Machine Learning Model with Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) as a Proof-of-Concept Tool for Predicting Group A Streptococcus (GAS) emm-Type in the Pediatric Population

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Collection and Microbial Identification

2.2. DNA Extraction and Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Sample Preparation and Spectra Acquisition

2.4. Exploratory Analysis and Machine Learning Classifier Creation

3. Results

3.1. GAS Strains Description

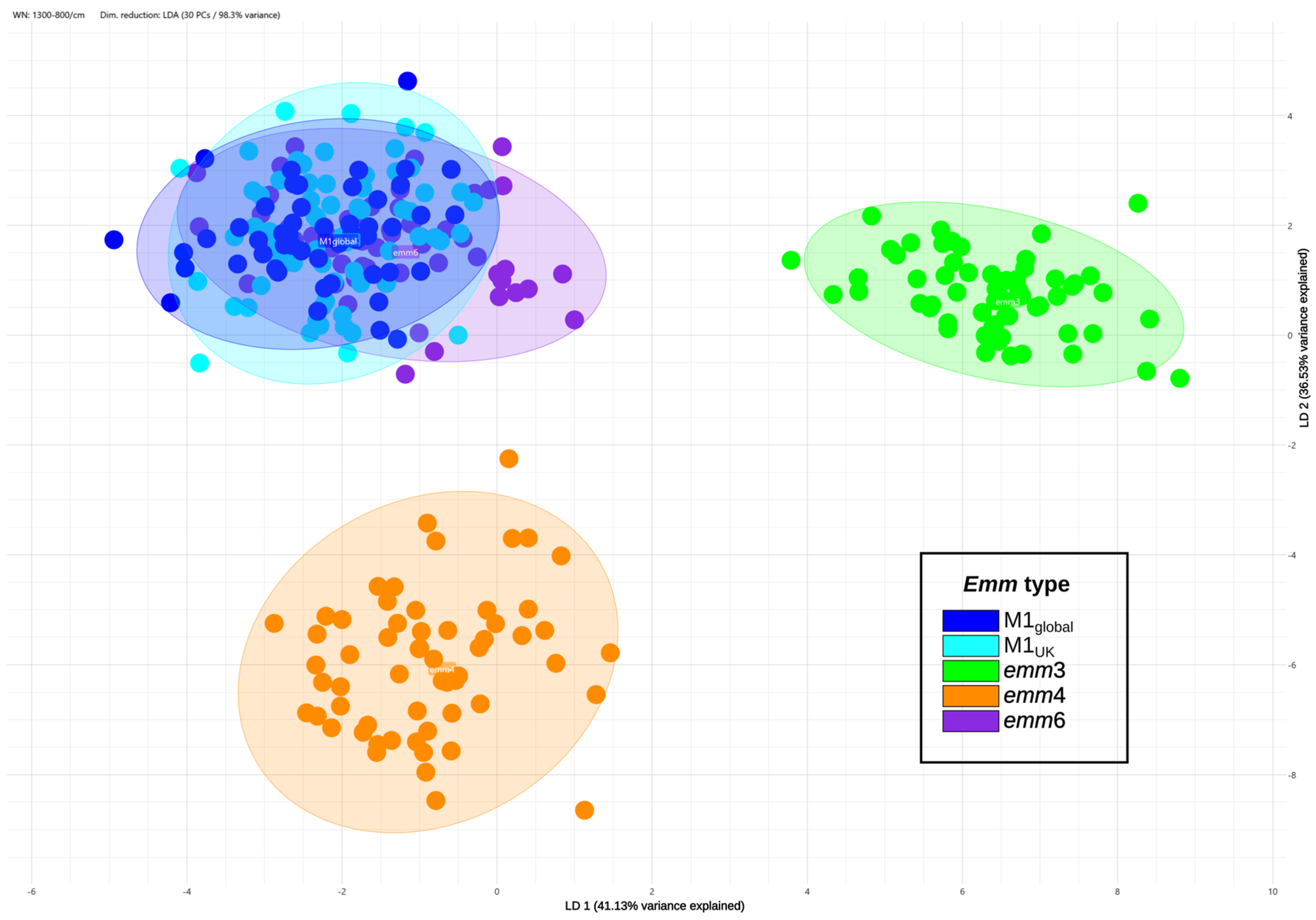

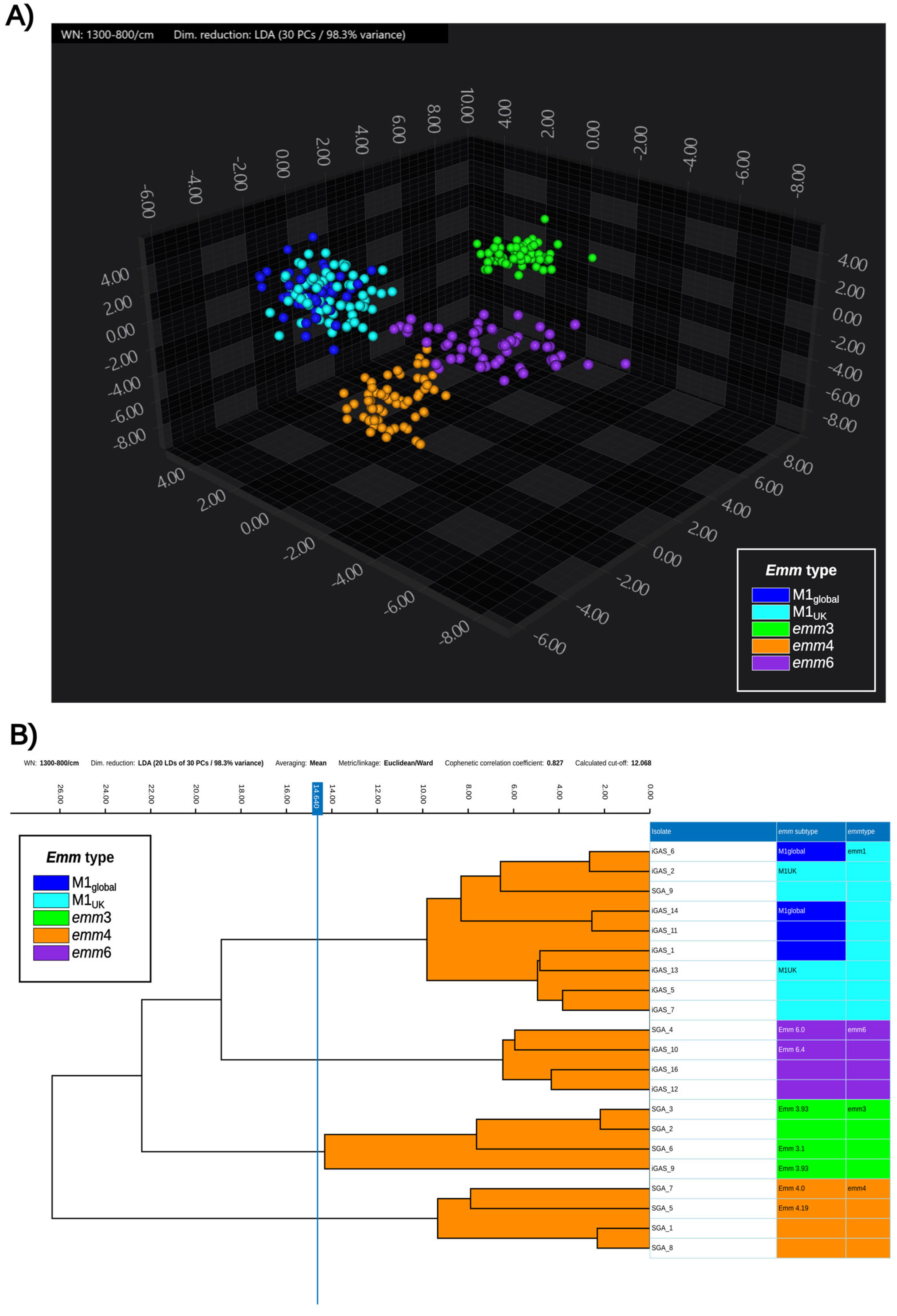

3.2. Exploratory Analysis

3.3. Classifiers Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GAS | Group A Streptococcus |

| iGAS | Invasive GAS infections |

| IR | Infrared |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| RBF | Radial Basis Functions |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

