A Protocol-Oriented Scoping Review for Map-First, Auditable Targeting of Orogenic Gold in the West African Craton (WAC): Deferred, Out-of-Sample Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

2. Review Method

2.1. Scope and Sources

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Quantified parameters: Reports dated or measured values (e.g., U-Pb/Sm-Nd/Pb-Pb ages; crustal thickness; LAB depth; strain/kinematic indicators with uncertainties).

- Regional extent: Resolves patterns at belt to craton scale, beyond a single deposit or camp.

- Architecture/kinematics: Constrains three-dimensional architecture or first-order shear-system kinematics relevant to corridor continuity.

- Shield-scale coverage: Results spanning ≥ 1 major shield (Reguibat or Leo–Man) and its nearest craton-margin/basin boundary segment.

- Corridor continuity: Structural or potential-field evidence for ≥100 km along-strike continuity of a corridor-scale shear system.

- Cross-domain transect: A geophysical section (receiver functions/tomography or joint gravity–magnetics) that crosses a domain boundary used later in the synthesis.

2.3. Search Strategy and PRISMA-ScR Reporting

2.3.1. Information Sources and Time Window

2.3.2. Search Strings

2.3.3. Screening and Eligibility

2.3.4. Data Charting and Evidence Classes

2.4. Spatial Scale and Resolution (Verifiability)

- Gravity and magnetics: Effective grid spacing ≤ 10 km after processing; filters (e.g., reduction-to-pole, upward continuation, tilt/total horizontal gradient) must be stated.

- Seismic/RF and tomography: Moho and LAB estimates must include uncertainty bounds; lateral sampling dense enough to resolve domain-scale contrasts referenced in the text.

- Structural mapping: Map scale ≤ 1:500,000 or lineament products derived from national/regional surveys, sufficient to link first-order corridors to second-order dilational sites (bends, step-overs, relays).

2.5. Evidence Weighting

- B1.

- Datasets and splits. Assemble (i) a training set of belts/segments with vetted orogenic gold positives and negatives; (ii) a blind, inter-belt test set at country scale; and (iii) the map layers used here (total horizontal gradient (THG) ridges, reduced-to-pole (RTP)/tilt products, Moho/LAB surfaces, lineament fields) at the resolutions stated in Section 2.3. No datasets are distributed or curated in this paper.

- B2.

- Null models. Adopt two baselines: (a) Complete Spatial Randomness (CSR) within surveyed corridors; and (b) structure-aware nulls that preserve first-order corridor geometry while randomizing second-order features (e.g., jogs/relays). These define the expected by-chance enrichment near long linear features.

- B3.

- Performance metrics. For each criterion and their combinations, compute odds ratios (with Wald intervals), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and precision–recall (PR) curves, and report area under the ROC curve (AUC) and area under the precision–recall curve (AUPRC) with bootstrap uncertainty. The blind set is reserved strictly for evaluation.

- B4.

- Threshold optimization. Using training data only, derive operational cut-offs via Youden’s J (ROC) and F1 (PR). Freeze these cut-offs and report performance on the blind set. Present provisional (this paper) and calibrated (future) values side-by-side.

- B5.

- Sensitivity and ablation. Vary grid spacing, filters (RTP/tilt/upward continuation), and corridor extraction to assess threshold stability. Apply ablation (removing one criterion at a time) to quantify each indicator’s marginal contribution.

- B6.

- Uncertainty propagation. Propagate Moho/LAB and corridor-mapping uncertainties using Monte Carlo perturbations and document any go/hold or ESG-based no-go decision flips induced by threshold jitter.

2.6. Conflict Resolution and Traceability

- LAB depth vs. corridor geometry: When tomography and receiver function estimates of LAB differ by >20 km along a mapped first-order corridor, both surfaces are retained. Preference is given to the surface that better predicts (i) maxima in gravity-gradient magnitude and (ii) corridor-parallel lineament density evaluated in subsequent sections.

- Through-going shear vs. segmented step-overs: Where structural mapping infers a continuous strike-slip corridor, but potential-field data indicate segmentation, both kinematic options are carried forward. The preferred scenario is the one that best matches deposit clustering and independently mapped dilational sites.

- Chronology mismatches: When age populations defining deformation stages (e.g., D1–D3) overlap within analytical uncertainty, the most conservative interpretation is adopted (broader time window), and stage assignment is tied to kinematic indicators rather than ages alone.

