Expropriation of Real Property in Kigali City: Scoping the Patterns of Spatial Justice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To which degrees are the law, processes and outcomes of expropriation in Kigali city in line with patterns of spatial justice?

- Is compensation always determined at market value?

- How satisfied are expropriated people with the received compensation?

- Does the paid compensation allow expropriated people to acquire other assets and to pursue their livelihoods in the same city?

2. Conceptual Framework

- Very unjust trends: less than 1 score or less than 20%

- Unjust trends: between 1 and less than 2 scores or between 20% and less than 40%

- Relatively unjust/just trends: between 2 and less than 3 scores or between 40 % and less than 60%

- Just trends: between 3 and less than 4 scores or between 60% and less than 80%

- Very just trends: between 4 and 5 or between 80% and 100%

3. Data Sources and Methods

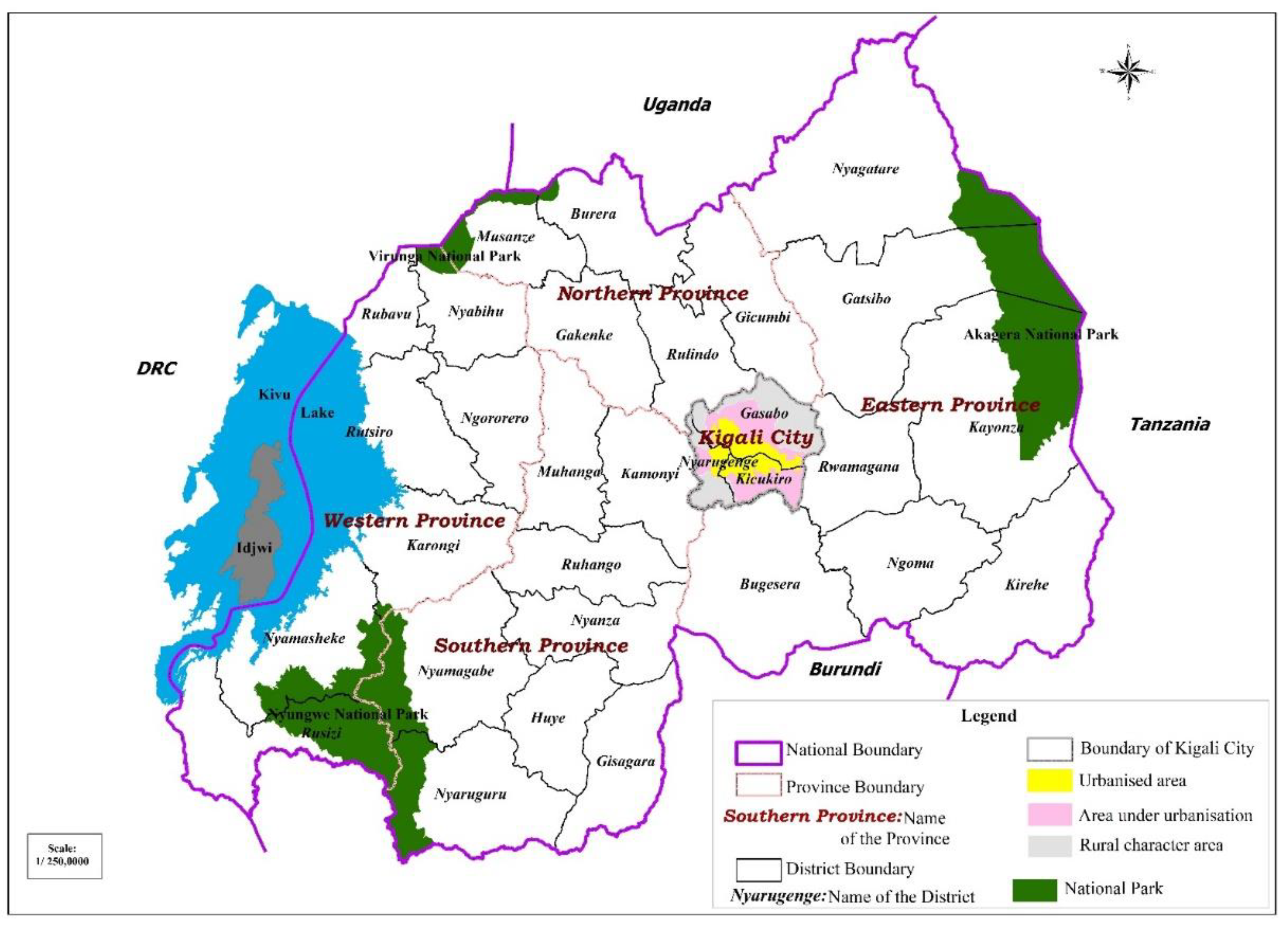

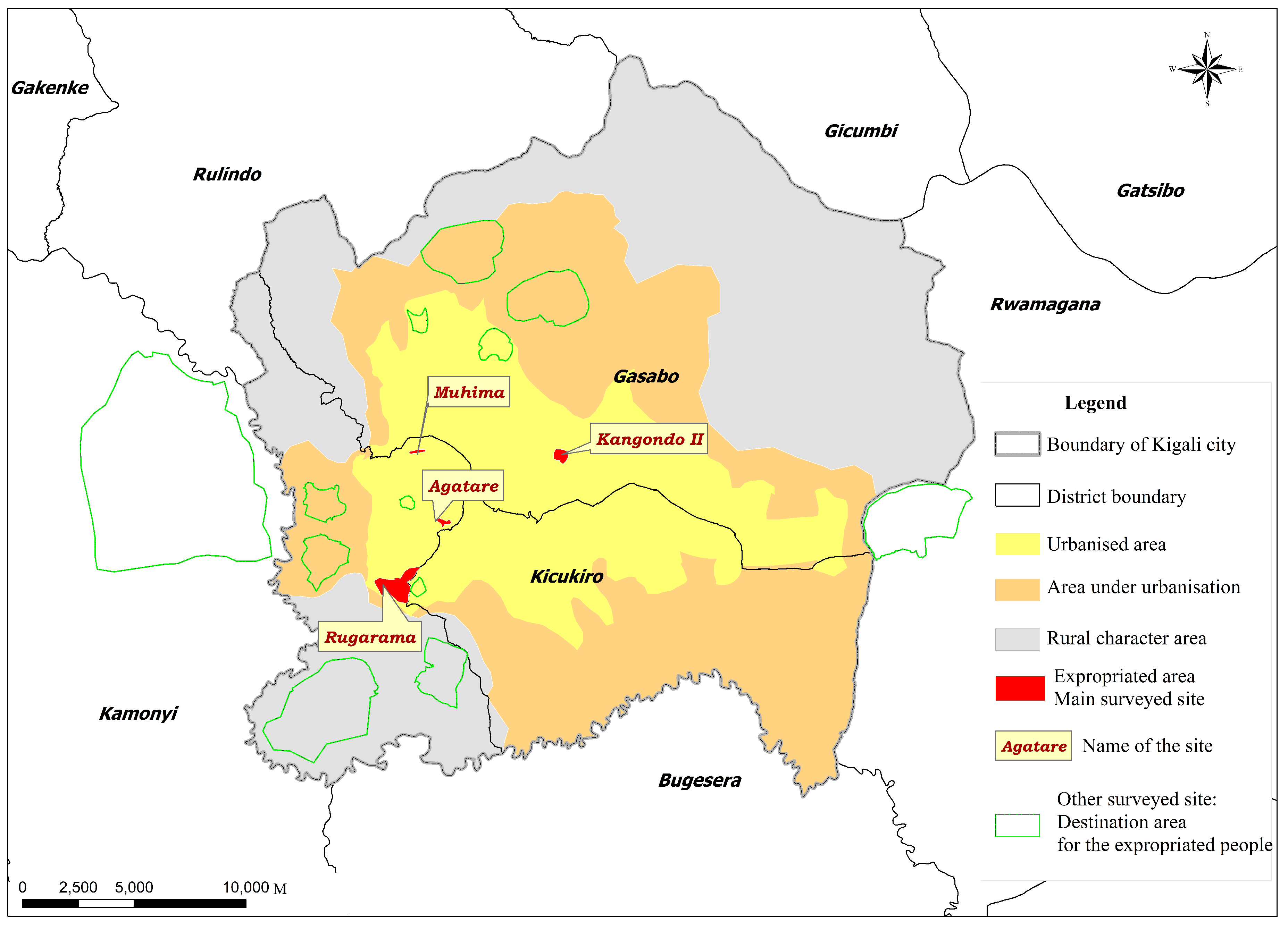

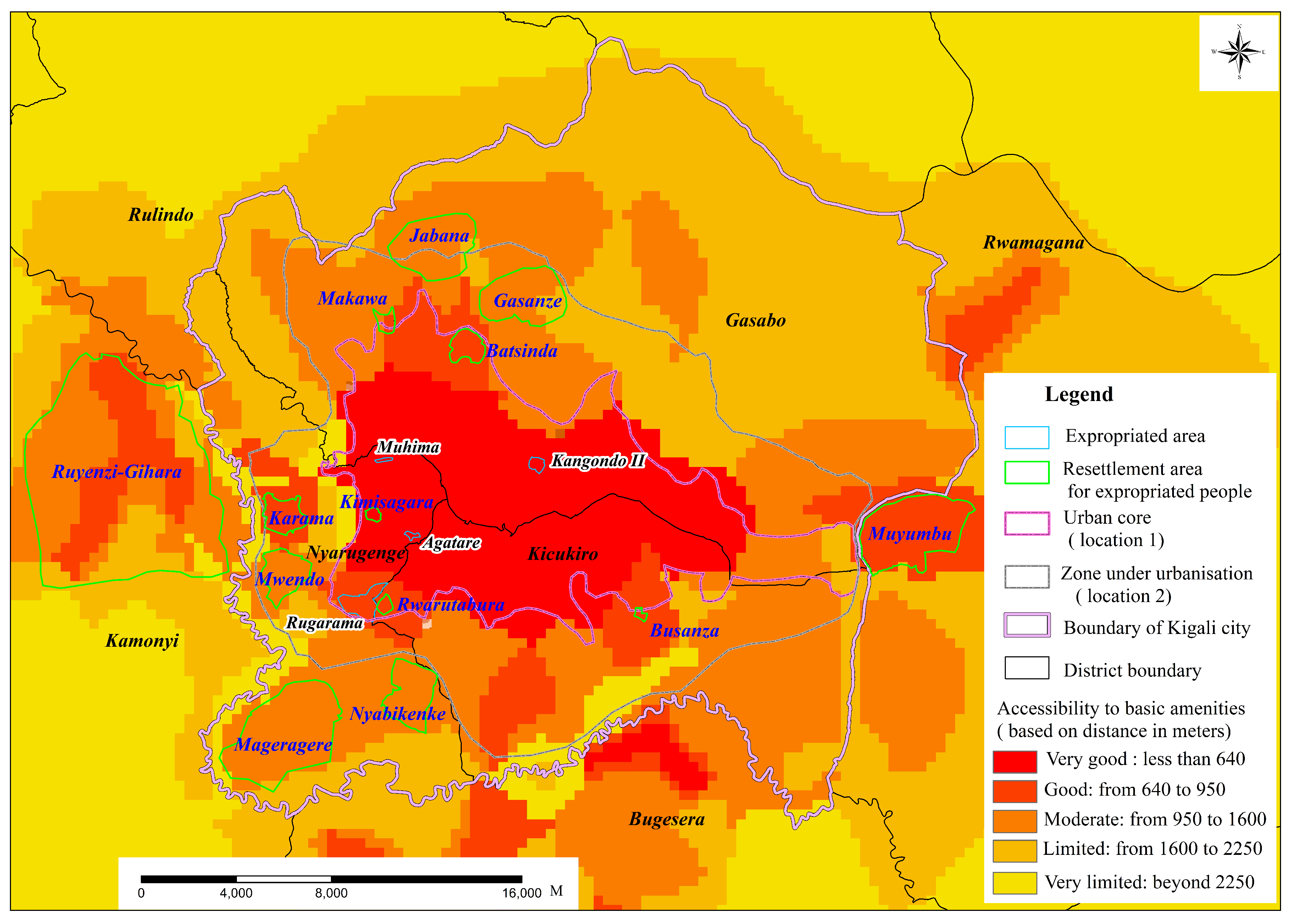

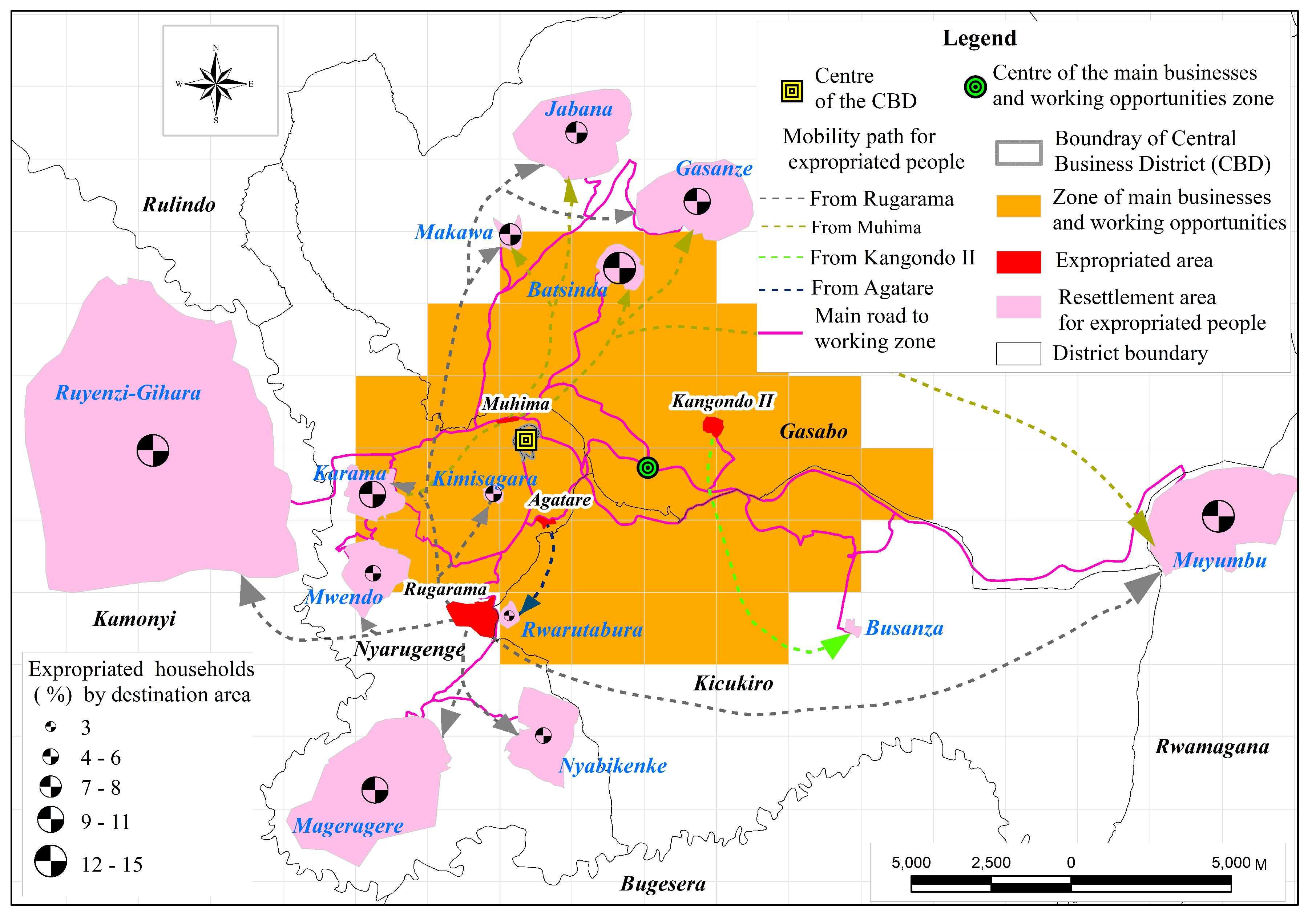

3.1. Study Areas and Sampling

3.2. Data Collection

3.2.1. Primary Data

3.2.2. Secondary Data

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Patterns of Spatial Justice in the Law and Processes of Expropriation and Compensation

4.1.1. Procedural Justice and Compliance Dilemma

4.1.1.1. The Fallacy of Public Interest

“The law does not grant Kigali city and its constituent districts the power to initiate the expropriation for a real estate agency whose projects consist of developing apartments for rent or sale3.”

