The Impact of Catastrophic Flooding on Nitrogen Sources Composition in an Intensively Human-Impacted Lake: A Case Study of Baiyangdian Lake

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

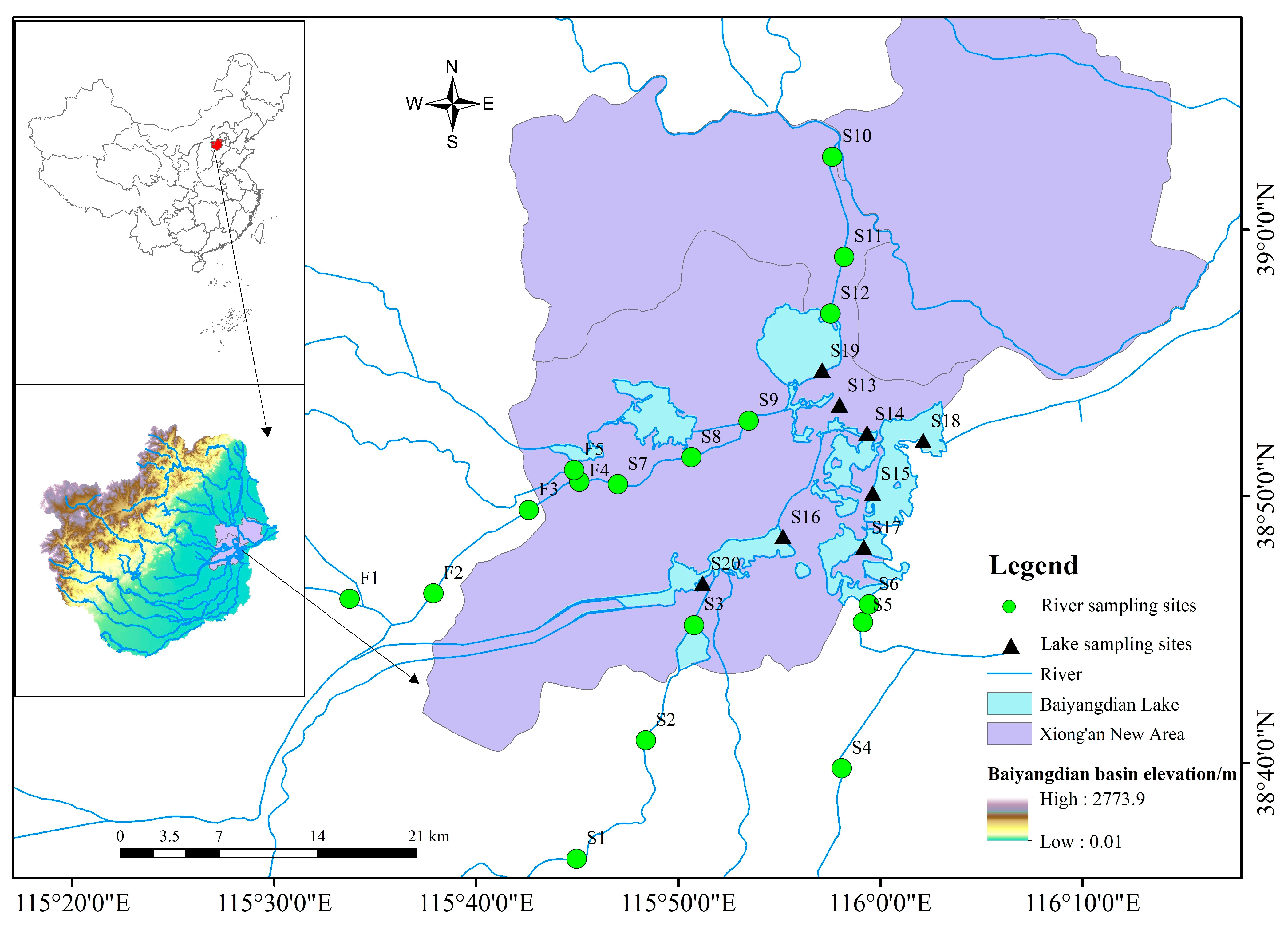

2.1. In Situ Measurements

2.2. Laboratory Analysis

2.3. Nitrate Nitrogen and Oxygen Isotope Analysis

2.4. Bayesian Isotope Mixing Model

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Hydrochemical Characteristics

