The target aquifer of LFm in the Triassic system is defined as a tight sandstone inter-layered with mudstone [

27], with the distinct characteristics of low-porosity, low-permeability and certain brittleness [

28]. According to the groundwater level recovery test in the MC-1 well and water injection and mercury pressure tests in the laboratory, the hydraulic conductivity in the model is set at 3 × 10

−8 m/d and the porosity is 0.08 [

29]. The actual aquifer often exhibits heterogeneity and anisotropy, resulting in varying permeability and porosity. In order to depict the relationship between different aquifers and well types, the numerical simulations for three application scenarios of vertical, slanted and horizontal wells in the homogeneous isotropic aquifer, heterogeneous aquifer and fractured heterogeneous aquifer are conducted and presented in this paper.

3.1. Hydrodynamic Field in the Homogeneous Isotropic Aquifer

When there are no more detailed hydro-geological data and information of the deep target aquifer, the aquifer is generally assumed as homogeneous isotropic. It is an ideal state. The evolution of the hydrodynamic field not only provides the basis for well design but can also be used to give theoretical support for increasing injection capacity by artificial methods, such as the change in well configurations in aquifers.

Therefore, the vertical, slanted and horizontal wells in the homogeneous aquifer [

30] and their hydrodynamic field during continuous MWIS are shown in

Figure 3. The pressure of the wellhead is over 10 MPa. The groundwater pressure in the aquifer of LFm from the depth of −1800 m to −2299 m is up to 28–33 MPa. The length of the screen well for the vertical, slanted and horizontal wells are, respectively, 499 m, 735.1 m and 845.5 m.

The conical characteristic of the hydrodynamic field in the vertical well is clearly shown. Mine water flows through the homogeneous isotropic porous media. The liquid pressure forms a symmetrical distribution in the vertical cross-section while radiating outward from the wellbore. Similarly, the groundwater streamlines also radiate outward from the wellbore, with their influenced zones gradually expanding over time and forming an elevated-pressure region near the vertical wellbore. In low-pressure areas, groundwater streamlines gradually shift upwards, as shown in

Figure 3a. When the vertical well is transformed into a slanted well, the high-angle wellbore causes groundwater pressure distribution to remain centered on the wellbore. As time passes, the overall trend diverges significantly form the flow field characteristics of vertical wells described earlier and lacks symmetry, as shown in

Figure 3b. The area of its influenced zone is larger than the vertical well, resulting in a more extensive range of groundwater flow changes. This larger influenced zone means that the slanted well can generate a greater volume of groundwater, which has significant implications for MWIS. With a wider affected area, the slanted well can potentially be stored with a great deal of mine water in a larger region, enhancing overall water storage capacity. However, it also means that the impact on the surrounding groundwater environment and safety is more widespread. More pronounced changes in the groundwater pressure distribution caused by the horizontal well are more clearly shown in

Figure 3c. The altered groundwater flow patterns [

31] allow more mine water to migrate into a larger area. Storage capacity estimates in horizontal wells is subject to more uncertainty and complexity than comparable estimates in vertical and slanted wells. The radial symmetry usually present in the vertical well (

Figure 3a) does not exist. The wellbore storage effects are more significant in the early stage, as shown in

Figure 3(c1). Moreover, the elevated-pressure region around the horizontal wellbore leads to more zones of complex interactions between the well and the surrounding LFm. This also suggests that within a specific volume of a low-porosity and low-permeability aquifer, the storage of a greater quantity of mine water necessitates the continuous enlargement of the aquifer’s storage capacity. This implies that an elevated fluid pressure must be exerted to trigger hydraulic fracturing.

In addition, the effective trajectory of a horizontal well entering the LFm is significantly longer than that of vertical or slanted wells, resulting in a larger contact area with the aquifer. This greatly expands the water storage sweep extent, facilitates a more uniform migration front and stable pressure propagation, and mitigates pressure gradient-induced pore structure evolution. Consequently, it enhances the utilization efficiency of the LFm and helps maintain the relative stability of the mine water sealing medium.