References

- Walker, M.J.; Barnett, T.C.; McArthur, J.D.; Cole, J.N.; Gillen, C.M.; Henningham, A.; Sriprakash, K.S.; Sanderson-Smith, M.L.; Nizet, V. Disease manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of Group A Streptococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 264–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carapetis, J.R.; Steer, A.C.; Mulholland, E.K.; Weber, M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, S.; Rivera-Hernandez, T.; Curren, B.F.; Harbison-Price, N.; De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Jespersen, M.G.; Davies, M.R.; Walker, M.J. Pathogenesis, epidemiology and control of Group A Streptococcus infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valcarcel Salamanca, B.; Cyr, P.R.; Bentdal, Y.E.; Watle, S.V.; Wester, A.L.; Strand, Å.M.W.; Bøås, H. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal infections (iGAS) in children and older adults, Norway, 2022 to 2024. Euro Surveill. 2024, 29, 2400242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gier, B.; Marchal, N.; de Beer-Schuurman, I.; te Wierik, M.; Hooiveld, M.; ISIS-AR Study Group; GAS Study Group; de Melker, H.E.; van Sorge, N.M. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal (Streptococcus pyogenes) infections (iGAS) in young children in the Netherlands, 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28, 2200941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beres, S.B.; Olsen, R.J.; Long, S.W.; Langley, R.; Williams, T.; Erlendsdottir, H.; Smith, A.; Kristinsson, K.G.; Musser, J.M. Increase in invasive Streptococcus pyogenes M1 infections with close evolutionary genetic relationship, Iceland and Scotland, 2022 to 2023. Euro Surveill. 2024, 29, 2400129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangioni, D.; Fox, V.; Saltini, P.; Lombardi, A.; Bussini, L.; Carella, F.; Cariani, L.; Comelli, A.; Matinato, C.; Muscatello, A.; et al. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal infections in Milan, Italy: A genomic and clinical characterization. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1287522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, R.; Henderson, K.L.; Coelho, J.; Hughes, H.; Mason, E.L.; Gerver, S.M.; Demirjian, A.; Watson, C.; Sharp, A.; Brown, C.S.; et al. Increase in invasive group A streptococcal infection notifications, England, 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023, 28, 2200942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.R.; Keller, N.; Brouwer, S.; Jespersen, M.G.; Cork, A.J.; Hayes, A.J.; Pitt, M.E.; De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Harbison-Price, N.; Bertolla, O.M.; et al. Detection of Streptococcus pyogenes M1UK in Australia and characterization of the mutation driving enhanced expression of superantigen SpeA. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.K.; Zhi, X.; Vieira, A.; Whitwell, H.J.; Schricker, A.; Jauneikaite, E.; Li, H.; Yosef, A.; Andrew, I.; Game, L.; et al. Characterization of emergent toxigenic M1UK Streptococcus pyogenes and associated sublineages. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, mgen000994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.; Wan, Y.; Ryan, Y.; Li, H.K.; Guy, R.L.; Papangeli, M.; Huse, K.K.; Reeves, L.C.; Soo, V.W.C.; Daniel, R.; et al. Rapid expansion and international spread of M1UK in the post-pandemic UK upsurge of Streptococcus pyogenes. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/strep-lab/php/group-a-strep/emm-typing.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Feng, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Zhang, L.; Shen, H.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; et al. Protocol for bacterial typing using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. STAR Protoc. 2023, 4, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassem, A.; Abbas, L.; Coutinho, O.; Opara, S.; Najaf, H.; Kasperek, D.; Pokhrel, K.; Li, X.; Tiquia-Arashiro, S. Applications of Fourier Transform-Infrared spectroscopy in microbial cell biology and environmental microbiology: Advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1304081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchaamba, F.; Stephan, R. A Comprehensive Methodology for Microbial Strain Typing Using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Methods Protoc. 2024, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurie-Weinberger, M.N.; Temkin, E.; Kastel, O.; Bechor, M.; Bychenko-Banyas, D.; Efrati-Epchtien, R.; Levi, G.D.; Rakovitsky, N.; Keren-Paz, A.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Use of a national repository of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy spectra enables fast detection of silent outbreaks and prevention of spread of new antibiotic-resistant sequence types. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2025, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Ruiz, M.; Wang-Wang, J.H.; Bordoy, A.E.; Rodríguez-Ponga, B.; Pagan, N.; Hidalgo, J.; Quesada, M.D.; Giménez, M.; Cardona, P.J. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy for rapid Streptococcus pneumoniae serotyping in a tertiary care general hospital. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1565888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordovana, M.; Mauder, N.; Join-Lambert, O.; Gravey, F.; LeHello, S.; Auzou, M.; Pitti, M.; Zoppi, S.; Buhl, M.; Steinmann, J.; et al. Machine learning-based typing of Salmonella enterica O-serogroups by the Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy-based IR Biotyper system. J. Microbiol. Methods 2022, 201, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, T.M.; Rodrigues, L.S.; Krul, D.; Barbosa, S.D.C.; Siqueira, A.C.; Almeida, S.C.G.; Pacheco Souza, A.P.O.; Pillonetto, M.; Oliveira, R.; Moonen, C.G.J.; et al. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular serotype classification in pediatric patients with invasive infections. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1497377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrenna, G.; Rossitto, M.; Agosta, M.; Cortazzo, V.; Fox, V.; De Luca, M.; Lancella, L.; Gargiullo, L.; Granaglia, A.; Fini, V.; et al. First Evidence of Streptococcus pyogenes M1UK Clone in Pediatric Invasive Infections in Italy by Molecular Surveillance. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2024, 43, e421–e424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2023, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data 2010. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.E.; Lu, J.; Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Shovill.Faster SPAdes (or Better SKESA/Megahit/Velvet) Assembly of Illumina Reads 2018. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/shovill (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microbiological Diagnostic Unit Public Health Laboratory. Emmtyper—Emm Automatic Isolate Labeller (v0.2.0). 2021. Available online: https://github.com/MDU-PHL/emmtyper (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Seemann, T. mlst Tool 2022. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/mlst (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Seemann, T. Snippy: Fast Bacterial Variant Calling from NGS Reads 2015. Available online: https://github.com/tseemann/snippy (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Lynskey, N.N.; Jauneikaite, E.; Li, H.K.; Zhi, X.; Turner, C.E.; Mosavie, M.; Pearson, M.; Asai, M.; Lobkowicz, L.; Chow, J.Y.; et al. Emergence of dominant toxigenic M1T1 Streptococcus pyogenes clone during increased scarlet fever activity in England: A population-based molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passaris, I.; Mauder, N.; Kostrzewa, M.; Burckhardt, I.; Zimmermann, S.; van Sorge, N.M.; Slotved, H.C.; Desmet, S.; Ceyssens, P.J. Validation of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for Serotyping of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022, 60, e0032522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peri, A.M.; Chatfield, M.D.; Ling, W.; Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Harris, P.N.A.; Paterson, D.L. Rapid Diagnostic Tests and Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs for the Management of Bloodstream Infection: What Is Their Relative Contribution to Improving Clinical Outcomes? A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 79, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eubank, T.A.; Long, S.W.; Perez, K.K. Role of Rapid Diagnostics in Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222 (Suppl. S2), S103–S109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, R.; Itzek, A.; Marr, L.; Manzke, J.; Voigt, S.; Chapot, V.; van der Linden, M.; Rath, P.-M.; Hitzl, W.; Steinmann, J. Divergent effects of emm types 1 and 12 on invasive group A streptococcal infections-results of a retrospective cohort study, Germany 2023. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e0063724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azrad, M.; Matok, L.A.; Leshem, T.; Peretz, A. Comparison of FT-IR with whole-genome sequencing for identification of maternal-toneonate transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 2022, 202, 106603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candela, A.; Rodríguez-Temporal, D.; Lumbreras, P.; Guijarro-Sánchez, P.; Arroyo, M.J.; Vázquez, F.; Beceiro, A.; Bou, G.; Muñoz, P.; Oviaño, M.; et al. Multicenter evaluation of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy as a first-line typing tool for carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in clinical settings. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e0112224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera Patiño, C.P.; Soares, J.M.; Blanco, K.C.; Bagnato, V.S. Machine Learning in FTIR Spectrum for the Identification of Antibiotic Resistance: A Demonstration with Different Species of Microorganisms. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokal, K.; Channon-Wells, S.; Davis, C.; Estrada-Rivadeneyra, D.; Huse, K.K.; Lias, A.; Hamilton, S.; Guy, R.L.; Lamagni, T.; Nichols, S.; et al. Immunity to Streptococcus pyogenes and Common Respiratory Viruses at Age 0 to 4 Years After COVID-19 Restrictions. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2537808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.A.; de Gier, B.; Guy, R.L.; Coelho, J.; van Dam, A.P.; van Houdt, R.; Matamoros, S.; van den Berg, M.; Habermehl, P.E.; Moganeradj, K.; et al. Streptococcus pyogenes emm Type 3.93 Emergence, the Netherlands and England. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blairon, L.; Tré-Hardy, M.; Matheeussen, V.; Koster, S.D.; Cassart, M.; Heenen, S.; Nebbioso, A.; Vitali, N. Rare emm6.10 Streptococcus pyogenes Causing an Unusual Invasive Infection in a Child: Clinical and Genomic Insights. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odo, C.M.; Vega, L.A.; Mukherjee, P.; DebRoy, S.; Flores, A.R.; Shelburne, S.A. Emergent emm4 group A Streptococcus evidences a survival strategy during interaction with immune effector cells. Infect. Immun. 2024, 92, e00152-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | Material | Isolation Date | emm-Type | emm-Subtype | Present in Previous Paper [20] | iGAS | Training/Test Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iGAS_1 | Blood culture | 12 February 2023 | 1 | 1.0 (M1global) | Yes | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_2 | CSF | 6 April 2023 | 1 | 1.52 (M1UK) | Yes | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_3 † | Ear swab | 19 April 2023 | 12 | 12.101 | Yes | No | Test |

