An Integrated Methodology for Novel Algorithmic Modeling of Non-Spherical Particle Terminal Settling Velocities and Comprehensive Digital Image Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Software and Hardware Tools Used in the Algorithmic Study

2.2. Derivation of Empirical Settling Velocity Model for Non-Spherical Particles

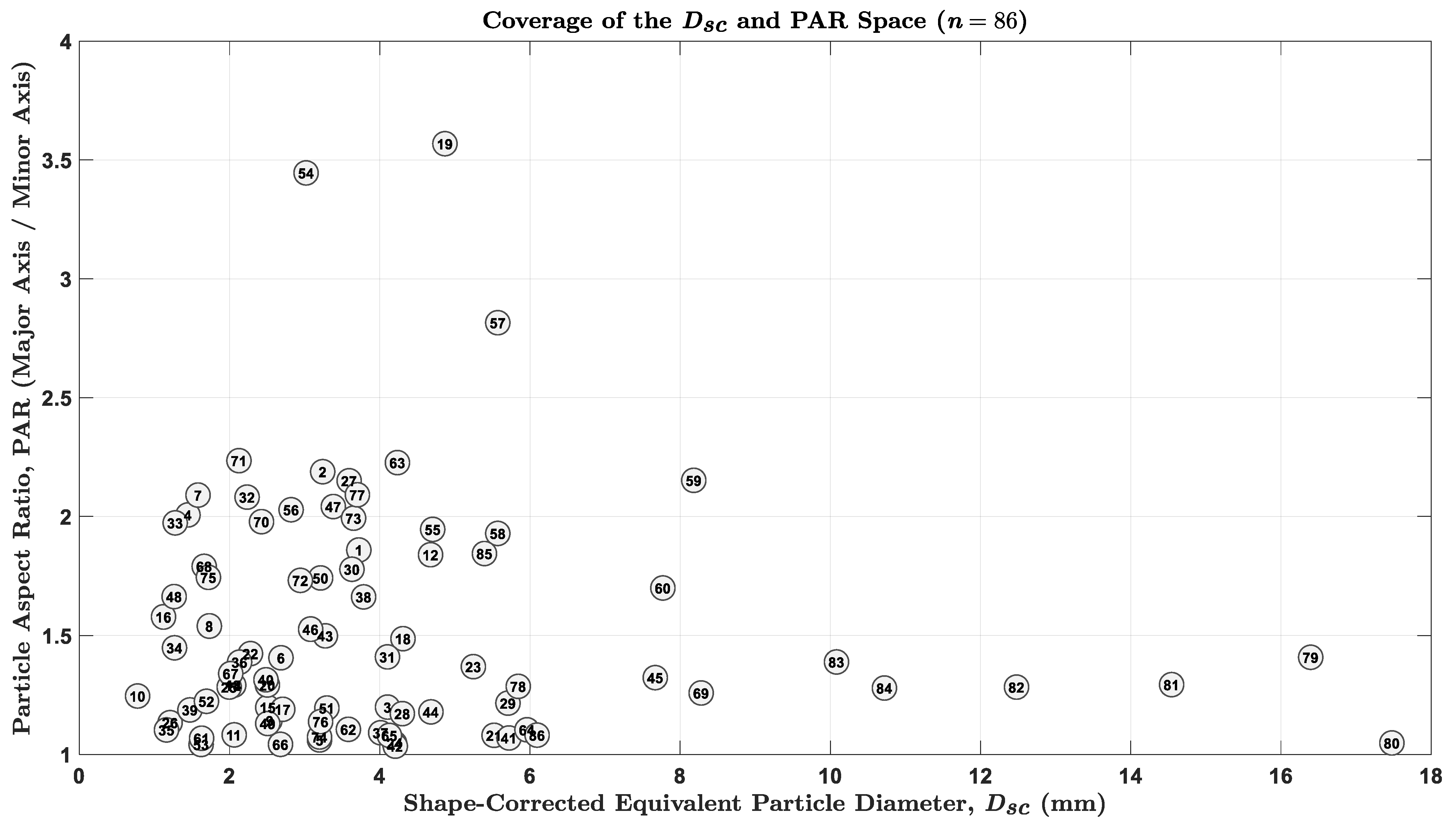

2.2.1. Domain of Primary Predictors Used in the Analysis

2.2.2. Numerical Generation of the Comprehensive Dataset

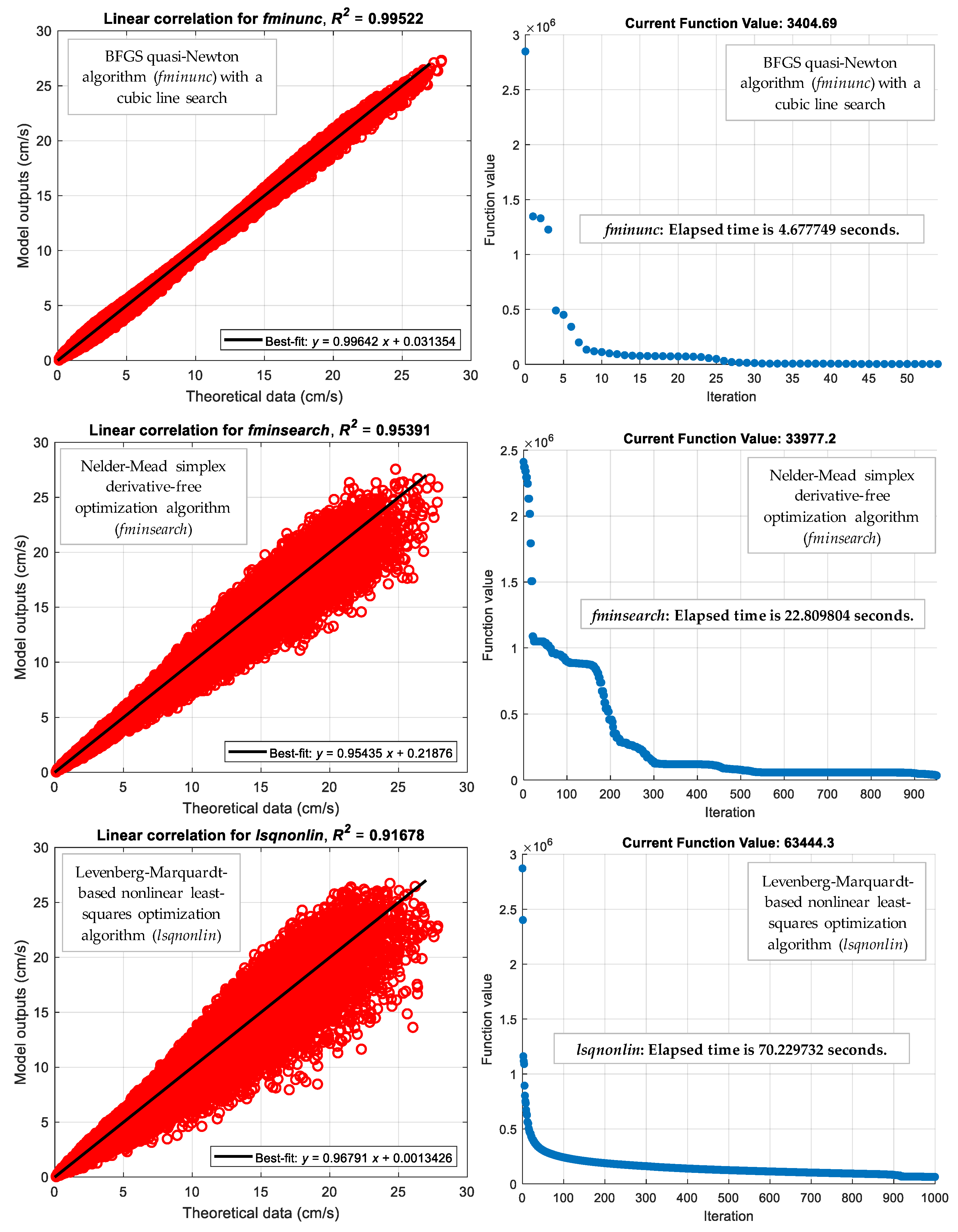

2.2.3. Algorithmic Model Development and Comparative Performance Evaluation

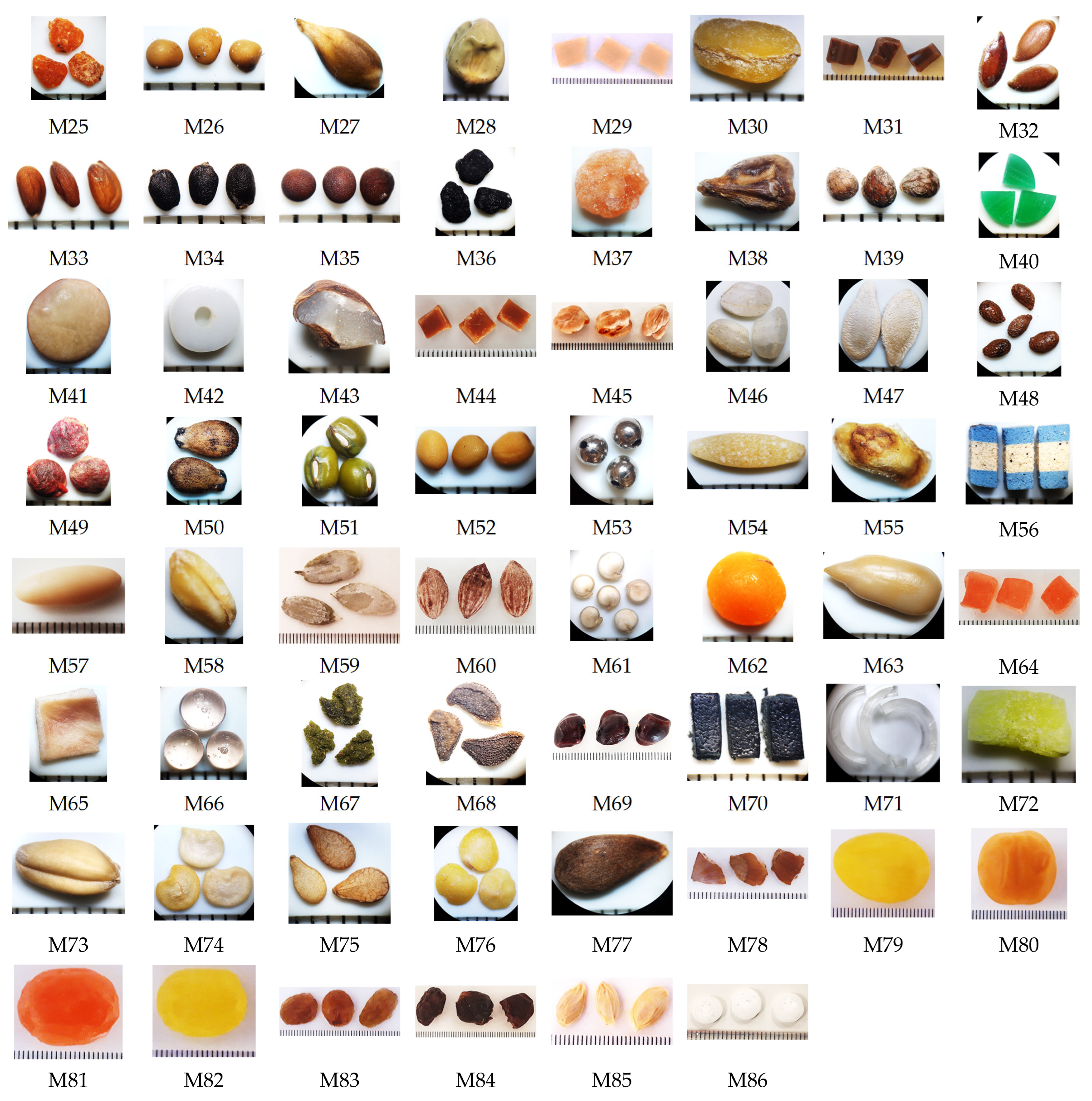

2.3. Irregular Particles Used in the Experimental Study

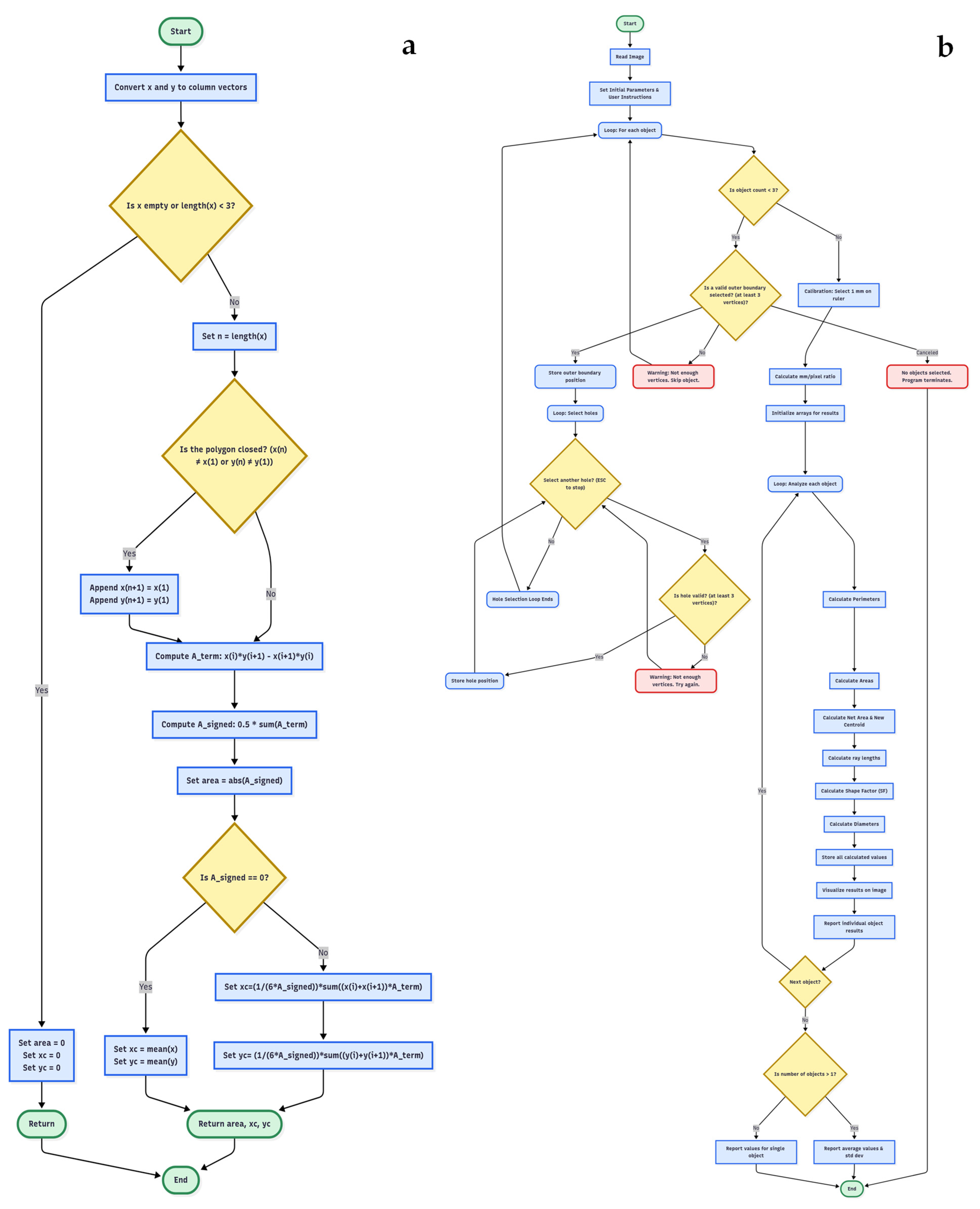

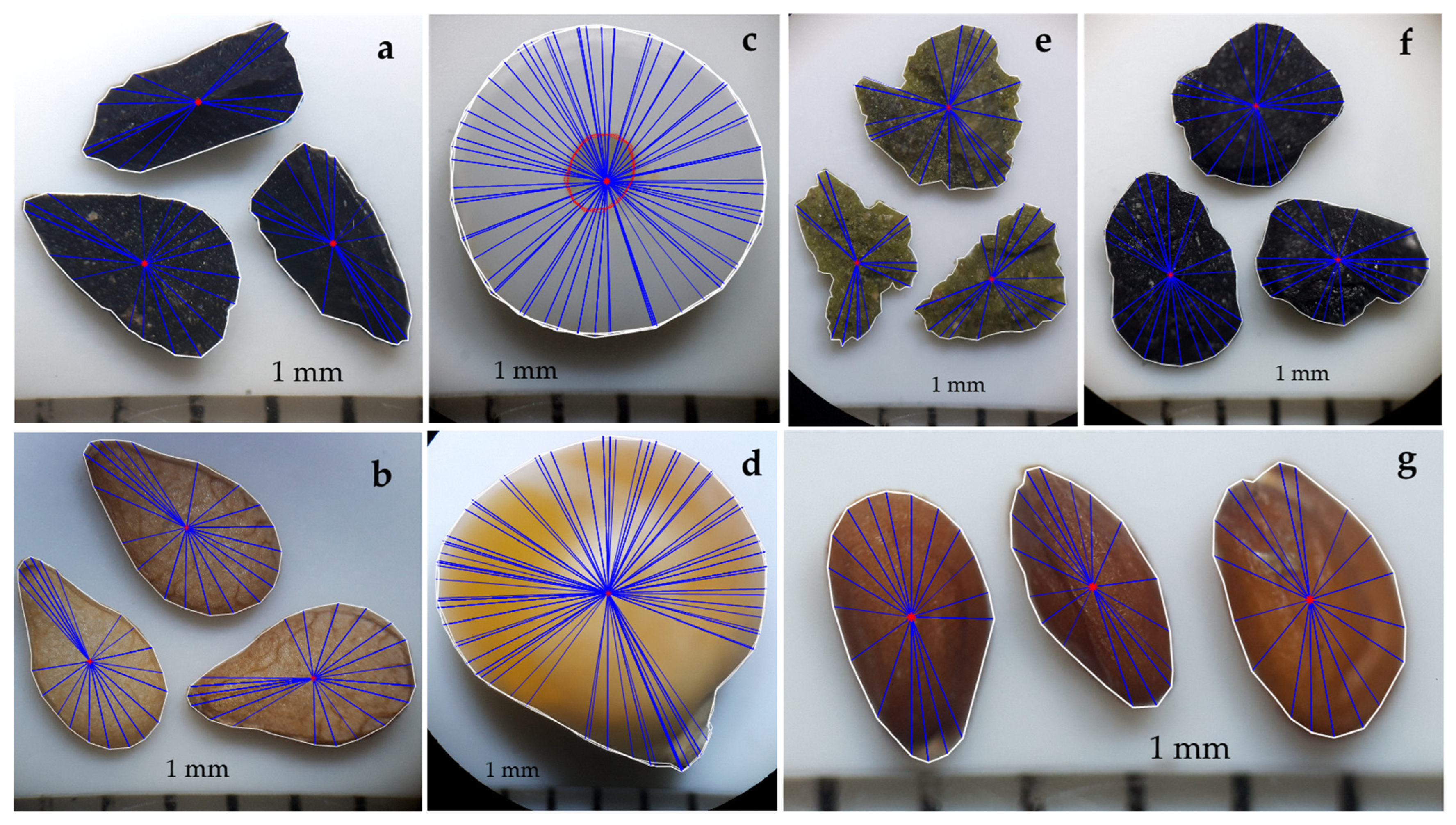

2.4. Digital Characterization of Irregular Particle Morphology and Geometry

- (a)

- Particle definition: The boundary of the target particle was manually defined using the interactive impoly tool, which was then converted into the binary pixel mask using the createMask function for the region of interest (ROI),

- (b)

- Area and centroid: The total pixel area and the geometric center (centroid) of the defined binary area were calculated (using the MATLAB® Image Processing Toolbox),

- (c)

- Moment calculation: The second central moments, representing the spatial distribution of the pixel area relative to the centroid, were calculated via the embedded functionality of regionprops,

- (d)

- Axis determination: These three moment values were mathematically processed to determine the orientation angle and the magnitude of spread for the equivalent ellipse,

- (e)

- Axis lengths: The spread magnitudes were converted into the final physical dimensions (major axis and minor axis lengths) which are subsequently used to calculate PAR as the ratio of the major axis length to the minor axis length.

