Studies

2.2. Cell Culture and Development of Human Melanoma Mouse Model

2.3. CAR T-Cell Treatment

2.4. 68Ga-NOTA-CYT-200 Labeling and PET Imaging

2.5. Immunohistochemical (IHC) and Immunofluorescent Staining

2.6. Cytokine Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

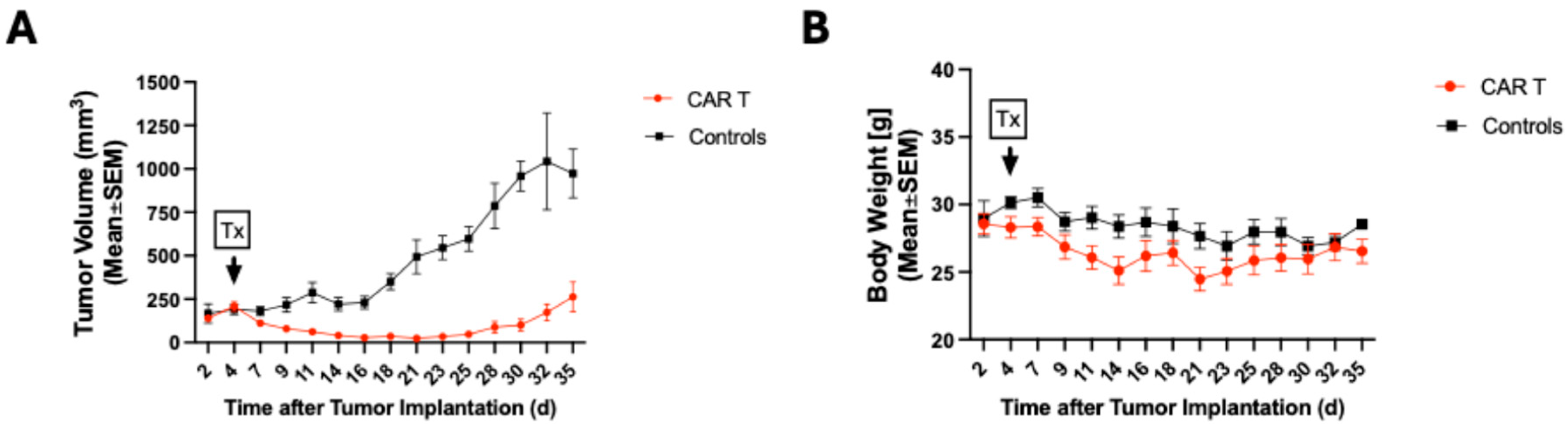

3.1. CAR T-Cell Therapy Delays Tumor Growth of Melanoma Tumors

3.2. 68Ga-NOTA-CYT-200 PET Imaging Predicts Treatment Response of Tumors Treated with CAR T Cells