| iGAS_4 † | Skin swab | 19 April 2023 | 89 | 89.0 | Yes | No | Test |

| iGAS_5 | Pleural fluid | 19 April 2023 | 1 | 1.52 (M1UK) | Yes | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_6 | Blood culture | 11 December 2023 | 1 | 1.25 (M1global) | Yes | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_7 | Blood culture | 2 February 2024 | 1 | 1.0 (M1UK) | Yes | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_8 † | Synovial liquid | 1 December 2023 | 75 | 75.0 | Yes | Yes | Test |

| iGAS_9 | Wound drainage | 20 March 2024 | 3 | 3.93 | No | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_10 | Pus | 4 April 2024 | 6 | 6.4 | No | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_11 | Venous blood culture | 8 April 2024 | 1 | 1.3 (M1global) | No | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_12 | Blood culture | 4 April 2024 | 6 | 6.4 | No | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_13 | Venous blood culture | 8 April 2024 | 1 | 1.3 (M1UK) | No | Yes | Training |

| iGAS_14 | Pharyngeal swab | 7 April 2024 | 1 | 1.0 (M1global) | No | Yes | Training |

| SGA_1 | Pharyngeal swab | 9 April 2024 | 4 | 4.19 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_2 | Vulvar swab | 9 April 2024 | 3 | 3.93 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_3 | Pharyngeal swab | 9 April 2024 | 3 | 3.93 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_4 | Vulvar swab | 22 April 2024 | 6 | 6.0 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_5 | Anal swab | 22 April 2024 | 4 | 4.19 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_6 | Pustule swab | 20 April 2024 | 3 | 3.1 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_7 | Wound swab | 20 April 2024 | 4 | 4.0 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_8 | Anal swab | 17 May 2024 | 4 | 4.19 | No | No | Training |

| SGA_9 | Tracheal aspirate | 2 May 2023 | 1 | 1.0 (M1UK) | No | No | Training |

| iGAS_16 | Blood culture | 20 October 2024 | 6 | 6.4 | No | Yes | Training |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fox, V.; Vrenna, G.; Rossitto, M.; Raimondi, S.; Cristiano, M.; Cortazzo, V.; Agosta, M.; Lucignano, B.; Onori, M.; Tuccio Guarna Assanti, V.; et al. Machine Learning Model with Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) as a Proof-of-Concept Tool for Predicting Group A Streptococcus (GAS) emm-Type in the Pediatric Population. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233041

Fox V, Vrenna G, Rossitto M, Raimondi S, Cristiano M, Cortazzo V, Agosta M, Lucignano B, Onori M, Tuccio Guarna Assanti V, et al. Machine Learning Model with Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) as a Proof-of-Concept Tool for Predicting Group A Streptococcus (GAS) emm-Type in the Pediatric Population. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233041

Chicago/Turabian StyleFox, Valeria, Gianluca Vrenna, Martina Rossitto, Serena Raimondi, Marco Cristiano, Venere Cortazzo, Marilena Agosta, Barbara Lucignano, Manuela Onori, Vanessa Tuccio Guarna Assanti, and et al. 2025. "Machine Learning Model with Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) as a Proof-of-Concept Tool for Predicting Group A Streptococcus (GAS) emm-Type in the Pediatric Population" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233041

APA StyleFox, V., Vrenna, G., Rossitto, M., Raimondi, S., Cristiano, M., Cortazzo, V., Agosta, M., Lucignano, B., Onori, M., Tuccio Guarna Assanti, V., Lepanto, M. S., Essa, N., Tarissi De Jacobis, I., Campana, A., Raponi, M., Villani, A., Perno, C. F., & Bernaschi, P. (2025). Machine Learning Model with Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) as a Proof-of-Concept Tool for Predicting Group A Streptococcus (GAS) emm-Type in the Pediatric Population. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233041