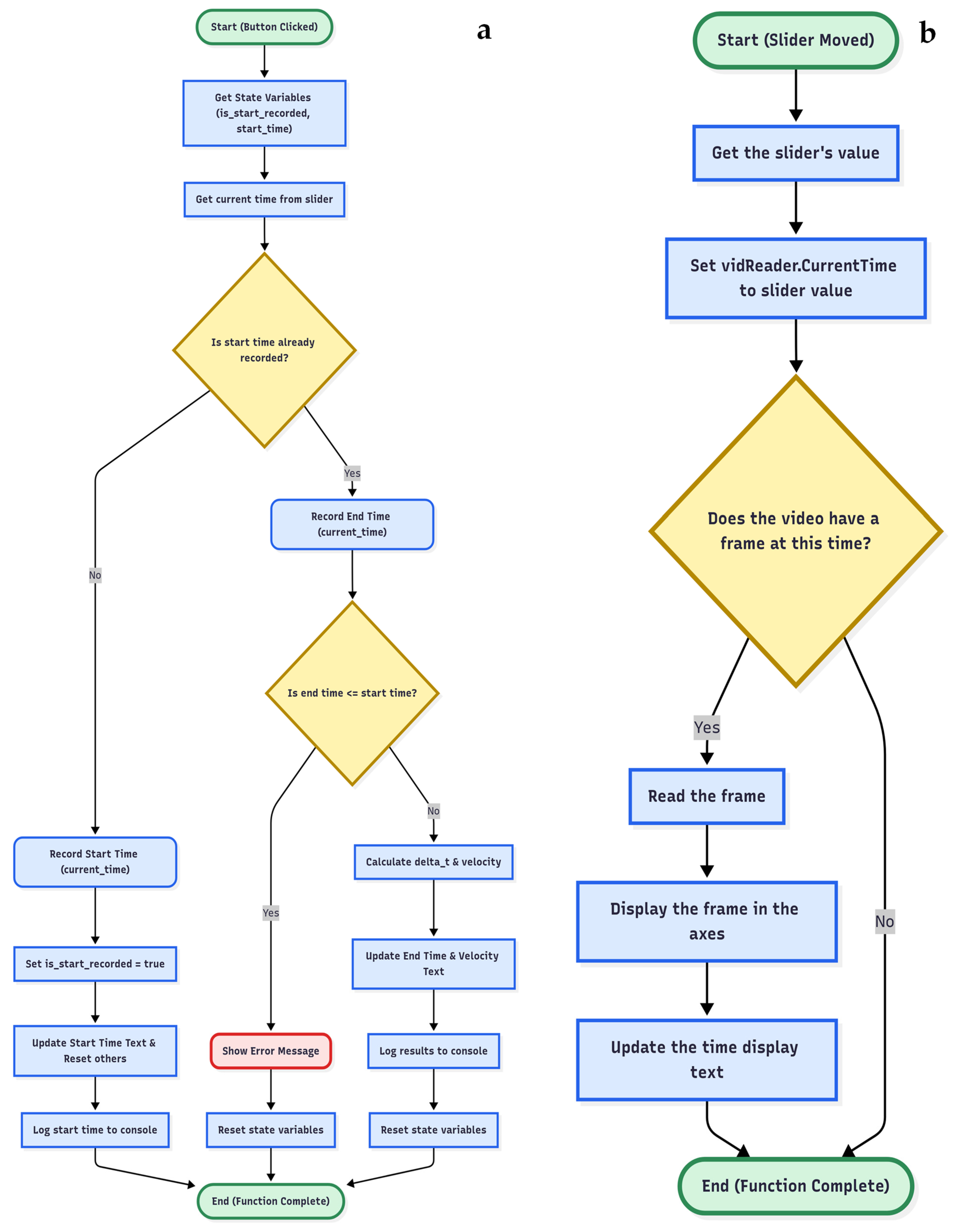

2.5. Experimental Setup for Measurement of Terminal Settling Velocity

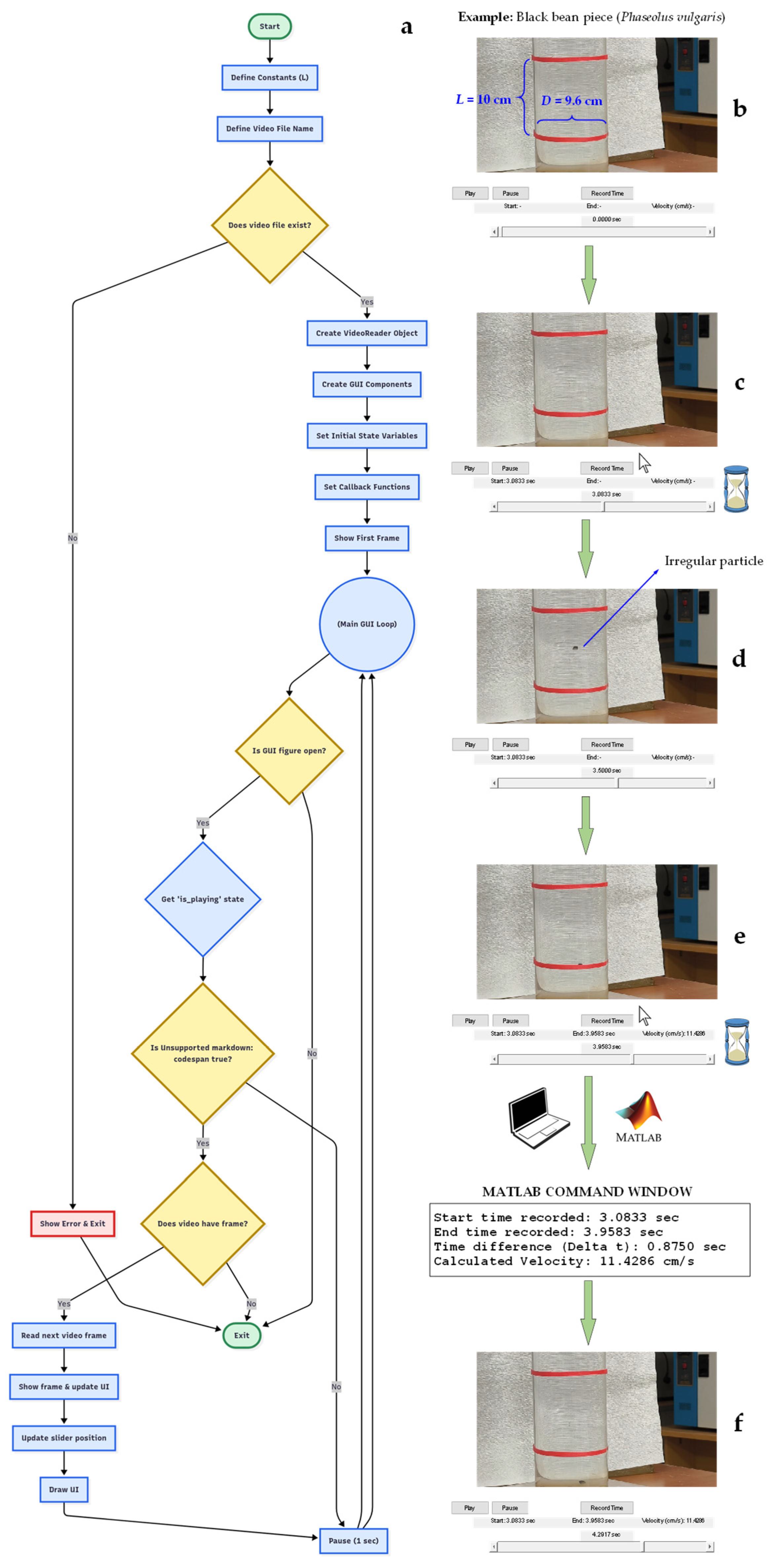

2.6. Graphical User Interface for Analyzing Real-Time Settling Dynamics

2.7. Representation of Statistical Performance Evaluators

3. Results

3.1. Morphological and Geometrical Characteristics of the Experimental Particles

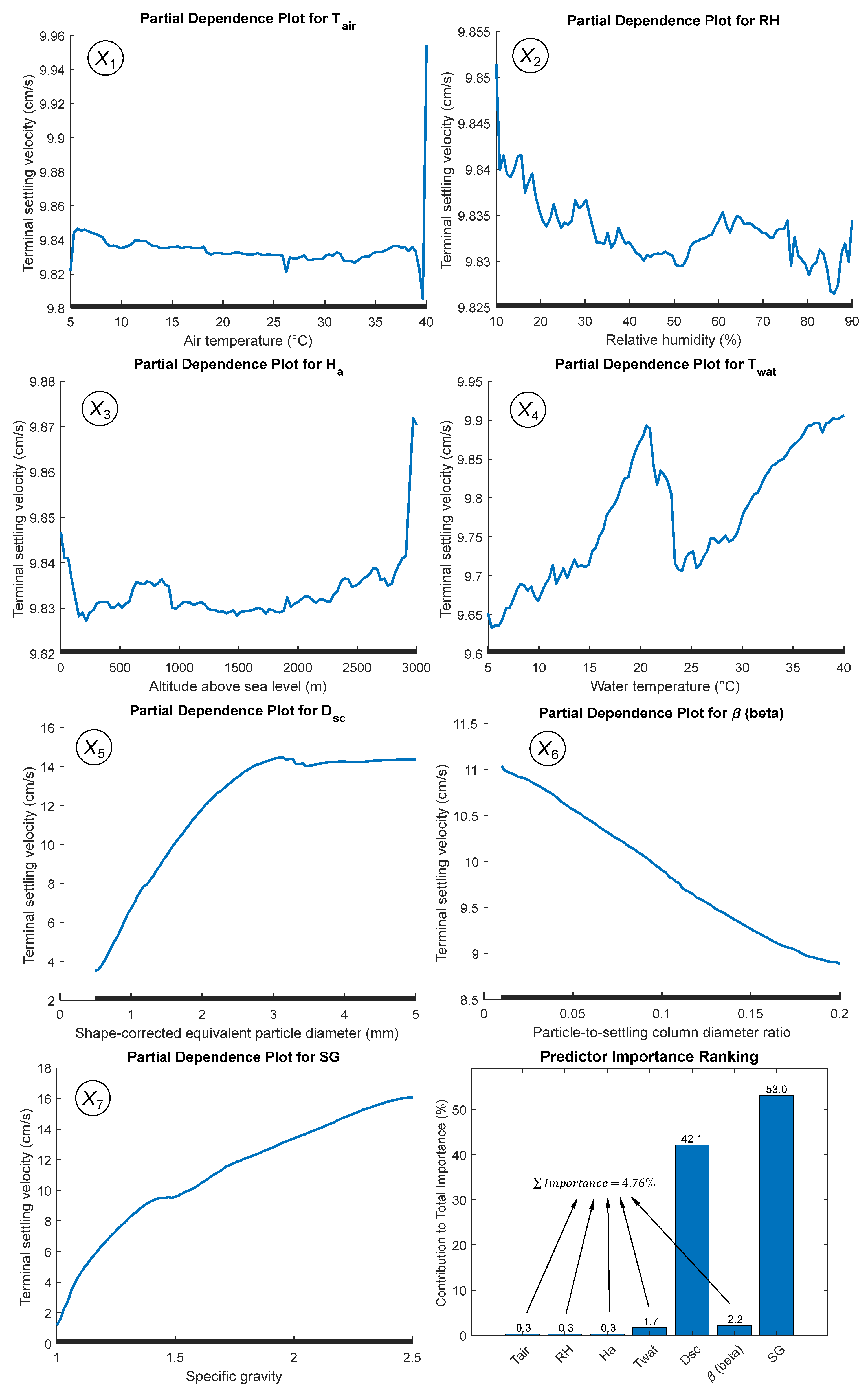

3.2. Model Optimization and Inter-Variable Relationships

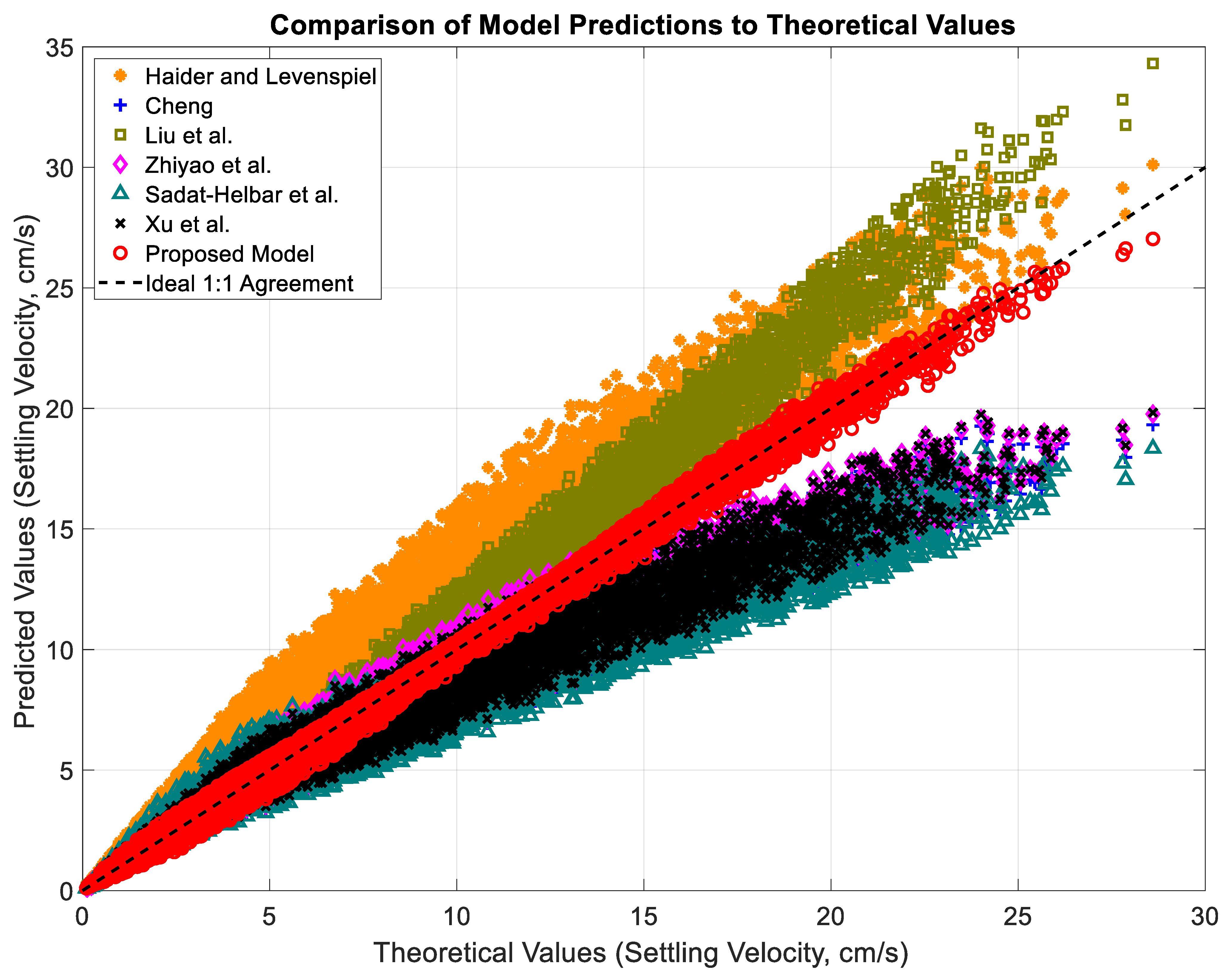

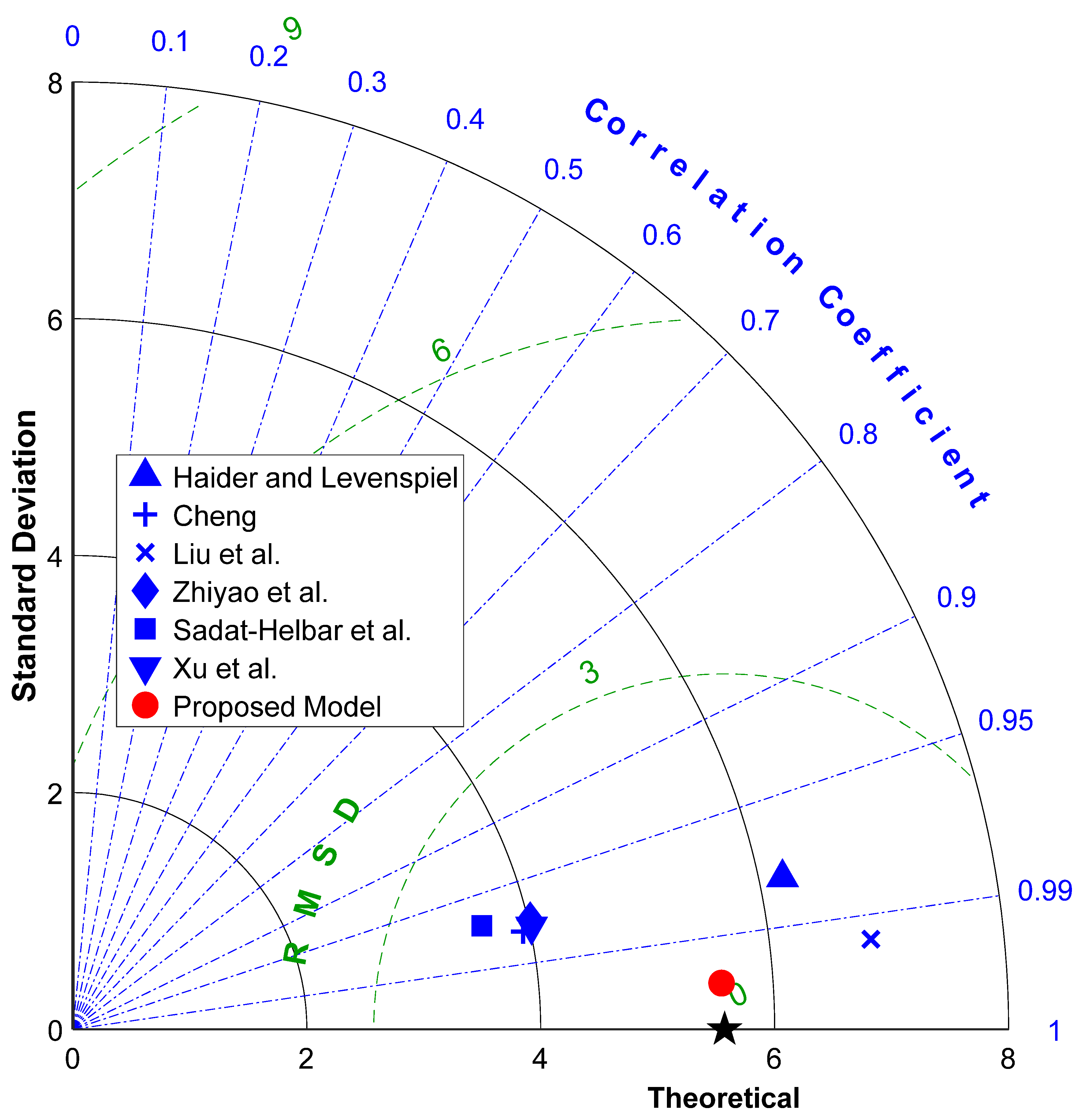