Groundwater pressure distribution of different nodes is conducive to revealing the long-term change characteristics of MWIS. Three points at horizontal offsets of 200 m, 400 m and 600 m from the buried depth of 2299 m, as well as three nodes at vertical depths of −1850 m, −2050, and −2250 m at a horizontal distance of 200 m from the drilling hole are depicted in

Figure 4. During MWIS, the rate of groundwater pressure rise increases with proximity to the wellbore, while pressure buildup occurs more slowly at greater distances, as shown in

Figure 4a. Different buried depths are characterized by different fluid pressures. In the vertical well, the fluid pressure increases with burial depth, exhibiting a linear relationship with depth as shown in

Figure 4b. But it is different in the application of slanted and horizontal wells [

32]. As shown in

Figure 4c,d, the closer the nodes are to the wellbore, the faster the fluid pressure rise.

The rapid pressure surge of the point (400, −2999) as shown in

Figure 4c, may originate from rapid fluid recharge or the sudden connection of fracture systems, leading to localized stress redistribution. This indicates that mine water is in an unsteady transport state within the LFm, potentially triggering micro-fracture propagation or inducing seismic activity. Persistent recurrence of similar transient pressurization processes may induce long-term cumulative effects that compromise the mechanical stability of surrounding rock and elevate leakage risks. Such transient pressure anomalies can alter local pore structures and influence fluid seepage pathways and reservoir connectivity, thereby modifying recharge efficiency and distribution patterns. This pore restructuring driven by transient pressure may promote the development of secondary fractures and enhance local permeability, but could also trigger channelized flow, undermining containment security. Consequently, integrated analysis with the regional tectonic stress field suggests these phenomena may be closely linked to deep-seated fluid upwelling, necessitating vigilance against their chain reactions in mine water geological storage.

Regardless of how the shape or position of the wellbore changes, the groundwater flow lines always radiate outward from the wellbore, with the wellbore as the center. This results in faster pressure rise at the nodes closer to the wellbore, which gradually increases over time after reaching a steady state. In contrast, nodes farther from the wellbore experience slower pressure buildup. Therefore, the horizontal nodes from the horizontal well possess similar overall curve characteristics, as shown in

Figure 4e. The vertical nodes with different buried depths are able to be influenced by the elevated-pressure region. However, the pressure values at node (200, −1850) are generally lower than those at the other two nodes, due to the relatively limited influence from fluid over-pressure and shallow burial depth, as shown in

Figure 4f. From the pressure curve variations at horizontal or vertical nodes, it can be observed that in the homogeneous isotropic aquifer, the wellbore trajectory and the inherent fluid pressure distribution of the LFm govern the pressure distribution patterns and flow line characteristics [

33] during MWIS. This interesting understanding can provide a useful solution for the design of wells in MWIS projects.

3.2. Hydrodynamic Field in the Heterogeneous Aquifer

The preceding content discussed is based on the homogeneous isotropic aquifer, which can be utilized in scenarios with limited hydrogeological data or large-scale simulations. However, actual formations or aquifers are invariably anisotropic and heterogeneous, particularly in well-scale simulations where heterogeneity must be accounted for. The temporal evolution of hydrodynamic fields in a heterogeneous porous medium will exhibit distinctly divergent characteristics.

To account for the anisotropy and heterogeneity of the aquifer, the permeability data generated using the Gaussian distribution function in MATLAB was incorporated into COMSOL Multiphysics [

34]. The permeability values range from 10

−10 to 10

−3 m/d, with a mean of approximately 10

−7.5 m/d and a variance of 1. The contrast between

Figure 3 and

Figure 5 indicates that a similar whole tendency of groundwater pressure distribution and flow lines in the vertical, slanted and horizontal wells. Due to the heterogeneity of the aquifer, groundwater pressure contour lines are no longer smooth curves, and the directions of groundwater flow lines also diverge. This divergence in

Figure 5 is mainly caused by the variation in permeability within the heterogeneous aquifer. Areas with higher permeability allow for faster groundwater flow, resulting in more rapid pressure changes and more scattered flow lines. In contrast, regions with lower permeability impede the flow of groundwater, leading to slower pressure buildup and more concentrated flow lines.

In the vertical well of the heterogeneous aquifer, as shown in

Figure 5a, the pressure contour lines near the wellbore are more irregular compared to those in the homogeneous isotropic aquifer in

Figure 3a. Evaluation of data from the vertical wellbore generally centers on a single flow regime, such as infinite-acting radial flow. However, the groundwater flow lines of

Figure 5a are also more chaotic, indicating that the heterogeneous permeability has a relatively significant impact on the local flow pattern, especially in the small-scale scenario of the simulation. The evolution of the groundwater pressure field and flow lines shows that the influence of heterogeneity becomes more pronounced over the period from 0.3, 1, 3 to 5 years.

