Coordinated Development of Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in the Yellow River Basin: A Comprehensive Assessment Based on Multi-Method Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.1.1. Water

2.1.2. Energy

2.1.3. Agriculture

2.1.4. Ecological Environment

2.2. Data Sources and Indicator System

2.2.1. Data Sources

2.2.2. Data Processing

2.2.3. Indicator System

2.3. Methodological Framework

2.3.1. Entropy Weight Method

2.3.2. Coupling Coordination Degree Model

2.3.3. Center of Gravity Migration Model

2.3.4. Principal Component Analysis

Data Standardization

Correlation Coefficient Matrix Calculation

Eigenvalue and Eigenvector Solution

Principal Component Extraction

Variance Contribution Rate Calculation

Principal Component Selection Criteria

Principal Component Score Calculation

Comprehensive Evaluation Index

2.3.5. Obstacle Factor Diagnosis Model

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Evolution of WEFE Subsystems

3.2. Coupling Coordination Analysis

3.3. Center of Gravity Migration Analysis

3.4. Pairwise Coupling Relationships

3.5. Principal Component Analysis Results

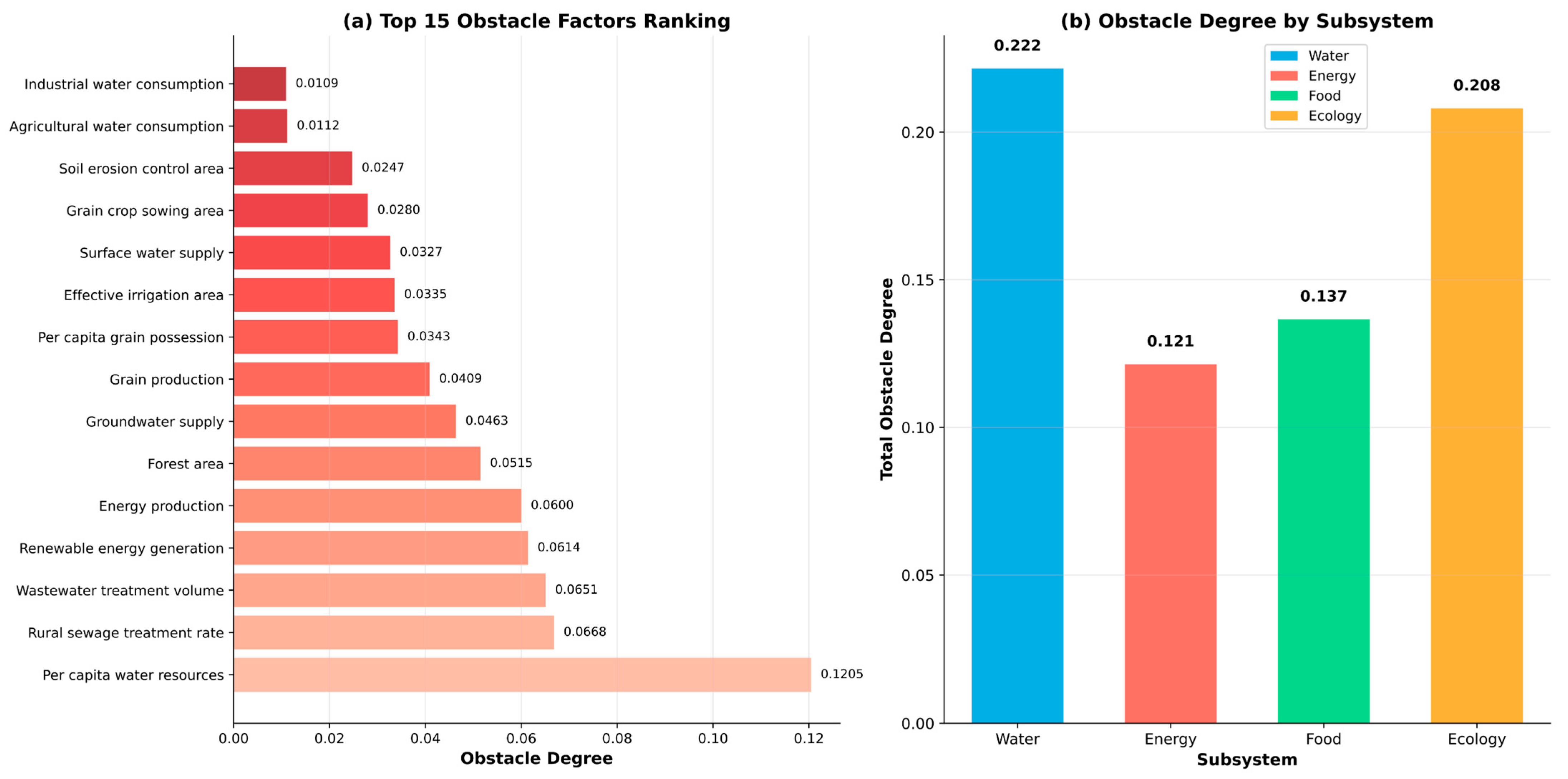

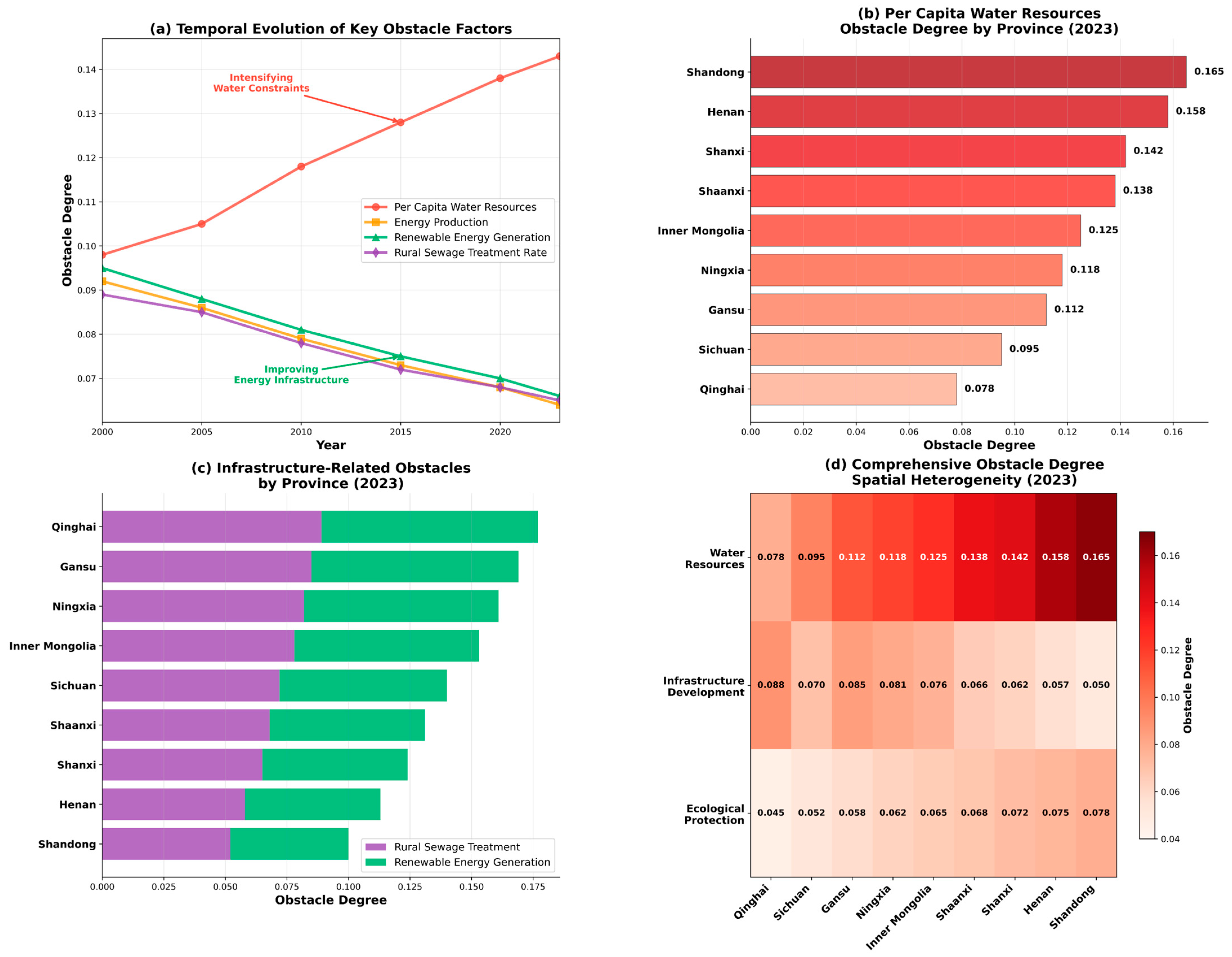

3.6. Obstacle Factor Diagnosis

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Significance of Main Findings

