Empowering Sustainability Through AI-Driven Monitoring: The DEEP-PLAST Approach to Marine Plastic Detection and Trajectory Prediction for the Black Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Remote Sensing of Marine Litter

2.2. Deep Learning for Plastic Detection

2.3. Benchmark Datasets

| Dataset/Project | Sensor & Resolution | Labels & Classes | Size/Scope | Geography/Coverage | Access/License | Notes/Typical Use | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARIDA (Marine Debris Archive) | Sentinel-2 MSI (10–20 m) | Pixel/patch labels; 14 classes (marine litter, natural organic material, algae, ships, waves, water types, etc.) | 1381 annotated patches (polygons) | Global hotspots (multi-season) | Open (PLOS ONE + Zenodo) | Principal benchmark for pixel-level S2 segmentation; curated around verified debris events; strong negatives for confounders | [12] |

| Floating Objects (ESA φ-lab) | Sentinel-2 MSI (10–20 m) | Patch-level labels of floating object categories; baselines provided | Large-scale (thousands of patches) | Global oceans & lakes | Open (ISPRS Annals) | Focus on “big patches” of floating objects; useful for training & failure analysis across diverse waters | [13] |

| Plastic Litter Project (Controlled targets) | Sentinel-2 MSI + UAV (cm-level) | Known plastic targets (10 × 10 m), spectral/measured GT | Dozens of scenes; multiple target configs | Coastal test sites (Mediterranean) | Open (paper + Zenodo) | Quantifies biofouling/submergence effects; suggests S2 detectability when >~20% pixel coverage | [5] |

| NASA IMPACT Marine Debris (PlanetScope) | PlanetScope (3 m, RGB + NIR) | Object-level polygons; detection benchmarks | 1370 labeled polygons; 256 × 256 tiles | Honduras, Greece, Ghana (event-based) | Open (NASA Earthdata) | Enables object detection of smaller aggregations than S2; limited spectral range vs. S2 | [14] |

| UAV Beach/Coastal Litter (Gonçalves et al.) | UAV RGB (cm-level) | Object-oriented labels of macro-litter on beaches | Multiple UAV flights/mosaics | Sandy beaches (Portugal) | [22] |

2.4. Challenges

- One major difficulty is spectral confusion between plastic debris and other floating materials. Plastics, especially weathered items, can exhibit reflectance spectra similar to natural organics or algae. For example, large blooms of Sargassum algae or rafts of sea foam can produce signals that mimic those of plastic, leading to false positives [23]. Conversely, certain plastics that have been in the water for long periods accumulate biofouling (algal growth) which changes their optical properties, making them less reflective in visible wavelengths and more similar to natural debris [23]. The study also notes that biofouling primarily dampens the plastic signal in RGB bands, while partial submergence of plastics reduces reflectance across all Sentinel-2 bands (especially in NIR), further complicating detection. This means algorithms must distinguish plastics not just by raw reflectance, but by subtle anomalies or context.

- Another challenge is the spatial resolution limit of satellites [23]. Sentinel-2′s 10 m pixels can only detect relatively large accumulations of debris—typically on the order of tens of square meters. If plastics are scattered or sparse (covering <20% of a pixel), they may go undetected. Higher-resolution commercial satellites (e.g., WorldView at ~0.3 m or PlanetScope at 3 m) can see smaller objects, but often lack the spectral bands (e.g., shortwave IR) that highlight plastics, and are not freely available for continuous monitoring. There is thus an inherent trade-off between spatial and spectral resolution in satellite-based plastic monitoring [18].

- Ground truth annotation quality is another bottleneck. Validating that an observed anomaly is truly plastic requires either in situ confirmation or reliable indirect evidence, which is seldom available at scale. Many datasets rely on visual interpretation of satellite images or reports of known pollution events to label plastics [12]. This can introduce label noise—some purported “plastic” pixels might actually be other debris or vegetation (and vice versa). The MARIDA dataset attempted to mitigate this by focusing on confirmed marine litter events and providing multi-class labels (allowing models to learn distinctions). Nonetheless, the scarcity of labeled examples of floating plastic (relative to the vast area of oceans) means models face a highly imbalanced classification problem. Plastics are the proverbial “needle in a haystack”, as noted by NASA’s IMPACT team [14]. Techniques like data augmentation, semi-supervised learning, and transfer learning from related domains are being explored to address the paucity of training data. Additionally, environmental factors such as glint from sunglint on waves, turbid water (sediment or plankton bloom), and cloud shadows can all mask or mimic the spectral signals used to detect plastics [8]. These factors demand robust preprocessing, such as sunglint correction and cloud masking, as well as algorithms that are resilient to noise.