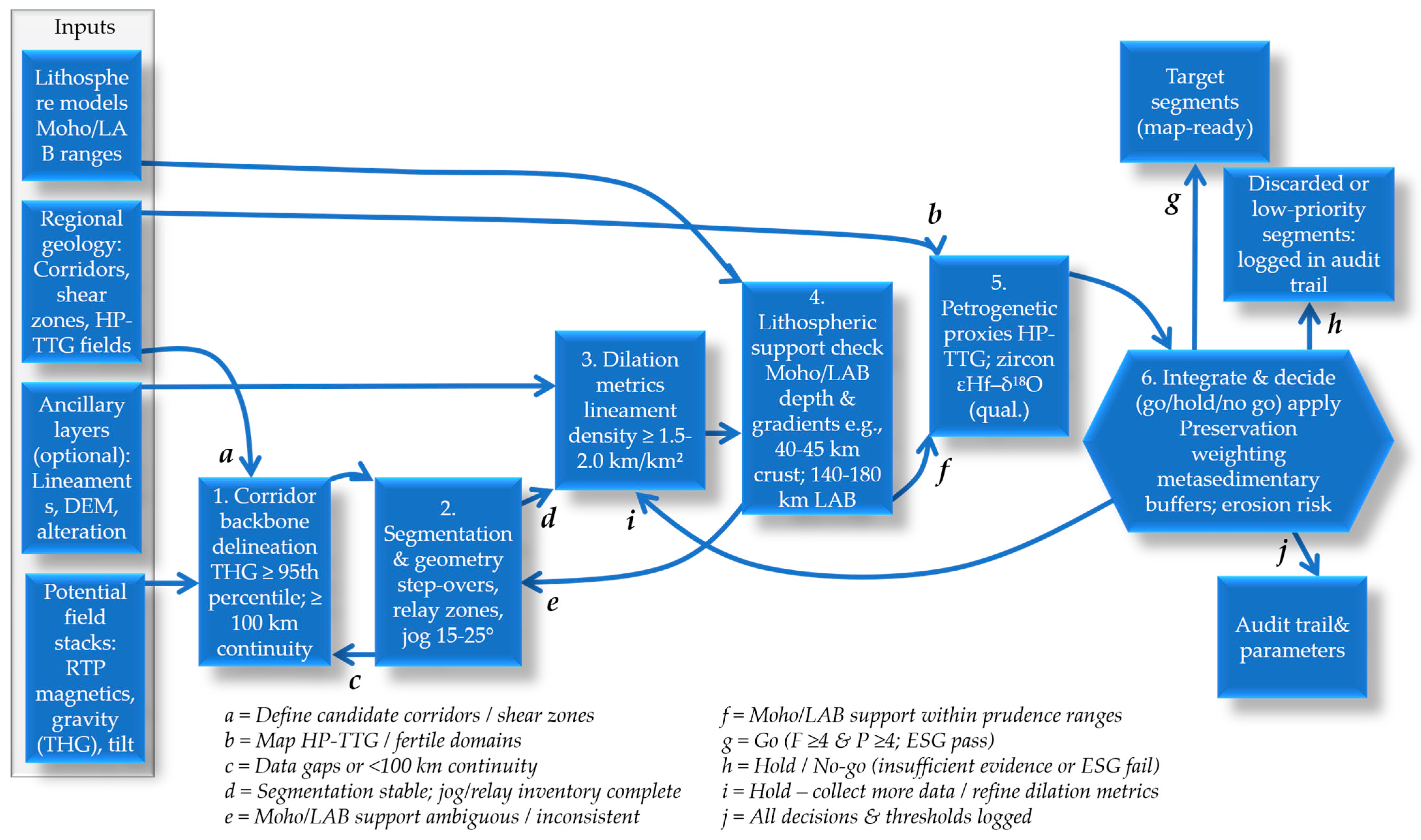

2.7. Workflow

2.8. Deferred Evaluation Protocol (No New Data Used)

2.8.1. Test-Area Selection (A Priori)

2.8.2. Minimal Compilation (Suggested Public Sources)

2.8.3. Analysis Steps

2.8.4. Sensitivity and Uncertainty

2.8.5. Success/Failure Criteria and Reporting

2.9. Methodological Contributions

2.10. Reproducibility and Audit Log

3. State of Knowledge and Evidence Synthesis for the West African Craton

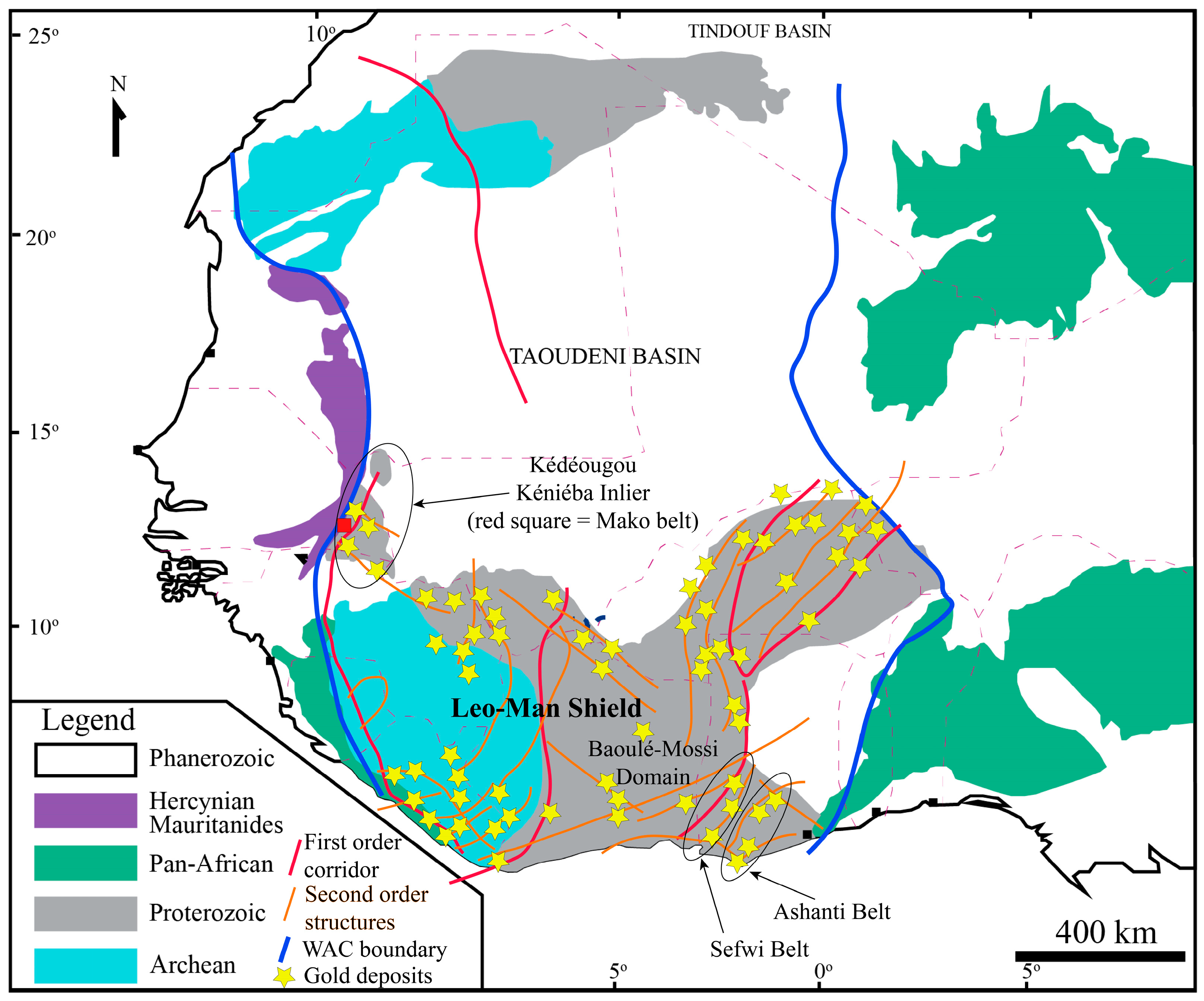

3.1. Geological and Structural Overview of the West African Craton (WAC)

3.1.1. Aim and Framework

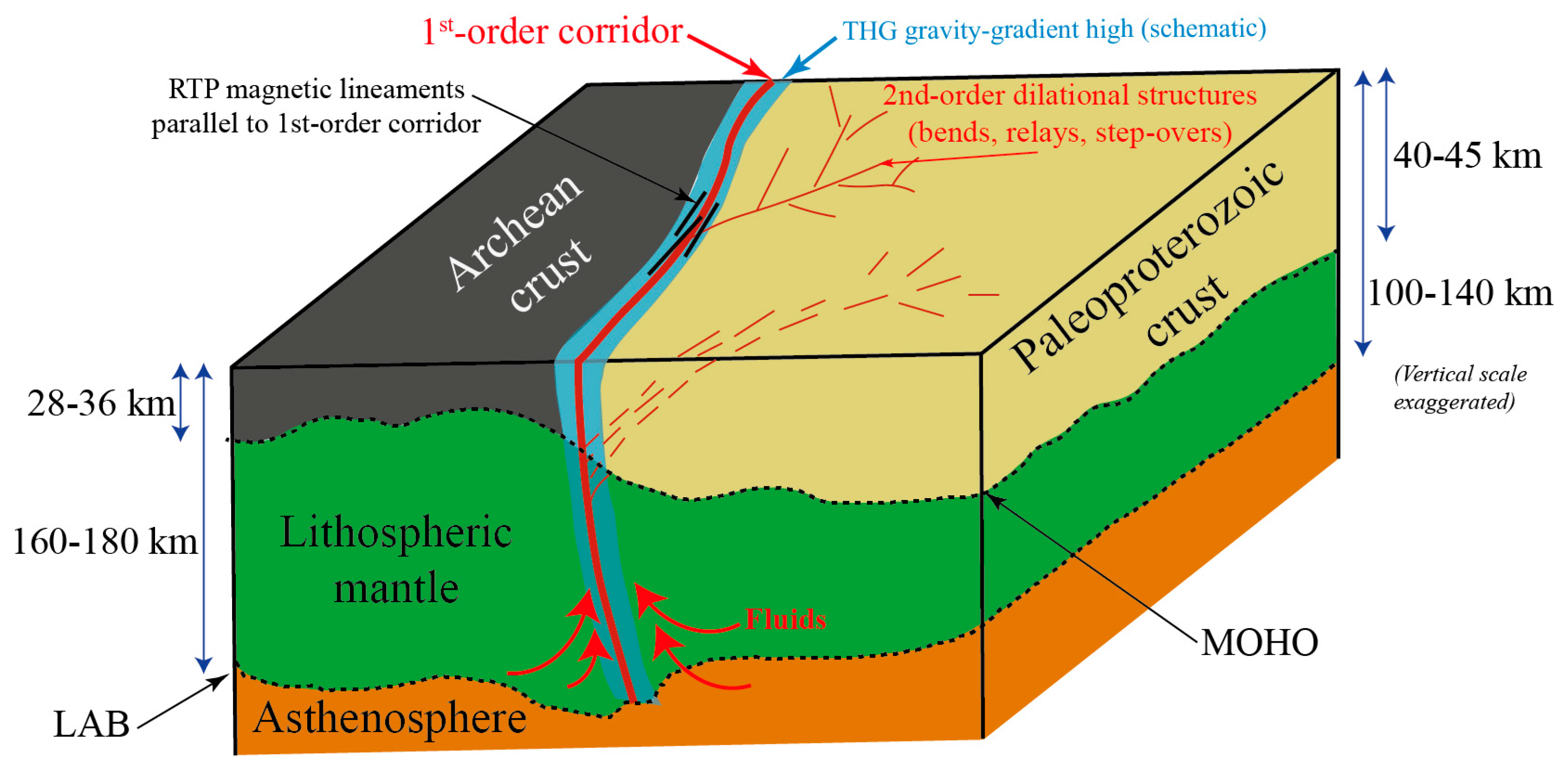

3.1.2. Craton-Scale Architecture: Domains, Boundaries, and Segmentation

3.1.3. Hierarchy of Shear Systems: First-Order Corridors Vs. Second-Order Dilation Sites

3.1.4. Belt-Scale Case Studies: Ashanti vs. Sefwi

3.1.5. Synthesis and Implications

3.2. Geochronology

3.2.1. Overview and Datasets

3.2.2. Archean Inheritance and Early Foundations

3.2.3. Birimian Crustal Growth (ca. 2.30–2.10 Ga)

3.2.4. Eburnean Windows and Reactivations: Timing, Bounds, and Uncertainties

- Onset and peak deformation-metamorphism (ca. 2.10–1.98 Ga). U-Pb zircon/monazite ages from amphibolite-granulite facies rocks and syn-kinematic granitoids cluster shortly after 2.10 Ga, with many belts registering peak metamorphic conditions near or just below 2.00 Ga [28,29,30]. Typical analytical uncertainties (2σ) are ±3–10 Ma for zircon/monazite and larger for whole-rock systems.

- Sustained high-T residence and late plutonism (ca. 1.98–1.90 Ga). High-temperature residence and post-collisional granitoid emplacement persist into the 1.98–1.90 Ga interval, reflecting thermal relaxation and local anatexis following crustal thickening [4].

- Localized reactivations (≤1.90 Ga). Later brittle–ductile reworking is locally recorded and best constrained where structural–metamorphic observations are paired with new U-Pb datasets at belt scale; we carry such “reactivation flags” into the structural synthesis to test linkages with corridor segmentation [4,29,30].

