Geochemistry of Water and Bottom Sediments in Mountain Rivers of the North-Eastern Caucasus (Russia and Azerbaijan)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

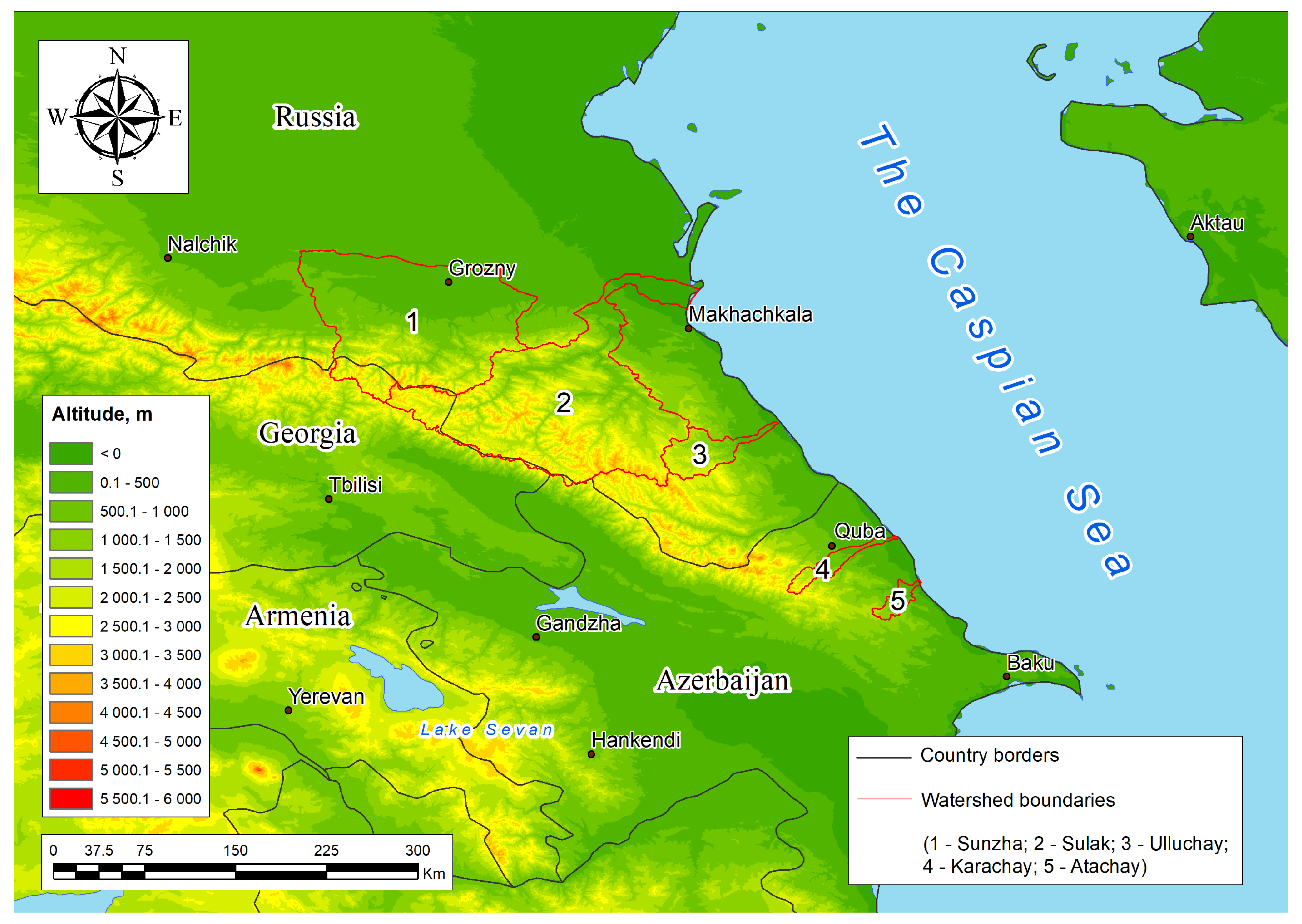

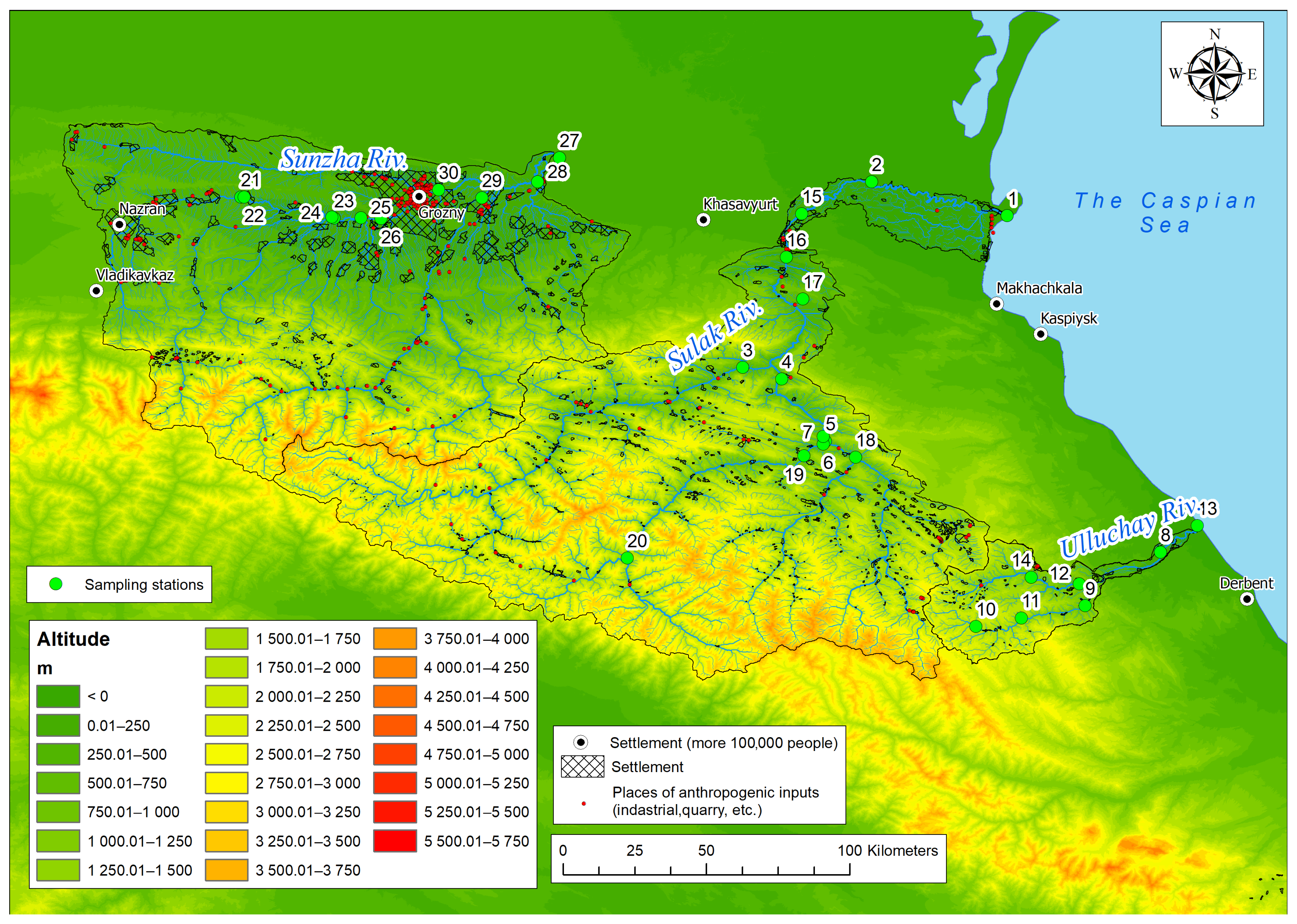

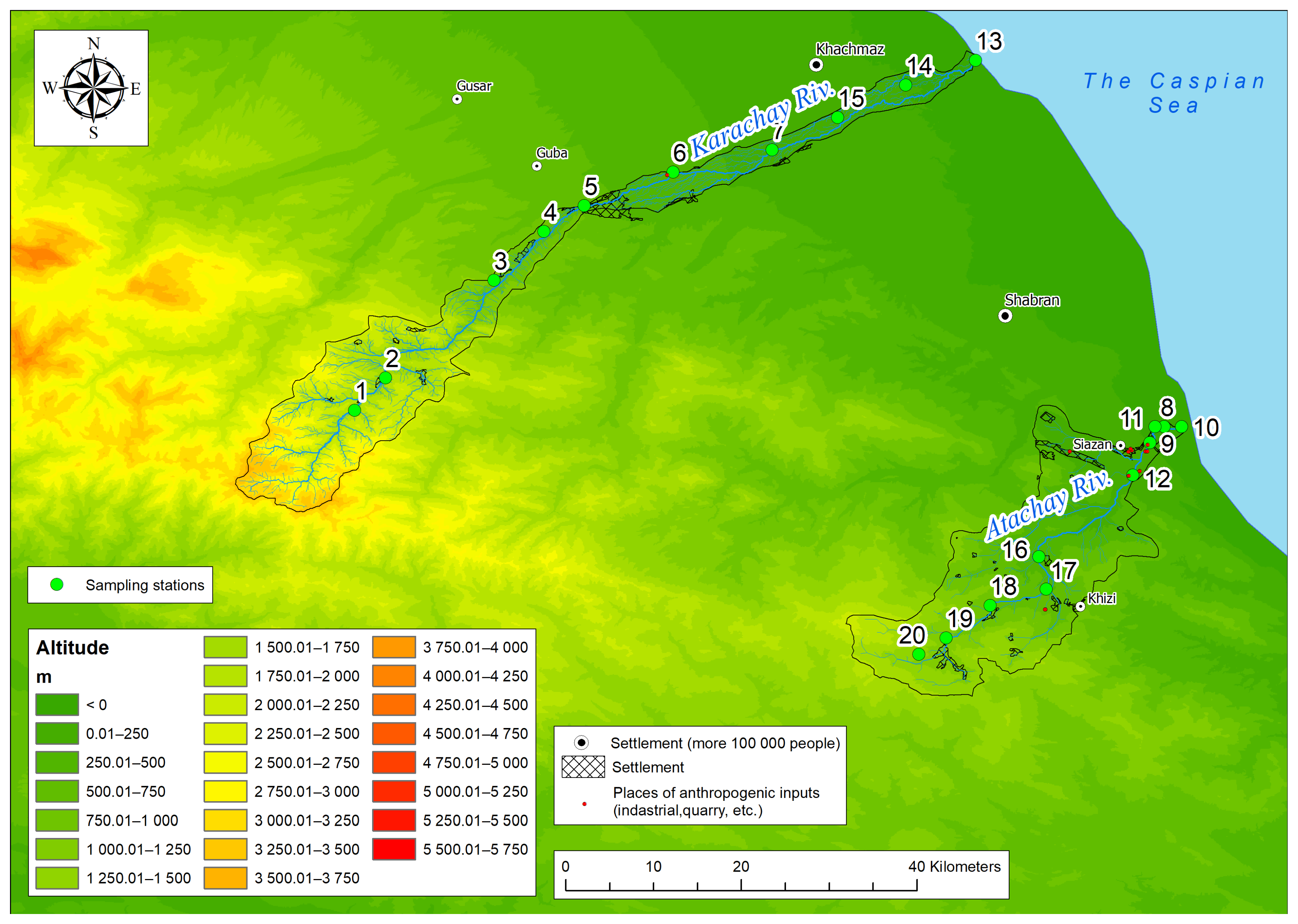

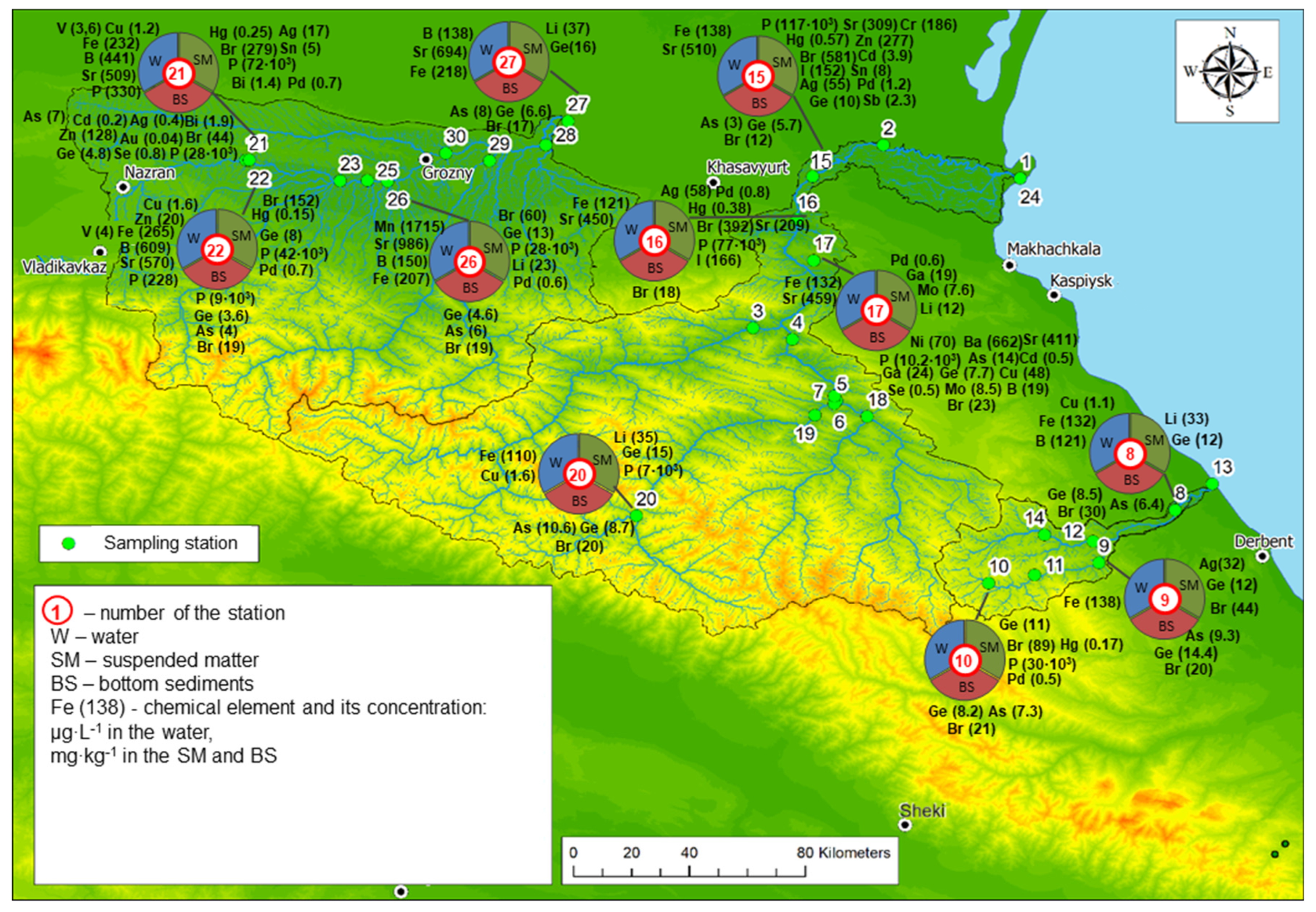

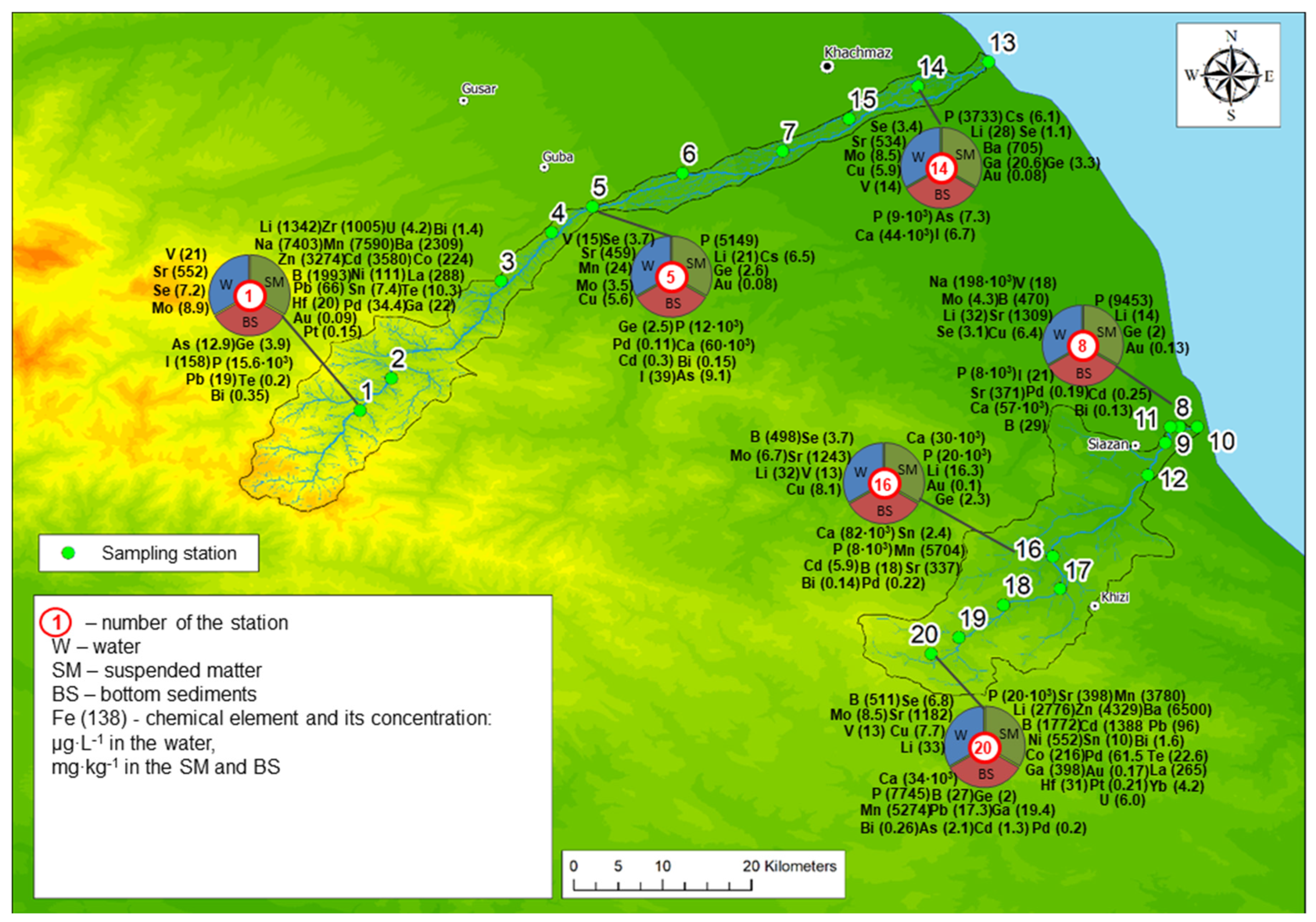

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Strategy

2.3. Analytical Procedures

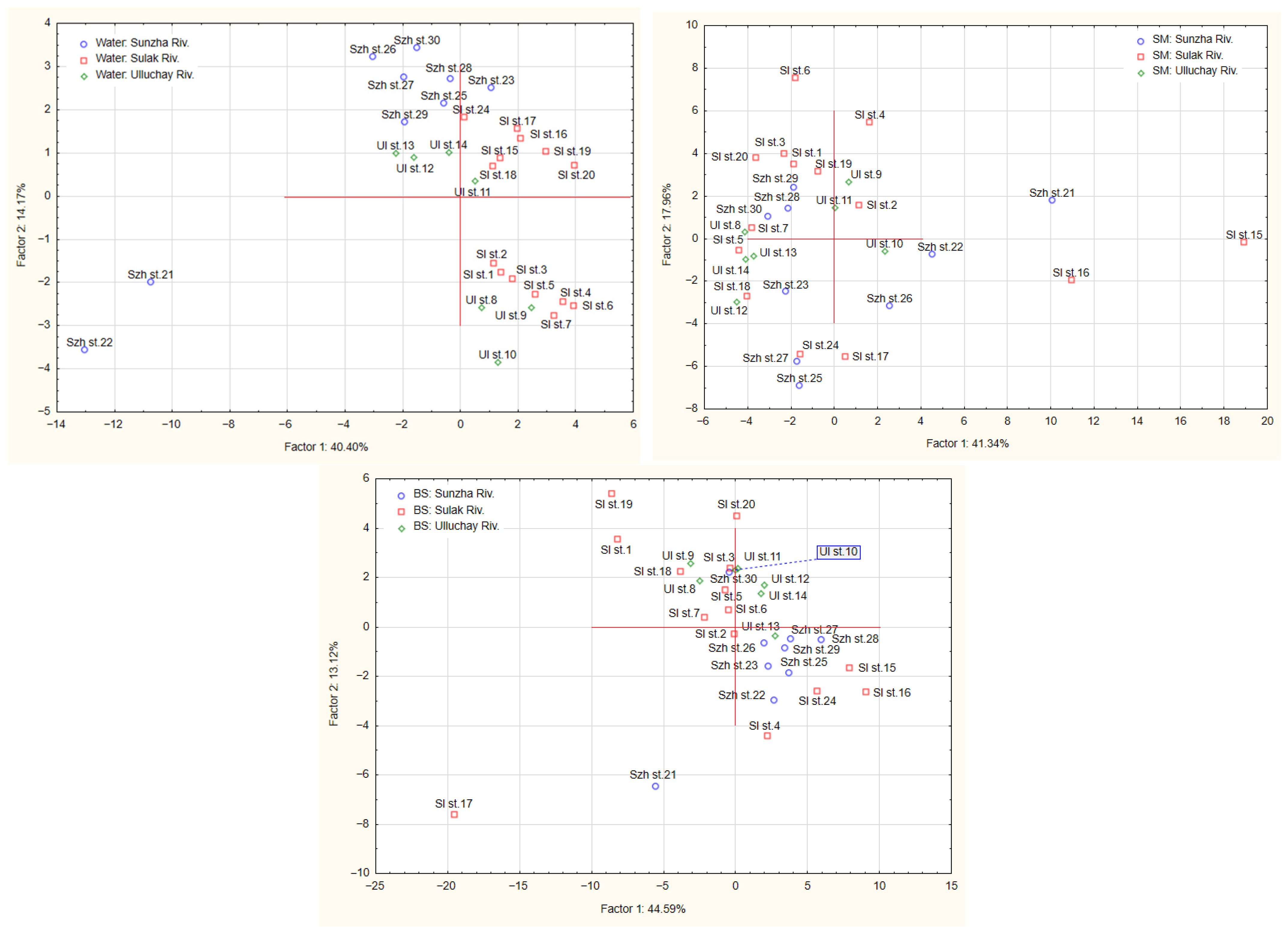

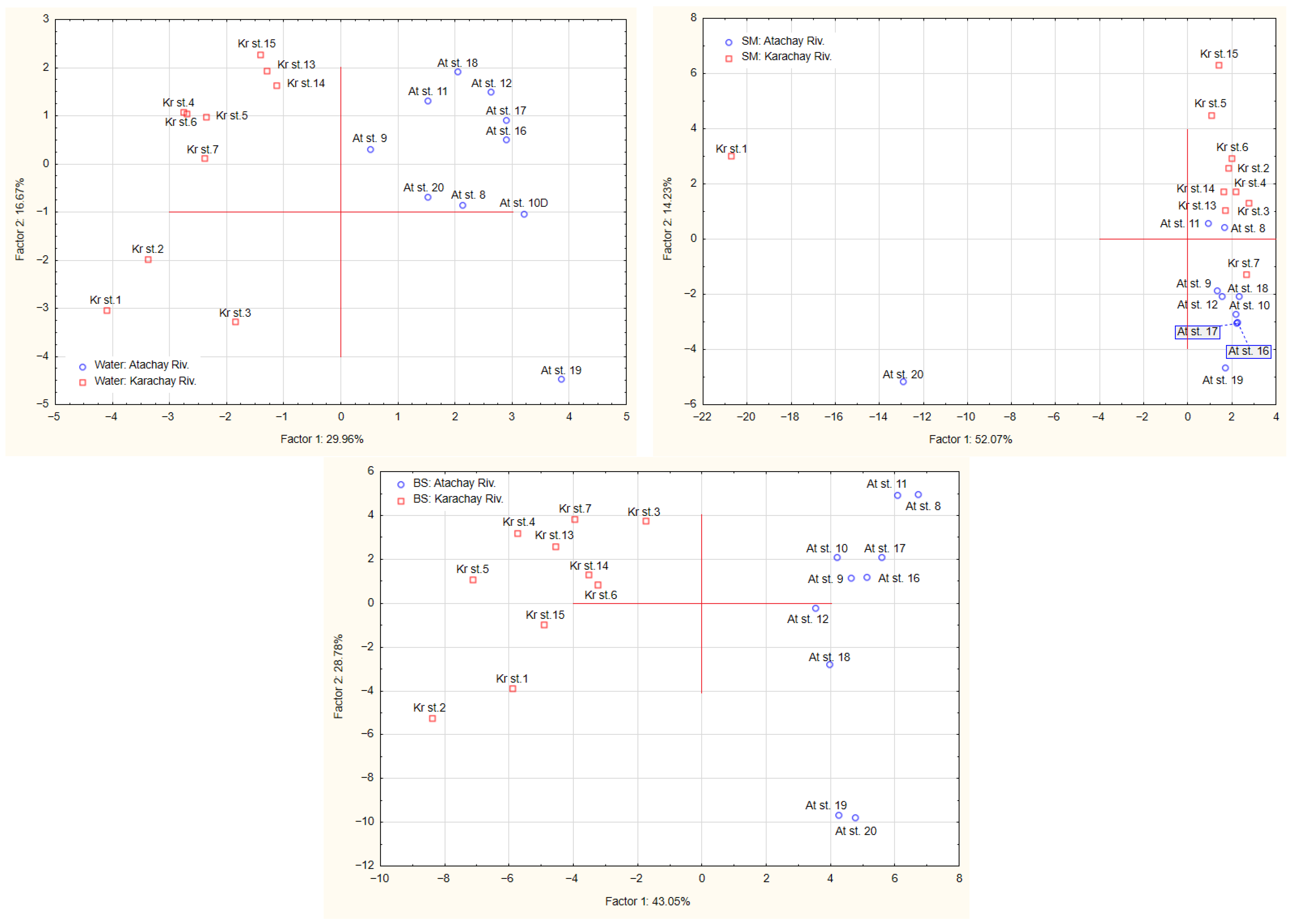

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

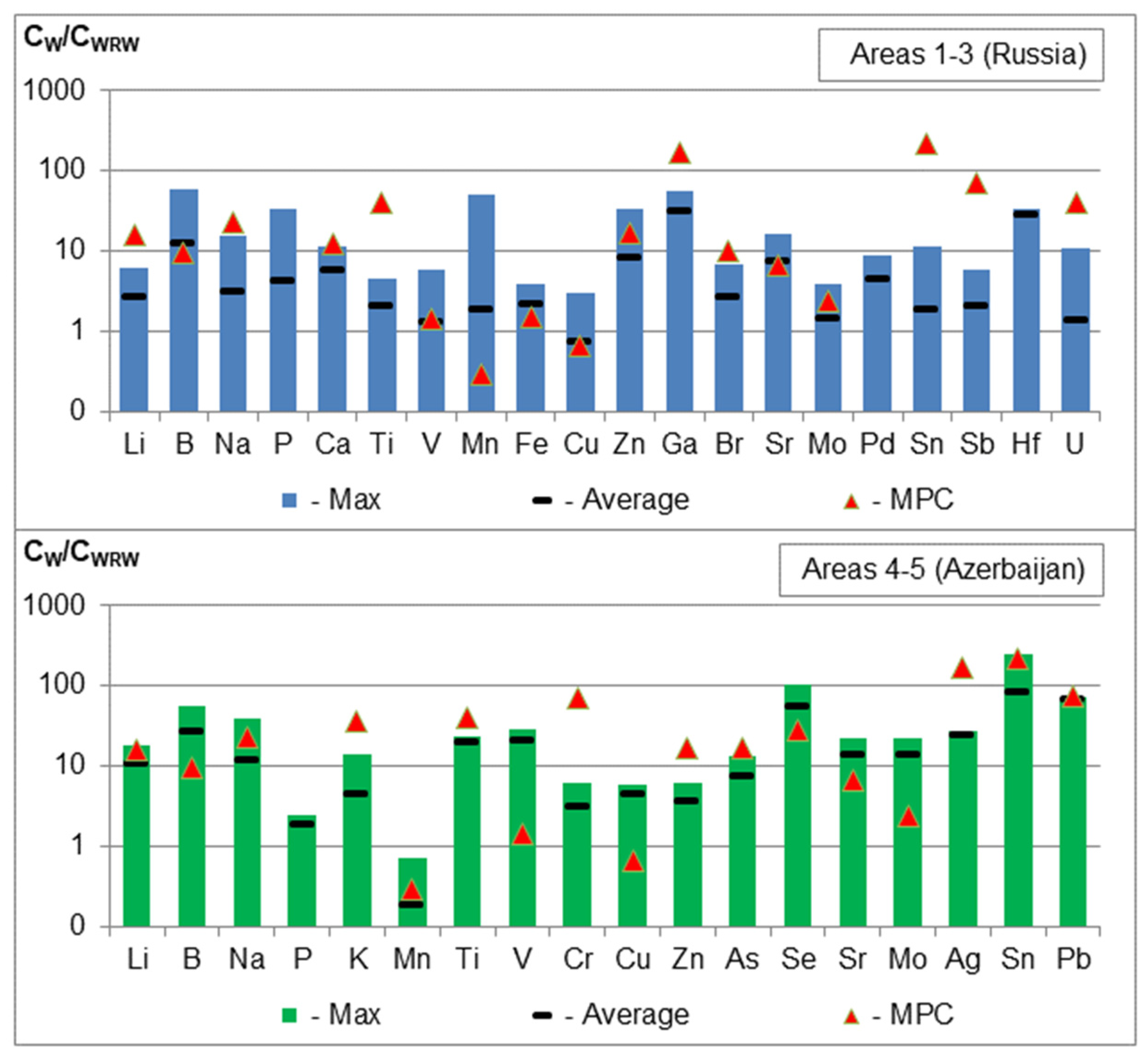

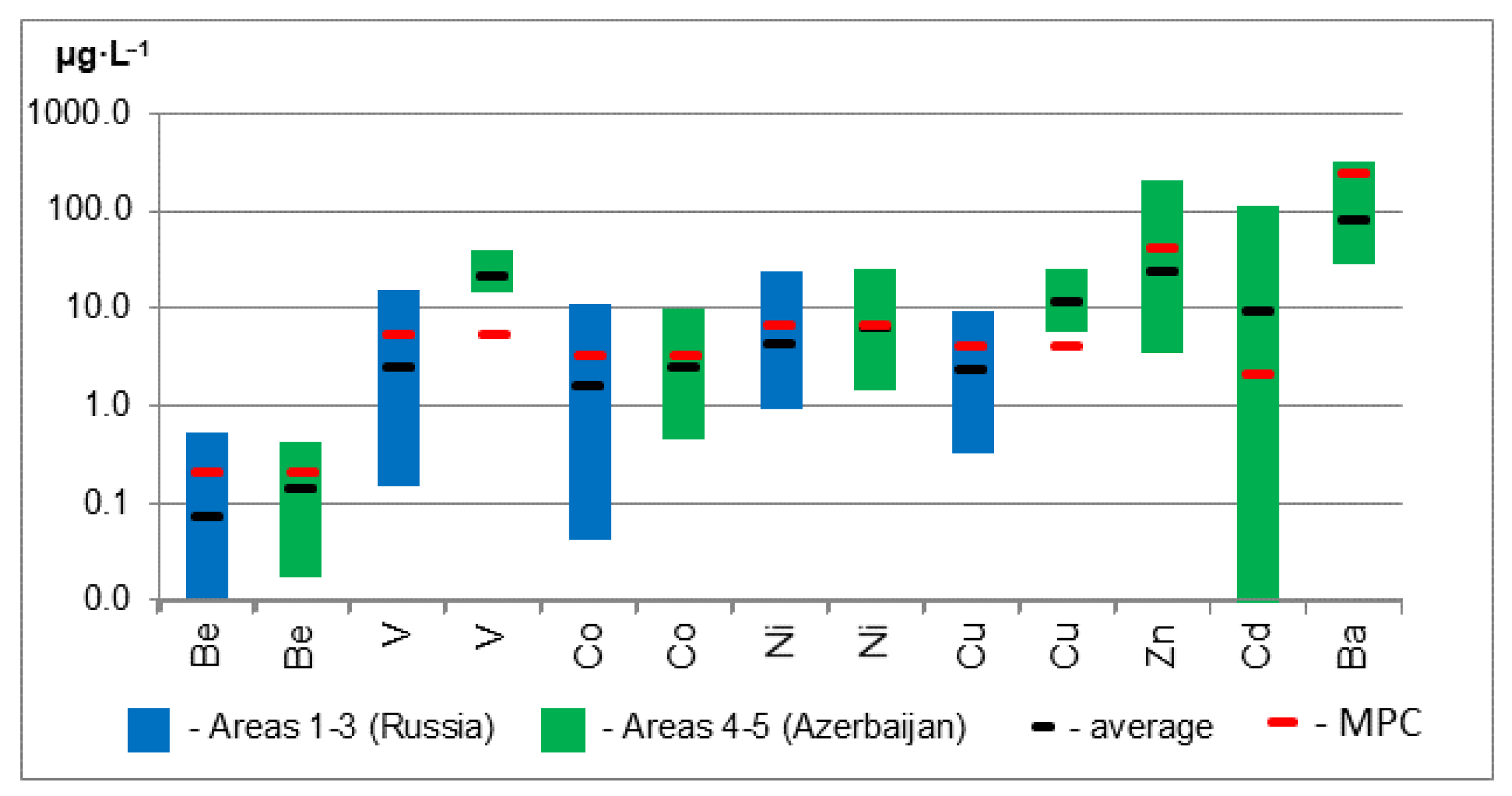

4.1. Dissolved Trace Elements in Mountain River Waters

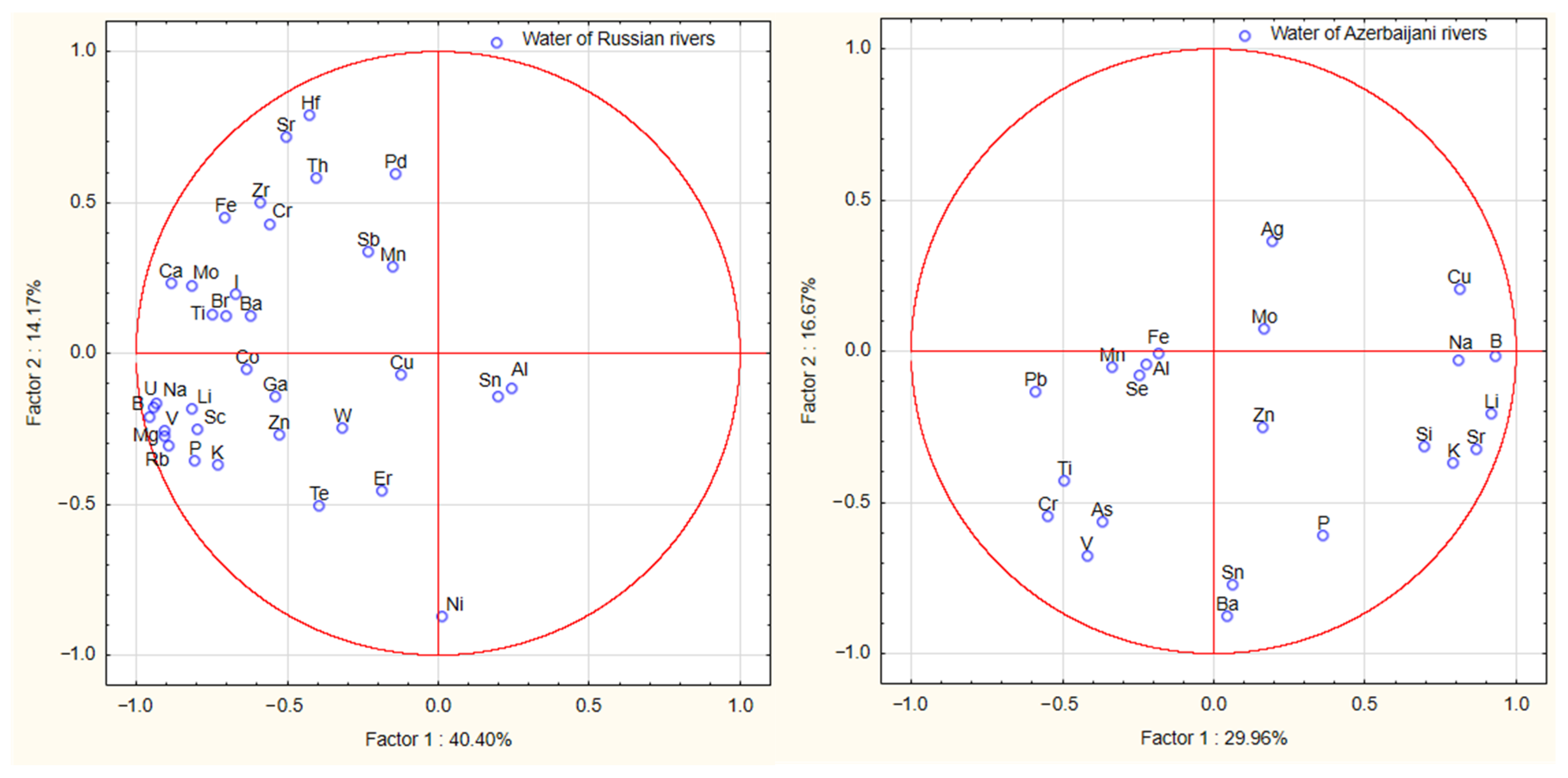

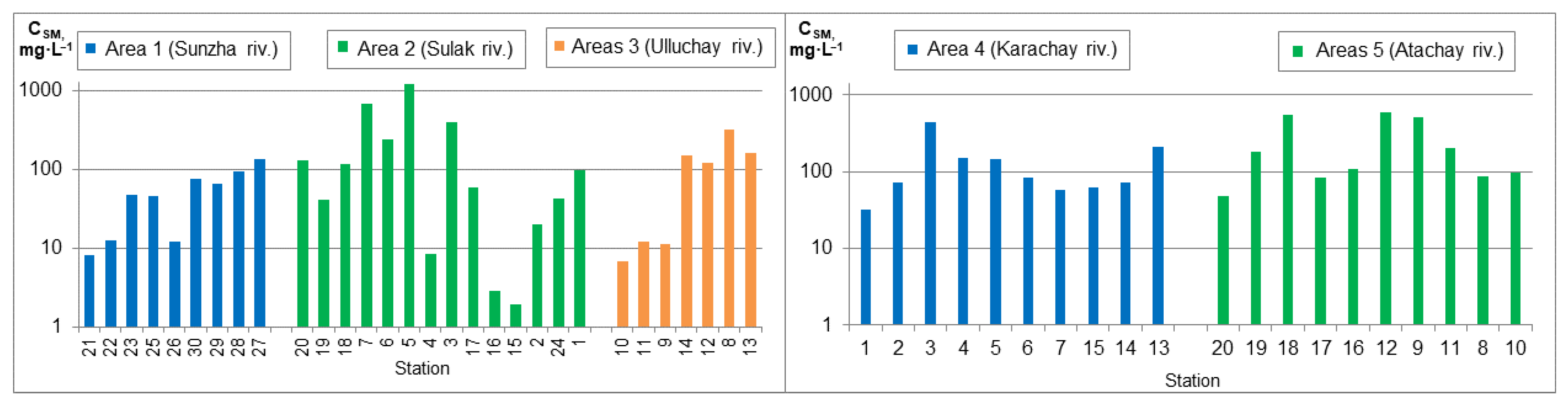

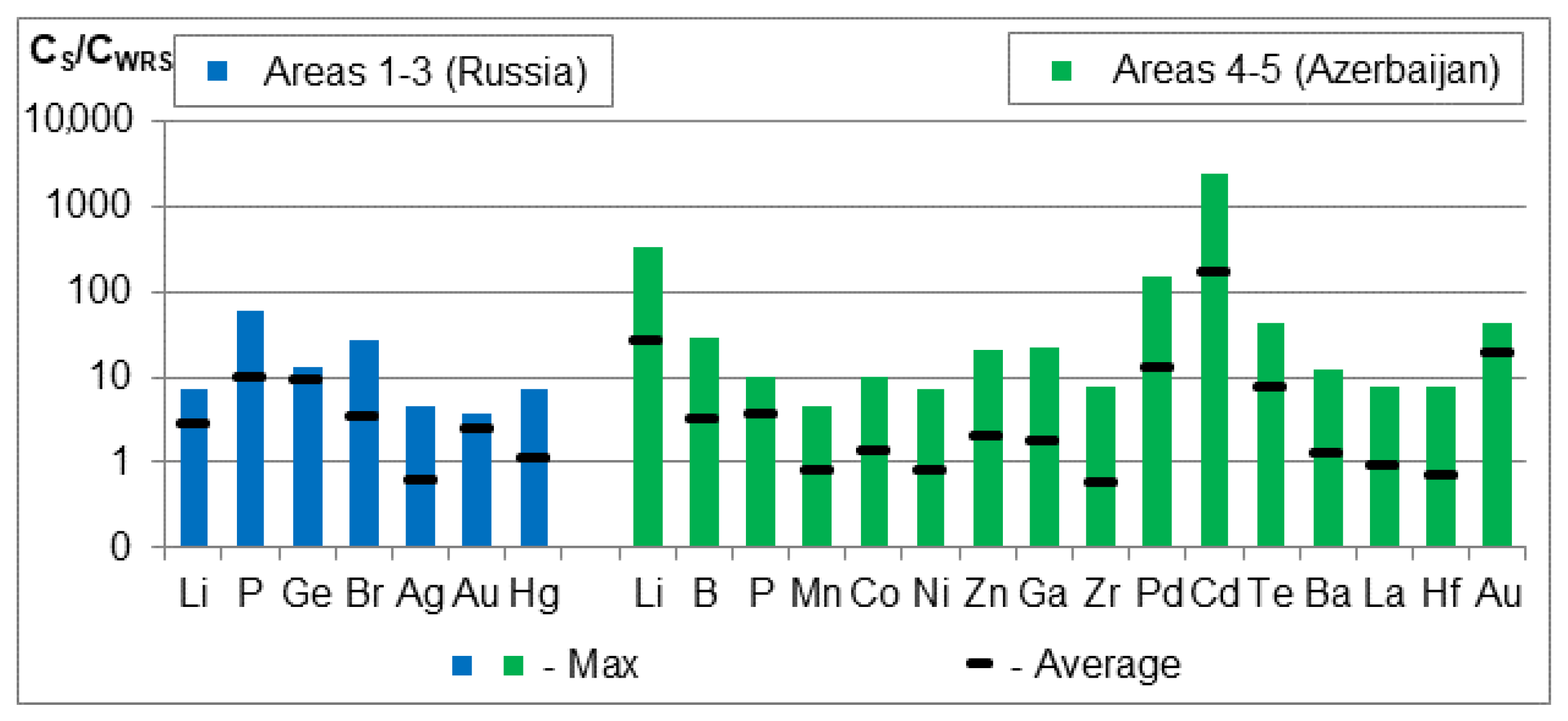

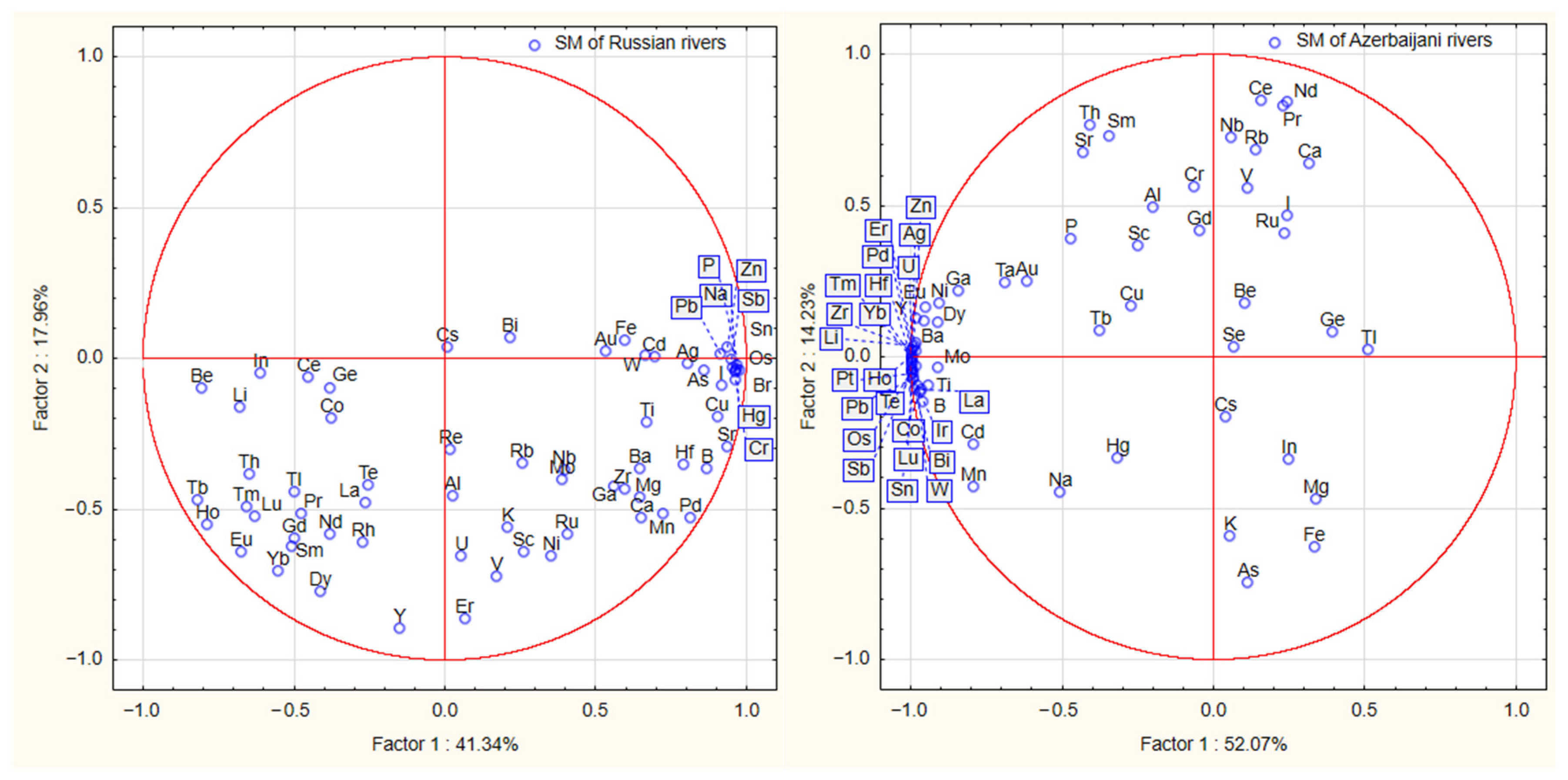

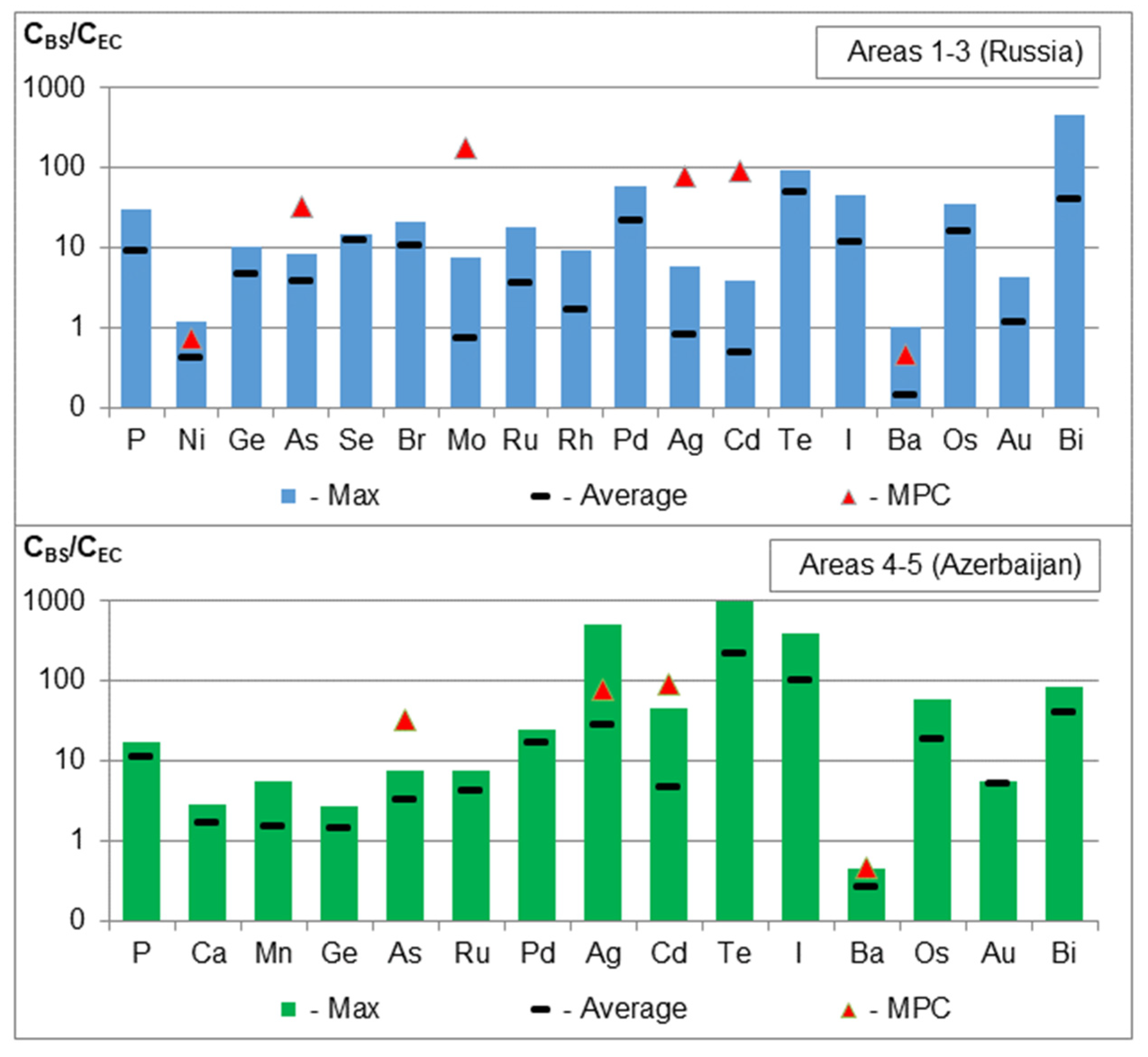

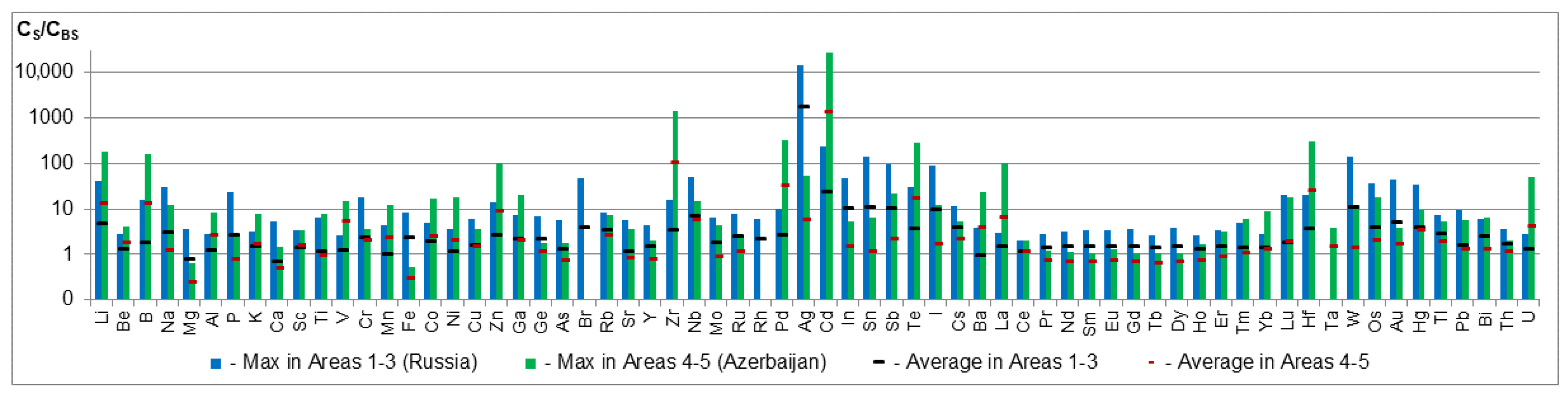

4.2. Trace Elements in Suspended Matter

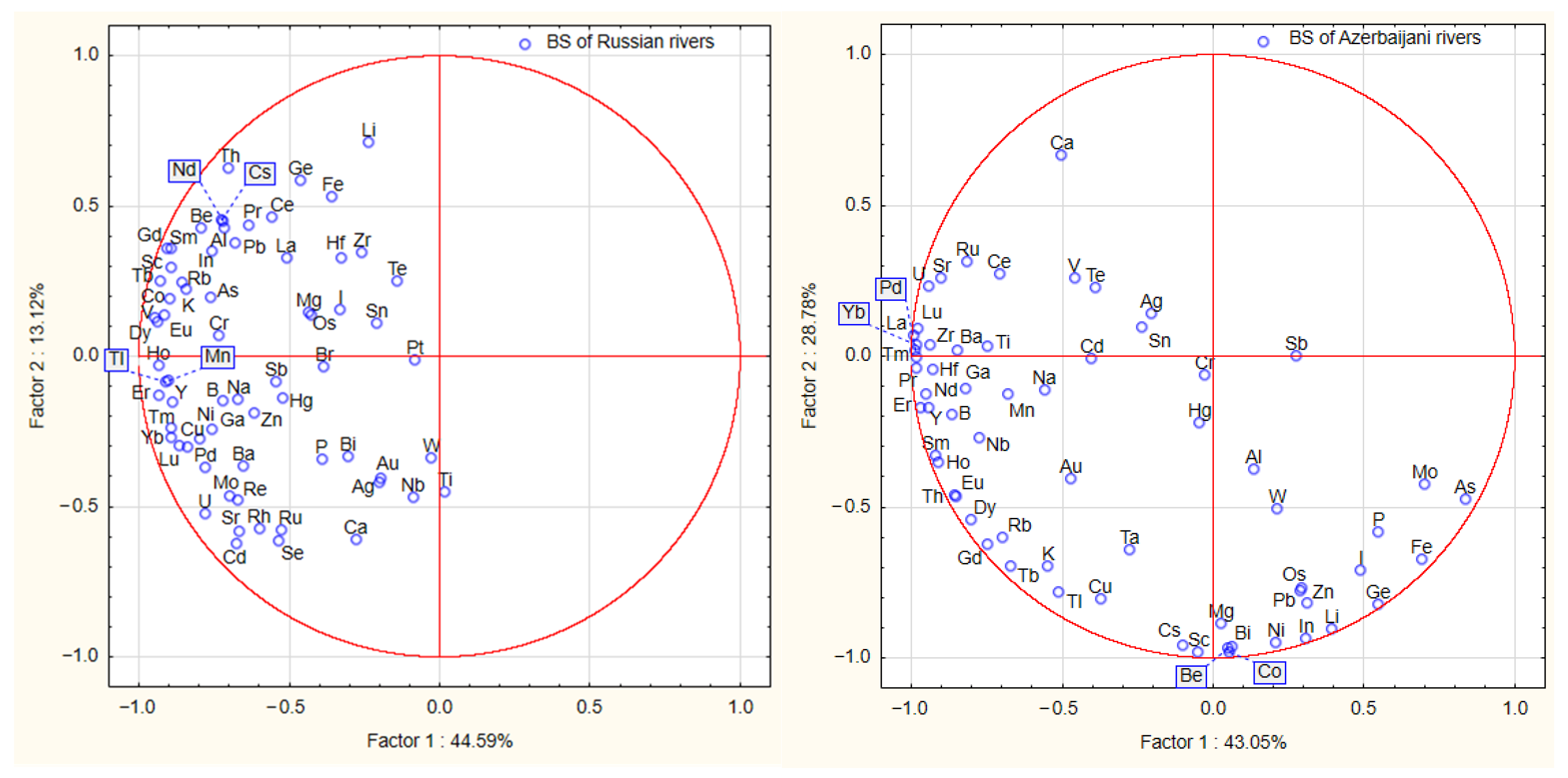

4.3. Bottom Sediments

4.4. Spatial Distribution of Elements in River Ecosystems

4.5. Rivers Sunzha, Sulak, and Ulluchay (Russia)

4.6. Karachay and Atachay Rivers (Azerbaijan)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HMs | heavy metals |

| SPM | suspended particulate matter |

| ICP-MS | inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry |

| MACs | maximum allowable concentrations, MACs |

| EF | enrichment factor |

| REEs | rare earth elements |

| TSS | total suspended solids |

| DEM | digital elevation model |

| IBSS | A. O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of RAS |

| MPCdr | maximum permissible concentrations used for drinking and recreational purposes |

| MPCfw | maximum permissible concentrations used for fishery water quality standards |

| MPCazs | maximum permissible concentrations to the national drinking water standards of Azerbaijan |

| MPCdl | maximum permissible concentrations for dissolved forms of trace elements in water |

| MPCtot | maximum permissible concentrations for total concentrations |

| MPCsed | maximum permissible concentrations for contaminants in bottom sediments |

| AC | accumulation coefficient |

| BS | bottom sediments |

| TSM | total suspended matter |

| Eh | negative redox potential |

Appendix A

| Site. No. | Date of Sampling | Water Basin | Location Coordinates | Observations of the Area | Field Observations of Water | Field Observations of Sediments/Soils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 August 2024 | Sulak River | 43.259126° N 47.537988° E | The sampling site closest to the confluence with the Caspian Sea | Turbid water; weak flow | Silt-gray—viscous—no additional features—odorless |

| 2 | 12 August 2024 | Sulak River | 43.3657051° N 47.1130054° E | Upstream section of the river with a steep (eroded) bank slope | Turbid water; moderate flow | Silt-gray—less viscous—no additional features—odorless |

| 3 | 13 August 2024 | The Andean Koisu (Sulak river basin) | 42.7838265° N 46.7084910° E | Station located downstream of the confluence of rivers and the reservoir | Highly turbid water; strong flow | Silt with fine sand admixture—gray—medium plasticity—no additional features—odorless |

| 4 | 13 August 2024 | The Andean Koisu (Sulak river basin) | 42.7470082° N 46.8311485° E | Water sampled from the discharge canal of the Irganay Hydropower Plant | Clear water; sample collected immediately downstream of the dam | Gravel (coarse and fine) with coarse sand admixture—mixed color—heterogeneous texture—no additional features—odorless |

| 5 | 13 August 2024 | Karakoysu (Sulak River basin) | 42.5511654° N 46.9678067° E | Sample collected from a silty section, as coarse gravel dominates along the banks | Turbid water; strong flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—medium plasticity—no additional features—odorless |

| 6 | 13 August 2024 | The Andean Koisu (Sulak river basin) | 42.542857° N 46.961278° E | Sample collected from a silty section | Water less turbid than at site 5; moderate flow | Silt with fine sand and coarse clastic admixture—gray—medium plasticity—surface layer covered with algal film—odorless |