“District authorities use the expropriation for public interest as a strategy to attract private investors. They initiate the expropriation which may result in paying low compensation, while its purpose is for private investment. However, if the investors negotiate with property owners, the compensation value may be higher. Paying low compensation can be a ground for collaboration between districts and investors who contribute in implementing socio-economic development programmes some of which are counted while evaluating the performances of the districts4.”

“Letting property owners negotiate the compensation with the investors can result in long processes, high speculation on property prices and demand for excessive compensation. This can result in either delay in the start of the project of the investors or its abandon. Those investors create jobs for the public. Some of them contribute in mitigating the shortage of modern residential buildings5.”

“If Kigali city and its constituent districts carry out the expropriation for private investors and property owners are not satisfied with the compensation, they can appeal and proceed with the counter-valuation. The law is clear6.”

4.1.1.2. Lack of Neutrality in Calculating Compensation

4.1.2. Trends of Procedural, Recognitional and Redistributive Justice

4.1.2.1. Negotiation on the Compensation Option/Value and Participation in Valuation

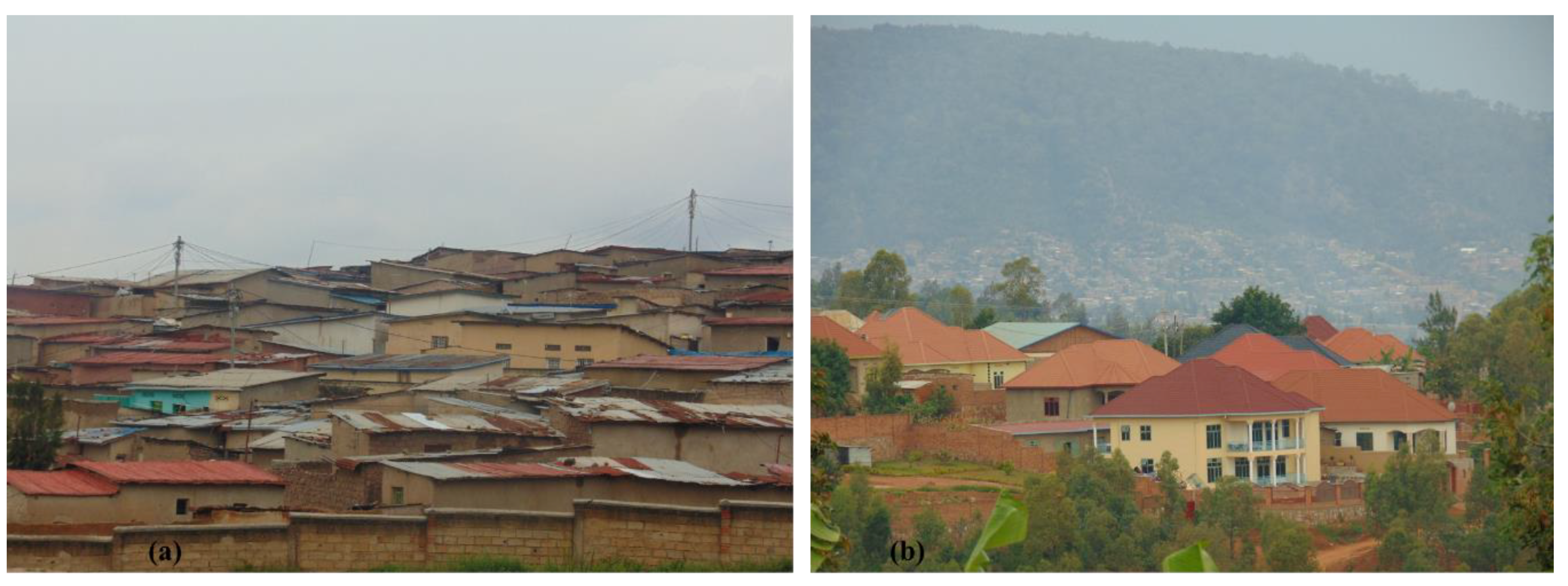

“Keeping paying money as compensation option to the expropriated people thrives informal settlements in Kigali city and its outskirts. Property owners whose houses are of poor quality receive little money as compensation. They move to urban fringes where they build up new poor quality housing and henceforth contribute to the spread of slums, which are being cleared alongside the implementation of the current master plan. The practice for compensation in cash should stop8,9.”