The orientation of the slanted wellbore in the heterogeneous aquifer further complicates the pressure distribution and flow patterns, as shown in

Figure 5b. The non-uniform permeability along the wellbore path causes the pressure to enhance unevenly. The flow lines deviate from the radial pattern observed in the homogeneous case, and the areas with high-permeability zones act as preferential flow paths or channels, causing the mine water to flow in a more complex and less predictable manner.

In the horizontal well of the heterogeneous aquifer (

Figure 5c), the long-distance horizontal wellbore traverses different permeability zones. This results in a highly variable pressure distribution along the wellbore. The flow lines near the wellbore are strongly influenced by the local permeability. In some high-permeability areas, the mine water can quickly spread laterally, while in low-permeability areas, the pressure rises slowly and the flow is restricted locally.

These characteristics of the hydrodynamic field in the heterogeneous aquifer are crucial for understanding the long-term behavior of MWIS, especially in water pressure and water balance. The non-uniform pressure distribution and complex flow patterns can affect the efficiency of injection, storage capacity, the distribution of mine water in the aquifer, and the potential for hydraulic fracturing. Therefore, when the design of MWIS projects in heterogeneous aquifers is conducted, it is necessary to take into consideration the influence the heterogeneity of the aquifer on the hydrodynamic field to optimize the well design and ensure the success of the project.

The nodes from three scenarios in the heterogeneous aquifer (

Figure 6) display similar trends to those shown in

Figure 4. However, due to the heterogeneity of the aquifer, the fluctuations of the initial stage in the groundwater level are more pronounced. The groundwater pressure of the vertical well from horizontal and vertical points experiences more significant rises and falls compared to the homogeneous case, as shown in

Figure 6a,b. This is because the variable permeability in the heterogeneous aquifer causes uneven water flow and pressure changes. High-permeability areas allow mine water to flow more freely, resulting in rapid drops in the groundwater pressure when water is being injected, while low-permeability barriers lead to slower mine water migration and more gradual changes in the groundwater pressure (

Figure 5). In the slanted well (

Figure 6c,d), the orientation of the wellbore combined with the heterogeneous permeability makes the groundwater pressure changes even more complex. The sudden increase in the red line for the point at (400, −2999), as shown in

Figure 6c, is similar to that in

Figure 4c. Heterogeneity causes deflection of fluid migration paths in porous media, thereby inducing local steep variations in the pressure field. This effect is consistent with Darcy’s Law, which elucidates the intrinsic relationship between permeability and pressure gradient. The groundwater pressure of partial points is obviously lower than others. For the horizontal well (

Figure 6e,f), the long-distance wellbore passing through different permeability zones in the aquifer has a major impact on the groundwater pressure compared to the slanted well. The initial increase in pressure is also more pronounced than that in the homogeneous aquifer. This means that the groundwater pressure response and increase will be faster in the heterogeneous aquifer. We also find that the mine water flow patterns for Darcy and Forchheimer flow is similar in homogeneous and heterogeneous porous media. This will have important implications for MWIS projects. If aquifers are considered homogeneous, the results of water storage capacity calculations will be overestimated.

3.3. Hydrodynamic Field in the Fractured Heterogeneous Aquifer

The difference in hydraulic conductivity is the external expression of heterogeneous aquifer and it stems from the fractures’ behaviors within the aquifers. Based on the logging data, core samples and ultrasonic imaging results from the LFm of the MC-1 well, we find that vertical fissures and horizontal bedding serve as the primary preferential flow paths.

