Impact of Wastewater Treatment Plant Discharge on Water Quality of a Heavily Urbanized River in Milan Metropolitan Area: Traditional and Emerging Contaminant Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

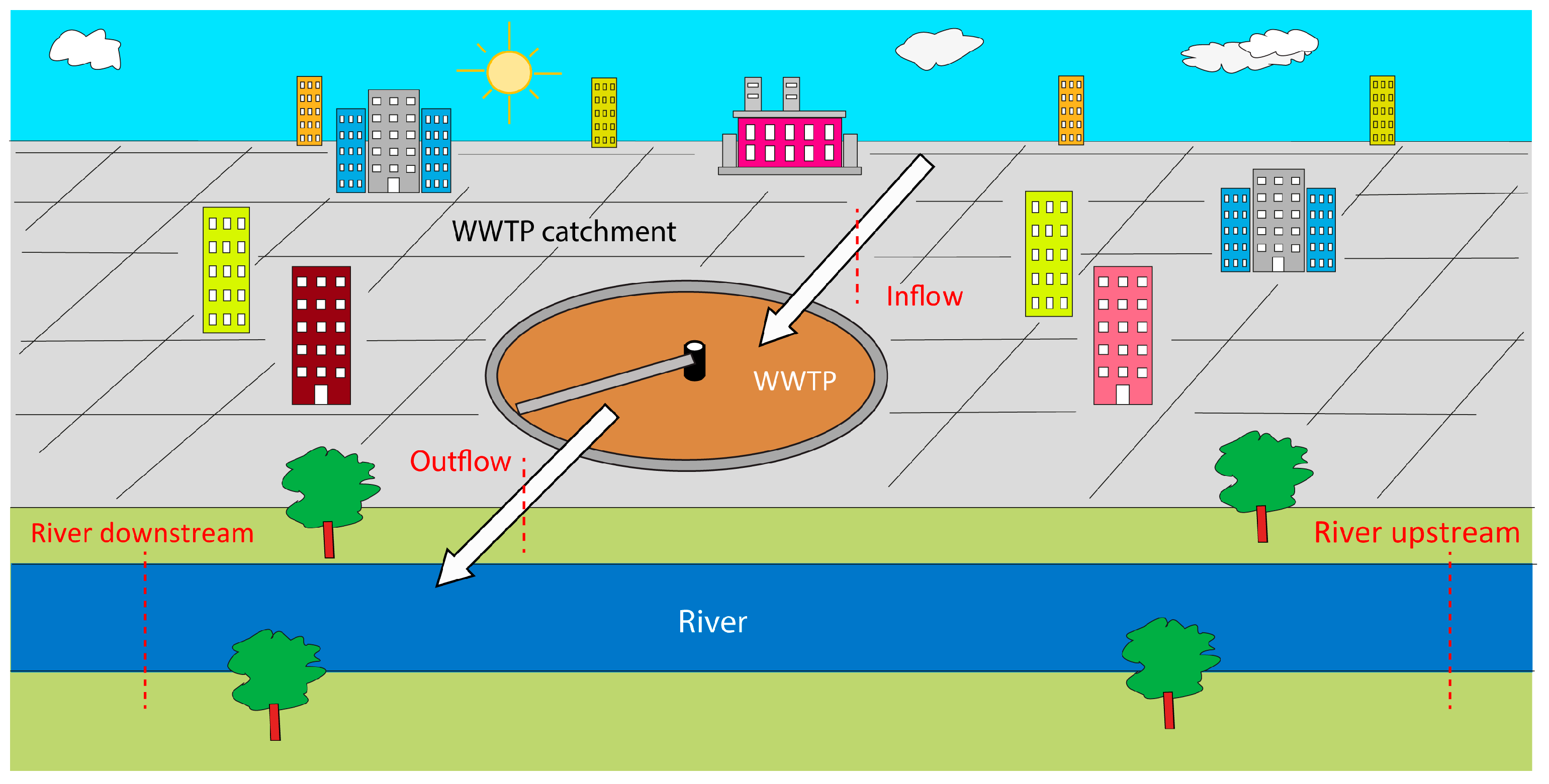

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Samplings and Physical–Chemical Characterization

2.3. Selected Compounds and Analytical Methods

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Occurrence of Pollutants in the WWTP and in the River

