A Moving-Window Based Method for Floor Water Inrush Risk Assessment in Coal Mines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of the Study Area

2.1. Geographical Condition

2.2. Geological Setting

2.3. Hydrological and Geological Conditions

3. Main Evaluation Indicators for the Risk of Floor Water Gushing

- (1)

- Water pressure: The water pressure acting on the coal seam floor is strongly positively correlated with the risk of water inrush. Higher water pressure not only increases the likelihood of floor water inrush but also enhances the softening effect on the aquiclude, thereby reducing its strength. According to hydrogeological and borehole data, the water level of the Ordovician limestone aquifer in the study area has remained stable at approximately +371 m, and the calculated water pressure at the coal seam floor ranges from 0.348 to 2.947 MPa.

- (2)

- Coal seam thickness: Greater coal seam thickness leads to more extensive and intense overburden failure induced by mining, which facilitates the formation of water-conducting channels that connect aquifers. In addition, during the extraction of thick seams, the stress distribution borne by the floor becomes more complex, and the manifestation of mining pressure is more pronounced, thereby promoting the further development of fractures in the floor strata and increasing the risk of water inrush. According to borehole data analysis, the thickness of the No. 5 coal seam in the study area ranges from 0.34 to 5.30 m.

- (3)

- Coal seam burial depth: The risk of floor water inrush increases with greater burial depth. Increased depth directly influences the stress distribution and the height of overburden failure after mining. As burial depth increases, the original rock stress acting on the coal seam floor intensifies, making the floor strata more prone to fracturing and thus creating pathways for water inrush. Borehole data analysis indicates that the burial depth of the No. 5 coal seam in the study area ranges from 182.93 to 584.87 m.

- (4)

- Coal seam dip angle: The dip angle of the coal seam directly affects the movement pattern and stress distribution of the overburden after mining. Larger dip angles result in more significant gravitational components during mining, leading to asymmetric rock deformation and sliding, as well as an enlarged failure range, thereby increasing the probability of water inrush. Moreover, the dip angle determines the stress difference in mining and water pressure on both sides of the panel, thereby influencing the location of potential water inrush. Borehole data analysis shows that the dip angle of the No. 5 coal seam in the study area ranges from 2.0° to 18.0°.

- (5)

- Fault fractal dimension: Faults, as geological structures formed by rock rupture under stress and relative displacement, influence floor water inrush primarily in two aspects. First, faults can serve as water-conducting channels, directly connecting aquifers with mining spaces and triggering water inrush. Even when the fault itself has low permeability, secondary fractures generated in its surrounding zones due to stress concentration may form additional water-conducting pathways, thereby indirectly enhancing groundwater migration capacity. Second, the cutting effect of faults can disrupt the continuity of aquicludes, weakening their capacity to withstand aquifer pressure and thus inducing water inrush.

- (6)

- Aquiclude thickness: The aquiclude is generally composed of one or more water-resisting strata, which serve to block the hydraulic connection between the aquifer and the coal seam and inhibit fracture development. A greater thickness of the aquiclude prevents mining-induced fractures from penetrating the aquifer, thereby stopping pressurized water from entering the working face and ensuring safe coal extraction. Thus, the thicker the aquiclude, the lower the risk of floor water inrush during coal mining. According to borehole data analysis in the study area, the thickness of the aquiclude underlying the No. 5 coal seam ranges from 8.20 to 77.52 m.

4. Methods

4.1. Global Evaluation Method

4.1.1. Analytic Hierarchy Process

4.1.2. Establishment of the Global Evaluation Model

- (1)

- Global standardization of evaluation indicators

- (2)

- Establishment of the global evaluation model

4.2. Local Evaluation Method

4.2.1. Monte Carlo Analytic Hierarchy Process (MAHP)

- (1)

- Strong subjectivity: The outcomes are highly dependent on the knowledge, experience, and preferences of decision-makers. Consequently, different experts may construct substantially different judgment matrices, which reduces the stability and objectivity of the results.

- (2)

- Strict independence assumption: AHP presumes that all factors are mutually independent. However, in complex real-world problems, interdependence and interactions among factors are common, making this assumption difficult to satisfy.

- (3)

- Limited capacity to address uncertainty: AHP demonstrates insufficient capability when applied to problems involving fuzzy information or high levels of uncertainty.

4.2.2. Establishment of Local Evaluation Model

- (1)

- Neglect of local heterogeneity, leading to imprecise risk localization. In actual mines, local geological features—such as minor faults, fracture zones, abrupt changes in aquiclude thickness, and abnormal water pressure areas—are often the key triggers of floor water inrush. Within a global evaluation framework, these local factors are likely to be downplayed or overlooked, resulting in misidentification of water inrush points.

- (2)

- Fixed indicator weights with poor adaptability. The global evaluation method generally adopts uniform indicator weights, which may reflect regional-scale patterns but fail to capture the dominant factors specific to different sub-areas, thereby reducing adaptability.

- (3)

- Insufficient use of small-scale data, limiting evaluation accuracy. Global evaluation relies heavily on macro-scale regional data (e.g., average aquiclude thickness or overall water pressure distribution) but has weak integration of micro-scale data such as borehole-revealed local aquiclude discontinuities. Yet, such micro-scale information is often the direct controlling factor of localized water inrush. Ignoring it diminishes the model’s sensitivity to micro-level risks and constrains the precision of the evaluation.