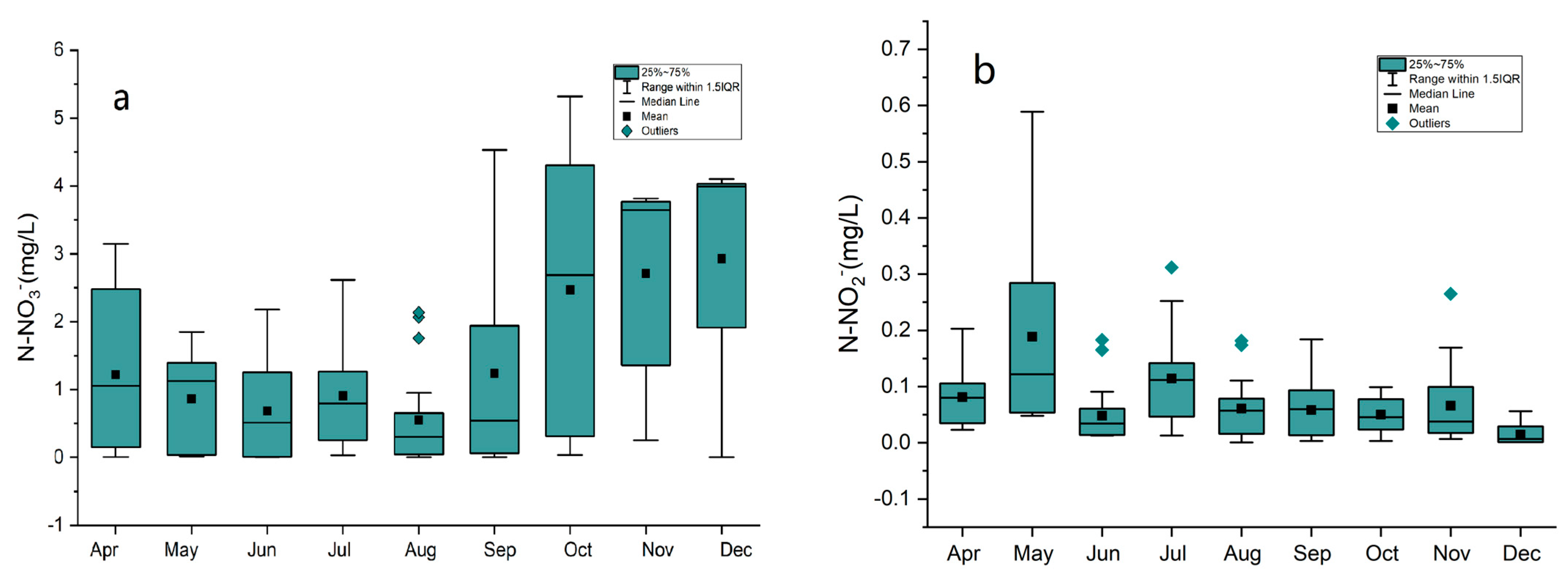

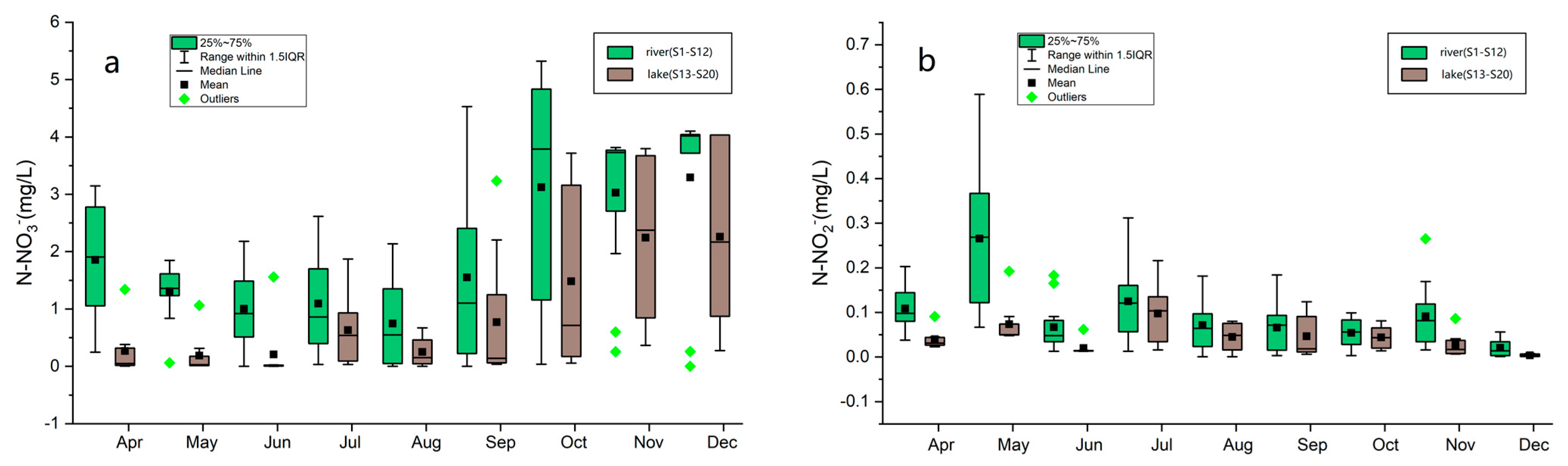

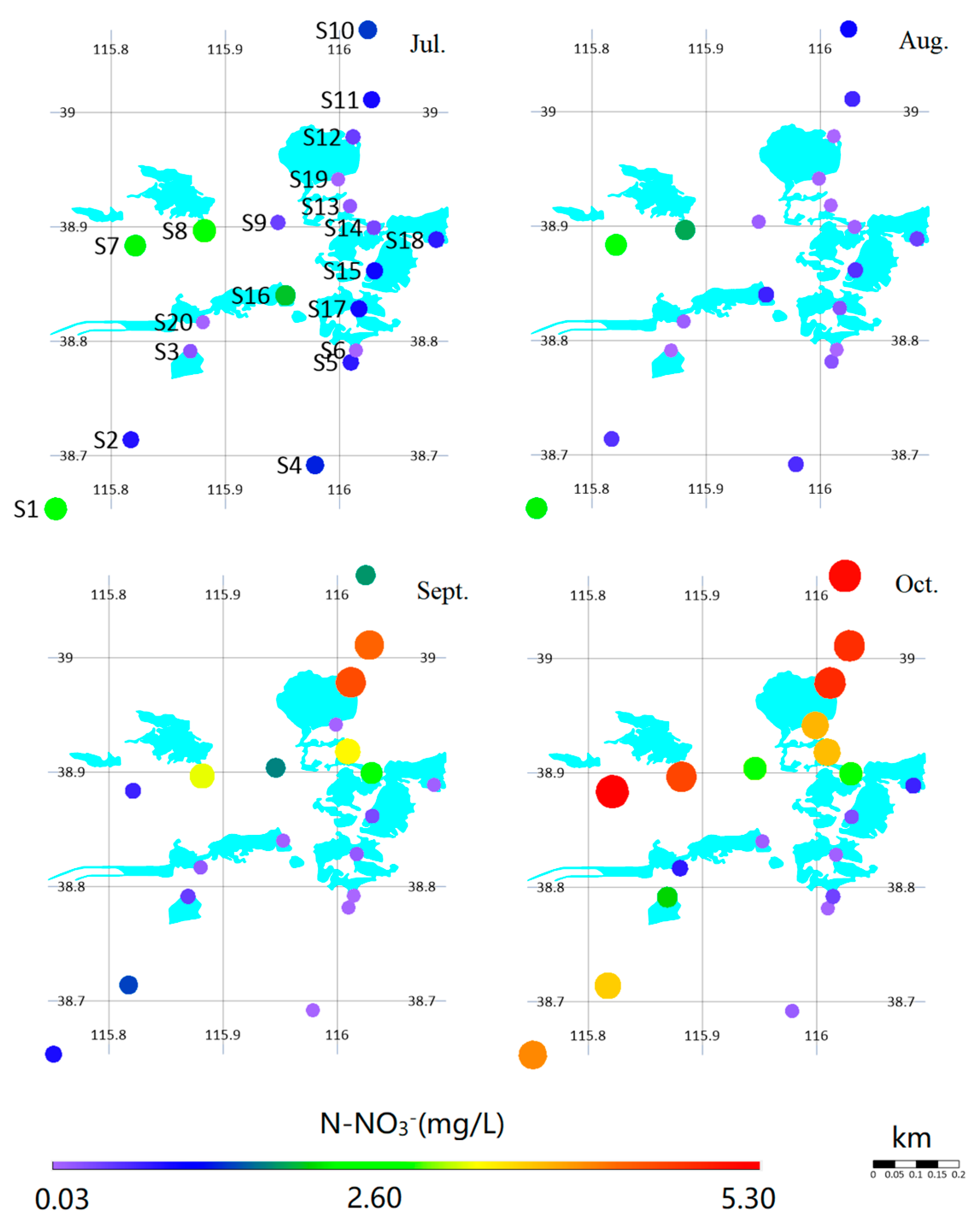