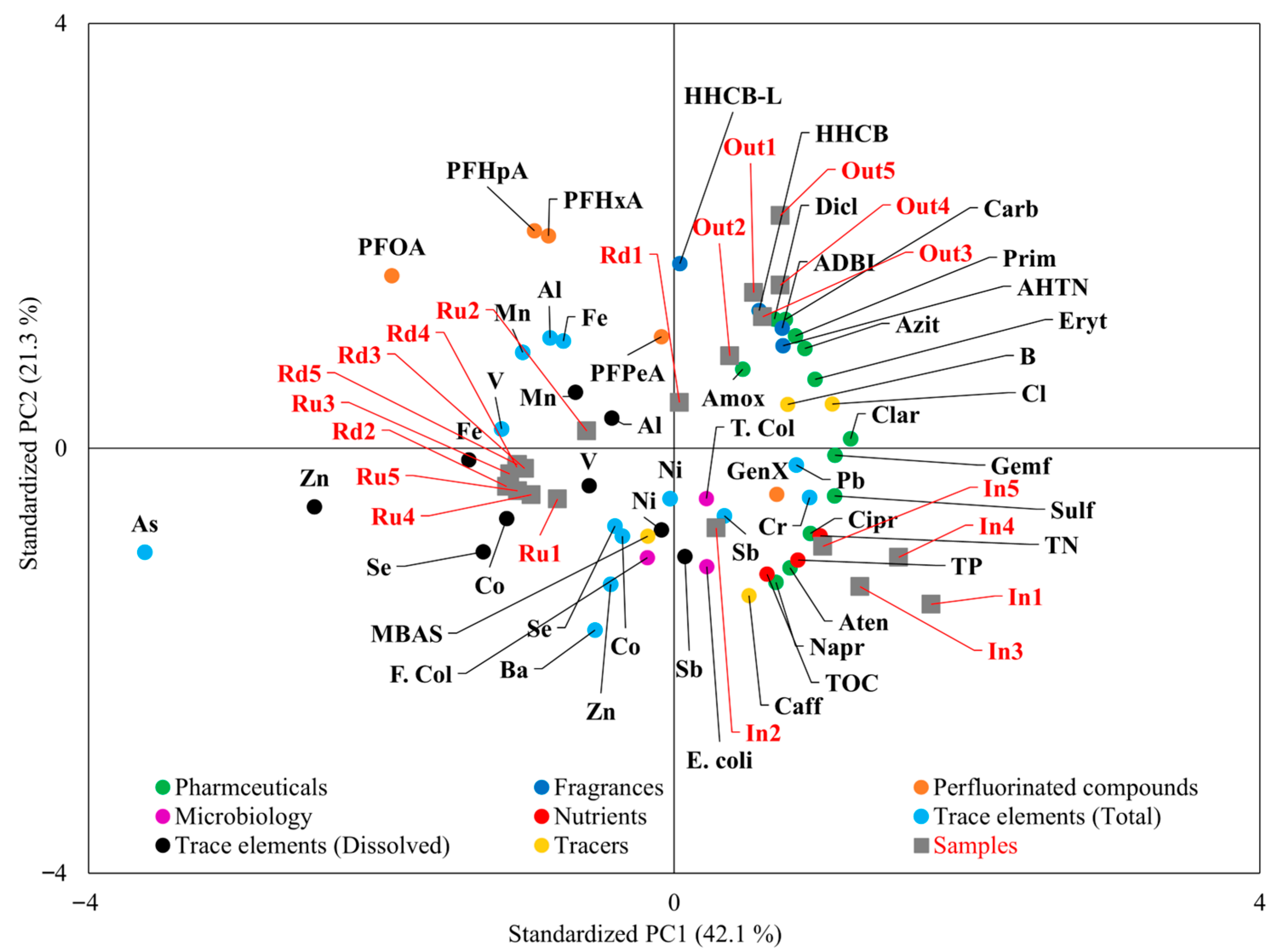

3.2. Contamination Pattern in Different Water Samples: PCA and Correlation Analysis

3.3. WWTP Removal Efficiency for Emerging Compounds

3.4. Preliminary Ecological Risk Assessment of Emerging Organic Contaminants in River Waters

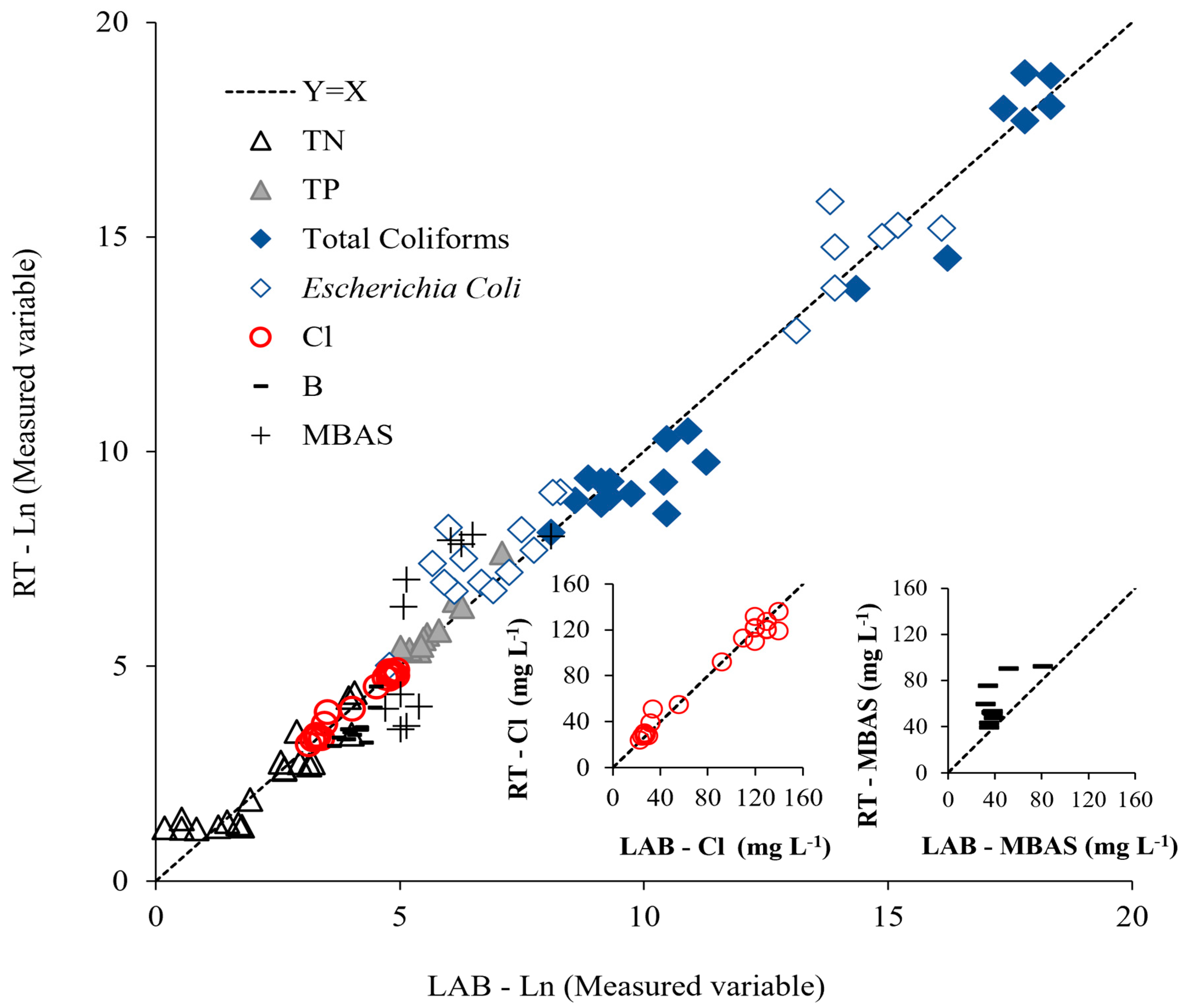

3.5. Comparison Between Laboratory and Real-Time Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jahanger, A.; Usman, M.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. The Linkages between Natural Resources, Human Capital, Globalization, Economic Growth, Financial Development, and Ecological Footprint: The Moderating Role of Technological Innovations. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.H.; de Oliveira, J.A.P. Pollution and Economic Development: An Empirical Research Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 123003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainurin, S.N.; Wan Ismail, W.Z.; Mahamud, S.N.I.; Ismail, I.; Jamaludin, J.; Ariffin, K.N.Z.; Wan Ahmad Kamil, W.M. Advancements in Monitoring Water Quality Based on Various Sensing Methods: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zheng, T.; Li, M.; Liu, X. Organic Contaminants in the Effluent of Chinese Wastewater Treatment Plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 26852–26860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aib, H.; Czegeny, I.; Benhizia, R.; Czédli, H.M. Evaluating the Efficiency of Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Northern Hungarian Plains Using Physicochemical and Microbiological Parameters. Water 2024, 16, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.H.; Nghiem, L.D.; Hai, F.I.; Zhang, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.C. A Review on the Occurrence of Micropollutants in the Aquatic Environment and Their Fate and Removal during Wastewater Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 473–474, 619–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derco, J.; Žgajnar Gotvajn, A.; Guľašová, P.; Šoltýsová, N.; Kassai, A. Selected Micropollutant Removal from Municipal Wastewater. Processes 2024, 12, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, V.; Gasparini Fernandes Cunha, D.; Rath, S. Adsorption of Recalcitrant Contaminants of Emerging Concern onto Activated Carbon: A Laboratory and Pilot-Scale Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgin, M.; Beck, B.; Boehler, M.; Borowska, E.; Fleiner, J.; Salhi, E.; Teichler, R.; von Gunten, U.; Siegrist, H.; McArdell, C.S. Evaluation of a Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plant Upgraded with Ozonation and Biological Post-Treatments: Abatement of Micropollutants, Formation of Transformation Products and Oxidation by-Products. Water Res. 2018, 129, 486–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, I.T.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Miller, M.; Ng, C.A.; Patton, S.; Scheringer, M.; Trier, X.; Vierke, L.; et al. The Concept of Essential Use for Determining When Uses of PFASs Can Be Phased Out. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2019, 21, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademollo, N.; Spataro, F.; Rauseo, J.; Pescatore, T.; Fattorini, N.; Valsecchi, S.; Polesello, S.; Patrolecco, L. Occurrence, Distribution and Pollution Pattern of Legacy and Emerging Organic Pollutants in Surface Water of the Kongsfjorden (Svalbard, Norway): Environmental Contamination, Seasonal Trend and Climate Change. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 163, 111900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valsecchi, S.; Babut, M.; Mazzoni, M.; Pascariello, S.; Ferrario, C.; De Felice, B.; Bettinetti, R.; Veyrand, B.; Marchand, P.; Polesello, S. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Fish from European Lakes: Current Contamination Status, Sources, and Perspectives for Monitoring. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 658–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Choi, K.; Park, K.; Seong, C.; Yu, S.D.; Kim, P. Adverse Effects of Perfluoroalkyl Acids on Fish and Other Aquatic Organisms: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobelius, L.; Glimstedt, L.; Olsson, J.; Wiberg, K.; Ahrens, L. Mass Flow of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in a Swedish Municipal Wastewater Network and Wastewater Treatment Plant. Chemosphere 2023, 336, 139182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Zambello, E. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Untreated and Treated Sewage Sludge: Occurrence and Environmental Risk in the Case of Application on Soil—A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 538, 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Geißen, S.-U.; Gal, C. Carbamazepine and Diclofenac: Removal in Wastewater Treatment Plants and Occurrence in Water Bodies. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambaza, S.S.; Naicker, N. Contribution of Wastewater to Antimicrobial Resistance: A Review Article. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2023, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara, M.; Gans, O.; Windhofer, G.; Krenn, U.; Hartl, W.; Braun, K.; Scharf, S.; Scheffknecht, C. Occurrence of Polycyclic Musks in Wastewater and Receiving Water Bodies and Fate during Wastewater Treatment. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasselli, S.; Rogora, M.; Orrù, A.; Guzzella, L. Behaviour of Synthetic Musk Fragrances in Freshwaters: Occurrence, Relations with Environmental Parameters, and Preliminary Risk Assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 109643–109658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Shi, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, M. Determination of Synthetic Musks in Sediments of Yellow River Delta Wetland, China. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 97, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonards, P.E.G.; de Boer, J. Synthetic Musks in Fish and Other Aquatic Organisms. In Series Anthropogenic Compounds: Synthetic Musk Fragances in the Environment; Rimkus, G.G., Ed.; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 49–84. ISBN 978-3-540-47900-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tasselli, S.; Valenti, E.; Guzzella, L. Polycyclic Musk Fragrance (PMF) Removal, Adsorption and Biodegradation in a Conventional Activated Sludge Wastewater Treatment Plant in Northern Italy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 38054–38064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-L.; Yao, L. Fragrances in Surface Waters; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tumová, J.; Šauer, P.; Golovko, O.; Koba Ucun, O.; Grabic, R.; Máchová, J.; Kocour Kroupová, H. Effect of Polycyclic Musk Compounds on Aquatic Organisms: A Critical Literature Review Supplemented by Own Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2235–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, B.; Dolu, T.; Koyuncu, S. Behavior and Removal of Ciprofloxacin and Sulfamethoxazole Antibiotics in Three Different Types of Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Comparative Study. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2000/60/EC; Directive 2000/60/EC of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. European Parliament and Council of the European Union: Strasbourg, France, 2000; pp. 1–73.

- 2008/105/EC; Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2015/495 of 20 March 2015 establishing a watch list of substances for Union-wide monitoring in the field of water policy pursuant to Directive 2008/105/EC. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; pp. 40–42.

- 2008/105/EC; Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2018/840 of 5 June 2018 establishing a watch list of substances for Union-wide monitoring in the field of water policy pursuant to Directive 2008/105/EC. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 9–12.

- 2008/105/EC; Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/1161 of 4 August 2020 establishing a watch list of substances for Union-wide monitoring in the field of water policy pursuant to Directive 2008/105/EC. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; pp. 32–35.

- 2008/105/EC; Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2022/1307 of 22 July 2022 establishing a watch list of substances for Union-wide monitoring in the field of water policy pursuant to Directive 2008/105/EC. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; pp. 117–120.