3. Methodology

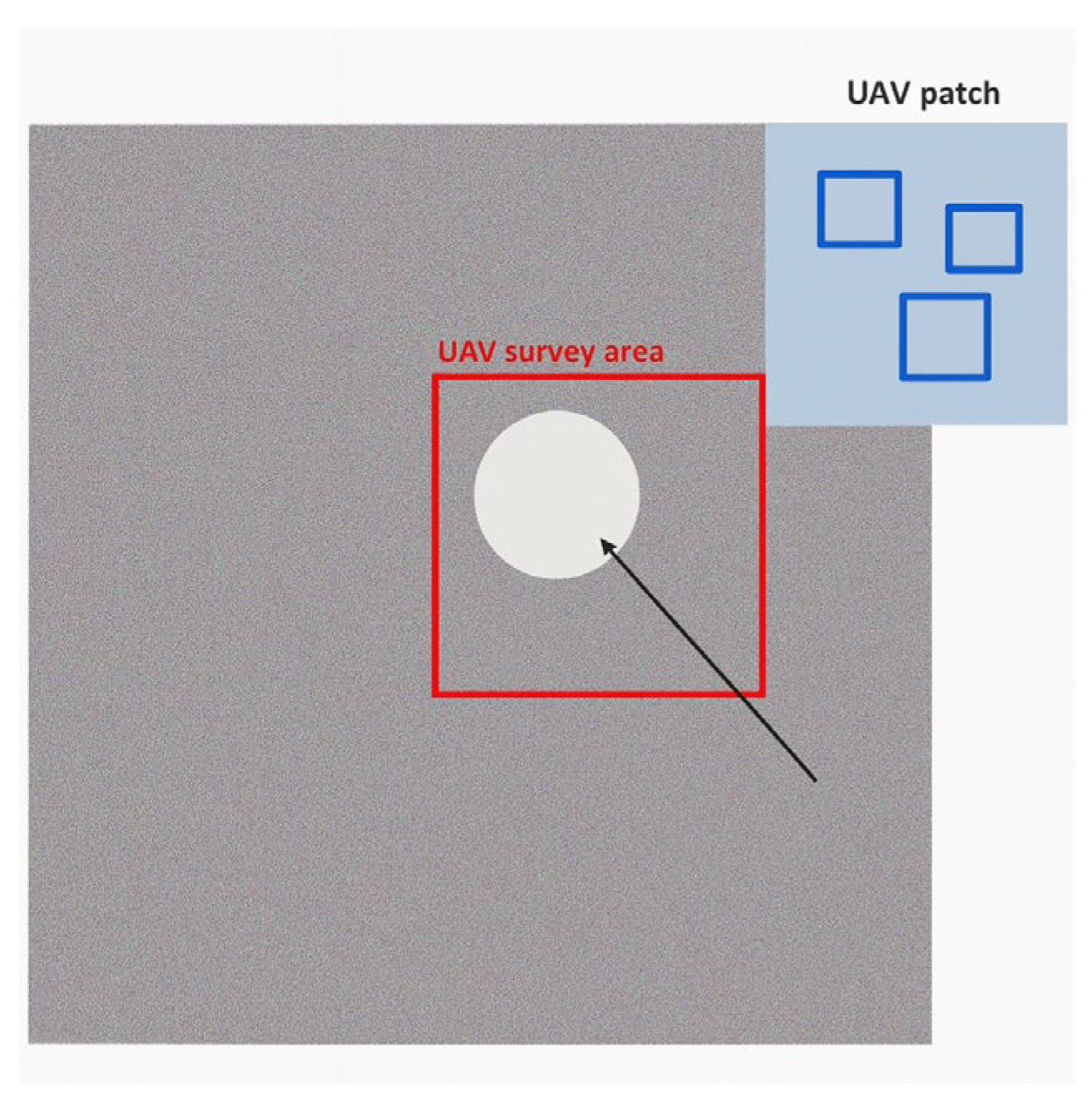

3.1. Data Acquisition and Study Are

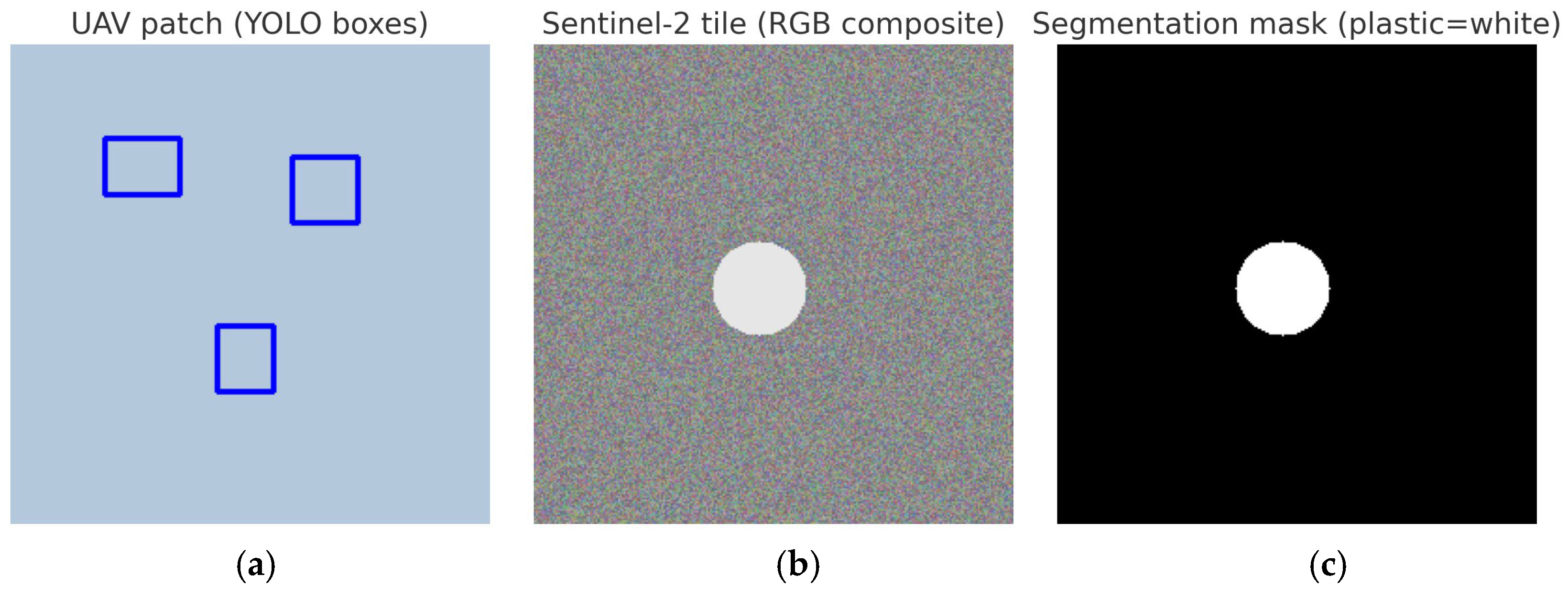

3.2. Dataset Splitting and Annotation

3.3. Data Preprocessing

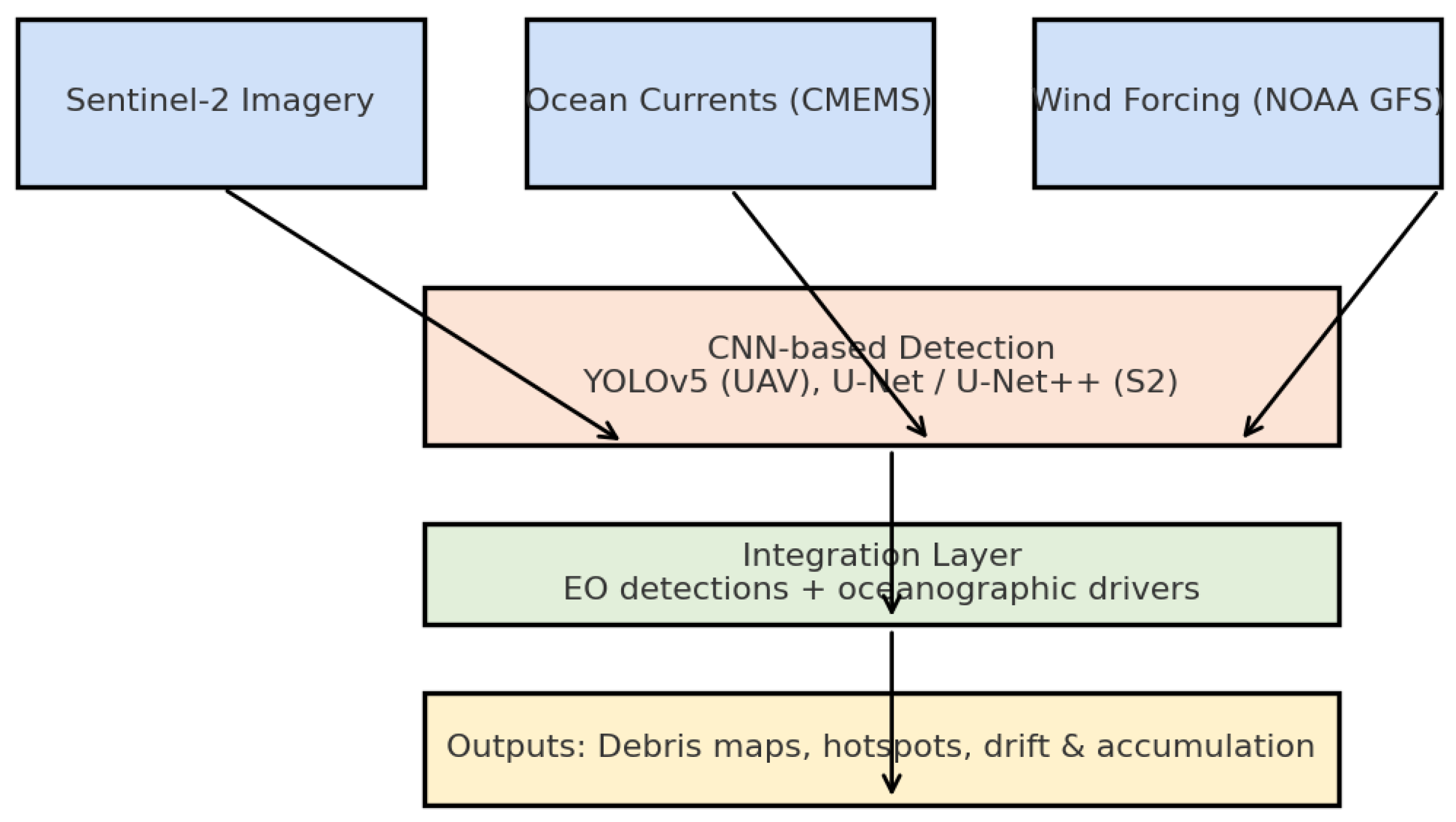

3.4. Model Training Details

- (1)

- We fine-tuned a YOLOv5s model on our UAV imagery. Training was performed on 1280 × 1280 px image patches (to exploit the high UAV resolution) for 100 epochs. We initialized the model with COCO-pretrained weights for transfer learning, which improved convergence given our relatively limited dataset. A batch size of 16 and a cosine learning rate schedule were used to ensure stable convergence. We also employed mosaic augmentation and random geometric transformations during training, which have been shown to make YOLO more robust to varied UAV flight angles and altitudes [29]. Early stopping was applied with patience 10—if the validation loss did not improve for 10 epochs, training was halted to prevent overfitting.

- (2)

- For the semantic segmentation of plastics in Sentinel-2 imagery, we trained two architectures (U-Net and U-Net++ [30,31]) using 512 × 512 px image chips. Both networks were initialized with ImageNet-pretrained encoders to accelerate learning. We used the Adam optimizer (initial learning rate, e.g., 1 × 10−3) with a polynomial learning rate decay schedule [22]. To address the strong class imbalance (plastic pixels constitute < 1% of all pixels), we used a combined Binary Cross-Entropy + Dice loss [30], which balances pixel accuracy with overlap of the plastic class. Data augmentation was applied to each training batch to improve generalization across different water colors and conditions. Early stopping was used, given the limited training data, to avoid overfitting. U-Net++ required slightly more epochs (~50) to converge than U-Net (~40 epochs) due to its additional decoder layers.

