1. Introduction

The incorporation of roughness elements in waterways is an effective approach to modifying flow patterns and enhancing energy dissipation. One of their most common applications is in hydraulic jumps, where they help achieve comparable or improved performance within a shorter basin length [

1,

2,

3], a practice dating back to the 1950s [

4]. Hassanpour et al. [

5] investigated lozenge-shaped roughness elements in a stilling basin with lateral expansion and found that this configuration reduces the required tailwater depth for hydraulic jump formation. Another widely studied roughness form is bed corrugation, tested in various configurations [

6,

7]. Model studies by Izadjoo and Shafai-Bejestan [

8] demonstrated that compared with a smooth bed, trapezoidal corrugations decrease the conjugate tailwater depth by about 20% and the jump length by 50%. Similarly, Abbaspour et al. [

9] examined sinusoidal corrugations with different steepness ratios, showing that the bed shear stress is approximately ten times higher than on a smooth surface, leading to greater energy dissipation. In numerical simulations by Ghaderi et al. [

10], three roughness geometries—triangular, square, and semi-oval—were analyzed, indicating that roughness elements reduce the relative maximum velocity in submerged hydraulic jumps, with the triangular shape being the most effective in shortening jump length. Evcimen [

11,

12] further investigated prismatically shaped roughness elements, extending the understanding of their hydraulic behavior.

In the construction of low-head dams, gabions are often employed to form stepped chutes that promote effective energy dissipation [

13,

14,

15,

16]. With the advancement of roller-compacted concrete (RCC) technology, stepped spillways have become a common type of flood-release structure in large dams. To reduce unit discharge, the chute width can be substantially increased—sometimes extending nearly the entire dam length. The steps act as distinct roughness elements that modify pressure distributions, enhance air entrainment, and improve energy dissipation while reducing cavitation risk. The effects of baffles and sills on stepped chutes have been widely examined [

17,

18,

19,

20], showing that baffle-edged chutes dissipate more energy than sill-edged ones, and that shifting baffles or sills away from sharp edges leads to reduced energy dissipation. Moreover, parameters such as step chamfering, cavity blockage, step-face inclination, and step planform significantly influence flow patterns and turbulence structures, thereby affecting energy dissipation efficiency [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The stepped concept has also been adapted for embankment dams with mild downstream slopes [

29,

30,

31]. Depending on the unit flow and water head, cellular concrete blocks are sometimes employed. Precast wedge-shaped blocks provide step-overlay protection, combining efficient energy dissipation with high stability under high-velocity flow conditions.

Each of these topics has been the focus of extensive research, and the related literature is virtually innumerable. The introduction of a roughened bed can eliminate the need for a costly stilling basin or significantly reduce its length, resulting in a more efficient and streamlined design. More generally, a stepped spillway can be regarded as a form of baffled chute, although the geometry of its steps may vary. One of the most widely adopted designs is the Bureau of Reclamation type IX chute spillway, which incorporates impact baffle blocks [

32]. The Maple River spillway, for instance, includes twelve rows of baffle blocks, while similar configurations are found in numerous low-head dams across the United States [

33]. In contrast, the Yeoman Hey spillway in the United Kingdom features staggered rows of block baffles extending along the entire chute (

Figure 1a). Each row comprises five or six baffles, contributing to substantial energy dissipation [

34].

Robles et al. [

35] investigated the use of staggered rows of vertical pipes in a diverging chute spillway to dissipate energy and reduce flow velocities to acceptable levels. These vertical risers additionally serve to supply air to offset aerators. In experiments conducted by Nugroho et al. [

36], multiple rows of cubical blocks were installed on a 45° overflow apron immediately downstream of the spillway threshold. The blocks were evenly spaced along the chute, with variations in both lateral and streamwise spacing. Their results indicate that optimal energy dissipation occurs when the flow depth equals the block height, and that the presence of a baffled chute leads to a shorter hydraulic jump length. For stilling basins preceded by a roughened chute, Stojnic et al. [

37] examined the influence of steps on the flow, revealing that due to reductions in terminal energy, the design principles for such basins differ significantly from those applied to smooth chutes (

Figure 1b).

The chute is a critical component of a spillway and can be constructed directly on high-quality bedrock. In such cases, the natural roughness of the rock affects floodwater flow and may reduce the required size of an energy dissipator, if one is present [

4,

35,

38]. However, the deliberate incorporation of artificial roughness—whether on bedrock or on a concrete-lined chute bed—is less common than its use in energy dissipators.