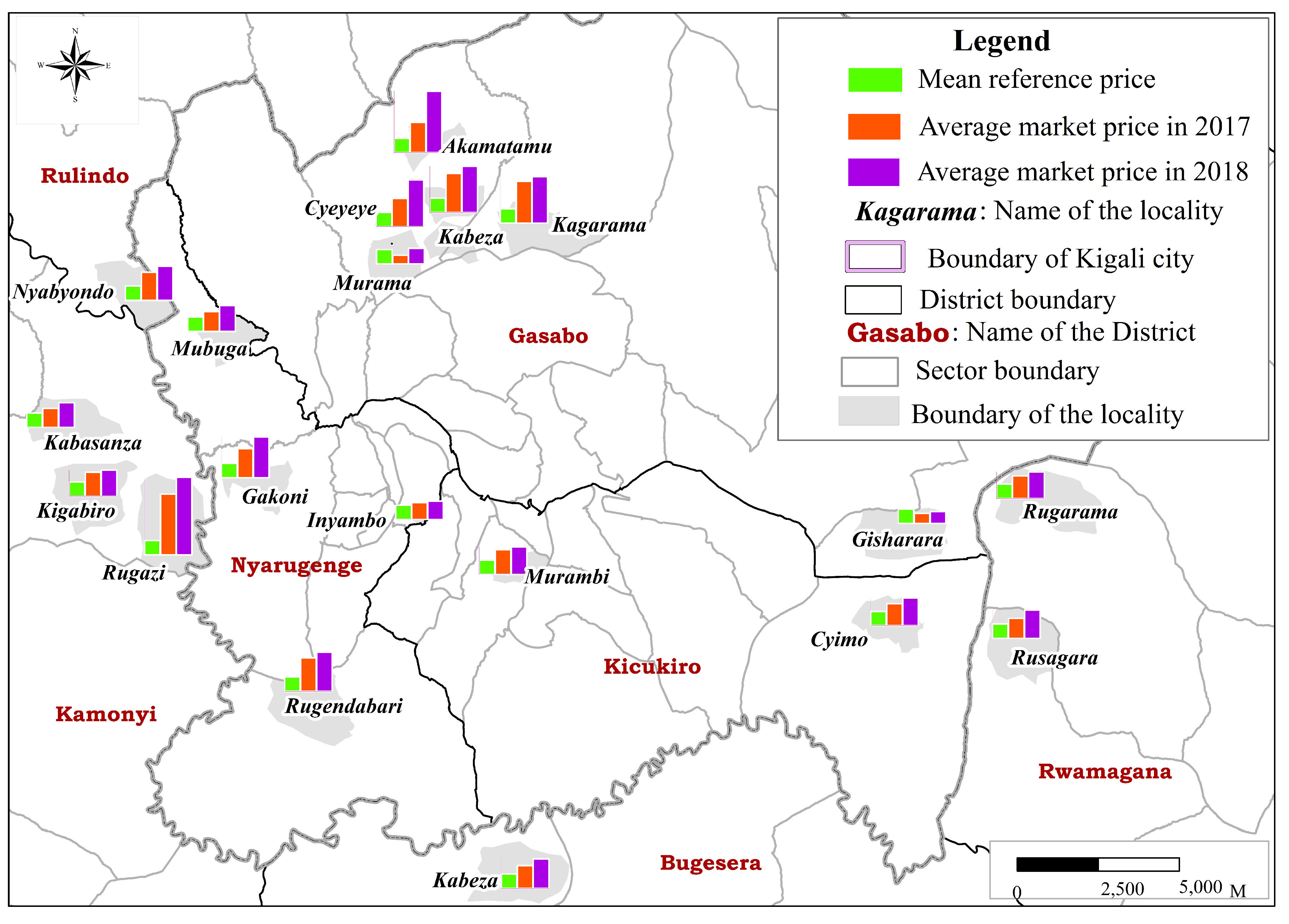

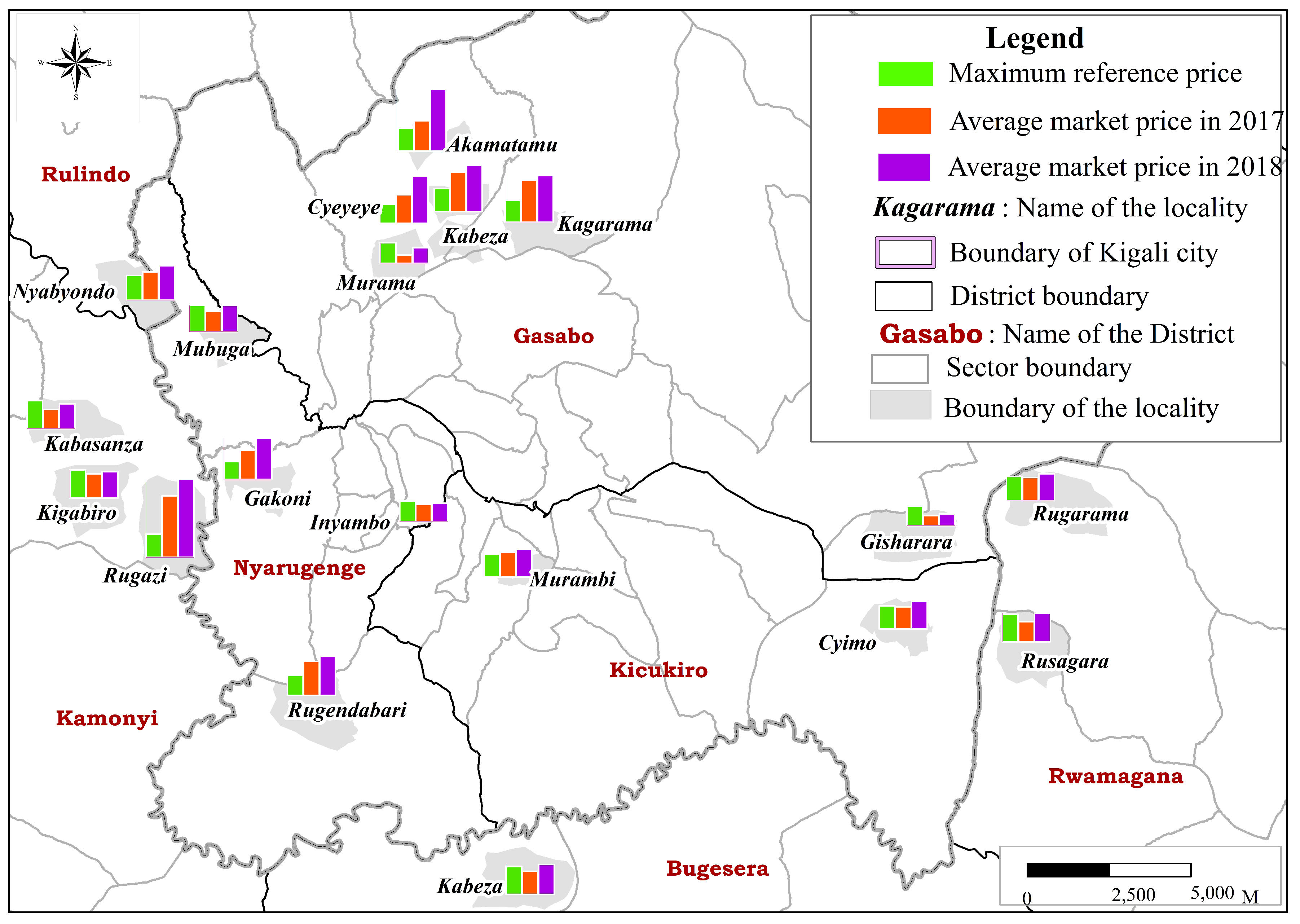

4.1.2.2. Compensation at the Market Prices

“District authorities feel a need to implement some urban development projects for their best appraisal, even though the cost for the expropriation has not been secured enough12.”