The developed vertical fractures in the sub-layers of LFm are conducive to connecting with different vertical sub-layers, as shown in

Figure 7a. Macroscopically, the interbedded structure effectively controls mine water migration, while microscopically, fracture, interface effects and heterogeneity intensify local retention. This structure regulates the propagation direction and connectivity of hydraulic fractures, easily inducing stress shielding effects. Fracture development tends to deflect or become restricted by heterogeneous mudstone barriers, resulting in significant pressure gradient differences during the lateral migration of mine water between layers. Although the alternating arrangement of sandstone and mudstone improves the mine water storage stability of the groundwater system, it reduces vertical hydraulic conductivity. This leads to slow pressure dissipation during the geological storage of mine water, thereby affecting long-term sequestration efficiency and storage capacity. The average thickness of sub-layers is about 4.35 m. Many gas exploration wells revealed that drilling fluid loss was common when drilling into this formation [

25]. The horizontal fractures is the dominant role of bedding in the LFm, as shown in

Figure 7b,c. The temperature of backwater from the MC-1well after being stored for 2 years is about 64 °C to 65 °C, which indicates that its superior depth is from 2100 m to deeper. These features can provide storage pathways and effective space for MWIS. Therefore, the simulation of hydrodynamic field in the fractured heterogeneous aquifer is conducive to study the evolution of groundwater level, as shown in

Figure 8. The fracture networks in

Figure 8a–c were generated using MATLAB R2024a software based on the normal distribution function, with horizontal fracture lengths of 20 m and vertical fracture lengths of 5 m. Horizontal and vertical fractures constitute a fracture unit. The total number of fracture units in the simulation is 1000.

In comparison with

Figure 3 and

Figure 5, when the aquifer is heterogeneous with numerous fractures, the morphology of the hydrodynamic field becomes more complex and more susceptible to diffusion and migration in all directions, as shown in

Figure 8. The contrast with the hydrodynamic field, at the same time, indicates that the condition of aquifer heterogeneity plus fractures promotes the vertical wells, slanted wells and horizontal wells to exhibit greater mine water storage capacity. The simulation results of the heterogeneous aquifer in

Figure 5 and

Figure 8 conclusively demonstrate that fractures serve as preferential pathways [

35] for the rapid diffusion and migration of mine water, providing an efficient pressure release pathway for mine water. Meanwhile, areas with dense fractures exhibit lower groundwater pressure in

Figure 8, and sparsely fractured zones show higher groundwater pressure. Effective interconnection of fractures to form a hydraulically connected fracture network enables farther migration and diffusion of mine water while increasing storage capacity. Conversely, when fractures fail to connect effectively, the migration distance of mine water becomes restricted. Therefore, to extend the migration range of mine water, engineering methods should be employed to create artificial fractures, connect natural fractures effectively and generate an integrated fracture network. When artificial hydraulic fractures are not considered, mine water migrates and diffuses in all directions under the influence of a high seepage pressure differential. The greater the burial depth of the aquifer, the higher the water pressure, where fractures exhibit significant conductive effects, resulting in an overall dome-shaped morphology of the groundwater flow field. The fracture network can control the influence radius of mine water injection and storage, thereby magnifying the differences in hierarchic flow fields in geological anisotropy [

36].

The high pressure of MWIS induces an increase in the pore fluid pressure of the aquifer. This process causes the hydrodynamic field morphology to transition from radial diffusion to fracture-dominated heterogeneous flow. Fractures, especially the tensile fractures, provide ultra-low flow resistance pathways, enabling rapid migration of the vast majority of injected mine water through these conduits, which completely dominate the groundwater flow field morphology. Fractures partition the aquifer into high-velocity fracture flow zones and matrix low-velocity stagnant zones [

37], creating a strongly heterogeneous flow field. The fracture network facilitates long-distance, rapid pressure propagation along the fracture orientation, whereas pressure transmission perpendicular to fractures is slow and spatially limited, resulting in distortion of the hydrodynamic field.

High-pressure groundwater primarily propagates along the preferred pathways of fracture networks, forming elongated or finger-like invasion patterns rather than radially expanding into circular shapes. The spatial variations in fracture network connectivity, orientation and density significantly amplify the aquifer’s inherent heterogeneity [

38], leading to extreme complexity in hydrodynamic field morphology. It reflects the nonlinear and multi-scale nature of fractured media flow. Meanwhile, fractures partition the aquifer matrix into seepage units of varying scales. Flow within individual units is governed by the matrix, whereas inter-unit flow is controlled by fractures.

Fracture-dominated flow significantly enhances the influence radius [

39] of mine water injection and storage in low-permeability and low-porosity aquifers, which is critical for effective mine water injection. However, excessive formation heterogeneity can distort the groundwater flow field and reduce injection efficiency.