3.3. CAR T-Cell-Treated Mice Showed Greater Tracer Uptake in the Colon

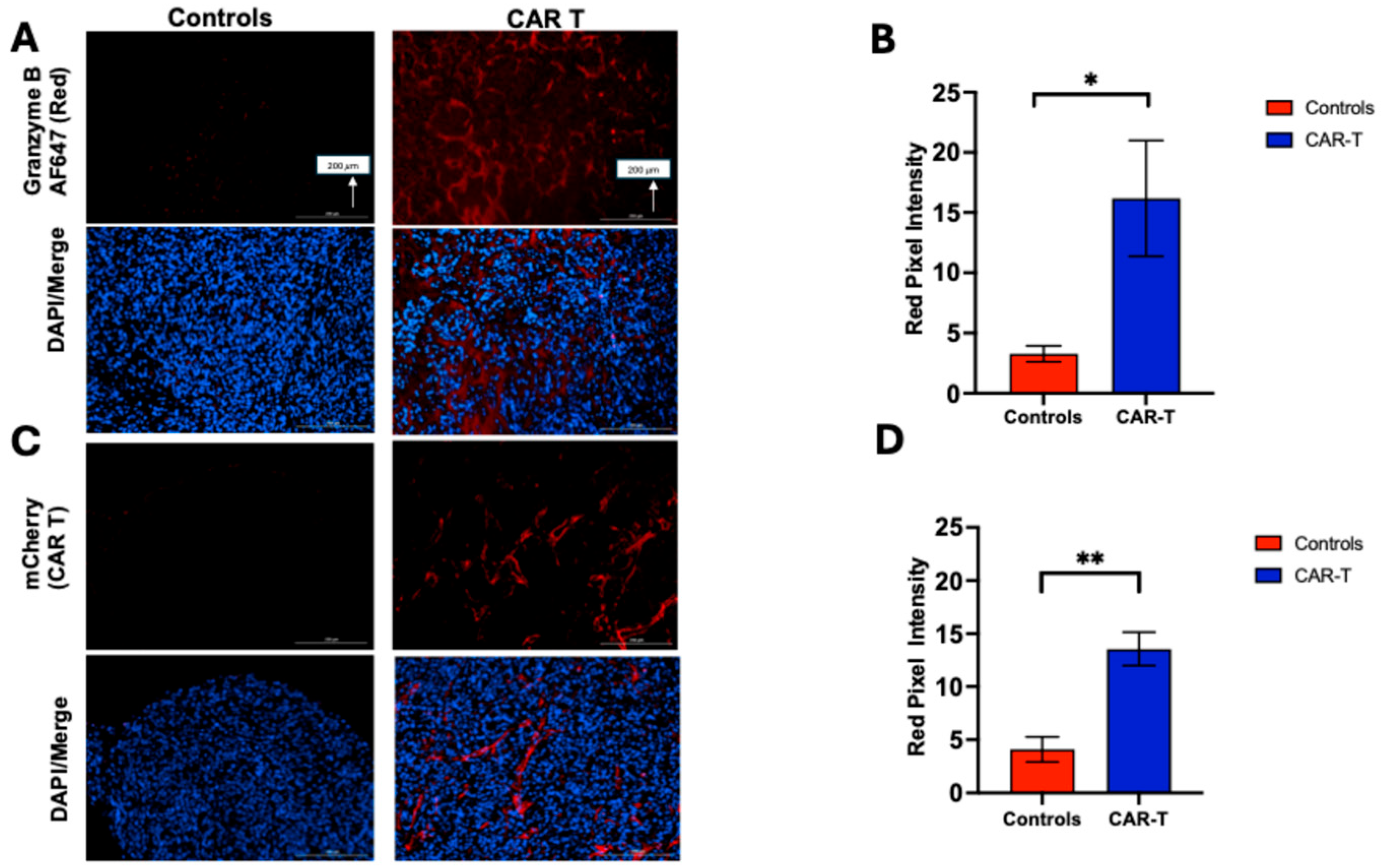

3.4. Tumor Samples Were Analyzed by Immunostaining (IHC and Immunofluorescence) to Assess Granzyme B Expression and CAR T-Cell Infiltration