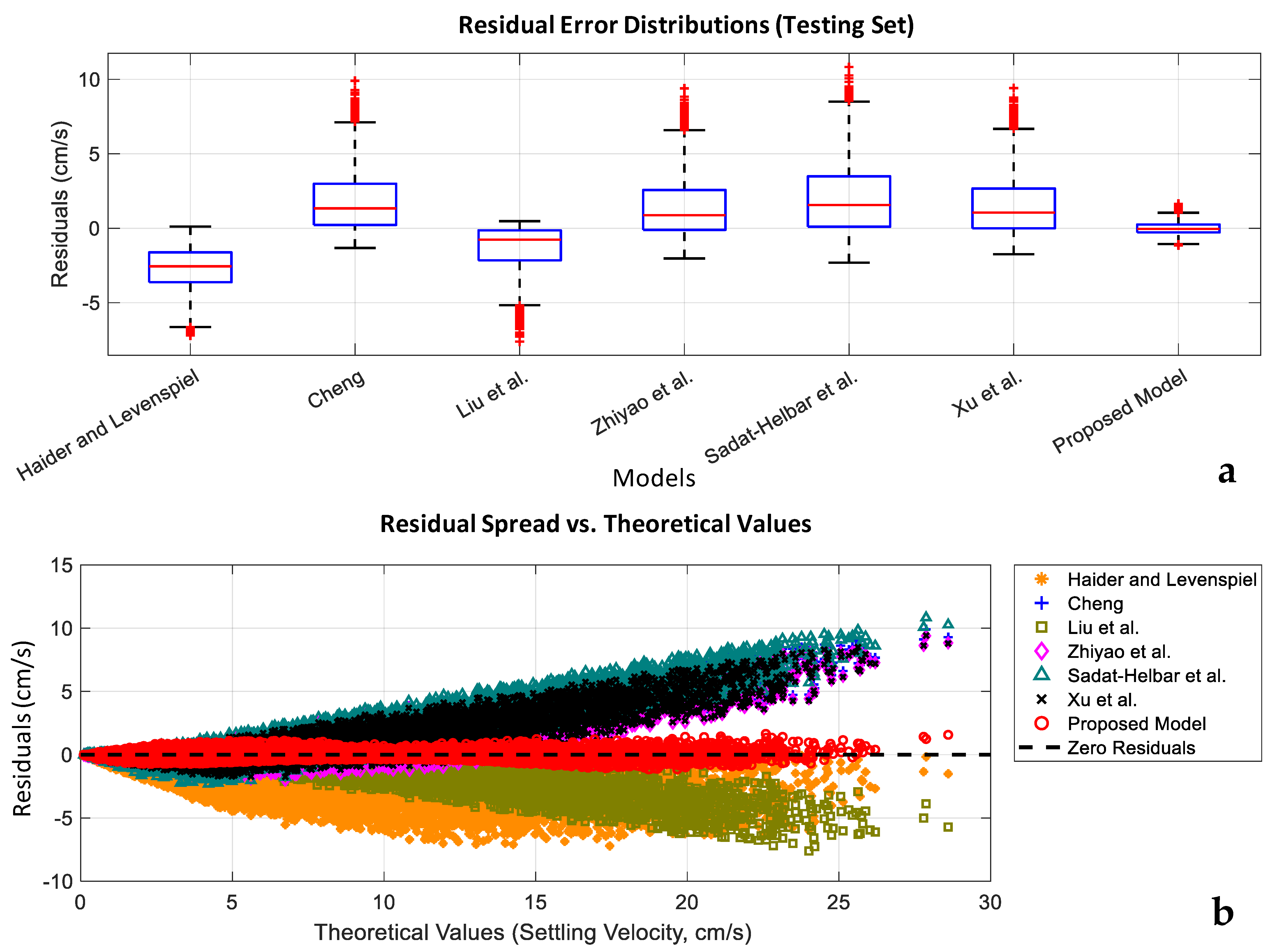

3.3. Comparison with Other Empirical Prediction Models

3.4. Appraisal of Prediction Accuracy via Statistical Metrics

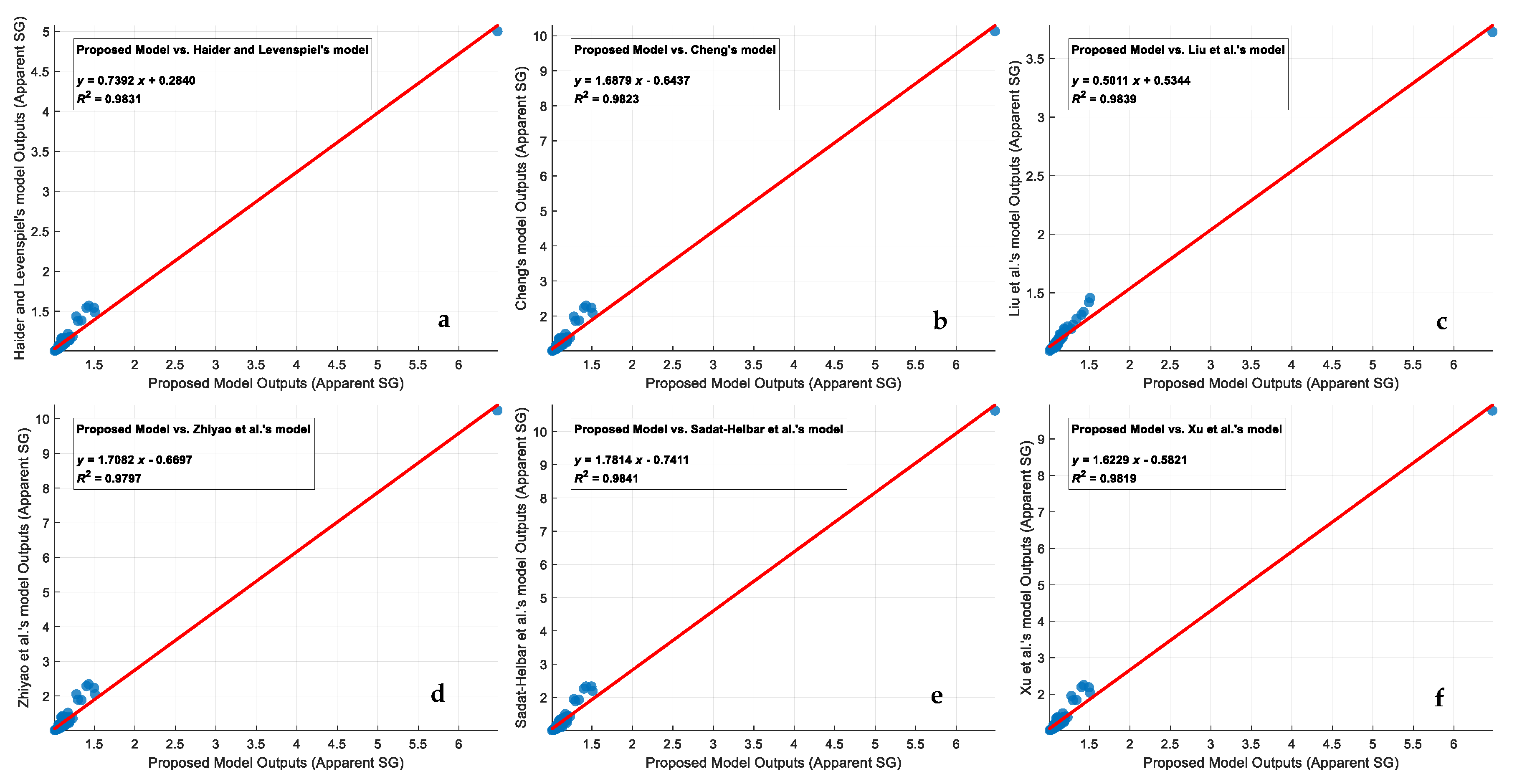

3.5. Development of Specific Gravity Database for Distinct Irregular Particles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Morphological and Visual Characterization of Irregular Particles Used in the Experimental Study

Appendix B. MATLAB®-Based Flowcharts: Computational Procedures and Interface Management for Irregular Particle Analysis