3.2.5. Juvenile vs. Recycled Contributions: Coupled Isotopic and Trace-Element Diagnostics

- Zircon εHf-δ18O coupling (detrital and magmatic). Positive εHf(t) combined with mantle-like δ18O values indicates dominantly mantle-derived melts, whereas sub-mantle δ18O or subdued εHf trends suggest variable crustal re-melting or assimilation [18]. We compile available Birimian detrital–zircon datasets and propagate their uncertainties into belt-level summaries [4].

- Arc-affinity pressure proxies in TTG and andesitic suites (Sr/Y-La/Yb). Elevated Sr/Y at given La/Yb ratios is interpreted to reflect residual garnet and/or amphibole (deep crustal thickening), whereas lower Sr/Y at comparable La/Yb is consistent with shallower melting and/or greater plagioclase stability; in combination with εHf-δ18O, these trends help separate juvenile thickened-arc additions from crustal reworking [18,21].

3.2.6. Synthesis

3.3. Geophysical Data Synthesis

3.3.1. Overview of Geophysical Techniques Applied to the WAC

3.3.2. Crust and LAB Structure (Thickness Ranges, Domain Contrasts, Uncertainties)

3.3.3. Gravity Anomalies and Domain/Corridor Boundaries

3.3.4. Magnetic Lineaments, Relays, and Jogs (Map-Scale Kinematic Proxies)

3.3.5. Integrated 3D Framework (Crust-LAB-∇G-Lineaments-Corridors)

3.4. Geochemical and Petrological Characteristics

3.4.1. TTG Diagnostics and Tectonic Inference

3.4.2. Greenstones: Arc Vs. Back-Arc Discrimination and Fertility Implications

3.4.3. Metasediments, Fluid–Rock Interaction, and Redox Buffering

3.5. Critical Appraisal of Prior Work

4. Discussion

4.1. Tectonic-Metallogenic Synthesis

4.1.1. Predictive Rules (with Measurable Thresholds)

- P1—Corridor-focused clustering along gravity-gradient ridges.

- P2—Magnetic-lineament density and jog frequency as proxies for second-order dilation.