- Azevedo, L.S.; Pestana, I.A.; Rocha, A.R.M.; Meneguelli-Souza, A.C.; Lima, C.A.I.; Almeida, M.G.; Bastos, W.R.; Souza, C.M.M. Drought Promotes Increases in Total Mercury and Methylmercury Concentrations in Fish from the Lower Paraíba Do Sul River, Southeastern Brazil. Chemosphere 2018, 202, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmen, A.; Lemos, P.C.; Carvalho, G.; Yuan, Z.; Keller, J.; Blackall, L.L.; Reis, M.A.M. Advances in Enhanced Biological Phosphorus Removal: From Micro to Macro Scale. Water Res. 2007, 41, 2271–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copetti, D.; Marziali, L.; Viviano, G.; Valsecchi, L.; Guzzella, L.; Capodaglio, A.G.; Tartari, G.; Polesello, S.; Valsecchi, S.; Mezzanotte, V.; et al. Intensive Monitoring of Conventional and Surrogate Quality Parameters in a Highly Urbanized River Affected by Multiple Combined Sewer Overflows. Water Supply 2018, 19, 953–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copetti, D.; Tartari, G.; Valsecchi, L.; Salerno, F.; Viviano, G.; Mastroianni, D.; Yin, H.; Viganò, L. Phosphorus Content in a Deep River Sediment Core as a Tracer of Long-Term (1962–2011) Anthropogenic Impacts: A Lesson from the Milan Metropolitan Area. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 646, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collivignarelli, M.C.; Abbà, A.; Benigna, I.; Sorlini, S.; Torretta, V. Overview of the Main Disinfection Processes for Wastewater and Drinking Water Treatment Plants. Sustainability 2018, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Wang, Q. Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Wastewaters: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, G.E. Occurrence and Removal of Metals in Urban Wastewater Treatment Plants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, G.; Nodehi, R.N.; Alimohammadi, M.; Rezaei Kahkah, M.R.; Mahvi, A.H. Monitoring of Caffeine Concentration in Infused Tea, Human Urine, Domestic Wastewater and Different Water Resources in Southeast of Iran- Caffeine an Alternative Indicator for Contamination of Human Origin. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 283, 111971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sérodes, J.-B.; Behmel, S.; Simard, S.; Laflamme, O.; Grondin, A.; Beaulieu, C.; Proulx, F.; Rodriguez, M.J. Tracking Domestic Wastewater and Road De-Icing Salt in a Municipal Drinking Water Reservoir: Acesulfame and Chloride as Co-Tracers. Water Res. 2021, 203, 117493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviano, G.; Salerno, F.; Manfredi, E.C.; Polesello, S.; Valsecchi, S.; Tartari, G. Surrogate Measures for Providing High Frequency Estimates of Total Phosphorus Concentrations in Urban Watersheds. Water Res. 2014, 64, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, M.G.; Katz, D.R.; Sullivan, J.C.; Shapley, D.; Lipscomb, J.; Epstein, J.; Juhl, A.R.; Knudson, C.; O’Mullan, G.D. Spatial Patterns of Pharmaceuticals and Wastewater Tracers in the Hudson River Estuary. Water Res. 2018, 137, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corada-Fernández, C.; Lara-Martín, P.A.; Candela, L.; González-Mazo, E. Tracking Sewage Derived Contamination in Riverine Settings by Analysis of Synthetic Surfactants. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinoiseau, D.; Louvat, P.; Paris, G.; Chen, J.-B.; Chetelat, B.; Rocher, V.; Guérin, S.; Gaillardet, J. Are Boron Isotopes a Reliable Tracer of Anthropogenic Inputs to Rivers over Time? Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.F.; Lee, K.P.; Chieng, H.J.; Ramli, I.I.S.B. Removal of Boron from Ceramic Industry Wastewater by Adsorption–Flocculation Mechanism Using Palm Oil Mill Boiler (POMB) Bottom Ash and Polymer. Water Res. 2009, 43, 3326–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaroshenko, I.; Kirsanov, D.; Marjanovic, M.; Lieberzeit, P.A.; Korostynska, O.; Mason, A.; Frau, I.; Legin, A. Real-Time Water Quality Monitoring with Chemical Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Cai, S.; Jiang, D.; Liu, J. A Data-Driven Model for Real-Time Water Quality Prediction and Early Warning by an Integration Method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 30374–30385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillman, E.F. Evaluation of the Eureka Manta2 Water-Quality Multiprobe Sonde; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2017.

- Lohmann, R.; Vrana, B.; Muir, D.; Smedes, F.; Sobotka, J.; Zeng, E.Y.; Bao, L.-J.; Allan, I.J.; Astrahan, P.; Barra, R.O.; et al. Passive-Sampler-Derived PCB and OCP Concentrations in the Waters of the World─First Results from the AQUA-GAPS/MONET Network. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9342–9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasselli, S.; Guzzella, L. Polycyclic Musk Fragrances (PMFs) in Wastewater and Activated Sludge: Analytical Protocol and Application to a Real Case Study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 30977–30986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copetti, D.; Valsecchi, L.; Capodaglio, A.G.; Tartari, G. Direct Measurement of Nutrient Concentrations in Freshwaters with a Miniaturized Analytical Probe: Evaluation and Validation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, A.J.; Palmer-Felgate, E.J.; Halliday, S.J.; Skeffington, R.A.; Loewenthal, M.; Jarvie, H.P.; Bowes, M.J.; Greenway, G.M.; Haswell, S.J.; Bell, I.M.; et al. Hydrochemical Processes in Lowland Rivers: Insights from in Situ, High-Resolution Monitoring. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 4323–4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahady, T.D.; Cleary, W.C. Influence of a Low-Head Dam on Water Quality of an Urban River System. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.; Hothorn, T. An Introduction to Applied Multivariate Analysis with R; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-9650-3. [Google Scholar]

- Helsel, D.R.; Hirsch, R.M.; Ryberg, K.R.; Archfield, S.A.; Gilroy, E.J. Statistical Methods in Water Resources; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2020.

- Evans, J.D. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.: Belmont, CA, USA, 1996; p. xxii, 600. ISBN 978-0-534-23100-2. [Google Scholar]