4.2. Practical Value of Research Results

4.2.1. Water Resource Management Policy Insights

4.2.2. Energy Development Policy Guidance

4.2.3. Agricultural Development Policy Optimization

4.2.4. Ecological Protection Policy Improvement

4.3. Comparative Analysis with Existing Research

4.3.1. Comparison of Obstacle Factor Identification

4.3.2. Comparison of Coupling Coordination Degree Analysis

4.3.3. Comparison of Spatial Evolution Analysis

4.3.4. Cross-Regional Coordination Mechanisms:

5. Conclusions and Prospects

5.1. Main Research Findings

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

5.2.1. Limitations

5.2.2. Deepening Mechanism Research

5.2.3. Expanding Research Scales

5.2.4. Strengthening Application Orientation

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, S.; Zhang, F.; Engel, B.A.; Wang, Y.; Guo, P.; Li, Y. A distributed robust optimization model based on water-food-energy nexus for irrigated agricultural sustainable development. J. Hydrol. 2022, 606, 127394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, H. Understanding the Nexus. Background Paper for the Bonn2011 Conference: The Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus; Stockholm Environment Institute: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, E.M.; Bruce, E.; Boruff, B.; Duncan, J.M.; Horsley, J.; Pauli, N.; McNeill, K.; Neef, A.; Van Ogtrop, F.; Curnow, J.; et al. Sustainable development and the water–energy–food nexus: A perspective on livelihoods. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 54, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J. Assessment and enhancement pathways of the water-energy-food-economy-ecosystem nexus in China’s yellow river basin. Energy 2025, 316, 134492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yupanqui, C.; Dias, N.; Goodarzi, M.; Sharma, S.; Vagheei, H.; Mohtar, R. A review of water-energy-food nexus frameworks, models, challenges and future opportunities to create an integrated, national security-based development index. Energy Nexus 2025, 18, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejnowicz, A.P.; Thorn, J.P.R.; Giraudo, M.E.; Sallach, J.B.; Hartley, S.E.; Grugel, J.; Pueppke, S.G.; Emberson, L. Appraising the Water-Energy-Food Nexus from a Sustainable Development Perspective: A Maturing Paradigm? Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Water–energy–food nexus in the Yellow River basin of China under the influence of multiple policies. Land 2024, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teutschbein, C.; Jonsson, E.; Todorović, A.; Tootoonchi, F.; Stenfors, E.; Grabs, T. Future drought propagation through the water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus—A nordic perspective. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 128963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sušnik, J.; Masia, S.; Teutschbein, C. Water as a key enabler of nexus systems (water–energy–food). Camb. Prism. Water 2023, 1, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, C.; Carter, N.T. Energy-Water Nexus: The Water Sector’s Energy Use; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Erb, K.-H.; Haberl, H.; Plutzar, C. Dependency of global primary bioenergy crop potentials in 2050 on food systems, yields, biodiversity conservation and political stability. Energy Policy 2012, 47, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazal, A.A.; Jakrawatana, N.; Silalertruksa, T.; Gheewala, S.H. Water-energy-food nexus review for biofuels assessment. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2022, 11, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekchanov, M.; Ringler, C.; Mueller, M. Ecosystem services in the water-energy-food nexus. Change Adapt. Socio-Ecol. Syst. 2015, 2, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragkaki, A.; Koukianaki, E.A.; Lilli, M.A.; Efstathiou, D.; Nikolaidis, N.P. Optimizing the water-ecosystem-food nexus using nature-based solutions at the basin scale. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1386925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.K.; Sikka, A.K.; Alam, M.F. Water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus in India—A review of relevant studies, policies, and programmes. Front. Water 2023, 5, 1128198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalvani, S.R.; Celico, F. Analysis of pros and cons in using the water–energy–food nexus approach to assess resource security: A review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, K.; Chowdhury, M.; Dutta, S.; Satpute, A.N.; Jha, A.; Khose, S.; Gupta, V.; Das, S. Synergising agricultural systems: A critical review of the interdependencies within the water-energy-food nexus for sustainable futures. Water-Energy Nexus 2025, 8, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torhan, S.; Grady, C.A.; Ajibade, I.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Hernandez, R.R.; Musah-Surugu, J.I.; Nunbogu, A.M.; Segnon, A.C.; Shang, Y.; Ulibarri, N.; et al. Tradeoffs and synergies across global climate change adaptations in the food-energy-water nexus. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Water-Energy-Food Nexus: A New Approach in Support of Food Security and Sustainable Agriculture; FAO Technical Brief; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, X.; Liu, T.; Ling, Y.; Peng, J. Managing the water-agriculture-environment-energy nexus: Trade-offs and synergies in an arid area of northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 295, 108776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Chen, Y.; He, P.; Ren, Y.; Yan, P.; Li, J. Multi-level decisions for addressing trade-off in the cross-regional water-environment-agriculture interactive system under constraint of water ecological carrying capacity. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 121940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Cheng, W. Land use conflict identification coupled with ecological protection priority in Jinan city, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, S.; Yin, Y.; Wang, K.; Sun, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, J. Water-food-carbon nexus related to the producer–consumer link: A review. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 938–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewöhner, J.; Bruns, A.; Haberl, H.; Hostert, P.; Krueger, T.; Lauk, C.; Lutz, J.; Müller, D.; Nielsen, J.