To comparatively analyze the influence of fractured heterogeneous aquifers on flow field patterns, this study acquired flow velocity time-series curves at various monitoring points for the slanted well in such aquifers, as shown in

Figure 8, along with more complex flow velocity contour maps of the horizontal well at different times, as shown in

Figure 9.

During mine water injection and storage, aquifer heterogeneity, including lithological variations, porosity and permeability distributions, as well as the development density and connectivity of fracture networks are the core factors governing flow field morphology. Different well configurations exhibit distinct pressure curve characteristics due to differences in their contact with the injected aquifer and groundwater injection pathways. These characteristics can intuitively reflect the evolutionary patterns of the flow field.

Figure 4 and

Figure 6 indicate that the groundwater pressure curves at the selected observation points in the numerical model generally exhibit an increasing trend with time, revealing that during mine water reinjection and storage, different wells display distinct flow field morphologies under the influence of aquifer heterogeneity and fracture networks. The dynamic changing characteristics of the pressure curves reflect the process by which the flow field is shaped by the combined effects of heterogeneity and fracture networks.

Based on the monitoring points in

Figure 4 and

Figure 6, velocity curves at six observation points were acquired, as shown in

Figure 9a, to investigate the variation patterns of groundwater flow velocity. Overall, the flow velocity exhibits a three-phase evolution: initial linear rapid increase, followed by nonlinear decrease, and finally progressive decline to a stable value in the mid-to-late stages. It is explicitly pointed out that under high-pressure gradients, the inertial forces and turbulence effects in fractured media are significantly enhanced, leading to the failure of the linear relationship assumed by Darcy’s Law. Under such circumstances, the flow velocity and pressure gradient exhibit nonlinear characteristics, necessitating the introduction of non-Darcy models. Under high-velocity conditions, local turbulence and inertial resistance within fracture channels are exacerbated, further deviating from the realm of Darcy’s linear seepage. Within 0.1 years of the simulation period, the deep low-permeability LFm has relatively sufficient storage space for mine water. The flow velocity at each monitoring point increases linearly, and the pressure also rises rapidly in a short time. By the end of the first year, the storage space in the deep sandstone aquifer is gradually filled with mine water. During this period, the groundwater flow velocity gradually decreases, and the storage space saturation and pressure stabilization are entered.

From the first year to the fifth year, the pore spaces and fractures in the deep sandstone aquifer within the wellbore influence radius were fully filled with mine water, forcing the water to diffuse outward to the surrounding areas via high permeability pressure differences. If discontinuous thin inter-layers or aquicludes exist in the targeted aquifer [

40], step-like pressure variations will occur. Therefore, the flow field morphology formed by long-term MWIS is generally similar to radial diffusion, consistent with Darcy’s Law. Affected by formation heterogeneity and fracture distribution, the flow velocity ranges at different observation points vary significantly, as shown in

Figure 9b,c. Therefore, if the aquifer has poorly developed fractures overall, it will lead to high pressure near the wellbore and low pressure in distant areas.

Nonuniform groundwater flow velocity fields [

41] are also observed, as shown in

Figure 10. The heterogeneity characteristic with permeability and porosity in the aquifer, play a crucial role in shaping these inhomogeneous flow velocity fields [

42]. In the fractured heterogeneous aquifer, the fractures act as preferential flow paths, causing the water to flow more rapidly with high velocity through these areas compared to the matrix, as shown in

Figure 10a. This leads to a significant difference in flow velocities between the fracture-dominated regions and the less permeable matrix regions. The presence of fractures not only affects the magnitude of the flow velocity but also the direction of the groundwater flow. High-pressure mine water tends to flow along the orientation of the fractures, which can deviate from the natural flow direction in a homogeneous aquifer. The results demonstrate that as the injection pressure increases, the flow front transitions from stable laminar flow to unstable fingering. Localized velocity disparities cause preferential expansion of seepage paths along low-resistance channels, leading to the formation of significant channelized flow. This deviation in flow direction can cause the formation of complex flow patterns, such as eddies and local flow stagnation zones, as shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 8 and

Figure 10b,c.