5. Evaluation Results of Water Inrush Hazard

5.1. Global Evaluation Result

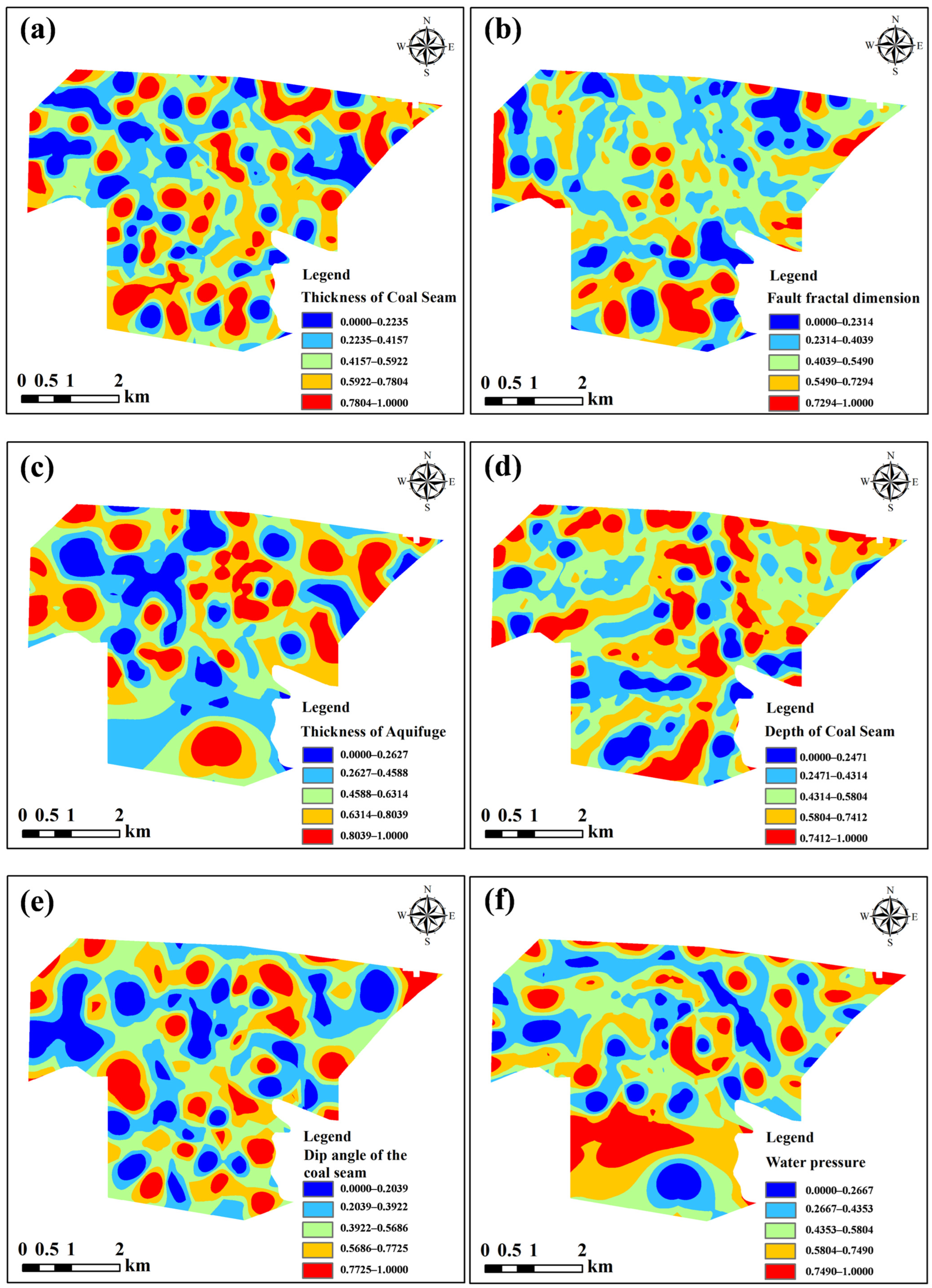

5.1.1. The Overall Standardized Result of the Evaluation Indicators

5.1.2. Global Weight of Evaluation Indicators

5.1.3. Global Evaluation Model

- (1)

- Establishment of the evaluation model

- (2)