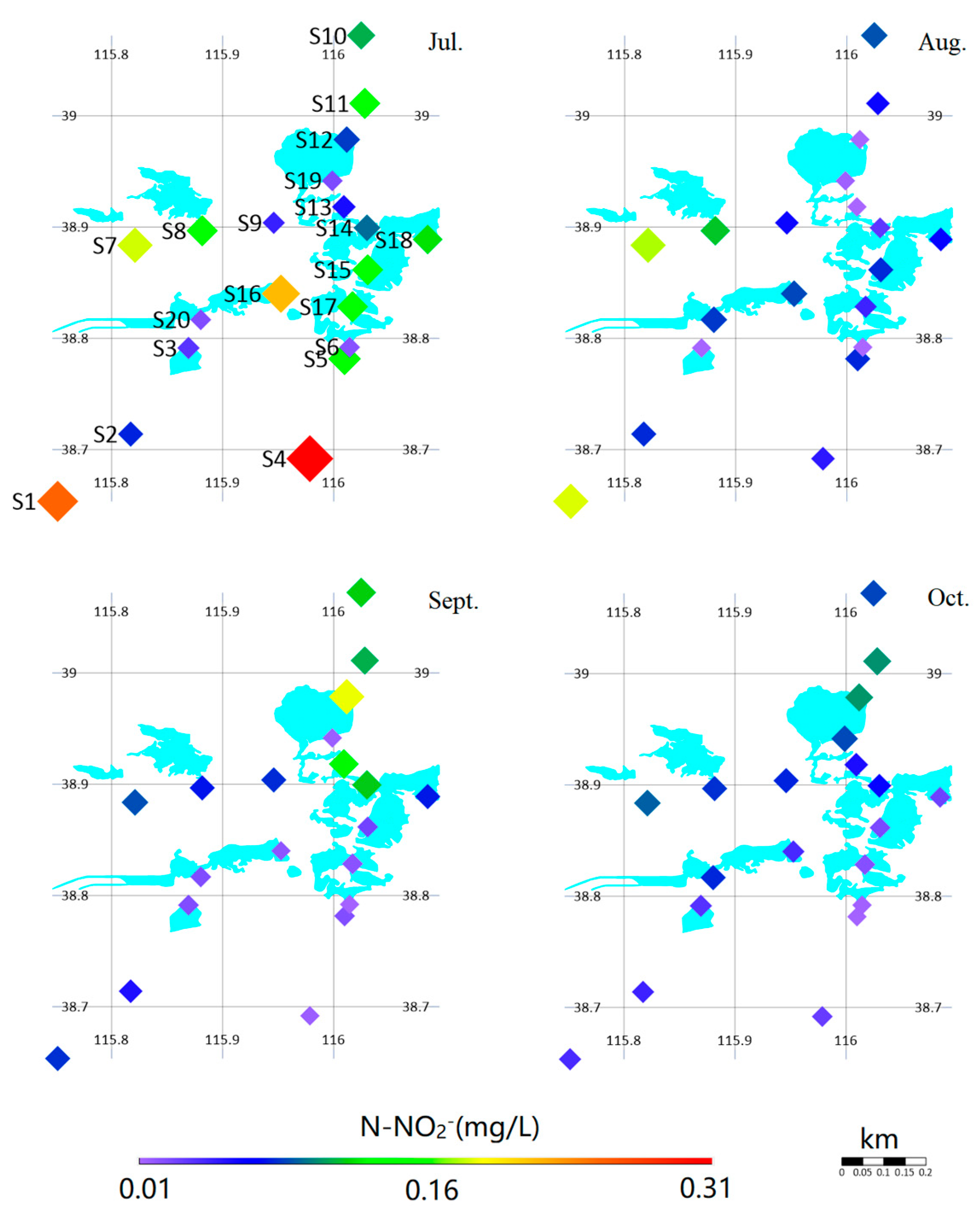

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variations in Nitrate and Nitrite Concentrations