Moreover, the connectivity of the fracture network is another important factor. A well-connected fracture network allows for more efficient mine water flow, as it provides continuous pathways for the mine water to move through the aquifer [

43]. In contrast, a poorly connected fracture network may result in isolated pockets of mine water flowing around the wellbore, as shown in

Figure 10b,c, reducing the overall efficiency of the injection process. As for the lithological heterogeneity in the aquifer, it also contributes to the inhomogeneous flow velocity fields. Different rock types of the targeted strata have different hydraulic conductivities, which means that mine water will flow at different rates through them. For instance, sandstone aquifers may have higher hydraulic conductivity and groundwater flow velocity compared to shale layers. In addition, the interaction between the fractures and the lithological heterogeneity in the aquifer further complicates the flow velocity fields [

44]. Fractures that cut across different lithological layers can create complex flow scenarios, where mine water may be forced to change its flow path due to the difference in hydraulic properties of these layers. This can lead to the formation of local high-velocity zones and low-velocity zones, which have a direct impact on injection capacity and efficiency.

With the elapse of time, the inhomogeneous velocity fields [

45] are along the uneven distribution of the injected mine water within the aquifer. Therefore, understanding the factors that contribute to these inhomogeneous flow velocity fields is essential for optimizing the mine water injection process and ensuring the sustainable use of unconventional groundwater resources in mining areas.

3.4. Mine Water Storage Capacity

To accurately evaluate MWIS capacity in the aquifer of LFm, it is necessary to not only consider the above mentioned factors affecting the flow velocity field but also conduct a more comprehensive evaluation for MWIS. For the above mine water flow patterns, as shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 5 and

Figure 8, it is indicated that mine water specific capacity in the homogeneous aquifer of LFm exhibits distinct spatial distribution patterns contingent upon wellbore orientation. This variability stems from differential intersection geometries between the well and the aquifer’s saturated thickness and isotropic hydraulic conductivity, alongside flow convergence effects near the well screen. The radial flow convergence toward a fully penetrating vertical well generates a symmetric, axisymmetric yield distribution. The specific capacity scales linearly with the hydraulic conductivity and aquifer’s saturated thickness [

46] (Theis equation [

47]). Storage capacity diminishes radially outward, forming concentric equipotential surfaces. For the slanted well, the inclination introduces directional anisotropy in flow paths. Storage capacity distribution becomes elliptical, with higher flux along the dip direction of the well trajectory. The effective screen length projected onto the vertical plane governs capacity magnitude, while asymmetric increasing cones develop due to preferential flow along the well axis. As for the horizontal well, the linear flow regime [

48] dominates storage capacity, yielding a cylindrical flow geometry perpendicular to the well axis. Specific capacity is proportional to the hydraulic conductivity and screen length of the well [

49]. Storage distribution exhibits bilateral symmetry along the wellbore, with minimal vertical increasing penetration.