| 7 | 13 August 2024 | The Andean Koisu (Sulak river basin) | 42.566422° N 46.961170° E | Sample collected from a silty section | Turbid water; weak flow | Sand, fine-grained, with silt admixture—light gray—fine texture—no additional features—odorless |

| 15 | 18 August 2024 | Sulak River | 43.265222° N 46.89490° E | Sample collected from a silty section of the Sulak River floodplain, in the area of the bank-protection dam | Clear water; weak flow Abundant fish and tadpoles observed | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—medium plasticity—abundant fine and medium gravel—odorless |

| 16 | 18 August 2024 | Chiryurt reservoir (Sulak River basin) | 43.129265° N 46.846214° E | Sample collected from a silty section | clear water; no flow | Silt-gray—liquid—odor of decomposed organic matter |

| 17 | 18 August 2024 | Chirkeyskoye reservoir (Sulak River basin) | 42.998112° N 46.896593° E | Located near a recreation facility, with runoff from the highway | Turbid water; considerable litter present | Sand, fine-grained, with admixture of silt and coarse clastic material—gray—fine texture—abundant vegetation and marl—odorless |

| 18 | 19 August 2024 | Kazikumukhskoye Koisu (Sulak River basin) | 42.501137° N 47.062029° E | Near the village of Gergebil, with vertical rocky cliffs | Turbid water; strong flow | Silt with fine-grained gray sand admixture—viscous—odorless |

| 19 | 19 August 2024 | Gatsailinsky reservoir (Sulak River basin) | 42.505932° N 46.900056° E | Sample collected from a silty section | Turbid water; weak flow | Silt-gray—viscous—odorless |

| 20 | 19 August 2024 | Avar Koisu (Sulak River basin) | 42.185360° N 46.346697° E | Confluence of the Djirmut and Khanzor rivers, forming the Avar Koisu | Turbid water; moderate flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—medium plasticity—presence of gravel—odorless |

| 8 | 14 August 2024 | The Ulluchay River | 42.2038221° N 48.0178070° E | Wide river section; settlement and fish-processing plant located nearby | Turbid water; moderate flow | Silt with sand admixture—gray—liquid—odorless |

| 9 | 14 August 2024 | The Ulluchay River | 42.0359673° N 47.7814836° E | Large boulders along the banks | Turbid water; moderate flow | Silt with sand and decomposed leaf admixture (between stones)—gray—medium plasticity—odorless |

| 10 | 15 August 2024 | The Ulluchay River | 41.971074° N 47.439094° E | Near the village of Kunki; livestock farm in the vicinity; coarse clastic material along the banks | Clear water | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—with oxidized surface layer—odorless |

| 11 | 15 August 2024 | The Ulluchay River | 41.996778° N 47.582291° E | Near the village of Itsari | Clear water; rapid flow; large boulders along the banks | Sand, fine-grained, with silt admixture and clastic material—odorless |

| 12 | 16 August 2024 | Jivus (Ulluchay River basin) | 42.104276° N 47.763029° E | 2 km upstream from the confluence with the Ulluchay River; coarse gravel along the banks; sample collected from a silty section | Turbid water; strong flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture and coarse gravel—gray—viscous—odorless |

| 13 | 16 August 2024 | The Ulluchay River | 42.286798° N 48.133469° E | Mouth of the Ulluchay River, at its confluence with the Caspian Sea | Turbid water; abundant surface litter; weak flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—viscous—with mollusk shells—odorless |

| 14 | 16 August 2024 | Bugan (Ulluchay River basin) | 42.124791° N 47.613141° E | Sample collected from a silty section, with sandstone outcrops | Turbid water; strong flow | Sand-gray—with silt admixture—odorless |

| 21 | 23 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.318015° N 45.136283° E | Republic of Ingushetia, village of Barsuki | Clear water; moderate flow; eutrophic backwater with abundant vegetation | Silt-gray to dark gray—liquid—with abundant decomposed organic matter and strong odor—numerous stones present |

| 22 | 23 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.318015° N 45.146283° E | Vicinity of the village of Sernovodsk | Clear water; moderate flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—viscous—odorless—abundant small stones |