- Badawy, M.I.; El-Gohary, F.A.; Abdel-Wahed, M.S.; Gad-Allah, T.A.; Ali, M.E.M. Mass Flow and Consumption Calculations of Pharmaceuticals in Sewage Treatment Plant with Emphasis on the Fate and Risk Quotient Assessment. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Bolaña, C.; Pérez-Parada, A.; Niell, S.; Heinzen, H.; de Mello, F.T. Comparative Deterministic and Probabilistic Approaches for Assessing the Aquatic Ecological Risk of Pesticides in a Mixed Land Use Basin: A Case Study in Uruguay. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 910, 168704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.-H.; Wu, F.-C.; He, H.-P.; Zhang, R.-Q.; Li, H.-X. Screening Level Ecological Risk Assessment for Synthetic Musks in Surface Water of Lake Taihu, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2013, 27, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.X.; Aris, A.; Yong, E.L.; Noor, Z.Z. Evaluation of the Occurrence of Antibiotics at Different Treatment Stages of Decentralised and Conventional Sewage Treatment Plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 5547–5562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, S.; Davoli, E.; Riva, F.; Palmiotto, M.; Camporini, P.; Manenti, A.; Zuccato, E. Mass Balance of Emerging Contaminants in the Water Cycle of a Highly Urbanized and Industrialized Area of Italy. Water Res. 2018, 131, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglioni, S.; Zuccato, E.; Fattore, E.; Riva, F.; Terzaghi, E.; Koenig, R.; Principi, P.; Di Guardo, A. Micropollutants in Lake Como Water in the Context of Circular Economy: A Snapshot of Water Cycle Contamination in a Changing Pollution Scenario. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, J.L.; Berset, J.D.; Kannan, K. Mass Flow of Polycyclic Musks in Two Wastewater Treatment Plants. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2007, 52, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Li, F.; Xiao, X.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; You, J. Ecological Risk of Galaxolide and Its Transformation Product Galaxolidone: Evidence from the Literature and a Case Study in Guangzhou Waterways. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2023, 25, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, K. Retention Characteristics and Balance Assessment for Two Polycyclic Musk Fragrances (HHCB and AHTN) in a Typical German Sewage Treatment Plant. Chemosphere 2004, 57, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, S.; Di Carro, M.; Ianni, C.; Magi, E. Occurrence of PCPs in Natural Waters from Europe. In Personal Care Products in the Aquatic Environment; Díaz-Cruz, M.S., Barceló, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 37–71. ISBN 978-3-319-18809-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, C.; Sara, V.; Luca, R.; Andrea, M.; Valeria, L. Levels and Ecological Risk of Selected Organic Pollutants in the High-Altitude Alpine Cryosphere—The Adamello-Brenta Natural Park (Italy) as a Case Study. Environ. Adv. 2022, 7, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneta, B.G.; Feo, M.L.; Torre, M.; Tratzi, P.; Aita, S.E.; Montone, C.M.; Taglioni, E.; Mosca, S.; Balducci, C.; Cerasa, M.; et al. Occurrence of Per- and Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances in Wastewater Treatment Plants in Northern Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 165089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglioni, S.; Valsecchi, S.; Polesello, S.; Rusconi, M.; Melis, M.; Palmiotto, M.; Manenti, A.; Davoli, E.; Zuccato, E. Sources and Fate of Perfluorinated Compounds in the Aqueous Environment and in Drinking Water of a Highly Urbanized and Industrialized Area in Italy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 282, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, M.K.; Miyake, Y.; Yeung, W.Y.; Ho, Y.M.; Taniyasu, S.; Rostkowski, P.; Yamashita, N.; Zhou, B.S.; Shi, X.J.; Wang, J.X.; et al. Perfluorinated Compounds in the Pearl River and Yangtze River of China. Chemosphere 2007, 68, 2085–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Xia, X.; Dong, J.; Xia, N.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y. Short- and Long-Chain Perfluoroalkyl Substances in the Water, Suspended Particulate Matter, and Surface Sediment of a Turbid River. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 568, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Robinson, J.; Chong, M.F. A Review on Application of Flocculants in Wastewater Treatment. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2014, 92, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvelas, M.; Katsoyiannis, A.; Samara, C. Occurrence and Fate of Heavy Metals in the Wastewater Treatment Process. Chemosphere 2003, 53, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marziali, L.; Valsecchi, L.; Schiavon, A.; Mastroianni, D.; Viganò, L. Vertical Profiles of Trace Elements in a Sediment Core from the Lambro River (Northern Italy): Historical Trends and Pollutant Transport to the Adriatic Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, F.Y.; Ong, S.L.; Hu, J. Recent Advances in the Use of Chemical Markers for Tracing Wastewater Contamination in Aquatic Environment: A Review. Water 2017, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstea, E.M.; Bridgeman, J.; Baker, A.; Reynolds, D.M. Fluorescence Spectroscopy for Wastewater Monitoring: A Review. Water Res. 2016, 95, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, A.; Pontvianne, S.; Pons, M.-N. Photodegradation-Based Detection of Fluorescent Whitening Agents in a Mountain River. Chemosphere 2014, 100, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Yoom, H.; Son, H.; Seo, C.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.M. Removal Efficiency of Organic Micropollutants in Successive Wastewater Treatment Steps in a Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plant: Bench-Scale Application of Tertiary Treatment Processes to Improve Removal of Organic Micropollutants Persisting after Secondary Treatment. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, D.-J.; Kim, C.-S.; Park, J.-W.; Lee, S.-H.; Chung, H.-M.; Jeong, D.-H. Spatial Variation of Pharmaceuticals in the Unit Processes of Full-Scale Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 286, 112150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behera, S.K.; Kim, H.W.; Oh, J.-E.; Park, H.-S. Occurrence and Removal of Antibiotics, Hormones and Several Other Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Treatment Plants of the Largest Industrial City of Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 4351–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieno, N.; Sillanpää, M. Fate of Diclofenac in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant—A Review. Environ. Int. 2014, 69, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, S.; Wu, P.; Tsang, Y.F. Occurrence and Fate of Antibiotics in a Wastewater Treatment Plant and Their Biological Effects on Receiving Waters in Guizhou. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 113, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, X.; Li, W.; Wei, Z.; Spinney, R.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Seo, Y.; Tang, C.-J.; Li, Q.; Xiao, R. Sorption and Biodegradation of Pharmaceuticals in Aerobic Activated Sludge System: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical Mechanistic Study. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 342, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorival-García, N.; Zafra-Gómez, A.; Navalón, A.; González-López, J.; Hontoria, E.; Vílchez, J.L. Removal and Degradation Characteristics of Quinolone Antibiotics in Laboratory-Scale Activated Sludge Reactors under Aerobic, Nitrifying and Anoxic Conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 120, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Zhang, T. Biodegradation and Adsorption of Antibiotics in the Activated Sludge Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3468–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Chen, H.; Reinhard, M.; Mao, F.; Gin, K.Y.-H. Occurrence and Removal of Multiple Classes of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Agents in Biological Wastewater Treatment Processes. Water Res. 2016, 104, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chu, L.; Wojnárovits, L.; Takács, E. Occurrence and Fate of Antibiotics, Antibiotic Resistant Genes (ARGs) and Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria (ARB) in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant: An Overview. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744, 140997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Wu, C.; Xiao, K.; Huang, X.; Zhou, H.; Tsuno, H.; Tanaka, H. Elimination and Fate of Selected Micro-Organic Pollutants in a Full-Scale Anaerobic/Anoxic/Aerobic Process Combined with Membrane Bioreactor for Municipal Wastewater Reclamation. Water Res. 2010, 44, 5999–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, S.; Lema, J.M.; Omil, F. Removal of Pharmaceutical and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) under Nitrifying and Denitrifying Conditions. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3214–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, A.; Thomsen, A.; McArdell, C.S.; Joss, A.; Giger, W. Occurrence and Sorption Behavior of Sulfonamides, Macrolides, and Trimethoprim in Activated Sludge Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 3981–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, A.J.; Brown, A.K.; Wong, C.S.; Yuan, Q. Removal of Antibiotic Sulfamethoxazole by Anoxic/Anaerobic/Oxic Granular and Suspended Activated Sludge Processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 251, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Sui, Q.; Mei, X.; Cheng, X. Efficient Elimination of Sulfonamides by an Anaerobic/Anoxic/Oxic-Membrane Bioreactor Process: Performance and Influence of Redox Condition. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, P.H.; Thomas, K.V. The Occurrence of Selected Pharmaceuticals in Wastewater Effluent and Surface Waters of the Lower Tyne Catchment. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 356, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batt, A.L.; Bruce, I.B.; Aga, D.S. Evaluating the Vulnerability of Surface Waters to Antibiotic Contamination from Varying Wastewater Treatment Plant Discharges. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 142, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodayan, A.; Majewsky, M.; Yargeau, V. Impact of Approach Used to Determine Removal Levels of Drugs of Abuse during Wastewater Treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 487, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, R.; Marques, R.; Noronha, J.P.; Carvalho, G.; Oehmen, A.; Reis, M.A.M. Assessing the Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in a Full-Scale Activated Sludge Plant. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2012, 19, 1818–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Guardo, A.; Castiglioni, S.; Gambino, I.; Sailis, A.; Salmoiraghi, G.; Schiarea, S.; Vighi, M.; Terzaghi, E. Modelling Micropollutant Cycle in Lake Como in a Winter Scenario: Implications for Water Use and Reuse, Ecosystem Services, and the EU Zero Pollution Action Plan. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. Occurrence of Pharmaceutical Compounds in Urban Wastewater: Removal, Mass Load and Environmental Risk after a Secondary Treatment—A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evgenidou, E.N.; Konstantinou, I.K.; Lambropoulou, D.A. Occurrence and Removal of Transformation Products of PPCPs and Illicit Drugs in Wastewaters: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 505, 905–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Duan, J.; Tian, S.; Ji, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, D. Short-Chain per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Aquatic Systems: Occurrence, Impacts and Treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yan, H.; Li, F.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Q. Sorption of Short- and Long-Chain Perfluoroalkyl Surfactants on Sewage Sludges. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 260, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, S.P.; Kah, M.; Padhye, L.P. A Review of the Occurrence, Transformation, and Removal of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Wastewater Treatment Plants. Water Res. 2021, 199, 117187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Nishimura, F.; Hidaka, T. Effects of Microbial Activity on Perfluorinated Carboxylic Acids (PFCAs) Generation during Aerobic Biotransformation of Fluorotelomer Alcohols in Activated Sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 776–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, J.; Buck, R.C.; Korzeniowski, S.H.; Wolstenholme, B.W.; Folsom, P.W.; Sulecki, L.M. 6:2 Fluorotelomer Sulfonate Aerobic Biotransformation in Activated Sludge of Waste Water Treatment Plants. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaili, H.; Ng, C. Adsorption as a Remediation Technology for Short-Chain per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Water—A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2023, 9, 344–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Casteel, K.; Dai, H.; Wehmeyer, K.R.; Kiel, B.; Federle, T. Distributions of Polycyclic Musk Fragrance in Wastewater Treatment Plant (WWTP) Effluents and Sludges in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košnář, Z.; Mercl, F.; Chane, A.D.; Pierdonà, L.; Míchal, P.; Tlustoš, P. Occurrence of Synthetic Polycyclic and Nitro Musk Compounds in Sewage Sludge from Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biel-Maeso, M.; Corada-Fernández, C.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Removal of Personal Care Products (PCPs) in Wastewater and Sludge Treatment and Their Occurrence in Receiving Soils. Water Res. 2019, 150, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Guardia, M.; Hale, R.; Harvey, E.; Bush, E.; Mainor, T.; Gaylor, M. Emerging Chemicals of Concern in Biosolids. Proc. Water Environ. Fed. 2003, 19, 1134–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | River Upstream | WWTP Inflow | WWTP Outflow | River Downstream |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfluorinated compounds (ng L−1) | ||||