Appendix C. Morphological and Geometrical Parameters Derived from Comprehensive Digital Image Analysis

| Material Code | (mm) | (mm2) | SF (mm) | (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 17.7867 ± 0.0843 | 18.1139 ± 0.1087 | 0.2391 ± 0.0096 | 3.7212 ± 0.0294 |

| M2 | 17.4812 ± 0.0565 | 17.8561 ± 0.0396 | 0.6194 ± 0.0226 | 3.2398 ± 0.0157 |

| M3 | 17.8812 ± 0.0477 | 22.8829 ± 0.1337 | 0.2834 ± 0.0066 | 4.1031 ± 0.0226 |

| M4 | 7.5645 ± 0.3637 | 3.4310 ± 0.4560 | 0.2388 ± 0.0505 | 1.4459 ± 0.0901 |

| M5 | 12.8273 ± 0.8096 | 12.8810 ± 1.5903 | 0.1437 ± 0.0237 | 3.1977 ± 0.1660 |

| M6 | 12.9577 ± 0.2551 | 9.5171 ± 0.4683 | 0.1837 ± 0.0384 | 2.6842 ± 0.1175 |

| M7 | 8.4706 ± 0.7387 | 4.2136 ± 0.8877 | 0.2846 ± 0.0460 | 1.5798 ± 0.1582 |

| M8 | 8.2866 ± 0.5095 | 4.8510 ± 0.5256 | 0.2558 ± 0.0837 | 1.7304 ± 0.0483 |

| M9 | 10.8035 ± 0.6816 | 7.3351 ± 1.0401 | 0.0724 ± 0.0239 | 2.5364 ± 0.2117 |

| M10 | 3.3205 ± 0.0565 | 0.7933 ± 0.0266 | 0.0490 ± 0.0184 | 0.7749 ± 0.0457 |

| M11 | 7.8332 ± 0.5394 | 4.7931 ± 0.6604 | 0.0492 ± 0.0145 | 2.0615 ± 0.1606 |

| M12 | 38.9110 ± 0.4508 | 40.1293 ± 0.0914 | 1.7393 ± 0.2411 | 4.6762 ± 0.1129 |

| M13 | 11.6831 ± 0.6205 | 5.1529 ± 0.2591 | 0.1198 ± 0.0073 | 2.0425 ± 0.0542 |

| M14 | 9.4358 ± 0.3960 | 5.3993 ± 0.2267 | 0.1152 ± 0.0242 | 2.0551 ± 0.0102 |

| M15 | 10.0150 ± 0.1200 | 7.5839 ± 0.2461 | 0.0917 ± 0.0152 | 2.5080 ± 0.0774 |

| M16 | 5.0541 ± 0.1843 | 1.8471 ± 0.1536 | 0.1092 ± 0.0089 | 1.1202 ± 0.0462 |

| M17 | 11.2342 ± 0.3055 | 9.2334 ± 0.5969 | 0.1323 ± 0.0563 | 2.7075 ± 0.1582 |

| M18 | 20.5581 ± 0.0958 | 26.9529 ± 0.0832 | 0.4347 ± 0.1474 | 4.3091 ± 0.1864 |

| M19 | 34.6615 ± 0.2258 | 35.4839 ± 0.2494 | 0.7339 ± 0.1079 | 4.8675 ± 0.0702 |

| M20 | 11.1222 ± 1.2002 | 8.0692 ± 0.6102 | 0.1418 ± 0.0471 | 2.5033 ± 0.1586 |

| M21 | 23.2015 ± 0.0305 | 39.6689 ± 0.0492 | 0.3042 ± 0.0082 | 5.5220 ± 0.0132 |

| M22 | 10.4099 ± 0.4283 | 6.6141 ± 0.3885 | 0.1253 ± 0.0229 | 2.2779 ± 0.1181 |

| M23 | 25.6978 ± 1.5468 | 40.4677 ± 4.9449 | 0.5540 ± 0.1370 | 5.2461 ± 0.1876 |

| M24 | 17.7168 ± 0.4298 | 21.7228 ± 0.0926 | 0.1836 ± 0.0471 | 4.1968 ± 0.1055 |

| M25 | 8.9412 ± 0.4446 | 5.4733 ± 0.4172 | 0.1486 ± 0.0107 | 1.9946 ± 0.0899 |

| M26 | 4.8216 ± 0.2124 | 1.7788 ± 0.1768 | 0.0470 ± 0.0127 | 1.2077 ± 0.0828 |

| M27 | 21.5124 ± 0.0638 | 25.0652 ± 0.0790 | 1.1234 ± 0.0136 | 3.5919 ± 0.0054 |

| M28 | 17.4641 ± 0.0344 | 23.2186 ± 0.0876 | 0.1943 ± 0.0028 | 4.3003 ± 0.0088 |

| M29 | 28.6987 ± 0.8851 | 50.9940 ± 1.9664 | 0.8343 ± 0.3986 | 5.7069 ± 0.3573 |

| M30 | 17.1534 ± 0.0556 | 20.1168 ± 0.1533 | 0.4249 ± 0.0178 | 3.6293 ± 0.0084 |

| M31 | 19.5345 ± 0.8729 | 24.3787 ± 3.2373 | 0.4066 ± 0.1627 | 4.1023 ± 0.2711 |

| M32 | 11.8139 ± 0.5076 | 8.7204 ± 0.5924 | 0.4551 ± 0.0443 | 2.2330 ± 0.0639 |

| M33 | 6.4637 ± 0.4729 | 2.7401 ± 0.5679 | 0.2199 ± 0.0282 | 1.2756 ± 0.1744 |

| M34 | 5.7425 ± 0.1306 | 2.3578 ± 0.0988 | 0.1237 ± 0.0091 | 1.2667 ± 0.0179 |

| M35 | 4.3801 ± 0.1654 | 1.4935 ± 0.1001 | 0.0253 ± 0.0078 | 1.1595 ± 0.0158 |

| M36 | 9.2847 ± 0.4230 | 6.0340 ± 0.7221 | 0.1406 ± 0.0637 | 2.1329 ± 0.2163 |

| M37 | 15.8565 ± 0.0427 | 18.4491 ± 0.0675 | 0.1094 ± 0.0091 | 4.0119 ± 0.0294 |

| M38 | 19.3837 ± 0.0721 | 22.2333 ± 0.2133 | 0.5082 ± 0.0140 | 3.7846 ± 0.0105 |

| M39 | 6.0214 ± 0.4750 | 2.7485 ± 0.3543 | 0.0733 ± 0.0340 | 1.4717 ± 0.0547 |

| M40 | 12.2428 ± 0.5336 | 9.4196 ± 0.9071 | 0.3010 ± 0.0320 | 2.4845 ± 0.1073 |

| M41 | 20.9681 ± 0.0124 | 34.5924 ± 0.0682 | 0.0857 ± 0.0057 | 5.7204 ± 0.0293 |

| M42 | 18.7591 ± 0.0434 | 17.2972 ± 0.0801 | 0.0400 ± 0.0038 | 4.2065 ± 0.0157 |

| M43 | 16.1348 ± 0.1019 | 16.7813 ± 0.2756 | 0.4347 ± 0.0180 | 3.2751 ± 0.0458 |

| M44 | 22.0835 ± 1.2264 | 30.9496 ± 3.5996 | 0.4052 ± 0.0315 | 4.6813 ± 0.2639 |

| M45 | 34.8975 ± 1.6328 | 85.5785 ± 8.9331 | 0.7213 ± 0.0282 | 7.6683 ± 0.4699 |

| M46 | 14.4676 ± 0.3465 | 14.7531 ± 0.9154 | 0.3883 ± 0.0890 | 3.0791 ± 0.2027 |

| M47 | 18.2994 ± 0.0204 | 20.0482 ± 0.4539 | 0.7112 ± 0.0220 | 3.3813 ± 0.0357 |

| M48 | 6.0616 ± 0.2884 | 2.5350 ± 0.3263 | 0.1761 ± 0.0383 | 1.2617 ± 0.1314 |

| M49 | 10.0166 ± 0.3261 | 7.5221 ± 0.4781 | 0.0957 ± 0.0597 | 2.5081 ± 0.1544 |

| M50 | 16.0501 ± 0.6034 | 17.1901 ± 1.2378 | 0.5398 ± 0.1490 | 3.2121 ± 0.1216 |

| M51 | 13.7314 ± 0.4042 | 14.3857 ± 0.7063 | 0.1958 ± 0.0271 | 3.2954 ± 0.1387 |

| M52 | 6.9217 ± 0.3481 | 3.6672 ± 0.3476 | 0.0858 ± 0.0255 | 1.6922 ± 0.0963 |

| M53 | 8.4719 ± 0.0681 | 3.3806 ± 0.0923 | 0.1065 ± 0.0204 | 1.6209 ± 0.0239 |

| M54 | 18.9659 ± 0.0244 | 16.8202 ± 0.0251 | 0.8577 ± 0.0189 | 3.0187 ± 0.0108 |

| M55 | 23.6834 ± 0.0970 | 34.5739 ± 0.1006 | 0.6348 ± 0.0257 | 4.7046 ± 0.0275 |

| M56 | 13.5423 ± 0.5852 | 10.7198 ± 0.7160 | 0.2080 ± 0.0346 | 2.8192 ± 0.0715 |

| M57 | 31.7503 ± 0.0432 | 55.2020 ± 0.1342 | 1.2889 ± 0.0716 | 5.5712 ± 0.0512 |

| M58 | 31.7503 ± 0.0432 | 55.2020 ± 0.1342 | 1.2889 ± 0.0716 | 5.5712 ± 0.0512 |

| M59 | 46.1856 ± 2.9795 | 123.5214 ± 17.0394 | 2.0692 ± 0.1386 | 8.1810 ± 0.5822 |

| M60 | 39.1177 ± 1.6374 | 103.7075 ± 8.0443 | 1.4413 ± 0.3127 | 7.7697 ± 0.3905 |

| M61 | 7.0868 ± 0.5111 | 3.6883 ± 0.6005 | 0.1228 ± 0.0279 | 1.6275 ± 0.1182 |

| M62 | 13.5618 ± 0.0370 | 14.3295 ± 0.0661 | 0.0800 ± 0.0030 | 3.5818 ± 0.0157 |

| M63 | 23.9225 ± 0.0346 | 32.7363 ± 0.0219 | 1.0475 ± 0.0375 | 4.2351 ± 0.0248 |

| M64 | 26.7661 ± 1.9512 | 48.4289 ± 5.0875 | 0.4308 ± 0.1067 | 5.9603 ± 0.2228 |

| M65 | 18.1773 ± 0.1006 | 21.2011 ± 0.0492 | 0.1935 ± 0.0059 | 4.1280 ± 0.0175 |

| M66 | 9.6528 ± 0.7924 | 7.3406 ± 1.2164 | 0.0312 ± 0.0177 | 2.6777 ± 0.1597 |

| M67 | 10.4995 ± 1.0796 | 5.6969 ± 1.4702 | 0.1881 ± 0.0490 | 2.0150 ± 0.3342 |

| M68 | 8.7545 ± 0.7574 | 4.5061 ± 0.5633 | 0.2747 ± 0.0844 | 1.6618 ± 0.0976 |

| M69 | 36.1343 ± 0.6599 | 97.5154 ± 3.8376 | 0.7023 ± 0.1977 | 8.2797 ± 0.4425 |

| M70 | 12.7835 ± 1.2833 | 8.4669 ± 1.2651 | 0.2515 ± 0.0327 | 2.4252 ± 0.1728 |

| M71 | 18.9095 ± 1.0741 | 8.0304 ± 0.5127 | 0.7660 ± 0.0286 | 2.1248 ± 0.0874 |

| M72 | 13.7755 ± 0.0228 | 11.8785 ± 0.0640 | 0.2268 ± 0.0140 | 2.9428 ± 0.0147 |

| M73 | 18.9490 ± 0.1488 | 22.3719 ± 0.1352 | 0.6427 ± 0.0011 | 3.6514 ± 0.0132 |

| M74 | 12.8273 ± 0.8096 | 12.8810 ± 1.5903 | 0.1437 ± 0.0237 | 3.1977 ± 0.1660 |

| M75 | 8.8166 ± 0.4427 | 5.1042 ± 0.6677 | 0.3264 ± 0.0164 | 1.7183 ± 0.1404 |

| M76 | 13.6000 ± 0.4200 | 13.9966 ± 0.8214 | 0.2216 ± 0.0955 | 3.2117 ± 0.1057 |

| M77 | 19.6604 ± 0.0520 | 23.6787 ± 0.1202 | 0.7318 ± 0.0477 | 3.7017 ± 0.0478 |

| M78 | 28.5223 ± 0.7303 | 51.4603 ± 4.2993 | 0.6988 ± 0.2741 | 5.8438 ± 0.3427 |

| M79 | 72.3118 ± 0.0962 | 394.3491 ± 1.1429 | 1.5495 ± 0.1230 | 16.3962 ± 0.1913 |

| M80 | 70.8440 ± 0.0414 | 389.6699 ± 0.6678 | 0.8740 ± 0.2817 | 17.4775 ± 0.6825 |

| M81 | 61.7887 ± 0.0020 | 286.4368 ± 0.2803 | 0.9682 ± 0.1308 | 14.5443 ± 0.2427 |

| M82 | 53.5994 ± 0.1975 | 219.1957 ± 0.4595 | 0.9803 ± 0.0779 | 12.4791 ± 0.1346 |

| M83 | 44.7018 ± 1.8823 | 143.0156 ± 3.9477 | 0.8981 ± 0.5581 | 10.0817 ± 0.6157 |

| M84 | 49.1303 ± 3.6158 | 159.5338 ± 22.9784 | 0.8566 ± 0.2157 | 10.7198 ± 1.1278 |

| M85 | 27.9017 ± 2.4205 | 50.6658 ± 10.9597 | 1.0513 ± 0.1534 | 5.3937 ± 0.7153 |

| M86 | 23.8403 ± 0.4284 | 44.4567 ± 1.4315 | 0.2151 ± 0.0713 | 6.0946 ± 0.3148 |

| Material Code | (mm) | PAR | CO | (kg/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 4.8024 ± 0.0145 | 0.8482 ± 0.0026 | 1.8588 ± 0.0050 | 0.7195 ± 0.0044 | 1488.9464 ± 61.4754 |