4. Discussion

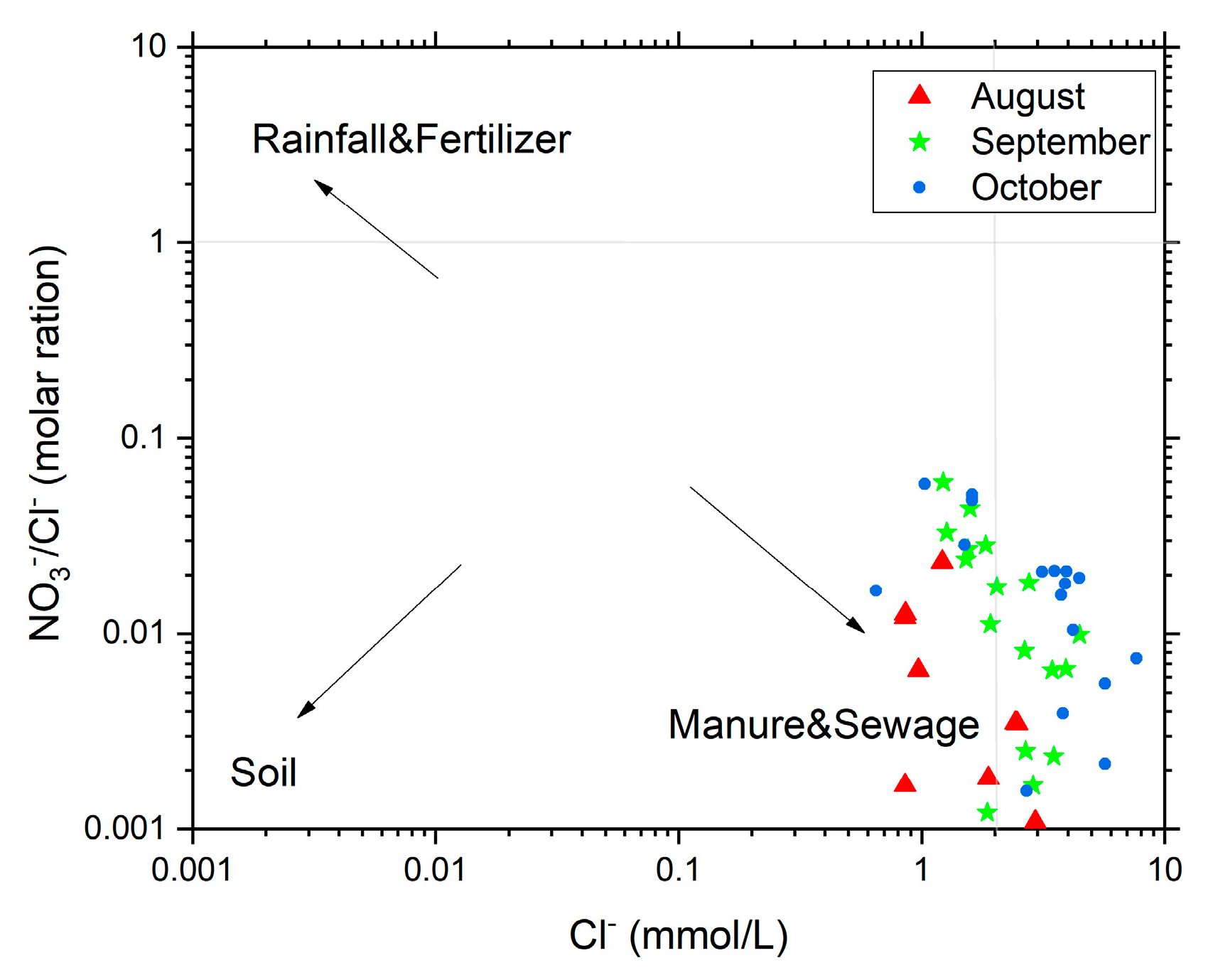

4.1. Identification Using NO3−/Cl− Molar Ratios

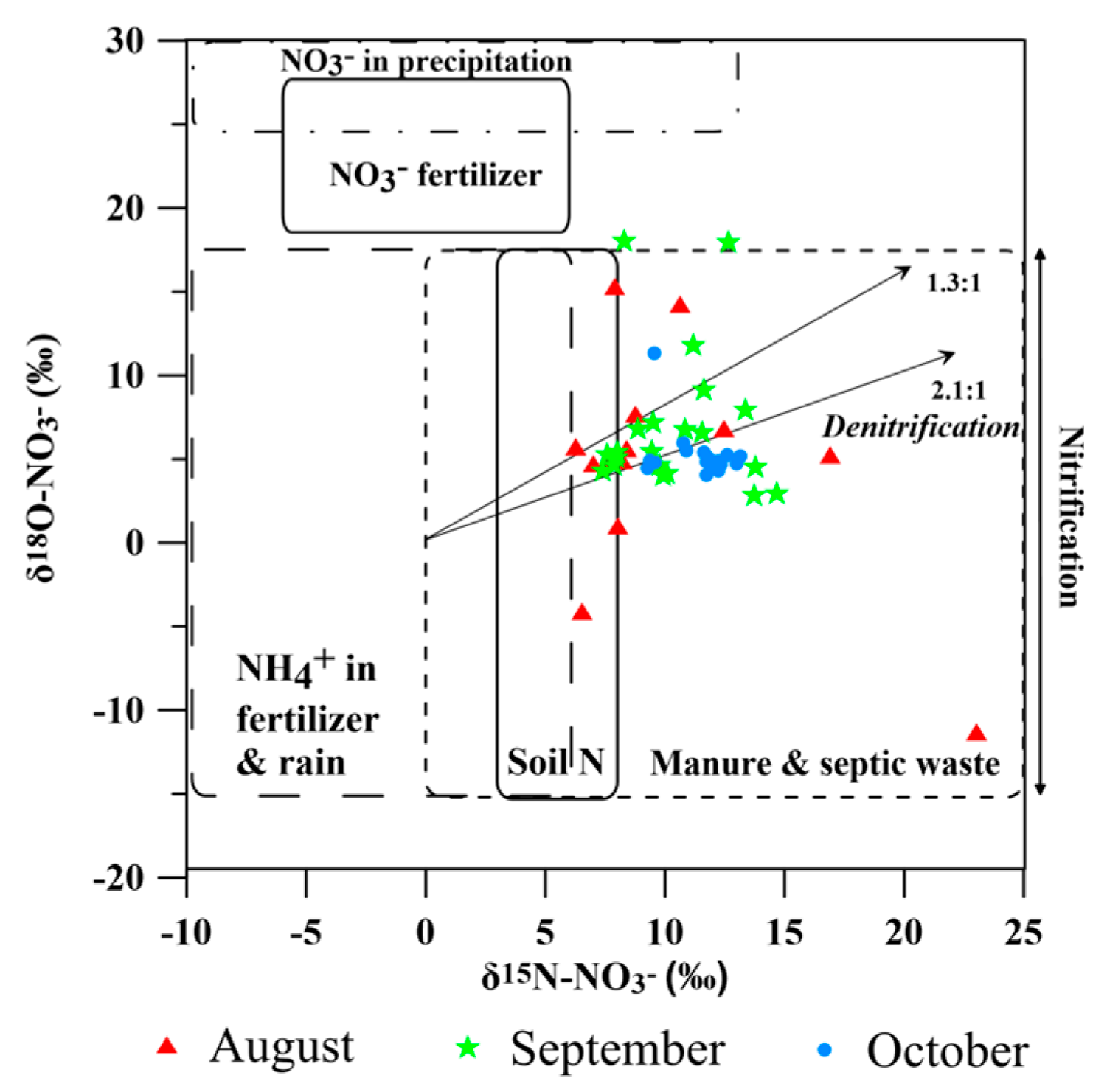

4.2. Nitrate Sources Constrained by Chemical and Isotopic Compositions (δ15N and δ18O)

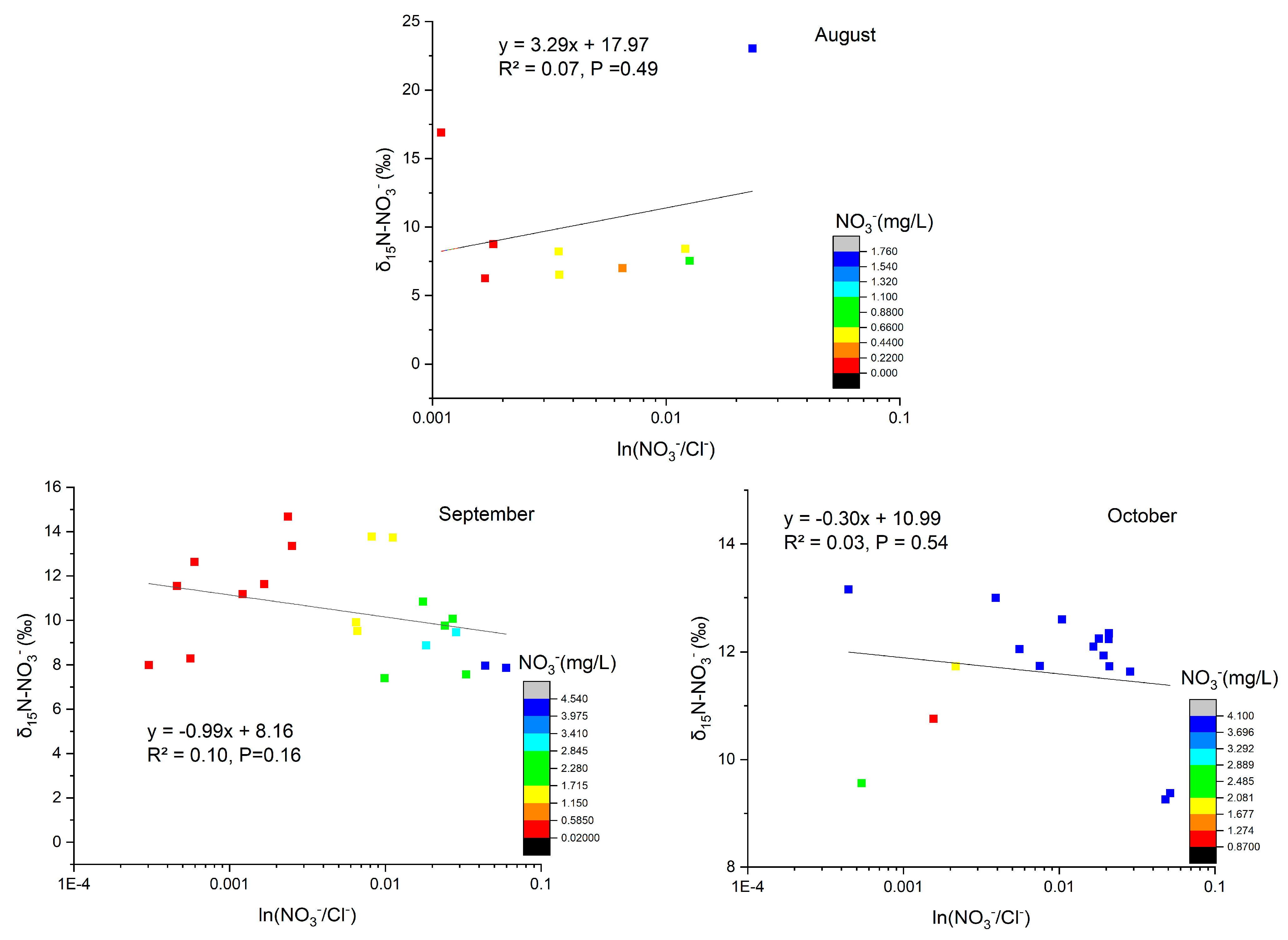

4.3. Nitrate Transport and Transformation

4.4. Uncertainty Analysis of Source Apportionment Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meghdadi, A.; Javar, N. Quantification of spatial and seasonal variations in the proportional contribution of nitrate sources using a multi-isotope approach and Bayesian isotope mixing model. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, R.; Hirsh, A.; Exner, M.; Little, N.; Kloppenborg, K. Applicability of the dual isotopes δ15N and δ18O to identify nitrate in groundwater beneath irrigated cropland. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2018, 220, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keys, T.A.; Caudill, M.F.; Scott, D.T. Storm effects on nitrogen flux and longitudinal variability in a river–reservoir system. River Res. Appl. 2019, 35, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, J.A.; Emanuel, R.E.; Nichols, E.G.; Vose, J.M. Extreme Flooding and Nitrogen Dynamics of a Blackwater River. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, F.-J.; Li, S.-L.; Waldron, S.; Wang, Z.-J.; Oliver, D.M.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.-Q. Rainfall and conduit drainage combine to accelerate nitrate loss from a karst agroecosystem: Insights from stable isotope tracing and high-frequency nitrate sensing. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, W.L.; Wohl, E.; Sinha, T.; Sabo, J.L. Sedimentation and sustainability of western American reservoirs. Water Resour. Res. 2010, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondolf, G.M.; Gao, Y.; Annandale, G.W.; Morris, G.L.; Jiang, E.; Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Carling, P.; Fu, K.; Guo, Q.; et al. Sustainable sediment management in reservoirs and regulated rivers: Experiences from five continents. Earths Future 2014, 2, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, H.; Kang, L.; Zhu, G.; Paerl, H.W.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; Zhu, M.; Zou, W.; Qin, B.; et al. Nitrate sources and transformations in a river-reservoir system: Response to extreme flooding and various land use. J. Hydrol. 2024, 638, 131491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Michalak, A.M.; Pahlevan, N. Widespread global increase in intense lake phytoplankton blooms since the 1980s. Nature 2019, 574, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieder, R.; Benbi, D.K.; Reichl, F.X. Reactive Water-Soluble Forms of Nitrogen and Phosphorus and Their Impacts on Environment and Human Health. In Soil Components and Human Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, B.; Deng, J.; Shi, K.; Wang, J.; Brookes, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Paerl, H.W.; Wu, L.; et al. Extreme Climate Anomalies Enhancing Cyanobacterial Blooms in Eutrophic Lake Taihu, China. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR029371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk, T.R.; Mohn, J.; Decock, C.; Lewicka-Szczebak, D.; Harris, E.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Kiese, R.; Wolf, B. The nitrogen cycle: A review of isotope effects and isotope modeling approach-es. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 105, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, J.; Toor, G.S. Composition, sources, and bioavailability of nitrogen in a longitudinal gradient from freshwater to estuarine waters. Water Res. 2018, 137, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, C.; Elliott, E.M.; Wankel, S.D. Tracing Anthropogenic Inputs of Nitrogen to Ecosystems. In Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 375–449. [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, M.; Mayer, B.; Nightingale, M.; Laceby, J.P. Tracing nitrate sources with a combined isotope approach (δ15NNO3, δ18ONO3 and δ11B) in a large mixed-use watershed in southern Alberta, Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.N.M.; Do, T.N.; Matiatos, I.; Panizzo, V.N.; Trinh, A.D. Stable isotopes as an effective tool for N nutrient source identification in a heavily urbanized and agriculturally intensive tropical lowland basin. Biogeochemistry 2020, 149, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, K.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, F.; Tonina, D.; Shi, W.; Chen, C. Tracking nitrogen pollution sources in plain watersheds by combining high-frequency water quality monitoring with tracing dual nitrate isotopes. J. Hydrol. 2020, 581, 124439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, J.N.; Aber, J.D.; Erisman, J.W.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Howarth, R.W.; Cowling, E.B.; Cosby, B.J. The nitrogen cascade. BioScience 2003, 53, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattinson, S.; Garciaruiz, R.; Whitton, B.A. Spatial and seasonal variation in denitrification in the Swale–Ouse system, a river continuum. Sci. Total Environ. 1998, 210–211, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweimüller, I.; Zessner, M.; Hein, T. Effects of climate change on nitrate loads in a large river: The Austrian Danube as example. Hydrological Processes. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, I.; Otero, N.; Soler, A.; Green, A.J.; Soto, D.X. Agricultural and urban delivered nitrate pollution input to Mediterranean temporary freshwaters. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 294, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utom, A.U.; Werban, U.; Leven, C.; Müller, C.; Knöller, K.; Vogt, C.; Dietrich, P. Groundwater nitrification and denitrification are not always strictly aerobic and anaerobic processes, respectively: An assessment of dual-nitrate isotopic and chemical evidence in a stratified alluvial aquifer. Biogeochemistry 2020, 147, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhullah, W.; Yaccob, N.S.; Syakir, M.; Muhammad, S.A.; Yue, F.-J.; Li, S.-L. Nitrate sources and processes in the surface water of a tropical reservoir by stable isotopes and mixing model. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 700, 134517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Huang, H.; Mei, K.; Xia, F.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Zhang, M.; Ji, X. Riverine nitrate source apportionment using dual stable isotopes in a drinking water source watershed of southeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 137975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, C.; Aravena, R. Nitrate Isotopes in Groundwater Systems. In Environmental Tracers in Subsurface Hydrology; Springer: New York City, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 261–297. [Google Scholar]

