Stability Analysis of Loess Slope Under Heavy Rainfall Considering Joint Effect—Case Study of Jianxi Landslide, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting of Jianxi Landslide

2.1. Geographical Environment Feature

2.2. Hydrometeorological Characteristics

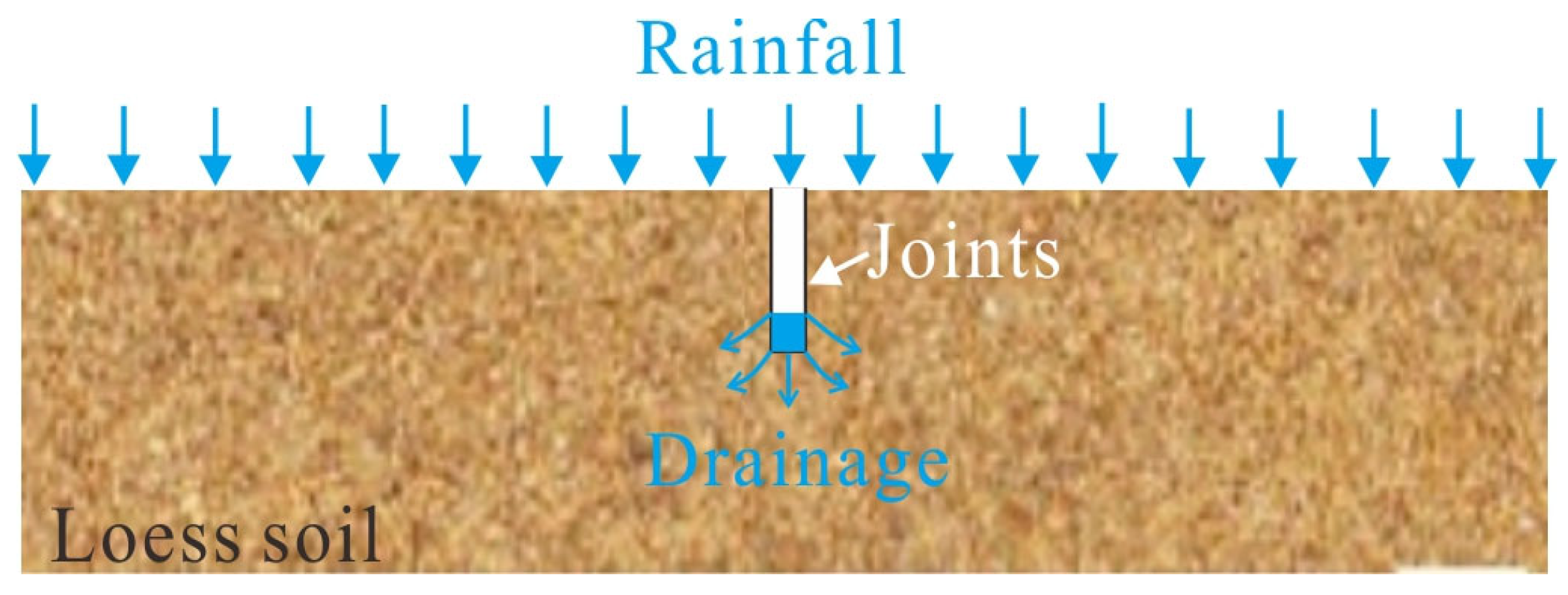

3. Numerical Model Establishment

3.1. Finite Element Model Establishment

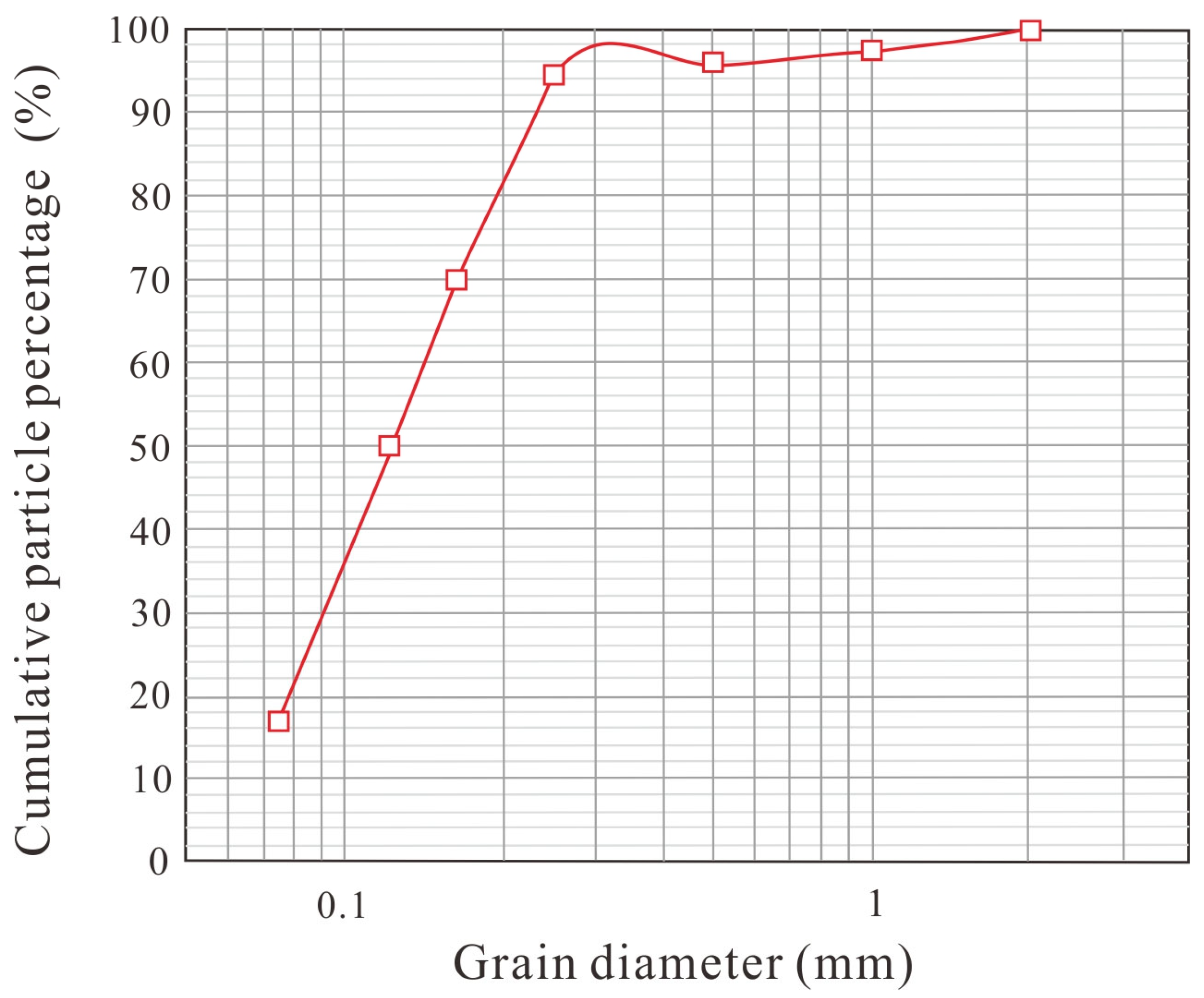

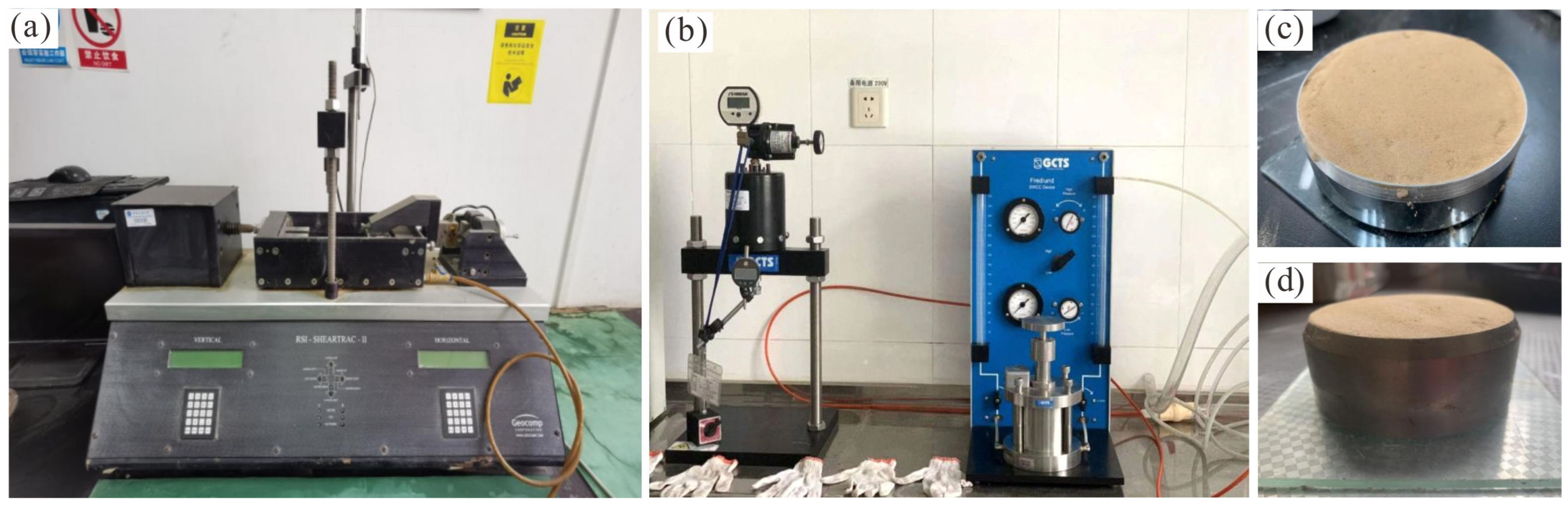

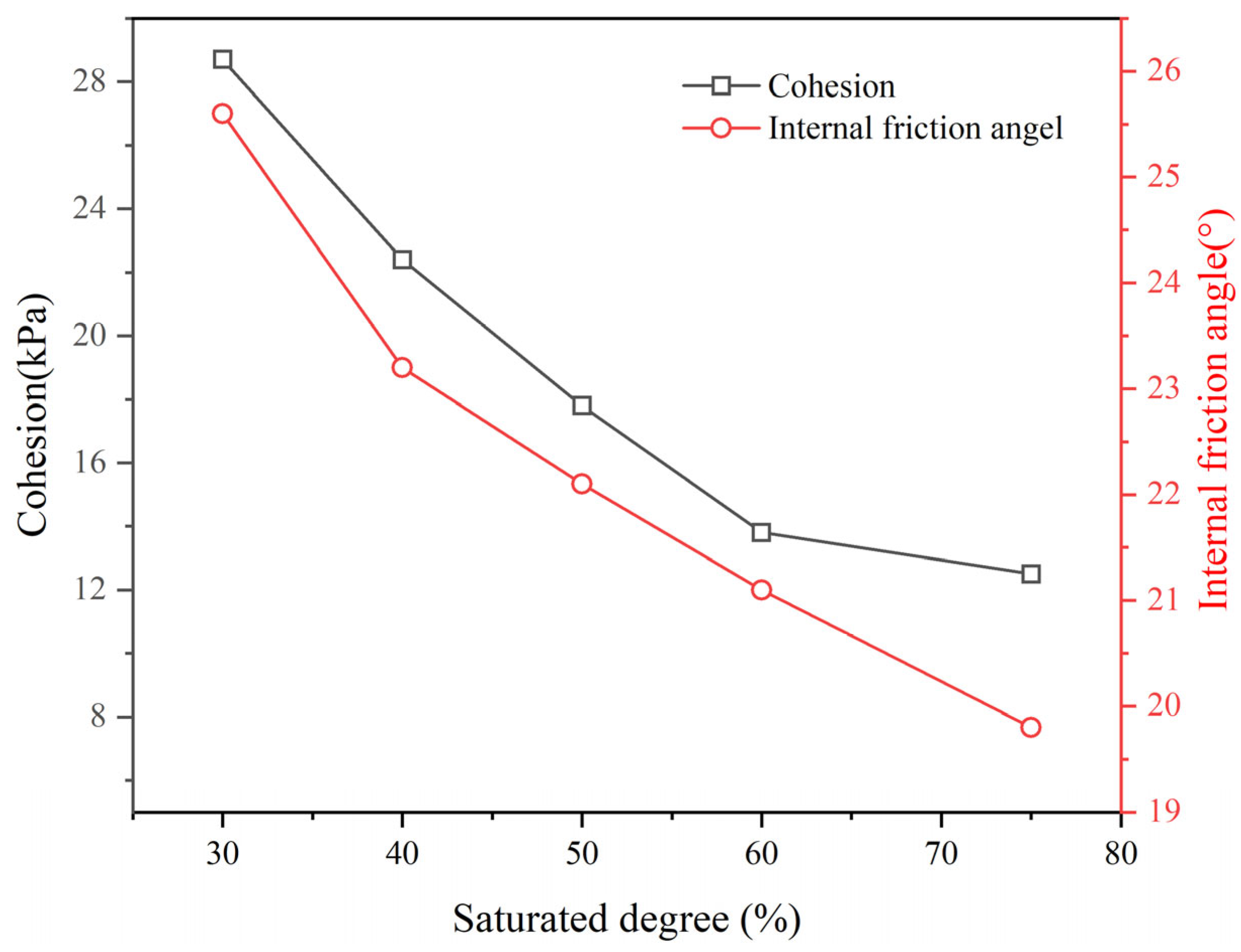

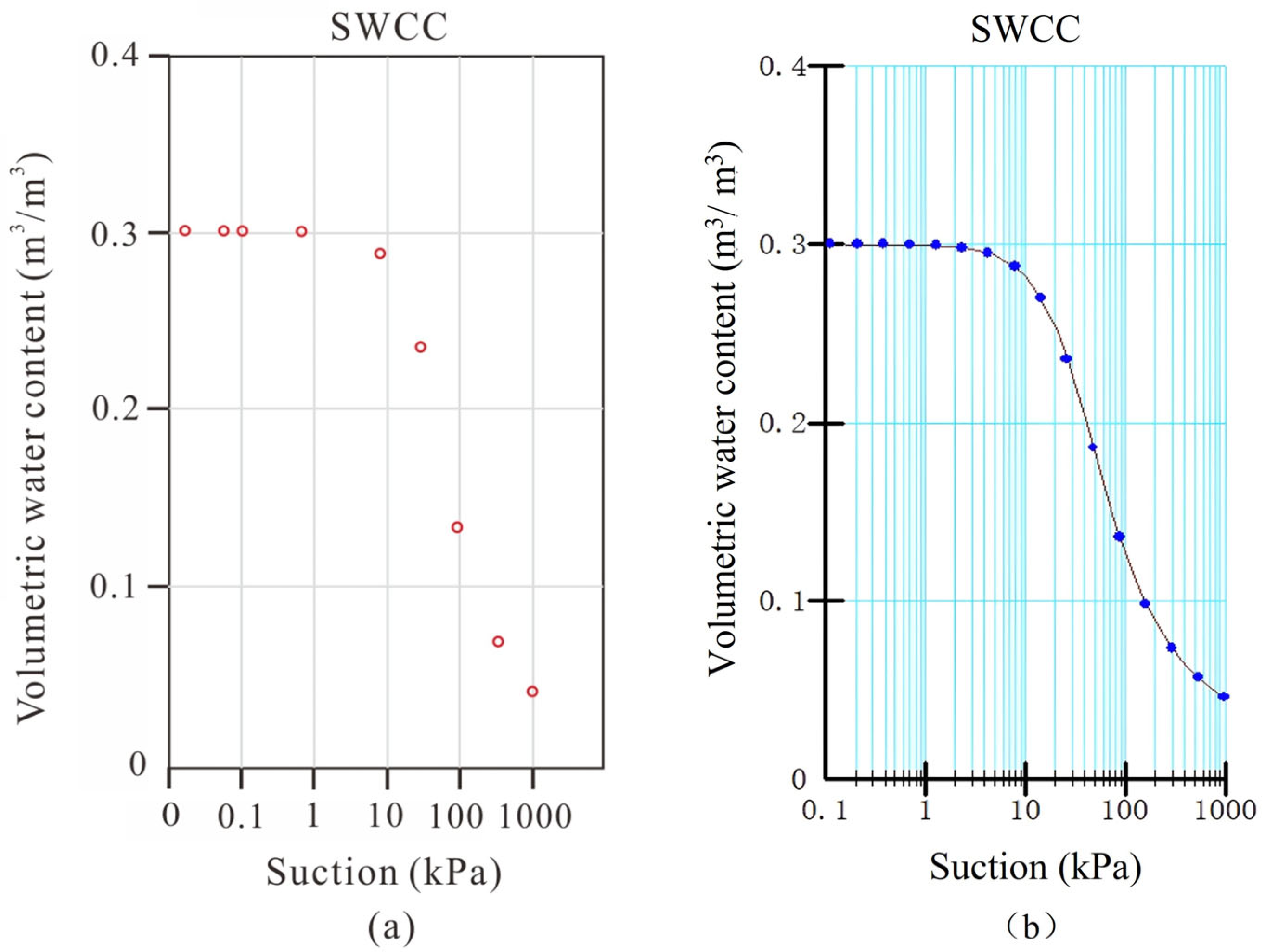

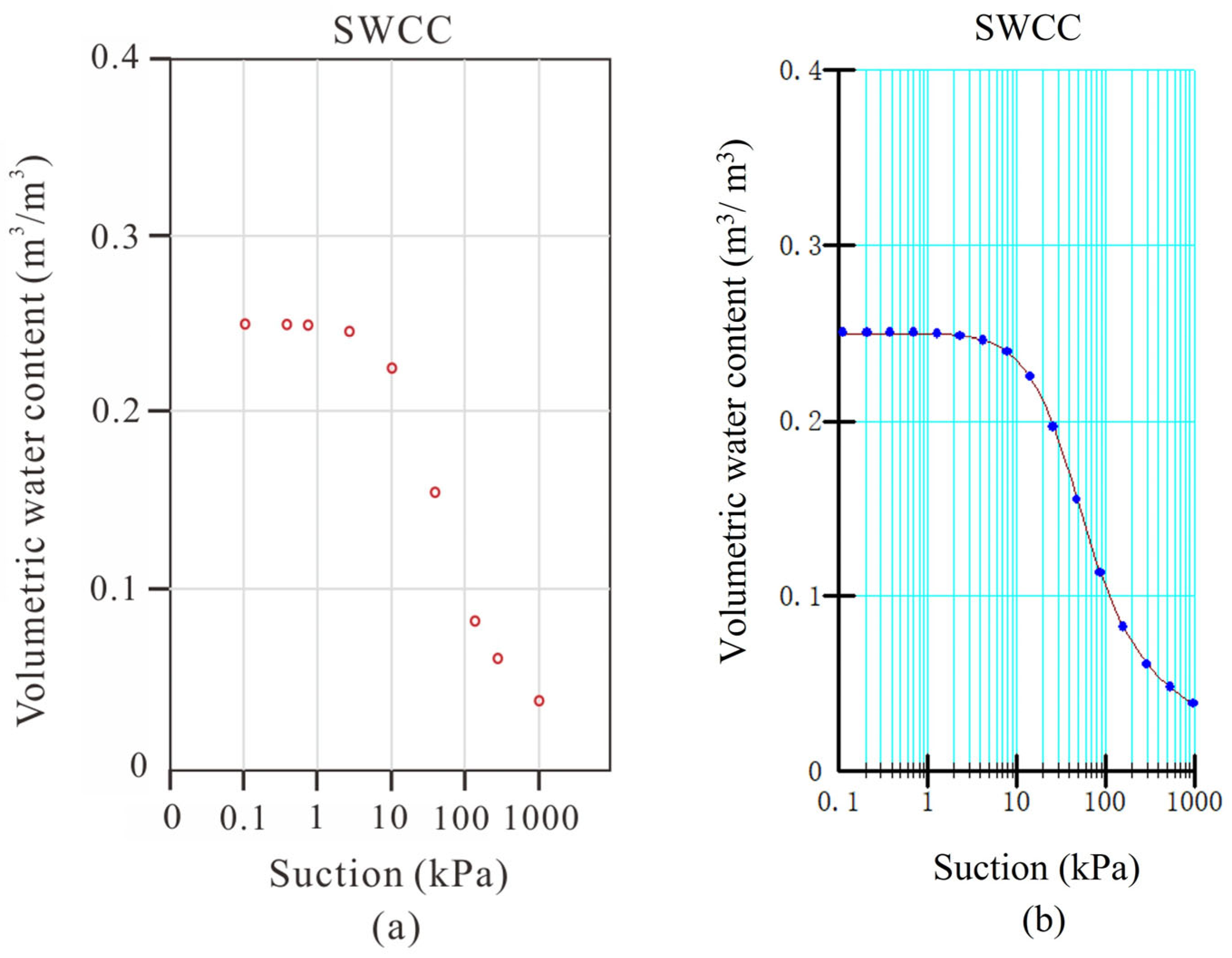

3.2. Soil Parameters

4. Results

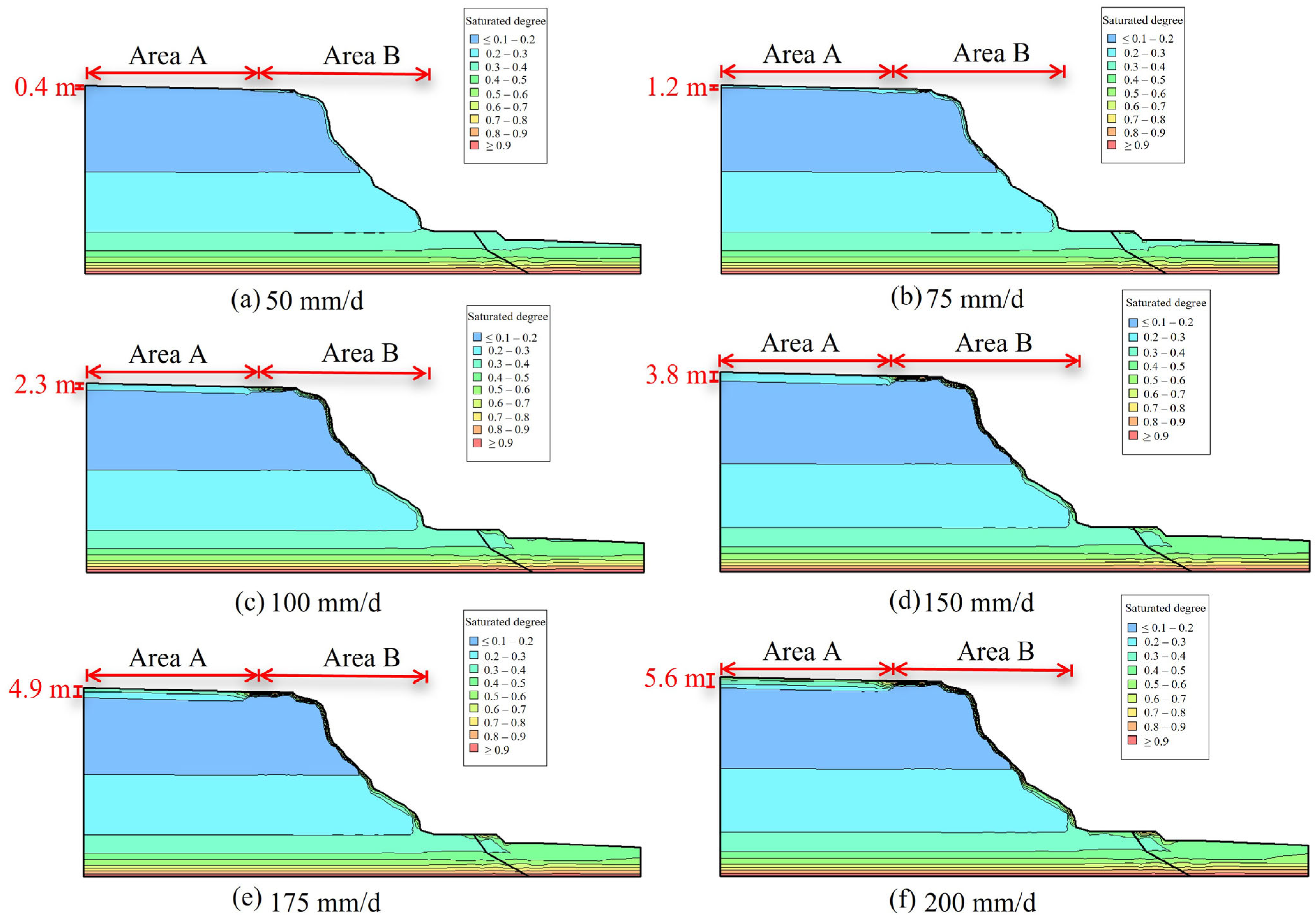

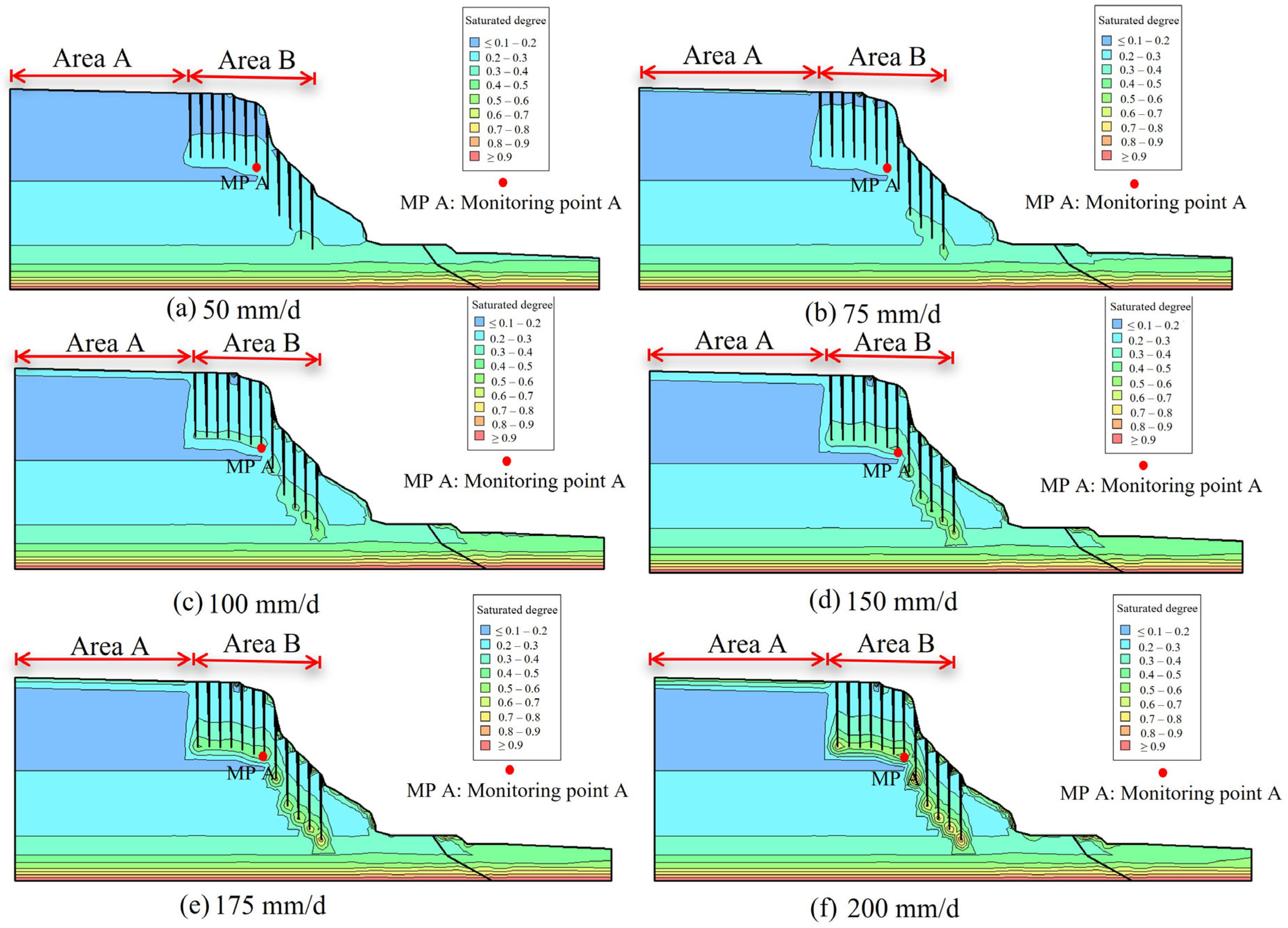

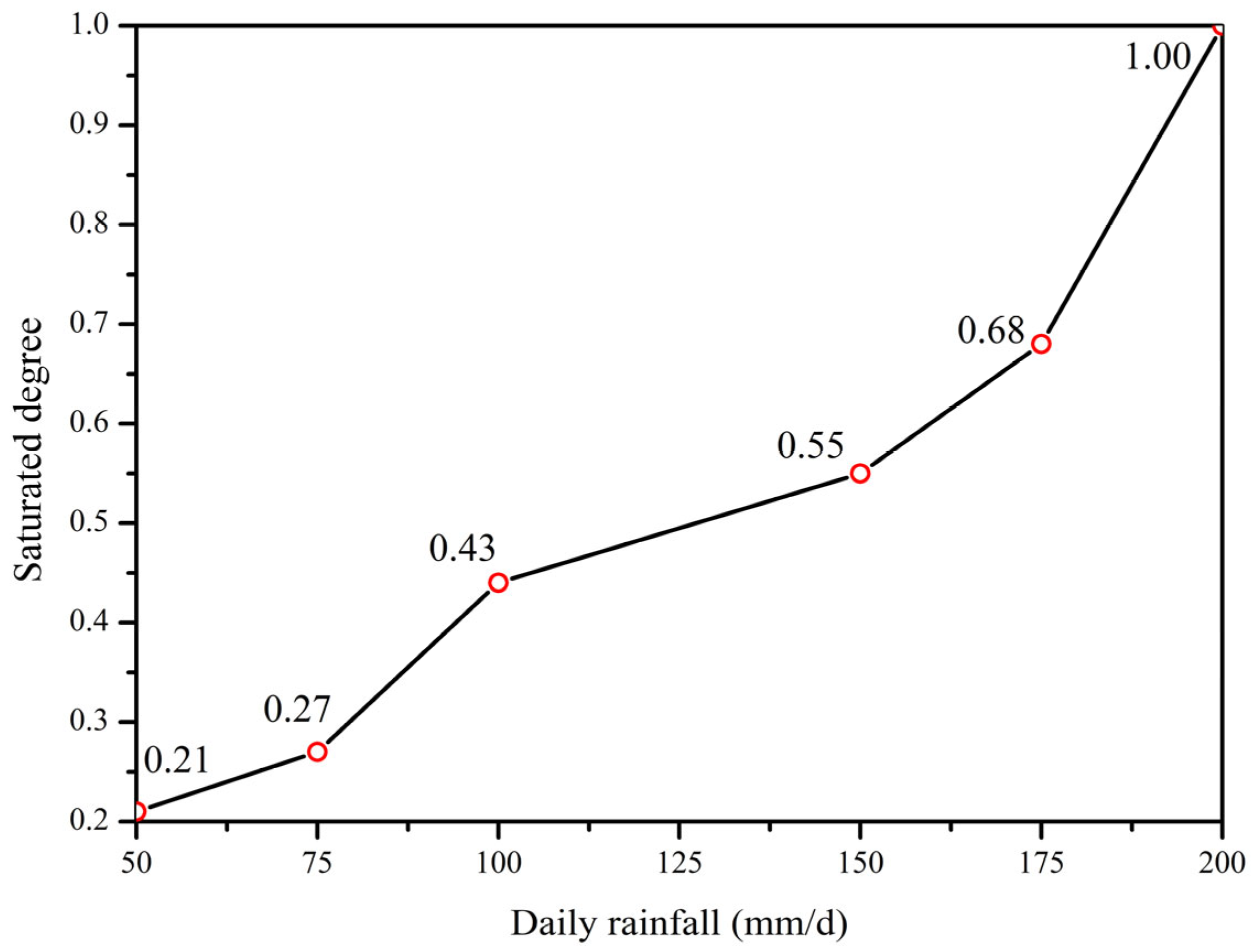

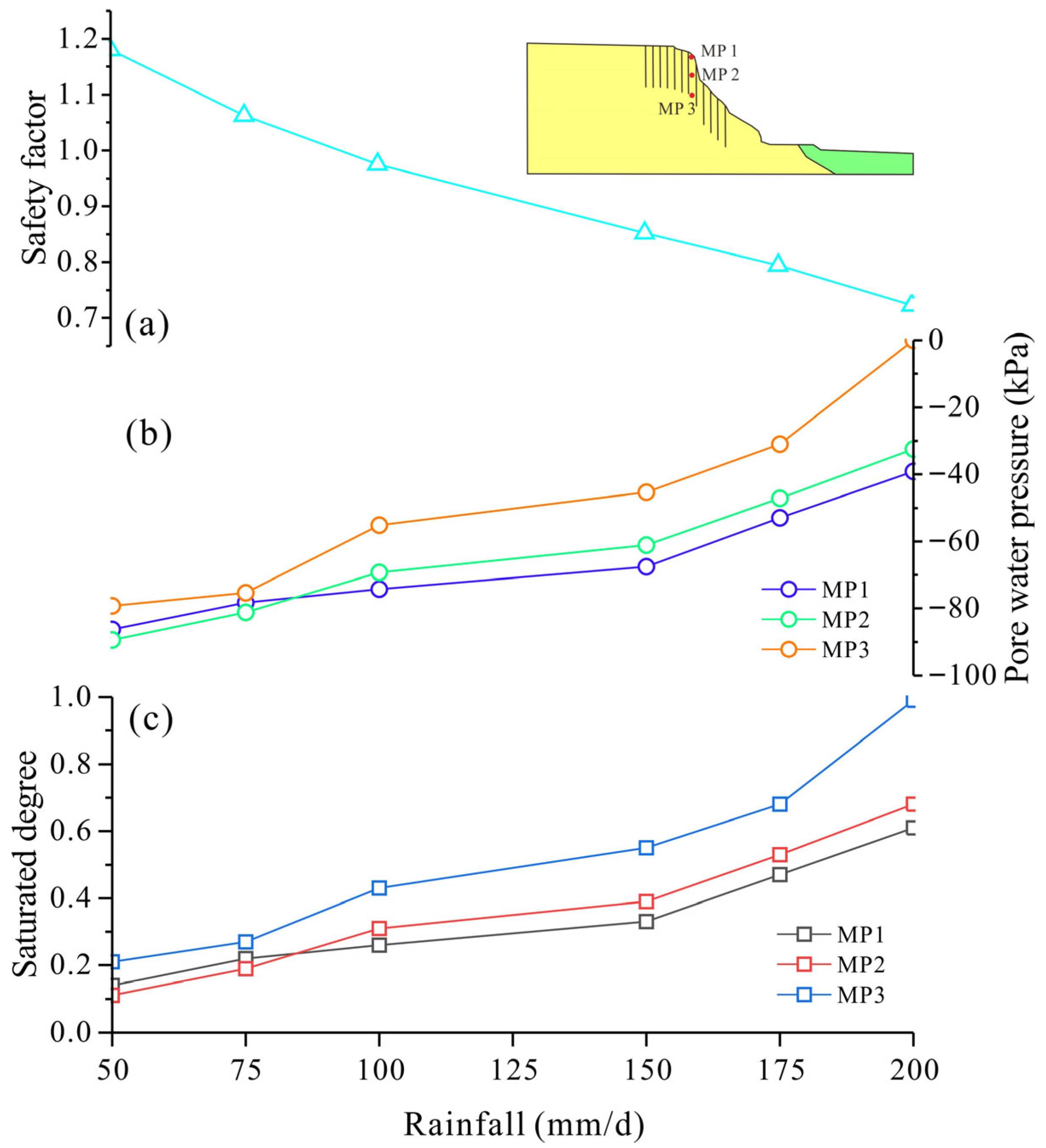

4.1. Soil Moisture Field

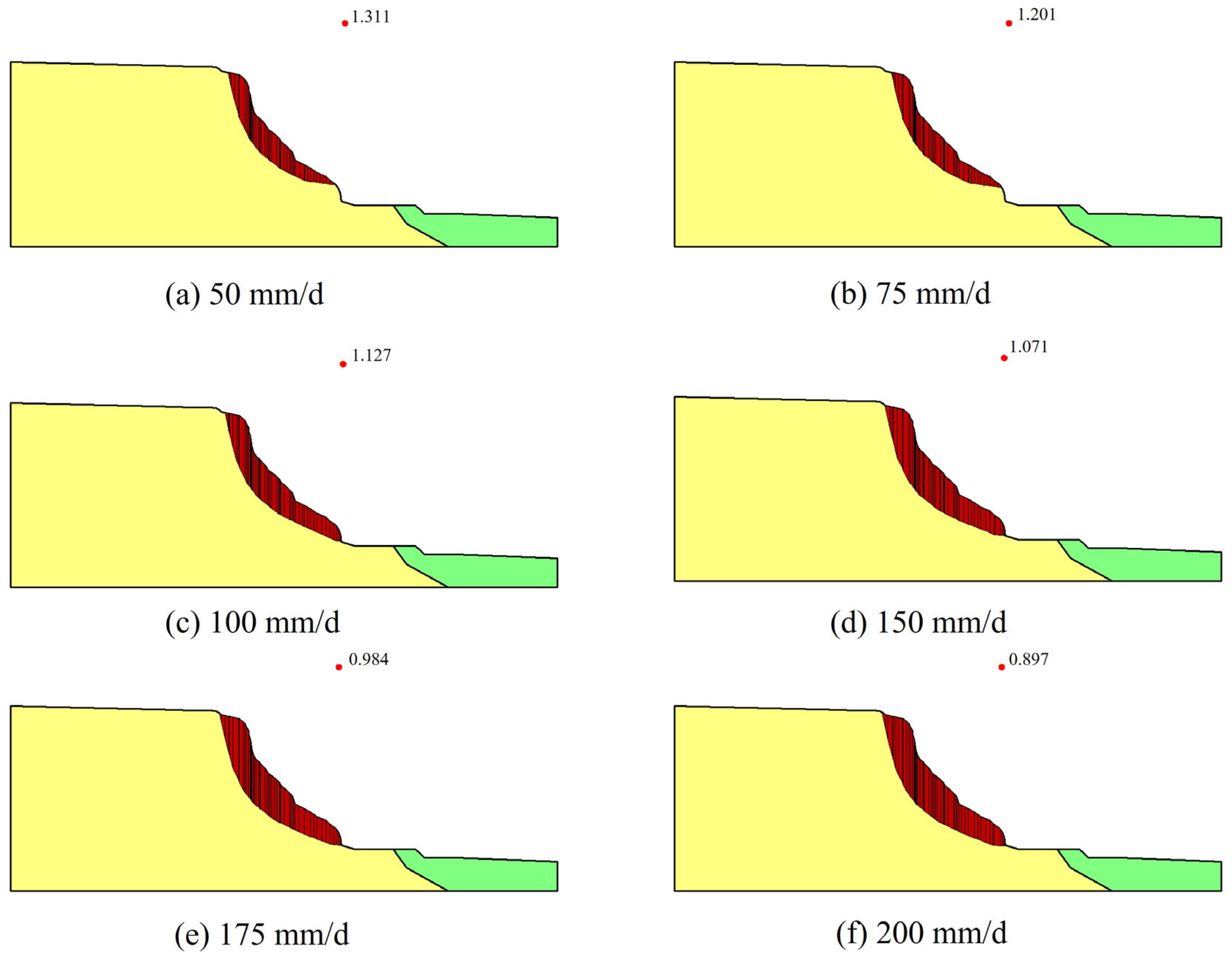

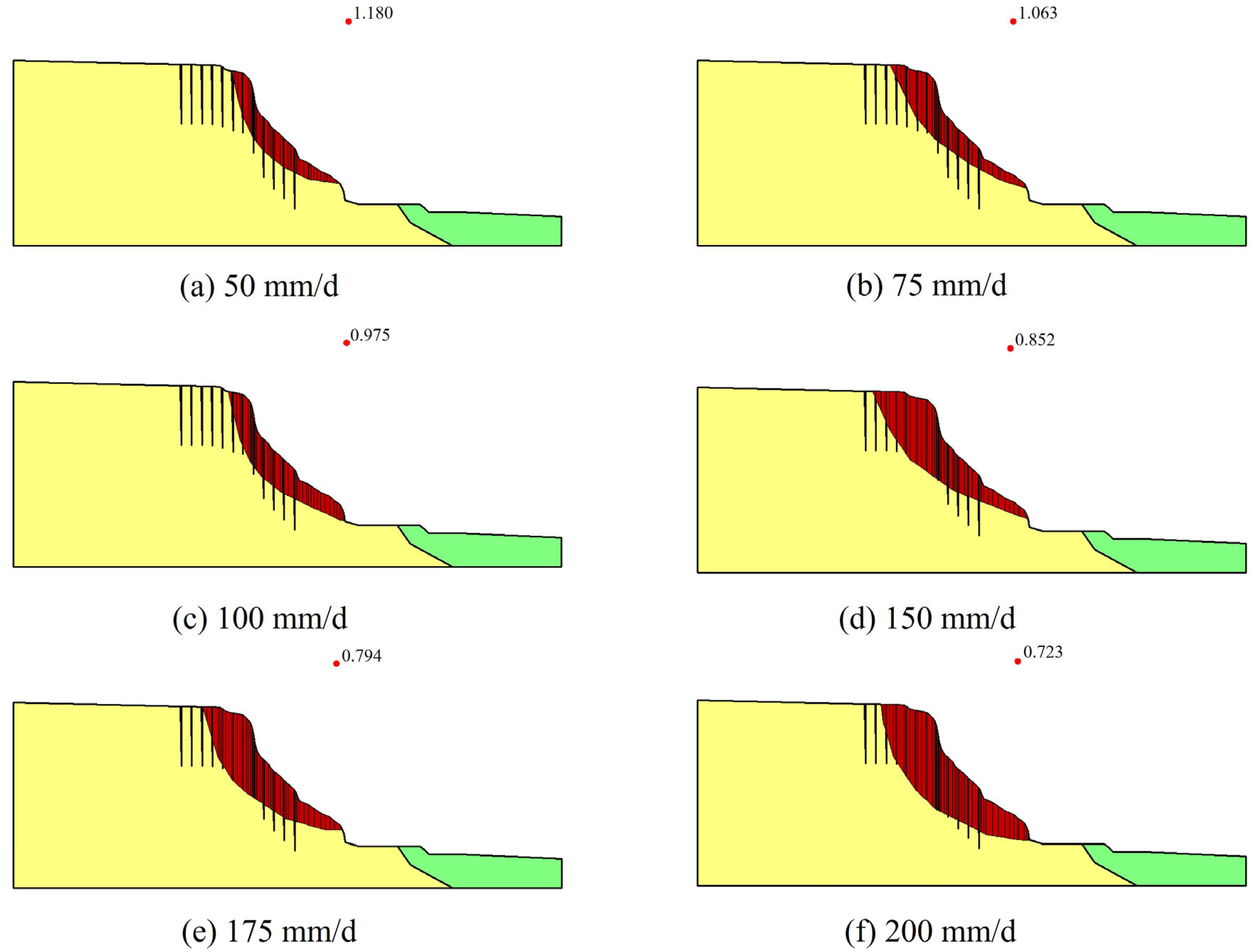

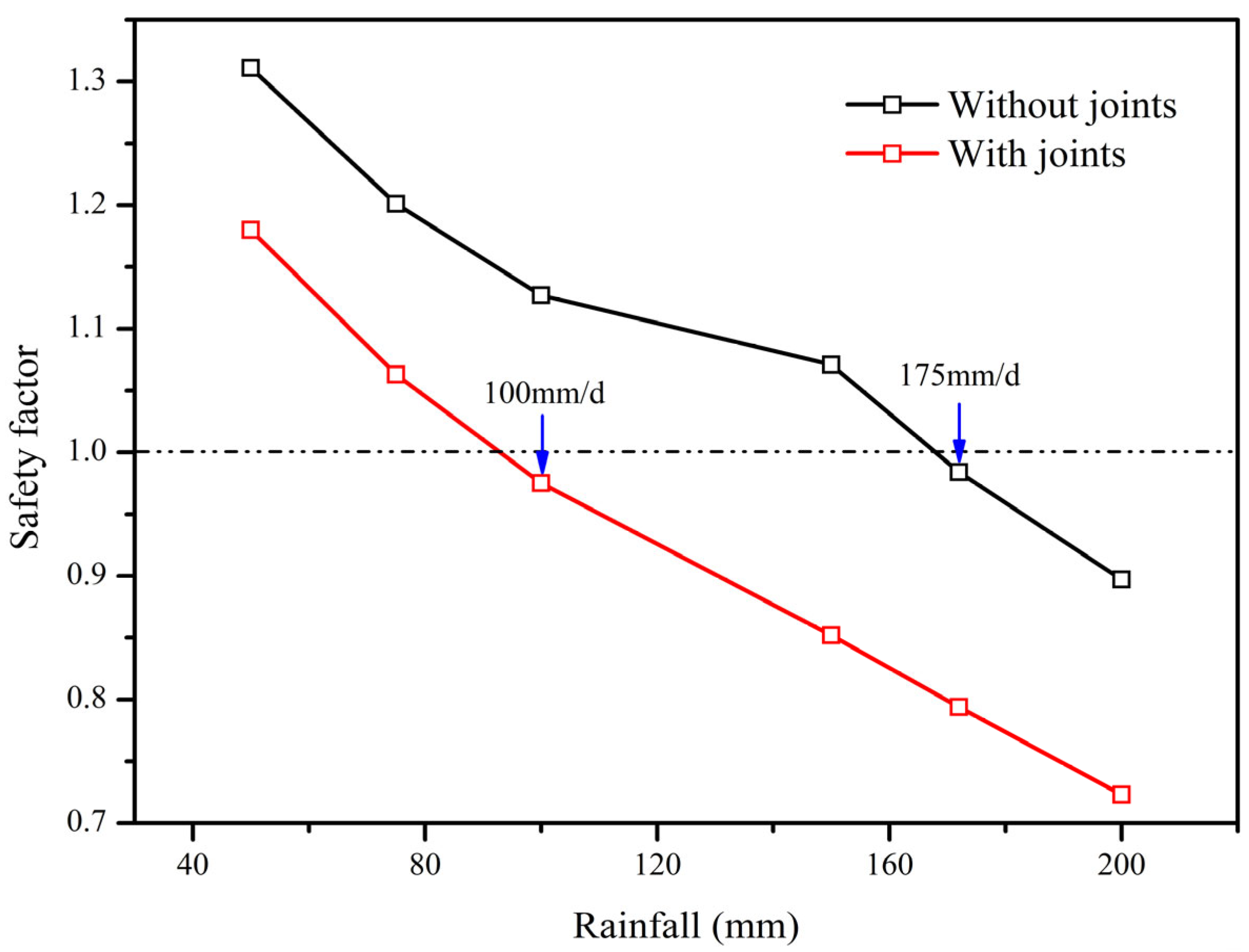

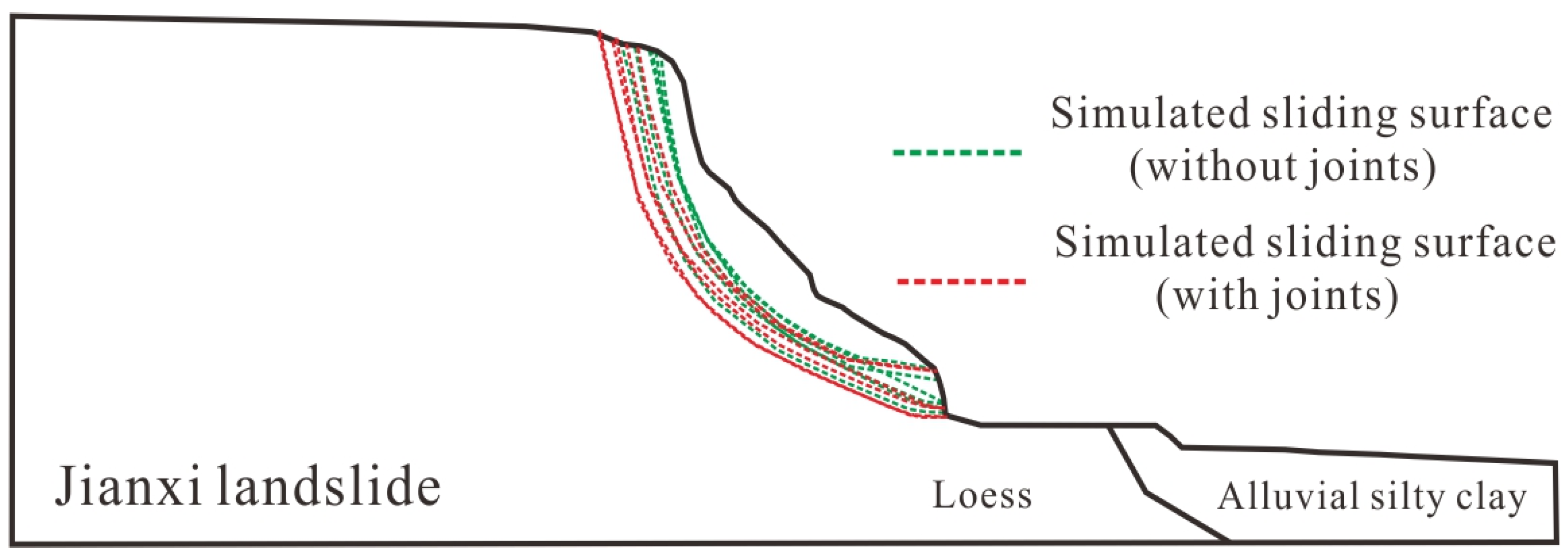

4.2. Landslide Stability

5. Discussion

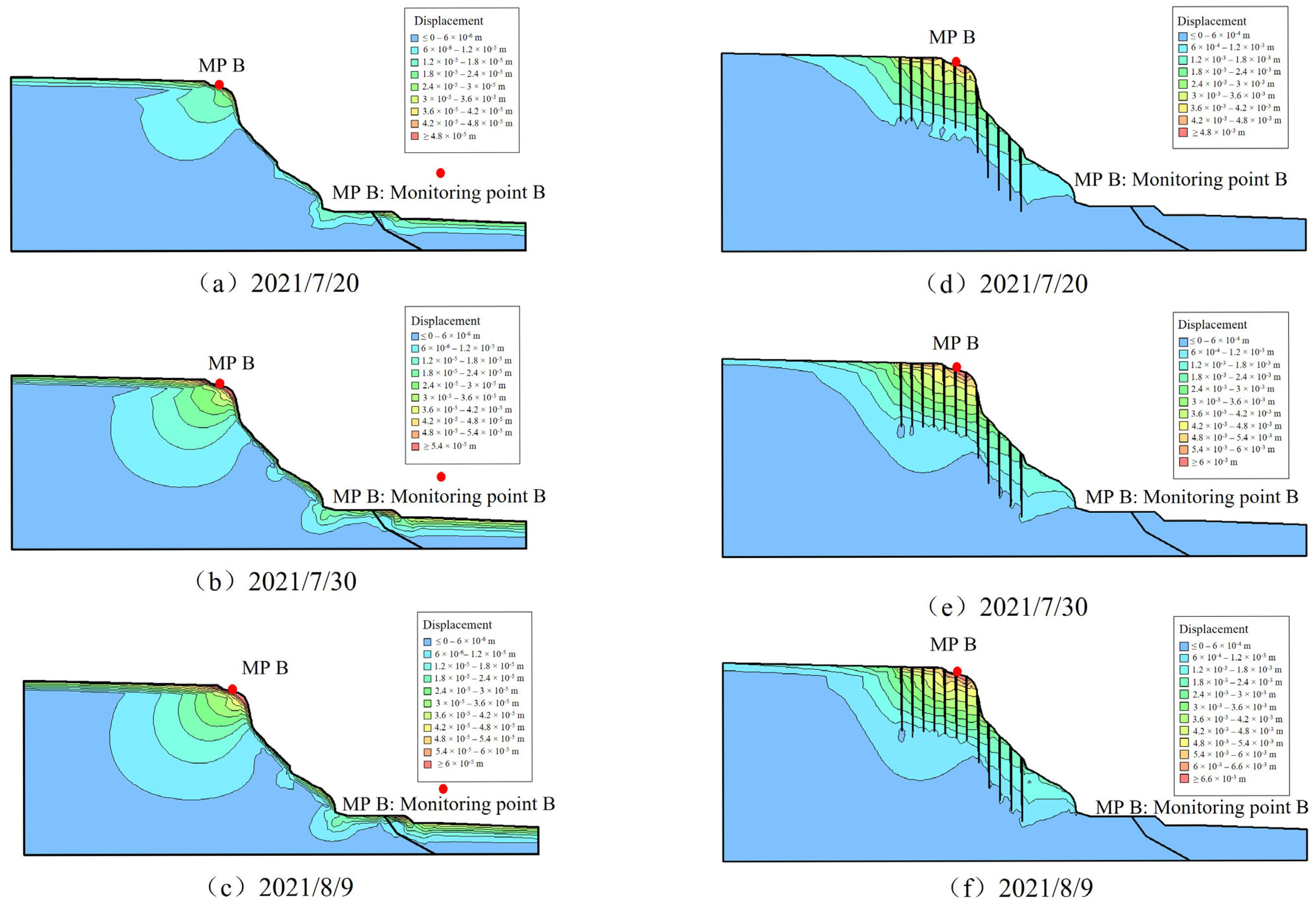

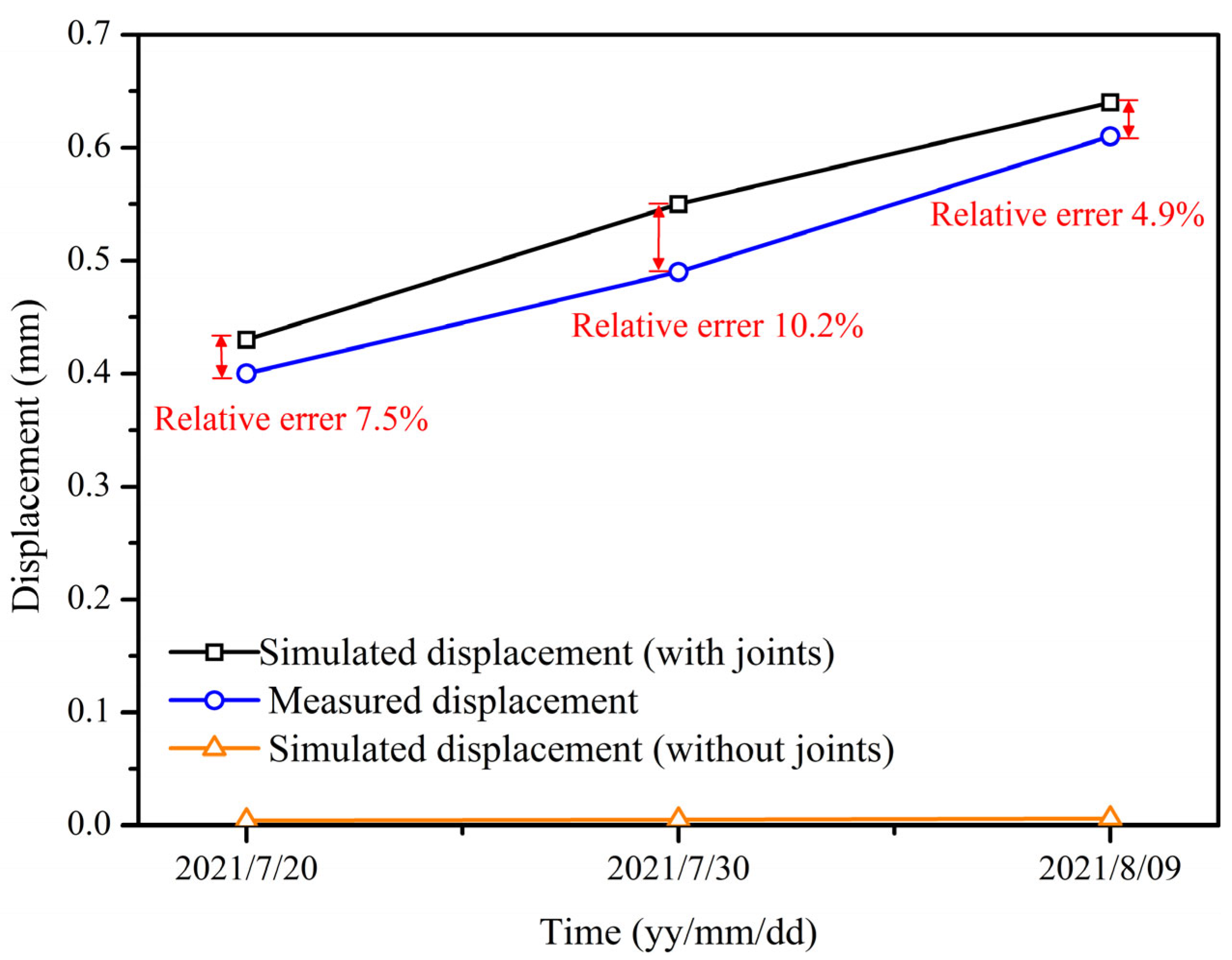

5.1. Validation of the Developed Model

5.2. The Influence of Joints on the Moisture Field and Stability of Jianxi Landslide

5.3. Novelty and Significance

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Mo, P. A unified landslide classification system for loess slopes: A critical review. Geomorphology 2019, 340, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Lin, H.; Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Jin, Z.; Liu, X. Development