Freshwater Phenanthrene Removal by Three Emergent Wetland Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

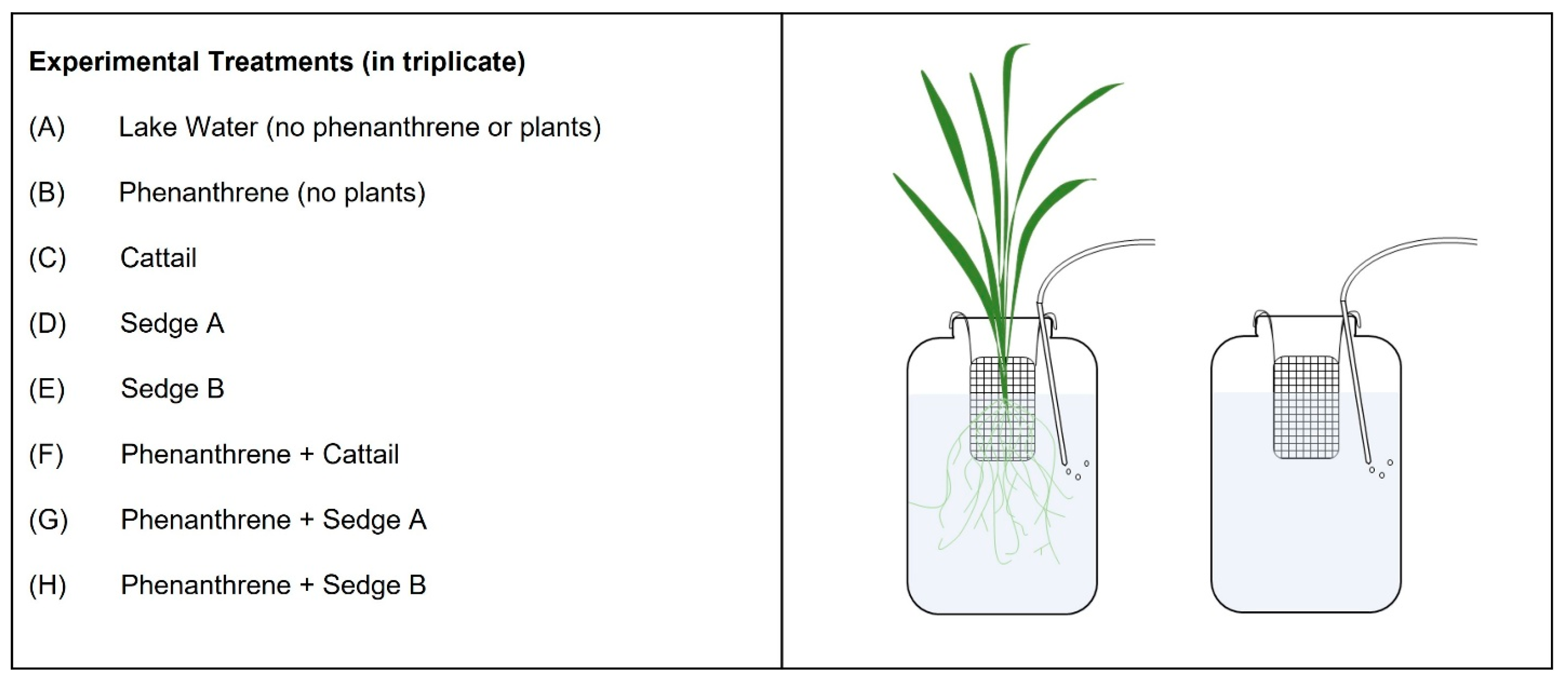

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Basic Water Quality

2.4. Phenanthrene

2.4.1. Extraction

2.4.2. Quantification

2.5. Plant Growth

2.6. Microbial Biofilm