- P3—Thickness contrasts (Moho/LAB) predict corridor robustness.

- P4—TTG pressure proxies forecast “Fertility corridors.”

- P5—Juvenile vs. recycled source fingerprints modulate trap efficiency.

4.1.2. Mechanistic Integration

- Strain-driven permeability cycling. Jog/relay geometries within corridor cores promote transient dilation and episodic overpressure, producing crack-seal vein arrays that scale with lineament density and jog angles [31,39,40]. This explains the P2 association between high-density lineament fields and broader alteration footprints.

- Redox and sulfur speciation controls. Where corridors intersect carbonaceous/Fe-rich metasediments, fluids experience redox buffering and sulfur-speciation shifts that trigger efficient gold precipitation; broader halos in Ashanti relative to Sefwi reflect stronger buffering and sustained fluid throughput [3,13,41,53,54]. This ties P1–P2 spatial predictors to the chemical efficiency of traps.

- Source-pathway coupling. High-pressure TTG fields (P4) and juvenile isotopic fingerprints (P5) are consistent with thickened-arc melting and elevated fluid budgets, respectively; their co-location with THG-defined backbones enhances both pathway robustness and precipitation efficiency, reconciling structural predictors with geochemical outcomes [4,15,16,17,18,19].

4.2. Tectonic Evolution and Geodynamic Model

4.2.1. Stage I—Juvenile Arc Assembly and Early Basin Formation (ca. 2.30–2.20 Ga)

4.2.2. Stage II—Thickening, Transpression, and Collision (ca. 2.20–2.05 Ga)

- Corridor robustness: Deposit clusters within ±15 km of corridor backbones where THG ≥ 95th percentile over ≥100 km strike [4,11]. These thresholds must be empirically calibrated and reported with effect sizes and uncertainty; without this, the checklist risks encoding expert priors rather than a demonstrable predictive signal.

4.2.3. Stage III—Strain Localization, Transcurrent Partitioning, and Peak Metamorphism (ca. 2.05–1.98 Ga)

4.2.4. Stage IV—Thermal Relaxation, Late Plutonism, and Localized Reactivation (ca. 1.98–1.90 Ga)

4.2.5. Synthesis and Usage

4.3. Metallogenic Implications of the Tectonic Model

4.3.1. Distinguishing Fertility from Preservation (Operational Criteria and Thresholds)

4.3.2. A Six-Step, Go/Hold/No-Go Workflow

- Step 1—Delineate first-order corridors (go if ≥1 hit). Map THG ≥ 95th percentile ridges continuous for ≥100 km and quantify distance buffers (±15 km). The ≥95th-percentile, ±15 km buffer, and ≥100 km continuity values are placeholders to standardize auditing across maps. They must be calibrated with the protocol described in Section 2.7 (ROC/PR, OR vs. CSR) before being treated as performance-backed cut-offs. Until then, use them strictly as triage heuristics and report decisions with their associated uncertainty. Example: Ashanti backbone meets both criteria; parts of Sefwi fall below continuity thresholds [4,9,11].

- Step 2—Extract second-order dilation metrics (go if ≥2 hits). Compute lineament density, jog angle, and relay length from RTP/tilt stacks; flag cells with ≥1.5–2.0 km km−2, 15–25°, 2–8 km. The 1.5–2.0 km km−2, 15–25°, and 2–8 km ranges are non-calibrated default bands drawn from prior case studies and are intended only to make the workflow auditable. Their eventual operational values should be selected using Section 2.7 (threshold optimization on training belts, locked, and then reported on blind belts), with sensitivity to grid size and filter set. Ashanti commonly passes; Sefwi passes sporadically [10,13,31].

- Step 5—Evaluate fluid–rock and redox context (go if ≥2 hits). Confirm preserved metasedimentary buffers (carbonaceous/Fe-rich units), broad halos (≥500–1000 m), and crack-seal/fault-valve textures near dilation sites. Ashanti commonly meets all; Sefwi tends to show ≤200–400 m halos with localized high-grade shoots [3,13,39,40,41,53,54].

- Step 6—Integrate and decide (go if total ≥ 4 criteria across Steps 1–5). Sum hits across the checklist; segments with ≥4 proceed to detailed targeting (orientation analyses, prospect-scale mapping) (see Supplementary Table S1). Segments with <4 criteria are classified as hold (deferred or dropped pending low-cost confirmation). As for the other numeric thresholds in this paper, the “≥4 criteria” cut-off is a non-calibrated default used here only to standardize auditing and reporting; its eventual operational value must be optimized using the protocol in Section 2.7 before being treated as a performance-backed decision rule. Apply Preservation weighting where late reactivation or denudation is evident [4,11].

4.3.3. Operational Impact for Mining: Exploration Decision Support

- Rationale and scope

- Decision rule and sequencing

- Qualitative program-scale implications

- A more focused scout-drilling program (fewer low-prospectivity segments advanced simply because they are logistically easy);

- Atendency towards a smaller surface footprint than for a naïve grid- or traverse-based drilling strategy with similar budgets; and

- A more explicit linkage between geological arguments and ESG/Permitting considerations.

- Environmental and capital expenditure (CAPEX) considerations (qualitative only)

- Identify where drilling is most justifiable per unit of disturbance and investment; and

- Make explicit, recorded trade-offs when programs choose to drill segments that underperform on Fertility–Preservation or ESG criteria (for example, to test a new concept or secure tenure).

- Implementation guidance:

- Preserve the checklist threshold and criteria as written at the time of program design and document any subsequent changes;

- Maintain a machine-readable audit log of all scoring decisions, including which segments were advanced, held, or rejected at each step of the workflow;

- Record, for each drill-tested segment, whether it belonged to the go ∩ ESG-pass set or required an explicit override; and

- Keep exploration cost and disturbance metrics (e.g., platforms deployed, meters drilled, internal CO2e estimates where available) separate from the scientific checklist until a blinded, out-of-sample evaluation is performed.

- Conclusion

4.4. Gaps and Future Research Directions

4.4.1. Joint RF-Gravity–Magnetics Inversions

- Objective: Resolve whether first-order shear corridors are systematically rooted on crust/LAB steps or only coincide with them.

- Approach: Conduct joint inversions integrating receiver functions (Moho), surface-wave tomography (LAB), and potential fields (Bouguer + total horizontal gradient, magnetic RTP/tilt) to co-estimate density/velocity contrasts and their uncertainties. This extends existing craton-scale models to corridor-resolving grids (≤10 km), with standardized processing logs (filters, upward continuation, reduction-to-pole).

- Sampling plan (WAC): Three transects per shield: (i) southern Leo–Man across Ashanti and Sefwi; (ii) Kedougou-Kéniéba (Mako belt) into the craton margin; and (iii) western Reguibat margin.