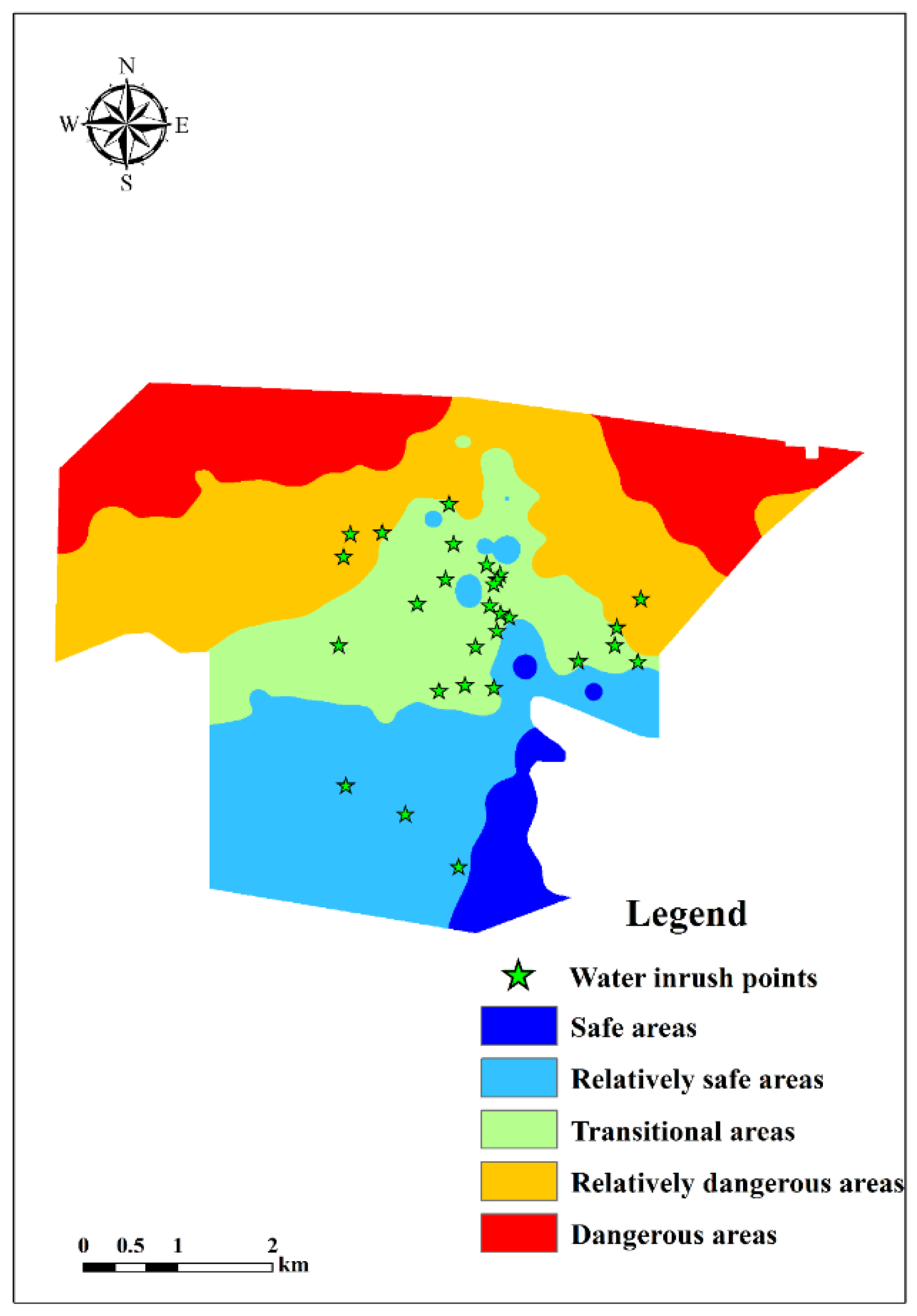

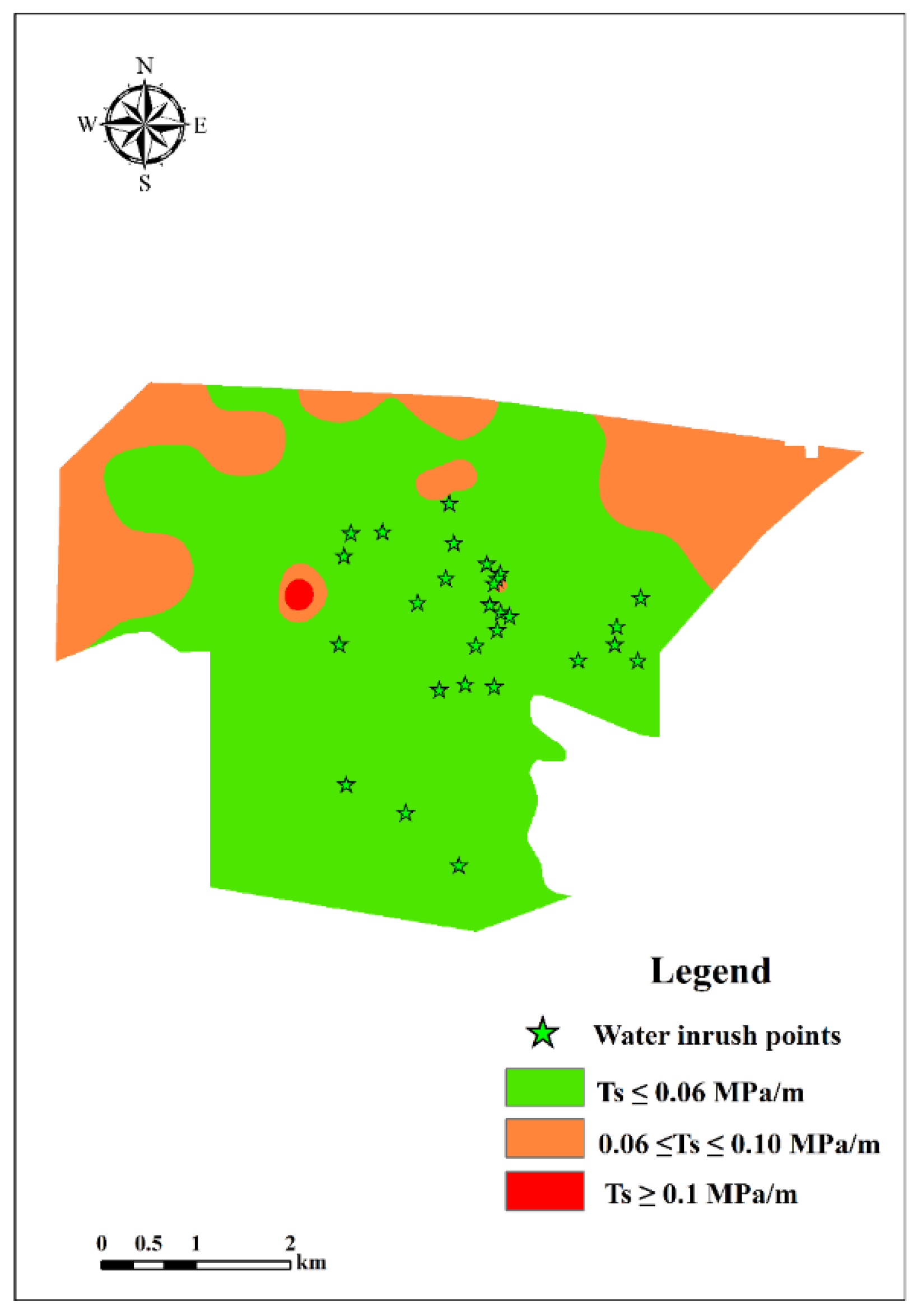

- Evaluation results of floor water inrush risk

5.1.4. Model Validation

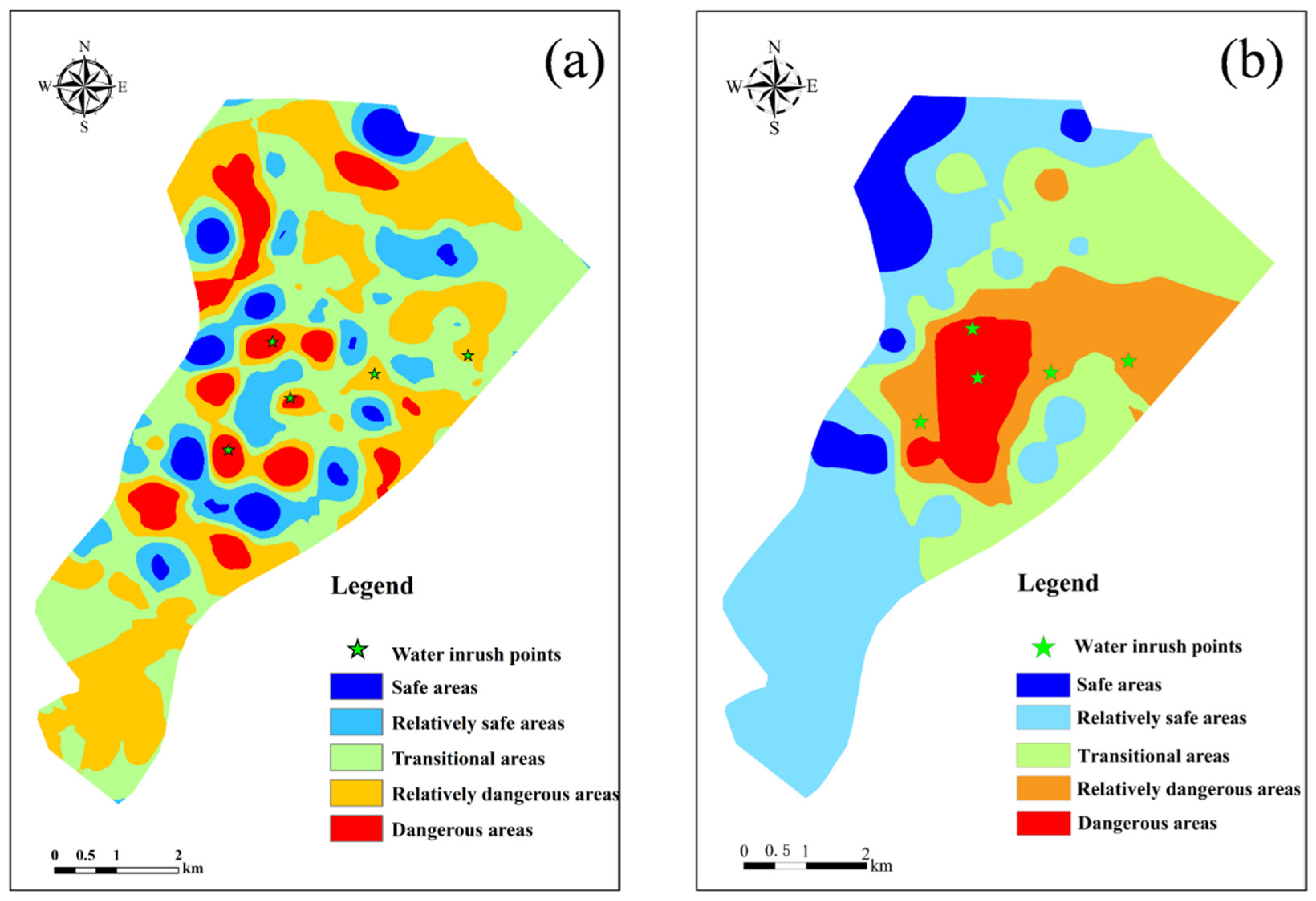

5.2. Local Evaluation Results

