1. Introduction

Genetic diversity is fundamental to the survival and adaptation of animal species, enabling populations to withstand environmental changes and avoid extinction. Variability in genes supports key traits such as disease resistance, reproductive success, and behavioral adaptability, making it a cornerstone of natural selection and conservation biology.

Recent studies have also demonstrated the usefulness of microsatellite markers and related molecular tools for assessing genetic diversity and identifying population structure in equine and livestock species, further highlighting their relevance for conservation genetics [

1,

2]

Microsatellites have become essential tools for studying genetic diversity and population structure since their adoption in the late 1980s. Their high polymorphism, reproducibility, and relatively low cost make them particularly effective for equine studies [

3,

4,

5]. These markers are widely used to assess genetic variation among breeds, supported by PCR amplification of flanking regions and electrophoretic separation to generate detailed genetic profiles [

6].

Despite the advances in molecular tools, little is known about the genetic composition of Tunisian horse breeds, particularly Arabian horses that hold cultural and economic importance. Previous studies using PCR and sequencing approaches have provided preliminary insights [

7,

8,

9], but comprehensive analyses remain limited. This gap highlights the need for molecular investigations to inform sustainable breeding and conservation strategies. Similar molecular investigations conducted in other horse and domestic animal populations have shown how such approaches substantially improve the understanding of genetic structure and support the development of more effective breeding and conservation strategies [

10].

The present study applies ISAG-FAO-recommended microsatellites to evaluate the genetic diversity and structure of Tunisian Arabian horses. Specifically, we investigate relationships between Eastern and Western lineages and assess their differentiation from Thoroughbreds. We hypothesize that Western Arabians maintain higher genetic diversity than Eastern Arabians, reflecting differences in breeding history. By addressing these questions, the study aims to provide a molecular foundation for conservation programs and sustainable management of Tunisian Arabian horse populations

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and DNA Extraction

A total of 130 horses were included in this study. Among them, 99 were Tunisian Arabian horses registered in the national studbook and classified into two lineages based on pedigree information: 36 Eastern (Oriental-type) Arabians and 63 Western (Occidental-type) Arabians. In addition, 31 English Thoroughbred horses were included as an outgroup to assess inter-population genetic differentiation.

Although sampling was performed to avoid obvious close relatives based on studbook information, no formal pedigree-based or molecular relatedness analysis was conducted. Therefore, some degree of relatedness within each lineage cannot be fully excluded.

Blood samples are collected from the jugular vein of animals and placed into vacuum tubes containing 5 mL vacuum tubes with 20 µL of K3 EDTA (BD Vacutainer®, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Genomic DNA was extracted using the PureLink Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Invitrogen™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), which enables rapid and efficient purification of genomic DNA. This kit is specifically designed to isolate high-quality DNA by separating it from other cellular and tissue components.

2.2. Microsatellites Used

Microsatellites selected for genotyping the Tunisian Arabian breed to assess intrapopulation genetic variability consist of a panel of 17 markers (

Table 1) recommended by the ISAG-FAO Advisory Group for global equine genetic diversity analysis, identification, and parentage verification [

11].

2.3. DNA Amplification by PCR

Genomic DNA was amplified using multiplex PCR with the Applied Biosystems Equine Genotyping Kit(Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), following FAO guidelines. Each PCR reaction contained 50 ng of genomic DNA. PCR conditions included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 1 h to amplify the targeted microsatellites. Each 25 µL reaction mixture contained specific components: 2.5 µL MgCl2 (25 mM), 0.2 µL dNTP (25 mM), 0.5 µL of each primer (25 pmol/µL), 0.2 µL Taq polymerase (5 U/µL), 50 ng DNA, and 2.5 µL of 5X buffer. Amplified products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis using an ABI Prism 3130 DNA Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and DNA fragment sizes were determined using GeneScan-500 LIZ with GeneMapper Software (Applied Biosystems, Ver. 4.).

2.4. Parameters of Genetic Variability

The level of variability was used to examine the genetic variety within the studied population. The Hardy–Weinberg’s law was applied to determine whether a population was in equilibrium. We calculated parameters to characterize genetic diversity. Direct comparison of allele frequencies is challenging when considering the genetic heterogeneity within populations. Utilizing the GenAlex program (version 6.2), the following were calculated.