- Key outputs: Probability maps that the THG ≥ 95th-percentile ridges coincide with Moho/LAB gradients exceeding set thresholds; effect sizes linking thickness contrasts to corridor straightness/segmentation.

4.4.2. Coupled Zircon εHf-δ18O Transects: Juvenile vs. Recycled Sources

- Objective. Test whether corridor segments flagged as “fertile” by structural–geophysical criteria also record juvenile mantle addition (positive εHf(t), mantle-like δ18O) vs. segments dominated by crustal recycling.

- Approach: Acquire detrital and magmatic zircon from granitoids and volcano sedimentary units along and across corridors; analyze εHf(t) and δ18O on the same grains, propagate 2σ uncertainties, and compare with TTG Sr/Y-La/Yb-Eu/Eu* proxies.

- Sampling plan (WAC): Paired corridors and off-corridor controls in Ashanti, Sefwi, Mako, and Baoulé-Mossi interiors; ≥50–100 zircon spots per site to stabilize kernel estimates.

- Key outputs. Spatial covariation of εHf-δ18O classes with alteration-halo breadth and camp density; odds ratios quantifying predictive gain beyond structure alone.

4.4.3. Paleostress and Dilation Geometry Calibration

- Objective: Discriminate between through-going strike-slip vs. segmented step-over kinematics and quantify the fault-valve/crack-seal cycle that links second-order dilation to ore shoots.

- Approach: Compile oriented vein/cleavage/σ1-σ3 indicators, jog angles, relay lengths, and vein-swarm statistics; integrate microstructural evidence for crack-seal and episodic overpressure with mapped magnetic lineaments and THG ridges.

- Sampling plan (WAC): High-resolution structural datasets in Ashanti (broad halos, dense jogs) and Sefwi (narrow halos, fewer jogs), plus targeted districts in Mako where dilation loci are well expressed.

- Key outputs: Calibrated ranges for jog angle (15–25° fertile vs. 5–15° less fertile) and relay length (2–8 km vs. ≤3–5 km) tied to vein intensity, alteration width, and deposit continuity.

4.5. Limitations and Outlook

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| AUPRC | Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve |

| CSR | Complete Spatial Randomness |

| LAB | Lithosphere–Asthenosphere Boundary |

| MPC | Mafic Proto-Crust |

| RF | Receiver Functions |

| RTP | Reduction-to-the-Pole |

| THG | Total Horizontal Gravity Gradient |

| WAC | West African Craton |

Appendix A

Reproducible Mini-Demonstration of the Targeting Checklist (Toy Belt Segment)

- Objective

- 2.

- Data and Test Area

- Sites: 12 synthetic locations (S01–S12) along a stylized belt segment.

- Ground-truth: Known occurrence/prospect (1) vs. unknown/negative (0).

- Variables (typical for orogenic gold):

- ○

- THG_percentile (0–100) as a proxy for tectono-hydrothermal intensity;

- ○

- Lineament density (km/km2);

- ○

- Jog angle (degrees; compressional/transpressional “sweet spot”);

- ○

- Distance to TTG/tonalite contact (km);

- ○

- Sr/Y (Fertility proxy).

- 3.

- Method (Checklist → Score)

- Pass/fail rules (default placeholders; replace during real calibration):

- ○

- THG_percentile ≥ 95 → Pass

- ○

- Lineament density ≥ 1.8 km/km2 → Pass

- ○

- Jog angle 15–25° → Pass

- ○

- Distance to TTG ≤ 5 km → Pass

- ○

- Sr/Y ≥ 30 → Pass

- Composite score: Unweighted sum of passes (0–5), normalized to [0, 1] for ranking.

- Evaluation (toy): Compute the ROC curve (TPR vs. FPR) using the normalized score against the ground-truth labels.

- Good practice (real use): Sensitivity checks, ablations, and district-specific threshold calibration.

- 4.

- Interpretation

- Even with default, uncalibrated thresholds, the checklist partly separates positives from negatives (toy AUC > 0.5).

- The composite score provides a practical ranking for follow-up.

- Compensation among criteria (e.g., excellent proximity to TTG vs. sub-optimal jog angle) motivates ablation tests and interaction checks during calibration.

- 5.

- Reproducibility

- What to include: See Supplementary Tables.

- Minimal workflow (for a real belt segment): Populate the table with public layers (lineaments, lithological contacts, Sr/Y or proxies), apply default or district-specific thresholds, compare against known occurrences, then compute ROC/PR and run small sensitivity analyses (±10–20% on thresholds).

- 6.

- Limitations and Intended Use

- This is a demonstration, not a claim of calibrated discovery probability.

- Thresholds are initial values and must be calibrated by district.

- Performance (AUC) is a ranking utility, not a discovery forecast.

- Main text should discuss uncertainties (e.g., Moho/LAB geometry, lineament quality, grid resolution) and provide a source-audit grid.

References

- Celli, N.L.; Lebedev, S.; Schaeffer, A.J.; Gaina, C. African cratonic lithosphere carved by mantle plumes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessoles, B. Géologie de l’Afrique. Vol 1: Le Craton Ouest Africain. Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières. Mémoire 1977, 88, 402. [Google Scholar]