In Sweden, updated flood criteria require many existing spillways to accommodate design discharges higher than those for which they were originally constructed. Statistics show that revised design floods are typically 20–50% greater than previous values [

39]. Managing this additional flow energy poses a significant challenge. Expanding an energy dissipator is often costly, and construction difficulties further limit modifications in existing structures.

Many Swedish spillways feature long chutes whose primary function is to simply convey water. Their slopes are usually gentle, below 3.5–7%. Introducing roughness along the chute bed could help dissipate a portion of the energy before the water re-enters the river, providing a potential alternative to enlarging energy dissipators. However, studies of roughened chutes remain limited, an observation echoed by Tullis and Bradshaw [

33]. With the successful application of straight roughness beams in a Swedish spillway [

40], to explore more effective roughness shapes is the motivation of this study. Several configurations—both straight and cranked—have been designed as roughness appurtenances for chute energy dissipation. Laboratory experiments were conducted to evaluate the performance of these configurations. The effect of the roughened chutes on energy losses was assessed in comparison with a smooth chute. Additionally, head losses along the chute were compared with those of the preceding energy dissipator. This study aims to provide guidance for the design of roughened chutes in low-head spillways.

2. Configuration of Roughness Elements

As part of a spillway upgrade, eight rows of roughness elements were installed in the existing chute to promote more uniform flow distribution across the cross-section and enhance energy dissipation [

40]. The spillway comprises seven gated openings, with a chute ~63 m long and a 3.8% slope. The roughness elements are straight concrete beams, each 0.5 m wide and 0.4 m high.

Figure 2 illustrates the baffled chute and the flow pattern during a low flood. With the inclusion of these elements, the terminal energy at the new design flood—~40% higher than the previous one—remains at a comparable level. With certain simplifications, the model in this study is partially derived from this prototype spillway. Froude similarity is used, and the model scale is approximately 1:18.

Referring to this installation with straight ribs, three labyrinth roughness configurations were developed (

Figure 3). The design follows these principles:

- ○

Each configuration has a rectangular cross-section with width T = 20 mm and height D = 21 mm, corresponding to the dimensions of the available wood product.

- ○

Regardless of the roughness type, each unit is symmetrical along its streamwise axis and maintains consistent dimensions in both streamwise (S) and spanwise (W) directions. The adopted unit size is S = 70 mm and W = 114 mm, with the spanwise dimension chosen to fit ten units across the chute width.

- ○

The triangular units with an angle of α ≈ 52.0°.

- ○

The trapezoidal units with an angle of α ≈ 26.4°. The edge facing up- and downstream is 2.0 × W2 = 44.6 mm.

- ○

The rectangular units. Their edge facing up- and downstream is 2.0 × W2 = 77.0 mm.

The chosen wood is aspen, relatively dense to resist water. To ensure uniformity and high quality, all elements were manufactured using a waterjet cutting machine (

Figure 4). Quality control measurements confirmed that geometric deviations for each unit remained below 0.3–0.5 mm.

3. Experimental Setup

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the layout of the experimental rig. The spillway model, with a width of

B = 114 cm, is placed at the lower end of the flume, measuring 11.0 m long, 2.0 m wide, and 2.0 m high. The overflow crest length is

L =

B = 114 cm. Water is supplied to the model through a Ø250 mm inlet pipe. A flow barrier is installed near the downstream end of the inlet to suppress turbulence. In the middle of the flume, a straight channel with a streamlined entrance, matching the crest width, is also provided.

The model is constructed from water-resistant plywood with a fairly smooth surface (with micro-evenness) and has a total length of 420 cm, including a 280 cm chute section. Its dark surface is coated with light gray paint to enhance visibility for photography and observation. The chute’s downstream end is set at elevation +0.0 cm, while the spillway crest is at +50 cm. The flume bed is positioned

H0 = 25.0 cm below the crest, featuring a 90° upper corner and a 5.4 cm radius at the lower corner. A 90.0 cm long stilling basin precedes the chute. With its upper end at +12.5 cm, the chute itself has a 4.5% slope. In this study, the use of this gentle slope is mainly based on the Swedish conditions. Steeper chutes are not discussed.

Figure 7 shows the chute layout with each of the configurations.