- Minet, E.; Goodhue, R.; Meier-Augenstein, W.; Kalin, R.; Fenton, O.; Richards, K.; Coxon, C. Combining stable isotopes with contamination indicators: A method for improved investigation of nitrate sources and dynamics in aquifers with mixed nitrogen inputs. Water Res. 2017, 124, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, L.; Mayer, B. Isotopic Assessment of Sources of Surface Water Nitrate within the Oldman River Basin, Southern Alberta, Canada. Water Air Soil Pollut. Focus 2004, 4, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Botte, J.; De Baets, B.; Accoe, F.; Nestler, A.; Taylor, P.; Van Cleemput, O.; Berglund, M.; Boeckx, P. Present Limitations and Future Prospects of Stable Isotope Methods for Nitrate Source Identification in Surface and Groundwater. Water Res. 2009, 43, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freyer, H.D. Seasonal variation of 15N/l4N ratios in atmospheric nitrate species. Tellus Ser. B-Hemical Phys. Mete-Orol. 1991, 43, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xi, B.; Xu, Q.; Gao, R.; Lu, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, H. Application of stable isotope on nitrate pollution researches of surface water. J. Lake Sci. 2013, 25, 11. Available online: https://www.jlakes.org/hpkx/article/abstract/20130501 (accessed on 9 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.-Q.; Li, S.-L.; Lang, Y.-C.; Xiao, H.-Y. Using δ15N- and δ18O-Values To Identify Nitrate Sources in Karst Ground Water, Guiyang, Southwest China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 6928–6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.-L.; Liu, C.-Q.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Chetelat, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, F. Assessment of the Sources of Nitrate in the Changjiang River, China Using a Nitrogen and Oxygen Isotopic Approach. Environmental. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1573–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, M.; Zeng, W.; Wu, C.; Chen, G.; Meng, Q.; Hao, X.; Peng, Y. Impact of organic carbon on sulfide-driven autotrophic denitrification: Insights from isotope fractionation and functional genes. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, Y.; Hosono, T.; Onodera, S.-I.; Siringan, F.; Buapeng, S.; Delinom, R.; Yoshimizu, C.; Tayasu, I.; Nagata, T.; Taniguchi, M.; et al. Sources of nitrate and ammonium contamination in groundwater under developing Asian megacities. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 3219–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, J.W.; Valiela, I. Linking nitrogen in estuarine producers to land-derived sources. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1998, 43, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, C. Tracing nitrogen sources and cycling in catchments. In Isotope Tracers in Catchment Hydrology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; pp. 519–576. ISBN 9780444815460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.; Bollwerk, S.M.; Mansfeldt, T.; Hütter, B.; Veizer, J. The oxygen isotope composition of nitrate generated by nitrification in acid forest floors. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2001, 65, 2743–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Xie, R.; Hao, Y.; Lu, J. Quantitative identification of nitrate pollution sources and uncertainty analysis based on dual isotope approach in an agricultural watershed. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 229, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiatos, I.; Wassenaar, L.I.; Monteiro, L.R.; Venkiteswaran, J.J.; Gooddy, D.C.; Boeckx, P.; Sacchi, E.; Yue, F.; Michalski, G.; Alonso-Hernández, C.; et al. Global patterns of nitrate isotope composition in rivers and adjacent aquifers reveal reactive nitrogen cascading. Commun. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Lin, C.; Tang, C. Hydrology, environment and ecological evolution of Lake Baiyangdian since 1960s. J. Lake Sci. 2020, 32, 1333–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.P. Research on Water Pollution Characteristics of Baiyangdian and Water Quality Enhancement Technology Based on Plant Purification. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.L. A Comparative Study on the Simulation of Groundwater Evapotranspiration Changes Caused by Different Water Use Methods—Taking the Agricultural Irrigation Area and Ecological Water Recharge Area in the North China Plain as Examples. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Xu, G.; Tang, G.; Zhang, W.; Min, A. Temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of hourly heavy rainfall of the “23.7” heavy rainstorm event in North China. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 47, 778–788. Available online: http://dqkxxb.cnjournals.org/dqkxxb/article/abstract/20240508?st=search (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Li, F.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Shao, C.; Jiang, J. Synoptic-scale system characteristics and mechanisms of the “23.7” extreme rainstorm in North China. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 48, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkins, R.; Tranter, M.; Dowdeswell, J.A. The hydrochemistry of runoff from a ‘cold-based’ glacier in the High Artic (Scott Turnerbreen, Svalbard). Hydrol. Process. 1998, 12, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.M.; Hart, S.C. Diffusion technique for preparing salt solutions, kjeldahl digests, and persulfate digests for nitrogen-15 Analysis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1996, 60, 1846–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesako, H. Double-plunger pump system flow injection spectrophotometric determination of inorganic nitrogen in soil extracts (part 2): Flow injection analysis of nitrate nitrogen in soil extracts. Jpn. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1991, 62, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Czerwionka, K. Influence of dissolved organic nitrogen on surface waters. Oceanologia 2015, 58, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Yang, P.; Xie, S.; Sheng, T.; Luo, D. Sources and transformations of nitrate of the subterranean river system in Jin-foshan Karst World Heritage. J. Lake Sci. 2019, 31, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; De Baets, B.; Van Cleemput, O.; Hennessy, C.; Berglund, M.; Boeckx, P. Use of a Bayesian isotope mixing model to estimate proportional contributions of multiple nitrate sources in surface water. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 161, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, A.C.; Inger, R.; Bearhop, S.; Jackson, A.L. Source Partitioning Using Stable Isotopes: Coping with Too Much Variation. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, B.C.; Jackson, A.L.; Ward, E.J.; Parnell, A.C.; Phillips, D.L.; Semmens, B.X. Analyzing mixing systems using a new generation of Bayesian tracer mixing models. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Jia, G.; Chen, J. Nitrate sources and watershed denitrification inferred from nitrate dual isotopes in the Beijiang River, south China. Biogeochemistry 2009, 94, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, C.; Zheng, L.; Dong, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, C. Identification of nitrate sources and transformations in basin using dual isotopes and hydrochemistry combined with a Bayesian mixing model: Application in a typical mining city. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leger, A.; Rebbert, C.; Webster, J. Cl-rich biotite and amphibole from Black Rock Forest, Cornwall, New York. Am. Miner. 1996, 81, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anornu, G.; Gibrilla, A.; Adomako, D. Tracking nitrate sources in groundwater and associated health risk for rural communities in the White Volta River basin of Ghana using isotopic approach (δ15N, δ18ONO3 and 3H). Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 603–604, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B. Study on the Characteristics of Salinity Change and Water Quality Effect in Baiyangdian Waterfill Area. Master’s Thesis, Hebei University of Engineering, Handan, China, 2023. (In English). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Long, W. Tracing nitrate pollution sources and transformations in the over-exploited groundwater region of north China using stable isotopes. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2018, 218, S0169772217302322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, S.; Li, Q.; Yu, H. Application of the dual-isotope approach and Bayesian isotope mixing model to identify nitrate in groundwater of a multiple land-use area in Chengdu Plain, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddau, R.; Cidu, R.; Da Pelo, S.; Carletti, A.; Ghiglieri, G.; Pittalis, D. Source and fate of nitrate in contaminated groundwater systems: Assessing spatial and temporal variations by hydrogeochemistry and multiple stable isotope tools. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 647, 1121–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zheng, T.; Zheng, X.; Hao, Y.; Yuan, R. Nitrate source apportionment in groundwater using Bayesian isotope mixing model based on nitrogen isotope fractionation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, K.K.; Hooper, A.B. O2 and H2O are each the source of one O in NO2 produced from NH3 by Nitrosomonas: 15N-NMR evidence. FEBS Lett. 1983, 164, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.B.; Whitcomb, R.F.; Tully, J.G. Spiroplasmas from coleopterous insects: New ecological dimensions. Microb. Ecol. 1982, 8, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumft, W.G. Cell biology and molecular basis of denitrification. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61, 533–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhan, J.; Deng, X.; Ling, Y. Influencing factors of lake eutrophication in China: A case study in 22 lakes in China. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 21, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