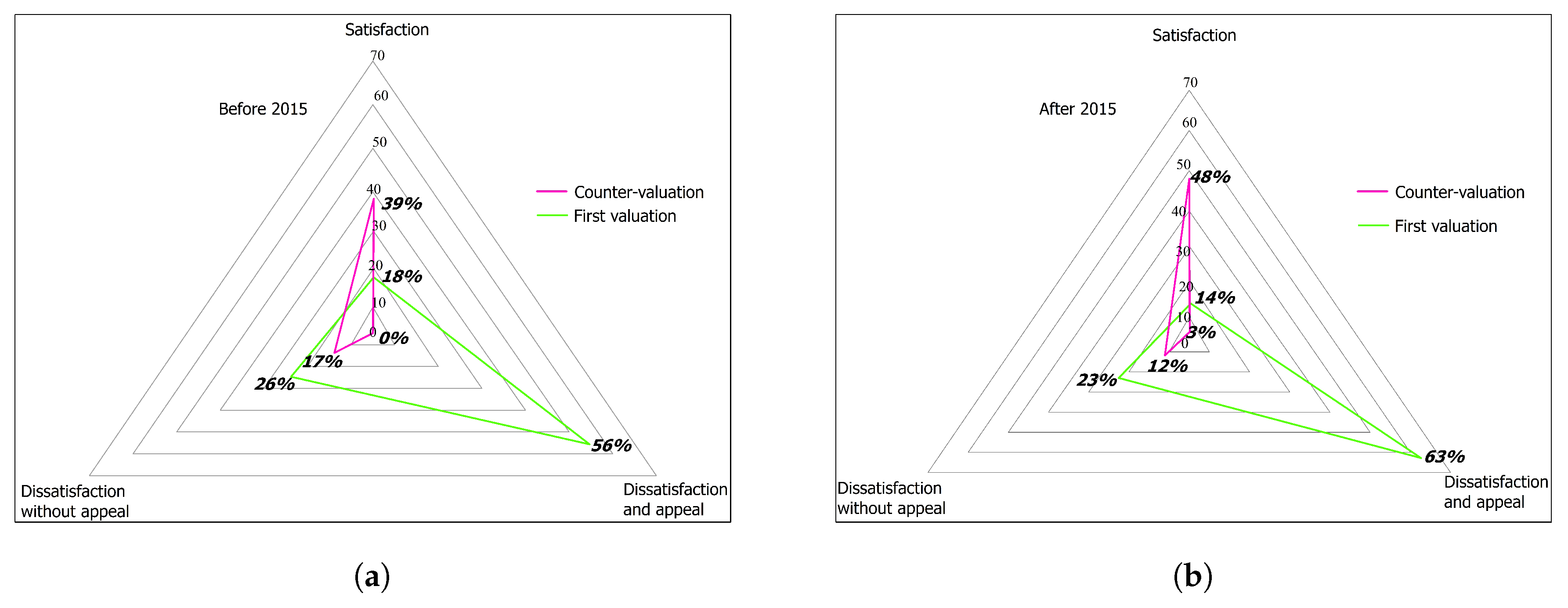

4.1.2.3. Satisfaction on the Compensation Value

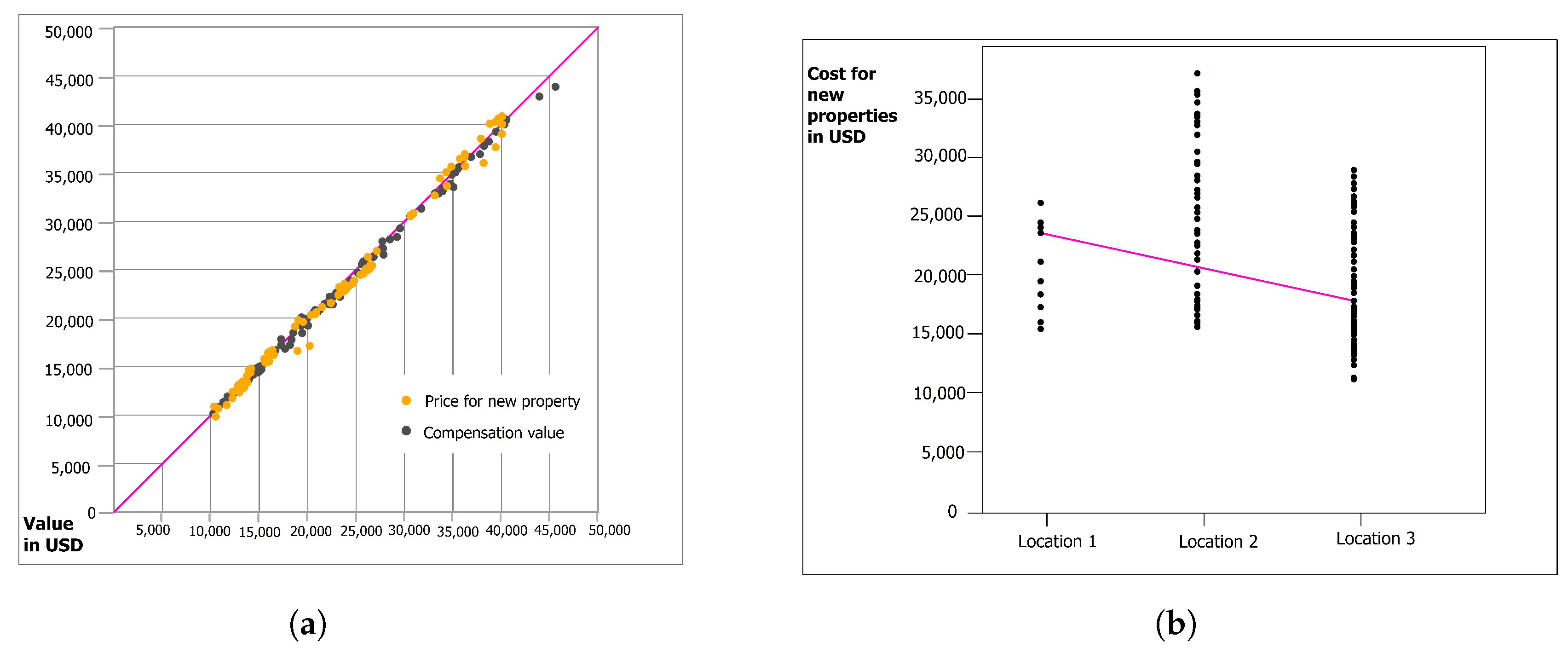

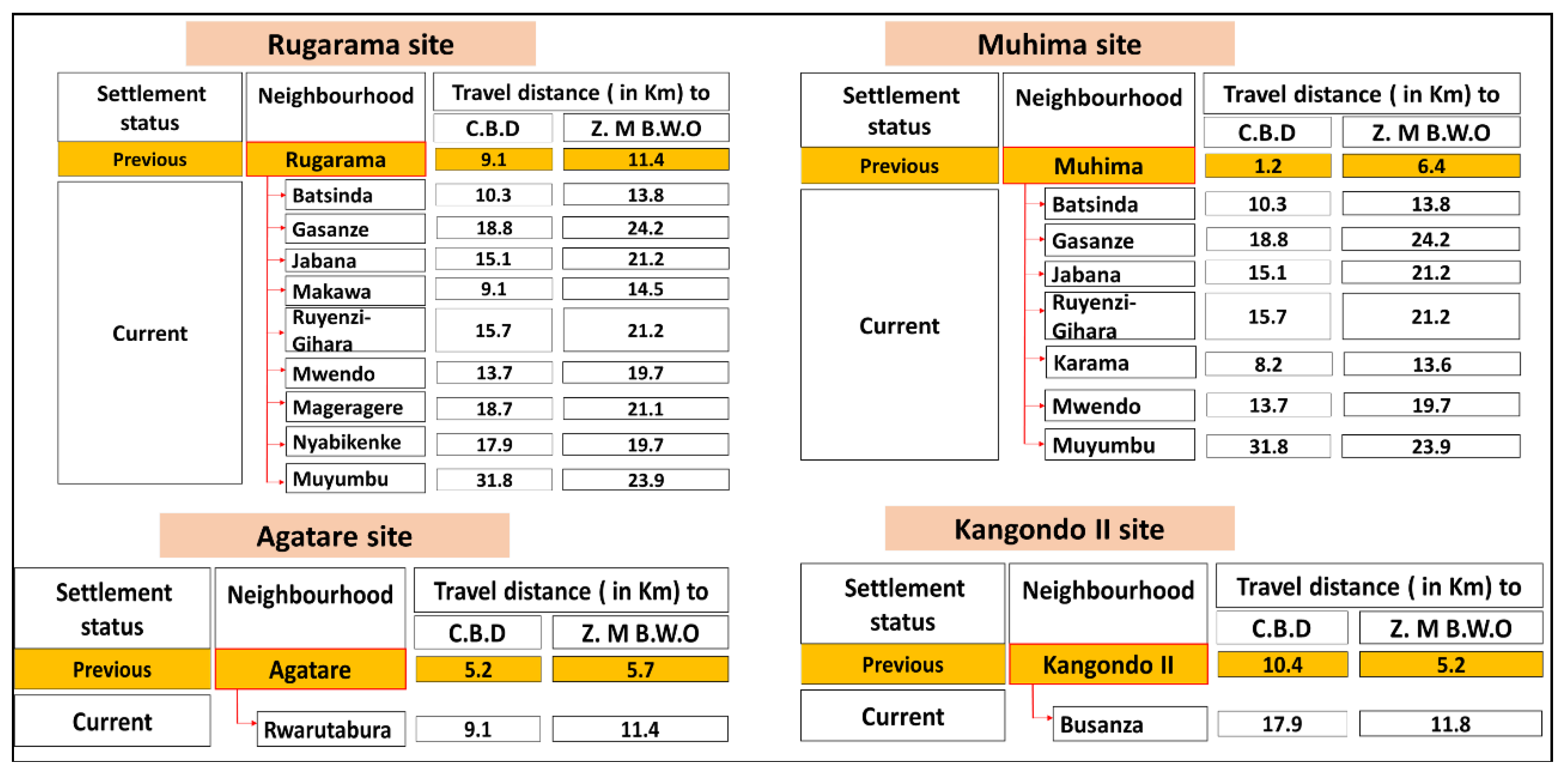

4.2. Paucity of Redistributive Justice

4.2.1. Access to New Properties in the Close Vicinity

4.2.2. Decreased Access to Basic Infrastructure and Services

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

- ▪

- It promotes the compensation (recognitional and redistributive justice) regardless of tenure status.

- ▪

- It advances sharing the power of eminent domain because private investors can carry out the expropriation if the implementation process of the law opens room for those investors to directly negotiate with property owners on compensation (procedural, recognitional and redistributive justice).

- ▪

- It grants property owners the rights to use the counter-valuation process, in order to claim for just compensation (procedural, recognitional and redistributive justice).

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Indicator | Measurement Approach | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Presence of legal provisions defining the public interest as rationale for government agencies to undertake expropriation | Likert scale |

| 2 | Government agencies execute expropriation for the sole public interest | Likert scale |

| 3 | Percentage of expropriated people whose properties were expropriated by government agencies for public interest | Percentages |

| 4 | Presence of legal provisions for calculating the compensation value by an independent valuer | Likert scale |

| 5 | Compensation value is calculated by independent valuer | Likert scale |

| 6 | Percentage of expropriated people whose compensation value was calculated by independent valuer | Percentages |

| 7 | Presence of legal provisions for negotiating the compensation option between the expropriating agency and the property owners | Likert scale |

| 8 | Consensus on compensation option is reached between expropriating agency and property owners prior to valuation | Likert scale |

| 9 | Percentage of expropriated people who negotiated compensation with expropriating agency | Percentages |

| 10 | Presence of legal provisions for negotiating compensation value between the expropriating agency and the property owners | Likert scale |

| 11 | Property owners actively participate in valuation process and negotiate on compensation value | Likert scale |

| 12 | Percentage of expropriated people who actively participated in valuation process and negotiated compensation value | Percentages |

| 13 | Presence of the legal provisions on compensation at market prices | Likert scale |

| 14 | Compensation is calculated at market prices | Likert scale |

| 15 | Percentage of expropriated people whose compensation has been calculated at market prices | Percentages |

| 16 | Presence of legal provisions on processes of appealing against dissatisfactory expropriation process | Likert scale |

| 17 | Presence of accessible appealing system for handling claims on dissatisfactory compensation value or option | Likert scale |

| 18 | Percentage of the expropriated people who are satisfied with compensation at first valuation process- | Percentages |

| 19 | Percentage of expropriated people who accessed appealing system and claimed against dissatisfactory compensation value or option | Percentages |

| 20 | Percentage of expropriated people who are satisfied with the compensation after appealing/ counter valuation | Percentages |

| 21 | Use of the compensation to access other properties in the close neighbourhoods | Percentages |

| 22 | Percentage of expropriated people who afford other properties at the open market, using the compensation fees | Percentages |