3.5. Validation Metrics and Evaluation Protocol

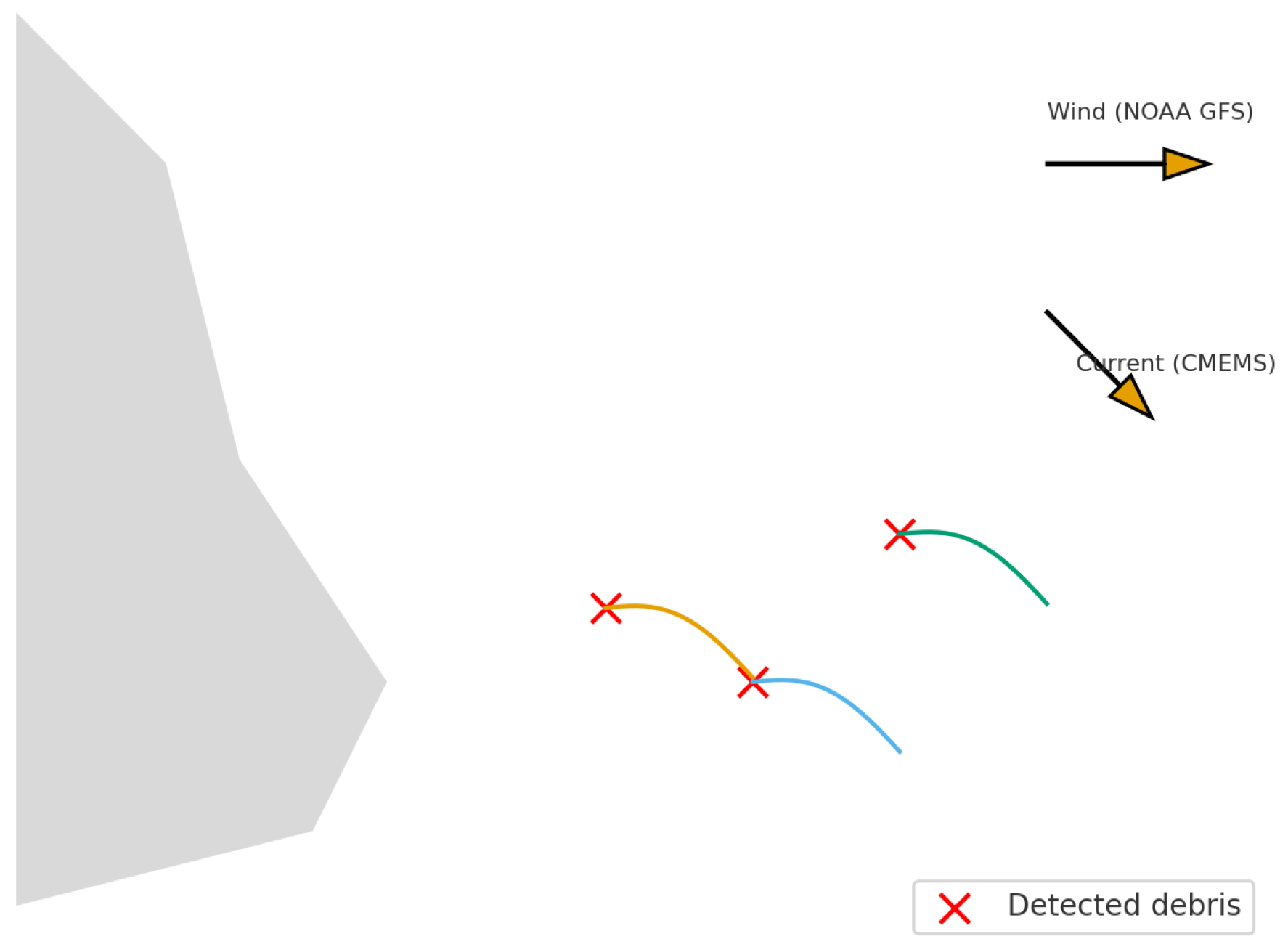

3.6. Trajectory Prediction Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

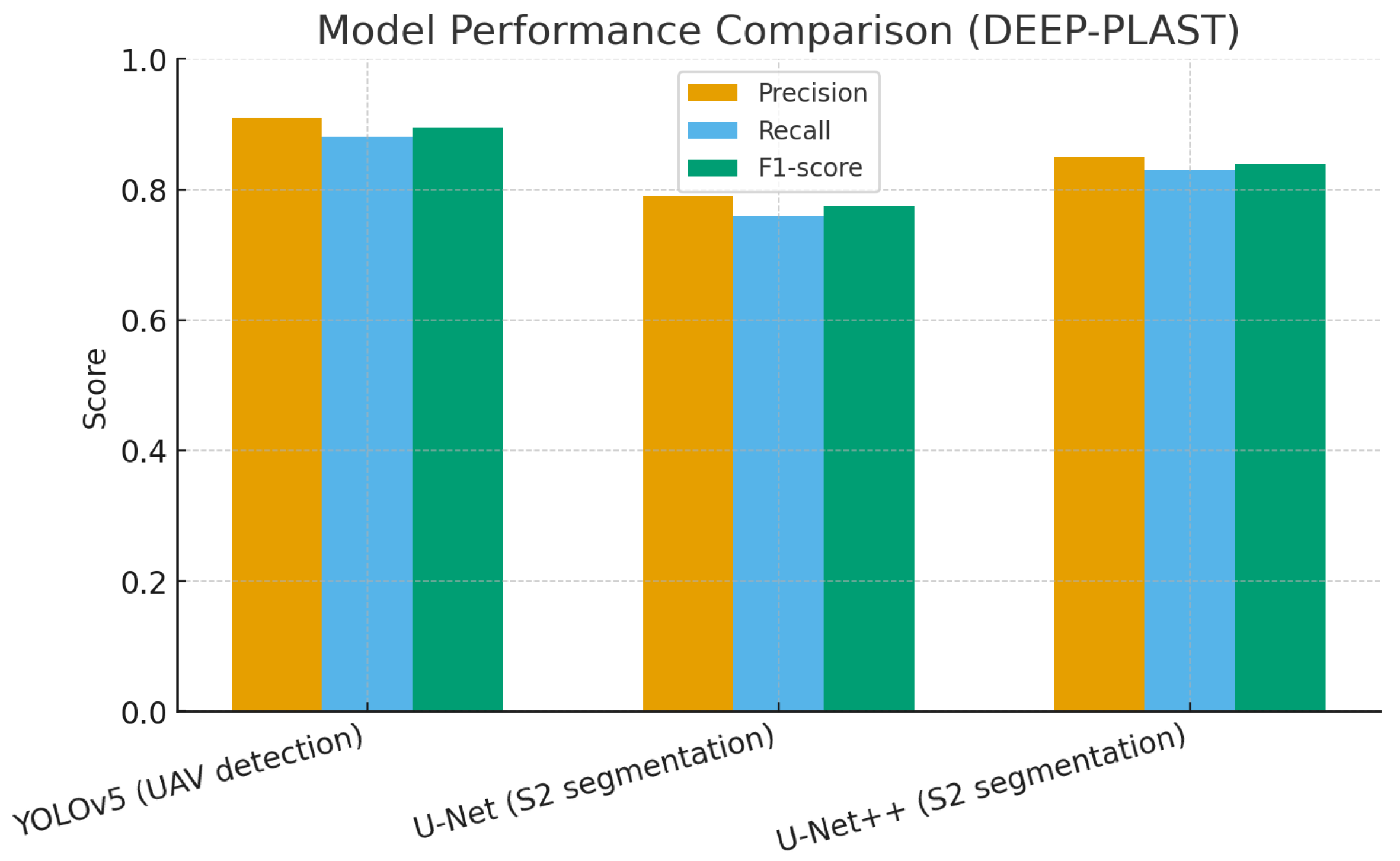

4.1. Detection and Segmentation Performance

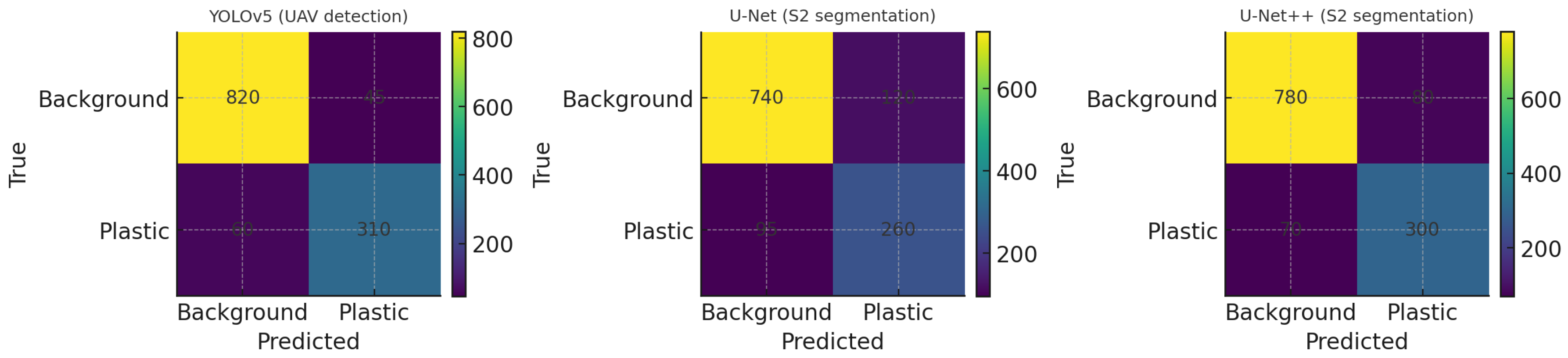

4.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis

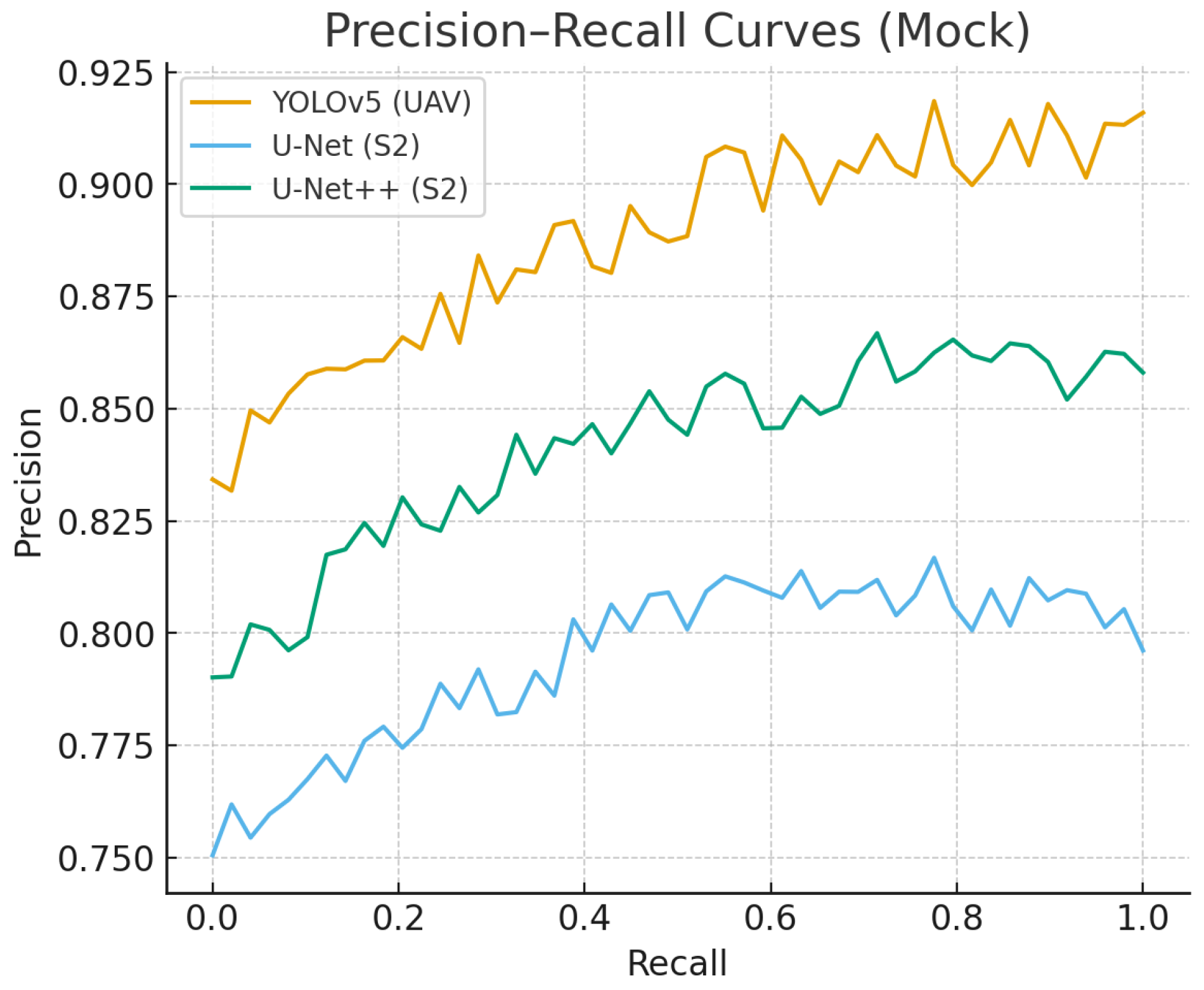

4.3. Precision–Recall Behavior

4.4. Implications for the Black Sea

4.5. Limitations and Future Work

- Spatial resolution limitations. Sentinel-2 imagery, with its 10 m ground sampling distance for key bands (B2, B3, B4, B8), imposes a practical detection threshold: debris must occupy a significant fraction of a pixel to be reliably segmented. Empirical observations and UAV cross-validation suggest that plastic items occupying less than ~20% of a pixel are often missed or misclassified, especially under variable illumination.

- Ground truth scarcity and label uncertainty. Robust supervised learning depends on high-quality labeled data. However, annotating marine plastics in EO imagery is inherently