2.4.1. The Intra-Population Parameters

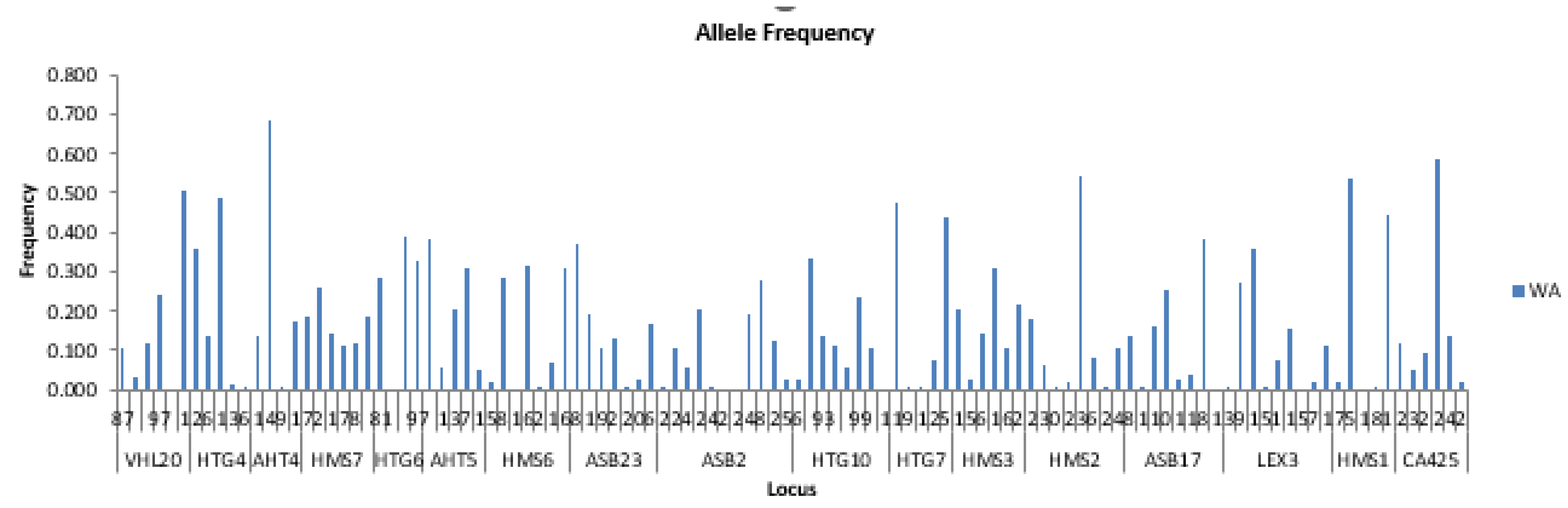

Allelic Frequency

Allelic frequency is the fundamental parameter used to describe and analyze genetic variability within a population [

21]. Thus, the frequency of an allele in a sample is equal to two times the range of homozygous genotypes for that allele (every homozygote consists of copies of the allele), plus the range of heterozygous genotypes containing that allele (each heterozygote incorporates one copy), divided by way of twice the overall range of people within the pattern (because every individual carry two alleles at this locus) [

22].

The formula to calculate the frequency (Pi) of allele i at locus k in population x is as follows:

nii represents the count of individuals homozygous for allele i at locus k.

ni denotes the count of individuals heterozygous for allele i at locus.

N is the total number of individuals typed at locus k.

ik represents the number of alleles at locus k.

The Rate of Heterozygosity

The most commonly used indicator of intra-population genetic variability, as generalized by [

23] and also referred to as the diversity index, is the probability that two random genes represent different alleles. It is equivalent to the expected heterozygosity rate (H) under the assumptions of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium [

24].

The heterozygosity rate corresponds to the proportion of heterozygous individuals at a given locus, and the overall heterozygosity of a population is obtained by averaging these values across all loci studied.

With:

N: the total number of loci studied.

Hi: the heterozygosity at locus i.

A good estimation of genetic variability is obtained through the population heterozygosity rate, as long as individuals within the population reproduce randomly.

Polymorphism Rate of Microsatellite Markers

Another way to assess the genetic variability of a population is by considering the number of alleles existing for the analyzed markers. A large number of alleles indicate greater diversity. A marker is considered highly polymorphic when it has at least two alleles, and the frequency of the most common allele is equal to or less than 0.95 [

25].

Fixation Index

The fixation index (Fis), also known as the inbreeding coefficient, is calculated from the difference between the proportion of individuals found in the heterozygous state (ho) and the expected heterozygosity rate (he) under the assumption of equilibrium [

26], according to the following formula:

With:

ho: observed heterozygosity.

he: expected heterozygosity, calculated from allele frequencies under the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium assumption.

This parameter reflects the differentiation of individuals within populations:

Fis = 1 signifies complete fixation (as in the case of self-fertilization).

0 < F < 1 indicates heterozygote deficit.