Ø. Land Use Competition. Ecological, Economic and Social Perspective, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, J. Analysis of coupling coordination development and obstacle factors in the water-energy-carbon-ecological environment nexus across China’s yellow river basin. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, S.; Qian, Z. Adaptability Analysis and Spatial Correlation Characteristics of Water-Energy-Food-Ecology System in the Yellow River Basin from the Perspective of Symbiosis. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5114696 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. Spatial and temporal distribution and influencing factors of ‘water-energy-food-ecology’ system resilience. Land 2025, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Han, J.; Wu, Q.; Xie, W.; He, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, E. The coupling coordination and spatiotemporal evolution of industrial water-energy-CO2 in the Yellow River basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Xuan, X.; He, Q. A water-energy nexus analysis to a sustainable transition path for ji-shaped bend of the Yellow River, china. Ecol. Inf. 2022, 68, 101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Tang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X. Water scarcity under various socio-economic pathways and its potential effects on food production in the Yellow River basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 21, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, Y.; Kou, J.; Yang, H.; Xue, B.; Gou, X. Scenario analysis of water-land-food synergy in nine provinces along the Yellow River. Adv. Earth Sci. 2023, 38, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Xu, H. Does agricultural water-saving policy improve food security? Evidence from the Yellow River basin in China. Water Policy 2023, 25, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Yu, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Matching supply and demand for ecosystem services in the Yellow River basin, china: A perspective of the water-energy-food nexus. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 384, 135469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, L. Development and synergetic evolution of the water–energy–food nexus system in the Yellow River Basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 65549–65564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, A.; Liu, T.; Du, S.; Liang, S. Coordinated analysis and evaluation of water–energy–food coupling: A case study of the Yellow River basin in shandong province, china. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 148, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Sun, H.; Bai, H. Coupling coordination evaluation of water-energy-food and poverty in the Yellow River basin, China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 614, 128461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Song, J.; Li, Q. Solving the sustainable development dilemma in the Yellow River basin of China: Water-energy-food linkages. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 490, 144797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Li, X.; Yin, D.; Li, T.; Cai, X.; Wei, J.; Wang, G. Revealing the water-energy-food nexus in the upper yellow river basin through multi-objective optimization for reservoir system. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 682, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X. An evaluation of the coupling coordination degree of an urban economy–society–environment system based on a multi-scenario analysis: The case of chengde city in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Wan, S.; Liu, J.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, S. Coupling coordination degree and influencing factors of forestry modernization and high quality economic development: An empirical study from provincial panel in China. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1436292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hong, S. Multi-dimensional analysis of urban expansion patterns and their driving forces based on the center of gravity-GTWR model: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 1076–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Tian, S.; Yuan, X.; Ma, Q.; Xu, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, C. Multicity comparative assessment and optimized management path of sustainability of the economy–energy–environment system: A case study of core cities in China’s three major economic circles. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooren, C.E.; Munaretto, S.; La Jeunesse, I.; Sievers, E.; Hegger, D.L.T.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Hüesker, F.; Cirelli, C.; Canovas, I.; Mounir, K.; et al. Water–energy–food–ecosystem nexus: How to frame and how to govern. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 2313–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hua, E.; Guan, J.; Engel, B.A.; Liu, R.; Bai, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, Y. Development of a method to assess synergy and competition for water use among water-energy-food nexus in the Yellow River basin: Water quantity-quality dimensions. J. Hydrol. 2024, 639, 131607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javan, K.; Altaee, A.; BaniHashemi, S.; Darestani, M.; Zhou, J.; Pignatta, G. A review of interconnected challenges in the water–energy–food nexus: Urban pollution perspective towards sustainable development. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, G.; Wang, H.; Cai, S.; Cui, W. Coupling coordination analysis of resources, economy, and ecology in the Yellow River basin. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 156, 111133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.; Yu, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.; Li, X. A comprehensive evaluation framework of water-energy-food system coupling coordination in the Yellow River basin, china. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Fu, Y.; Lu, B.; Li, H.; Qu, Y.; Ibrahim, H.; Wang, J.; Ding, H.; Ma, S. Coupling coordination evaluation and optimization of water–energy–food system in the Yellow River basin for sustainable development. Systems 2025, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subsystem | Indicators | Unit | Indicators Type | Subsystem Weight | System Weight | Sum of System Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Per capita water resources | m3 | Positive | 0.3502 | 0.1095 | 0.3126 |