Appendix B

Appendix C

| District | Site or Locality | Purpose for Expropriation | Year of Expropriation | Number of the Property Owners | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyarugenge | Rugaramana | Development of affordable housing. The whole area was cleared after the expropriation. | 2014 | 275 | 72 |

| Agatare | Slum upgrading: Few private land plots and buildings were expropriated for the development of roads, sewerage system and green spaces. | 2017 | 43 | 30 | |

| Muhima | Extension of the existing road. Small tracks of land plots and some buildings were expropriated. | 2017 | 49 | 33 | |

| Gasabo | Kangondo II | Development of affordable housing. The whole area will be cleared. The valuation processes is already conducted. Property owners are still living in the area because there is pending claim on the compensation option. | 2017–2018 | 168 | 62 |

| 535 | 197 |

Appendix D

| Characteristic | Class/Category | Number of Respondents | Percentage (%) | Total Number of Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 144 | 73 | 197 |

| Female | 53 | 27 | ||

| Age range | 20–25 | 5 | 2.5 | 197 |

| 25–35 | 39 | 19.8 | ||

| 35–45 | 48 | 24.4 | ||

| 45–55 | 66 | 33.5 | ||

| 55–65 | 31 | 15.7 | ||

| Over 65 | 8 | 4.1 | ||

| Marital status | Single | 6 | 3.0 | 197 |

| Married | 167 | 84.8 | ||

| Widow | 24 | 12.2 | ||

| Education level | None | 6 | 3.0 | 197 |

| Primary | 71 | 36.0 | ||

| Secondary | 79 | 40.1 | ||

| Tertiary | 41 | 20.8 | ||

| Income level (per month, in USD) | 70–150 | 31 | 15.7 | 197 |

| 150–220 | 2 | 1.0 | ||

| 220–300 | 59 | 29.9 | ||

| 300–365 | 52 | 26.4 | ||

| 365–440 | 5 | 2.5 | ||

| 440–510 | 15 | 7.6 | ||

| 510–585 | 19 | 9.6 | ||

| 585–660 | 6 | 3.0 | ||

| 660–730 | 3 | 1.5 | ||

| 730–805 | 4 | 2.0 | ||

| 880–950 | 1 | 0.5 |

Appendix E

| Locality | Village | Period of Land Transaction and Land Price Per Square Meter in Rwandan Francs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | Increase in % | ||

| Muyumbu | Rugarama | 2917 | 3333 | 4167 | 5000 | 71 |

| Nyakaliro | Rusagara | 1667 | 2000 | 2500 | 3667 | 120 |

| Masaka | Cyimo | 13,333 | 16,667 | 18,333 | 20,833 | 56 |

| Rwezamenyo | Rugendabari | 2500 | 3333 | 4167 | 5000 | 100 |

| Karama | Gakoni | 10,625 | 12,500 | 16,250 | 20,000 | 88 |

| Jabana_1 | Cyeyeye | 12,500 | 13,333 | 15,000 | 16,667 | 33 |

| Bisambu | Murambi | 6250 | 7500 | 8750 | 10,000 | 60 |

| Karumuna | Kabeza | 2933 | 3333 | 4000 | 5333 | 82 |

| Ruyenzi | Kigabiro | 4583 | 5833 | 6667 | 7500 | 64 |

| Kanyinya | Mubuga | 2500 | 3000 | 3750 | 5000 | 100 |

| Rutonde | Nyabyondo | 2500 | 3000 | 3333 | 4167 | 67 |

| Rusororo-Nyagahinga | Gisharara | 3200 | 4000 | 6000 | 8000 | 150 |

| Ruyenzi | Rugazi | 5333 | 6667 | 8000 | 9333 | 75 |

| Ruyenzi | Kabasanza | 2000 | 2667 | 4000 | 5333 | 167 |

| Gasanze | Kagarama | 6667 | 8000 | 10,667 | 13,333 | 100 |

| Kabuye | Kabeza | 6800 | 9068 | 11,412 | 19,500 | 187 |

| Kabuye | Murama | 3685 | 4850 | 6000 | 11,350 | 208 |

| Akamatamu | Akamatamu | 3154 | 4140 | 5085 | 10,725 | 240 |

| Nyarugenge_Agatare | Inyambo | 13,800 | 14,500 | 16,150 | 18,000 | 30 |

Appendix F

| Age | Sex | Level of Education | Marital Status | Year of Expropriation | Opinions on or Drivers for Appealing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55 | F | Primary | Married | 2017 | “I have fear for appealing, though I am not satisfied with the compensation. Local community does not have to challenge the government.” |

| 57 | M | Secondary | Married | 2017 | “That (compulsory real property acquisition) started some years ago, when they introduced the lease property regime. As the land belongs to the government, it is not worth claiming. They can even take the land without compensation.” |

| 49 | F | Primary | Widow | 2014 | “I was not satisfied with the compensation. I did not appeal because other people who appealed did not receive positive feedback from the expropriating agency.” |

| 47 | M | University | Married | 2014 | “I follow the land market information. I appealed. It is my right. Through counter-valuation I received a higher compensation value than the one that was determined during the first valuation.” |

| 53 | M | None | Married | 2014 | “None can resist against the government decision. All people that I know and who claimed did not get a positive feedback.” |

| 67 | M | None | Married | 2017 | “We accept to receive low compensation without complaining because we do not want to challenge the government process. I cannot spend a little money that I have on appealing. How can I be sure that the counter valuation will be in my favour?” |

| 39 | M | University | Married | 2017 | “The calculated value for the compensation was too low. If I had to sell my house at the open market, I could receive much money. I appealed. After the counter-valuation, the compensation value was increased at 45%.” |

| 62 | F | Primary | Widow | 2017 | “The compensation value was too low, compared to the price at which I can sell my house at the open market. But, I did not appeal. I could not find 60, 000 Rfws for the payment of the counter-valuation process.” |

References

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning and National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. Fourth Population and Housing Census, Rwanda, 2012; Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning and National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda: Kigali, Rwanda, 2014. Available online: www.statistics.gov.rw/survey-period/fourth-population-and-housing-census-2012 (accessed on 07 June 2018).

- Manirakiza, V. Urbanization Issue in the Era of Globalization: Perspectives for Urban Planning in Kigali. In Social Studies for Community Cohesion and Sustainable Development; International Household Survey Network: Kigali, Rwanda, 2012; Available online: https://docplayer.net/21199533-Urbanization-issue-in-the-era-of-globalization-perspectives-for-urban-planning-in-kigali-vincent-manirakiza.html (accessed on 07 June 2017).

- World Bank Group. Reshaping Urbanization in Rwanda: Urbanization and the Evolution of Rwanda’s Urban Landscape; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; 40p, Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29081 (accessed on 07 June 2018).

- Rwanda Environment Management Authority. Kigali: State of Environment and Outlook Report 2013; Rwanda Environment Management Authority: Kigali, Rwanda, 2013; 40p. Available online: http://www.minirena.gov.rw/fileadmin/Media_Center/Documents/kigali_soe_part1-1.pdf (accessed on 07 June 2018).

- Ministry of Infrastructure. National Urbanization Policy; Ministry of Infrastructure: Kigali, Rwanda, 2015; 52p. Available online: www.mininfra.gov.rw/fileadmin/Rwanda_National_Urbanization_Policy_2015.pdf (accessed on 07 June 2018).

- Ministry of Infrastructure. National Housing Policy; Government of Rwanda: Kigali, Rwanda, 2015; 63p. Available online: www.rha.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/Documents/.../National_Housing_Policy.pdf (accessed on 07 June 2018).

- City of Kigali. The City of Kigali Development Plan (2013–2018); City of Kigali: Kigali, Rwanda, 2013; 98p. Available online: http://www.kigalicity.gov.rw/fileadmin/Template/Documents/policies/Kigali_City_Development_Plan__2013-2018__City_development_Plan_pdf (accessed on 08 June 2018).