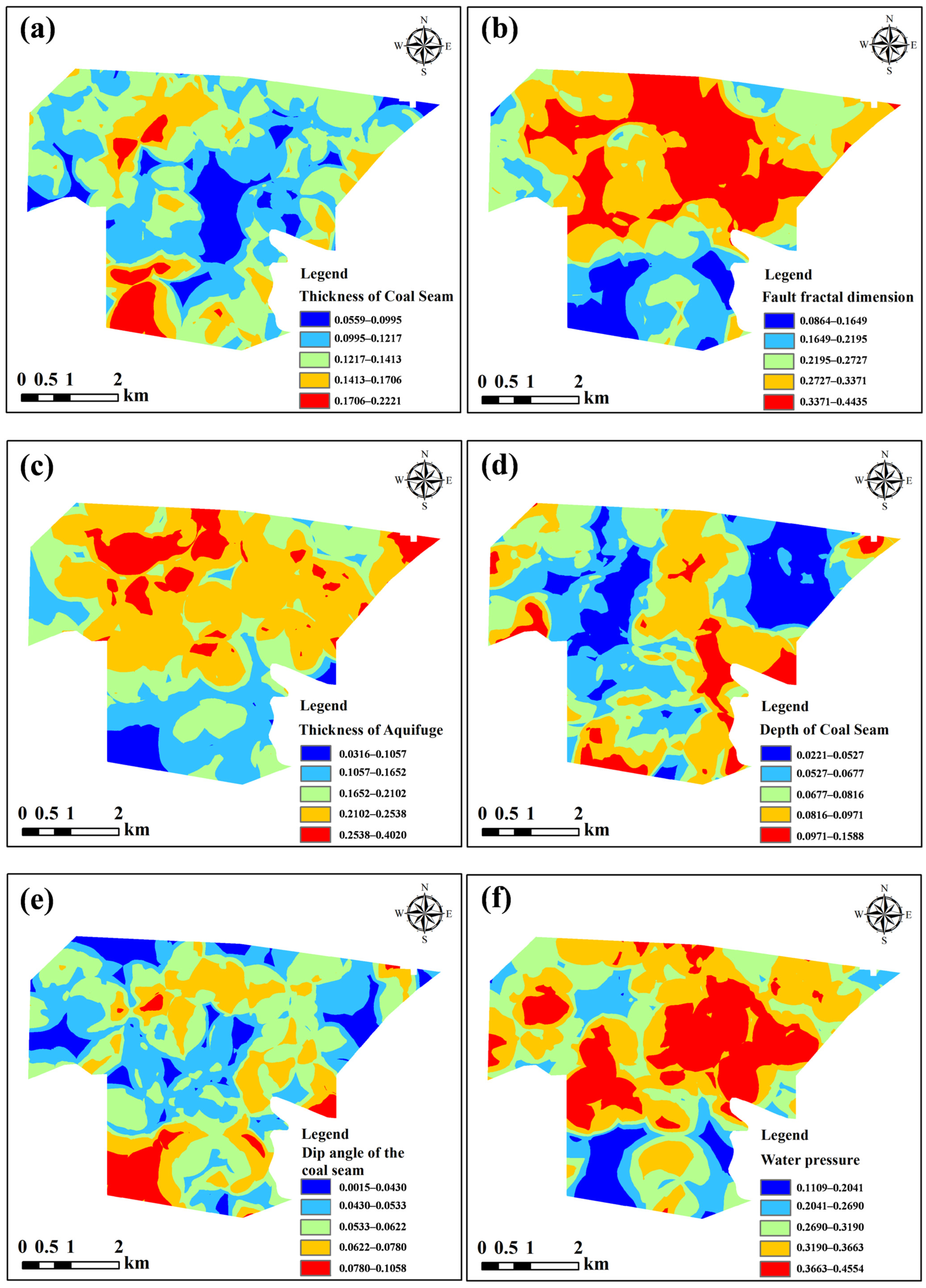

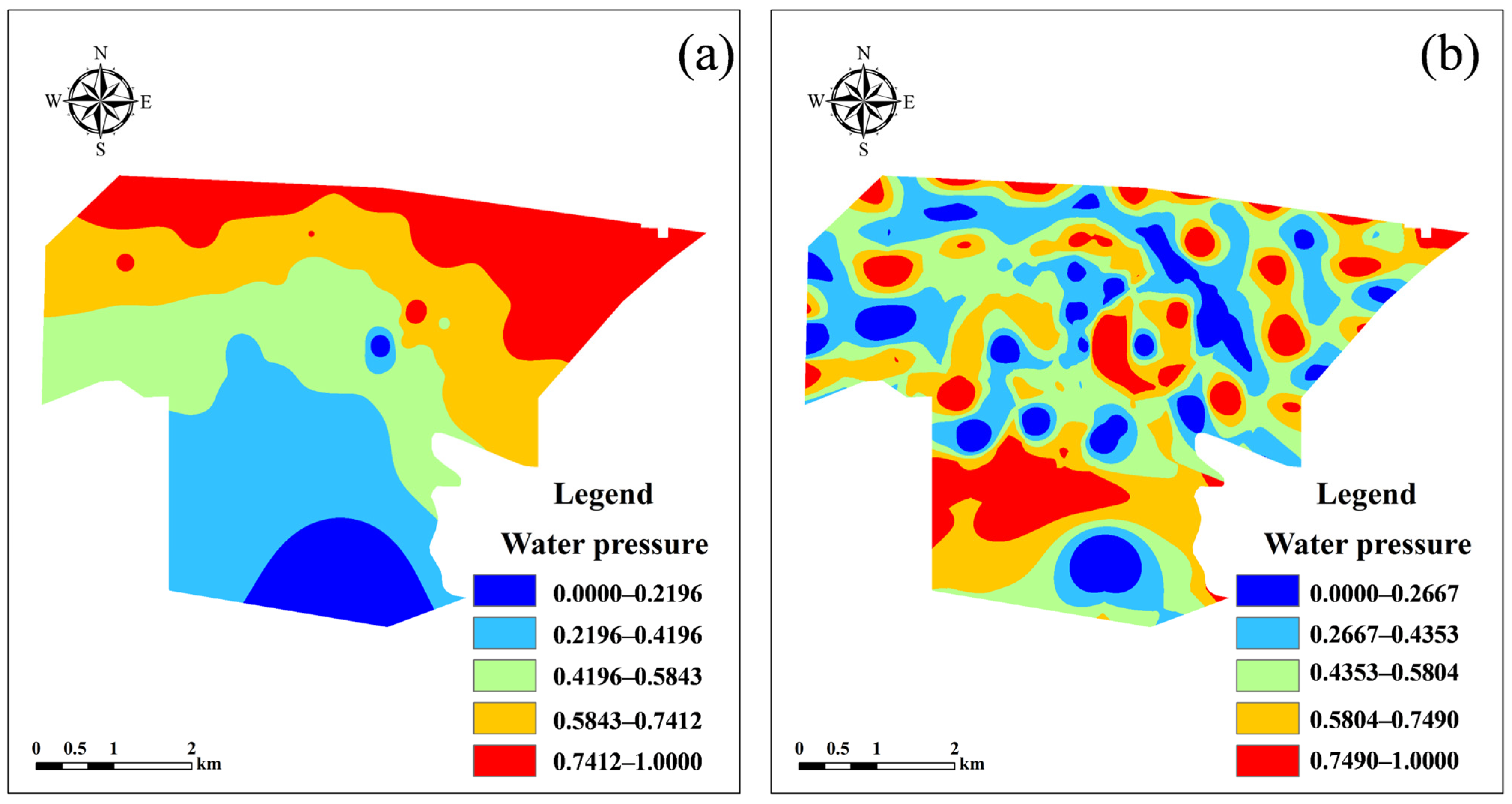

5.2.1. Local Standardization of Evaluation Indicators

5.2.2. Local Weight of Evaluation Indicators

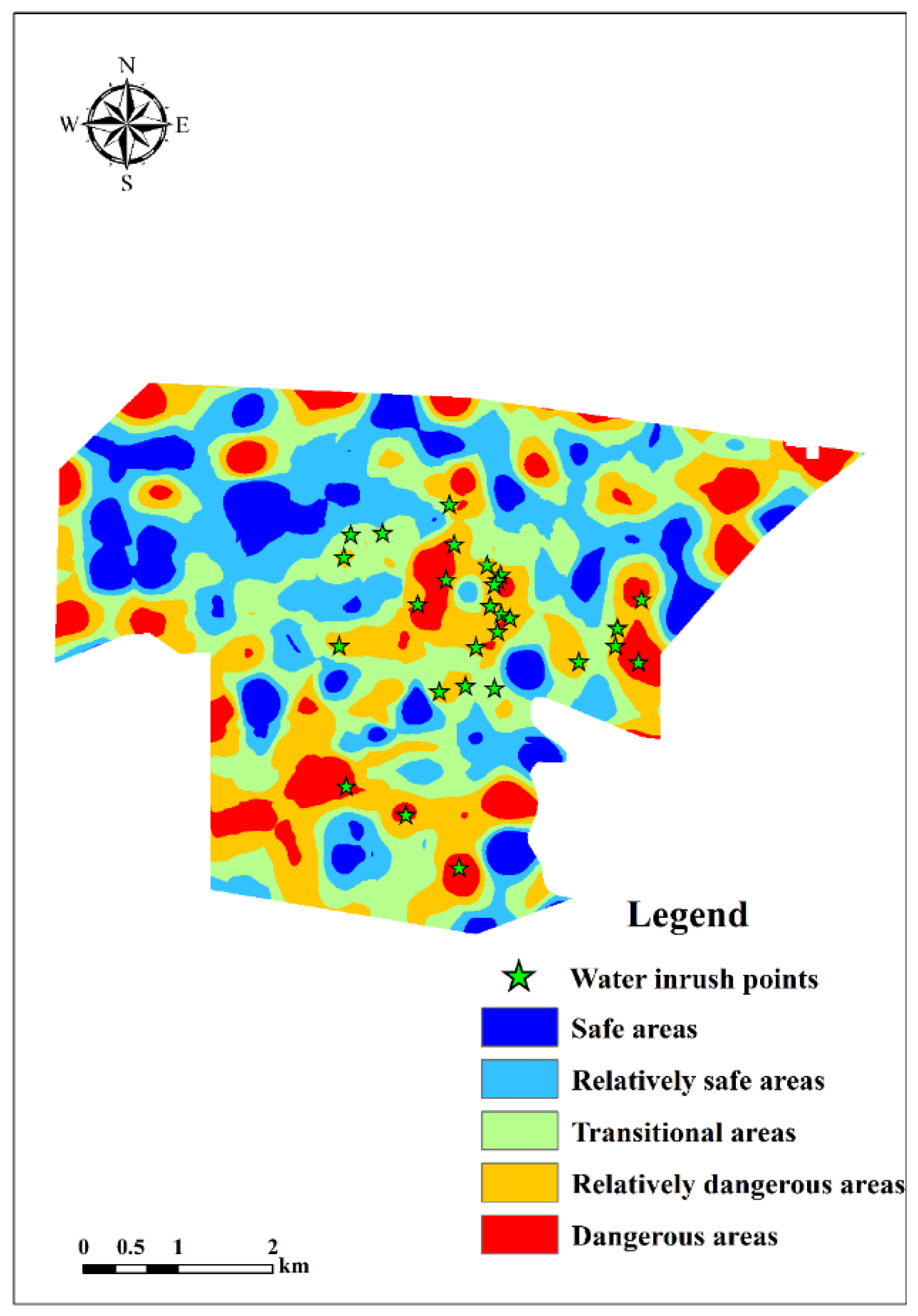

5.2.3. Local Evaluation Model

5.2.4. Model Verification

6. Discussion

6.1. Comparison of the Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Standardized Attribute Values at the Local and Global Levels