| 23 | 23 August 2024 | The Assa River (Sunzha River basin) | 43.251638° N 45.428024° E | Vicinity of the village of Novy Sharoy | Turbid water; moderate flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—viscous—with H2S odor—coarse gravel present |

| 24 | 23 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.255000° N 45.42086111° E | Vicinity of the village of Zakan-Yurt | Turbid water; moderate flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—viscous—numerous stones and fragments of plants—odorless |

| 25 | 24 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.2524094° N 45.5121152° E | Vicinity of the village of Alkhan-Kala, near the road bridge | Turbid water; weak flow | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—with oxidized surface layer—faint odor of decomposed organic matter |

| 26 | 24 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.250392° N 45.575238° E | Vicinity of the village of Alkhan-Yurt, adjacent to riverbed widening works | Turbid water; weak flow | Silt-viscous—minor sand admixture—surface layer enriched with oxidized organic matter—faint H2S odor—silted banks |

| 27 | 26 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.440629° N 46.134110° E | Vicinity of the village of Braguny, at the confluence of the Sunzha and Terek rivers | Highly turbid water; weak flow | Silt-viscous—clayey—gray—odorless |

| 28 | 26 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.365294° N 46.065576° E | Vicinity of the village of Kundukhovo, near the town of Gudermes, at the confluence with the Belka River | Turbid water; moderate flow; plume of more turbid water from the Belka River | Silt with fine-grained sand admixture—gray—with washed material from brown clay banks |

| 29 | 26 August 2024 | Argun River (Sunzha River basin) | 43.315776° N 45.891950° E | Region of Argun | Dark turbid water; strong flow | Fine-grained gray sand with silt admixture, abundant decomposed plant matter, slight odor, pebbles present. |

| 30 | 26 August 2024 | The Sunzha River | 43.339914° N 45.755358° E | City Area of Staraia Sunzha village, suburb of Grozny city | Turbid water; weak flow | Viscous silt with fine sand admixture, abundant leaves, slight H2S odor. |

| Site No. | Date of Sampling | Water Basin | Location Coordinates | Observations of the Area | Field Observations of Water | Field Observations of Sediments/Soils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.111389° N, 48.327778° E | Sampling site located upstream of the village of Garhun. | Water turbid, odorless. | Fine gravel with silt admixture. |

| 2 | 17 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.144722° N, 48.359444° E | Sampling site located downstream of the villages of Garhun and Ryuk, before the river enters the canyon. | Water turbid, odorless; flow turbulent. | Silty-sandy, odorless, dark color, nearly black. |

| 3 | 18 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.244722° N, 48.470833° E | Area upstream of the village of Digyakh, where the river divides into several narrow channels; sampling was conducted in the widest section. | Water turbid with a high concentration of suspended matter, gray-brown in color; flow rapid. | Silty-sandy, odorless, dark color, nearly black. |

| 4 | 18 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.294722° N, 48.521944° E | In the vicinity of the village of Armaki (Ermeki), the river divides into several narrow channels; sampling was conducted in the widest channel. | Water turbid, high suspended solids, gray-brown color. Flow rapid. | Silty-sandy, odorless. Color dark, nearly black. |

| 5 | 18 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.328056° N, 48.560000° E | Near the village of Nugadi, upstream of the road bridge. | Water turbid, high suspended solids, gray-brown color. Flow rapid. | Silty-sandy, odorless. Color dark, nearly black. |

| 6 | 18 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.361389° N, 48.654444° E | Near the village of Karachay, upstream of the road bridge. | Water turbid, brown color, high suspended solids. Flow very rapid. | Odorless, compact clay with sand. |