- Goodfellow, T.; Smith, A. From Urban Catastrophe to ‘Model’ City? Politics, Security and Development in Post-conflict Kigali. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 3185–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manirakiza, V.; Ansoms, A. Modernizing Kigali: The struggle for space in the Rwandan urban context. In Losing Your Land Dispossession in the Great Lakes; Ansoms, A., Hilhorst, T., Eds.; Boydell and Brewer: Woodbridge, NJ, USA, 2014; 218p. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, T. Rwanda’s political settlement and the urban transition: Expropriation, construction and taxation in Kigali. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2014, 8, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Rwanda. Law N° 32/2015 of 11/06/2015 Relating to Expropriation in the Public Interest; Government of Rwanda: Kigali, Rwanda, 2015; 54p. Available online: https://landportal.org/library/resources/rwanda-land-lawspolicies-2/law-n%C2%B0-322015-11062015-relating-expropriation-public (accessed on 08 June 2018).

- Tagliarino, N.K.; Bununu, Y.A.; Micheal, M.O.; de Maria, M.; Olusanmi, A. Compensation for Expropriated Community Farmland in Nigeria: An In-Depth Analysis of the Laws and Practices Related to Land Expropriation for the Lekki Free Trade Zone in Lagos. Land 2018, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoops, B.; Marais, E.J.; Mostert, H.; Sluysman en, J.A.M.A.; Verstappen, L.C.A. Rethinking Expropriation Law I: Public Interest in Expropriation; Eleven International Publishing: Hague, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 6, 410p. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, H.; Mugisha, F.; Kananga, A.; Clay, D. The implementation of Rwanda’s expropriation law and its Outcomes on the population. In Proceedings of the 2016 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 March 2016; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.land-links.org/research-publication/the-implementation-of-rwandas-expropriation-law-and-its-outcomes-on-the-population/ (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- Legal Aid Forum. The Implementation of Rwanda’s Expropriation Law and Outcomes on the Population: Final Report; USAID: Kigali, Rwanda, 2015; 231p, Available online: https://landportal.org/fr/library/resources/rwanda-land-research-104/final-report-rwanda%E2%80%99s-expropriation-law-and-outcomes (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- He, J.; Sikor, T. Notions of justice in payments for ecosystem services: Insights from China’s Sloping Land Conversion Program in Yunnan Province. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwayezu, E.; de Vries, T.W. Indicators for Measuring Spatial Justice and Land Tenure Security for Poor and Low Income Urban Dwellers. Land 2018, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Tenure of Land, Fisheries and Forests in the context of National Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; Available online: http://www.fao.org/tenure/voluntary-guidelines/en/ (accessed on 27 September 2018).

- Hoops, B.; Marais, E.J.; van Schalkwyk, L.; Tagliarino, N.K. (Eds.) Rethinking Expropriation Law III. Fair Compensation; Eleven International Publishing: Hague, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 9, 244p. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Environmental and Social Standard 5 Land Acquisition, Restrictions on Land Use and Involuntary Resettlement; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; 13p, Available online: https://consultations.worldbank.org/Data/hub/files/consultation-template/review-and-update-world-bank-safeguard-policies/en/materials/proposed_environmental_and_social_standards_-_ess5_factsheet_and_standard.pdf (accessed on 03 October 2018).

- Nozick, R. Anarchy, State, and Utopia; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1974; 367p, ISBN 9780465097203. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Revised Edition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; 560p, ISBN 9780674000780. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S.S. Spatial justice and planning. Justice Spatiale|Spatial Justice 2009. Available online: http://www.jssj.org (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Gutwald, R.; Leßmann, O.; Masson, T.; Rauschmayer, F. A Capability Approach to Intergenerational Justice? Examining the Potential of Amartya Sen’s Ethics with Regard to Intergenerational Issues. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 2014, 15, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E. The City and Spatial Justice. Justice Spatiale|Spatial Justice 2009. pp. 31–39. Available online: https://www.jssj.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/JSSJ1-5en1.pdf. (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Ferrari, E. Competing Ideas of Social Justice and Space: Locating Critiques of Housing Renewal in Theory and in Practice. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2012, 12, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Watkins, C. Representations of Space, Spatial Practices and Spaces of Representation: An Application of Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad. Cult. Organ. 2005, 11, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Recognition without Ethics? Theory Cult. Soc. 2001, 18, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990; 286p, ISBN 9780691023151. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N.; Honneth, A. Redistribution or Recognition? A Political-philosophical Exchange; Verso Books: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2003; 276p, ISBN 1859844928. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, R.L.; Daniels, S.E.; Stankey, G.H. Procedural justice and public involvement in natural resource decision making. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1997, 10, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, S. Remodeling Just Compensation: Applying Restorative Justice to Takings Law Doctrine. Can. J. Law Jurisprud. 2017, 30, 413–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.; Leben, S. Procedural Fairness: A Key Ingredient in Public Satisfaction. Court Rev. J. Am. Judges Assoc. 2007, 44, 226. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991; 464p. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Augustinus, C.; Enemark, S.; Munro-Faure, P. Innovations in Land Rights Recognition, Administration, and Governance; World Bank Studies; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Knetsch, J.L.; Borcherding, T.E. Expropriation of Private Property and the Basis for Compensation. Univ. Tor. Law J. 1979, 29, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a ‘Post-Socialist’ Age. New Left Rev. I 1995, 212, 68–93. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, W.T.; Uchendu, E.C. Responsible land management-Concept and application in a territorial rural context fub. Flächenmanagement und Bodenordnung 2017, 2, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Selod, H.; Burns, A. The Land Governance Assessment Framework: Identifying and Monitoring Good Practice in the Land Sector; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; 380p. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) and Centre for Geographic information Systems and Remote Sensing of the University of Rwanda(CGIS-UR). Administrative Map of Rwanda; CGIS-UR: Kigali, Rwanda, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaswamy, K.N.; Sivakumar, A.I.; Mathirajan, M. Management Research Methodology: Integration of Principles, Methods and Techniques; Pearson Education: Bengaluru, India, 2006; 600p, ISBN 8131767779. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, H. Triangulation, Respondent Validation, and Democratic Participation in Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Real Property Valuers in Rwanda. Rwanda Lands and Property Incorporated Thereon Reference Prices; Institute of Real Property: Kigali, Rwanda, 2018; 346p, Available online: https://rwandalii.africanlii.org/content/official-gazette-n%C2%BA-special-8112018 (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Börzel, T.A.; Hofmann, T.; Panke, D. Caving in or sitting it out? Longitudinal patterns of non-compliance in the European Union. J. Eur. Public Policy 2012, 19, 454–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwanda Governance Board. Citizen Report Card-CRC 2017; Rwanda Governance Board: Kigali, Rwanda, 2017; 156p, Available online: http://rgb.rw/publications/citizen-report-card/ (accessed on 11 October 2018).

- Never Again Rwanda. Local Government Imihigo Process: Understanding the Factors Contributing to Low Citizen Participation; Never Again Rwanda: Kigali, Rwanda, 2018; 70p, Available online: http://neveragainrwanda.org/file/1389/download?token=mJ-gjTkT (accessed on 11 October 2018).

- Government of Rwanda. Law N° 17/2010 of 12/05/2010 Establishing and Organizing the Real Property Valuation Profession in Rwanda; Government of Rwanda: Kigali, Rwanda, 2010; 120p.

- Government of Rwanda. Ministerial Order N° 001/16.00 of 23/11/2009 Determining the Reference Land Prices in the City of Kigali; Government of Rwanda: Kigali, Rwanda, 2009; 12p. Available online: http://www.minicom.gov.rw/fileadmin/minicom_publications/law_and_regurations/Law_relating_to_electronic_messages_electronic_signatures_and_electronic_transactions.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2018).