- Milési, J.P.; Ledru, P.; Feybesse, J.L.; Dommanget, A.; Marcoux, E. Early Proterozoic ore deposits and tectonics of the Birimian orogenic belt, West Africa. Precambrian Res. 1992, 58, 305–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessell, M.W.; Begg, G.C.; Miller, M.S. The geophysical signatures of the West African Craton. Precambrian Res. 2016, 274, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Pape, F.; Jones, A.G.; Jessell, M.W.; Hogg, C.; Siebenaller, L.; Perrouty, S.; Touré, A.; Ouiya, P.; Boren, G. The nature of the southern West African craton lithosphere inferred from its electrical resistivity. Precambrian Res. 2021, 358, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, G.C.; Griffin, W.L.; Natapov, L.M.; O’Reilly, S.Y.; Grand, S.P.; Ryan, C.G.; Hronsky, J.M.A. The Lithospheric Architecture of Africa: Seismic Tomography, Mantle Petrology, and Tectonic Evolution. Geosphere 2009, 5, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishwick, S.; Bastow, I.D. Towards a better understanding of African topography: A review of passive-source seismic studies of the African crust and upper mantle. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2011, 357, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, A.J.; Lebedev, S. Global shear speed structure of the upper mantle and transition zone. Geophys. J. Int. 2013, 194, 417–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasyanos, M.E.; Masters, T.G.; Laske, G.; Ma, Z. LITHO1.0: An updated crust and lithospheric model of the Earth. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2014, 119, 2153–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesur, V.; Hamoudi, M.; Choi, Y.; Dyment, J.; Thébault, E. Building the second version of the world digital magnetic anomaly map (WDMAM). Earth Planets Space 2016, 68, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, R.J.; André-Mayer, A.S.; Jowitt, S.M.; Mudd, G.M. West Africa: The world’s premier Paleoproterozoic gold province. Econ. Geol. 2017, 112, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, P.; Ebbing, J.; Celli, N.L.; Rey, P.F. Two-step gravity inversion reveals variable architecture of African cratons. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 696674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrouty, S.; Aillères, L.; Jessell, M.W.; Baratoux, L.; Bourassa, Y.; Crawford, B. Revised Eburnean geodynamic evolution of the gold-rich southern Ashanti Belt, Ghana, with new field and geophysical evidence of pre-Tarkwaian deformations. Precambrian Res. 2012, 204, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Herwaarden, D.-P.; Thrastarson, S.; Hapla, V.; Afanasiev, M.; Trampert, J.; Fichtner, A. Full-waveform tomography of the African Plate using dynamic mini-batches. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2023, 128, e2022JB026023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H. The Archean grey gneisses and the genesis of continental crust. In Developments in Precambrian Geology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; Volume 11, pp. 205–259. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, S.; Tiepolo, M.; Vannucci, R. Growth of early continental crust controlled by melting of amphibolite in subduction zones. Nature 2002, 417, 837–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumbia, S.; Pouclet, A.; Kouamelan, A.; Peucat, J.J.; Vidal, M.; Delor, C. Petrogenesis of juvenile-type Birimian (Paleoproterozoic) granitoids in Central Côte-d’Ivoire, West Africa: Geochemistry and geochronology. Precambrian Res. 1998, 87, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.M.W.; Spencer, C.J. The zircon archive of continent formation through time. In Continent Formation Through Time; Roberts, N.M.W., van Kranendonk, M.J., Parman, S.W., Shirey, S.B., Clift, P.D., Eds.; Geological Society, London, Special Publications: London, UK, 2015; Volume 389, pp. 197–225. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, J.L.; McInerney, D.J.; Barovich, K.M.; Kirkland, C.L.; Pearson, N.J.; Hand, M. Strengths and limitations of zircon Lu-Hf and O isotopes in modelling crustal growth. Lithos 2016, 248–251, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Avila, L.A.; Belousova, E.; Fiorentini, M.L.; Eglinger, A.; Block, S.; Miller, J. Zircon Hf and O-isotope constraints on the evolution of the Paleoproterozoic Baoulé-Mossi domain of the southern West African Craton. Precambrian Res. 2018, 306, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratoux, L.; Metelka, V.; Naba, S.; Jessell, M.W.; Grégoire, M.; Ganne, J. Juvenile Paleoproterozoic crust evolution during the Eburnean orogeny (~2.2–2.0 Ga), western Burkina Faso. Precambrian Res. 2011, 191, 18–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouchami, W.; Boher, M.; Michard, A.; Albarede, F. A Major 2.1 Ga Event of Mafic Magmatism in West Africa: An Early Stage of Crustal Accretion. J. Geophys. Res. 1990, 95, 17605–17629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boher, M.; Abouchami, W.; Michard, A.; Albarede, F.; Arndt, N.T. Crustal Growth in West Africa at 2.1 Ga. J. Geophys. Res. 1992, 97, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirdes, W.; Davis, D.W. U-Pb geochronology of Paleoproterozoic rocks in the southern part of the Kedougou-Kenieba Inlier, Senegal, West Africa: Evidence for diachronous accretionary development of the Eburnean province. Precambrian Res. 2002, 118, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenholm, M. The global tectonic context of the ca. 2.27–1.96 Ga Birimian Orogen-Insights from comparative studies, with implications for supercontinent cycles. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 193, 260–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Avila, L.A.; Kemp, A.I.; Fiorentini, M.L.; Belousova, E.; Baratoux, L.; Block, S.; Jessell, M.; Bruguier, O.; Begg, G.C.; Miller, J.; et al. The geochronological evolution of the Paleoproterozoic Baoulé-Mossi domain of the southern West African Craton. Precambrian Res. 2017, 300, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Avila, L.A.; Baratoux, L.; Eglinger, A.; Fiorentini, M.L.; Block, S. The Eburnean magmatic evolution across the Baoulé-Mossi domain: Geodynamic implications for the West African Craton. Precambrian Res. 2019, 332, 105392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledru, P.; Pons, J.; Milési, J.P.; Feybesse, J.L.; Johan, V. Transcurrent tectonics and polycyclic evolution in the Lower Proterozoic of Senegal-Mali. Precambrian Res. 1991, 50, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, K.A. Succession of structural events in the Goren greenstone belt (Burkina Faso): Implications for West African tectonics. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2010, 56, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lompo, M. Paleoproterozoic structural evolution of the Man-Leo Shield (West Africa). Key structures for vertical to transcurrent tectonics. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2010, 58, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunks, A.J.; Selley, D.; Rogers, J.R.; Brabham, G. Vein mineralization at the Damang Gold Mine, Ghana: Controls on mineralization. J. Struct. Geol. 2004, 26, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, N.-P.; Kaban, M.K.; Tesauro, M.; Mooney, W.D.; Thomas, M. A thermo-compositional model of the African cratonic lithosphere. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2022, 23, e2021GC010296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugboji, T.; Xue, S.; Legre, J.-J.; Tamama, Y. Africa’s crustal architecture inferred from probabilistic and perturbational inversion of ambient noise: ADAMA. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2024, 25, e2023GC011086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosso Téguia Moussé, E.E.; Ebbing, J.; Haas, P.; Szwillus, W. Integrated geophysical-petrological 3D-modeling of the West and Central African Rift System and its adjoining areas. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2024, 129, e2024JB029226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessell, M.; Liégeois, J.-P. 100 years of research on the West African Craton. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2015, 112 Pt B, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markwitz, V.; Hein, K.A.A.; Jessell, M.W.; Miller, J. Metallogenic portfolio of the West Africa craton. Ore Geol. Rev. 2016, 78, 558–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenholm, M.; Jessell, M.; Thébaud, N. A geodynamic model for the Paleoproterozoic (ca. 2.27–1.96 Ga) Birimian Orogen of the southern West African Craton-Insights into an evolving accretionary-collisional orogenic system. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 192, 138–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardon, D.; Berger, J.; Martellozzo, F. Archean craton assembly and Paleoproterozoic accretion-collision tectonics in the Reguibat Shield, West African Craton. Precambrian Res. 2024, 413, 107570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bons, P.D.; Elburg, M.A.; Gomez-Rivas, E. A review of the formation of tectonic veins and their microstructures. J. Struct. Geol. 2012, 43, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.F. Injection-driven swarm seismicity and permeability enhancement: Implications for the dynamics of hydrothermal ore systems in high fluid-flux, overpressured faulting regimes-An invited paper. Econ. Geol. 2016, 111, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béziat, D.; Dubois, M.; Debat, P.; Nikiéma, S.; Salvi, S.; Tollon, F. Gold metallogeny in the birimian craton of Burkina Faso (West Africa). J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2008, 50, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, R.A.I.; Ilboudo, H.; Baratoux, D. Structural controls of the expansion of small-scale artisanal gold of Bouda area (Kaya-Goren Green Belt, Burkina Faso) from remote sensing. Earth Space Sci. 2024, 11, e2023EA003217. [Google Scholar]