| GenX | 2.5–22 10 ± 8 | 59–79 69 ± 8 | 2.5–72 35 ± 31 | 2.5–52 21 ± 19 |

| PFHpA | 2.5–7 5 ± 2 | 2.5–2.5 2.5 ± 0 | 11–24 19 ± 5 | 5–12 7 ± 3 |

| PFHxA | 9–15 12 ± 2 | 2.5–12 7 ± 3 | 26–58 45 ± 12 | 11–27 16 ± 6 |

| PFPeA | 11–18 14 ± 3 | 2.5–120 36 ± 51 | 38–95 70 ± 23 | 9–57 23 ± 19 |

| PFOA | 6–9 7 ± 1 | 2.5–6 4 ± 2 | 7–11 9 ± 1 | 5–7 6 ± 1 |

| Pharmaceuticals (ng L−1) | ||||

| Amox | 25–59 36 ± 14 | 25–100 70 ± 28 | 64–120 91 ± 23 | 25–63 40 ± 17 |

| Aten | 26–71 47 ± 17 | 380–690 584 ± 124 | 120–130 126 ± 5 | 25–190 62 ± 72 |

| Azit | 160–640 294 ± 204 | 810–1400 1162 ± 226 | 1400–1900 1560 ± 207 | 170–1300 416 ± 495 |

| Carb | 64–180 97 ± 47 | 180–330 260 ± 54 | 350–440 396 ± 39 | 64–280 120 ± 90 |

| Cipr | 10–180 81 ± 81 | 650–2400 1610 ± 721 | 450–650 548 ± 84 | 30–520 137 ± 214 |

| Clar | 90–280 140 ± 79 | 520–850 706 ± 146 | 560–600 576 ± 15 | 100–430 178 ± 142 |