2.6.1. Adenosine Triphosphate

2.6.2. Respirometry

2.7. Statistical Analyses

2.7.1. Basic Water Quality

2.7.2. Phenanthrene

2.7.3. Plant Growth

2.7.4. Microbial Biofilm

3. Results

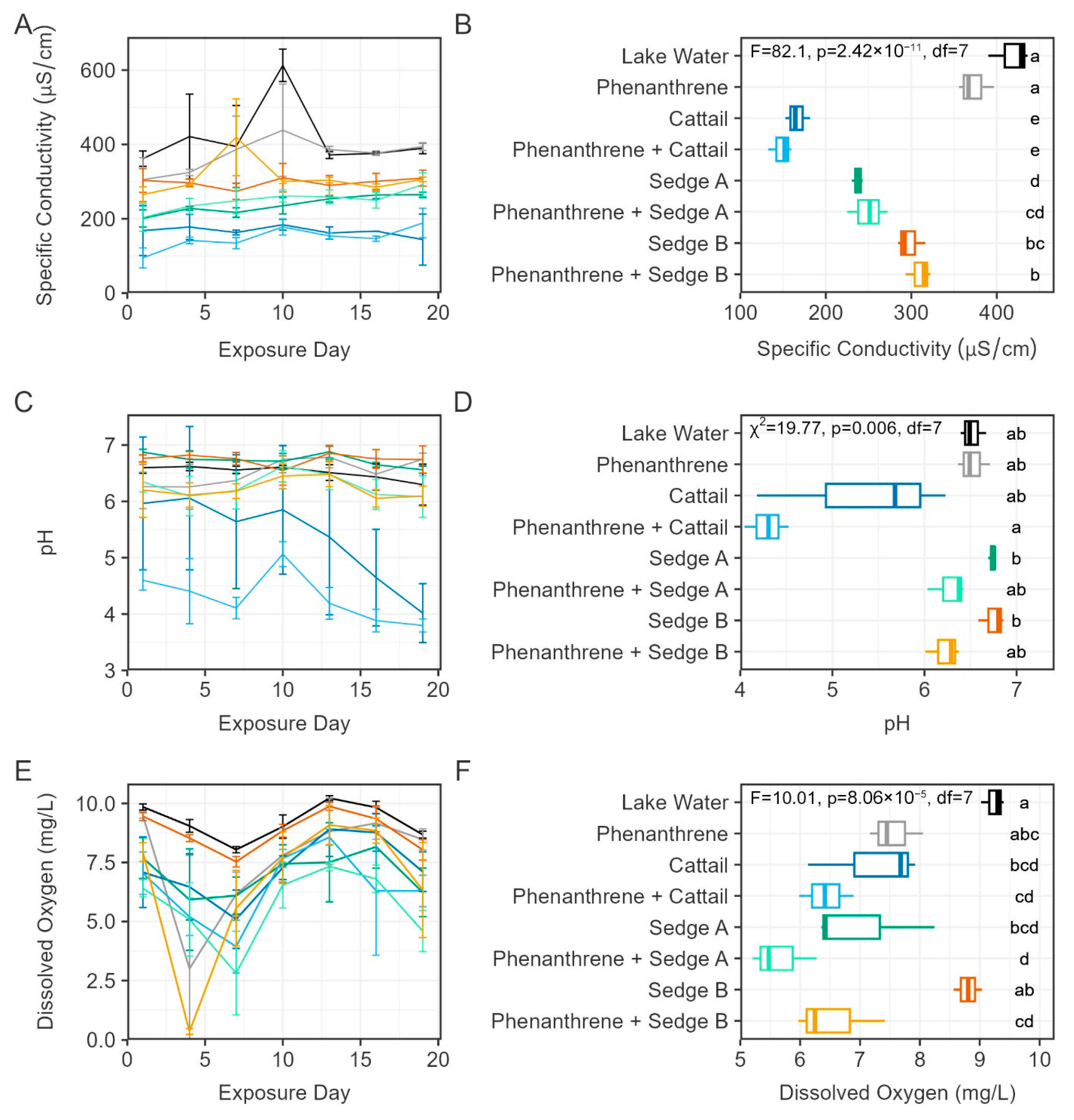

3.1. Basic Water Quality

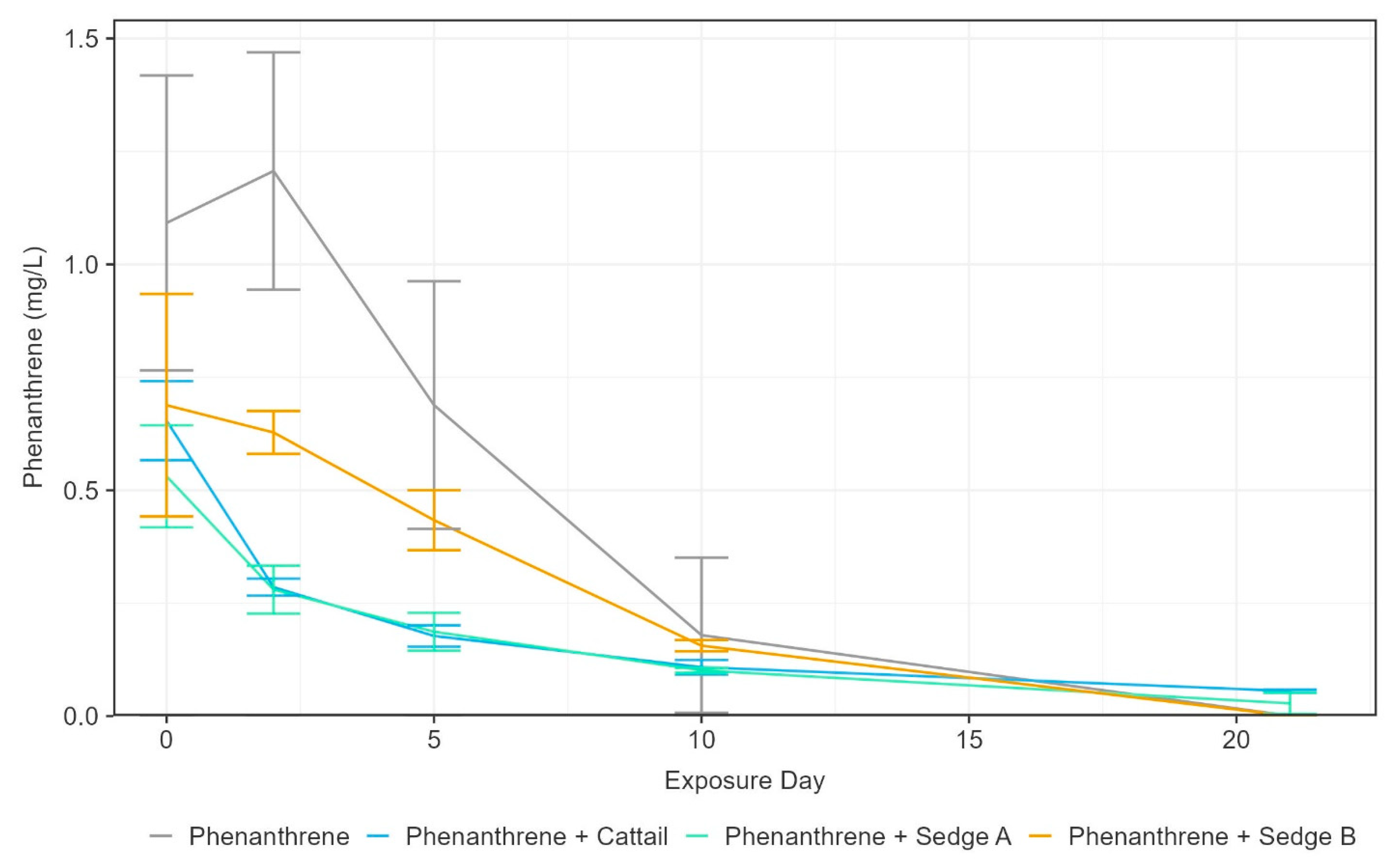

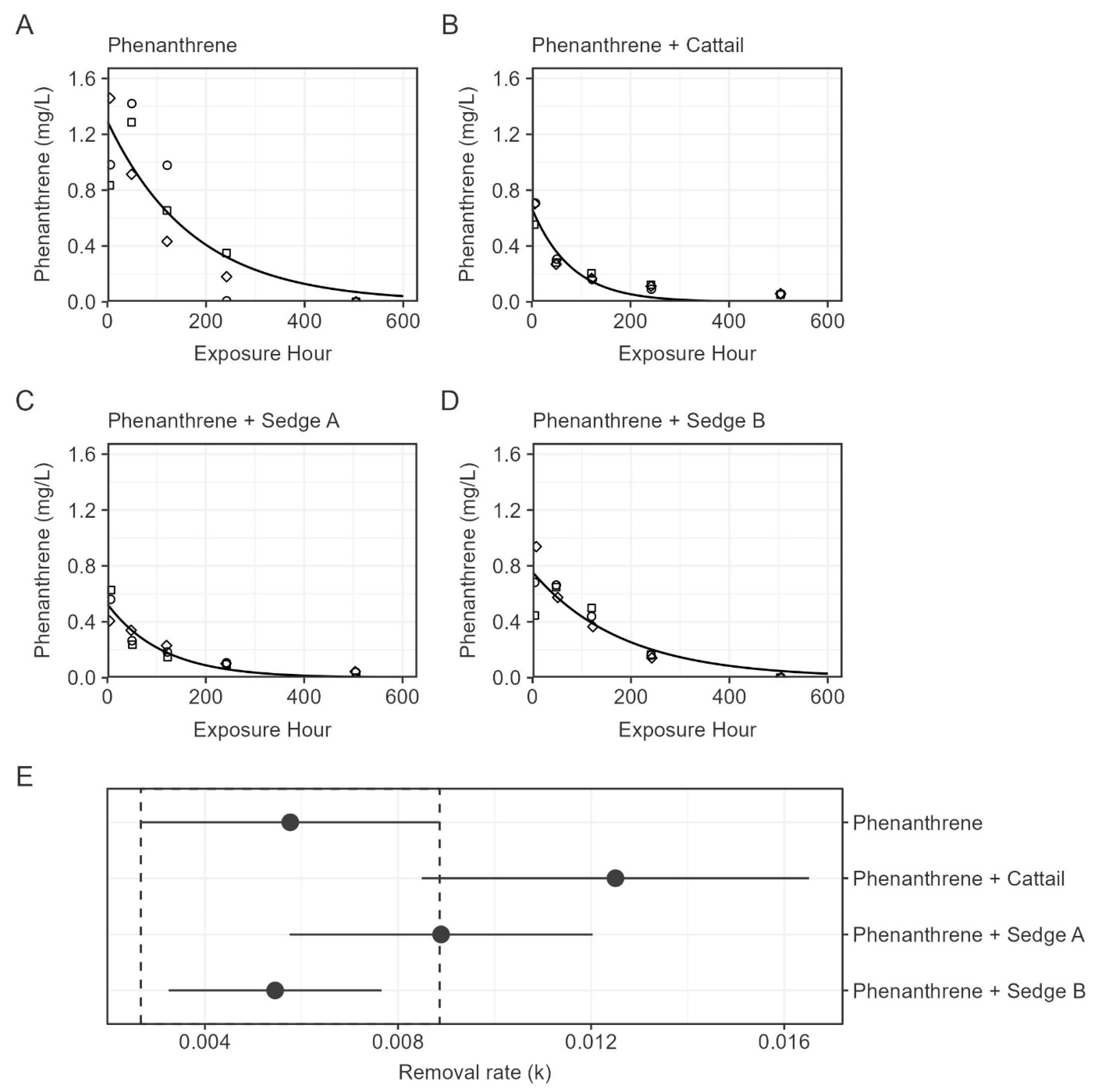