For each roughness type, ten rows of roughness elements were installed along the chute, with the first row positioned 40.0 cm from the upper end and the last row 60.0 cm from the lower end (measured at the row centerlines). Each row consists of 10 units (width 10 × W) for the cranked shapes, covering the entire chute width. The centerline spacing between consecutive rows is 20.0 cm (10 × T). The elements were painted in different colors to aid identification.

In the inlet pipe of the rig, a calibrated magnetic flow meter measures the flow rate (accuracy better than 0.2%). The water level measured 3.0 m upstream of the crest, labeled as section 0 (

Figure 5a), is used to calculate the water head (

H) and specific energy (

E0). At this section, the flume bed elevation is

Z0 = 0.25 m. Point gauges are employed for estimating cross-sectionally averaged water depths (

h) within the chute. A standard laboratory setup is used, featuring a plastic tube from a measurement point on the floor leading to a panel with an 8 cm measurement tube, in which a point gauge is placed, with an accuracy of better than 0.2 mm. Along the chute, two key sections are defined: an upstream section (u), located 29 cm from its upper end, and a downstream section (d), located 29 cm from its lower end (see

Figure 5c). Water depths at these sections are labeled as

hu (upstream) and

hd (downstream), calculated as the average of measurement results taken at 12 points across the chute. At each point of either cross-section, repeated measurements are made to minimize errors, and its water depth represents a time-averaged value. Key flow parameters include flow rate, flume water level, and flow velocity and depth within the chute. Flow patterns are documented using photographs and video recordings. Because the chute contains ten discrete rows of macro-roughness elements, the flow along the 2.8 m chute does not reach a classical fully developed state in which velocity and shear-stress distributions become invariant in the streamwise direction.

4. Results and Discussions

Owing to the accurate construction of the model, the flow remains uniform across the cross-section from upstream to downstream. Energy losses in a smooth chute are examined first, followed by those in the straight and cranked types. For each chute type, several flow rates are tested, namely, H ≈ 7.5, 10.0, 12.5, 15.0, and 18.6 cm. Preceded by the basic flow features, observations and analyses are presented below.

4.1. Basic Flow Parameters

Froude and Reynolds numbers are defined as F = and R = , where V = cross-sectional average of flow velocity, Rh = hydraulic radius, g = gravitational acceleration, ρ = density of water, and μ = dynamic viscosity of water. Within the examined flow range, their values in the upstream flume are F = 0.03–0.07 and R = (1.9–6.9) × 104.

The free-surface flow (

Q) over an overflow weir is expressed as

where

C = discharge coefficient.

Figure 8 plots its

H-

Q relationship. Within the examined

H range,

Q = 35–140 L/s, and

C = 1.47–1.55.

For the smooth chute, the streamwise variations of water depth

h at the locations where roughness elements are to be installed are shown in

Figure 9. In the absence of roughness, the chute’s water surface is relatively smooth and undisturbed, exhibiting only minor perturbations even at high water heads (e.g.,

H = 15.0 and 18.6 cm). Within the examined

H interval, the average flow velocity (

V) is

Vu = 1.0–1.4 m/s at section u and

Vd = 1.5–2.1 m/s at section d. The corresponding R range is 3.0 × 10

4–1.1 × 10

5. If R > 10

5, then the viscous effect is negligible [

42]. Obviously, the results are somewhat affected by the viscous force.

4.2. Flow Patterns with Roughness Elements

The roughness protrusions significantly alter the local flow structure, with the magnitude of these changes depending on the flow rate. To quantify their effects, water depths at the roughness elements are compared with those in a smooth chute.

Figure 10 shows the water depth

h at the 1st and 10th rows for the triangular elements, while

Figure 11 presents the streamwise

h-profiles for the trapezoidal shapes. Due to surface fluctuations, the profiles represent averaged measurements. The other cranked elements exhibit similar

h variations. The plots do not mirror the slightly smaller water depths between adjacent rows. These results can be compared with those in

Figure 9. Clearly, the presence of roughness, regardless of shape, leads to a substantial increase in water depth.

All the labyrinth elements exhibit similar results of water depth. With a 4.5% chute slope, the flow accelerates and the water depth decreases progressively downstream. The roughness clearly leads to a substantial increase in water depth—by a factor of 2.5 to 3.0 at low flows (

H ≤ 12.5 m) and 1.7 to 2.1 at high flows (

H > 12.5 m). Unlike flows in the smooth chute, the streamwise water surface exhibits noticeable fluctuations, typically varying within 0.5–1.0 cm along the row centerline, depending on flow rate and roughness type.