| Dicl | 180–610 320 ± 167 | 550–1700 1270 ± 463 | 1400–2700 2160 ± 532 | 170–1400 486 ± 514 |

| Eryt | 210–580 348 ± 138 | 650–1800 1164 ± 427 | 950–1800 1350 ± 350 | 180–9700 2156 ± 4218 |

| Gemf | 10–27 13 ± 8 | 25–170 101 ± 52 | 65–90 74 ± 10 | 10–57 19 ± 21 |

| Napr | 10–170 79 ± 62 | 960–2000 1512 ± 433 | 150–220 188 ± 31 | 43–360 117 ± 136 |

| Prim | 23–75 42 ± 20 | 78–190 140 ± 42 | 150–230 192 ± 32 | 28–130 56 ± 42 |

| Sulf | 60–140 90 ± 31 | 220–510 412 ± 113 | 230–270 246 ± 17 | 55–220 10 ± 65 |

| Trim | 25–67 37 ± 18 | 58–140 107 ± 31 | 130–170 154 ± 17 | 22–120 46 ± 42 |

| Fragrances (ng L−1) | ||||

| ADBI | 0.5–3.0 1.3 ± 1.1 | 2.0–7.0 4.4 ± 1.8 | 6.0–8.0 6.8 ± 0.8 | 1.0–4.0 1.6 ± 1.3 |

| AHTN | 36–112 62 ± 36 | 76–295 179 ± 87 | 227–266 246 ± 16 | 38–196 71 ± 70 |

| HHCB | 635.0–2088.0 1088.0 ± 635.9 | 1541.0–4857.0 3092.0 ± 1293.7 | 5100.0–5795.0 5456.6 ± 288.8 | 684.0–3230.0 1236.6 ± 1115.0 |

| HHCB-L | 144.0–411.0 212.8 ± 111.6 | 239.0–454.0 366.4 ± 87.9 | 912.0–1094.0 984.2 ± 69.3 | 161.0–677.0 277.8 ± 223.4 |

| Trace elements in whole water samples (µg L−1) | ||||

| Al | 108–406 241 ± 130 | 19–462 341 ± 112 | 164–2964 79 ± 1214 | 132–219 170 ± 33 |

| As | 1.1–1.2 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.5–1.1 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.5–0.7 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.0–1.3 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Ba | 19.9–24.2 22.5 ± 1.6 | 26.0–38.6 32.9 ± 4.6 | 16.0–19.0 17.4 ± 1.2 | 17.3–23.1 21.4 ± 2.4 |

| Co | 5–10 6 ± 2 | 3–10 7 ± 3 | 0.5–9 4 ± 3 | 0.5–0.5 0.5 ± 0.0 |

| Cr | 2.6–3.6 3.0 ± 0.5 | 10.2–24.0 16.2 ± 5.9 | 7.6–12.0 9.6 ± 2.1 | 2.6–11.9 4.6 ± 4.1 |

| Fe | 88–175 121 ± 38 | 101–432 249 ± 147 | 128–2262 594 ± 933 | 19–114 63 ± 35 |

| Mn | 10–19 12 ± 4 | 6–25 13 ± 8 | 9–23 15 ± 5.4 | 5–13 10 ± 3 |

| Ni | 1.2–5.0 2.1 ± 1.6 | 6.1–112.0 27.8 ± 47.1 | 8.1–17.4 12. ± 3.40 | 1.2–18.6 4.9 ± 7.6 |

| Pb | 0.5–0.5 0.5 ± 0.0 | 1.5–2.5 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.0–2.5 1.6 ± 0.5 | 0.5–0.5 0.5 ± 0.0 |

| Sb | 0.5–5 2 ± 2 | 2–23 12 ± 8 | 0.5–10 6 ± 4 | 0–5 3 ± 2 |

| Se | 3–26 14 ± 8 | 4–30 20 ± 11 | 6–19 12 ± 5 | 4–17 9 ± 5 |

| V | 16–52 36 ± 15 | 8–50 35 ± 16 | 12–57 39 ± 17 | 11–48 33 ± 16 |

| Zn | 13–30 20 ± 7 | 17–103 58 ± 37 | 3–28 12 ± 11 | 12–30 23 ± 8 |

| Dissolved trace elements (µg L−1) | ||||

| Al | 57–142 84 ± 34 | 76–131 101 ± 24 | 66–186 99 ± 51 | 38–103 67 ± 25 |

| Co | 0.5–5 3 ± 2 | 0.5–9 3 ± 3 | 0.5–3 1 ± 1 | 0.5–0.5 0.5 ± 0.0 |

| Fe | 31–146 92 ± 41 | 7.5–102 65 ± 41 | 7.5–208 74 ± 91 | 7.5–75 31 ± 35 |

| Mn | 6–18 11 ± 4 | 6–25 12 ± 8 | 8–15 13 ± 3 | 2–13 6 ± 5 |

| Ni | 0.5–10 3 ± 4 | 5–87 24 ± 36 | 0.5–9 3 ± 3 | 0.5–14 3 ± 6 |

| Se | 2–11 5 ± 4 | 1–10 6 ± 3 | 0.5–4 2 ± 2 | 0.5–7 4 ± 3 |

| Sb | 0.5–5 1 ± 2 | 0.5–17 7 ± 6 | 0.5–5 1 ± 2 | 0.5–2 1 ± 1 |

| V | 9–42 21 ± 13 | 8–47 25 ± 18 | 8–43 23 ± 14 | 4–19 13 ± 6 |

| Zn | 13–22 17 ± 4 | 3–22 13 ± 8 | 3–25 11 ± 10 | 10–20 15 ± 4 |

| Nutrients (mg L−1) | ||||

| TN | 2–7 4 ± 2 | 23–61 50 ± 15 | 13–25 18 ± 5 | 0.5–14 4 ± 6 |

| TP | 0.18–0.53 0.33 ± 0.16 | 2.80–3.80 3.32 ± 0.38 | 0.74–1.20 0.93 ± 0.19 | 0.15–1.20 0.43 ± 0.44 |

| TOC | 3–19 8 ± 7 | 49–97 70 ± 18 | 7–33 14 ± 11 | 0.5–19 9 ± 8 |

| Microbiological parameters (MPN 100 mL−1) | ||||

| Thermotolerant coliform (F_Col) | 2200–7.9 × 105 163,720 ± 350,123 | 1600–3.5 × 108 12,420,320 ± 13,521,541 | 330–7000 2306 ± 2723 | 2200–2.3 × 106 464,100 ± 1,026,302 |