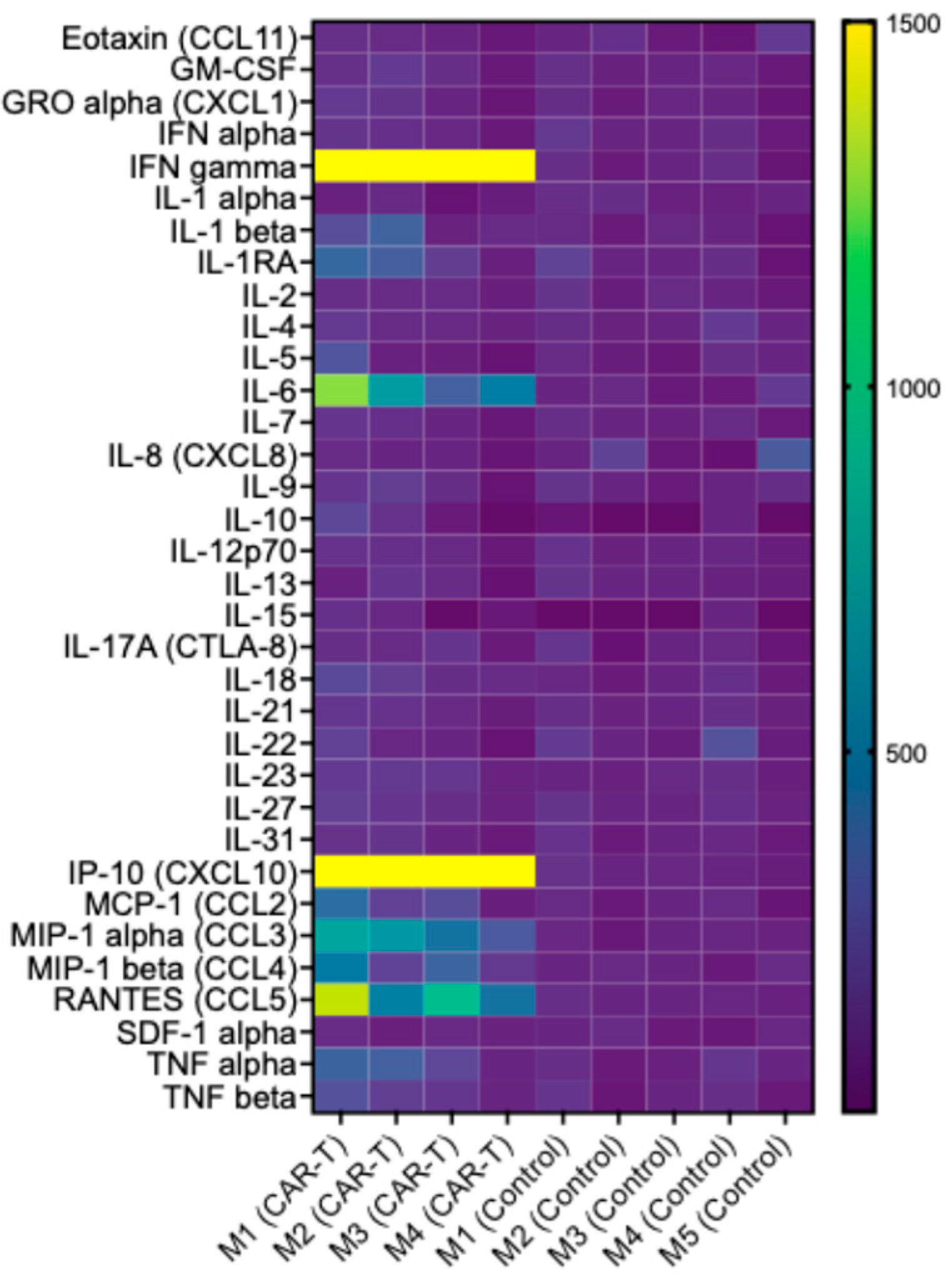

3.5. CAR T-Cell Therapy Is Associated with a Targeted Increase in Inflammatory Mediators, Consistent with Activation of an Antitumor Immune Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A375 | Human melanoma cell line |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CAR T | Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell |

| CBR | Colon-to-blood Ratio |

| CCL | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand |

| CD3/CD8 | Cluster of Differentiation 3/8 |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte |

| CXCL-10 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 10 (Interferon Gamma-Induced Protein 10 |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| GZB | Granzyme B |

| HEPES | 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic Acid |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IFN-ϒ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LBR | Liver-to-blood Ratio |

| LuBR | Lung-to-blood Ratio |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MFI | Mean Fluorescence Imaging |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| NSG | NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (immunodeficient mouse strain) |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PERCIST | PET Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| RECIST | Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute (cell culture medium) |

| RSNA | Radiologic Society of North America |

| SAPE | Streptavidin R-Phycoerythrin Conjugate |

| s.c. | Subcutaneous |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| SUV | Standard Uptake Value |

| TBR | Tumor-to-blood Ratio |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| v/v | Volume per volume |