| 7 | 18 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.378556° N, 48.755833° E | In the vicinity of the village of Garachy-Zeid, the river splits into several narrow channels; sampling was conducted in the widest channel. | Water highly turbid, high suspended solids, gray-brown color. Flow rapid. | Silty-sandy, odorless. Color dark, nearly black. |

| 13 | 20 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.461389° N, 48.975000° E | The closest point upstream of the river mouth. | Water turbid, high suspended solids. Flow moderate. | Compact clay with sand. |

| 14 | 20 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.444722° N, 48.892778° E | Sampling conducted under the bridge, downstream of the village of Karakashly; vegetation present along the banks. | Water turbid, brown color, high suspended solids. Flow moderate. | Compact clay with sand. |

| 15 | 20 October 2024 | Karachay River | 41.411389° N, 48.823056° E | Area near the village of Khulyovlyu. | Water highly turbid, dark brown, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity moderate. | Dense clay with sand. |

| 8 | 19 October 2024 | Atachay River | 41.094722° N, 49.157778° E | The river channel is located in a ravine, with saline-type soils along both banks. | Water highly turbid, brown, with a large amount of suspended solids. | Dense brown clay with sand inclusions, odorless. |

| 9 | 19 October 2024 | Atachay River | 41.078056° N, 49.143333° E | Sampling conducted near the bridge and road, upstream of the settlement of Kolani. | Water turbid, brown, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity moderate. | Dense brown clay with sand inclusions, odorless. |

| 10 | 19 October 2024 | Atachay River | 41.094722° N, 49.175833° E | Sampling in the estuarine section, before the river discharges into the sea. | Water highly turbid, brown, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity moderate. | Silt and clay, brown, with sand inclusions, H2S odor. |

| 11 | 19 October 2024 | Atachay River | 41.094722° N, 49.148333° E | An automobile highway runs nearby, with agricultural fields on both sides of the channel. | Water highly turbid, brown, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity moderate. | Clay and silt, light brown, with H2S odor. |

| 12 | 19 October 2024 | Atachay River | 41.044722° N, 49.125556° E | Under the bridge, one bank is reinforced with a concrete wall. Slightly downstream, an apparent waste dump is present, with trash being burned. | Water highly turbid, brown, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity moderate. | Water-saturated clay, light brown, with H2S odor. |

| 16 | 21 October 2024 | Atachay River | 40.961389° N, 49.029444° E | The river enters a deep canyon. Slightly upstream, a large tributary flows into the river. | Water is highly turbid, dark brown in color, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity is fast. | Dense clay with minor sand admixture, no odor. |

| 17 | 21 October 2024 | Atachay River | 40.928056° N, 49.036667° E | Sampling conducted upstream of the confluence with the large tributary. | Water is highly turbid, dark brown in color, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity is fast. | Soft soil with silty texture, two cores (58 mm diameter) collected from the 0–5 cm surface layer, no odor. |

| 18 | 21 October 2024 | Atachay River | 40.911389° N, 48.979444° E | Sampling in the settlement of Bakshishly; vehicles cross the river at this point, and livestock graze along the banks. | Water is highly turbid, dark brown in color, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity is fast. | Soft silty soil with characteristic silty odor. |

| 19 | 21 October 2024 | Atachay River | 40.878056° N, 48.934167° E | Sampling downstream of the settlement of Altyagach. The riverbanks are heavily littered. | Water is highly turbid, dark brown in color, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity is fast. | Soft silty soil with characteristic silty odor. |

| 20 | 21 October 2024 | Atachay River | 40.861389° N, 48.906389° E | Sampling upstream of the settlement of Altyagach. | Water is highly turbid, dark brown in color, with a large amount of suspended solids. Flow velocity is fast. | Dense clay with minor sand admixture, no odor. |