| E. coli * (E_Col) | 400–5 × 105 101,520 ± 222,761 | 1 × 106–9.8 × 106 3,760,000 ± 3,604,580 | 120–1000 498 ± 323 | 290–1.1 × 106 221,356 ± 491,178 |

| Thermotolerant coliform (T_Col) | 5400–1.7 × 106 361,080 ± 748,732 | 3.5 × 107–9.2 × 107 6.54 × 107 ± 25,491,175 | 7000–9.2 × 107 18,422,800 ± 41,130,916 | 3300–1.1 × 107 2,216,100 ± 4,910,369 |

| Tracers (µg L−1) | ||||

| Caff | 0.1–3 0.7 ± 1.2 | 28–50 43.8 ± 9.1 | 0.05–0.2 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1–8.9 1.9 ± 3.9 |

| Total B (T_B) | 25–52 39 ± 8 | 160–300 234 ± 61 | 140–310 252 ± 70 | 25–81 45 ± 20 |

| Total Cl (T_Cl) | 23–56 33 ± 13 | 120–140 130 ± 10 | 110–130 122 ± 8 | 25–92 42 ± 28 |

| MBAS | 50–150 70 ± 45 | 170–3300 1014 ± 1290 | 50–220 140 ± 64 | 50–160 72 ± 49 |

| Loads (g Day−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Compound | Influent (IN) | Effluent (OUT) | RE% | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| PFOA | 0.66 | 0.30 | 1.17 | 0.19 | −78 ± 107 |

| PFHpA | 0.36 | 0.04 | 2.48 | 0.78 | −589 ± 286 |

| PFHxA | 1.02 | 0.49 | 5.97 | 1.99 | −487 ± 425 |

| PFPeA | 5.71 | 8.62 | 9.06 | 3.06 | −59 ± 305 |

| GenX | 10.05 | 2.22 | 4.52 | 4.04 | 55 ± 51 |

| Amox | 10.16 | 4.20 | 11.76 | 3.26 | −16 ± 72 |

| Aten | 84.74 | 23.51 | 16.34 | 1.45 | 81 ± 7 |

| Azit | 167.94 | 40.36 | 204.66 | 47.50 | −22 ± 50 |

| Carb | 37.91 | 11.51 | 51.50 | 7.79 | −36 ± 57 |

| Cipr | 232.69 | 104.95 | 71.20 | 13.31 | 69 ± 18 |

| Clar | 102.37 | 27.92 | 74.97 | 9.30 | 27 ± 27 |

| Dicl | 185.41 | 78.70 | 280.07 | 68.65 | −51 ± 91 |

| Eryt | 171.45 | 81.24 | 178.27 | 62.06 | −4 ± 76 |

| Gemf | 10.64 | 1.44 | 2.67 | 3.14 | 75 ± 37 |

| Napr | 220.08 | 78.51 | 24.61 | 5.72 | 89 ± 6 |

| Prim | 20.27 | 7.28 | 24.97 | 4.89 | −23 ± 62 |

| Sulf | 59.34 | 16.86 | 32.07 | 4.81 | 46 ± 22 |

| Trim | 15.28 | 4.15 | 20.03 | 3.10 | −31 ± 51 |

| ADBI | 0.63 | 0.23 | 0.88 | 0.11 | −40 ± 68 |

| HHCB | 438.16 | 160.62 | 708.59 | 78.07 | −62 ± 77 |

| AHTN | 25.25 | 10.96 | 31.92 | 3.69 | −26 ± 70 |

| HHCB-L | 52.36 | 11.09 | 127.26 | 7.48 | −143 ± 66 |

| Variable | Range LAB | Range RT | Regression Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TN (mg L−1) | 1.2–61.0 | 3.4–76.9 | Ln (RT) = 0.7785 Ln (LAB) + 0.5735 | 0.85 |

| TP (mg L−1) | 0.15–1.20 | 0.21–2.07 | Ln (RT) = 1.1363 Ln (LAB) − 0.5795 | 0.94 |

| Thermotolerant coliforms (cfu mL−1) | 3.3 × 103–9.2 × 107 | 3.32 × 103–1.5 × 108 | Ln (RT) = 1.0335 Ln (LAB) − 0.7461 | 0.96 |

| Escherichia coli (cfu mL−1) | 1.20 × 102–9.80 × 106 | 1.5 × 102–7.5 × 106 | Ln (RT) = 0.925 Ln (LAB) + 1.2666 | 0.96 |

| Cl (mg L−1) | 23–140 | 23.8–135.5 | Ln (RT) = 0.9234 Ln (LAB) + 0.3388 | 0.98 |

| B (mg L−1) | 32–81 | 39.0–92.0 | Ln (RT) = 0.7455 Ln (LAB) + 1.2964 | 0.48 |

| MBAS (mg L−1) | 0.1–3.3 | 0.1–3.2 | Ln (RT) = 1.4286 Ln (LAB) − 2.2066 | 0.52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tasselli, S.; Marziali, L.; Guzzella, L.; Valsecchi, L.; Palumbo, M.T.; Salerno, F.; Copetti, D. Impact of Wastewater Treatment Plant Discharge on Water Quality of a Heavily Urbanized River in Milan Metropolitan Area: Traditional and Emerging Contaminant Analysis. Water 2025, 17, 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223276

Tasselli S, Marziali L, Guzzella L, Valsecchi L, Palumbo MT, Salerno F, Copetti D. Impact of Wastewater Treatment Plant Discharge on Water Quality of a Heavily Urbanized River in Milan Metropolitan Area: Traditional and Emerging Contaminant Analysis. Water. 2025; 17(22):3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223276

Chicago/Turabian StyleTasselli, Stefano, Laura Marziali, Licia Guzzella, Lucia Valsecchi, Maria Teresa Palumbo, Franco Salerno, and Diego Copetti. 2025. "Impact of Wastewater Treatment Plant Discharge on Water Quality of a Heavily Urbanized River in Milan Metropolitan Area: Traditional and Emerging Contaminant Analysis" Water 17, no. 22: 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223276

APA StyleTasselli, S., Marziali, L., Guzzella, L., Valsecchi, L., Palumbo, M. T., Salerno, F., & Copetti, D. (2025). Impact of Wastewater Treatment Plant Discharge on Water Quality of a Heavily Urbanized River in Milan Metropolitan Area: Traditional and Emerging Contaminant Analysis. Water, 17(22), 3276. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223276