| M2 | 4.7681 ± 0.0053 | 0.8569 ± 0.0025 | 2.1883 ± 0.0149 | 0.7343 ± 0.0042 | 1136.3247 ± 17.7141 |

| M3 | 5.3977 ± 0.0157 | 0.9483 ± 0.0029 | 1.1992 ± 0.0043 | 0.8994 ± 0.0055 | 1144.2173 ± 13.9085 |

| M4 | 2.0871 ± 0.1372 | 0.8665 ± 0.0256 | 2.0065 ± 0.3057 | 0.7512 ± 0.0444 | 1037.7582 ± 11.2913 |

| M5 | 4.0447 ± 0.2465 | 0.9907 ± 0.0021 | 1.0609 ± 0.0040 | 0.9815 ± 0.0041 | 1041.5236 ± 21.9337 |

| M6 | 3.4803 ± 0.0862 | 0.8438 ± 0.0044 | 1.4066 ± 0.0695 | 0.7119 ± 0.0074 | 1033.5448 ± 5.0716 |

| M7 | 2.3056 ± 0.2561 | 0.8539 ± 0.0354 | 2.0899 ± 0.3343 | 0.7301 ± 0.0600 | 1046.2543 ± 2.5595 |

| M8 | 2.4829 ± 0.1340 | 0.9417 ± 0.0179 | 1.5397 ± 0.1598 | 0.8870 ± 0.0337 | 1021.5987 ± 2.5211 |

| M9 | 3.0509 ± 0.2158 | 0.8870 ± 0.0149 | 1.1422 ± 0.1043 | 0.7869 ± 0.0263 | 1129.3950 ± 18.6040 |

| M10 | 1.0049 ± 0.0170 | 0.9509 ± 0.0191 | 1.2458 ± 0.0498 | 0.9046 ± 0.0359 | 1129.5459 ± 7.3812 |

| M11 | 2.4666 ± 0.1673 | 0.9893 ± 0.0024 | 1.0822 ± 0.0188 | 0.9787 ± 0.0048 | 1166.3217 ± 29.7223 |

| M12 | 7.1480 ± 0.0082 | 0.5772 ± 0.0073 | 1.8390 ± 0.0242 | 0.3332 ± 0.0084 | 1012.2740 ± 4.4324 |

| M13 | 2.5609 ± 0.0642 | 0.6894 ± 0.0230 | 1.2913 ± 0.0382 | 0.4756 ± 0.0321 | 1064.9640 ± 17.7384 |

| M14 | 2.6216 ± 0.0553 | 0.8735 ± 0.0262 | 1.2913 ± 0.0382 | 0.7634 ± 0.0453 | 1524.1756 ± 74.4743 |

| M15 | 3.1072 ± 0.0505 | 0.9746 ± 0.0042 | 1.1980 ± 0.0171 | 0.9499 ± 0.0081 | 1138.1532 ± 10.8961 |

| M16 | 1.5327 ± 0.0645 | 0.9526 ± 0.0055 | 1.5779 ± 0.0247 | 0.9074 ± 0.0105 | 1054.2142 ± 12.6700 |

| M17 | 3.4276 ± 0.1098 | 0.9584 ± 0.0057 | 1.1899 ± 0.0533 | 0.9186 ± 0.0109 | 1017.0886 ± 11.5041 |

| M18 | 5.8581 ± 0.0090 | 0.8952 ± 0.0055 | 1.4870 ± 0.0078 | 0.8015 ± 0.0099 | 1161.8369 ± 66.8317 |

| M19 | 6.7218 ± 0.0234 | 0.6093 ± 0.0019 | 3.5684 ± 0.0202 | 0.3712 ± 0.0024 | 1022.0965 ± 9.1248 |

| M20 | 3.2038 ± 0.1210 | 0.9096 ± 0.0643 | 1.2922 ± 0.0455 | 0.8301 ± 0.1174 | 1062.3762 ± 30.1516 |

| M21 | 7.1069 ± 0.0044 | 0.9623 ± 0.0010 | 1.0805 ± 0.0038 | 0.9260 ± 0.0019 | 1183.4414 ± 61.6402 |

| M22 | 2.9011 ± 0.0856 | 0.8759 ± 0.0212 | 1.4243 ± 0.1383 | 0.7675 ± 0.0372 | 1069.8080 ± 2.2986 |

| M23 | 7.1692 ± 0.4365 | 0.8768 ± 0.0302 | 1.3694 ± 0.2112 | 0.7693 ± 0.0531 | 1040.5420 ± 1.1631 |

| M24 | 5.2591 ± 0.0112 | 0.9329 ± 0.0233 | 1.0471 ± 0.0061 | 0.8707 ± 0.0431 | 1104.6416 ± 36.4457 |

| M25 | 2.6386 ± 0.0997 | 0.9275 ± 0.0111 | 1.2835 ± 0.0898 | 0.8603 ± 0.0206 | 1220.7252 ± 10.9242 |

| M26 | 1.5037 ± 0.0753 | 0.9796 ± 0.0065 | 1.1337 ± 0.1098 | 0.9596 ± 0.0127 | 1060.4850 ± 8.4638 |

| M27 | 5.6492 ± 0.0089 | 0.8250 ± 0.0012 | 2.1502 ± 0.0188 | 0.6806 ± 0.0021 | 1031.7612 ± 1.1108 |

| M28 | 5.4372 ± 0.0102 | 0.9781 ± 0.0001 | 1.1716 ± 0.0110 | 0.9566 ± 0.0002 | 1137.5533 ± 110.0489 |

| M29 | 8.0568 ± 0.1556 | 0.8822 ± 0.0123 | 1.2159 ± 0.0605 | 0.7784 ± 0.0218 | 1037.6201 ± 1.5074 |

| M30 | 5.0609 ± 0.0193 | 0.9269 ± 0.0008 | 1.7778 ± 0.0017 | 0.8591 ± 0.0016 | 1129.3280 ± 19.0011 |

| M31 | 5.5628 ± 0.3778 | 0.8940 ± 0.0214 | 1.4104 ± 0.1898 | 0.7995 ± 0.0380 | 1093.2696 ± 6.6047 |

| M32 | 3.3308 ± 0.1143 | 0.8860 ± 0.0120 | 2.0814 ± 0.0833 | 0.7851 ± 0.0212 | 1046.4534 ± 2.6339 |

| M33 | 1.8609 ± 0.1973 | 0.9030 ± 0.0310 | 1.9729 ± 0.2588 | 0.8160 ± 0.0556 | 1132.4729 ± 40.3263 |

| M34 | 1.7324 ± 0.0361 | 0.9478 ± 0.0018 | 1.4486 ± 0.0725 | 0.8983 ± 0.0034 | 1079.2448 ± 17.4996 |

| M35 | 1.3784 ± 0.0464 | 0.9888 ± 0.0051 | 1.1031 ± 0.0223 | 0.9777 ± 0.0100 | 1178.5286 ± 14.7084 |

| M36 | 2.7684 ± 0.1687 | 0.9363 ± 0.0159 | 1.3883 ± 0.2093 | 0.8768 ± 0.0296 | 1112.4620 ± 54.8868 |

| M37 | 4.8467 ± 0.0089 | 0.9603 ± 0.0041 | 1.0911 ± 0.0033 | 0.9221 ± 0.0078 | 1463.3158 ± 20.9860 |

| M38 | 5.3205 ± 0.0256 | 0.8623 ± 0.0016 | 1.6615 ± 0.0055 | 0.7436 ± 0.0028 | 1017.0525 ± 6.7683 |

| M39 | 1.8680 ± 0.1213 | 0.9754 ± 0.0140 | 1.1872 ± 0.0801 | 0.9515 ± 0.0273 | 1048.4303 ± 10.8169 |

| M40 | 3.4605 ± 0.1670 | 0.8879 ± 0.0056 | 1.3141 ± 0.0738 | 0.7883 ± 0.0100 | 1107.0333 ± 22.6413 |

| M41 | 6.6366 ± 0.0065 | 0.9943 ± 0.0006 | 1.0692 ± 0.0037 | 0.9887 ± 0.0011 | 1052.3485 ± 3.5083 |

| M42 | 4.6929 ± 0.0109 | 0.7859 ± 0.0033 | 1.0348 ± 0.0056 | 0.6177 ± 0.0052 | 1330.7672 ± 45.1382 |

| M43 | 4.6223 ± 0.0380 | 0.9000 ± 0.0034 | 1.4990 ± 0.0179 | 0.8100 ± 0.0062 | 1165.6529 ± 30.7861 |

| M44 | 6.2706 ± 0.3595 | 0.8920 ± 0.0044 | 1.1790 ± 0.0666 | 0.7957 ± 0.0079 | 1042.8653 ± 4.1377 |

| M45 | 10.4293 ± 0.5376 | 0.9388 ± 0.0111 | 1.3231 ± 0.0525 | 0.8814 ± 0.0208 | 1120.0982 ± 8.4804 |

| M46 | 4.3327 ± 0.1357 | 0.9407 ± 0.0121 | 1.5265 ± 0.0485 | 0.8851 ± 0.0229 | 1141.2930 ± 24.8202 |

| M47 | 5.0521 ± 0.0570 | 0.8673 ± 0.0099 | 2.0416 ± 0.0810 | 0.7523 ± 0.0173 | 1011.0311 ± 3.7372 |

| M48 | 1.7937 ± 0.1137 | 0.9291 ± 0.0193 | 1.6628 ± 0.1245 | 0.8636 ± 0.0358 | 1019.2967 ± 2.3084 |

| M49 | 3.0937 ± 0.0977 | 0.9704 ± 0.0140 | 1.1301 ± 0.0684 | 0.9418 ± 0.0270 | 1086.6164 ± 15.6338 |

| M50 | 4.6763 ± 0.1703 | 0.9153 ± 0.0016 | 1.7412 ± 0.0325 | 0.8379 ± 0.0030 | 1030.9897 ± 6.3122 |

| M51 | 4.2789 ± 0.1044 | 0.9791 ± 0.0056 | 1.1953 ± 0.0898 | 0.9586 ± 0.0109 | 1366.3130 ± 44.7116 |

| M52 | 2.1593 ± 0.1012 | 0.9802 ± 0.0045 | 1.2235 ± 0.0636 | 0.9607 ± 0.0089 | 1109.0903 ± 43.6722 |

| M53 | 2.0746 ± 0.0282 | 0.7694 ± 0.0154 | 1.0419 ± 0.0030 | 0.5921 ± 0.0238 | 4581.6074 ± 0.0000 |

| M54 | 4.6278 ± 0.0034 | 0.7666 ± 0.0014 | 3.4455 ± 0.0119 | 0.5876 ± 0.0021 | 1194.0905 ± 24.6250 |

| M55 | 6.6348 ± 0.0097 | 0.8801 ± 0.0025 | 1.9456 ± 0.0068 | 0.7746 ± 0.0043 | 1045.2902 ± 8.9089 |

| M56 | 3.6930 ± 0.1240 | 0.8571 ± 0.0197 | 2.0282 ± 0.0716 | 0.7349 ± 0.0336 | 1189.6787 ± 50.8046 |

| M57 | 8.3836 ± 0.0102 | 0.8295 ± 0.0009 | 2.8152 ± 0.0489 | 0.6881 ± 0.0015 | 1033.1391 ± 11.2427 |

| M58 | 8.3836 ± 0.0102 | 0.8295 ± 0.0009 | 1.9286 ± 0.0126 | 0.6881 ± 0.0015 | 1157.0886 ± 64.1129 |

| M59 | 12.5206 ± 0.8720 | 0.8515 ± 0.0080 | 2.1520 ± 0.1377 | 0.7251 ± 0.0135 | 1002.8225 ± 1.0972 |

| M60 | 11.4853 ± 0.4455 | 0.9225 ± 0.0120 | 1.6990 ± 0.0956 | 0.8512 ± 0.0221 | 1111.5649 ± 12.9710 |

| M61 | 2.1615 ± 0.1702 | 0.9579 ± 0.0206 | 1.0682 ± 0.0363 | 0.9180 ± 0.0390 | 1180.8279 ± 23.0264 |

| M62 | 4.2714 ± 0.0098 | 0.9895 ± 0.0004 | 1.1056 ± 0.0042 | 0.9791 ± 0.0008 | 1130.7878 ± 20.7664 |

| M63 | 6.4561 ± 0.0022 | 0.8478 ± 0.0011 | 2.2264 ± 0.0058 | 0.7188 ± 0.0019 | 1014.9481 ± 4.2262 |

| M64 | 7.8452 ± 0.4138 | 0.9218 ± 0.0231 | 1.1036 ± 0.1034 | 0.8500 ± 0.0424 | 1145.9640 ± 6.3269 |

| M65 | 5.1956 ± 0.0061 | 0.8980 ± 0.0040 | 1.0799 ± 0.0103 | 0.8064 ± 0.0071 | 1038.4326 ± 3.1035 |

| M66 | 3.0503 ± 0.2511 | 0.9927 ± 0.0005 | 1.0424 ± 0.0451 | 0.9855 ± 0.0010 | 1532.0500 ± 21.4525 |

| M67 | 2.6791 ± 0.3377 | 0.8016 ± 0.0542 | 1.3403 ± 0.2893 | 0.6445 ± 0.0853 | 1072.9821 ± 5.2822 |

| M68 | 2.3921 ± 0.1514 | 0.8597 ± 0.0222 | 1.7901 ± 0.1798 | 0.7393 ± 0.0385 | 1058.8986 ± 5.6775 |

| M69 | 11.1413 ± 0.2187 | 0.9686 ± 0.0024 | 1.2586 ± 0.0854 | 0.9383 ± 0.0047 | 1087.2473 ± 23.9530 |

| M70 | 3.2774 ± 0.2416 | 0.8071 ± 0.0327 | 1.9780 ± 0.2127 | 0.6521 ± 0.0534 | 1066.5897 ± 21.4609 |

| M71 | 3.1965 ± 0.1029 | 0.5317 ± 0.0200 | 2.2348 ± 0.1230 | 0.2830 ± 0.0212 | 1088.8187 ± 14.9108 |

| M72 | 3.8890 ± 0.0105 | 0.8869 ± 0.0037 | 1.7310 ± 0.0011 | 0.7866 ± 0.0067 | 1124.4841 ± 38.0876 |

| M73 | 5.3371 ± 0.0161 | 0.8849 ± 0.0060 | 1.9927 ± 0.0092 | 0.7830 ± 0.0106 | 1148.9095 ± 40.5477 |

| M74 | 4.0447 ± 0.2465 | 0.9907 ± 0.0021 | 1.0733 ± 0.0717 | 0.9815 ± 0.0041 | 1182.5738 ± 29.0432 |

| M75 | 2.5455 ± 0.1702 | 0.9065 ± 0.0159 | 1.7437 ± 0.1140 | 0.8219 ± 0.0286 | 1042.5689 ± 5.0350 |

| M76 | 4.2203 ± 0.1241 | 0.9749 ± 0.0095 | 1.1380 ± 0.0425 | 0.9506 ± 0.0186 | 1077.4804 ± 26.4760 |

| M77 | 5.4908 ± 0.0139 | 0.8774 ± 0.0022 | 2.0912 ± 0.0240 | 0.7698 ± 0.0038 | 1041.4385 ± 3.5975 |

| M78 | 8.0899 ± 0.3367 | 0.8908 ± 0.0155 | 1.2864 ± 0.2005 | 0.7937 ± 0.0278 | 1017.0338 ± 6.8907 |

| M79 | 22.4076 ± 0.0325 | 0.9735 ± 0.0001 | 1.4088 ± 0.0042 | 0.9477 ± 0.0002 | 1052.3626 ± 1.5528 |

| M80 | 22.2743 ± 0.0191 | 0.9878 ± 0.0004 | 1.0482 ± 0.0022 | 0.9757 ± 0.0007 | 1103.2307 ± 11.0995 |

| M81 | 19.0972 ± 0.0094 | 0.9710 ± 0.0005 | 1.2937 ± 0.0028 | 0.9428 ± 0.0009 | 1102.4670 ± 4.1408 |

| M82 | 16.7060 ± 0.0175 | 0.9792 ± 0.0027 | 1.2833 ± 0.0027 | 0.9588 ± 0.0053 | 1119.3345 ± 16.6831 |

| M83 | 13.4933 ± 0.1859 | 0.9490 ± 0.0266 | 1.3891 ± 0.2819 | 0.9012 ± 0.0503 | 1057.9408 ± 6.5932 |

| M84 | 14.2284 ± 1.0086 | 0.9100 ± 0.0141 | 1.2794 ± 0.3034 | 0.8283 ± 0.0257 | 1061.2280 ± 6.2406 |

| M85 | 8.0017 ± 0.8507 | 0.9001 ± 0.0213 | 1.8439 ± 0.1110 | 0.8104 ± 0.0384 | 1014.5767 ± 0.0575 |

| M86 | 7.5229 ± 0.1211 | 0.9914 ± 0.0019 | 1.0813 ± 0.0387 | 0.9828 ± 0.0037 | 1332.0378 ± 47.4495 |

| Statistics | (mm) | (mm2) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | PAR | CO | (kg/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of data | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 |

| Mean | 19.5652 | 38.7125 | 5.5796 | 4.1264 | 0.4487 | 0.8986 | 1.5286 | 0.8152 | 1155.9725 |

| Standard deviation | 14.2357 | 71.7070 | 4.2819 | 3.1853 | 0.4283 | 0.0879 | 0.4970 | 0.1437 | 390.0189 |

| Coefficient of variation (CV) | 0.7276 | 1.8523 | 0.7674 | 0.7719 | 0.9546 | 0.0978 | 0.3251 | 0.1762 | 0.3374 |

| Standard error of mean | 1.5351 | 7.7324 | 0.4617 | 0.3435 | 0.0462 | 0.0095 | 0.0536 | 0.0155 | 42.0568 |

| Upper 95% CL of mean | 22.6173 | 54.0865 | 6.4976 | 4.8093 | 0.5405 | 0.9174 | 1.6352 | 0.8460 | 1239.5928 |

| Lower 95% CL of mean | 16.5130 | 23.3385 | 4.6615 | 3.4435 | 0.3569 | 0.8797 | 1.4221 | 0.7844 | 1072.3523 |

| Geometric mean | 15.7651 | 15.8095 | 4.4835 | 3.3309 | 0.2833 | 0.8936 | 1.4644 | 0.7986 | 1129.1905 |

| Skewness | 1.7990 | 3.5898 | 2.1407 | 2.2916 | 1.5069 | −1.9357 | 1.7530 | −1.4425 | 8.0424 |

| Kurtosis | 6.3773 | 16.4157 | 7.9818 | 8.8273 | 5.1018 | 7.9619 | 7.0694 | 5.8125 | 70.8776 |

| Maximum | 72.3118 | 394.3491 | 22.4076 | 17.4775 | 2.0692 | 0.9943 | 3.5684 | 0.9887 | 4581.6074 |

| Upper quartile | 23.6834 | 34.5924 | 6.6366 | 4.7046 | 0.7023 | 0.9623 | 1.8390 | 0.9260 | 1144.2173 |

| Median | 16.0925 | 16.8008 | 4.6251 | 3.2575 | 0.2653 | 0.9081 | 1.3549 | 0.8251 | 1088.0330 |

| Lower quartile | 10.0150 | 6.0340 | 2.7684 | 2.1248 | 0.1323 | 0.8665 | 1.1716 | 0.7512 | 1042.5689 |

| Minimum | 3.3205 | 0.7933 | 1.0049 | 0.7749 | 0.0253 | 0.5317 | 1.0348 | 0.2830 | 1002.8225 |

| Range | 68.9913 | 393.5558 | 21.4027 | 16.7026 | 2.0439 | 0.4626 | 2.5336 | 0.7057 | 3578.7849 |

| 13.6684 | 28.5584 | 3.8682 | 2.5798 | 0.5700 | 0.0958 | 0.6674 | 0.1748 | 101.6484 |