References

- Guy, G.P., Jr.; Thomas, C.C.; Thompson, T.; Watson, M.; Massetti, G.M.; Richardson, L.C. Vital signs: Melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982–2030. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Melanoma. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk-Krauss, J.; Stein, J.A.; Weber, J.; Polsky, D.; Geller, A.C. New Systematic Therapies and Trends in Cutaneous Melanoma Deaths Among US Whites, 1986–2016. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, A.S.; Ma, Q.; Liu, D.L.; Junghans, R.P. Anti-GD3 chimeric sFv-CD28/T-cell receptor zeta designer T cells for treatment of metastatic melanoma and other neuroectodermal tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 2769–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltantoyeh, T.; Akbari, B.; Karimi, A.; Chalbatani, G.M.; Ghahri-Saremi, N.; Hadjati, J.; Hamblin, M.R.; Mirzaei, H.R. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma: Challenges and Road Ahead. Cells 2021, 10, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Wu, X.; Yan, J.; Yu, H.; Xu, L.; Chi, Z.; Sheng, X.; Si, L.; Cui, C.; Dai, J.; et al. Anti-GD2/4-1BB chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for the treatment of Chinese melanoma patients. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.C.; Sterner, R.M. CAR-T cell therapy: Current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Boesteanu, A.C.; Binder, Z.A.; Xu, C.; Reid, R.A.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Cook, D.R.; Thokala, R.; Blouch, K.; McGettigan-Croce, B.; et al. Checkpoint Blockade Reverses Anergy in IL-13Ralpha2 Humanized scFv-Based CAR T Cells to Treat Murine and Canine Gliomas. Mol. Ther.–Oncolytics 2018, 11, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomasso, B.D.; Park, J.H.; Salloum, D.; Riviere, I.; Flynn, J.; Mead, E.; Halton, E.; Wang, X.; Senechal, B.; Purdon, T.; et al. Clinical and Biological Correlates of Neurotoxicity Associated with CAR T-cell Therapy in Patients with B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 958–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.; Riviere, I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, P.; Haj-Mirzaian, A.; Prabhu, S.; Ataeinia, B.; Esfahani, S.A.; Mahmood, U. Granzyme B PET Imaging for Assessment of Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2024, 65, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimer, B.M.; Wehrenberg-Klee, E.; Dubois, F.; Mehta, A.; Kalomeris, T.; Flaherty, K.; Boland, G.; Mahmood, U. Granzyme B PET Imaging as a Predictive Biomarker of Immunotherapy Response. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 2318–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, G.P.; Kramer, H.; Reiser, M.F.; Glaser, C. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography-computed tomography in oncology. Top. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2007, 18, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahl, R.L.; Jacene, H.; Kasamon, Y.; Lodge, M.A. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J. Nucl. Med. 2009, 50 (Suppl. S1), 122S–150S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellingson, B.M.; Chung, C.; Pope, W.B.; Boxerman, J.L.; Kaufmann, T.J. Pseudoprogression, radionecrosis, inflammation or true tumor progression? challenges associated with glioblastoma response assessment in an evolving therapeutic landscape. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2017, 134, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Shen, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, H.; et al. Noninvasive interrogation of CD8+ T cell effector function for monitoring early tumor responses to immunotherapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e161065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summer, P.; Gallon, N.; Bulmer, N.; Mahmood, U.; Heidari, P. Granzyme B PET Imaging Enables Early Assessment of Immunotherapy Response in a Humanized Melanoma Mouse Model. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaSalle, T.; Austin, E.E.; Rigney, G.; Wehrenberg-Klee, E.; Nesti, S.; Larimer, B.; Mahmood, U. Granzyme B PET imaging of immune-mediated tumor killing as a tool for understanding immunotherapy response. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, M.; Lan, X. Multimodality reporter gene imaging: Construction strategies and application. Theranostics 2018, 8, 2954–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jähner, D.; Stuhlmann, H.; Stewart, C.L.; Harbers, K.; Löhler, J.; Simon, I.; Jaenisch, R. De novo methylation and expression of retroviral genomes during mouse embryogenesis. Nature 1982, 298, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente-Pereira, A.C.; Burnet, J.; Ellison, D.; Foster, J.; Davies, D.M.; van der Stegen, S.; Burbridge, S.; Chiapero-Stanke, L.; Wilkie, S.; Mather, S.; et al. Trafficking of CAR-engineered human T cells following regional or systemic adoptive transfer in SCID beige mice. J. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 31, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weist, M.R.; Starr, R.; Aguilar, B.; Chea, J.; Miles, J.K.; Poku, E.; Gerdts, E.; Yang, X.; Priceman, S.J.; Forman, S.J.; et al. PET of Adoptively Transferred Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells with 89Zr-Oxine. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, P.; Li, Z.; Choi, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, F.; Lee, D.Y.; Figliola, M.; Huls, H.; Lee, D.A.; Zal, T.; et al. Imaging of genetically engineered T cells by PET using gold nanoparticles complexed to Copper-64. Integr. Biol. 2013, 5, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.C.; Kann, M.C.; Bailey, S.R.; Haradhvala, N.J.; Llopis, P.M.; Bouffard, A.A.; Scarfó, I.; Leick, M.B.; Grauwet, K.; Berger, T.R.; et al. CAR T cell killing requires the IFNgammaR pathway in solid but not liquid tumours. Nature 2022, 604, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonkoua, L.A.K.; Sirpilla, O.; Sakemura, R.; Siegler, E.L.; Kenderian, S.S. CAR T cell therapy and the tumor microenvironment: Current challenges and opportunities. Mol. Ther.–Oncolytics 2022, 25, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Riddell, S.R. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cell Therapy: Challenges to Bench-to-Bedside Efficacy. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauken, K.E.; Wherry, E.J. Overcoming T cell exhaustion in infection and cancer. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.A.; Heidari, P.; Ataeinia, B.; Sinevici, N.; Sise, M.E.; Colvin, R.B.; Wehrenberg-Klee, E.; Mahmood, U. Non-invasive Detection of Immunotherapy-Induced Adverse Events. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5353–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, E.; CombadièrE, C.; Iga, M.; Boissonnas, A.; Bonduelle, O.; Maho, M.; Debré, P.; Combadiere, B. Intratumoral CC chemokine ligand 5 overexpression delays tumor growth and increases tumor cell infiltration. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 3755–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, A.C.; Escribà-Garcia, L.; Alvarez-Fernández, C.; Briones, J. CAR T-Cell Therapy Predictive Response Markers in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma and Therapeutic Options After CART19 Failure. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 904497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Summer, P.; Bulmer, N.; Prabhu, S.; Gallon, N.; Larson, R.C.; Maus, M.V.; Mahmood, U.; Heidari, P. Granzyme B PET Imaging Enables Detection of CAR T-Cell Therapy Response in a Human Melanoma Mouse Model. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233058

Summer P, Bulmer N, Prabhu S, Gallon N, Larson RC, Maus MV, Mahmood U, Heidari P. Granzyme B PET Imaging Enables Detection of CAR T-Cell Therapy Response in a Human Melanoma Mouse Model. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233058

Chicago/Turabian StyleSummer, Priska, Niklas Bulmer, Suma Prabhu, Naomi Gallon, Rebecca C. Larson, Marcela V. Maus, Umar Mahmood, and Pedram Heidari. 2025. "Granzyme B PET Imaging Enables Detection of CAR T-Cell Therapy Response in a Human Melanoma Mouse Model" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233058

APA StyleSummer, P., Bulmer, N., Prabhu, S., Gallon, N., Larson, R. C., Maus, M. V., Mahmood, U., & Heidari, P. (2025). Granzyme B PET Imaging Enables Detection of CAR T-Cell Therapy Response in a Human Melanoma Mouse Model. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3058. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233058