References

- Jiang, X.; Kirsten, K.L.; Qadeer, A. Contaminants in the Water Environment: Significance from the Perspective of the Global Environment and Health. Water 2025, 17, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, M.; Moradkhani, H.; Ahmadalipour, A.; Moftakhari, H.; Abbaszadeh, P.; Alipour, A. A Review of the 21st Century Challenges in the Food-Energy-Water Security in the Middle East. Water 2019, 11, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, A.; Azhaari, R.N.N.; Hu, A.H.; Kuo, C.-H.; Huang, H. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment Study on Carbon Footprint of Water Treatment Plants: Case Study of Indonesia and Taiwan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More than 2 Billion People Lack Access to Safe Drinking Water. Available online: https://www.ungeneva.org/ru/news-media/news/2025/06/107871/bolee-2-milliardov-chelovek-ne-imeyut-dostupa-k-bezopasnoy-pitevoy (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Four billion people facing severe water scarcity. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.d.C.; Mohamed, A.A.; Feitosa, P. Sustainable development goal 6 monitoring through statistical machine learning–Random Forest method. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2024, 8, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehu, B.; Nazim, F. Clean Water and Sanitation for All: Study on SDGs 6.1 and 6.2 Targets with State Policies and Interventions in Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yu, X.; Xu, B.; Wang, Q.; Wei, X.; Wang, B.; Zhao, X.; Gao, F. Interactions Between SDG 6 and Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study from Chenzhou City, China’s Sustainable Development Agenda Innovation Demonstration Area. Land 2025, 14, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassardo, C.; Jones, J.A.A. Managing Water in a Changing World. Water 2011, 3, 618–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, Y.; Infante, D.M. Disentangling Effects of Natural Factors and Human Disturbances on Aquatic Systems—Needs and Approaches. Water 2023, 15, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisetskii, F. Rivers in the Focus of Natural-Anthropogenic Situations at Catchments. Geosciences 2021, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Singh, N.; Rai, S.N.; Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, M.P.; Sahoo, A.; Shekhar, S.; Vamanu, E.; Mishra, V. Heavy Metal Contamination in the Aquatic Ecosystem: Toxicity and Its Remediation Using Eco-Friendly Approaches. Toxics 2023, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Estévez, M.; López-Periago, E.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Mejuto, J.-C.; García-Río, L. The mobility and degradation of pesticides in soils and the pollution of groundwater resources. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 123, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamid, H.F.; Abd-Elmoneem, S.M.; Abdelaal, G.M.; Zeleňáková, M.; Vranayova, Z.; Abd-Elaty, I. Investigating and Managing the Impact of Using Untreated Wastewater for Irrigation on the Groundwater Quality in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Liang, M.-C.; Laskar, A.H.; Huang, K.-F.; Maurya, N.S.; Singh, V.; Ranjan, R.; Maurya, A.S. Basin-Scale Geochemical Assessment of Water Quality in the Ganges River during the Dry Season. Water 2023, 15, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Tamminga, K.R. The Ganges and the GAP: An Assessment of Efforts to Clean a Sacred River. Sustainability 2012, 4, 1647–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juwana, I.; Sodri, A.; Muttil, N.; Hikmat, R.R.; Indira, A.L.; Sutadian, A.D. Potential Pollution Loads of the Cikembar Sub-Watershed to the Cicatih River, West Java, Indonesia. Water 2024, 16, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sor, R.; Ngor, P.B.; Soum, S.; Chandra, S.; Hogan, Z.S.; Null, S.E. Water Quality Degradation in the Lower Mekong Basin. Water 2021, 13, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xin, C.; Yu, S. A Review of Heavy Metal Migration and Its Influencing Factors in Karst Groundwater, Northern and Southern China. Water 2023, 15, 3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokar’, E.; Kuzmenkova, N.; Rozhkova, A.; Egorin, A.; Shlyk, D.; Shi, K.; Hou, X.; Kalmykov, S. Migration Features and Regularities of Heavy Metals Transformation in Fresh and Marine Ecosystems (Peter the Great Bay and Lake Khanka). Water 2023, 15, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.N.; Lebedev, Y.; Drygval, A.; Gorbunov, R.; Gorbunova, T.; Kuznetsov, A.; Kuznetsova, S.; Nguyen, D.H.; Tabunshchik, V. Content of heavy metals in soils of Bidoup Nui Ba National Park (Southern Vietnam). J. Degraded Min. Lands Manag. 2024, 11, 6413–6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, M. How Have Emissions and Weather Patterns Contributed to Air Pollution in Lanzhou, China? Atmosphere 2025, 16, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabunshchik, V.; Nikiforova, A.; Lineva, N.; Drygval, P.; Gorbunov, R.; Gorbunova, T.; Kerimov, I.; Pham, C.N.; Bratanov, N.; Kiseleva, M. The Dynamics of Air Pollution in the Southwestern Part of the Caspian Sea Basin (Based on the Analysis of Sentinel-5 Satellite Data Utilizing the Google Earth Engine Cloud-Computing Platform). Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabunschik, V.; Gorbunov, R.; Bratanov, N.; Gorbunova, T.; Mirzoeva, N.; Voytsekhovskaya, V. Fatala River Basin (Republic of Guinea, Africa): Analysis of Current State, Air Pollution, and Anthropogenic Impact Using Geoinformatics Methods and Remote Sensing Data. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadova, L.; Negri, S.; Tahmazova, M.-K.; Mammadov, V. A Hydrological and Hydrochemical Study of the Gudiyalchay River: Understanding Groundwater–River Interactions. Water 2024, 16, 2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhalov, R.M.; Zurkhaeva, U.D.; Lobachev, E.N.; Shikhshabekova, B.I. To the Question of the Fishery Suitability of the Mountain Rivers of Dagestan on the Example of the River Sana (a Tributary of the Kazikumukhskoye Koysu River). Daghestan GAU Proc. 2023, 2, 90–95. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Magomedov, A.M.; Omarova, P.A.; Garunov, O.M.; Gadzhieva, M.A.; Gasbanova, Z.I. The Impact of Changes in the Regime of Dagestan’s Rivers on the Biodiversity of Coastal Ecosystems. Mod. Sci. Actual Probl. Theory practice. Ser. Nat. Tech. Sci. 2025, 4, 14–17. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samedov, S.G.; Ibragimova, T.I. Assessment of the Samur River Basin Water Recourses Quality. Water Sect. Russ. Probl. Technol. Manag. 2014, 14, 4–16. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, L.V.; Maslova, O.V.; Belkina, A.V.; Sukhareva, K.V. Global Climate Changing and its after-Effects. Vestn. Plekhanov Russ. Univ. Econ. 2018, 2, 84–93. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov-Danilyan, V.I. Global climate problem and forecasting possibilities. Century Glob. 2019, 4, 3–15. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilaș, S.; Burescu, F.-L.; Chereji, B.-D.; Munteanu, F.-D. The Impact of Anthropogenic Activities on the Catchment’s Water Quality Parameters. Water 2025, 17, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabunshchik, V.; Nikiforova, A.; Lineva, N.; Gorbunov, R.; Gorbunova, T.; Kerimov, I.; Nasiri, A.; Pham, C.N. Uncovering Anthropogenic Changes in Small- and Medium-Sized River Basins of the Southwestern Caspian Sea Watershed: Global Information System and Remote Sensing Analysis Using Satellite Imagery and Geodatabases. Water 2025, 17, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protasov, V.F.; Molchanov, A.V. Ecology, Health and Nature Management in Russia; Finance and Statistics: Moscow, Russia, 1995; 524p. [Google Scholar]

- Denisov, V.I.; Latun, V.V. Flows of Chemical Elements in Suspended Matter Fluxes in the Shallow Area of the Black Sea Shelf (according to the Sediment Traps Data). Izv. Vuzov. Sev.-Kavk. Region. Nat. Sci. 2018, 4, 77–85. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egorov, V.N. Theory of Radioisotope and Chemical Homeostasis of Marine Ecosystems; A. O. Kovalevsky Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of RAS: Sevastopol, Russia, 2019; 356p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Linnik, P.M.; Zubenko, I.B. Role of bottom sediments in the secondary pollution of aquatic environments by heavy-metal compounds. Lakes Reserv. Sci. Policy Manag. Sustain. Use 2000, 5, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urazmetov, I.A.; Gubeeva, S.K.; Ulengov, R.A. Hydrology of Rivers; Kazan Federal University: Kazan, Russia, 2024; 139p. [Google Scholar]

- Gulin, S.B.; Egorov, V.N.; Stokozov, N.A.; Mirzoeva, N.Y. Determination of the age of bottom sediments and assessment of the sedimentation rate in coastal and deep-water areas of the Black Sea using natural and anthropogenic radionuclides. In Radioecological Response of the Black Sea to the Chernobyl Accident; Polikarpov, G.G., Egorov, V.N., Eds.; ECOSI-Gidrophysics: Sevastopol, Ukraine, 2008; pp. 499–503. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tereshchenko, N.N.; Gulin, S.B.; Proskurnin, V.Y.; Paraskiv, A.A. Geochronological Reconstruction of Sedimentary Flows of Technogenic Plutonium Based on Radioisotope Determination of the Rate of Sedimentation of Suspended Matter in Sediments on a Half-Century Scale. In The Black Sea System; Lisitzin, A.P., Ed.; Scientific World: Moscow, Russia, 2018; pp. 641–659. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunya, A.N.; Kerimov, I.A.; Gayrabekov, U.T.; Nikiforova, A.A. Landscape-Geoecological Framework Of The Sunzha River Basin. Sustain. Dev. Mt. Territ. 2024, 16, 1450–1459. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabunshchik, V.; Dzhambetova, P.; Gorbunov, R.; Gorbunova, T.; Nikiforova, A.; Drygval, P.; Kerimov, I.; Kiseleva, M. Delineation and Morphometric Characterization of Small- and Medium-Sized Caspian Sea Basin River Catchments Using Remote Sensing and GISs. Water 2025, 17, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorov, A.M. (Ed.) Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd ed.; In 30 Volumes; 1969–1978; Soviet Encyclopedia: Moscow, Russia, 1981; Available online: https://archive.org/details/B-001-033-601-30vols/BSE_3izd_01/ (accessed on 20 August 2025). (In Russian)

- Sunzha River/verum.icu//State Water Register/Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia. 2021. Available online: https://verum.icu/wiki/Сунжа_(притoк_Терека) (accessed on 20 August 2025). (In Russian).

- Nazirova, K.; Lavrova, O.; Alferyeva, Y.; Knyazev, N. Spatiotemporal plume variability of Terek and Sulak rivers from satellite data and concurrent in situ measurements. Curr. Probl. Remote. Sens. Earth Space 2023, 20, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtova, P.P. (Ed.) Surface Water Resources of the USSR: Hydrological Study; Transcaucasia and Dagestan. Issue 3. Dagestan; Gidrometeoizdat: Leningrad, USSR, 1964; Volume 9, 76p. [Google Scholar]

- Dictionary of Names of Hydrographic Objects of Russia and Other CIS Member Countries; Donidze, G.I., Ed.; Kartgeocenter–Geodezizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1999; 351p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Sulak/textual.ru//State Water Register: [Archive. 15 October 2013]/Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia. 2009. Available online: https://verum.icu/wiki/Сулак_(река) (accessed on 20 August 2025). (In Russian).

- Shakhbanova, A.M.; Nabiev, O.S. Natural conditions of the Ulluchay River basin. In Science and Education State, Problems, Development Prospects, Proceedings of the Scientific Session of the Teaching Staff, Dedicated to the 90th Anniversary of the Scientist, Teacher, Organizer of Education Akhmed Magomedovich Magomedov, Makhachkala, Russia, 29–30 October 2020; Dagestan State Pedagogical University: Makhachkala, Russia, 2021; pp. 712–715. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Balguev, T.R. Geomorphological features of the Ulluchay River valley in the Eastern Caucasus. Nat. Tech. Sci. 2008, 6, 197–201. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Ulluchay/verum.icu//State Water Register/Ministry of Natural Resources of Russia. 2021. Available online: https://verum.icu/wiki/Уллучай (accessed on 20 August 2025). (In Russian).

- Shabanov, J.A.; Kholina, T.A. Soil and Landscape Changes in the Alpine Zone Basin of the Rivers Garachay-Velvelechay. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2016, 5, 1039–1048. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrisov, I.A.; Guseynova, A.S.h. Landslide propagation in the Atachay River basin. In Geoecological Assessment of Mountain River Basins: Theoretical, Methodological and Methodological Aspects, Regional Studies, Proceedings of the II International Scientific Conference, Grozny, Russia, 25 December 2024; Millionshchikov Grozny State Oil Technological University: Grozny, Russia, 2025; pp. 59–60. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Azerbaijan Soviet Encyclopedia; National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan: Baku, Azerbaijan, 1976; p. 459. (In Azerbaijani)

- Atayev, Z.V.; Kuchinskaya, I.Y.; Kerimova, E.D. Landscape structure of the Garachay and Atachay river basins in the South-Eastern Caucasus. In Geoecological Assessment of Mountain River Basins: Theoretical-Methodological and Methodological Aspects, Regional Studies, Proceedings of the II International Scientific Conference, Grozny, Russia, 25 December 2024; Millionshchikov Grozny State Oil Technological University: Grozny, Russia, 2025; pp. 28–35. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kashirina, E.; Gorbunov, R.; Kerimov, I.; Gorbunova, T.; Drygval, P.; Chuprina, E.; Nikiforova, A.; Lineva, N.; Drygval, A.; Kelip, A.; et al. Spatial Distribution of Geochemical Anomalies in Soils of River Basins of the Northeastern Caucasus. Geosciences 2025, 15, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 17.1.5.01-80; Environmental Protection. Hydrosphere. General Requirements for Sampling Bottom Sediments of Water Bodies for Pollution Analysis. Publishing House of Standards: Moscow, Russia, 2002; 7p. (In Russian)

- RD 52.10.243-92; Guide to Chemical Analysis of Sea Water. Gidrometeoizdat: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1993; 264p. (In Russian)

- PNDF 14.1:2:3.110-97; Quantitative Chemical Analysis of Water. Methodology for Measuring the Mass Concentration of Suspended Solids in Samples of Natural and Waste Water Using the Gravimetric Method. FSBI Federal Center for Analysis and Evaluation of Technogenic Impact: Moscow, Russia, 2016; 15p. Available online: http://gost.gtsever.ru/Index2/1/4293751/4293751544.htm (accessed on 23 November 2025). (In Russian)

- PNDF 16.2.2:2.3.71-2011; Methodology for Measuring the Mass Fractions of Metals in Sewage Sludge, Bottom Sediments, and Plant Samples Using Spectral Methods. Federal Service for Supervision of Natural Resources: Moscow, Russia, 2011; 45p. (In Russian)

- GOSTR 56219-2014; Determination of the Content of 62 Elements by Mass Spectrometry with Inductively Coupled Plasma. Standartinform: Moscow, Russia, 2015; 36p. (In Russian)

- EPA 200.7:2001; Trace Elements in Water, Solids, and Biosolids by Inductively Coupled Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectrometry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, WA, USA, 2001; 68p. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-08/documents/method_200-7_rev_5_2001.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- SanPiN 1.2.3685-21; Hygienic Standards and Requirements for Ensuring the Safety and (or) Harmlessness of Environmental Factors for Humans. Regional Cadastral Center: Orenburg, Russia, 2021. Available online: https://gor-lab.ru/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/SanPiN_123685_21.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025). (In Russian)