6.2. Comparison of the Spatial Distribution Characteristics of the Weights of Local and Global Evaluation Criteria

6.3. Selection of Different Radii for Local Standardization

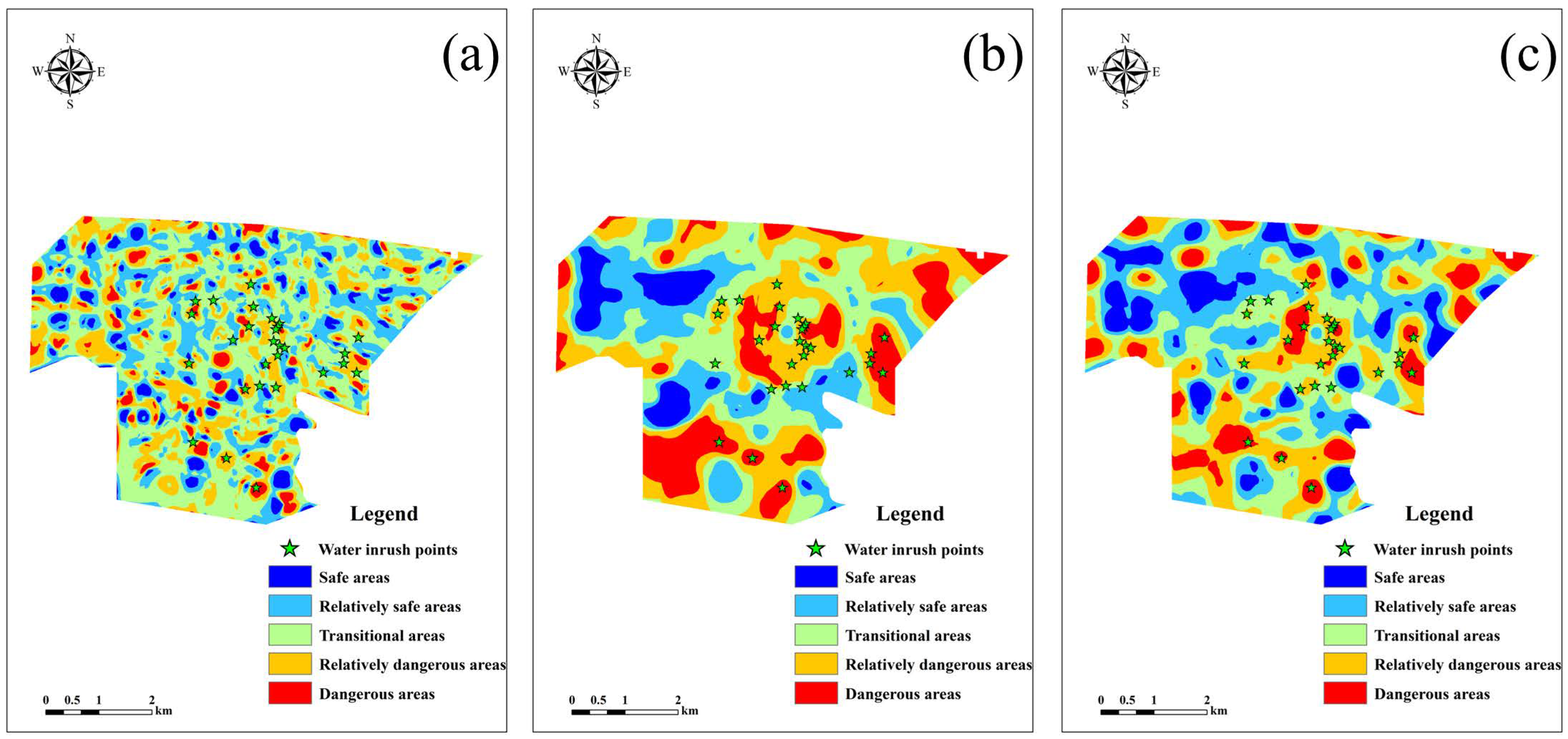

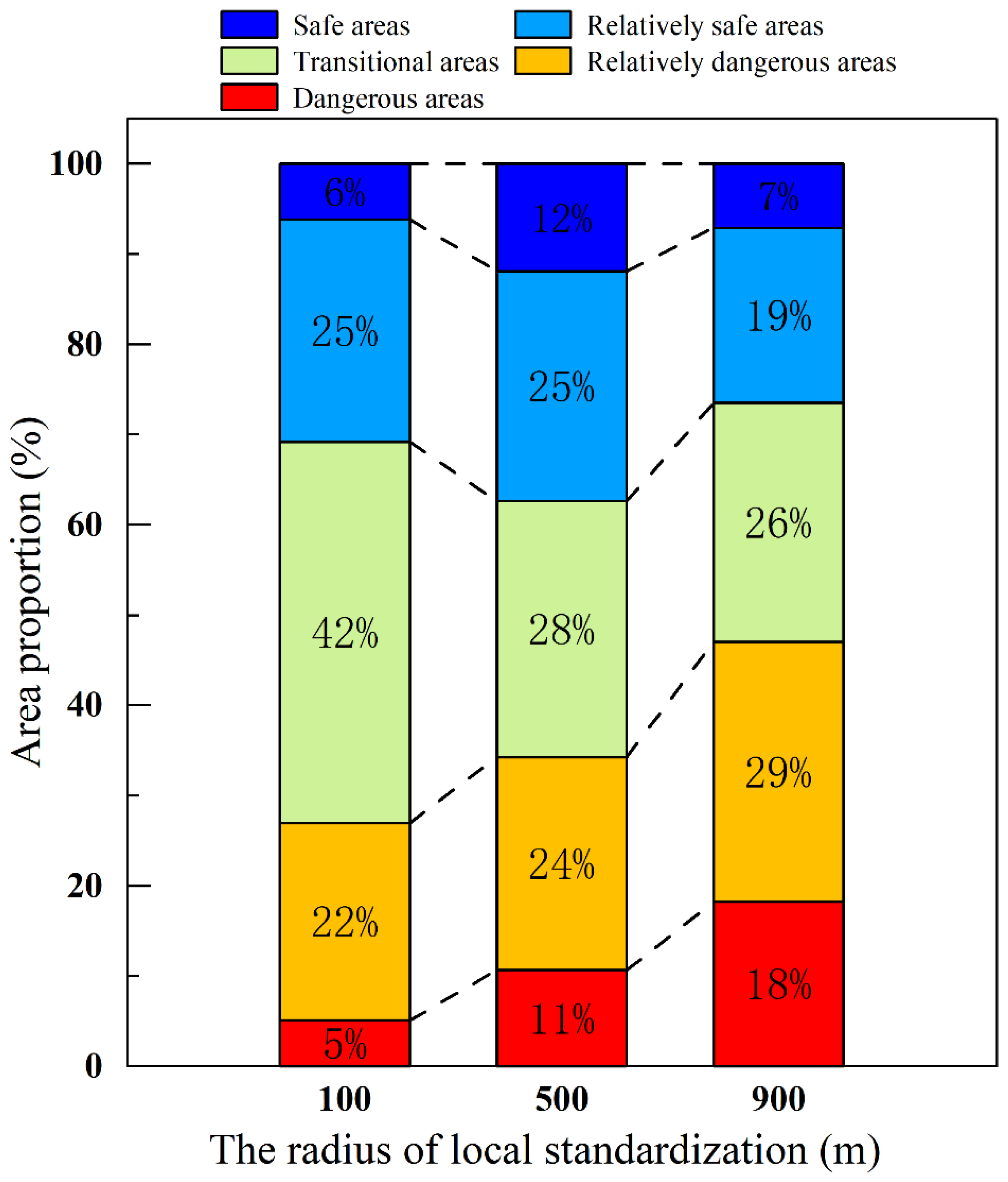

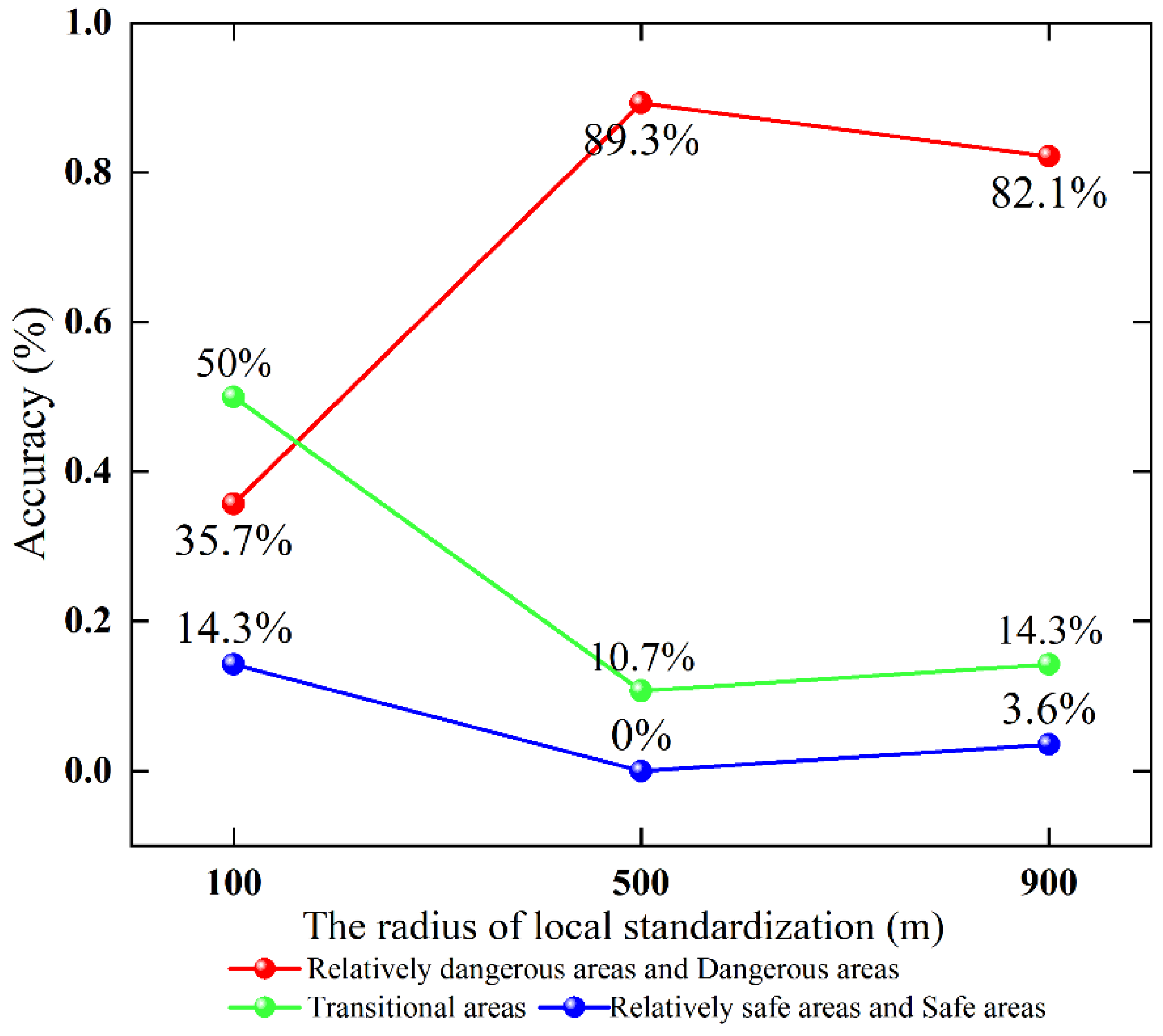

- (1)

- Spatial morphological characteristics

- (2)

- Area statistics comparison

- (3)

- Comparison of identification accuracy of water inrush points

- (1)

- Consistency with the sampling precision and resolution of mine data.