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 show the flow patterns at

H ≈ 7.5 and 15.0 cm, respectively.

For the straight layout, the free-surface perturbations in the streamwise direction are readily noticeable at low water heads (e.g., H < 10.0–12.5 cm). Across each row, a solitary ripple with a distinct crest and steep flanks appears. The flow is essentially two-dimensional, with negligible lateral variation. As the flow rate or chute water depth increases, these solitary ripples gradually become smeared.

All three labyrinth (cranked) configurations exhibit similar behavior, with little distinction between them. At low flow rates (e.g., H < 10.0 cm), a solitary hump forms across each element row. Each hump features a somewhat diffused crest with a leading and trailing edge, most pronounced for the rectangular shape. Owing to the streamwise element dimension (S) being larger than that of the straight type, the crest is observed to be flatter and longer in the flow direction. The cranked shapes also promote lateral flow diffusion in the cross-section. At higher flow rates, the humps blur, and water-surface fluctuations become less pronounced.

The roughness elements are oriented vertically and have a rectangular crest in cross-section. At low heads, the flow over these elements resembles that over a labyrinth weir or spillway, differing mainly in scale [

43]. Each unit within a row exhibits overflow characterized by an interference region—where nappes collide—and submergence. Within the examined flow range, the water surfaces over both straight and cranked shapes are never as smooth as in the smooth chute. However, when the chute water depth satisfies

h/

D > 6.5–7.0, the influence of the elements on the surface flow becomes negligible.

4.3. Energy Losses

When a bluff protuberance is introduced in the chute, it disrupts the smooth flow, generating flow separation, recirculation zones, and a pressure drop. This disturbance alters the flow structures and enhances turbulent mixing. As a result, additional head losses occur due to increased friction and flow resistance. At the 0, u, and d sections, the specific energies—denoted as

E0,

Eu, and

Ed—are used as proxies to quantify energy losses within the waterway. The definitions of these variables are listed in

Table 1.

Figure 14 illustrates the difference in specific energy,

E0 −

Eu, between sections 0 and u, representing the total energy loss from the reservoir to the start of the chute. The stilling basin accounts for the majority of this loss. This energy difference increases slightly with increasing head

H. For a given flow rate,

Eu remains essentially constant, as confirmed by measurements at 12 positions across the chute in repeated tests. The energy loss along this portion of the waterway is independent of the roughened chute. However, small measurement errors lead to some discrepancy in the results.

The energy loss caused by the roughened chute itself is

Eu −

Ed, and the energy dissipation efficiency is defined as

Figure 15 compares the variations of

Eu −

Ed with

H and

χ with

H/

H0. In the smooth chute, head loss is dominated by the surface friction of the plywood, which serves as a reference for evaluating the roughness appurtenances. For each roughness configuration, energy loss gradually decreases with increasing water head. This indicates that at shallow flow depths, the roughness intrusions affect the entire flow depth, resulting in high dissipation efficiency.

Compared to the smooth chute, the straight ribs exhibit significantly higher energy dissipation efficiency. Although the energy loss decreases with increasing H, the difference relative to the smooth chute becomes more pronounced. For instance, the dissipation efficiency differs by a factor of 38.3%/20.2% = 1.9 at H/H0 = 0.30 and of 20.0%/5.3% = 3.8 at H/H0 = 0.75.

Relative to the straight elements, all labyrinth (cranked) shapes demonstrate even more effective energy dissipation. The trapezoidal shape yields slightly higher efficiency than the other two, although differences among the three cranked types are minor. On average, their efficiency enhancement ranges from 16% to 35% across the examined flow range.

4.4. Discussion

This study is conducted using fixed element sizes and row spacings. The element dimensions,

T = 20 mm and

D = 21 mm, correspond to an approximate prototype size of 0.4–0.5 m. The row spacing (10 ×

T = 20.0 cm) is based on, and scaled from, the prototype chute [

40], with slight modification. This spacing determines how each roughness row interacts with the flow from its upstream row, which in turn influences the energy dissipation between rows. For a given flow, it may be possible to identify an “optimum” spacing that maximizes dissipation efficiency; however, achieving this across a range of flows is unlikely. No tests were conducted in this regard. The highest head tested is

H = 18.6 cm, and beyond roughly

H = 20.0 cm, sweeping-out of the stilling basin would occur.