F = 0 indicates a population in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Fis < 0 indicates excess heterozygosity.

Observed and Effective Number of Alleles (Na and Ne)

The observed number of alleles (Na) corresponds to the total number of alleles detected at each locus within a population. The effective number of alleles (Ne) represents the number of equally frequent alleles required to generate the observed level of genetic diversity.

Ne is calculated as:

where

is the frequency of allele i.

2.4.2. Inter-Population Parameters

Wright’s F-Statistics

The most classical method of population characterization, and perhaps the oldest, is that of fixation indices proposed by [

27].

The F-statistics enable the description of population structure, the distribution of genetic variability between and within populations by estimating the standardized variance of allelic frequencies among subpopulations [

28].

FST, also known as fixation index, indicates the reduction in heterozygosity within subpopulations due to differences in average allelic frequencies. It provides information about population differentiation and subdivision effects. It represents the correlation between alleles within a subpopulation relative to all subpopulations. It takes a value of zero when all subpopulations have the same allelic frequencies and are in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. In cases of differentiation, its value ranges from 0 to 1 [

29].

0 < FST < 0.05: Weak differentiation

0.05 < FST < 0.15: Moderate differentiation

0.15 < FST < 0.25: Significant differentiation

F > 0.25: Very significant differentiation

FIT represents the reduction in heterozygosity between an individual and the theoretical overall population, considering both within- and between-subpopulation effects. It integrates the contributions of Fis (inbreeding within subpopulations) and FST (differentiation among subpopulations) according to the relationship:

A positive FIT indicates an overall deficit of heterozygotes in the global population, whereas negative values reflect an excess of heterozygosity. FIT therefore provides a global assessment of deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium across all subpopulations combined.

Nei’s Genetic Distance

In 1972, Nei proposed the most commonly used genetic distance, which is defined as follows:

With I = I′/r, where r is the number of loci, and I′ is the similarity index defined at each locus.

Indices 1 and 2 represent populations 1 and 2, respectively.

Dendrogram

The Neighbor-Joining [

24] tree-building method has been used to construct dendrograms from the distance matrix calculated according to Reynolds [

25].

Gene Flow (Nm)

Gene flow is defined as the exchange of multiple genes or their alleles between different related populations.

Gene flow represents the number of migrants exchanged between populations per generation. It is estimated from Wright’s fixation index using the formula: Nm = (1 − FST)/(4 FST). A high Nm value indicates substantial gene exchange and low genetic differentiation, whereas a low Nm value suggests restricted migration and stronger population subdivision. In this study, Nm was calculated for each pair of populations using their corresponding FST values to assess the level of connectivity among groups.

4. Discussion

The consistently high polymorphism rate across loci confirms the effectiveness of microsatellites as reliable markers for evaluating genetic diversity. Variations in allelic richness among populations are consistent with previous findings [

30], which emphasized that both the number of loci analyzed and the sample size strongly influence the total number of alleles detected. The elevated allelic richness observed in Syrian and Polish Arabians reflects a broad genetic background and less restrictive breeding practices, whereas the reduced values in Saudi, Egyptian, and Davenport horses suggest narrower genetic pools shaped by selective breeding. The slightly higher diversity recorded in Western compared to Eastern Arabian horses further indicates that historical crossbreeding and the introduction of Western bloodlines particularly in Tunisia have contributed to enhanced genetic variability. These results highlight the importance of maintaining and conserving genetic diversity in horse populations through sustainable breeding and conservation programs. These observations are in accordance with recent findings in other equine and livestock populations, where microsatellite-based analyses have proven effective in characterizing genetic variation and guiding conservation decisions [

1,

10].

The variation in allelic frequencies reflects both population structure and the influence of breeding practices. Rare alleles (<1.4% in Eastern, <0.8% in Western populations) indicate the presence of low genetic variants specific to each population, thereby contributing to overall genetic diversity [

30]. Differences between Eastern and Western Arabian horses suggest that Western populations may have undergone selective pressures or historical breeding programs favoring slightly higher allelic frequencies, while maintaining a lower prevalence of private alleles exceeding 0.8%. These patterns highlight population-specific adaptations and underscore the importance of conserving rare alleles to preserve genetic diversity within horse breeds.

Observed and expected heterozygosity values further reflect differences in allele number across loci, confirming substantial genetic diversity in both Eastern and Western Arabian populations. A slight deficit of heterozygosity in Tunisian horses may indicate historical breeding practices or selective pressures that reduced genetic variation. By contrast, higher observed heterozygosity in Syrian non-registered horses and Polish/Shagya Arabians reflects broader genetic backgrounds and less restrictive breeding management [

30]. Western Arabian horses maintain consistently high heterozygosity across loci, whereas Eastern Arabians show greater variation, reflecting localized breeding strategies and potential founder effects. Conserving heterozygosity remains critical to maintaining genetic health and adaptive potential in Arabian horse populations.