and evolution of Loess vertical joints on the Chinese Loess Plateau at different spatiotemporal scales. Eng. Geol. 2020, 265, 105372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wu, H.; Han, H.; Yan, Y.; Shi, B. Shear deformation calculation of landslide using distributed strain sensing technology considering the coupling effect. Landslides 2023, 20, 1583–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E. Geological hazards in loess terrain, with particular reference to the loess regions of China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2001, 54, 231–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Huang, Q.; Xu, W.; Han, Z.; Luo, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Q.; Sabri, S.M.M. Study on the interaction between pile and soil under lateral load in coral sand. Geomech. Energy Environ. 2025, 42, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Bai, M.; Gao, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zuo, M.; Liu, Q. Mechanism of rainfall-induced loess landslides revealed by multi-source data. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 9141–9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xia, Z.; Chen, D.; Miao, L.; Hu, S.; Yuan, J.; Huang, W.; Liu, L.; Ai, D.; Xu, H.; et al. Extreme Rainfall Events Triggered Loess Collapses and Landslides in Chencang District, Shanxi, China, during June–October 2021. Water 2024, 16, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Yang, X.; Yang, F.; Tao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Dong, J. Instability mechanism and control measures of loess slope induced by heavy rainfall. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2025, 50, e70088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, K.; Fenton, C.H.; Bell, D.H. A review of the geotechnical characteristics of loess and loess-derived soils from Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand. Eng. Geol. 2018, 236, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhang, F.; Peng, J.; Xu, C.; Kang, C.; Ma, P.; Fan, Z.; Leng, Y.; Li, C.; Cao, Y. A rainfall model test for investigating the initiation mechanism of the catastrophic loess landslide in Baqiao, Xi’an, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y. Model experimental study on the failure mechanisms of a loess-bedrock fill slope induced by rainfall. Eng. Geol. 2023, 313, 106979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, B. Analysis of the effects of vertical joints on the stability of loess slope. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Huo, A.; Zhao, Z.; Peng, J. Analysis of loess fracture on slope stability based on centrifugal model tests. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 3647–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yao, Y.; Wei, Z.; Meng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, H.; Zeng, R. Stability analysis of a loess landslide considering rainfall patterns and spatial variability of soil. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 167, 106059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Li, R.; Pan, J.; Li, R.