The performance of the labyrinth elements can be further evaluated from two perspectives. The first concerns the energy dissipated along the chute compared with that dissipated in the stilling basin. The second relates to the influence of the staggered arrangement of the elements.

Normalized by

E0, the following parameters are defined:

For the three cranked configurations,

Figure 16 plots the variations of

η1 and

η2 with

H/

H0. The

η1 curve primarily represents the energy dissipated in the stilling basin. The results highlight the contrast between the dissipation efficiencies of the basin and the roughened chute. The stilling basin usually serves as the major source of energy dissipation, while the chute plays a complementary role. However, if the chute is sufficiently long and more roughness elements are installed, the energy dissipated along the chute can become comparable to that of the stilling basin. Considering the ten cranked elements (of any given type) as one group and repeating this group downstream, the additional group dissipates even more energy than the first one, as the water depth gradually decreases and the flow velocity increases along the chute. Assuming that each added group dissipates the same amount of energy as the first, achieving the same overall energy dissipation as the stilling basin would require four to five groups depending on water head. In other words, in the absence of a stilling basin, a sufficient number of roughness rows could produce an equivalent dissipation effect.

In the preceding tests, the labyrinth elements of each type are arranged so that all rows are identical, without any lateral offset. Traditionally, isolated blocks or piers in a baffled apron (so-called impact dissipator) are arranged in a staggered configuration to enhance flow performance [

4,

32,

33]. Accordingly, supplementary tests are carried out to examine the influence of a staggered arrangement of the rectangular elements, in which all even rows are shifted by half the element width (0.5 ×

W) relative to the odd rows (

Figure 17a). The corresponding flow pattern at

H = 7.5 cm is shown in

Figure 17b.

Without any lateral offset, the streamwise spacing between the crests of adjacent rows remains constant, and the flow pattern is identical in cross-section over each row. The tests indicate that introducing a 0.5 ×

W offset modifies the flow pattern. As shown in

Figure 17b, the water surface along the right sidewall exhibits streamwise undulations, with a local dip (or depression) between two neighboring rows. However, the dip from odd to even rows (e.g., from row 1 to 2) extends farther than that from even to odd rows (e.g., from row 2 to 3). This streamwise pattern is repeated at each element unit in cross-section and is readily visible under low-flow conditions. As the discharge increases, the surface undulations gradually smooth out.