Comparable trends were reported in other domestic species, where the relationship between breeding history, heterozygosity levels, and genetic structure was similarly highlighted through microsatellite analyses [

2].

The excess of the observed number of alleles (Na) over the effective number of alleles (Ne) in both Eastern and Western Arabian horses indicates a high level of genetic diversity. Western populations display slightly greater overall diversity, with both observed and expected average allele numbers exceeding those of Eastern horses. Locus-to-locus variation highlights the complex genetic structure unique to each population, likely shaped by historical breeding programs, selective mating strategies, and the introduction of specific lineages over time [

30]. Preserving this genetic diversity is essential for safeguarding adaptive potential and reducing the risk of inbreeding in future breeding programs.

Because relatedness between individuals was not formally tested, deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and some FIS patterns should be interpreted with caution, as undetected in relationships within the lineage groups may contribute to these results.

Fixation index (Fis) results demonstrate further differentiation between populations. In Eastern Arabian horses, the moderately positive mean Fis (0.028) reflects a slight deficit of heterozygotes, consistent with possible inbreeding or selection for homozygotes at certain loci. Conversely, Western Arabians exhibited a slightly negative mean Fis (–0.006), suggesting a subtle excess of heterozygotes and therefore marginally higher genetic diversity. These findings align with previous studies: [

30] reported average Fis values of 0.037 in Syrian non-registered Arabian horses, –0.007 in Syrian registered horses, 0.017 in Iranian Arabians, and 0.028 in Tunisian Arabians. The Eastern population analyzed here shows heterozygosity levels comparable to Tunisian horses, while the Western population resembles Syrian registered horses with a negative fixation index, reflecting greater variability. Locus-specific deviations were also observed, with HMS6 (Eastern) and HMS1 (Western) showing the strongest excess of heterozygotes, whereas LEX3 consistently indicated a heterozygote deficit in both groups. It is important to note that LEX3 is an X-linked marker, and males are hemizygous rather than homozygous. Because sex was not incorporated into the computation of heterozygosity and fixation indices, the observed heterozygote deficit and the high FIT value at this locus may be partly influenced by its sex-linked inheritance pattern. Thus, LEX3-related deviations should be interpreted with caution. These patterns may reflect historical breeding practices, genetic drift, or the presence of null alleles, all of which shape Arabian horse diversity.

Genetic differentiation indices further support these findings. The low FST value (0.011) between Eastern and Western Arabians suggests substantial gene flow and shared ancestry, consistent with their close historical and geographical relationship. In contrast, the higher FST (0.071) observed between Eastern Arabians and Thoroughbreds reflects moderate differentiation, likely driven by distinct breeding histories and selection pressures. The overall average FST of 0.058 indicates moderate genetic differentiation among the three populations, consistent with Wright’s classification [

16]. Similarly, the heterozygosity deficit reflected by the positive average FIT (0.076) suggests some degree of non-random mating or selection for homozygous genotypes, while keeping in mind that the extreme FIT at LEX3 (0.414) is potentially driven by its X-linked nature. Conversely, loci such as HMS6, with negative FIS and FIT values, highlight an excess of heterozygotes, likely resulting from balancing selection or the presence of null alleles.

Genetic distance values further corroborate these patterns. Eastern and Western Arabian horses displayed the smallest distance (0.052), confirming their close relationship and possible historical gene flow, with 94.8% of genes being shared. In contrast, the greatest distance (0.374) was observed between Eastern Arabians and Thoroughbreds, indicating substantial divergence (62.6% similarity), consistent with the closed breeding practices of the latter. An intermediate distance (0.243) between Western Arabians and Thoroughbreds suggests some degree of shared ancestry or historical crossbreeding. Overall, the observed genetic distances are consistent with the FST results, confirming that Arabian subpopulations are more closely related to each other than to Thoroughbreds.

Gene flow (Nm) estimates also support this conclusion. The highest value (0.950) was found between Eastern and Western Arabian horses, confirming their strong genetic connectivity. By contrast, lower values were observed between Eastern Arabians and Thoroughbreds (0.688), reflecting the genetic isolation of the latter, while the intermediate value between Western Arabians and Thoroughbreds (0.784) may be explained by occasional historical introgression or shared ancestral contributions. Collectively, these results indicate that the Western Arabian population has exerted a more pronounced influence on the genetic structure of the Eastern population, whereas Thoroughbreds remain comparatively distinct.