| Site ID | Temperature Range (°C) | pH Range | Dissolved Oxygen (DO) Range (mg/L) | Electrical Conductivity (EC) Range (μS/cm) | Oxidation–Reduction Potential (ORP) Range (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 20.5–30.2 | 8.10–8.29 | 1.58–5.60 | 997–1341 | 306–326 |

| S2 | 19.9–29.4 | 8.14–8.35 | 1.70–5.85 | 1447–1598 | 302–322 |

| S3 | 19.3–30.6 | 8.00–8.21 | 1.29–4.63 | 1453–1887 | 304–304 |

| S4 | 20.9–30.5 | 7.98–8.50 | 1.75–7.98 | 326–788 | 308.5–326 |

| S5 | 20.0–30.0 | 8.39–9.34 | 1.72–19.64 | 1331–1506 | 299–323 |

| S6 | 20.0–30.6 | 8.41–8.46 | 1.88–8.95 | 1073–1246 | 303–321 |

| S7 | 18.22–30.6 | 7.70–8.04 | 1.68–6.28 | 670–1087 | 305–321 |

| S8 | 19.5–30.4 | 7.73–8.27 | 1.66–5.71 | 640–756 | 305–327 |

| S9 | 18.6–27.2 | 7.77–8.54 | 1.14–3.13 | 500–652 | 301–320 |

| S10 | 19.6–32.7 | 8.25–8.73 | 1.41–8.33 | 463–654 | 297–323 |

| S11 | 19.2–32.3 | 8.31–8.94 | 1.68–7.80 | 366–658 | 303–327 |

| S12 | 18.7–27.8 | 8.57–8.68 | 1.90–6.88 | 454–656 | 298–320 |

| S13 | 19.4–27.3 | 7.85–8.52 | 1.24–4.09 | 474–648 | 295–320 |

| S14 | 19.6–30.0 | 7.88–8.45 | 1.04–6.65 | 485–645 | 304–323 |

| S15 | 19.1–30.4 | 8.03–8.74 | 1.63–7.75 | 526–718 | 300–322 |

| S16 | 18.25–30.6 | 7.82–8.05 | 0.49–5.24 | 517–852 | 310–322 |

| S17 | 20.9–30.9 | 7.89–8.47 | 1.48–8.45 | 495–690 | 320–324 |

| S18 | 20.6–31.5 | 7.85–8.52 | 1.57–9.68 | 494–691 | 319–324 |

| S19 | 20.6–31.9 | 7.85–8.50 | 1.59–9.23 | 497–687 | 319–324 |

| S20 | 20.6–31.2 | 7.84–8.51 | 1.65–8.91 | 497–688 | 319–325 |

| Month | Hydrological Period | δ15N-NO3− (‰) Range | δ18O-NO3− (‰) Range | Major Pollution Sources | Key Processes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August | Flood Period | 0~23.0 | −11.3~5.3 | Mix of Soil N (SN) and Manure & Sewage (MS) | Dilution effect, scouring action |

| September | Post-flood Period | 0~18.49 | −1.31~11.09 | Dominated by Manure & Sewage (MS) | Pollution rebound, nitrification |

| October | Post-flood Period | 0~58.23 | −5.00~25.20 | Manure & Sewage (MS), Denitrification | Ongoing nitrification, denitrification |