3.2. Phenanthrene

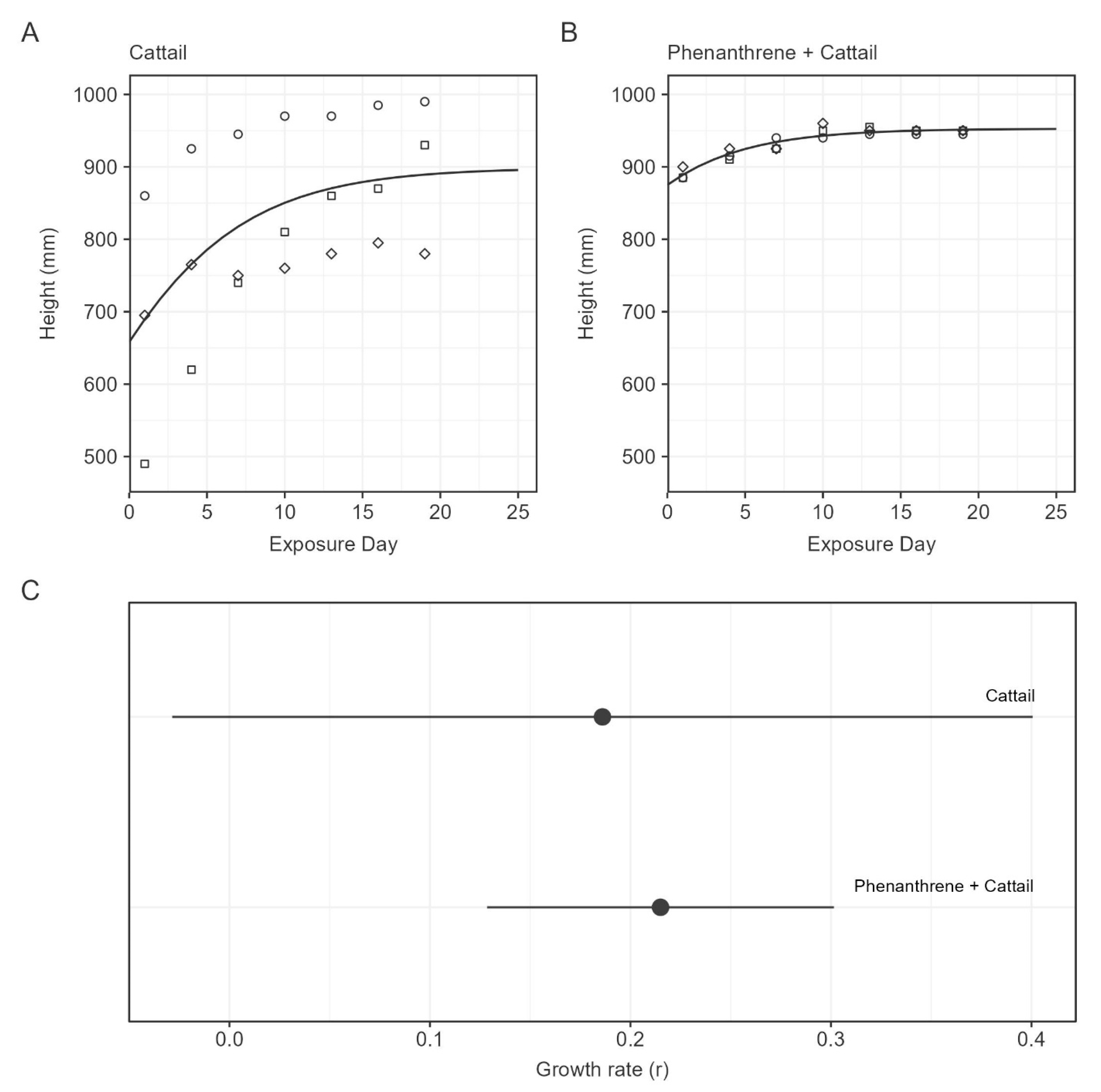

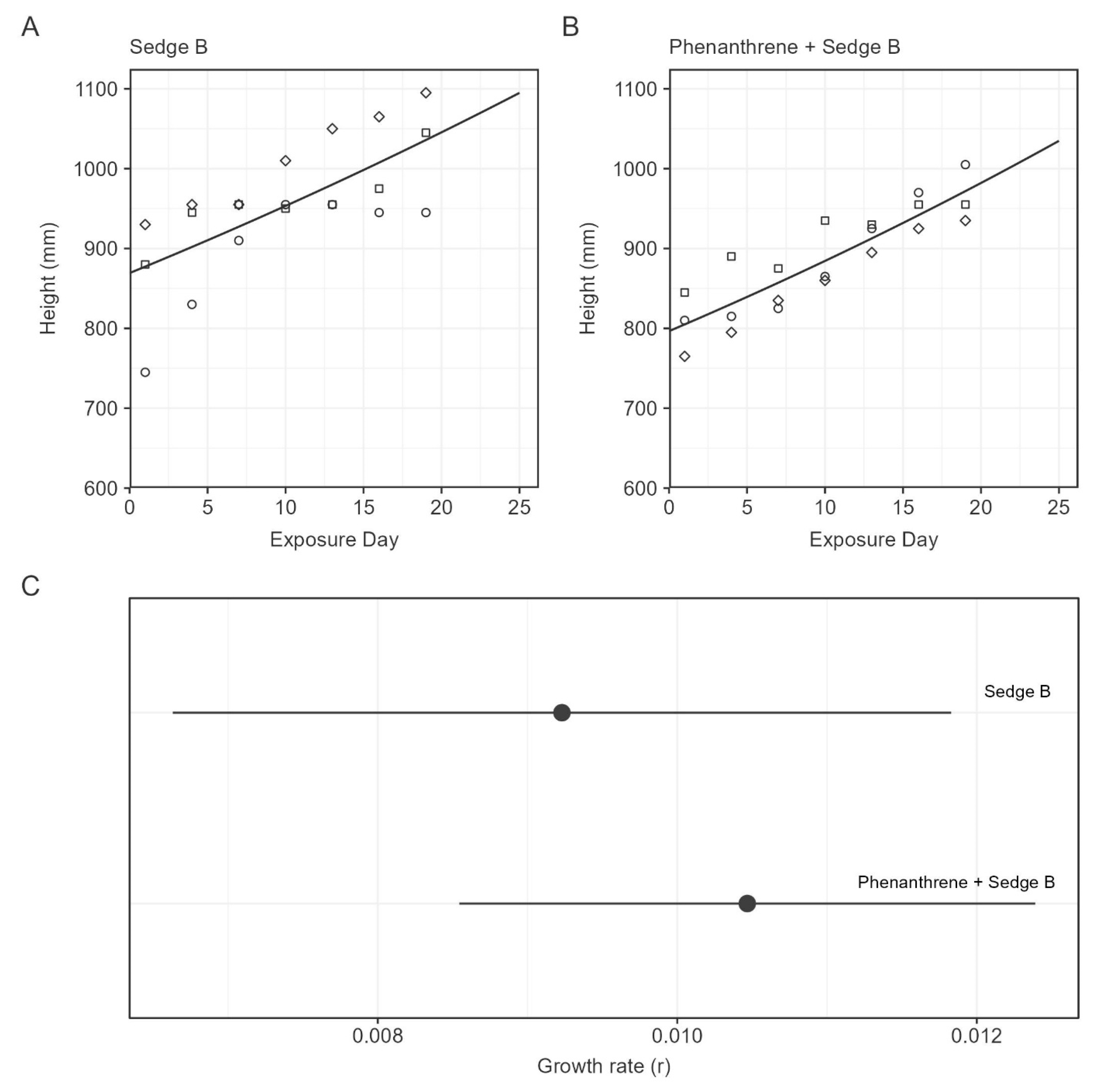

3.3. Plant Growth

3.4. Microbial Biofilm

3.4.1. Adenosine Triphosphate

3.4.2. Respirometry

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CCME | Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| EFW | Engineered Floating Wetland |