- AZS 929:2023; Drinking Water. Hygienic Requirements and Quality Control. Azerbaijan Standardization Institute: Baku City, Azerbaijan, 2023. Available online: https://sdnx.gov.az/assets/front/img/page/1750237367949462743.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025). (In Azerbaijani)

- Vinogradov, A.P. Average content of chemical elements in the main types of igneous rocks of the earth’s crust. Geochemistry 1962, 7, 555–571. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Warmer, H.; van Dokkum, R. Water Pollution Control in the Netherlands; Policy and Practice 2001, 77, RIZA Report 2002.009; 2002; 76p, Available online: https://open.rijkswaterstaat.nl/@118574/water-pollution-control-the-netherlands/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Barbieri, M. The Importance of Enrichment Factor (EF) and Geoaccumulation Index (Igeo) to Evaluate the Soil Contamination. J. Geol. Geophys. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starodymova, D.P.; Shevchenko, V.P.; Kokryatskaya, N.M.; Aliev, R.A. Dynamics of heavy metals accumulation by bottom sediments of the water body in the TPP impact area. Hydrosphere Ecol. 2023, 2, 72–83. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanPiN 2.1.4.1074-01; Drinking Water. Hygienic Requirements for the Quality of Water in Centralized Drinking Water Supply Systems. Quality Control (Replacing SanPiN 2.1.4.559-96). Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia, 2001. (In Russian)

- Martin, J.M.; Meybeck, M. Elemental mass balance of materiel carried by worldmajor rivers. Mar. Chem. 1979, 7, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillardet, J.; Viers, J.; Dupre, B. Trace elements in river waters. In Treatise on Geochemistry; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 195–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvartsev, S.L. Hydrogeochemistry of the Hypergenesis Zone; Publishing house “Nedra”: Moscow, Russia, 1998; 366p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Savenko, V.S. Chemical Composition of Suspended Sediments of the World’s Rivers; GEOS: Moscow, Russia, 2006; 174p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Viers, J.; Dupre, B.; Gaillarde, J. Chemical Composition of Suspended Sediments in World Rivers: New Insight from a New Database. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, V.V. Ecological Geochemistry of Elements: In 6 Books/Committee of the Russian Federation on Geology and Use of Subsoil; Nedra: Moscow, Russia, 1997. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.R. Abundance of chemical elements in the continental crust: A new table. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1964, 28, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.D.; Carr, R.S.; Calder, F.D.; Long, E.R.; Ingersoll, C.G. Development and evaluation of sediment quality guidelines for Florida coastal waters. Ecotoxicology 1996, 5, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Figueroa, D.; Jimenez, B.D.; Rodriguez-Sierra, C.J. Trace metals in sediments of two estuarine lagoons from Puerto Rico. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 141, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losev, O.V. Heavy metals and petroleum hydrocarbons contents in bottom sediments of Uglovoy Bay (Peter the Great Bay, Sea of Japan). Vestn. Far East Branch Russ. Acad. Sci. 2020, 5, 104–115. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geology of the USSR; Vol. XL-HI Azerbaijan SSR. Useful minerals; Nedra: Moscow, Russia, 1976; pp. 377–378. (In Russian)

- Abdulaev, S.-S.O.; Dokholyan, S.V.; Cherkashin, V.I. Mineral resources and their effect on the social and economic development in the Republic of Dagestan. Gorn. Zhurnal. 2016, 4, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusupov, A.R.; Mamaev, S.A.; Yusupov, Z.A.; Mamaev, A.S. Study of zeolite-containing silicon rocks of Dagestan for obtaining a mineral additive to cement. Vestn. Geosci. 2021, 10, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbanov, M.M.; Dashtiev, Z.K. Geological and economic zoning of the mineral resource base of the Republic of Dagestan. Proc. Inst. Geol. Dagestan Sci. Cent. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2012, 58, 35–45. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kurbanov, M.M.; Dashtiev, Z.K.; Belyaev, E.M. Mineral resource base of solid minerals and hydrocarbon raw materials of the Republic of Dagestan. Proc. Inst. Geol. Dagestan Sci. Cent. Russ. Acad. Sci. 2011, 57, 132–134. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kerimov, I.A.; Vismuradov, A.V.; Daukaev, A.A.; Dolya, A.N.; Rudov, V.A.; Murdalov, L.A. Solid Non-Metallic Mineral Resources of the Chechen Republic: Exploration Condition and Recommendations on Their Exploitation. Geol. Geophys. Russ. South 2015, 2, 28–41. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daukaev, A.A.; Zaburaeva, H.S.; Gatsaeva, L.S.; Daukaev, A.A.; Sarkisyan, I.V.; Gatsaeva, S.S. Natural mineral waters of the Chechen Republic: Current usage and prospects for development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 579, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendieva, Z.J. Metallic minerals of Azerbaijan. Gorn. Zhurnal. 2019, 1, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efendieva, Z.J. Non-metallic resources of Azerbaijan. Gorn. Zhurnal. 2018, 3, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkashin, V.I.; Gazaliev, I.M. Rospects of Development of Ore Deposits Dagestan (Environmental Aspects). Geol. Geophys. Russ. South 2016, 1, 132–140. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shestakov, B.I. On the methodology for quantitative assessment of the effect of Eh and pH on the content of trace elements in natural waters. Izv. Tomsk. Politekh. Instituta 1977, 238, 63–66. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- GNC FGUGP Yuzhmorgeologia; FGUGP Kavkazgeols’emka. Geological Map K 37 (Sochi); K 38 (Makhachkala); K 39. In State Geological Map of the Russian Federation, 3rd ed.; Prutskii, N.I., Yubko, V.M., Eds.; Scythian Series; Geological Library: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2009; Available online: https://www.geokniga.org/maps/7028 (accessed on 20 April 2025). (In Russian)

- Gusarov, A.V.; Sharifullin, A.G.; Komissarov, M.A. Contemporary Long-Term Trends in Water Discharge, Suspended Sediment Load, and Erosion Intensity in River Basins of the North Caucasus Region, SW Russia. Hydrology 2021, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudryn, A.; Gibert-Brunet, E.; Tucholka, P.; Antipov, M.P.; Leroy, S.A. Chronology of the Late Pleistocene Caspian Sea hydrologic changes: A review of dates and proposed climate-induced driving mechanisms. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2022, 293, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppelbaum, L.; Katz, Y.; Kadirov, F.; Guliyev, I.; Ben-Avraham, Z. Geodynamic, Tectonophysical, and Structural Comparison of the South Caspian and Levant Basins: A Review. Geosciences 2025, 15, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, N.; Reykhard, L.; Dara, O. Authigenic Minerals of the Derbent and South Caspian Basins (Caspian Sea): Features of Forms, Distribution and Genesis under Conditions of Hydrogen Sulfide Contamination. Minerals 2022, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholodov, V.N.; Nedumov, R.I. Zone of Catagenetic Hydromicatization of Clays—An Area of Intense Redistribution of Chemical Elements: Communication 2. Mineralogical–Geochemical Peculiarities of the Zone of Catagenetic Illitization. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 2001, 36, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Li | Be | B | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | K | Ca | Ti |

| MPCdr, µg·L−1 | 30 | 0.2 | 500 | 200,000 | 50,000 | 200 | 25,000 | 0.1 | – | – | 100 |

| MPCfw, µg·L−1 | 80 | 0.3 | 100 | 120,000 | 40,000 | 40 | – | 0.01 | 50,000 | 180,000 | 60 |

| MPCAZS, µg·L−1 | 2000 | 12 | 2400 | 200,000 | – | 200 | 10,000 | 0.1 | 12,000 | – | 20 |

| MPCdl, µg·L−1 | – | 0.2 | 650 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| MPCtot, µg·L−1 | – | 0.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| MPCsed, mg·kg−1 | – | 1.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Element | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | As | Se |

| MPCdr, µg·L−1 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 300 | 100 | 20 | 1000 | 5000 | – | 10 | 10 |

| MPCfw, µg·L−1 | 1 | 70 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 10 | – | 50 | 2 |

| MPCAZS, µg·L−1 | 100 | 50 | 500 | 300 | 100 | 70 | 1000 | 5000 | 5 | 10 | 40 |

| MPCdl, µg·L−1 | 4.3 | 8.7 | – | – | 2.8 | 5.1 | 1.5 | 9.4 | – | 25 | 5.3 |

| MPCtot, µg·L−1 | 5.1 | 84 | – | – | 3.1 | 6.3 | 3.8 | 40 | – | 32 | 5.4 |

| MPCsed, mg·kg−1 | 56 | 380 | – | – | 19 | 44 | 73 | 620 | – | 55 | 2.9 |

| Element | Br | Rb | Sr | Zr | Nb | Mo | Ag | Cd | Sn | Sb | Te |

| MPCdr, µg·L−1 | 200 | – | 7000 | – | 10 | 70 | 50 | 1 | 2000 | 5 | 10 |

| MPCfw, µg·L−1 | – | 100 | 400 | 70 | – | 1 | – | 5 | 112 | – | 3 |

| MPCAZS, µg·L−1 | – | 100 | 7000 | – | 10 | 250 | 50 | 1 | 5 | 20 | 10 |

| MPCdl, µg·L−1 | – | – | – | – | – | 290 | 0.08 | 0.4 | 18 | 6.5 | – |

| MPCtot, µg·L−1 | – | – | – | – | – | 300 | – | 2 | 220 | 7.2 | – |

| MPCsed, mg·kg−1 | – | – | – | – | – | 200 | 5.5 | 12 | – | 15 | – |

| Element | I | Cs | Ba | Sm | Eu | W | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | U |

| MPCdr, µg·L−1 | 125 | – | 700 | – | – | 50 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 10 | 100 | 15 |

| MPCfw, µg·L−1 | 400 | 1000 | 740 | – | – | 0.8 | 0.01 | – | 6 | – | – |

| MPCAZS, µg·L−1 | 125 | – | 1300 | 24 | 300 | 50 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 10 | 100 | 30 |

| MPCdl, µg·L−1 | – | – | 220 | – | – | – | 0.2 | 1.6 | 11 | – | 1 |

| MPCtot, µg·L−1 | – | – | 230 | – | – | – | 1.2 | 1.7 | 220 | – | – |

| MPCsed, mg·kg−1 | – | – | 300 | – | – | – | 10 | 2.6 | 530 | – | – |

| Site. No. | Date of Sampling | Coordinates | t Water (°C) | pH Water | pH Bottom Sediments | Eh Bottom Sediments (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulak River with tributaries and reservoirs (Russian Federation) | ||||||

| 1 | 12 August 2024 | 43.259126° N, 47.537988° E | 28 | 8.52 | 7.33 | −154 |

| 2 | 12 August 2024 | 43.3657051° N, 47.1130054° E | 23 | 7.83 | 6.93 | −126 |

| 3 | 13 August 2024 | 42.7838265° N, 46.7084910° E | 17 | 7.63 | 7.8 | +192 |

| 4 | 13 August 2024 | 42.7470082° N, 46.8311485° E | 17 | 7.54 | Not defined | Not defined |

| 5 | 13 August 2024 | 42.5511654° N, 46.9678067° E | 20 | 8.13 | 8.03 | 325 |

| 6 | 13 August 2024 | 42.542857° N, 46.961278° E | 20 | 7.83 | 7.62 | +138 |

| 7 | 13 August 2024 | 42.566422° N, 46.961170° E | 20 | 8.1 | 8.14 | +143 |

| 15 | 18 August 2024 | 43.265222° N, 46.894010° E | 23 | 8.49 | 8.05 | +180 |

| 16 | 18 August 2024 | 43.129265° N, 46.846214° E | 19 | 7.68 | 6.81 | −206 |

| 17 | 18 August 2024 | 42.998112° N, 46.896593° E | 25 | 8.83 | 7.77 | +148 |

| 18 | 19 August 2024 | 42.501137° N, 47.062029° E | 19 | 7.12 | 6.64 | +134 |

| 19 | 19 August 2024 | 42.505932° N, 46.900056° E | 24 | 7.56 | 6.65 | +186 |

| 20 | 19 August 2024 | 42.185360° N, 46.346697° E | 16 | 7.37 | 7.23 | +158 |

| Ulluchay River with tributaries and reservoirs (Russian Federation) | ||||||

| 8 | 14 August 2024 | 42.2038221° N, 48.0178070° E | 27 | 8.14 | 7.69 | +110 |

| 9 | 14 August 2024 | 42.0359673° N, 47.7814836° E | 17 | 8.61 | 7.81 | +168 |

| 10 | 15 August 2024 | 41.971074° N, 47.439094° E | 16 | 8.4 | 8.14 | +118 |

| 11 | 15 August 2024 | 41.996778° N, 47.582291° E | 16 | 8.41 | 7.85 | +185 |

| 12 | 16 August 2024 | 42.104276° N, 47.763029° E | 18 | 7.72 | 7.67 | +166 |

| 13 | 16 August 2024 | 42.286798° N, 48.133469° E | 25 | 7.67 | 7.43 | +151 |

| 14 | 16 August 2024 | 42.124791° N, 47.613141° E | 16 | 8.05 | 7.84 | +199 |

| Sunzha River with tributaries and reservoirs (Russian Federation) | ||||||

| 21 | 23 August 2024 | 43.318015° N, 45.136283° E | 20 | 7.05 | 6.65 | −40 |

| 22 | 23 August 2024 | 43.318015° N, 45.146283° E | 24 | 7.67 | 7.16 | −179 |

| 23 | 23 August 2024 | 43.251638° N, 45.428024° E | 21 | 7.32 | 6.9 | +49 |

| 24 | 23 August 2024 | 43.255000° N, 45.4208611° E | 22 | 7.42 | 6.65 | −37 |

| 25 | 24 August 2024 | 43.2524094° N, 45.5121152° E | 21 | 7.59 | 6.88 | −161 |

| 26 | 24 August 2024 | 43.250392° N, 45.575238° E | 23 | 7.4 | 6.71 | −182 |

| 27 | 26 August 2024 | 43.440629° N, 46.134110° E | 24 | 7.33 | 7.12 | +135 |

| 28 | 26 August 2024 | 43.365294° N, 46.065576° E | 21 | 7.44 | 7.44 | +94 |

| 29 | 26 August 2024 | 43.315776° N, 45.891950° E | 19 | 7.38 | 7.04 | −80 |

| 30 | 26 August 2024 | 43.339914° N, 45.755358° E | 21 | 7.72 | 7.12 | +70 |

| Karachay River with tributaries and reservoirs (Azerbaijan) | ||||||

| 1 | 17 October 2024 | 41.111389° N, 48.327778° E | 10 | 8.5 | 6.0 | +190 |

| 2 | 17 October 2024 | 41.144722° N, 48.359444° E | 12 | 8.6 | 6.5 | +290 |

| 3 | 18 October 2024 | 41.244722° N, 48.470833° E | 11 | 8.15 | 7.46 | +294 |

| 4 | 18 October 2024 | 41.294722° N, 48.521944° E | 11 | 9.3 | 9.46 | +286 |

| 5 | 18 October 2024 | 41.328056° N, 48.560000° E | 11 | 8.98 | 8.25 | +259 |

| 6 | 18 October 2024 | 41.361389° N, 48.654444° E | 13 | 7.62 | 7.84 | +283 |

| 7 | 18 October 2024 | 41.378556° N, 48.755833° E | 12.7 | 7.04 | 6.08 | +106 |

| 13 | 20 October 2024 | 41.461389° N, 48.975000° E | 11.7 | 8.33 | 8.45 | −64.1 |

| 14 | 20 October 2024 | 41.444722° N, 48.892778° E | 10.9 | 9.29 | 9.86 | +173 |

| 15 | 20 October 2024 | 41.411389° N, 48.823056° E | 11.5 | 9.88 | 9.52 | +152 |

| Atachay River with tributaries and reservoirs (Azerbaijan) | ||||||

| 8 | 19 October 2024 | 41.094722° N, 49.157778° E | 13.3 | 9.88 | 9.52 | +152 |

| 9 | 19 October 2024 | 41.078056° N, 49.143333° E | 13.5 | 8.79 | 9.01 | +274 |

| 10 | 19 October 2024 | 41.094722° N, 49.175833° E | 12 | 9.24 | 8.2 | +206 |

| 11 | 19 October 2024 | 41.094722° N, 49.148333° E | 13.6 | 9.3 | 8.3 | +498 |

| 12 | 19 October 2024 | 41.044722° N, 49.125556° E | 12.7 | 8.8 | 8.5 | +184 |

| 16 | 21 October 2024 | 40.961389° N, 49.029444° E | 9.8 | 9.0 | 8.3 | +82 |

| 17 | 21 October 2024 | 40.928056° N, 49.036667° E | 10 | 8.9 | 8.7 | +72 |

| 18 | 21 October 2024 | 40.911389° N, 48.979444° E | 7.5 | 8.9 | 8.9 | −158 |

| 19 | 21 October 2024 | 40.878056° N, 48.934167° E | 6.9 | 8.4 | 8.1 | +63 |

| 20 | 21 October 2024 | 40.861389° N, 48.906389° E | 4.6 | 9.5 | 9.1 | +159 |

| Element | Water | Suspended Matter | Bottom Sediments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration Range in Districts 1–3 (Russia), µg·L−1 | Concentration Range in Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan), µg·L1 | Average Concentration in the Rivers of the World, µg·L−1 | Concentration Range in Districts 1–3 (Russia), mg·kg−1 | Concentration Range in Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan), mg·kg−1 | The Average Concentration In The Rivers Of The World, mg·kg−1 | Concentration Range in Districts 1–3 (Russia), mg·kg−1 | Concentration Range in Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan), mg·kg−1 | Clark in the Earth’s Crust, mg·kg−1 | |