challenging due to cloud cover, sunglint, water turbidity, and lack of direct field validation. Although we used UAV imagery and manual verification to guide annotation, label noise remains a concern, particularly for ambiguous pixels at the edge of debris patches. Moreover, the current validation of drift simulations remains primarily qualitative, due to limited availability of in situ trajectory data and ground-truth observations.

- Environmental factors. Despite rigorous preprocessing, certain phenomena such as floating algal blooms or sea foam can still mimic the spectral and spatial patterns of plastic, which contributes to false positives.

- Model scalability. While U-Net++ performed well on the Black Sea dataset, its transferability to other marine environments remains untested. Although the DEEP-PLAST framework is designed to be transferable to other semi-enclosed marine basins such as the Mediterranean or Baltic Seas, successful adaptation requires addressing region-specific challenges, including variations in turbidity, atmospheric conditions, and cloud cover, which can affect detection accuracy. Additionally, differences in the spectral properties of local plastic waste and the availability of labeled training data may impact model scalability.

- Multi-sensor data fusion: Combining Sentinel-2 with higher-resolution sensors will improve detection reliability and cross-validate scenes. Moreover, performing a full seasonal analysis will add new insights into the impact of seasonality and atmospheric conditions on floating plastic accumulations.

- Semi-supervised learning: Techniques such as pseudo-labeling, consistency regularization, and teacher–student networks can leverage unlabeled or partially labeled data to improve generalization while reducing annotation costs.

- Drift model validation: Integrating GPS-tagged marine litter or deploying low-cost drifters during detection campaigns will enable quantitative validation of transport models, a key step for policy applications.

- Operational integration: Building a web-based dashboard to visualize detections, forecasts, and drift trajectories will make outputs accessible to stakeholders such as NGOs and regional authorities.