Appendix D. Comprehensive Apparent Specific Gravity Comparison Database for Model Validation

| Code | Values | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | % | m | °C | mm | - | cm/s | Equation (22) | Equation (24) | Equation (25) | Equation (27) | Equation (29) | Equation (31) | Equation (83) | |

| M1 | 26.5 | 58.0 | 72 | 26.5 | 3.7212 | 0.0388 | 23.1685 ± 1.7875 | 1.5681 ± 0.0837 | 2.2972 ± 0.1909 | 1.3369 ± 0.0361 | 2.3391 ± 0.2032 | 2.3281 ± 0.1852 | 2.2503 ± 0.1847 | 1.4294 ± 0.0483 |

| M2 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 3.2398 | 0.0337 | 9.1586 ± 0.7645 | 1.1203 ± 0.0175 | 1.2693 ± 0.0400 | 1.1196 ± 0.0137 | 1.2573 ± 0.0397 | 1.2960 ± 0.0436 | 1.2567 ± 0.0384 | 1.1466 ± 0.0159 |

| M3 | 26.5 | 58.0 | 72 | 26.5 | 4.1031 | 0.0427 | 11.8296 ± 0.6946 | 1.1433 ± 0.0158 | 1.3259 ± 0.0363 | 1.1137 ± 0.0093 | 1.3241 ± 0.0375 | 1.3501 ± 0.0376 | 1.3126 ± 0.0350 | 1.1502 ± 0.0117 |

| M4 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 1.4459 | 0.0151 | 1.8790 ± 0.3611 | 1.0306 ± 0.0082 | 1.0541 ± 0.0159 | 1.0447 ± 0.0121 | 1.0476 ± 0.0138 | 1.0442 ± 0.0157 | 1.0493 ± 0.0147 | 1.0512 ± 0.0125 |

| M5 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 4.5029 | 0.0469 | 5.7112 ± 1.8344 | 1.0364 ± 0.0206 | 1.0812 ± 0.0472 | 1.0379 ± 0.0169 | 1.0773 ± 0.0466 | 1.0891 ± 0.0516 | 1.0773 ± 0.0453 | 1.0545 ± 0.0221 |

| M6 | 27.0 | 61.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.6842 | 0.0280 | 3.3059 ± 0.3041 | 1.0271 ± 0.0040 | 1.0556 ± 0.0087 | 1.0372 ± 0.0048 | 1.0494 ± 0.0079 | 1.0579 ± 0.0097 | 1.0520 ± 0.0082 | 1.0489 ± 0.0057 |

| M7 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 1.5798 | 0.0165 | 2.3521 ± 0.0856 | 1.0363 ± 0.0019 | 1.0666 ± 0.0037 | 1.0534 ± 0.0027 | 1.0584 ± 0.0033 | 1.0588 ± 0.0038 | 1.0611 ± 0.0035 | 1.0610 ± 0.0028 |

| M8 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 1.7304 | 0.0180 | 1.5937 ± 0.1138 | 1.0183 ± 0.0018 | 1.0322 ± 0.0034 | 1.0269 ± 0.0027 | 1.0283 ± 0.0030 | 1.0262 ± 0.0033 | 1.0294 ± 0.0032 | 1.0335 ± 0.0030 |

| M9 | 27.0 | 61.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.5364 | 0.0264 | 7.3131 ± 0.6676 | 1.1083 ± 0.0170 | 1.2372 ± 0.0386 | 1.1228 ± 0.0156 | 1.2203 ± 0.0372 | 1.2604 ± 0.0429 | 1.2248 ± 0.0369 | 1.1448 ± 0.0173 |

| M10 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 0.7749 | 0.0081 | 2.1555 ± 0.0871 | 1.1045 ± 0.0055 | 1.1723 ± 0.0099 | 1.1453 ± 0.0082 | 1.1542 ± 0.0086 | 1.1174 ± 0.0087 | 1.1552 ± 0.0091 | 1.1336 ± 0.0071 |

| M11 | 27.0 | 61.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.0615 | 0.0215 | 7.0939 ± 0.8232 | 1.1351 ± 0.0260 | 1.2908 ± 0.0586 | 1.1631 ± 0.0263 | 1.2659 ± 0.0555 | 1.3163 ± 0.0657 | 1.2746 ± 0.0559 | 1.1812 ± 0.0279 |

| M12 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 4.6762 | 0.0487 | 3.0720 ± 0.5859 | 1.0114 ± 0.0036 | 1.0245 ± 0.0081 | 1.0145 ± 0.0038 | 1.0224 ± 0.0076 | 1.0266 ± 0.0090 | 1.0231 ± 0.0077 | 1.0235 ± 0.0055 |

| M13 | 27.0 | 61.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.0425 | 0.0213 | 3.8223 ± 0.6851 | 1.0507 ± 0.0138 | 1.1027 ± 0.0298 | 1.0701 ± 0.0172 | 1.0910 ± 0.0269 | 1.1055 ± 0.0331 | 1.0959 ± 0.0282 | 1.0823 ± 0.0186 |

| M14 | 27.0 | 61.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.0551 | 0.0214 | 14.7778 ± 1.3472 | 1.4845 ± 0.0782 | 2.0887 ± 0.1795 | 1.4555 ± 0.0576 | 2.0475 ± 0.1794 | 2.1939 ± 0.1943 | 2.0388 ± 0.1724 | 1.5085 ± 0.0686 |

| M15 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.5080 | 0.0261 | 7.5561 ± 0.3814 | 1.1159 ± 0.0100 | 1.2542 ± 0.0227 | 1.1307 ± 0.0092 | 1.2363 ± 0.0220 | 1.2792 ± 0.0253 | 1.2410 ± 0.0217 | 1.1532 ± 0.0101 |

| M16 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 1.1202 | 0.0117 | 1.8021 ± 0.2879 | 1.0440 ± 0.0093 | 1.0747 ± 0.0173 | 1.0629 ± 0.0140 | 1.0663 ± 0.0150 | 1.0552 ± 0.0158 | 1.0676 ± 0.0159 | 1.0665 ± 0.0134 |

| M17 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.7075 | 0.0282 | 2.1848 ± 0.8575 | 1.0148 ± 0.0085 | 1.0292 ± 0.0181 | 1.0212 ± 0.0114 | 1.0258 ± 0.0161 | 1.0290 ± 0.0197 | 1.0271 ± 0.0170 | 1.0293 ± 0.0142 |

| M18 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 4.3092 | 0.0449 | 12.9220 ± 3.2682 | 1.1660 ± 0.0791 | 1.3782 ± 0.1814 | 1.1228 ± 0.0433 | 1.3801 ± 0.1889 | 1.4013 ± 0.1850 | 1.3632 ± 0.1751 | 1.1624 ± 0.0547 |

| M19 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 5.1158 | 0.0533 | 4.5621 ± 1.1056 | 1.0202 ± 0.0081 | 1.0450 ± 0.0186 | 1.0219 ± 0.0072 | 1.0425 ± 0.0182 | 1.0494 ± 0.0205 | 1.0428 ± 0.0178 | 1.0347 ± 0.0103 |

| M20 | 26.9 | 62.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.5033 | 0.0261 | 4.4827 ± 1.3582 | 1.0503 ± 0.0250 | 1.1061 ± 0.0558 | 1.0644 ± 0.0273 | 1.0959 ± 0.0520 | 1.1135 ± 0.0625 | 1.0998 ± 0.0530 | 1.0791 ± 0.0307 |

| M21 | 27.0 | 61.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 5.5220 | 0.0575 | 17.2645 ± 3.7085 | 1.2157 ± 0.0820 | 1.4923 ± 0.1870 | 1.1209 ± 0.0348 | 1.5124 ± 0.1996 | 1.4960 ± 0.1800 | 1.4749 ± 0.1810 | 1.1732 ± 0.0478 |

| M22 | 26.8 | 64.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.2779 | 0.0237 | 4.4734 ± 0.0951 | 1.0551 ± 0.0019 | 1.1146 ± 0.0041 | 1.0732 ± 0.0022 | 1.1025 ± 0.0038 | 1.1212 ± 0.0046 | 1.1075 ± 0.0039 | 1.0875 ± 0.0024 |

| M23 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 5.2461 | 0.0546 | 6.5470 ± 0.1098 | 1.0367 ± 0.0011 | 1.0826 ± 0.0026 | 1.0354 ± 0.0008 | 1.0797 ± 0.0026 | 1.0904 ± 0.0027 | 1.0788 ± 0.0025 | 1.0535 ± 0.0011 |

| M24 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 4.1968 | 0.0437 | 9.6972 ± 2.0674 | 1.0995 ± 0.0394 | 1.2254 ± 0.0904 | 1.0857 ± 0.0255 | 1.2214 ± 0.0923 | 1.2443 ± 0.0953 | 1.2158 ± 0.0870 | 1.1147 ± 0.0319 |

| M25 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 1.9946 | 0.0208 | 8.1507 ± 0.2604 | 1.1797 ± 0.0097 | 1.3885 ± 0.0220 | 1.2135 ± 0.0095 | 1.3563 ± 0.0210 | 1.4239 ± 0.0247 | 1.3672 ± 0.0210 | 1.2307 ± 0.0101 |

| M26 | 26.8 | 63.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 1.2077 | 0.0126 | 2.1172 ± 0.2030 | 1.0481 ± 0.0062 | 1.0840 ± 0.0118 | 1.0698 ± 0.0093 | 1.0741 ± 0.0103 | 1.0670 ± 0.0114 | 1.0765 ± 0.0109 | 1.0742 ± 0.0090 |

| M27 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 3.5918 | 0.0374 | 4.0441 ± 0.0855 | 1.0257 ± 0.0009 | 1.0550 ± 0.0020 | 1.0327 ± 0.0010 | 1.0500 ± 0.0019 | 1.0595 ± 0.0023 | 1.0518 ± 0.0019 | 1.0455 ± 0.0012 |

| M28 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 4.3003 | 0.0448 | 11.0528 ± 6.0195 | 1.1406 ± 0.1235 | 1.3197 ± 0.2831 | 1.1051 ± 0.0748 | 1.3210 ± 0.2915 | 1.3386 ± 0.2936 | 1.3070 ± 0.2729 | 1.1388 ± 0.0942 |

| M29 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 5.7070 | 0.0594 | 6.7192 ± 0.1578 | 1.0348 ± 0.0015 | 1.0786 ± 0.0034 | 1.0322 ± 0.0010 | 1.0765 ± 0.0035 | 1.0858 ± 0.0037 | 1.0751 ± 0.0033 | 1.0502 ± 0.0015 |

| M30 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 3.6293 | 0.0378 | 10.0052 ± 0.9278 | 1.1216 ± 0.0200 | 1.2748 ± 0.0460 | 1.1085 ± 0.0138 | 1.2679 ± 0.0465 | 1.2995 ± 0.0491 | 1.2628 ± 0.0442 | 1.1398 ± 0.0168 |

| M31 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 4.1023 | 0.0427 | 8.8659 ± 0.3927 | 1.0851 ± 0.0068 | 1.1921 ± 0.0156 | 1.0788 ± 0.0048 | 1.1863 ± 0.0157 | 1.2100 ± 0.0167 | 1.1835 ± 0.0150 | 1.1051 ± 0.0060 |

| M32 | 26.4 | 51.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 2.2330 | 0.0233 | 3.3597 ± 0.1221 | 1.0363 ± 0.0020 | 1.0730 ± 0.0044 | 1.0511 ± 0.0026 | 1.0645 ± 0.0039 | 1.0742 ± 0.0048 | 1.0680 ± 0.0041 | 1.0626 ± 0.0029 |

| M33 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 1.2756 | 0.0133 | 3.6703 ± 0.7912 | 1.1003 ± 0.0300 | 1.1892 ± 0.0612 | 1.1452 ± 0.0424 | 1.1658 ± 0.0535 | 1.1753 ± 0.0641 | 1.1744 ± 0.0571 | 1.1448 ± 0.0398 |

| M34 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 1.2667 | 0.0132 | 2.5736 ± 0.4000 | 1.0610 ± 0.0127 | 1.1093 ± 0.0249 | 1.0890 ± 0.0189 | 1.0960 ± 0.0216 | 1.0920 ± 0.0246 | 1.0999 ± 0.0231 | 1.0918 ± 0.0179 |

| M35 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 1.1595 | 0.0121 | 4.1003 ± 0.2302 | 1.1350 ± 0.0111 | 1.2541 ± 0.0228 | 1.1954 ± 0.0154 | 1.2225 ± 0.0200 | 1.2350 ± 0.0241 | 1.2342 ± 0.0213 | 1.1883 ± 0.0142 |

| M36 | 26.5 | 58.0 | 72 | 26.5 | 2.1329 | 0.0222 | 5.5556 ± 1.9245 | 1.0902 ± 0.0449 | 1.1915 ± 0.0996 | 1.1129 ± 0.0509 | 1.1737 ± 0.0921 | 1.2059 ± 0.1115 | 1.1803 ± 0.0945 | 1.1284 ± 0.0545 |

| M37 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 4.0119 | 0.0418 | 23.6190 ± 0.6599 | 1.5430 ± 0.0288 | 2.2398 ± 0.0657 | 1.3134 ± 0.0121 | 2.2841 ± 0.0701 | 2.2620 ± 0.0633 | 2.1954 ± 0.0636 | 1.4027 ± 0.0162 |

| M38 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 3.7846 | 0.0394 | 3.0224 ± 0.6933 | 1.0149 ± 0.0053 | 1.0313 ± 0.0117 | 1.0196 ± 0.0061 | 1.0283 ± 0.0109 | 1.0335 ± 0.0131 | 1.0295 ± 0.0111 | 1.0294 ± 0.0083 |

| M39 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 1.4717 | 0.0153 | 2.1695 ± 0.3270 | 1.0378 ± 0.0078 | 1.0675 ± 0.0153 | 1.0554 ± 0.0116 | 1.0593 ± 0.0133 | 1.0565 ± 0.0153 | 1.0616 ± 0.0142 | 1.0613 ± 0.0116 |

| M40 | 26.8 | 64.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.4845 | 0.0259 | 6.3492 ± 0.8798 | 1.0879 ± 0.0197 | 1.1903 ± 0.0446 | 1.1044 ± 0.0197 | 1.1749 ± 0.0423 | 1.2078 ± 0.0499 | 1.1800 ± 0.0425 | 1.1238 ± 0.0219 |

| M41 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 5.7204 | 0.0596 | 8.1905 ± 0.3299 | 1.0499 ± 0.0037 | 1.1134 ± 0.0086 | 1.0424 ± 0.0024 | 1.1119 ± 0.0088 | 1.1225 ± 0.0090 | 1.1086 ± 0.0083 | 1.0644 ± 0.0033 |

| M42 | 26.5 | 58.0 | 72 | 26.5 | 4.2066 | 0.0438 | 20.0932 ± 1.6803 | 1.3789 ± 0.0604 | 1.8652 ± 0.1379 | 1.2281 ± 0.0264 | 1.8921 ± 0.1467 | 1.8875 ± 0.1341 | 1.8338 ± 0.1335 | 1.2978 ± 0.0347 |

| M43 | 26.5 | 58.0 | 72 | 26.5 | 3.2751 | 0.0341 | 10.6483 ± 1.2284 | 1.1544 ± 0.0327 | 1.3485 ± 0.0750 | 1.1399 ± 0.0225 | 1.3386 ± 0.0758 | 1.3805 ± 0.0801 | 1.3331 ± 0.0721 | 1.1732 ± 0.0267 |

| M44 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 4.6813 | 0.0488 | 6.2068 ± 0.3610 | 1.0381 ± 0.0040 | 1.0854 ± 0.0091 | 1.0387 ± 0.0031 | 1.0816 ± 0.0090 | 1.0938 ± 0.0099 | 1.0814 ± 0.0087 | 1.0567 ± 0.0042 |