| FLOWTER | Floating Wetland Treatments to Enhance Remediation |

| IISD-ELA | International Institute for Sustainable Development Experimental Lakes Area |

| PAC | Polycyclic Aromatic Compound |

References

- Zhu, X.; Venosa, A.D.; Suidan, M.T.; Lee, K. Guidelines for the Bioremediation of Marine Shorelines and Freshwater Wetlands; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.; Nagarajan, K.; Loh, K.C. Biodegradation of Aromatic Compounds: Current Status and Opportunities for Biomolecular Approaches. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 85, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritash, A.K.; Kaushik, C.P. Biodegradation Aspects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, A.; Ucan-Marin, F. A Literature Review on the Aquatic Toxicology of Petroleum Oil: An Overview of Oil Properties and Effects to Aquatic Biota; Reseach Document 2015/007; DFO Canada, Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Boufadel, M.; Chen, B.; Foght, J.; Hodson, P.; Swanson, S.; Venosa, A. Expert Panel Report on the Behaviour and Environmental Impacts of Crude Oil Released into Aqueous Environments; Royal Society of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015; ISBN 978-1-928140-02-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal, D.; Ghosh, S.; Dutta, T.K.; Ahn, Y. Current State of Knowledge in Microbial Degradation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): A Review. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, M.; Suzuki, N. Toxicities of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons for Aquatic Animals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezeshki, S.R.; Hester, M.W.; Lin, Q.; Nyman, J.A. The Effects of Oil Spill and Clean-up on Dominant US Gulf Coast Marsh Macrophytes: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2000, 108, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, R.Z. Responding To Oil Spills in Coastal Marshes: The Fine Line Between Help and Hindrance. HAZMAT Report 96-2; Hazardous Materirals Response and Assessments Division, NOAA: Seattle, WA, USA, 1995; Volume 96. [Google Scholar]