| Major elements | |||||||||

| Na | 3581–78,000 16,208.5 ± 2629.4 | 5500–198,000 61,725.0 ± 14,192.8 | 5100 | 104–4133 674.6 ± 173.4 | 73–7403 712.0 ± 356.7 | 7100 | 134–591 280.1 ± 18.4 | 198–1964 644.1 ± 81.8 | 25,000 |

| Mg | 39–245 101.7 ± 7.4 | – | 3800 | 1317–4488 2538.8 ± 141.3 | <200–2749 1286.0 ± 213.0 | 12,600 | 1104–5855 3781.9 ± 184.3 | 2376–10,068 5102.3 ± 491.3 | 18,700 |

| Al | 12.8–26.8 16.5 ± 0.6 | 2.8–28.0 8.5 ± 1.4 | 32 | 4071–11,322 6489.4 ± 267.5 | 7810–60,098 27,637.9 ± 3368.6 | 87,200 | 2807–14,838 6329.4 ± 513.9 | 6260–17,481 11,465.6 ± 823.7 | 80,500 |

| Si | – | 324–794 468.1 ± 24.6 | 5420 | – | – | 254,000 | – | – | 295,000 |

| P | 13–330 43.5 ± 12.0 | <10–25 3.7 ± 1.7 | 10 | 4574–117,039 19,628.4 ± 4719.0 | 1684–20,367 7324.9 ± 1225.8 | 2010 | 4979–28,343 8555.9 ± 720.9 | 6478–16,052 10,612.8 ± 614.3 | 930 |

| K | 163–3993 1416.6 ± 180.7 | 800–19,400 6005.0 ± 924.5 | 1350 | 534–2286 1406.7 ± 79.0 | 52–9567 3089.6 ± 737.1 | 16,900 | 373–3092 1202.9 ± 116.0 | 920–4788 2430.5 ± 264.6 | 25,000 |

| Ca | 34,477–170,223 82,897.8 ± 5625.8 | – | 14,600 | 882–20,478 6420.4 ± 884.6 | 5135–63,589 23,869.0 ± 3755.3 | 25,900 | 1494–77,464 15,488.2 ± 2755.3 | 10,804–86,304 50,075.5 ± 4765.4 | 29,600 |

| Ti | <0.2–2.2 1.0 ± 0.1 | 6.1–12.0 9.9 ± 0.4 | 0.49 | 9.5–181 37.8 ± 6.9 | 4.4–136.6 25.6 ± 8.0 | 4400 | 13–226 47.9 ± 9.8 | 16–65 33.4 ± 3.2 | 4500 |

| Mn | 0.3–1716 63.1 ± 57.1 | <1–24 4.6 ± 1.2 | 34 | 90–514 216.7 ± 16.2 | 273–7590 1322.7 ± 373.2 | 1679 | 64–932 290.9 ± 28.0 | 268–5704 1534.1 ± 453.6 | 1000 |

| Fe | 25–265 142.0 ± 10.1 | 1.9–71.0 11.4 ± 3.6 | 66 | 10,881–29,709 18,172.5 ± 992.2 | 1546–10,109 5508.8 ± 626.6 | 58,100 | 3287–17,688 9220.3 ± 562.7 | 7571–38,740 18,547.9 ± 2038.9 | 46,500 |

| Trace elements | |||||||||

| Li | 2.0–11.3 5.0 ± 0.4 | 8.3–33.0 19.9 ± 2.3 | 1.84 | <4–62 20.9 ± 2.6 | 10–2776 221.3 ± 149.9 | 8.5 | <0.5–21.9 8.6 ± 0.9 | 6.1–24.0 12.3 ± 1.1 | 32 |

| Be | <0.01 | <1 | 0.009 | <0.05–0.55 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.54–1.30 0.82 ± 0.04 | 1.8 | 0.10–0.79 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.29–0.97 0.50 ± 0.04 | 3.8 |

| B | 33–609 129.3 ± 21.4 | 43–565 269.4 ± 48.6 | 10.2 | 1.4–38.5 11.0 ± 1.3 | 10–1994 214.7 ± 127.9 | 70 | 2.4–24.9 8.8 ± 0.9 | 5.9–32.1 16.7 ± 1.9 | 12 |

| V | <0.1–4.1 0.4 ± 0.2 | 8.4–21.0 14.8 ± 0.7 | 0.71 | 9.7–21.2 15.3 ± 0.5 | 4.2–78.3 40.7 ± 5.3 | 129 | 7.2–29.8 14.3 ± 0.9 | 3.7–24.5 9.2 ± 1.2 | 90 |

| Cr | <0.3–1.8 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.3–4.3 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.7 | 13–186 35.5 ± 6.7 | 4.5–33.8 22.9 ± 1.6 | 130 | 10.2–33.1 18.4 ± 1.0 | 7.3–16.3 12.1 ± 0.7 | 83 |

| Co | <0.03–0.42 0.05 ± 0.02 | <1 | 0.15 | 7.1–16.5 10.1 ± 0.4 | 6–224 29.8 ± 14.5 | 22.5 | 1.9–14.9 6.2 ± 0.4 | 6.6–15.1 9.5 ± 0.6 | 18 |

| Ni | <0.9–2.8 0.8 ± 0.2 | <1 | 0.8 | 16.2–34.6 23.1 ± 0.9 | 16–552 58.0 ± 26.4 | 74.5 | 9–70 23.9 ± 2.0 | 19–42 26.3 ± 1.5 | 58 |

| Cu | <0.3–4.6 0.8 ± 0.2 | <5–8.9 5.4 ± 0.7 | 1.48 | 7.2–35.0 14.6 ± 1.2 | 15–47 31.1 ± 1.9 | 75.9 | 5–48 12.4 ± 1.6 | 12–44 23.4 ± 2.2 | 47 |

| Zn | 1.5–20.0 5.0 ± 0.7 | 1.6–3.7 2.2 ± 0.1 | 0.6 | 26–277 71.5 ± 10.0 | 19–4329 416.0 ± 261.7 | 208 | 14–128 36.6 ± 4.0 | 23–74 38.7 ± 2.8 | 83 |

| As | <2.3 | 1.1–8.1 4.4 ± 0.4 | 0.6 | 3.5–16.6 6.5 ± 0.5 | <0.8–3.8 1.5 ± 0.3 | 36.3 | 2.1–14.4 6.4 ± 0.5 | <0.9–12.9 5.2 ± 1.0 | 1.7 |

| Se | <5.3 | <1–7.2 3.6 ± 0.4 | 0.07 | <10 | <0.4–1.1 | – | <0.3–0.8 0.04 ± 0.03 | <0.5 | 0.05 |

| Br | <18–135.6 34.1 ± 7.5 | – | 20 | 11–581 73.4 ± 23.2 | <70 | 21.5 | 12.3–44.4 22.5 ± 1.4 | <19 | 2.1 |

| Sr | 129–986 453.3 ± 36.7 | 419–1317 829.8 ± 75.0 | 60 | 18–309 71.1 ± 11.5 | 40–398 144.1 ± 21.0 | 187 | 21–411 82.3 ± 13.3 | 77–371 204.7 ± 23.2 | 340 |

| Y | <0.006 | – | 0.04 | 3.2–7.5 5.5 ± 0.2 | 3.7–18.6 5.6 ± 0.8 | 21.9 | 1.2–9.2 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.4–10.0 7.0 ± 0.4 | 29 |

| Zr | <0.05–0.13 0.07 ± 0.01 | – | 0.04 | 0.4–10.0 | 1–1980 152.9 ± 108.4 | 260 | 0.1–5.6 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7–4.4 2.2 ± 0.3 | 170 |

| Nb | <0.01 | – | 0.002 | 0.01–0.64 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.04–0.21 0.12 ± 0.01 | 13.5 | 0.0004–0.300 0.044 ± 0.012 | 0.009–0.050 0.026 ± 0.003 | 21 |

| Mo | 0.16–1.67 0.60 ± 0.07 | 1.3–9.4 5.8 ± 0.6 | 0.42 | 0.4–7.6 1.2 ± 0.3 | 0.2–1.9 0.5 ± 0.1 | 2.98 | 0.3–8.5 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.2–1.1 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Ag | <0.1 | 6.3–8.2 7.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.05–58.37 8.0 ± 2.8 | <0.01–4.11 0.36 ± 0.23 | 13 | <0.004–0.423 0.023 ± 0.014 | <0.006–35.48 1.80 ± 1.77 | 0.07 |

| Pd | <0.08–0.26 0.03 ± 0.01 | – | 0.03 | 0.2–1.2 0.44 ± 0.04 | 0.1–61.5 4.9 ± 3.4 | 0.4 | 0.07–0.53 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.09–0.22 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.009 |

| Sn | 0.2–5.9 0.9 ± 0.2 | 16–123 40.6 ± 6.5 | 0.5 | 0.1–8.0 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.2–10.0 1.6 ± 0.6 | 4.57 | 0.05–0.47 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.6–3.0 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.5 |

| Sb | 0.06–0.40 0.14 ± 0.02 | <5 | 0.07 | 0.01–2.29 0.27 ± 0.09 | 0.01–0.71 0.09 ± 0.04 | 2.19 | 0.01–0.11 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.03–0.26 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.5 |

| Te | <0.22–0.41 0.03 ± 0.02 | – | – | <0.02–0.18 0.02 ± 0.01 | <0.02–2.5 1.7 ± 1.2 | 0.54 | <0.02–0.10 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.07–1.00 0.22 ± 0.06 | 0.001 |

| I | 3.4–16.6 6.6 ± 0.6 | – | 7 | 2.0–166 24.7 ± 7.4 | <0.1–2.9 0.8 ± 0.2 | 70 | 0.9–18.0 4.6 ± 0.8 | <0.1–158 30.1 ± 8.9 | 0.4 |

| Cs | <0.03 | – | 0.011 | 1.8–5.7 3.6 ± 0.2 | 2.5–7.1 4.1 ± 0.3 | 6.25 | 0.5–3.5 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2–3.9 2.1 ± 0.2 | 3.7 |

| Ba | 2.1–30.1 18.3 ± 1.3 | 12–37 20.5 ± 1.8 | 23 | 19.1–132 51.0 ± 4.3 | 68–6500 676.5 ± 325.1 | 522 | 11–662 95.6 ± 23.7 | 88–303 174.6 ± 16.9 | 650 |

| Ta | <0.03 | – | 0.001 | <0.005 | 0.011–0.063 0.026 ± 0.003 | 1.27 | <0.0002 | 0.013–0.024 0.018 ± 0.001 | 2.5 |

| W | <0.001–0.040 0.007 ± 0.002 | – | 0.1 | <0.001–0.263 0.025 ± 0.011 | <0.002–0.100 0.017 ± 0.005 | 1.99 | <0.001–0.196 0.012 ± 0.007 | 0.01–0.50 0.06 ± 0.02 | 1.3 |

| Os | <0.07 | – | – | 0.002–0.067 0.011 ± 0.003 | <0.001–0.018 0.002 ± 0.001 | – | 0.002–0.007 0.003 ± 0.001 | <0.001–0.012 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.0002 |

| Ir | <0.001 | – | – | <0.01 | <0.001–0.073 0.007 ± 0.005 | – | <0.0003 | <0.0005 | 0.00065 |

| Pt | <0.001 | – | 0.1 | <0.05 | <0.001–0.207 0.020 ± 0.012 | – | <0.002–0.014 0.001 ± 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| Au | <0.2 | – | 2 | <0.010–0.015 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.03–0.17 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.004 | <0.001–0.040 0.001 ± 0.001 | 0.036–0.052 0.046 ± 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Hg | <0.5 | – | 0.07 | 0.02–0.57 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.008–0.039 0.024 ± 0.002 | 0.08 | 0.016–0.051 0.025 ± 0.001 | <0.004–0.050 0.010 ± 0.002 | 0.08 |

| Pb | <0.1 | <5–5.8 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.08 | 4.8–31.0 9.4 ± 1.0 | 6.1–95.8 17.9 ± 5.0 | 61.1 | 2.8–16.1 7.6 ± 0.6 | 7.7–19.7 12.7 ± 0.08 | 16 |

| Bi | <0.05 | – | – | <0.02–1.40 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.07–1.63 0.27 ± 0.10 | 0.85 | 0.03–1.89 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.09–0.35 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.004 |

| Th | <0.026–0.041 0.016 ± 0.003 | – | 0.041 | 2.1–4.5 3.4 ± 0.1 | 2.2–5.0 3.2 ± 0.2 | 12.1 | 0.8–3.6 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.3–5.2 3.0 ± 0.3 | 14 |

| U | <0.01–4.1 0.5 ± 0.2 | – | 0.37 | 0.11–1.00 0.32 ± 0.03 | 0.1–6.0 0.7 ± 0.3 | 3.3 | 0.12–1.41 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.09–0.40 0.23 ± 0.02 | 2.5 |

| Rare and rare-earth elements | |||||||||

| Sc | <0.1–1.1 0.19 ± 0.04 | – | 1.2 | 1.8–4.2 2.8 ± 0.1 | 3.0–6.8 4.6 ± 0.2 | 18.2 | 1.1–4.5 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.0–5.8 3.2 ± 0.2 | 11 |

| Ga | 0.1–1.7 0.9 ± 0.1 | <5 | 0.03 | 6.1–19.4 10.4 ± 0.5 | 6–398 31.2 ± 19.3 | 18.1 | 2.2–24.4 6.3 ± 0.8 | 7.5–23.0 13.3 ± 1.0 | 19 |

| Ge | <0.08 | – | 0.007 | 7.7–15.9 11.5 ± 0.4 | 1.1–3.3 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.23 | 1.6–14.4 6.5 ± 0.5 | 1.2–3.9 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.4 |

| Rb | 0.1–4.0 0.8 ± 0.1 | – | 1.63 | 9.6–37.3 23.8 ± 1.1 | 21–56 39.1 ± 2.3 | 78.5 | 3.1–18.4 8.4 ± 0.7 | 7.5–31.4 17.9 ± 1.7 | 150 |

| Ru | <0.03 | – | – | <0.003–0.086 0.023 ± 0.003 | <0.002–0.016 0.003 ± 0.001 | – | <0.001–0.073 0.014 ± 0.003 | <0.003–0.030 0.010 ± 0.002 | 0.004 |

| Rh | <0.02 | – | 0.09 | <0.002–0.055 0.012 ± 0.002 | <0.001 | – | 0.001–0.047 | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| Cd | <0.1 | <1 | 0.08 | <0.002–3.93 0.20 ± 0.13 | <0.01–3580 248.5 ± 188.5 | 1.55 | <0.002–0.52 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.1–5.9 0.62 ± 0.28 | 0.13 |

| In | <0.03–0.03 | – | <0.001–0.021 0.007 ± 0.001 | <0.001–0.020 0.007 ± 0.002 | – | <0.001–0.012 0.003 ± 0.001 | <0.001–0.032 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.07 | |

| La | <0.01 | – | 0.12 | 3.8–10.8 7.4 ± 0.4 | 2–288 33.9 ± 18.6 | 37.4 | 2.5–8.5 5.3 ± 0.3 | 2.8–18.6 9.4 ± 1.3 | 29 |

| Ce | <0.01 | – | 0.26 | 7.1–22.6 12.4 ± 0.8 | 6.6–29.6 15.5 ± 1.5 | 73.6 | 5.2–18.1 11.5 ± 0.6 | 7.5–25.7 13.6 ± 1.2 | 70 |

| Pr | <0.017–0.019 | – | 0.04 | 1.2–2.9 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0–3.4 1.8 ± 0.2 | 8 | 0.7–2.4 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.1–5.4 2.7 ± 0.3 | 7 |

| Nd | <0.030–0.039 | – | 0.15 | 5.1–12.6 8.8 ± 0.4 | 4.4–13.7 7.7 ± 0.6 | 32.2 | 2.7–9.5 6.3 ± 0.3 | 5.3–28.1 13.2 ± 1.6 | 30 |

| Sm | <0.02 | – | 0.036 | 1.2–2.6 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.4–2.6 1.8 ± 0.1 | 6.12 | 0.6–2.4 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6–4.4 2.7 ± 0.2 | 7 |

| Eu | <0.02 | – | 0.01 | 0.25–0.60 0.47 ± 0.02 | 0.30–1.13 0.46 ± 0.04 | 1.29 | 0.13–0.78 0.35 ± 0.02 | 0.41–0.99 0.63 ± 0.03 | 1.2 |

| Gd | <0.04 | – | 0.04 | 1.3–2.6 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3–2.5 1.8 ± 0.1 | 5.25 | 0.5–2.5 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.8–4.1 2.8 ± 0.1 | 7 |

| Tb | <0.02 | – | 0.006 | 0.03–0.35 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.14–0.27 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.82 | 0.06–0.36 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.21–0.47 0.32 ± 0.01 | 1 |