| M45 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 7.6683 | 0.0799 | 17.0037 ± 0.7229 | 1.1441 ± 0.0118 | 1.3285 ± 0.0267 | 1.0734 ± 0.0043 | 1.3458 ± 0.0289 | 1.3234 ± 0.0247 | 1.3173 ± 0.0259 | 1.1173 ± 0.0064 |

| M46 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 3.0791 | 0.0321 | 9.1254 ± 1.0229 | 1.1260 ± 0.0246 | 1.2821 ± 0.0564 | 1.1247 ± 0.0192 | 1.2697 ± 0.0559 | 1.3099 ± 0.0615 | 1.2689 ± 0.0541 | 1.1528 ± 0.0223 |

| M47 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 3.3813 | 0.0352 | 2.0923 ± 0.3825 | 1.0098 ± 0.0027 | 1.0195 ± 0.0058 | 1.0142 ± 0.0036 | 1.0172 ± 0.0052 | 1.0196 ± 0.0064 | 1.0182 ± 0.0055 | 1.0214 ± 0.0048 |

| M48 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 1.2617 | 0.0131 | 1.0109 ± 0.0775 | 1.0175 ± 0.0017 | 1.0279 ± 0.0029 | 1.0238 ± 0.0025 | 1.0253 ± 0.0025 | 1.0168 ± 0.0023 | 1.0250 ± 0.0026 | 1.0282 ± 0.0027 |

| M49 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 2.5081 | 0.0261 | 5.4421 ± 0.6224 | 1.0685 ± 0.0131 | 1.1457 ± 0.0295 | 1.0865 ± 0.0139 | 1.1321 ± 0.0277 | 1.1571 ± 0.0331 | 1.1372 ± 0.0281 | 1.1024 ± 0.0152 |

| M50 | 26.4 | 51.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 3.2121 | 0.0335 | 3.6973 ± 0.4637 | 1.0255 ± 0.0051 | 1.0538 ± 0.0114 | 1.0333 ± 0.0057 | 1.0485 ± 0.0106 | 1.0576 ± 0.0128 | 1.0506 ± 0.0108 | 1.0457 ± 0.0071 |

| M51 | 26.4 | 51.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 3.2954 | 0.0343 | 17.5538 ± 1.3520 | 1.3844 ± 0.0542 | 1.8764 ± 0.1243 | 1.2780 ± 0.0295 | 1.8818 ± 0.1293 | 1.9301 ± 0.1269 | 1.8419 ± 0.1199 | 1.3402 ± 0.0365 |

| M52 | 26.9 | 63.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 1.6921 | 0.0176 | 4.4124 ± 1.2157 | 1.0844 ± 0.0339 | 1.1707 ± 0.0731 | 1.1160 ± 0.0430 | 1.1513 ± 0.0658 | 1.1748 ± 0.0807 | 1.1593 ± 0.0690 | 1.1261 ± 0.0438 |

| M53 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 1.6209 | 0.0169 | 40.0000 ± 0.0000 | 5.0022 ± 0.0000 | 10.1318 ± 0.0000 | 3.7266 ± 0.0000 | 10.2374 ± 0.0000 | 10.6312 ± 0.0000 | 9.7789 ± 0.0000 | 6.4772 ± 0.0000 |

| M54 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 3.0187 | 0.0314 | 11.0197 ± 0.8688 | 1.1799 ± 0.0260 | 1.4056 ± 0.0597 | 1.1654 ± 0.0182 | 1.3929 ± 0.0601 | 1.4437 ± 0.0640 | 1.3875 ± 0.0574 | 1.2000 ± 0.0213 |

| M55 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 4.7046 | 0.0490 | 6.3706 ± 0.7464 | 1.0401 ± 0.0086 | 1.0898 ± 0.0196 | 1.0404 ± 0.0066 | 1.0860 ± 0.0196 | 1.0987 ± 0.0213 | 1.0856 ± 0.0189 | 1.0588 ± 0.0088 |

| M56 | 26.8 | 64.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.8191 | 0.0294 | 10.1905 ± 1.7222 | 1.1717 ± 0.0518 | 1.3850 ± 0.1187 | 1.1658 ± 0.0390 | 1.3695 ± 0.1184 | 1.4224 ± 0.1287 | 1.3672 ± 0.1140 | 1.1974 ± 0.0447 |

| M57 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 5.5712 | 0.0580 | 6.1194 ± 1.2701 | 1.0308 ± 0.0109 | 1.0693 ± 0.0249 | 1.0292 ± 0.0082 | 1.0672 ± 0.0250 | 1.0757 ± 0.0269 | 1.0663 ± 0.0240 | 1.0458 ± 0.0117 |

| M58 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 3.3099 | 0.0345 | 10.2517 ± 2.7803 | 1.1470 ± 0.0660 | 1.3317 ± 0.1514 | 1.1324 ± 0.0480 | 1.3227 ± 0.1519 | 1.3614 ± 0.1630 | 1.3171 ± 0.1455 | 1.1645 ± 0.0568 |

| M59 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 8.1810 | 0.0852 | 2.4884 ± 0.3407 | 1.0039 ± 0.0009 | 1.0085 ± 0.0020 | 1.0048 ± 0.0009 | 1.0079 ± 0.0019 | 1.0093 ± 0.0022 | 1.0081 ± 0.0019 | 1.0099 ± 0.0016 |

| M60 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 7.7696 | 0.0809 | 16.4160 ± 1.1444 | 1.1330 ± 0.0180 | 1.3032 ± 0.0409 | 1.0686 ± 0.0066 | 1.3189 ± 0.0442 | 1.2992 ± 0.0379 | 1.2929 ± 0.0397 | 1.1105 ± 0.0100 |

| M61 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 1.6274 | 0.0170 | 5.8365 ± 0.5003 | 1.1390 ± 0.0185 | 1.2853 ± 0.0404 | 1.1872 ± 0.0222 | 1.2538 ± 0.0368 | 1.2975 ± 0.0451 | 1.2669 ± 0.0382 | 1.1937 ± 0.0219 |

| M62 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 3.5818 | 0.0373 | 9.9609 ± 1.0022 | 1.1226 ± 0.0218 | 1.2769 ± 0.0501 | 1.1101 ± 0.0152 | 1.2696 ± 0.0506 | 1.3020 ± 0.0536 | 1.2648 ± 0.0482 | 1.1413 ± 0.0184 |

| M63 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 4.2351 | 0.0441 | 3.0626 ± 0.4733 | 1.0130 ± 0.0034 | 1.0276 ± 0.0076 | 1.0170 ± 0.0037 | 1.0250 ± 0.0071 | 1.0298 ± 0.0085 | 1.0260 ± 0.0072 | 1.0264 ± 0.0051 |

| M64 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 5.9603 | 0.0621 | 15.7993 ± 0.4152 | 1.1639 ± 0.0082 | 1.3743 ± 0.0188 | 1.0981 ± 0.0036 | 1.3871 ± 0.0200 | 1.3822 ± 0.0182 | 1.3609 ± 0.0182 | 1.1426 ± 0.0049 |

| M65 | 26.5 | 58.0 | 72 | 26.5 | 4.1280 | 0.0430 | 5.3030 ± 0.2624 | 1.0335 ± 0.0028 | 1.0740 ± 0.0065 | 1.0370 ± 0.0025 | 1.0694 ± 0.0063 | 1.0814 ± 0.0072 | 1.0703 ± 0.0062 | 1.0533 ± 0.0033 |

| M66 | 26.5 | 58.0 | 72 | 26.5 | 2.6777 | 0.0279 | 18.6836 ± 0.4722 | 1.5444 ± 0.0255 | 2.2390 ± 0.0585 | 1.4186 ± 0.0147 | 2.2343 ± 0.0605 | 2.3288 ± 0.0606 | 2.1887 ± 0.0564 | 1.4942 ± 0.0186 |

| M67 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 2.0150 | 0.0210 | 3.9620 ± 0.1878 | 1.0557 ± 0.0041 | 1.1121 ± 0.0089 | 1.0779 ± 0.0052 | 1.0990 ± 0.0080 | 1.1142 ± 0.0098 | 1.1045 ± 0.0084 | 1.0890 ± 0.0054 |

| M68 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 1.6618 | 0.0173 | 2.8606 ± 0.1836 | 1.0452 ± 0.0042 | 1.0854 ± 0.0087 | 1.0660 ± 0.0059 | 1.0748 ± 0.0076 | 1.0794 ± 0.0092 | 1.0787 ± 0.0081 | 1.0741 ± 0.0060 |

| M69 | 25.0 | 53.0 | 72 | 25.0 | 8.2797 | 0.0862 | 14.8988 ± 2.3878 | 1.1042 ± 0.0331 | 1.2375 ± 0.0752 | 1.0538 ± 0.0120 | 1.2499 ± 0.0814 | 1.2341 ± 0.0694 | 1.2295 ± 0.0729 | 1.0905 ± 0.0188 |

| M70 | 26.8 | 63.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.4252 | 0.0253 | 4.5699 ± 0.9701 | 1.0532 ± 0.0173 | 1.1119 ± 0.0385 | 1.0689 ± 0.0198 | 1.1008 ± 0.0355 | 1.1195 ± 0.0431 | 1.1052 ± 0.0365 | 1.0838 ± 0.0222 |

| M71 | 26.8 | 64.0 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.1248 | 0.0221 | 4.8730 ± 0.5352 | 1.0699 ± 0.0121 | 1.1458 ± 0.0268 | 1.0921 ± 0.0140 | 1.1307 ± 0.0247 | 1.1546 ± 0.0301 | 1.1369 ± 0.0255 | 1.1066 ± 0.0150 |

| M72 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 2.9428 | 0.0307 | 8.1024 ± 1.5779 | 1.1089 ± 0.0366 | 1.2422 ± 0.0838 | 1.1129 ± 0.0303 | 1.2294 ± 0.0824 | 1.2663 ± 0.0920 | 1.2305 ± 0.0803 | 1.1382 ± 0.0349 |

| M73 | 24.8 | 44.5 | 72 | 23.8 | 3.6514 | 0.0380 | 10.6793 ± 1.8385 | 1.1392 ± 0.0429 | 1.3147 ± 0.0985 | 1.1233 ± 0.0293 | 1.3072 ± 0.0998 | 1.3426 ± 0.1049 | 1.3010 ± 0.0947 | 1.1553 ± 0.0350 |

| M74 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 3.1976 | 0.0333 | 11.0787 ± 1.0934 | 1.1705 ± 0.0310 | 1.3849 ± 0.0711 | 1.1538 ± 0.0212 | 1.3742 ± 0.0720 | 1.4202 ± 0.0760 | 1.3679 ± 0.0684 | 1.1883 ± 0.0250 |

| M75 | 27.0 | 31.5 | 72 | 27.0 | 1.7183 | 0.0179 | 2.4558 ± 0.1892 | 1.0336 ± 0.0037 | 1.0628 ± 0.0075 | 1.0493 ± 0.0053 | 1.0550 ± 0.0066 | 1.0575 ± 0.0079 | 1.0579 ± 0.0070 | 1.0578 ± 0.0056 |

| M76 | 26.4 | 52.0 | 72 | 26.3 | 3.2118 | 0.0335 | 6.4532 ± 1.4484 | 1.0662 ± 0.0239 | 1.1460 ± 0.0545 | 1.0726 ± 0.0219 | 1.1369 ± 0.0527 | 1.1604 ± 0.0605 | 1.1387 ± 0.0521 | 1.0930 ± 0.0260 |

| M77 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 3.7016 | 0.0386 | 4.9009 ± 0.2614 | 1.0341 ± 0.0031 | 1.0742 ± 0.0070 | 1.0406 ± 0.0030 | 1.0685 ± 0.0067 | 1.0813 ± 0.0078 | 1.0703 ± 0.0067 | 1.0559 ± 0.0038 |

| M78 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 5.8438 | 0.0609 | 4.2805 ± 0.9586 | 1.0155 ± 0.0062 | 1.0344 ± 0.0142 | 1.0168 ± 0.0053 | 1.0325 ± 0.0140 | 1.0378 ± 0.0156 | 1.0327 ± 0.0136 | 1.0280 ± 0.0079 |

| M79 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 16.3962 | 0.1708 | 17.8290 ± 0.3091 | 1.0713 ± 0.0024 | 1.1611 ± 0.0055 | 1.0242 ± 0.0006 | 1.1757 ± 0.0061 | 1.1424 ± 0.0045 | 1.1562 ± 0.0053 | 1.0570 ± 0.0012 |

| M80 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 17.4775 | 0.1821 | 27.5594 ± 1.7528 | 1.1583 ± 0.0195 | 1.3552 ± 0.0436 | 1.0392 ± 0.0033 | 1.3935 ± 0.0489 | 1.2905 ± 0.0328 | 1.3451 ± 0.0424 | 1.0936 ± 0.0076 |

| M81 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 14.5443 | 0.1515 | 24.3333 ± 0.5774 | 1.1490 ± 0.0070 | 1.3357 ± 0.0157 | 1.0442 ± 0.0014 | 1.3684 ± 0.0175 | 1.2882 ± 0.0124 | 1.3258 ± 0.0153 | 1.0947 ± 0.0029 |

| M82 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 12.4791 | 0.1300 | 23.9607 ± 1.9597 | 1.1698 ± 0.0276 | 1.3835 ± 0.0618 | 1.0551 ± 0.0061 | 1.4185 ± 0.0687 | 1.3374 ± 0.0502 | 1.3719 ± 0.0601 | 1.1082 ± 0.0115 |

| M83 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 10.0817 | 0.1050 | 13.4742 ± 0.9039 | 1.0688 ± 0.0088 | 1.1567 ± 0.0201 | 1.0350 ± 0.0032 | 1.1653 ± 0.0217 | 1.1535 ± 0.0184 | 1.1514 ± 0.0194 | 1.0647 ± 0.0055 |

| M84 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 10.7198 | 0.1117 | 14.5524 ± 0.8771 | 1.0748 ± 0.0087 | 1.1702 ± 0.0197 | 1.0354 ± 0.0029 | 1.1808 ± 0.0215 | 1.1639 ± 0.0178 | 1.1646 ± 0.0191 | 1.0669 ± 0.0051 |

| M85 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 5.3937 | 0.0562 | 3.6984 ± 0.0103 | 1.0130 ± 0.0001 | 1.0284 ± 0.0001 | 1.0154 ± 0.0001 | 1.0263 ± 0.0001 | 1.0311 ± 0.0002 | 1.0269 ± 0.0001 | 1.0254 ± 0.0001 |

| M86 | 25.0 | 69.0 | 72 | 24.0 | 6.0946 | 0.0635 | 26.4064 ± 2.2952 | 1.4334 ± 0.0725 | 1.9860 ± 0.1641 | 1.1928 ± 0.0230 | 2.0492 ± 0.1788 | 1.9453 ± 0.1472 | 1.9537 ± 0.1592 | 1.2770 ± 0.0331 |