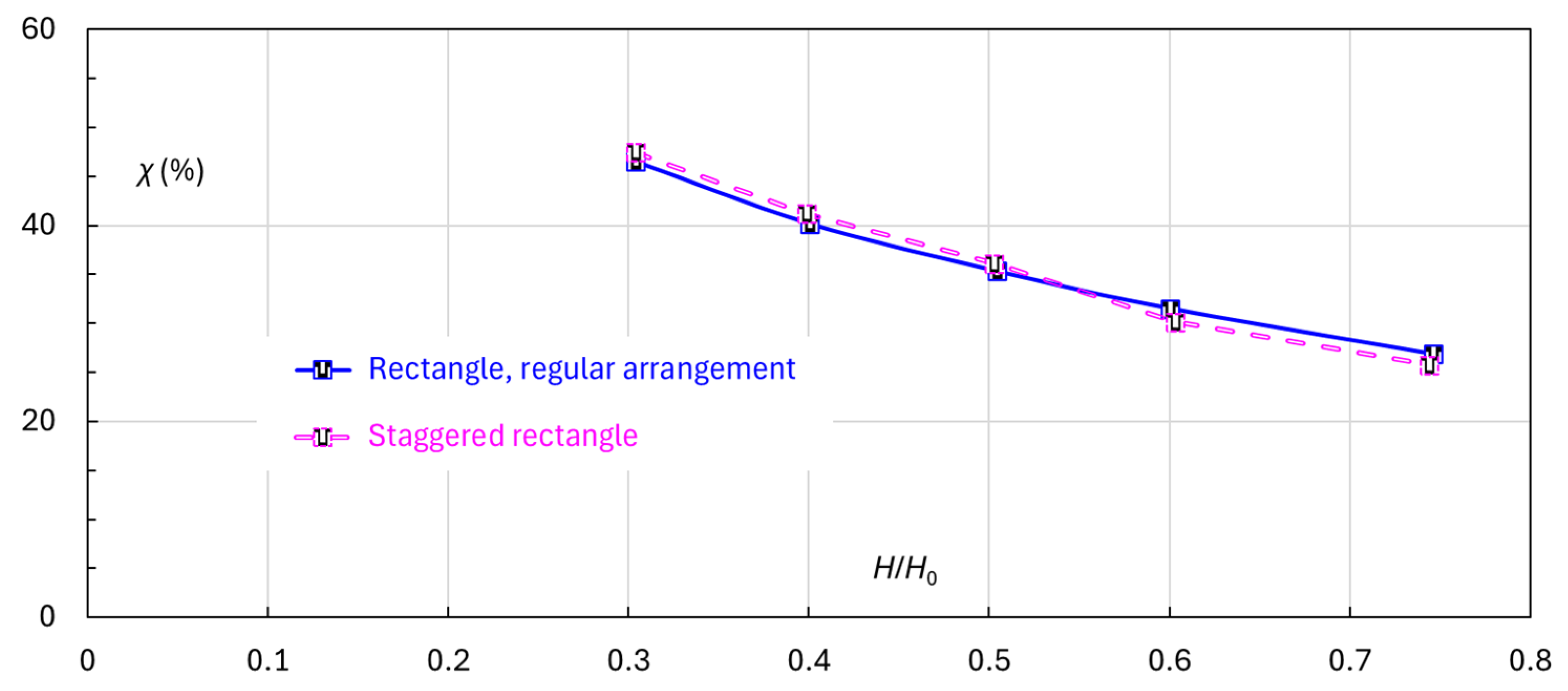

The corresponding

χ-values are presented in

Figure 18. Despite the modification in flow structure, the staggered arrangement results in negligible changes in energy loss, even at low flow rates.

5. Conclusions and Comments

Introducing roughness appurtenances in a chute is an effective method to reduce the terminal energy at its end and mitigate the erosion potential in the tailwater. This study is based on a prototype spillway with eight straight beams, which have functioned satisfactorily since installation. To enhance energy dissipation, one straight and three labyrinth (cranked) configurations—triangular, trapezoidal, and rectangular—were designed and manufactured with precision. The experiments aim to compare the efficiency of these roughness layouts at varying flow rates. The following conclusions can be drawn.

Compared to the chute without elements, the presence of roughness elements leads to a substantial increase in water depth, by a factor of 1.7–3.0 depending on the water head. At low flows, the flow over the periodic bed roughness of any type generates strong streamwise water-surface waviness. As the flow rate increases, these surface fluctuations gradually smooth out. When the chute water depth reaches 6.5–7.0 times the roughness height, the influence of the elements on the surface water nearly disappears, and the water surface becomes relatively smooth. This behavior is observed for both straight and cranked elements.

Compared to the smooth chute, the straight ribs profoundly augment energy dissipation efficiency, by a factor of 1.9–3.8 depending on water head. Within the examined flow range, the labyrinth configurations dissipate 16–35% more energy than the straight beams. However, the differences among the triangular, trapezoidal, and rectangular shapes are small. A staggered formation does not heighten the energy dissipation either. Introducing roughness on the chute is considered a complementary measure. However, if the chute is sufficiently long, an adequate number of roughness rows could replace the function of a stilling basin.

Roughness elements contribute to enhanced air entrainment in the flow. In a prototype, turbulence intensity is considerably higher than in the corresponding model, resulting in stronger air entrainment and higher actual energy dissipation efficiency. Roughness elements can also compensate for asymmetrical spillway or discharge conditions by redistributing the flow across the chute.

The use of roughness elements is recommended for spillway chutes with gentle slopes, typically less than 5–6%, and a water head preferably below 12–15 m. Higher heads may be acceptable if an energy dissipator is installed upstream of the chute. Compared to a smooth chute, a roughened chute produces a greater flow depth, requiring higher sidewalls. In prototype applications, the width and height of individual roughness elements generally range from 0.4 to 0.5 m, with row spacing approximately ten times the element width.

This study is limited to gentle chute slopes. Their use in steeper chutes might be practicable, as long as resulting splash and spray are contained or the discharge safety is ensured. Any proposed design should be validated through hydraulic model studies, considering factors such as chute slope, roughness dimensions, water-head range, sidewall height, and other relevant parameters. Drainage holes or slots should be incorporated to facilitate dewatering and prevent ice formation during winter.