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, X. Are they satisfied with land taking? Aspects on procedural fairness, monetary compensation and behavioral simulation in China’s land expropriation story. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwegian People’s Aid and Rwanda Civil Society Platform. Analysis of Land Expropriation and Transfer Process in Rwanda; Norwegian People’s Aid and Rwanda Civil Society Platform: Kigali, Rwanda, 2017; 85p, Available online: http://www.rcsprwanda.org/IMG/pdf/report_on_land.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; Geographies of Justice and Social Transformation Series; University of Georgia Press: Athens, GA, USA, 2010; Volume 1, 356p, ISBN 9780820336046. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | This will be referring to Kigali city and its constituent districts in this study. |

| 2 | Some aspects under evaluation relate to one or more forms of spatial justice. Those forms of spatial justice are therefore presented individually or in combination. |

| 3 | Interviews and household surveys. |

| 4 | Interviews with property valuers. |

| 5 | Interviews with local government leaders, members of district council, decision makers at MININFRA and high level authority and the Ministry of Justice. The budget for the expropriation is always estimated, without prior survey for the affected proprieties. |

| 6 | Ibid. |

| 7 | Interviews with urban planners and land managers. |

| 8 | Interview with land manager and urban planner in Gasabo district. |

| 9 | - Audio records from TV1, on expropriation in Kangondo II; March 2018. |

| 10 | Household survey. |

| 11 | Ibid. as 7. |

| 12 | Interviews with members of district council and property valuers. |

| 13 | Exchange rate of 684 Rwandan francs for 1USD, in April 2014. Data source: valuation rolls for the expropriated people in Rugarama site. |

| 14 | Exchange rate of 883.23 Rwandan francs for 1 USD. |

| Forms of Spatial Justice Under Evaluation2 | Evaluative Aspect | Measurement Indicators and Related Dimension of Spatial Justice | Related Research Question | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rules | Processes | Outcomes | Q 1 | Q 2 | Q 3 | Q 4 | ||

| Procedural | Expropriation is carried out for public interest | - Presence of legal provisions defining the public interest as rationale for government agencies to undertake expropriation. | - Government agencies execute expropriation solely for public interest. | - Percentage of expropriated people whose properties were expropriated by government agencies for public interest. | √ | |||

| Neutrality in the valuation | - Presence of legal provisions for calculating compensation value by independent valuer. | - Compensation value is calculated by independent valuer. | - Percentage of expropriated people consenting to the independency of valuer who calculated their compensations. | √ | ||||

| Procedural, recognitional and redistributive | Negotiation on compensation and participation in valuation | - Presence of legal provisions for negotiating compensation option between expropriating agency and property owners. | - Consensus on the compensation option is reached between expropriating agency and property owners prior to valuation. | - Percentage of expropriated people who negotiated compensation with expropriating agency. | √ | |||

| - Presence of legal provisions for negotiating the compensation value between expropriating agency and property owners. | - Property owners actively participate in valuation process and negotiate on compensation value. | - Percentage of expropriated people who actively participated in the valuation process and negotiated compensation value. | √ | |||||

| Compensation at market prices | - Presence of legal provisions on compensation at market prices. | - Compensation is calculated at market prices. | - Percentage of expropriated people whose compensation has been calculated at market prices. | √ | √ | |||

| Procedural and redistributive | Satisfaction with compensation | - Presence of legal provisions on the processes of appealing against non-satisfactory expropriation process. | - Presence of accessible appealing system for handling claims on the non-satisfactory compensation value or option. | - Percentage of the expropriated people who are satisfied with compensation at first valuation process. - Percentage of expropriated people who accessed appealing system and claimed against dissatisfactory compensation. - Percentage of expropriated people who are satisfied with compensation after appealing. | √ | √ | ||

| Redistributive | Access to new properties using compensation | - Use of compensation to access other properties in the close neighbourhoods. | - Percentage of expropriated people who afford other properties, using received compensation. | √ | ||||

| Forms of Spatial Justice | Evaluated Aspect | Period of Expropriation | Mean Score b | Sig*. (2-tailed) | Score on Outcomes and Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Law | Processes | Score in % a | Comments | ||||

| Procedural justice | Expropriation for public interest | Before 2015 | 2.95 | 1.16 | .001 | 0% | People whose properties were expropriated for public interest |

| After 2015 | 3.19 | 2.46 | .001 | 51% | |||

| Neutrality in calculating the compensation | Before 2015 | 4.82 | 1.50 | .001 | 14% | People whose compensation value was calculated by an independent valuer | |

| After 2015 | 4.25 | 2.39 | .001 | 24% | |||

| Procedural, recognitional and redistributive | Negotiation on compensation option | Before 2015 | 2.63 | 1.16 | .001 | 0% | People who negotiated compensation option |

| After 2015 | 2.33 | 1.54 | .001 | 0% | |||

| Participation in valuation | Before 2015 | 2.57 | 1.21 | .001 | 0% | People who participated in calculating the compensation | |

| After 2015 | 2.30 | 1.51 | .001 | 0% | |||

| Valuation and compensation at market prices | Before 2015 | 4.93 | 1.41 | .001 | 18% | People whose compensation was calculated at market prices (First valuation) | |

| After 2015 | 4.91 | 1.74 | .001 | 14% | |||

| Satisfaction with compensation | Before 2015 | - | - | - | 18% | People who are satisfied with compensation at first valuation | |

| - | 39% | People who are satisfied with compensation after counter-valuation (good trends through increase in the level of satisfaction) | |||||

| After 2015 | - | - | - | 14% | People who are satisfied with the compensation at first valuation | ||

| - | 48% | People who are satisfied with the compensation after counter-valuation (good trends through increase in the level of satisfaction ) | |||||

| Redistributive | Access to other properties using the compensation | Before 2015 | - | - | - | 8% | People who afford other properties in the close neighbourhoods |

| After 2015 | - | - | - | 9% | |||

| Year | Reference Price (average) | Market Prices | Difference | Sig. | Reference Price (maximum) | Market Prices | Difference | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 5.40 | 9.72 | 4.32 | .054 * | 8.22 | 9.72 | 1.49 | .697 |

| 2018 | 5.40 | 12.16 | 6.76 | .002 ** | 8.22 | 12.16 | 3.93 | .116 |

| Expropriation Period | Range of the Compensation Value in USD (Based on First Valuation) | Number of Appeals | Geometric Mean of the Value in USD | Increase in % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Valuation | Counter-Valuation (Paid Compensation) | ||||

| Before 2015 | Less than 1000 | 6 | 781.99 | 1004.22 | 20.49 |

| 5000–10,000 | 6 | 7923.99 | 13,385.50 | 68.03 | |

| 10,000–20,000 | 5 | 16,471.56 | 22,722.76 | 34.38 | |

| 20,000-30,000 | 15 | 24,709.11 | 33,219.55 | 32.30 | |

| 30,000–40,000 | 7 | 33,456.34 | 42,005.80 | 22.06 | |

| 40,000–50,000 | 2 | 46,882.59 | 70,608.46 | 50.61 | |

| All ranges | 41 | 11,553.48 | 15,630.64 | 30.53 | |

| After 2015 | Less than 5000 | 2 | 4514.52 | 6874.68 | 51.97 |

| 5000–10,000 | 12 | 7806.85 | 12,763.12 | 59.92 | |

| 10,000–20,000 | 4 | 14,972.34 | 24,744.26 | 64.42 | |

| 20,000–30,000 | 14 | 25,364.95 | 41,606.01 | 63.47 | |

| 30,000–40,000 | 14 | 32,900.06 | 52,057.74 | 56.52 | |

| 50,000–60,000 | 2 | 54,533.80 | 80,913.70 | 47.78 | |

| 60,000–70,000 | 4 | 65,311.44 | 96,541.82 | 46.52 | |

| All ranges | 52 | 20,629.50 | 33,016.14 | 58.25 | |

| Location | Number | Mean Value for Compensation | Mean Prices for New Property | Correlation Coefficient | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9 | 23,207.04 | 20,920.45 | .695 * | .038 |

| 2 | 29 | 26,467.37 | 29,580.45 | .884 ** | .001 |

| 3 | 33 | 20,300.46 | 16,705.15 | .923 ** | .001 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uwayezu, E.; de Vries, W.T. Expropriation of Real Property in Kigali City: Scoping the Patterns of Spatial Justice. Land 2019, 8, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020023

Uwayezu E, de Vries WT. Expropriation of Real Property in Kigali City: Scoping the Patterns of Spatial Justice. Land. 2019; 8(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleUwayezu, Ernest, and Walter T. de Vries. 2019. "Expropriation of Real Property in Kigali City: Scoping the Patterns of Spatial Justice" Land 8, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8020023