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z. Measured rainfall infiltration and the infiltration interface effect on double-layer loess slope. Water 2023, 15, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.S.; Wu, L.Z.; Wu, S.R.; Li, B.; Wang, T.; Xin, P. Analysis of the causes of large-scale loess landslides in Baoji, China. Geomorphology 2016, 264, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, H.; Han, H.; Shi, B. Fiber optic monitoring of an anti-slide pile in a retrogressive landslide. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. 2024, 16, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, B.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Inyang, H.I. Kinematics, triggers and mechanism of Majiagou landslide based on FBG real-time monitoring. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.L.; Guo, Q.; Wu, J.Y.; Li, P.; Yang, H.; Zhang, M. Analysis of loess landslide mechanism and numerical simulation stabilization on the Loess Plateau in Central China. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 805–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wei, J.; Xu, C.; Shao, X.; Xu, S.; Chai, S.; Cui, Y. UAV survey and numerical modeling of loess landslides: An example from Zaoling, southern Shanxi Province, China. Nat. Hazards 2020, 104, 1125–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhu, S. Numerical runout modeling analysis of the loess landslide at Yining, Xinjiang, China. Water 2019, 11, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, G.; Cochrane, T.; Davies, T.; Bowman, E. Quantifying and modeling post-failure sediment yields from laboratory-scale soil erosion and shallow landslide experiments with silty loess. Geomorphology 2011, 129, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Z.