- Etkin, D.S.; Tebeau, P. Assessing Progress and Benefits of Oil Spill Response Technology Development since Exxon Valdez. Int. Oil Spill Conf. 2003, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Das, N.; Chandran, P. Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon Contaminants: An Overview. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 941810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, M.J.; Peters, L.; Guttormson, A.; Tremblay, J.; Wasserscheid, J.; Timlick, L.; Greer, C.W.; Rodríguez Gil, J.L.; Halldorson, T.; Havens, S.; et al. Assessing Changes to the Root Biofilm Microbial Community on an Engineered Floating Wetland upon Exposure to a Controlled Diluted Bitumen Spill. Front. Synth. Biol. 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M. Engineered Floating Wetlands as a Secondary Oil Spill Remediation Strategy for Freshwater Shorelines. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2024. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1993/38302 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Rehman, K.; Imran, A.; Amin, I.; Afzal, M. Inoculation with Bacteria in Floating Treatment Wetlands Positively Modulates the Phytoremediation of Oil Field Wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 349, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, M.N.; Scalvenzi, L. Petroleum Degradation: Promising Biotechnological Tools for Bioremediation. In Recent Insights in Petroleum Science and Engineering; Zoveidavianpoor, M., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2018; pp. 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilon-Smits, E. Phytoremedation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Bano, A. Rhizoremediation of Petroleum Hydrocarbon, Prospects and Future. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 108347–108361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, S.; Pandey, P.; Bhargava, B.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, V.; Krishan, D. Bioremediation of Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Using Rhizosphere Technology. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2015, 46, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, B. Phytoremediation: Role of Aquatic Plants in Environmental Clean-Up; Springer India: Delhi, India, 2013; ISBN 9788132213079. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, B.C.; George, S.J.; Price, C.A.; Ryan, M.H.; Tibbett, M. The Role of Root Exuded Low Molecular Weight Organic Anions in Facilitating Petroleum Hydrocarbon Degradation: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 472, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muratova, A.; Golubev, S.; Wittenmayer, L.; Dmitrieva, T.; Bondarenkova, A.; Hirche, F.; Merbach, W.; Turkovskaya, O. Effect of the Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Phenanthrene on Root Exudation of Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 66, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chi, J. Phytoremediation of Sediments Polluted with Phenanthrene and Pyrene by Four Submerged Aquatic Plants. J. Soils Sediments 2016, 16, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macek, T.; Makova, M.; Kas, J. Exploitation of Plants for the Removal of Organics in Environmental Remediation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2000, 18, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Z. Phenanthrene-Degrading Bacteria on Root Surfaces: A Natural Defense That Protects Plants from Phenanthrene Contamination. Plant Soil 2018, 425, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubev, S.N.; Schelud’Ko, A.V.; Muratova, A.Y.; Makarov, O.E.; Turkovskaya, O.V. Assessing the Potential of Rhizobacteria to Survive under Phenanthrene Pollution. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2009, 198, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Rehman, K.; Shabir, G.; Tahseen, R.; Ijaz, A.; Hashmat, A.J.; Brix, H. Large-Scale Remediation of Oil-Contaminated Water Using Floating Treatment Wetlands. npj Clean Water 2019, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.; Tahseen, R.; Arslan, M.; Iqbal, S.; Afzal, M. Removal of Hexadecane by Hydroponic Root Mats in Partnership with Alkane-Degrading Bacteria: Bacterial Augmentation Enhances System’s Performance. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 4611–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, K.; Arslan, M.; Müller, J.A.; Saeed, M.; Imran, A.; Amin, I.; Mustafa, T.; Iqbal, S.; Afzal, M. Bioaugmentation-Enhanced Remediation of Crude Oil Polluted Water in Pilot-Scale Floating Treatment Wetlands. Water 2021, 13, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.; Palace, V.; Grosshans, R.; Levin, D.B. Floating Treatment Wetlands for the Bioremediation of Oil Spills: A Review. J. Environ. Manage. 2022, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency Priority Pollutant List. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-09/documents/priority-pollutant-list-epa.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Canadian Water Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Aquatic Life—Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs). In Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines; Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1999; Available online: http://ceqg-rcqe.ccme.ca/download/en/243 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Waigi, M.G.; Kang, F.; Goikavi, C.; Ling, W.; Gao, Y. Phenanthrene Biodegradation by Sphingomonads and Its Application in the Contaminated Soils and Sediments: A Review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2015, 104, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanovich, S.; Yang, Z.; Hanson, M.; Hollebone, B.P.; Orihel, D.M.; Palace, V.; Rodriguez-Gil, J.R.; Mirnaghi, F.; Shah, K.; Blais, J.M. Fate of Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds from Diluted Bitumen Spilled into Freshwater Limnocorrals. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 819, 151993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyama, T.; Yu, N.; Kumada, H.; Sei, K.; Ike, M.; Fujita, M. Accelerated Aromatic Compounds Degradation in Aquatic Environment by Use of Interaction between Spirodela Polyrrhiza and Bacteria in Its Rhizosphere. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2006, 101, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machate, T.; Noll, H.; Behrens, H.; Kettrup, A. Degradation of Phenanthrene and Hydraulic Characteristics in a Constructed Wetland. Water Res. 1997, 31, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kösesakal, T.; Seyhan, M. Phenanthrene Stress Response and Phytoremediation Potential of Free-Floating Fern Azolla Filiculoides Lam. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2023, 25, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The Water-Culture Method for Growing Plants without Soil; University of California, College of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Canadian Water Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Aquatic Life—Phosphorus: Canadian Guidance Framework for the Management of Freshwater Systems. In Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines; Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2004; Available online: https://ccme.ca/en/res/phosphorus-en-canadian-water-quality-guidelines-for-the-protection-of-aquatic-life.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Naczi, R.F.C. Systematics of Carex Section Griseae (Cyperaceae). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Starr, J.R.; Naczi, R.F.C.; Chouinard, B.N. Plant DNA Barcodes and Species Resolution in Sedges (Carex, Cyperaceae). Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, E.; Zarfl, C. Sorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) to Low and High Density Polyethylene (PE). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 1296–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, B.J.; Duxbury, C.L.; Dixon, D.G.; Greenberg, B.M. Toxicity of a PAH Photooxidation Product to the Bacteria Photobacterium Phosphoreum and the Duckweed Lemna Gibba: Effects of Phenanthrene and Its Primary Photoproduct, Phenanthrenequinone. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1997, 16, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, I.; Francisco, O.; Thomas, P.J.; Johnson, W.; Marvin, C.; Stetefeld, J.; Tomy, G.T. Validation of a Simultaneous Method for Determining Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds and Alkylated Isomers in Biota. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 32, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heumann, K.G. Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry of Inorganic and Organic Substances. Fresenius’ Zeitschrift Anal. Chem. 1986, 325, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heumann, K.G. Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process. 1992, 118–119, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LuminUltra 2nd Generation ATP® Testing. Available online: https://www.luminultra.com/tech/2nd-generation-atp/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw0bunBhD9ARIsAAZl0E1KvVsKRkEIWCdNv1ciTaXT-WYeXv8-_2tMGRwgOSqEIh69sTctNScaAhicEALw_wcB (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- LuminUltra. Product Instructions. PhotonMasterTM Luminometer & Bluetooth® Module; LuminUltra: Fredericton, NB, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- LuminUltra. Test Kit Instructions—Deposit and Surface Analysis (DSA); LuminUltra: Fredericton, NB, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, D.; Doll, J.; Wheeler, A.; Dinno, A. _FSA: Simple Fisheries Stock Assessment Methods_. R Package Version 0.9.4, 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=FSA (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Pedersen, E.; Simpson, G.; Ross, N.; Rodriguez-Sanchez, F. Hierarchical Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with Mgcv. Available online: https://github.com/eric-pedersen/mixed-effect-gams (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Pedersen, E.J.; Miller, D.L.; Simpson, G.L.; Ross, N. Hierarchical Generalized Additive Models in Ecology: An Introduction with Mgcv. PeerJ 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781315370279. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S. Mgcv Pacakge. Mixed GAM Compution Vehicle with GCV/AIC/REML/NCV Smoothness Estimation and GAMMS by REML/PQL. Version 1.9-0. 2023. Available online: https://cran.rstudio.com/web/packages/mgcv/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wood, S.N. Stable and Efficient Multiple Smoothing Parameter Estimation for Generalized Additive Models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004, 99, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Thin Plate Regression Splines. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2003, 65, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Fast Stable Restricted Maximum Likelihood and Marginal Likelihood Estimation of Semiparametric Generalized Linear Models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2011, 73, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Spring-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D.; R Core Team. _nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models_. R Package Version 3.1-160. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=nlme (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS; Springer-Verlag: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-387-98957-9. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency Degradation Kinetics Equations. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-science-and-assessing-pesticide-risks/degradation-kinetics-equations (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Guidance to Calculate Representative Half-Life Values and Characterizing Pesticide Degradation. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-science-and-assessing-pesticide-risks/guidance-calculate-representative-half-life-values (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Paine, C.E.T.; Marthews, T.R.; Vogt, D.R.; Purves, D.; Rees, M.; Hector, A.; Turnbull, L.A. How to Fit Nonlinear Plant Growth Models and Calculate Growth Rates: An Update for Ecologists. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez, F. _nlraa: Nonlinear Regression for Agricultural Applications_. R Package Version 1.9.3. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=nlraa (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Vandermeer, J. How Populations Grow: The Exponential and Logistic Equations. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2010, 3, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, M.J.; Guttormson, A.; Peters, L.; Halldorson, T.; Tomy, G.; Rodríguez Gil, J.L.; Cooney, B.; Grosshans, R.; Levin, D.B.; Palace, V.P. Data Associated with a Study on Freshwater Phenanthrene Removal by Three Emergent Wetland Plants Conducted in a Microcosm Experiment at the IISD Experimental Lakes Area, ON, Canada, in 2022; Ver 1; Environmental Data Inititiave: Madison, WI, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawash, A.B.; Dragh, M.A.; Li, S.; Alhujaily, A.; Abbood, H.A.; Zhang, X.; Ma, F. Principles of Microbial Degradation of Petroleum Hydrocarbons in the Environment. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2018, 44, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.A.; Muhlfeld, C.C.; Hauer, F.R. Temperature. In Methods in Stream Ecology: Volume 1: Ecosystem Structure, 3rd ed.; Hauer, F.R., Lamberti, G.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 109–120. ISBN 9780124165588. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, J.; Ashton, C.; Geary, L. The Effects of Temperature on pH Measurement; Technical Services Department, Reagecon Diagnostics Ltd.: County Clare, Ireland, 2005; Volume TSP-01. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment. Canadian Water Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Aquatic Life—Dissolved Oxygen (Freshwater). In Canadian Environmental Quality Guidelines; Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1999; Available online: https://ccme.ca/en/res/dissolved-oxygen-freshwater-en-canadian-water-quality-guidelines-for-the-protection-of-aquatic-life.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Pokorný, J.; Květ, J. Aquatic Plants and Lake Ecosystems. In The Lakes Handbook; O’Sullivan, P.E., Reynolds, C.S., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 309–340. ISBN 0-632-04797-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, W.K. Freshwater Ecology: Concepts and Environmental Applications; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hinsinger, P.; Plassard, C.; Tang, C.; Jaillard, B. Origins of Root-Mediated PH Changes in the Rhizosphere and Their Responses to Environmental Constraints: A Review. Plant Soil 2003, 248, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stottmeister, U.; Wießner, A.; Kuschk, P.; Kappelmeyer, U.; Kästner, M.; Bederski, O.; Müller, R.A.; Moormann, H. Effects of Plants and Microorganisms in Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment. Biotechnol. Adv. 2003, 22, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharey, G.S.; Palace, V.; Whyte, L.; Greer, C.W. Native Freshwater Lake Microbial Community Response to an in Situ Experimental Dilbit Spill. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2024, 100, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharey, G.S.; Palace, V.; Whyte, L.; Greer, C.W. Influence of Heavy Canadian Crude Oil on Pristine Freshwater Boreal Lake Ecosystems in an Experimental Oil Spill. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2024, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieβner, A.; Kuschk, P.; Stottmeister, U. Oxygen Release by Roots of Typha Latifolia and Juncus Effusus in Laboratory Hydroponic Systems. Acta Biotechnol. 2002, 22, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randerson, P.F.; Moran, C.; Bialowiec, A. Oxygen Transfer Capacity of Willow (Salix viminalis L.). Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2306–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhead, K.K.; Reddy, K.R. Oxygen Transport through Selected Aquatic Macrophytes. J. Environ. Qual. 1988, 17, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Posch, T.; Schmidt, T. Sorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) on Glass Surfaces. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flocco, C.G.; Lobalbo, A.; Carranza, M.P.; Bassi, M.; Giulietti, A.M.; Cormack, W. Mac Some Physiological, Microbial, and Toxicological Aspects of the Removal of Phenanthrene by Hydroponic Cultures of Alfalfa (Medicago Sativa L.). Int. J. Phytoremediation 2002, 4, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, S.; Karlson, U. Aspects of Phytoremediation of Organic Pollutants. J. Soils Sediments 2001, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information PubChem Compound Summary for Phenanthrene. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Phenanthrene (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Jatav, K.; Singh, R.P. Phytoremediation Using Algae and Macrophytes: II. In Phytoremediation: Management of Environmental Contaminants; Ansari, A.A., Gill, S.S., Gill, R., Lanza, G.R., Newman, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 291–296. ISBN 9783319109688. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Liu, J.; Gao, Y.; Jin, L.; Gu, Y.; Wang, W. Isolation, Plant Colonization Potential, and Phenanthrene Degradation Performance of the Endophytic Bacterium Pseudomonas Sp. Ph6-Gfp. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, X. Characterization of Biofilm Formed by Phenanthrene-Degrading Bacteria on Rice Root Surfaces for Reduction of Pah Contamination in Rice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Hernández, V.; Ventura-Canseco, L.M.C.; Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.A.; Pérez-Hernández, I.; Hernández-Guzmán, M.; Enciso-Sáenz, S. The Potential of Mimosa Pigra to Restore Contaminated Soil with Anthracene and Phenanthrene. Terra Latinoam. 2020, 38, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ma, Z.; Li, S.; Waigi, M.G.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J.; Ling, W. Colonization of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon-Degrading Bacteria on Roots Reduces the Risk of PAH Contamination in Vegetables. Environ. Int. 2019, 132, 105081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia-hua, L.; Hong-yan, G.; Xiao-rong, W.; Hong, W.M.; ShiHe, W.; Da-qiang, Y.; Ying, Y.; Jingfei, Z. Plant-Promoted Dissipation of Four Submerged Macrophytes to Phenanthrene. Aquat. Ecosyst. Heal. Manag. 2009, 12, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazouli, M.A.; Ala, A.; Asghari, S.; Babanezhad, E. Evaluation of Azolla Filiculoides Potential in Pyrene and Phenanthrene Accumulation and Phytoremediation in Contaminated Waters. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazouli, M.A.; Asghari, S.; Tarrahi, R.; Lisar, S.Y.S.; Babanezhad, E.; Dashtban, N. The Potential of Common Duckweed (Lemna Minor) in Phytoremediation of Phenanthrene and Pyrene. Environ. Eng. Res. 2022, 28, 210592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.A.; Greer, C.W.; Farrell, R.E.; Germida, J.J. Plant Root Exudates Impact the Hydrocarbon Degradation Potential of a Weathered-Hydrocarbon Contaminated Soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 52, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louvel, B.; Cébron, A.; Leyval, C. Root Exudates Affect Phenanthrene Biodegradation, Bacterial Community and Functional Gene Expression in Sand Microcosms. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2011, 65, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.M.; Heise, S.; Ahlf, W. Effects of Phenanthrene on Lemna Minor in a Sediment-Water System and the Impacts of UVB. Ecotoxicology 2002, 11, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalkowsky, S.H.; He, Y.; Jain, P. Handbook of Aqueous Solubility Data, 2nd ed.; CRC Press LLC.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4398-0246-5. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, F.P. Determination of Temperature Dependence of Solubilities of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Aqueous Solutions by a Fluorescence Method. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1977, 22, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Gil, J.L.; Stoyanovich, S.; Hanson, M.L.; Hollebone, B.; Orihel, D.M.; Palace, V.; Faragher, R.; Mirnaghi, F.S.; Shah, K.; Yang, Z.; et al. Simulating Diluted Bitumen Spills in Boreal Lake Limnocorrals - Part 1: Experimental Design and Responses of Hydrocarbons, Metals, and Water Quality Parameters. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 790, 148537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammarco, P.W.; Kolian, S.R.; Warby, R.A.F.; Bouldin, J.L.; Subra, W.A.; Porter, S.A. Distribution and Concentrations of Petroleum Hydrocarbons Associated with the BP/Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 73, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.; Hayes, A.; Couch, S. _broom: Convert Statistical Objects in Tidy Tibbles_. R Package Version 1.0.3. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=broom (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. _dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation_. R Package Version 1.1.0. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dplyr/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Kassambara, A. _ggpubr: “ggplot2” Based Publication Ready Plots_. R Package Version 0.6.0. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=ggpubr (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Simpson, G. _gratia: Graceful Ggplot-Based Graphics and Other Functions for GAMs Fitted Using Mgcv_. R Package Version 0.8.1. 2023. Available online: https://gavinsimpson.github.io/gratia/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Müller, K. _here: A Simpler Way to Find Your Files_. R Package 1.0.1. 2020. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/here/index.html (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Firke, S. _janitor: Simple Tools for Examining and Cleaning Dirty Data_. R Package Version 2.2.0. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=janitor (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Grolemund, G.; Wickham, H. Dates and Time Made Easy with Lubridate. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 40, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, S.; Piepho, H.; Dorai-Raj, S. _multcompView: Visualization of Paired Comparisons_. R Package Version 0.1-8. 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=multcompView (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Pedersen, T. _patchwork: The Composer of Plots_. R Package Version 1.1.2. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=patchwork (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Henry, L. _purrr: Functional Programming Tools_. R Package Version 1.0.1. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=purrr (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Mangiafico, S. _rcompanion: Functions to Support Extension Education Program Evaluation_. R Package Version 2.4.21. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=rcompanion (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Hester, J.; Bryan, J. _readr: Read Rectangular Text Data_. R Package Version 2.1.4. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=readr (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wickham, H. _stringr: Simple, Consitent Wrappers for Common String Operations_. R Package Version 1.5.0. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=stringr (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Müller, K.; Wickham, H. _tibble: Simple Data Frames_.R Package Version 3.1.8. 2022. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=tibble (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Vaughan, D.; Girlich, M. _tidyr: Tidy Messy Data_. R Package Version 1.3.0. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=tidyr (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Zuur, A.F.; Ieno, E.N.; Walker, N.J.; Saveliev, A.A.; Smith, G.M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R; Gail, M., Krickeberg, K., Samet, J.M., Tsiatis, A., Wong, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780429576966. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | y0 (mg/L) | k | DT50 (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenanthrene | 1.29 (1.01–1.58) | 0.0058 (0.0027–0.0089) | 120 (78–259) |