- Guéye, M.; van den Kerkhof, A.M.; Hein, U.F.; Diène, M.; Muecke, A.; Siegesmund, S. Structural control, fluid inclusions and cathodoluminescence studies of Birimian gold-bearing quartz vein systems in the Paleoproterozoic Mako belt, southeastern Senegal. S. Afr. J. Geol. 2013, 116, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranov, A.; Tenzer, R.; Eitel Kemgang Ghomsi, F. A new Moho map of the African continent from seismic, topographic, and tectonic data. Gondwana Res. 2023, 124, 218–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, D.I.; Goldfarb, R.J.; Gebre-Mariam, M.; Hagemann, S.G.; Robert, F. Orogenic gold deposits: A proposed classification in the context of their crustal distribution and relationship to other gold deposit types. Ore Geol. Rev. 1998, 13, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, D.I.; Goldfarb, R.J.; Robert, F.; Hart, C.J. Gold deposits in metamorphic belts: Overview of current understanding, outstanding problems, future research, and exploration significance. Econ. Geol. 2003, 98, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Blichert-Toft, J.; Arndt, N.T.; Ludden, J.N. Precambrian alkaline magmatism. Lithos 1996, 37, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Avila, L.A.; Belousova, E.; Fiorentini, M.L.; Baratoux, L.; Davis, J.; Miller, J.; McCuaig, T.C. Crustal evolution of the Paleoproterozoic Birimian terranes of the Baoulé-Mossi domain, southern West African Craton: U-Pb and Hf-isotope studies of detrital zircons. Precambrian Res. 2016, 274, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, M.; Ashwal, L.D. Greenstone Belts; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 608–619. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvester, P.J.; Attoh, K. Lithostratigraphy and composition of 2.1 Ga greenstone belts of the West African Craton and their bearing on crustal evolution and the Archean-Proterozoic boundary. J. Geol. 1992, 100, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feybesse, J.L.; Milési, J.P. The Archaean/Proterozoic contact zone in West Africa: A mountain belt of décollement thrusting and folding on a continental margin related to 2.1 Ga convergence of Archaean cratons? Precambrian Res. 1994, 69, 199–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkins, A.G. On the source of orogenic gold. Geology 2013, 41, 1255–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaboury, D. Parameters for the formation of orogenic gold deposits. Appl. Earth Sci. 2019, 128, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedla, G.E.; van der Meijde, M.; Nyblade, A.A.; van der Meer, F.D. A crustal thickness map of Africa derived from a global gravity field model using Euler deconvolution. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 187, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villeneuve, M.; Rossignol, C. Linking the Neoproterozoic to Early Paleozoic belts bordering the West African and Amazonian cratons: Review and new hypothesis. Minerals 2024, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakyi, P.A.; Addae, R.A.; Su, B.X.; Dampare, S.B.; Abitty, E.; Su, B.C.; Liu, B.; Asiedu, D.K. Petrology and geochemistry of TTG and K-rich Paleoproterozoic Birimian granitoids of the West African Craton (Ghana): Petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Precambrian Res. 2020, 336, 105492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, A.; Scherstén, A.; Kemp, A.I.S.; Kristinsdóttir, B.; Kalvig, P.; Anum, S. Zircon U-Pb-Hf evidence for subduction related crustal growth and reworking of Archaean crust within the Palaeoproterozoic Birimian terrane, West African Craton, SE Ghana. Precambrian Res. 2016, 275, 286–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traoré, K.; Chardon, D.; Naba, S.; Wane, O.; Bouaré, M.L. Paleoproterozoic collision tectonics in West Africa: Insights into the geodynamics of continental growth. Precambrian Res. 2022, 376, 106692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersson, A.; Scherstén, A.; Kristinsdóttir, B.; Kemp, A.I.S.; Whitehouse, M.J. Birimian crustal growth in the West African Craton: U-Pb, O and Lu-Hf isotope constraints from detrital zircon in major rivers. Chem. Geol. 2018, 479, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, S.; Baratoux, L.; Zeh, A.; Laurent, O.; Bruguier, O.; Jessell, M.; Ailleres, L.; Sagna, R.; Parra-Avila, L.A.; Bosch, D. Paleoproterozoic juvenile crust formation and stabilisation in the south-eastern West African Craton (Ghana): New insights from U-Pb-Hf zircon data and geochemistry. Precambrian Res. 2016, 287, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predictor | Metric | Threshold (Pass/Fail) | Scale | Primary Dataset/Method | Uncertainty/Notes | Key Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravity-defined corridors | Total horizontal gravity gradient (THG) percentile | ≥95th percentile (corridor cores); ridge continuity ≥ 100 km | Craton/Belt | RTP Bouguer + THG (upward continuation, consistent filters) | Document filters and grid spacing (≤10 km). Edge effects near survey boundaries. | [4,5] |

| Gravity-defined corridors | Distance to corridor backbone | Deposit clusters within ±15 km | Belt/District | THG ridges vs. camp centroids | Use great-circle distances; report kernel bandwidths. | [4] |

| Magnetic lineaments | Lineament density (km/km2) | Fertile: ≥1.5–2.0 (Ashanti-like); less fertile: ≤1.0–1.5 (Sefwi-like) | Belt/District | RTP/tilt/analytic signal lineament stacks | Normalize by map window; exclude cultural noise. | [10,13] |

| Magnetic lineaments | Preferred azimuth dispersion | Corridor-parallel fabric dominant (low circular variance) | Belt | Rose diagrams from lineament vectors | State bin size and smoothing. | [13] |

| Geometric dilation loci | Jog angle (°) | Fertile: 15–25°; less fertile: 5–15° | District | Mapped jogs from magnetics + geology | Measure at consistent scale (1:50–100 k). | [4,31] |

| Geometric dilation loci | Relay length (km) | Fertile: 2–8 km; less fertile: ≤3–5 km | District | Relay analysis along corridor | Report overlap/spacing with uncertainties. | [31] |

| Crustal structure | Crustal thickness (Moho) | Corridor-adjacent: 40–45 km vs. margins: 28–36 km | Craton/Belt | Receiver functions/joint inversions | Moho uncertainty ± 3–6 km (2σ); report station spacing. | [7,8] |