| Per capita water consumption | m3 | Negative | 0.0244 | 0.0076 | ||

| Per capita wastewater discharge | t | Negative | 0.0242 | 0.0076 | ||

| Surface water supply | 108 m3 | Positive | 0.1168 | 0.0365 | ||

| Groundwater supply | 108 m3 | Positive | 0.1711 | 0.0535 | ||

| Industrial water consumption | 108 m3 | Negative | 0.0403 | 0.0126 | ||

| Agricultural water consumption | 108 m3 | Negative | 0.2223 | 0.0696 | ||

| Ecological water consumption | 108 m3 | Positive | 0.0506 | 0.0158 | ||

| Energy | Total energy production | 104 tce | Positive | 0.3077 | 0.0602 | 0.1957 |

| Total energy consumption | 104 tce | Negative | 0.0267 | 0.0052 | ||

| Energy consumption in agriculture | 104 tce | Negative | 0.0608 | 0.0119 | ||

| Rural electricity consumption | 108 kWh | Positive | 0.2962 | 0.0580 | ||

| Renewable energy generation | 104 tce | Positive | 0.3086 | 0.0604 | ||

| Food | Total grain production | 104 t | Positive | 0.2766 | 0.0468 | 0.1692 |

| Per capita grain possession | kg | Positive | 0.2003 | 0.0339 | ||

| Grain crop sowing area | 103 ha | Positive | 0.2121 | 0.0359 | ||

| Effective irrigation area | 103 ha | Positive | 0.2482 | 0.0420 | ||

| Fertilizer application | 104 t | Negative | 0.0629 | 0.0106 | ||

| Ecosystem | Total sewage treatment | 104 t | Positive | 0.1911 | 0.0616 | 0.3225 |

| Soil erosion control area | 103 ha | Positive | 0.0882 | 0.0285 | ||

| Industrial waste gas emission | 108 m3 | Negative | 0.0047 | 0.0015 | ||

| Urban sewage treatment rate | % | Positive | 0.0484 | 0.0156 | ||

| Rural sewage treatment rate | % | Positive | 0.2027 | 0.0654 | ||

| Forest area | 104 ha | Positive | 0.1706 | 0.0550 | ||

| Timber production | 104 m3 | Negative | 0.2942 | 0.0949 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, J.; Manevski, K.; Plauborg, F.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Berbel, J. Coordinated Development of Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in the Yellow River Basin: A Comprehensive Assessment Based on Multi-Method Integration. Water 2025, 17, 3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223331

Yao J, Manevski K, Plauborg F, Sun Y, Wang L, Zhang W, Berbel J. Coordinated Development of Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in the Yellow River Basin: A Comprehensive Assessment Based on Multi-Method Integration. Water. 2025; 17(22):3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223331

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Jingwei, Kiril Manevski, Finn Plauborg, Yangbo Sun, Lingling Wang, Wenmin Zhang, and Julio Berbel. 2025. "Coordinated Development of Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in the Yellow River Basin: A Comprehensive Assessment Based on Multi-Method Integration" Water 17, no. 22: 3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223331

APA StyleYao, J., Manevski, K., Plauborg, F., Sun, Y., Wang, L., Zhang, W., & Berbel, J. (2025). Coordinated Development of Water–Energy–Food–Ecosystem Nexus in the Yellow River Basin: A Comprehensive Assessment Based on Multi-Method Integration. Water, 17(22), 3331. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223331