| Phenanthrene + Cattail | 0.67 (0.57–0.77) | 0.0125 (0.0085–0.0165) | 55 (42–82) |

| Phenanthrene + Sedge A | 0.53 (0.44–0.61) | 0.0089 (0.0058–0.0120) | 78 (58–120) |

| Phenanthrene + Sedge B | 0.76 (0.63–0.88) | 0.0055 (0.0032–0.0077) | 127 (90–213) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanley, M.J.; Guttormson, A.; Peters, L.E.; Halldorson, T.; Tomy, G.; Rodríguez Gil, J.L.; Cooney, B.; Grosshans, R.; Levin, D.B.; Palace, V.P. Freshwater Phenanthrene Removal by Three Emergent Wetland Plants. Water 2025, 17, 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223327

Stanley MJ, Guttormson A, Peters LE, Halldorson T, Tomy G, Rodríguez Gil JL, Cooney B, Grosshans R, Levin DB, Palace VP. Freshwater Phenanthrene Removal by Three Emergent Wetland Plants. Water. 2025; 17(22):3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223327

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanley, Madeline J., Aidan Guttormson, Lisa E. Peters, Thor Halldorson, Gregg Tomy, José Luis Rodríguez Gil, Blake Cooney, Richard Grosshans, David B. Levin, and Vince P. Palace. 2025. "Freshwater Phenanthrene Removal by Three Emergent Wetland Plants" Water 17, no. 22: 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223327

APA StyleStanley, M. J., Guttormson, A., Peters, L. E., Halldorson, T., Tomy, G., Rodríguez Gil, J. L., Cooney, B., Grosshans, R., Levin, D. B., & Palace, V. P. (2025). Freshwater Phenanthrene Removal by Three Emergent Wetland Plants. Water, 17(22), 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223327