| Lithospheric structure | LAB depth | Corridor-adjacent: 140–180 km vs. margins: 100–120 km | Craton/Belt | Surface-wave tomography/joint models | LAB uncertainty ± 10–20 km; path coverage limits. | [8,9] |

| TTG pressure proxies | Sr/Y; La/YbN; Eu/Eu* | Deep melting: Sr/Y ≥ 40–60; La/YbN ≥ 20–30; Eu/Eu* ≥ 1.05–1.15 | Belt | Whole-rock geochemistry of granitoids | Use consistent normalization; screen alteration. | [15,16,17] |

| Isotopic fingerprints | Zircon εHf(t) & δ18O | Juvenile: εHf(t) > 0 and mantle-like δ18O (~5.3 ± 0.3‰); recycled: subdued εHf(t) and/or sub-/supra-mantle δ18O | Belt | LA-ICP-MS/MC-ICP-MS + SIMS | Propagate 2σ; avoid mixed-age spot averaging. | [18,19] |

| Greenstone affinities | HFSE/LILE (e.g., Nb anomaly; Th/Yb-Nb/Yb) | Arc-like: negative Nb anomaly, moderate Th/Yb-Nb/Yb; back-arc/plume: diminished Nb anomaly, elevated Ti | Belt | Immobile-element diagrams | Use chondrite/MORB normalization consistently. | [23,47] |

| Alteration footprint | Carbonate–sulfide–albite halo width | Ashanti-like: ≥500–1000 m cumulative; Sefwi-like: ≤200–400 m | District | Field mapping + multi-sensor imagery | Sum stacked envelopes; note structural repeats. | [3,13,41] |

| Hydrothermal textures | Crack-seal/fault-valve indicators | Presence correlates with mapped dilation loci | District | Microstructures, vein-swarm statistics | Qualitative → semi-quantitative scoring. | [39,40,43] |

| Proximity test | Camp centroid to corridor core | ≥70% of camps within ±15 km (target benchmark) | Belt | Spatial join (camp → THG core) | Report sensitivity to buffer size. | [4,11] |

| Model reproducibility | Data processing transparency | Grid spacing ≤ 10 km; filters documented; versions/DOIs logged | All Scales | Processing audit log (supplement) | Provide script and parameter file. | [5] |

| Level | Gate ID | Decision Gate | Go (Pass) Rule | Stop/Revise Rule | Required Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Craton | C1 | Tectonic context: Birimian orogenic gold province? | Region includes Birimian terranes with known transcurrent shear belts (orogenic gold model applicable). | Outside Birimian provinces or deposit model mismatch (e.g., IOCG/porphyry-dominated context). | 1:5 M context map + short rationale memo |

| Craton | C2 | Gold endowment precedent within 500 km | ≥1 Moz cumulative historic/modern endowment within ~500 km (or multiple operating/historic mines). | No significant endowment known → proceed only if other gates are strong; treat as lower priority. | Endowment overlay map (buffered radius) |

| Craton | C3 | Data sufficiency baseline | At least two core datasets available at regional coverage (geology + airborne magnetics). | Fewer than two core datasets → STOP and compile minimum inputs first. | Data inventory table (coverage, vintage, resolution) |

| Belt | B1 | Trans-lithospheric corridor (THG) presence | Continuous, linear/high-gradient corridor 10–50 km wide and ≥150 km long with coherent strike. | Corridor discontinuous, short, or dominated by artifacts → REVISE/hold. | Corridor map with buffers (RTP/gradients) |

| Belt | B2 | Crustal architecture inheritance (Moho/LAB steps) | Target corridor aligns with Moho/LAB step or deep-root anisotropy (supportive evidence). | No architectural support; treat as surface-only feature (downgrade). | Architecture overlay figure |

| Belt | B3 | Belt-scale data quality | Magnetic line spacing ≤200 m (or best available) and geology ≤1:200k with coherent leveling/metadata. | Patchy, undocumented, mixed vintages controlling targets → STOP and improve inputs. | QA/QC checklist + metadata memo |

| Segment | S1 | Releasing jogs/step-overs | Dilational jog consistent with shear sense; 2–20 km wavelength implying opening. | Purely compressional bends or ambiguous kinematics. | Jog inventory map + kinematics note |

| Segment | S2 | Relay ramps and linkage zones | Overlapping shear segments with relay ramp width ~1–5 km; damage zones expected. | Isolated single shear with no overlap or linkage. | Relay/overlap sketch and target polygons |

| Segment | S3 | Vertical pathway continuity | Aligned multi-scale features from site to belt corridor (stacked lineaments, continuous lows/highs). | Disconnected local lineaments without belt-scale plumbing. | Pathway continuity diagram |

| Site | T1 | Historical showings/occurrences | Documented Au-sulfide quartz-carbonate showings within ~10–20 km of segment hot spots. | No occurrences and poor exposure → lower priority or HOLD. | Occurrence pins + brief notes |

| Site | T2 | Intersection density (structure network) | Multiple structure intersections within ~1–2 km2 (splays, R-R’ shears, subsidiary faults). | Single, isolated fracture with no network connectivity. | Intersection count sheet and target box |

| Site | T3 | ESG and Permitting Gate | No red-flag ESG constraints for early reconnaissance work. | Critical ESG red flags (communities, protected areas, heritage) → STOP until resolved. | ESG gate form and constraint map |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dia, I.; Faye, C.I.; Sy, B.; Guéye, M.; Furman, T. A Protocol-Oriented Scoping Review for Map-First, Auditable Targeting of Orogenic Gold in the West African Craton (WAC): Deferred, Out-of-Sample Evaluation. Minerals 2025, 15, 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121282

Dia I, Faye CI, Sy B, Guéye M, Furman T. A Protocol-Oriented Scoping Review for Map-First, Auditable Targeting of Orogenic Gold in the West African Craton (WAC): Deferred, Out-of-Sample Evaluation. Minerals. 2025; 15(12):1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121282

Chicago/Turabian StyleDia, Ibrahima, Cheikh Ibrahima Faye, Bocar Sy, Mamadou Guéye, and Tanya Furman. 2025. "A Protocol-Oriented Scoping Review for Map-First, Auditable Targeting of Orogenic Gold in the West African Craton (WAC): Deferred, Out-of-Sample Evaluation" Minerals 15, no. 12: 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121282

APA StyleDia, I., Faye, C. I., Sy, B., Guéye, M., & Furman, T. (2025). A Protocol-Oriented Scoping Review for Map-First, Auditable Targeting of Orogenic Gold in the West African Craton (WAC): Deferred, Out-of-Sample Evaluation. Minerals, 15(12), 1282. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15121282