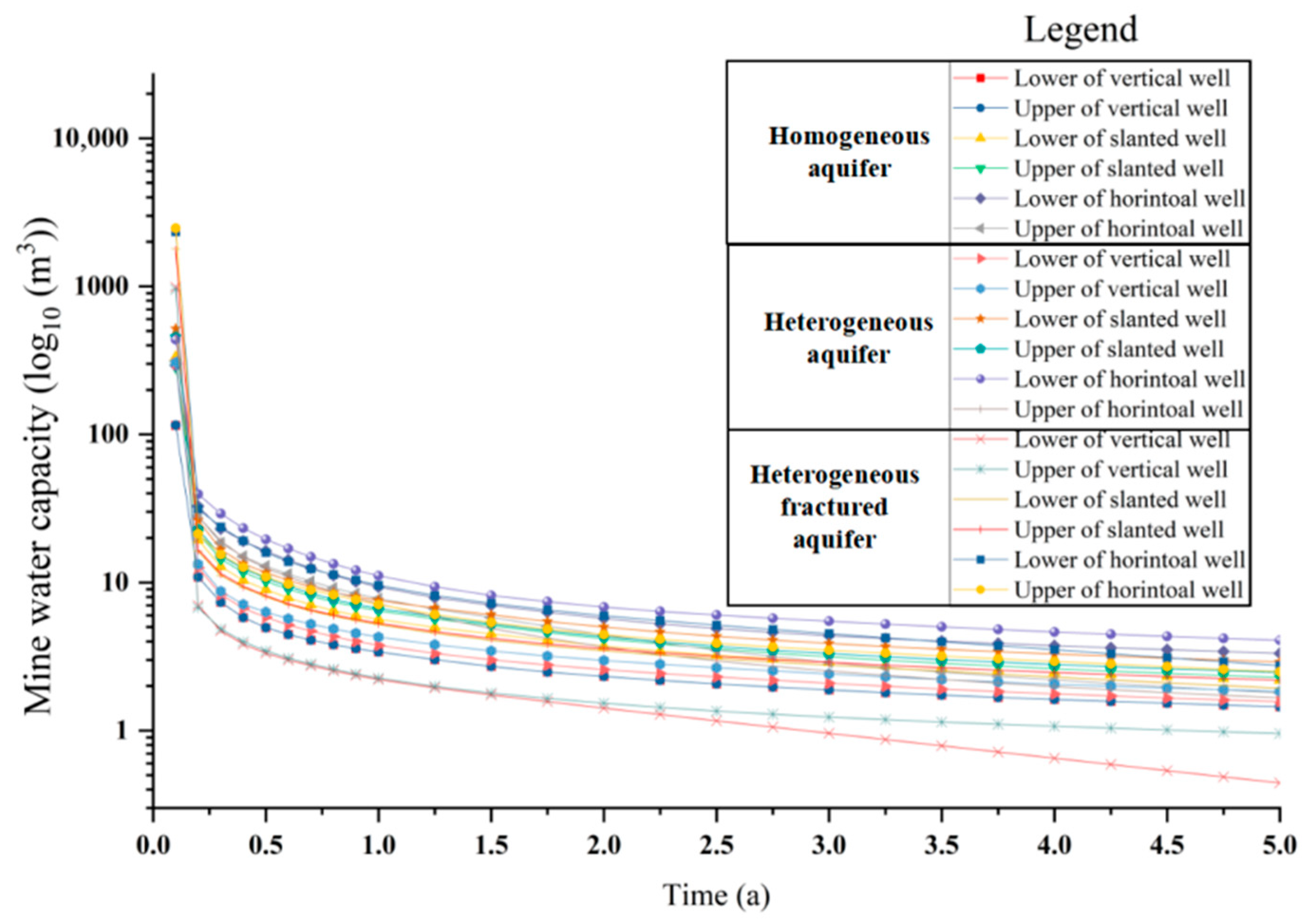

As shown in

Figure 11, in a homogeneous aquifer of LFm, MWIS capacities on both sides of a vertical well are equal. Slanted wells and horizontal wells store more water in the underlying strata than in the overlying strata. The overall water storage capacity follows the order: horizontal well > slanted well > vertical well [

50], with the capacities of slanted wells and horizontal wells being approximately 2.4 to 2.65 times that of the vertical well. For the heterogeneous aquifer, MWIS capacity on either side of a vertical well is asymmetric, governed by permeability heterogeneity. Both slanted and horizontal wells exhibit greater storage capacity in lower strata than in upper strata. It is consistent with the characteristic of the homogeneous aquifer. With the influence of heterogeneity, horizontal wells (≈slanted wells) exceed vertical wells by approximately 1.77 to 1.81 times in storage capacity. In a heterogeneous fractured aquifer, MWIS capacity on the left and right sides of a vertical well remain unequal. For the slanted well, the lower formation exhibits higher water storage than the upper formation, while conversely, horizontal wells show greater mine water storage in the upper formation compared to the lower. Overall, MWIS capacity follows the order: horizontal well (2.47 times that of vertical well) > slanted well (1.85 times) > vertical well. The mine water injection and storage project in the Nalinhe No.2 Coal Mine constructedthree wells, including vertical, slanted and horizontal wells in 2023 to 2024. The injection rates of mine water were stable at 96 m

3/h, 150 m

3/h and 210 m

3/h under the same water pressure conditions, respectively. The simulation results are in agreement with the on-site monitoring data, thereby validating the rationality of model parameterization and the effectiveness of boundary condition settings.

Based on the temporal trend of individual curves as shown in

Figure 11, the high permeability of formation pores and fractures resulted in mine water reserves exceeding 50% of the total storage capacity within 0.2 years [

51]. As time progressed, the mine water reserves in subsequent periods declined rapidly and gradually stabilized, indicating that the effective reserves within the well’s influence area became progressively saturated and showed a trend contrary to the rising water pressure. This is also verified by the flow rate of the engineering projects in the Nalinhe No.2 Coal Mine. Therefore, a non-aqueous fracturing technique [

52] for continuous increases in injection pressure are necessary to augment the mine water reserves by permeation.