- (2)

- Balancing evaluation accuracy and computational efficiency.

6.4. Comparison of Models

7. More Applications

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study developed a floor water inrush risk assessment method that integrates the Monte Carlo Analytic Hierarchy Process (MAHP) with a moving-window approach. By employing the Beta-PERT probability distribution to characterize uncertainties in expert judgment, the MAHP extends a single judgment matrix into a set of random matrices. This reduces subjective interference, addresses the strong subjectivity and insufficient weight stability inherent in traditional AHP, and ensures that the derived weights better reflect the actual influence of the indicators.

- (2)

- A local evaluation method based on circular moving windows was proposed. Through local standardization and local weight calculation within the window, dynamic spatial adjustment of weights was achieved. This overcomes the limitations of conventional global evaluation methods, which often ignore local variations and rely on fixed weights, thereby yielding results that better align with site-specific geological conditions.

- (3)

- To determine the appropriate radius for local standardization, evaluation results for 100 m, 500 m, and 900 m radii were compared. The findings indicate that a 500 m radius provides the optimal scale for the study area, as it balances overall spatial continuity with local detail, produces a reasonable proportion of safe, transitional, and hazardous zones, and achieves the highest identification accuracy of water inrush points. This radius avoids the excessive fragmentation observed at 100 m and the detail-masking effect of macro trends at 900 m.

- (4)

- Compared with the traditional water-inrush coefficient method and global evaluation models, the proposed method demonstrates significant advantages. Traditional approaches, which rely on a single indicator such as “water pressure/isolating layer thickness,” identified only 3.6% of the 28 water inrush points in the Dongjiahe Coal Mine, failing to capture the combined effects of multiple factors. In contrast, the proposed model integrates six core indicators, and through local standardization and dynamic weight adjustment, increases the identification accuracy of water inrush points to 89.3% with a 500 m radius, while also providing more refined delineation of hazardous zone boundaries.

- (5)

- Cross-mine validation further confirmed the reliability and universality of the method. In its application to the Yangcheng Coal Mine, the method not only maintained high accuracy in identifying water inrush points but also achieved precise delineation of high-risk zones and refinement of hazardous zone boundaries. These outcomes provide a scientific, effective, and targeted technical foundation for mine water prevention and control, enriching and advancing the methodological framework for floor water inrush risk assessment in coal mines.

- (6)

- Although the proposed model performs well in the Dongjiahe and Yangcheng coal mines, its accuracy may decrease in areas lacking sufficient borehole or hydrogeological data. The relationship between mining methods and water inrush risk is also critical: longwall mining in deep coal seams often leads to higher stress concentration and fracture propagation in the floor, thereby increasing the likelihood of hydraulic connection with the underlying aquifers. Future studies should incorporate mining-induced effects and explore adaptive calibration techniques to further extend the applicability of this method to regions with limited data or complex geological conditions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, H.; Xu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhai, P.; Li, X.; Guo, Q.; Wei, Z. Risk Assessment of Water Inrush of a Coal Seam Floor Based on the Combined Empowerment Method. Water 2022, 14, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Mei, T.; Sun, X.; Lv, Y.; Sheng, J.; Cai, M. A study on a water-inrush incident at Laohutai coalmine. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2013, 59, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Meng, F.; Guo, S. Risk analysis of coal seam floor water inrush based on GIS and combined weight TOPSIS method. All Earth 2024, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.S.; Zhao, R.; Cai, M. Safety evaluation of 11# coal seam pressure mining in Sangshuping Coal Mine. Coal Technol. 2018, 4, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Li, W.P.; Zhao, C.X. Water inrush coefficient-unit inflow method for water inrush evaluation of coal mine floor. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2009, 28, 002466–002474. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Sui, W.; Ranville, J.F. Hazard identification and risk assessment of groundwater inrush from a coal mine: A review. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J. Research on water–filled source identification technology of coal seam floor based on multiple index factors. Geofluids 2019, 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Xue, Y. An improved fuzzy comprehensive evaluation system and application for risk assessment of floor water inrush in deep mining. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2019, 37, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Xu, Z.; Lin, P.; Hu, J.; Wang, W. Analysis of factors influencing floor water inrush in coal mines: A nonlinear fuzzy interval assessment method. Mine Water Environ. 2019, 38, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pan, G.; Zhai, J. Analysis on suitability of water prevention and control measures with water pumping and pressure eleasing in underground mine. Coal Sci. Technol. 2012, 40, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, M.; Shi, L.; Teng, C.; Zhou, Y. Assessment of water inrush risk using the fuzzy Delphi analytic hierarchy process and grey relational analysis in the Liangzhuang Coal Mine, China. Mine Water Environ. 2017, 36, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Luo, L.; Liu, S.; Sun, W.; Zeng, Y. Quantitative Evaluation and Prediction of Water Inrush Vulnerability from Aquifers Overlying Coal Seams in Donghuantuo Coal Mine, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 74, 1429–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, W.; Zeng, Y. Assessment of Groundwater Inrush from Underlying Aquifers in Tunbai Coal Mine, Shanxi Province, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Xu, H.; Pang, W. GIS and ANN Coupling Model: An Innovative Approach to Evaluate Vulnerability of Karst Water Inrush in Coalmines of North China. Environ. Geol. 2007, 54, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Wang, J.; Xie, S. Prediction of Groundwater Inrush into Coal Mines from Aquifers Underlying the Coal Seams in China: Application of Vulnerability Index Method to Zhangcun Coal Mine, China. Environ. Geol. 2008, 57, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z. Evaluation of water inrush risk from coal seam floors with an AHP–EWM algorithm and GIS. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Wei, J.; Yin, H.; Xie, D.; Zhang, W. An improved model to predict the water-inrush risk from an Ordovician limestone aquifer under coal seams: A case study of the Longgu coal mine in China. Carbonates Evaporites 2020, 35, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Mu, W.; Du, Y.; Tu, K. Integrating the hierarchy-variable-weight model with collaboration-competition theory for assessing coal-floor water-inrush risk. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Sui, W. Risk evaluation of mine-water inrush based on principal component logistic regression analysis and an improved analytic hierarchy process. Hydrogeol. J. 2021, 29, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, K.; Deng, G.; Li, J.; Jie, B. A Multifactor Quantitative Assessment Model for Safe Mining after Roof Drainage in the Liangshuijing Coal Mine. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 26437–26454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, W. Risk Assessment of Water Inrush from Coal Seam Roof Based on the Combined Weighting of the Geographic Information System and Game Theory: A Case Study of Dananhu Coal Mine No. 7, China. Water 2024, 16, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhai, Y. Application of artificial neural network technology to predicting small faults and folds in coal seams, China. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 2, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Z. Identification of Mine Water Inrush Source Based on PCA-FDA: Xiandewang Coal Mine Case. Geofluids 2020, 2020, 2584094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, S.; Shi, K. Risk assessment of coal mine water inrush based on PCA-DBN. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, L. A novel dynamic predictive method of water inrush from coal floor based on gated recurrent unit model. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 2027–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.P.; Wang, C.L.; Wang, X.D. Coal mine floor water inrush prediction based on CNN neural network. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard. Control 2021, 1, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Wang, Z. Dynamic prediction of water inrush from seam floor based on gate recurrent unit neural network model. J. Taiyuan Univ. Technol. 2021, 5, 810–816. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadirianniari, S.; McDougall, S.; Eberhardt, E.; Varian, J.; Llewelyn, K.; Campbell, R.; Moss, A. Wet inrush susceptibility assessment at the Deep Ore Zone mine using a random forest machine learning model. Min. Technol. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. 2024, 133, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.T.; Liu, Y.J.; Shen, J.J. Safety evaluation of floor water inrush in deep mining based on fuzzy matter-element theory. J. Shandong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 33, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Niu, P.K.; Gong, H.J.; Liu, S.Q.; Zeng, Y.F. Applicability analysis of AHP and ANN vulnerability index based on GIS in coal floor water inrush evaluation. J. Min. Strat. Control Eng. 2018, 23, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wang, D.; Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Fang, Y. Local Water Inrush Risk Assessment Method Based on Moving Window and Its Application in the Liangshuijing Mining Area. Water 2024, 16, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Teng, C.; Li, C.S.; Wang, D.D. Huaheng minefield fault quantification and its influence on floor limestone water inrush, China. Coal Mine Saf. 2015, 46, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yi, S.; Xiao, Y. Assessment of flood susceptible areas using spatially explicit, probabilistic multi-criteria decision analysis. J. Hydrol. 2018, 558, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yi, S.; Tang, Z. A Spatially Explicit Multi-Criteria Analysis Method on Solving Spatial Heterogeneity Problems for Flood Hazard Assessment. Water Resour. Manag. 2018, 32, 3317–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Borehole | Fault Fractal Dimension | Coal Seam Dip Angle (°) | Water Pressure (MPa) | Aquiclude Thickness (m) | Coal Seam Thickness (m) | Coal Seam Burial Depth (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | 0.417 | 6.1 | 0.30 | 30.00 | 3.15 | 319.47 |