- Coastal collaboration: Partnering with local cleanup initiatives will provide field validation, test usability of predictions in real-world operations, and foster feedback loops that improve both scientific and societal relevance.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| F1-score | Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| RGB | Red-Green-Blue (image channels) |

| S2/Sentinel-2 | European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 Satellite |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index |

| QA60 | Quality Assessment Band 60 (Sentinel-2 cloud mask) |

| SCL | Scene Classification Layer (Sentinel-2 auxiliary product) |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| ES | Early Stopping |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| MSFD | Marine Strategy Framework Directive |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| MPA | Marine Protected Area |

| ASV | Autonomous Surface Vehicle |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| Copernicus | EU Earth observation program (includes Sentinel satellites) |

| L2A | Level-2A Processing (surface reflectance products from Sentinel-2) |

| FDI | Floating Debris Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| MARIDA | Marine Debris Archive (open EO benchmark dataset) |

| DETR | DEtection TRansformer (vision transformer model for object detection) |

References

- Biermann, L.; Clewley, D.; Martinez-Vicente, V.; Topouzelis, K. Finding Plastic Patches in Coastal Waters Using Optical Satellite Data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, S.; Sannigrahi, S.; Bhatt, S.; Zhang, Q.; Basu, A. Using Sentinel-2 Data and Machine Learning to Detect Floating Plastic Debris. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannigrahi, S.; Basu, B.; Basu, A.S.; Pilla, F. Development of automated marine floating plastic detection system using Sentinel-2 imagery and machine learning models. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 178, 113527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.; Azevedo, J. Automatic Identification of Floating Marine Debris Using Sentinel-2 and Gradient-Boosted Trees. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, D.; Topouzelis, K.; Suaria, G.; Aliani, S.; Corradi, P. Sentinel-2 Detection of Floating Marine Litter Targets with Partial Spectral Unmixing and Spectral Comparison with Other Floating Materials (Plastic Litter Project 2021). Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Kapelan, Z.; De Vries, R.; Vriend, P.; Peereboom, E.C.; Okkerman, I.; Taormina, R. Deep learning for detecting macroplastic litter in water bodies: A review. Water Res. 2023, 231, 119632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11045, pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Booth, H.; Ma, W.; Karakuş, O. High-precision density mapping of marine debris and floating plastics via satellite imagery. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Vicente, V.; Clark, J.; Corradi, P.; Aliani, S.; Arias, M.; Bochow, M.; Bonnery, G.; Cole, M.; Cózar, A.; Donnelly, R.; et al. Measuring Marine Plastic Debris from Space: Requirements and Approaches. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Houlsby, N. An Image Is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Vienna, Austria, 4 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, L.M.; Sagar, A.S.; Bui, N.D.; Nguyen, L.V.; Nguyen, T.H. Attention-guided marine debris detection with an enhanced transformer framework using drone imagery. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 197, 107089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikaki, K.; Kakogeorgiou, I.; Mikeli, P.; Raitsos, D.E.; Karantzalos, K. MARIDA: A benchmark for Marine Debris detection from Sentinel-2 remote sensing data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifdal, J.; Longépé, N.; Rußwurm, M. Towards detecting floating objects on a global scale with learned spatial features using sentinel 2. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2021, 3, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMPACT Team. Marine Debris: Finding the Plastic Needles. 2023. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/news/blog/marine-debris-finding-plastic-needles (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- IBM Space Tech. IBM PlasticNet Project. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/IBM/PlasticNet (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- van Sebille, E.; Aliani, S.; Law, K.L.; Maximenko, N.; Alsina, J.M.; Bagaev, A.; Bergmann, M.; Chapron, B.; Chubarenko, I.; Cózar, A.; et al. The Physical Oceanography of the Transport of Floating Marine Debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 023003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russwurm, M.C.; Gül, D.; Tuia, D. Improved marine debris detection in satellite imagery with an automatic refinement of coarse hand annotations. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) Workshops, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023; Available online: https://infoscience.epfl.ch/handle/20.500.14299/20581013 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Rußwurm, M.; Venkatesa, S.J.; Tuia, D. Large-scale detection of marine debris in coastal areas with Sentinel-2. iScience 2023, 26, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F. Improving YOLOv11 for marine water quality monitoring and pollution source identification. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeepLabV3. Available online: https://wiki.cloudfactory.com/docs/mp-wiki/model-architectures/deeplabv3#:~:text=DeepLabv3%2B%20is%20a%20semantic%20segmentation,module%20to%20enhance%20segmentation%20results (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Danilov, A.; Serdiukova, E. Review of Methods for Automatic Plastic Detection in Water Areas Using Satellite Images and Machine Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 5089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, G.; Andriolo, U.; Sobral, P.; Bessa, F. Quantifying Marine Macro Litter Abundance on a Sandy Beach Using Unmanned Aerial Systems and Object-Oriented Machine Learning Methods. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESA Sentinel—2 User Handbook. 2015. Available online: https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/documents/247904/685211/Sentinel-2_User_Handbook (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Codefinity. Available online: https://codefinity.com/courses/v2/ef049f7b-ce21-45be-a9f2-5103360b0655/ea906b61-a82b-47cb-9496-24e87c11b84d/36d0bcd9-218d-482a-9dbb-ee3ed1942391 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- ESA QA60/SCL Cloud and Shadow Mask Documentation, Sentinel-2 Documentation. Available online: https://documentation.dataspace.copernicus.eu/Data/SentinelMissions/Sentinel2.html (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Hedley, J.D.; Harborne, A.R.; Mumby, P.J. Technical note: Simple and robust removal of sun glint for mapping shallow-water benthos. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, D.; Topouzelis, K. Experimental observations of marginally detectable floating plastic targets in Sentinel-2 and Planet Super Dove imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 134, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics YOLOv5. 2020. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/yolov5/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U—Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. MICCAI 2015, 9351, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Marine Service (CMEMS). Global Ocean Physics Reanalysis and Forecast. 2021. Available online: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/GLOBAL_MULTIYEAR_PHY_001_030/description (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/environment/oceans-and-seas/eu-marine-strategy-framework-directive_en (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Mamaev, V.O. Black Sea Strategic Action Plan: Biological Diversity Protection. In Conservation of the Biological Diversity as a Prerequisite for Sustainable Development in the Black Sea Region; Kotlyakov, V., Uppenbrink, M., Metreveli, V., Eds.; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Year) | Model/Method | Data Source | Application Region | Reported Accuracy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biermann et al. (2020) [1] | Naïve Bayes classifier using spectral indices (FDI, NDVI) | Sentinel-2 MSI (10 m); multi-spectral pixel analysis | Coastal waters (Scotland, Canada, S. Africa, Caribbean) | ~86% accuracy in classifying plastic vs. natural debrisn | Reliance on spectral contrast; sub-pixel plastics (<10 m) often missed; confusion with organic matter (algae, foam) |