| Dy | <0.04 | – | 0.03 | 0.8–1.7 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.8–2.5 1.3 ± 0.1 | 4.25 | 0.3–1.9 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2–2.6 1.8 ± 0.1 | 4.6 |

| Ho | <0.01 | – | 0.007 | <0.01–0.28 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.13–0.63 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.05–0.33 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.18–0.42 0.29 ± 0.02 | 1.3 |

| Er | 0.012–0.046 0.028 ± 0.002 | – | 0.02 | 0.29–0.75 0.52 ± 0.02 | 0.4–2.6 0.6 ± 0.1 | 2.23 | 0.12–0.88 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.4–1.1 0.7 ± 0.1 | 3.1 |

| Tm | <0.013–0.014 | – | 0.003 | <0.002–0.062 0.029 ± 0.004 | 0.03–0.48 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.38 | 0.002–0.090 0.030 ± 0.003 | 0.04–0.12 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.5 |

| Yb | <0.11 | – | 0.02 | <0.01–0.52 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.2–4.2 0.6 ± 0.2 | 2.11 | 0.08–0.61 0.25 ± 0.02 | 0.27–0.72 0.47 ± 0.04 | 0.3 |

| Lu | <0.001 | – | 0.024 | <0.001–0.050 0.022 ± 0.003 | 0.02–0.83 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.35 | <0.001–0.078 0.023 ± 0.003 | 0.03–0.10 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.8 |

| Hf | 0.10–0.21 0.17 ± 0.01 | – | 0.006 | 0.03–0.62 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.1–31.3 2.8 ± 1.8 | 4.04 | 0.02–0.20 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.04–0.26 0.13 ± 0.02 | 1 |

| Re | <0.1 | – | 0.0004 | <0.0001–0.006 | <0.001 | – | <0.0001–0.005 | <0.0003 | 0.0007 |

| Tl | <0.05 | – | 0.007 | <0.004–0.20 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.06–0.22 0.13 ± 0.01 | 0.53 | 0.01–0.18 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.04–0.14 0.08 ± 0.01 | 1 |

| Element | Suspended Matter | Bottom Sediments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC Range in Districts 1–3 (Russia) | AC Range in Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan) | Range of AC in Suspended Matter (rivers of Russia and Azerbaijan) | AC Range in Districts 1–3 (Russia) | AC Range in Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan) | AC Range in Bottom Sediments (Rivers of the Russian Federation and Azerbaijan) | |

| Li | 5.5·103 | 1.2·103–8.4·104 | n × 103–n × 104 | 2.5·102–2.2·104 | 7.3·102 | n × 102–n × 104 |

| Be | 5.5·104 | 5.0·102–1.3·103 | n × 102–n × 104 | 7.9·104 | 3.0·102–1.0·103 | n × 102–n × 104 |

| B | 6.3·101 | 2.3·102–3.5·103 | n × 101–n × 103 | 7.2·101 | 5.6·101–1.4·102 | n × 101–n × 102 |

| Na | 5.3·101 | 3.7·101 | n × 101 | 7.6·100–3.7·101 | 9.9·100–3.6·101 | n × 100–n × 101 |

| Mg | 3.4·104 | WND | n × 104 | 7.2·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Al | 3.2·105–4.2·106 | 2.8·105–2.1·106 | n × 105–n × 106 | 2.3·103–5.5·105 | 6.2·105–2.2·106 | n × 103–n × 106 |

| P | 3.5·105 | 8.1·105 | n × 105 | 1.5·104–3.8·105 | 6.4·105 | n × 104–n × 105 |

| K | 5.7·102–3.3·103 | 6.5·101–5.0·102 | n × 101–n × 103 | 9.3·101–2.3·103 | 2.5·102–1.2·103 | n × 101–n × 103 |

| Ca | 2.5·101–1.2·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 | 8.8·100–4.3·101 | WND | n × 100–n × 101 |

| Sc | 3.8·103–1.8·104 | WND | n × 103–n × 104 | 1.0·103–1.1·104 | WND | n × 103–n × 104 |

| Ti | 8.2·104 | 7.2·102–1.1·104 | n × 102–n × 104 | 5.9·103–6.5·104 | 5.4·103 | n × 103–n × 104 |

| V | 5.2·103–9.7·104 | 5.0·102–3.7·103 | n × 102–n × 104 | 1.8·103–7.2·104 | 4.4·102–1.2·103 | n × 102–n × 104 |

| Cr | 4.3·104–1.0·105 | 7.9·103 | n × 103–n × 105 | 5.7·103–3.4·104 | 5.6·103 | n × 103–n × 104 |

| Mn | 2.9·102–3.0·105 | 3.2·105 | n × 102–n × 105 | 3.7·101–2.1·105 | 2.7·105 | n × 101–n × 105 |

| Fe | 4.4·105 | 8.1·105 | n × 105 | 1.2·104–1.3·105 | 5.5·105–4.0·106 | n × 105–n × 106 |

| Co | 3.9·104–2.4·105 | 6.0·103–2.2·105 | n × 103–n × 105 | 4.5·103–6.3·104 | 6.6·103–1.5·104 | n × 103–n × 104 |

| Ni | 1.6·104 | 1.6·104–5.5·105 | n × 104–n × 105 | 3.2·103–1.0·104 | 4.2·104 | n × 103–n × 104 |

| Cu | 7.6·103–2.4·104 | 5.3·103 | n × 103–n × 104 | 1.4·103–1.7·104 | 4.9·103 | n × 103–n × 104 |

| Zn | 1.7·104 | 1.1·104–1.1·106 | n × 104–n × 106 | 7.0·102–9.3·103 | 2.0·104 | n × 102–n × 104 |

| Ga | 6.1·104 | 1.2·103–8.0·104 | n × 103–n × 104 | 1.3·103–2.2·104 | 4.6·103 | n × 103–n × 104 |

| Ge | 9.6·104–2.0·105 | WND | n × 104–n × 105 | 2.0·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| As | 7.2·103 | 7.3·102 | n × 102–n × 103 | 9.1·102 | 8.1·102–1.6·103 | n × 102–n × 103 |

| Se | 1.8·103 | 4.0·102 | n × 102–n × 103 | 5.6·101 | 6.9·101–5.0·102 | n × 101–n × 102 |

| Br | 6.1·102–4.2·103 | WND | n × 102–n × 103 | 9.0·101–6.8·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 |

| Rb | 9.3·103–9.6·104 | WND | n × 103–n × 104 | 7.8·102–3.1·104 | WND | n × 102–n × 104 |

| Sr | 3.1·102 | WND | n × 102 | 2.1·101–1.6·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 |

| Y | 5.3·105–1.2·106 | WND | n × 105–n × 106 | 2.0·105 | WND | n × 105 |

| Zr | 8.0·103–7.7·104 | WND | n × 103–n × 104 | 7.7·102–2.0·103 | WND | n × 102–n × 103 |

| Nb | 4.5·103 | WND | n × 103 | 4.0·101 | WND | n × 101 |

| Mo | 1.0·102–2.9·103 | 2.0·102 | n × 102–n × 103 | 1.8·102–1.9·103 | 1.5·102 | n × 102–n × 103 |

| Ru | 1.0·102–2.8·103 | WND | n × 102–n × 103 | 3.3·101 | WND | n × 101 |

| Rh | 4.6·103 | WND | n × 103 | 5.0·101 | WND | n × 101 |

| Pd | 5.0·102–5.8·105 | WND | n × 102–n × 105 | 8.8·102 | WND | n × 102 |

| Ag | 2.0·101–3.9·104 | 1.6·100–5.0·102 | n × 100–n × 104 | 4.0·101 | 1.0·100–4.3·103 | n × 100–n × 103 |

| Cd | 3.3·101–7.0·102 | 1.0·101–3.6·106 | n × 101–n × 106 | 2.0·101 | 1.0·102–5.9·103 | n × 101–n × 103 |

| In | 3.3·101–7.0·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 | 3.3·101 | WND | n × 101 |

| Sn | 5.0·102–1.3·103 | 8.1·101 | n × 101–n × 102 | 1.7·101–5.0·102 | 3.8·101 | n × 101–n × 102 |

| Sb | 1.7·102–5.7·103 | 2.0·100–1.4·102 | n × 100–n × 103 | 2.5·101–1.7·102 | 6.0·100–5.2·101 | 1.6·100–5.0·102 |

| Te | 9.0·101–4.5·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 | 9.0·101 | WND | n × 101 |

| I | 5.9·102–1.0·104 | WND | n × 102–n × 104 | 5.4·101–2.6·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 |

| Cs | 6.0·104–1.9·105 | WND | n × 104–n × 105 | 1.6·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Ba | 9.0·103 | 5.7·103–1.8·105 | n × 103–n × 105 | 3.7·102–5.2·103 | 8.2·103 | n × 102–n × 103 |

| La | 3.8·104–1.1·105 | WND | n × 104–n × 105 | 2.5·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Ce | 7.1·104–2.3·105 | WND | n × 104–n × 105 | 5.2·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Pr | 7.1·104–1.5·105 | WND | n × 104–n × 105 | 4.1·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Nd | 3.2·105 | WND | n × 105 | 9.0·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Sm | 6.0·104–1.3·105 | WND | n × 104–n × 105 | 3.0·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Eu | 3.2·104 | WND | n × 104 | 6.5·103 | WND | n × 103 |

| Gd | 6.5·104 | WND | n × 104 | 1.3·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| Tb | 7.1·103–1.5·104 | WND | n × 103–n × 104 | 3.0·103 | WND | n × 103 |

| Dy | 4.3·104 | WND | n × 104 | 7.5·103 | WND | n × 103 |

| Ho | 1.0·103–2.8·104 | WND | n × 103–n × 104 | 5.0·103 | WND | n × 103 |

| Er | 2.5·104 | WND | n × 104 | 8.3·103 | WND | n × 103 |

| Tm | 1.5·102–4.4·103 | WND | n × 102–n × 103 | 1.5·102 | WND | n × 102 |

| Yb | 9.1·100–4.7·103 | WND | n × 100–n × 103 | 7.3·102 | WND | n × 102 |

| Lu | 1.0·103–5.0·104 | WND | n × 103–n × 104 | 1.0·103 | WND | n × 103 |

| Hf | 1.0·102–5.0·103 | WND | n × 102–n × 103 | 9.5·101–2.0·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 |

| Ta | 1.6·102 | WND | n × 102 | 6.7·100 | WND | n × 100 |

| W | 7.5·103 | WND | n × 103 | 2.5·101–1.0·103 | WND | n × 101–n × 103 |

| Re | 6.0·100 | WND | n × 100 | 1.0·100 | WND | n × 100 |

| Os | 2.9·101–8.6·102 | WND | n × 101–n × 102 | 2.8·101 | WND | n × 101 |

| Ir | 1.0·104 | WND | n × 104 | 3.0·102 | WND | n × 102 |

| Pt | 5.0·104 | WND | n × 104 | 2.0·103 | WND | n × 103 |

| Au | 7.5·101 | WND | n × 101 | 5.0·101 | WND | n × 101 |

| Hg | 4.0·101–1.1·103 | WND | n × 101–n × 103 | 3.2·102 | WND | n × 102 |

| Tl | 8.0·101–4.0·103 | WND | n × 101–n × 103 | 2.0·102 | WND | n × 102 |

| Pb | 4.8·104–3.1·105 | 1.2·103–1. 7·104 | n × 103–n × 105 | 2.8·104 | 3.4·103 | n × 103–n × 104 |

| Bi | 4.0·102–2.8·104 | WND | n × 102–n × 104 | 6.0·102 | WND | n × 102 |

| Th | 8.1·104–1.1·105 | WND | n × 104–n × 105 | 3.1·104 | WND | n × 104 |

| U | 2.4·102–1.1·104 | WND | n × 102–n × 104 | 2.9·101–1.2·104 | WND | n × 101–n × 104 |

| Element | EF | Element | EF | Element | EF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Districts 1–3 (Russia) | Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan) | Districts 1–3 (Russia) | Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan) | Districts 1–3 (Russia) | Districts 4–5 (Azerbaijan) | |||

| Li | 0.2–5.1 | 0.8–1.8 | Br | 15–510 | 0 | Nd | 0.4–1.4 | 0.3–3.6 |

| Be | 0.03–0.42 | 0.2–0.7 | Rb | 0.2–0.7 | 0.1–0.9 | Sm | 0.4–1.2 | 0.4–2.6 |

| B | 0.3–5.9 | 1.1–10.5 | Sr | 0.1–1.8 | 0.3–5.9 | Eu | 0.4–2.0 | 0.6–3.4 |

| Na | 0.01–0.30 | 0.02–0.25 | Y | 0.3–1.0 | 0.3–1.8 | Gd | 0.4–1.3 | 0.5–2.5 |

| Mg | 0.2–0.5 | 0.4–1.2 | Zr | 0.01–0.14 | 0.01–0.11 | Tb | 0.1–1.1 | 0.5–2.0 |

| Al | 0.1–0.4 | 0.2–1.2 | Nb | 0.002–0.071 | 0.001–0.009 | Dy | 0.4–1.2 | 0.5–2.6 |

| P | 17–232 | 20–48 | Mo | 0.9–29.5 | 0.9–2.0 | Ho | 0.1–0.7 | 0.3–1.6 |

| K | 0.1–0.3 | 0.1–0.7 | Ru | 1.7–91.7 | 2.9–38.8 | Er | 0.2–0.8 | 0.2–1.7 |

| Ca | 0.1–3.0 | 0.4–17.0 | Rh | 1.2–47.4 | 0 | Tm | 0.1–0.5 | 0.1–1.2 |

| Sc | 0.4–1.1 | 0.5–1.6 | Pd | 44–276 | 14–133 | Yb | 1.0–5.6 | 1.3–12.8 |

| Ti | 0.01–0.09 | 0.01–0.05 | Ag | 1.9–1450 | 0.24–2137 | Lu | 0.03–0.23 | 0.1–0.6 |

| V | 0.3–0.8 | 0.1–1.4 | Cd | 0.2–55.8 | 1.2–229.6 | Hf | 0.1–1.1 | 0.1–1.0 |

| Cr | 0.5–4.1 | 0.2–0.9 | In | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–0.7 | Ta | 0 | 0.01–0.04 |

| Mn | 0.2–1.1 | 0.7–29.3 | Sn | 0.1–5.9 | 0.6–7.3 | W | 0.01–0.46 | 0.01–0.47 |

| Fe | 1 | 1 | Sb | 0.1–8.4 | 0.1–1.0 | Os | 29–615 | 24.4–70.9 |

| Co | 0.8–2.8 | 0.9–2.7 | Te | 69–761 | 158–5822 | Au | 1.0–3.7 | 6.4–31.7 |

| Ni | 0.5–2.6 | 0.8–2.2 | I | 16–713 | 46–474 | Hg | 0.7–13.2 | 0.1–2.6 |

| Cu | 0.4–1.6 | 0.7–3.4 | Cs | 1.1–4.3 | 0.8–3.0 | Tl | 0.1–0.9 | 0.1–0.5 |

| Zn | 1.0–6.2 | 0.9–2.9 | Ba | 0.1–0.9 | 0.2–2.5 | Pb | 0.9–3.6 | 1.3–3.9 |

| Ga | 0.9–4.4 | 0.7–7.1 | La | 0.3–1.3 | 0.1–3.1 | Bi | 52–793 | 59–232 |

| Ge | 12.4–28.7 | 3.0–5.6 | Ce | 0.2–1.1 | 0.2–2.2 | Th | 0.3–1.0 | 0.2–1.4 |

| As | 6.3–18.0 | 2.5–11.8 | Pr | 0.3–1.4 | 0.2–3.1 | U | 0.1–1.7 | 0.04–0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chuzhikova, O.; Tabunshchik, V.; Gorbunov, R.; Proskurnin, V.; Gorbunova, T.; Mirzoeva, N.; Tikhonova, E.; Mironov, O.; Paraskiv, A.; Voitsekhovskaya, V.; et al. Geochemistry of Water and Bottom Sediments in Mountain Rivers of the North-Eastern Caucasus (Russia and Azerbaijan). Water 2025, 17, 3390. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233390

Chuzhikova O, Tabunshchik V, Gorbunov R, Proskurnin V, Gorbunova T, Mirzoeva N, Tikhonova E, Mironov O, Paraskiv A, Voitsekhovskaya V, et al. Geochemistry of Water and Bottom Sediments in Mountain Rivers of the North-Eastern Caucasus (Russia and Azerbaijan). Water. 2025; 17(23):3390. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233390

Chicago/Turabian StyleChuzhikova, Olga, Vladimir Tabunshchik, Roman Gorbunov, Vladislav Proskurnin, Tatiana Gorbunova, Natalia Mirzoeva, Elena Tikhonova, Oleg Mironov, Artem Paraskiv, Veronika Voitsekhovskaya, and et al. 2025. "Geochemistry of Water and Bottom Sediments in Mountain Rivers of the North-Eastern Caucasus (Russia and Azerbaijan)" Water 17, no. 23: 3390. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233390

APA StyleChuzhikova, O., Tabunshchik, V., Gorbunov, R., Proskurnin, V., Gorbunova, T., Mirzoeva, N., Tikhonova, E., Mironov, O., Paraskiv, A., Voitsekhovskaya, V., Kerimov, I., & Chuprina, E. (2025). Geochemistry of Water and Bottom Sediments in Mountain Rivers of the North-Eastern Caucasus (Russia and Azerbaijan). Water, 17(23), 3390. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233390