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, P.; Shi, J.S.; Liu, G.G.; Bai, L.Y. Laboratory characterization of rainfall-induced loess slope failure. Catena 2017, 150, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Victor, C.; Duan, M. Research on the rainfall-induced regional slope failures along the Yangtze River of Anhui, China. Landslides 2021, 18, 1801–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Dong, Y.; Cui, L.; Zhou, L.; Luo, S. An integrated investigation of the failure mechanism of loess landslide induced by raining: From field to laboratory. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.B.; Kwong, A.K.L.; Dai, F.C.; Tham, L.G.; Min, H. Field monitoring of rainfall infiltration in a loess slope and analysis of failure mechanism of rainfall-induced landslides. Eng. Geol. 2009, 105, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, T.; Bjelajac, D.; Fitzsimmons, K.E.; Marković, S.B.; Basarin, B.; Mlađan, D.; Samardžić, I. Factors triggering landslide occurrence on the Zemun loess plateau, Belgrade area, Serbia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Feng, L.; Zhang, M.; Sun, P.; Li, T.; Liu, H. Application of resistivity measurement to stability evaluation for loess slopes. Landslides 2022, 19, 2871–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulamu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Shi, G.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, S. Triggering mechanics and early warning for snowmelt-rainfall-induced loess landslide. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.B.; Ye, T.L.; Zhang, X.H.; Cui, P.; Hu, K.H. Experimental and numerical analysis on the responses of slope under rainfall. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tu, G.X.; Huang, D.; Deng, H. Reactivation of a huge ancient landslide by surface water infiltration. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sun, P.; Wang, G.; Wu, L. Experimental and numerical study of shallow loess slope failure induced by irrigation. Catena 2021, 206, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.D.; Hou, T.S.; Guo, S.L.; Chen, Y. Influence of cracks on loess collapse under heavy rainfall. Catena 2023, 223, 106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, A.; Yazarloo, R.; Nabizadeh, F. Determining the failure mechanism and analyzing numerical stability of a Loess slope in seismic zones: A case study. Geopersia 2025, 15, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Peng, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, F. The mechanisms of a loess landslide triggered by diversion-based irrigation: A case study of the South Jingyang Platform, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 4945–4963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Sun, W.; Lan, H.; Bao, H.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Tian, C. Influence of tension cracks on moisture infiltration in loess slopes under high-intensity rainfall conditions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuchten, M.T.V. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Qian, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Seepage mechanisms and permeability differences between loess and paleosols in the critical zone of the Loess Plateau. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2021, 46, 2044–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, T.-H.; Liu, X.-J. Study on seepage character of loess vertical joint. Disaster Adv. 2013, 6, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Qian, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Tan, Y. Characteristics of water infiltration in the loess vadose zone: Evidence from electrical resistivity tomography. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, T. Increasing impacts from extreme precipitation on population over China with global warming. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mao, J.; Xiang, X.; Mo, P. Factors influencing development of cracking–sliding failures of loess across the eastern Huangtu Plateau of China. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stratum | Unit Weight γ (kN/m3) | Cohesion (Kpa) | Internal Friction Angle (°) | Permeability Coefficient K (cm/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural | Saturated | ||||

| Loess soil | 18.1 | 19.5 | 28.7 | 25.6 | 1.15 |

| Alluvial silty clay | 17.5 | 21.5 | 6.3 | 23.7 | 0.1 |

| Parameters | α | n | m | θs | θr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loess | 0.13 | 1.60 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.07 |

| Alluvial silty clay | 2.31 | 1.89 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.12 |

| Rainfall Intensity | Safety Factor | Change Rate of Safety Factor | |

|---|---|---|---|

| With Joints | Without Joints | ||

| 50 mm/d | 1.180 | 1.311 | 9.9% |

| 75 mm/d | 1.063 | 1.201 | 11.5% |

| 100 mm/d | 0.975 | 1.127 | 13.5% |

| 150 mm/d | 0.852 | 1.071 | 20.4% |

| 175 mm/d | 0.794 | 0.984 | 19.3% |

| 200 mm/d | 0.723 | 0.897 | 19.4% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, G.; Guo, H. Stability Analysis of Loess Slope Under Heavy Rainfall Considering Joint Effect—Case Study of Jianxi Landslide, China. Water 2025, 17, 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223271

Wang J, Zhang L, Zhao S, Li G, Guo H. Stability Analysis of Loess Slope Under Heavy Rainfall Considering Joint Effect—Case Study of Jianxi Landslide, China. Water. 2025; 17(22):3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223271

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jiahao, Lei Zhang, Shi Zhao, Guoji Li, and Haipeng Guo. 2025. "Stability Analysis of Loess Slope Under Heavy Rainfall Considering Joint Effect—Case Study of Jianxi Landslide, China" Water 17, no. 22: 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223271

APA StyleWang, J., Zhang, L., Zhao, S., Li, G., & Guo, H. (2025). Stability Analysis of Loess Slope Under Heavy Rainfall Considering Joint Effect—Case Study of Jianxi Landslide, China. Water, 17(22), 3271. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223271