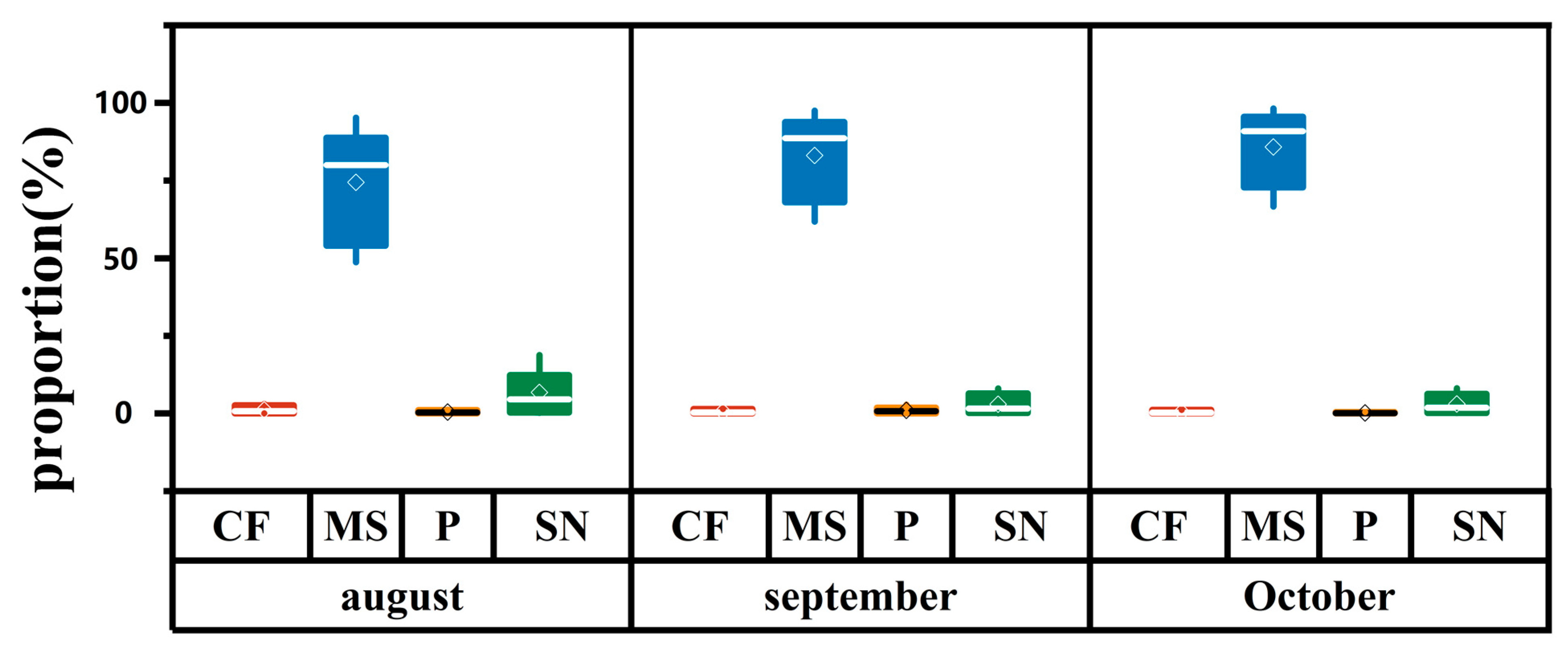

| Source | August (Flood Period) | September (Post-Flood Period) | October (Stable Flow Period) | Key Characteristics and Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS (%) | 84.0 | 90.3 | 83.7 | Absolutely dominant source (domestic sewage and livestock waste). Contribution further increased post-flood (Sept.), indicating a strong rebound of point-source pollution as water levels receded, and remained dominant during the stable period. |

| SN (%) | 12.3 | 6.4 | 14.8 | Secondary source (soil nitrogen). Relatively higher contribution during the flood (Aug.) due to scouring effects, then decreased, indicating its contribution is hydrologically driven, but overall much lower than MS. |

| CF (%) | 2.6 | 1.5 | 1.1 | Minor contribution (chemical fertilizer). A decreasing trend month-by-month, potentially related to post-growing season uptake; overall contribution is very low, reflecting limited direct leaching impact from agricultural fertilizer in the basin. |

| P (%) | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.4 | Negligible contribution (atmospheric precipitation). Decreased significantly each month; its inherent nitrate content is low and likely subject to rapid dilution/transformation, resulting in minimal direct impact on the nitrate load in the water body. |

| Pollution Source | August (Flood Period) | September (Post-Flood Period) | October (Stable Period) | Observations and Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | 0.309 | 0.551 | 0.421 | Uncertainty peaked in the post-flood period (September), reflecting the complex response of point-source pollution to drastic hydrological changes. |

| SN | 0.727 | 0.651 | 0.489 | Uncertainty was consistently the highest among all sources but decreased significantly over time, indicating the strongest spatiotemporal variability. |

| CF | 0.157 | 0.122 | 0.090 | Uncertainty was relatively low and decreased continuously, corresponding to a stable contribution rate. |

| P | 0.050 | 0.077 | 0.028 | Uncertainty remained the lowest among all sources, indicating the most stable contribution, reaching its minimum in the stable period (October). |

| Overall Uncertainty | Relatively High | Highest | Relatively Low | Systemic uncertainty was most pronounced in the post-flood period and subsequently stabilized. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Hou, X.; Meng, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, S.; Cao, J. The Impact of Catastrophic Flooding on Nitrogen Sources Composition in an Intensively Human-Impacted Lake: A Case Study of Baiyangdian Lake. Water 2025, 17, 3309. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223309

Zhang Y, Hou X, Meng L, Wang Y, Ma S, Cao J. The Impact of Catastrophic Flooding on Nitrogen Sources Composition in an Intensively Human-Impacted Lake: A Case Study of Baiyangdian Lake. Water. 2025; 17(22):3309. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223309

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yan, Xianglong Hou, Lingyao Meng, Yunxia Wang, Shaopeng Ma, and Jiansheng Cao. 2025. "The Impact of Catastrophic Flooding on Nitrogen Sources Composition in an Intensively Human-Impacted Lake: A Case Study of Baiyangdian Lake" Water 17, no. 22: 3309. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223309

APA StyleZhang, Y., Hou, X., Meng, L., Wang, Y., Ma, S., & Cao, J. (2025). The Impact of Catastrophic Flooding on Nitrogen Sources Composition in an Intensively Human-Impacted Lake: A Case Study of Baiyangdian Lake. Water, 17(22), 3309. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223309