| Basu et al. (2021) [2] | SVR (regression) + thresholding on spectral features | Sentinel-2 (bands B2,B3,B4,B6,B8,B11) with NDWI & FDI indices | Coastal waterbodies (case studies in Asia) | 98.4% pixel-level detection accuracy reported | Supervised on limited scenes; may overfit specific water conditions; not a fully deep learning approach (manual feature selection) |

| Sannigrahi et al. (2022) [3] | Random Forest and SVM classifiers on spectral indices (FDI, PI, NDVI, etc.) | Sentinel-2 MSI, multi-band composites | Coastal zones (global test sites) | ~92–98% precision (RF); up to 89–100% SVM accuracy on validation | High variance across classes; performance drops if debris spectral signature is weak; index thresholds need tuning per region |

| Duarte et al. (2023) [4] | XGBoost boosted-tree classifier (supervised learning) | Sentinel-2 multispectral + multiple water indices (NDSI, MNDWI, OSI, FDI, etc.) | Coastal and estuarine waters (e.g., Portugal/Brazil) | >95% overall classification accuracy | Primarily detects large aggregations; limited by quality of index inputs and possible false positives from look-alike spectra |

| Booth et al. (2023) [8] | U-Net CNN (semantic segmentation) with two versions (high-precision vs. balanced) | Sentinel-2 MARIDA dataset (multiclass labels) for training | Global (trained on MARIDA; tested on Honduras, Philippines, India, etc.) | Precision 95% (high-precision model); F1 ≈ 87–88% balanced | Requires extensive label refinement and negative examples; still yields some false positives in low-density areas; performance drops outside Sentinel-2 (no IR bands in other sensors) |

| NASA IMPACT (2023) [14] | YOLO-based object detector (deep learning) | PlanetScope cubesat imagery (3 m, RGB + NIR); 256 × 256 tiles | Bay Islands (Honduras), Accra (Ghana), Mytilene (Greece)—known debris events | F1-score ≈ 0.85 at IoU = 0.5 on test data | Constrained by 3 m resolution—cannot see microdebris; some confusion with floating vegetation; needs frequent re-training for new locations due to limited spectral bands |

| Source | Resolution | Samples | Labels | Annotation | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UAV orthomosaics | 2–3 cm | ~450 patches | ~3200 objects | Bounding boxes (YOLO) | Object detection |

| Sentinel-2 | 10–20 m | ~600 chips | 140 positive | Polygon masks | Semantic segmentation |

| CMEMS currents | 1/12°, daily | continuous | u,v vectors | – | Drift modeling |

| NOAA GFS winds | 0.25°, 6-hourly | continuous | u,v vectors | – | Drift modeling |

| Component | Model | Input Size | Init. Weights | Optimizer | LR/Schedule | Batch | Epochs | Augmentations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Object detection | YOLOv5s (PyTorch 1.13) | 1280 × 1280 (UAV) | COCO | SGD (mom = 0.9, wd = 5 × 10−4) | 0.01, cosine | 16 | 100 (ES @10) | Mosaic, flip, rotate ±15°, scale ± 10%, brightness/contrast |

| Segmentation | U-Net (ResNet-34) | 512 × 512 (S2 tiles) | ImageNet | Adam | 1 × 10−3, poly (0.9) | 8 | 200 (ES @15) | Flip, rotate 90°, translate, color jitter |

| Segmentation | U-Net++ (ResNet-34) | 512 × 512 (S2 tiles) | ImageNet | Adam | 1 × 10−3, poly (0.9) | 8 | 200 (ES @15) | Flip, rotate 90°, translate, color jitter |

| Model | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | IoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv5 (UAV detection) | 0.910 | 0.880 | 0.895 | 0.62 |

| U-Net (S2 segmentation) | 0.790 | 0.760 | 0.775 | 0.71 |

| U-Net++ (S2 segmentation) | 0.850 | 0.830 | 0.840 | 0.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cernian, A.; Iliuta, M.-E. Empowering Sustainability Through AI-Driven Monitoring: The DEEP-PLAST Approach to Marine Plastic Detection and Trajectory Prediction for the Black Sea. Water 2025, 17, 3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223318

Cernian A, Iliuta M-E. Empowering Sustainability Through AI-Driven Monitoring: The DEEP-PLAST Approach to Marine Plastic Detection and Trajectory Prediction for the Black Sea. Water. 2025; 17(22):3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223318

Chicago/Turabian StyleCernian, Alexandra, and Miruna-Elena Iliuta. 2025. "Empowering Sustainability Through AI-Driven Monitoring: The DEEP-PLAST Approach to Marine Plastic Detection and Trajectory Prediction for the Black Sea" Water 17, no. 22: 3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223318

APA StyleCernian, A., & Iliuta, M.-E. (2025). Empowering Sustainability Through AI-Driven Monitoring: The DEEP-PLAST Approach to Marine Plastic Detection and Trajectory Prediction for the Black Sea. Water, 17(22), 3318. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223318