| 2 | 39 | 0.458 | 3.2 | 1.41 | 47.00 | 2.59 | 338.07 |

| 3 | 117 | 0.412 | 8.7 | 0.16 | 16.00 | 3.73 | 298.41 |

| 4 | 118 | 0.568 | 10.3 | 0.34 | 34.00 | 4.09 | 318.34 |

| 5 | 123 | 0.717 | 15.4 | 0.24 | 24.00 | 4.03 | 301.61 |

| 6 | 129 | 0.717 | 16.3 | 0.26 | 26.00 | 2.09 | 250.95 |

| 7 | 131 | 0.525 | 4.5 | 0.93 | 31.00 | 3.36 | 375.18 |

| 9 | 201 | 0.591 | 7.3 | 0.34 | 34.00 | 3.84 | 322.07 |

| 10 | 203 | 0.462 | 11.4 | 0.62 | 31.00 | 3.62 | 363.23 |

| 11 | 204 | 0.652 | 14.8 | 0.20 | 20.00 | 1.51 | 299.24 |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … |

| 117 | XB52 | 0.349 | 5.9 | 1.91 | 27.29 | 3.55 | 487.15 |

| 118 | XB53 | 0.339 | 13.0 | 2.07 | 23.00 | 2.35 | 525.15 |

| 119 | XB54 | 0.340 | 10.6 | 2.28 | 32.57 | 2.60 | 536.45 |

| 120 | XB55 | 0.341 | 15.3 | 2.28 | 28.50 | 3.80 | 531.95 |

| 121 | XB56 | 0.346 | 14.8 | 2.19 | 31.29 | 3.45 | 513.75 |

| 122 | XB57 | 0.373 | 13.1 | 1.99 | 33.17 | 3.50 | 495.15 |

| 123 | XB58 | 0.322 | 7.9 | 2.41 | 30.13 | 3.25 | 552.05 |

| 124 | XB59 | 0.332 | 9.4 | 2.33 | 25.89 | 2.95 | 558.00 |

| 125 | XB60 | 0.339 | 10.4 | 2.10 | 23.33 | 2.50 | 534.05 |

| 126 | XB61 | 0.361 | 11.6 | 1.64 | 27.33 | 0.60 | 477.85 |

| 127 | XB62 | 0.348 | 6.7 | 1.92 | 19.20 | 2.35 | 524.90 |

| Indicators | Aquiclude Thickness | Coal Seam Thickness | Fault Control Index | Burial Depth | Dip Angle | Water Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wai | 0.10237 | 0.064401 | 0.061851 | 0.63466 | 0.073174 | 0.063541 |

| Risk Zones | Safe Areas | Relatively Safe Areas | Transitional Areas | Relatively Dangerous Areas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Inrush Points | |||||

| Number of Water Inrush Points (n) | 0 | 3 | 19 | 6 | |

| Proportion (%) | 0 | 10.7 | 67.9 | 21.4 | |

| Risk Zones | Safe Areas | Relatively Safe Areas | Transitional Areas | Relatively Dangerous Areas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Inrush Points | |||||

| Number of Water Inrush Points (n) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 18 | |

| Proportion (%) | 0 | 0 | 10.7 | 54.3 | |

| Radius of Local Standardization (m) | 100 | 500 | 900 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area of Risk Zones (km2) | ||||

| Safe areas | 1.822 | 3.517 | 2.094 | |

| Relatively safe areas | 7.305 | 7.552 | 5.751 | |

| Transitional areas | 12.497 | 8.407 | 7.846 | |

| Relatively dangerous areas | 6.490 | 6.988 | 8.527 | |

| Dangerous areas | 1.507 | 3.157 | 5.402 | |

| Radius of Local Standardization (m) | 100 | 500 | 900 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Water Inrush Points | ||||

| Safe and relatively safe zones | 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| Transitional zone | 14 | 3 | 4 | |

| Dangerous and relatively dangerous zones | 10 | 25 | 23 | |

| Total | 28 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Si, X.; Wang, D.; Gao, C.; Ma, J.; Xu, W.; Zhu, Z. A Moving-Window Based Method for Floor Water Inrush Risk Assessment in Coal Mines. Water 2025, 17, 3277. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223277

Si X, Wang D, Gao C, Ma J, Xu W, Zhu Z. A Moving-Window Based Method for Floor Water Inrush Risk Assessment in Coal Mines. Water. 2025; 17(22):3277. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223277

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Xiang, Dangliang Wang, Chengyue Gao, Jin Ma, Weizhuo Xu, and Zhiheng Zhu. 2025. "A Moving-Window Based Method for Floor Water Inrush Risk Assessment in Coal Mines" Water 17, no. 22: 3277. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223277

APA StyleSi, X., Wang, D., Gao, C., Ma, J., Xu, W., & Zhu, Z. (2025). A Moving-Window Based Method for Floor Water Inrush Risk Assessment in Coal Mines. Water, 17(22), 3277. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223277