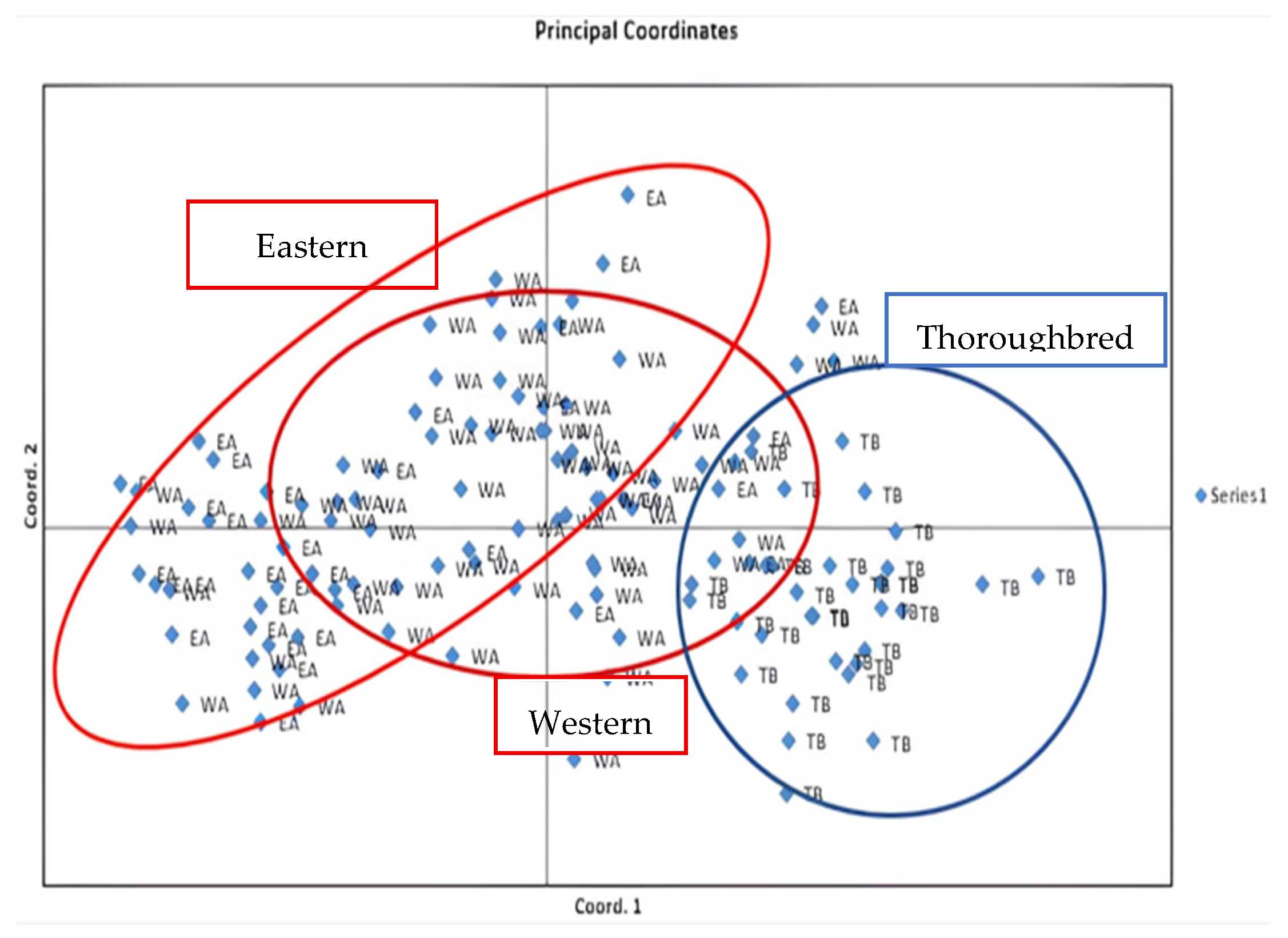

Finally, the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) confirmed the existence of two distinct subpopulations (Eastern and Western) within the Arabian breed, reflecting the impact of specific breeding practices and initial differences in origin on genetic structure. The PCA also revealed strong genetic similarity between the two Arabian subgroups, consistent with historical interbreeding and shared ancestry. In contrast, Thoroughbreds were clearly separated from Eastern Arabians, with only a minority of individuals clustering closer to Western Arabians. This emphasizes both the divergence between Thoroughbreds and Arabians and the occasional genetic contribution of Western Arabians to Thoroughbred populations.