References

- Kelessidis, V.C.; Mpandelis, G. Measurements and prediction of terminal velocity of solid spheres falling through stagnant pseudoplastic liquids. Powder Technol. 2004, 147, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Z.; Cao, L.; Gao, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wu, D.; Huo, Z.; Zhao, X. Prediction of settling velocity of microplastics by multiple machine-learning methods. Water 2024, 16, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, G.; Pang, Z.; Zhu, Z. A new model for predicting drag coefficient and settling velocity of spherical and non-spherical particle in Newtonian fluid. Powder Technol. 2017, 321, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, H.; Portnikov, D. Free falling of non-spherical particles in Newtonian fluids, A: Terminal velocity and drag coefficient. Powder Technol. 2024, 434, 119357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.; Hassan, M.S.; Wong, W.; Chen, T. Revisit of the wall effect on the settling of cylindrical particles in the inertial regime. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 8870–8876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arsenijevic, Z.L.; Grbavcic, Z.B.; Garic-Grulovic, R.V.; Zdanski, F.K. Determination of non-spherical particle terminal velocity using particulate expansion data. Powder Technol. 1999, 103, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.; Levenspiel, O. Drag coefficient and terminal velocity of spherical and nonspherical particles. Powder Technol. 1989, 58, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, N.S. Simplified settling velocity formula for sediment particle. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1997, 123, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.H.; He, Y.L.; Yang, S.C.; Li, Y.Z. The settling characteristics and mean settling velocity of granular sludge in upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB)-like reactors. Biotechnol. Lett. 2006, 28, 1673–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyao, S.; Tingting, W.; Fumin, X.; Ruijie, L. A simple formula for predicting settling velocity of sediment particles. Water Sci. Eng. 2008, 1, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Helbar, S.M.; Amiri-Tokaldany, E.; Darby, S.; Shafaie, A. Fall Velocity of Sediment Particles. In Proceedings of the 4th IASME/WSEAS International Conference on Water Resources, Hydraulics & Hydrology (WHH’09), Cambridge, UK, 24–26 February 2009; Available online: https://www.wseas.us/e-library/conferences/2009/cambridge/WHH/WHH06.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Xu, Z.; Song, X.; Li, G.; Pang, Z.; Zhu, Z. Settling behavior of non-spherical particles in power-law fluids: Experimental study and model development. Particuology 2019, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ji, G.; Li, Z.; Ju, G. An improved model for predicting the drag coefficient and terminal settling velocity of natural sands in Newtonian fluid. Processes 2022, 10, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shen, K.; Zhang, K.; Guo, N.; Li, Z. A new model for predicting drag coefficient and settling velocity of coarse mineral particles in Newtonian fluid. Minerals 2024, 14, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandhal, P.S.; Lee, D.Y. An evaluation of the bulk specific gravity for granular materials. Highw. Res. Rec. 1970, 307, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Halagy, D.A.E. Studying the Factors Affecting the Drag Coefficient in Free Settling in Non-Newtonian Fluid. Master’s Thesis, College of Engineering, Nahrain University, Baghdad, Iraq, 2006. Available online: https://nahrainuniv.edu.iq/sites/default/files/Thesis_35.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Tassew, F.A.; Bergland, W.H.; Dinamarca, C.; Bakke, R. Settling velocity and size distribution measurement of anaerobic granular sludge using microscopic image analysis. J. Microbiol. Methods 2019, 159, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E.J.; Pronk, M.; van Loosdrecht, M.C. A settling model for full-scale aerobic granular sludge. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, A.A.; Portz, J.; Ward, M.; Beddow, J.K.; Vetter, A.F. A shape-modified size correction for terminal settling velocity in the intermediate region. Powder Technol. 1986, 48, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W. Modelling of Airflow and Aerosol Particle Movement in Buildings. Ph.D. Thesis, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK, 1995. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/228200016.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Bonadonna, C.; Ernst, G.G.J.; Sparks, R.S.J. Thickness variations and volume estimates of tephra fall deposits: The importance of particle Reynolds number. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1998, 81, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugbee, B.; Blonquist, M. Absolute and Relative Gas Concentration: Understanding Oxygen in Air. 2008. Available online: https://www.apogeeinstruments.com/content/AbsoluteandRelativeGasConcentration.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Yetilmezsoy, K. New explicit formulations for accurate estimation of aeration-related parameters in steady-state completely mixed activated sludge process. Glob. NEST J. 2017, 19, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Li, J.; Zhu, W.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Lv, M. Flight performance simulation and station-keeping endurance analysis for stratospheric super-pressure balloon in real wind field. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Liang, Y.; Wei, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, T. Research on the Formation Characteristics of Fog and Frost on Optical Windows of Unsealed Equipment Compartments in Aircrafts. Energies 2025, 18, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogbaike, S.O.; Badiee, A.; Gulzar, M.; Sohani, B.; Elseragy, A.; Elnokaly, A.; Mishra, R.; Aliyu, A.M. Optimal thermal comfort quantification in domestic indoor spaces under varying ambient and seasonal conditions—A numerical approach. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, M.; Zhou, L. Thermal Insulation of Radon Systems to Avoid Freezing. In Proceedings of the 7th International Building Physics Conference, IBPC2018, Syracuse, NY, USA, 23–26 September 2018; pp. 1073–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oivukkamäki, J.; Aalto, J.; Pfündel, E.E.; Tian, M.; Zhang, C.; Grebe, S.; Salmon, Y.; Hölttä, T.; Porcar-Castell, A. Field integration of shoot gas-exchange and leaf chlorophyll fluorescence measurements to study the long-term regulation of photosynthesis in situ. Tree Physiol. 2025, 45, tpae162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaterji, A.M.; Salilih, E.M.; Siddiqui, M.E.; Almatrafi, E.; Nurrohman, N.; Abulkhair, H.; Alsaiari, A.; Macedonio, F.; Wang, Z.; Albeirutty, M.; et al. Development of an integrated membrane condenser system with LNG cold energy for water recovery from humid flue gases in power plants. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 30791–30803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwen, J.; Schmidt, T.J.; Herranz, J. Impact of cathode components’ configuration on the performance of forward-bias bipolar membrane CO2-electrolyzers. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 4152–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, N.; Acar, H.İ.; Ertürk, L. Estimation of wind power potential in sivas cumhuriyet university campus using various probability density functions. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2025, 140, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Zamora, R.; Zhou, S.; Lie, T.-T. New Zealand Wind Speed and Power Potential Forecast: A case of Nelson. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Region 10 Symposium (TENSYMP), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–9 July 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetilmezsoy, K. Introduction of explicit equations for the estimation of surface tension, specific weight, and kinematic viscosity of water as a function of temperature. Fluid Mech. Res. Int. J. 2020, 4, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.; Karbasi, B.; Reiners, T.; Altieri, L.; Wagner, H.J.; Bertsch, V. Implementing prosumers into heating networks. Energy 2021, 230, 120844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetilmezsoy, K.; Bahramian, M.; Kıyan, E.; Bahramian, M. Development of a new practical formula for pipe-sizing problems within the framework of a hybrid computational strategy. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2021, 147, 04021012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlyssides, A.G.; Barampouti, E.M.P.; Mai, S.T. Simple estimation of granule size distribution and sludge bed porosity in a UASB reactor. Glob. NEST J. 2008, 10, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetilmezsoy, K.; Kıyan, E.; Ilhan, F. Synthesis of agro-industrial wastes/sodium alginate/bovine gelatin-based polysaccharide hydrogel beads: Characterization and application as controlled-release microencapsulated fertilizers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenijević, Z.L.; Grbavčić, Ž.B.; Garić-Grulović, R.V.; Bošković-Vragolović, N.M. Wall effects on the velocities of a single sphere settling in a stagnant and counter-current fluid and rising in a co-current fluid. Powder Technol. 2010, 203, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataíde, C.H.; Pereira, F.A.R.; Barrozo, M.A.S. Wall effects on the terminal velocity of spherical particles in Newtonian and non-Newtonian fluids. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 1999, 16, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetilmezsoy, K.; Sakar, S. Improvement of COD and color removal from UASB treated poultry manure wastewater using Fenton’s oxidation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 151, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fingas, M. A New Generation of Models for Water-in-Oil Emulsion Formation. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second Arctic and Marine Oil Spill Program (AMOP) Technical Seminar, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 9–11 June 2009; pp. 577–600. [Google Scholar]

- Yetilmezsoy, K.; Fingas, M.; Fieldhouse, B. An adaptive neuro-fuzzy approach for modeling of water-in-oil emulsion formation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2011, 389, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, R.V.; Bharat, S.; Deshpande, A.P.; Varughese, S.; Haridoss, P. Milling and separation of the multi-component printed circuit board materials and the analysis of elutriation based on a single particle model. Powder Technol. 2008, 183, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohdoh, A.M.; Aboulfotoh, A.M. Hydrodynamic characteristics of UASB granular sludge produced from combined anaerobic/aerobic treatment systems. Desalin. Water Treat. 2018, 124, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, O.J.I.; de Moel, P.J.; Raaghav, S.K.R.; Baars, E.T.; van Vugt, W.H.; Breugem, W.P.; Padding, J.T.; van der Hoek, J.P. Can terminal settling velocity and drag of natural particles in water ever be predicted accurately? Drink. Water Eng. Sci. 2021, 14, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.Y.; Zhang, D.W. Stokes shape factor and its application in the measurement of spherity of non-spherical particles. Powder Technol. 2001, 114, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.; Chuah, H.K.L. Dynamic shape factor for particles of various shapes in the intermediate settling regime. Adv. Powder Technol. 2013, 24, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwiti, F.; Gitau, A.; Mbuge, D. Evaluation of artificial neurocomputing algorithms and their metacognitive robustness in predictive modeling of fuel consumption rates during tillage. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Hang, T.; Song, Y.; Liang, K.; Zhu, S.; Fan, L. Assessment of small strain modulus in soil using advanced computational models. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yetilmezsoy, K. Application of random forest-based decision tree approach for modeling fully developed turbulent flow in rough pipes. Fluid Mech. Res. Int. J. 2023, 5, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetilmezsoy, K.; Ilhan, F.; Kıyan, E. Treatability of high-strength real sheep slaughterhouse wastewater using struvite precipitation coupled with Fenton’s oxidation: The MAPFOX process. Water Resour. Ind. 2023, 30, 100228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Solanki, C.H.; Reddy, K.R.; Shukla, S.K. (Eds.) Proceedings of the Indian Geotechnical Conference 2019: IGC-2019 Volume II; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2021; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.N.A.; Shukla, S.K. Predicting the settlement of geosynthetic-reinforced soil foundations using evolutionary artificial intelligence technique. Geotext. Geomembr. 2021, 49, 1280–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badescu, V. Assessing the performance of solar radiation computing models and model selection procedures. J. Atmos. Sol. Terr. Phys. 2013, 105, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Kumar, B.; Upadhyaya, S. Predicting and Mapping Flood Susceptibility: Leveraging Explainable AI and GIS Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE India Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (InGARSS), Goa, India, 2–5 December 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzinski, G.; Castello, A. Combining white box models, black box machines and humaninterventions for interpretable decision strategies. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2022, 17, 598–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistics | Set | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of data | TRA | 22,553 | 22,553 | 22,553 | 22,553 | 22,553 | 22,553 | 22,553 | 22,553 |

| TES | 5994 | 5994 | 5994 | 5994 | 5994 | 5994 | 5994 | 5994 | |

| ALL | 28,547 | 28,547 | 28,547 | 28,547 | 28,547 | 28,547 | 28,547 | 28,547 | |

| Mean | TRA | 22.5250 | 50.0736 | 1507.2761 | 20.7187 | 1.8614 | 0.1076 | 1.6148 | 9.8319 |

| TES | 22.5529 | 50.0664 | 1482.1361 | 20.7371 | 1.8405 | 0.1086 | 1.6228 | 9.8484 | |

| ALL | 22.5308 | 50.0721 | 1501.9975 | 20.7225 | 1.8570 | 0.1078 | 1.6165 | 9.8354 | |

| Standard deviation | TRA | 10.1327 | 23.1130 | 864.1437 | 10.0211 | 0.9835 | 0.0546 | 0.4355 | 5.6159 |

| TES | 10.1708 | 23.3512 | 861.5752 | 10.0488 | 0.9713 | 0.0547 | 0.4303 | 5.5723 | |

| ALL | 10.1405 | 23.1628 | 863.6507 | 10.0267 | 0.9810 | 0.0546 | 0.4344 | 5.6067 | |

| Coefficient of variation (CV) | TRA | 0.4498 | 0.4616 | 0.5733 | 0.4837 | 0.5284 | 0.5075 | 0.2697 | 0.5712 |

| TES | 0.4510 | 0.4664 | 0.5813 | 0.4846 | 0.5278 | 0.5031 | 0.2652 | 0.5658 | |

| ALL | 0.4501 | 0.4626 | 0.5750 | 0.4839 | 0.5283 | 0.5066 | 0.2687 | 0.5701 | |

| Standard error of mean | TRA | 0.0675 | 0.1539 | 5.7542 | 0.0667 | 0.0065 | 0.0004 | 0.0029 | 0.0374 |

| TES | 0.1314 | 0.3016 | 11.1285 | 0.1298 | 0.0125 | 0.0007 | 0.0056 | 0.0720 | |

| ALL | 0.0600 | 0.1371 | 5.1116 | 0.0593 | 0.0058 | 0.0003 | 0.0026 | 0.0332 | |

| Upper 95% CL of mean | TRA | 22.6572 | 50.3753 | 1518.5547 | 20.8495 | 1.8742 | 0.1083 | 1.6205 | 9.9052 |

| TES | 22.8104 | 50.6576 | 1503.9519 | 20.9916 | 1.8651 | 0.1100 | 1.6337 | 9.9895 | |

| ALL | 22.6484 | 50.3408 | 1512.0165 | 20.8389 | 1.8684 | 0.1085 | 1.6215 | 9.9004 | |

| Lower 95% CL of mean | TRA | 22.3927 | 49.7719 | 1495.9975 | 20.5879 | 1.8485 | 0.1069 | 1.6091 | 9.7586 |

| TES | 22.2953 | 49.4751 | 1460.3203 | 20.4827 | 1.8159 | 0.1072 | 1.6119 | 9.7073 | |

| ALL | 22.4132 | 49.8034 | 1491.9785 | 20.6062 | 1.8456 | 0.1072 | 1.6114 | 9.7703 | |

| Geometric mean | TRA | 19.8141 | 43.6347 | 1119.6819 | 18.0170 | 1.6152 | 0.0891 | 1.5574 | 7.8300 |

| TES | 19.8143 | 43.4541 | 1095.9313 | 18.0091 | 1.5988 | 0.0900 | 1.5667 | 7.9313 | |

| ALL | 19.8142 | 43.5968 | 1114.6526 | 18.0154 | 1.6117 | 0.0893 | 1.5594 | 7.8512 | |

| Skewness | TRA | −0.0041 | −0.0046 | 0.0014 | 0.2167 | 0.8822 | −0.0553 | 0.3816 | 0.4247 |

| TES | −0.0197 | −0.0170 | 0.0433 | 0.1992 | 0.9028 | −0.0814 | 0.3474 | 0.4456 | |

| ALL | −0.0074 | −0.0073 | 0.0102 | 0.2130 | 0.8866 | −0.0608 | 0.3744 | 0.4290 | |

| Kurtosis | TRA | 1.7897 | 1.7981 | 1.8053 | 1.8648 | 3.3205 | 1.8160 | 1.9105 | 2.4393 |

| TES | 1.7688 | 1.7792 | 1.8088 | 1.8433 | 3.3929 | 1.8246 | 1.9059 | 2.4445 | |

| ALL | 1.7853 | 1.7942 | 1.8056 | 1.8602 | 3.3356 | 1.8176 | 1.9093 | 2.4405 | |

| Maximum | TRA | 39.9992 | 89.9944 | 2999.8993 | 39.9998 | 4.9977 | 0.2000 | 2.4999 | 27.8533 |

| TES | 39.9990 | 89.9837 | 2999.2305 | 39.9990 | 4.9870 | 0.2000 | 2.4999 | 28.6014 | |

| ALL | 39.9992 | 89.9944 | 2999.8993 | 39.9998 | 4.9977 | 0.2000 | 2.4999 | 28.6014 | |

| Upper quartile | TRA | 31.3631 | 70.1306 | 2256.7097 | 29.0465 | 2.4170 | 0.1548 | 1.9710 | 13.8175 |

| TES | 31.4545 | 70.6175 | 2227.2445 | 29.1553 | 2.3861 | 0.1560 | 1.9732 | 13.9038 | |

| ALL | 31.3855 | 70.2436 | 2251.7023 | 29.0759 | 2.4121 | 0.1551 | 1.9714 | 13.8328 | |

| Median | TRA | 22.5714 | 50.1319 | 1506.9066 | 19.7904 | 1.6796 | 0.1089 | 1.5418 | 9.1987 |

| TES | 22.6430 | 50.5305 | 1466.5721 | 19.9361 | 1.6576 | 0.1102 | 1.5653 | 9.1661 | |

| ALL | 22.5872 | 50.1897 | 1499.3463 | 19.8160 | 1.6748 | 0.1091 | 1.5459 | 9.1902 | |

| Lower quartile | TRA | 13.7062 | 30.1862 | 758.1586 | 11.9569 | 1.0906 | 0.0609 | 1.2247 | 5.3588 |

| TES | 13.6709 | 29.8828 | 736.5679 | 11.8753 | 1.0838 | 0.0625 | 1.2365 | 5.3912 | |

| ALL | 13.6967 | 30.1339 | 754.0141 | 11.9377 | 1.0891 | 0.0612 | 1.2279 | 5.3611 | |

| Minimum | TRA | 5.0025 | 10.0023 | 2.0189 | 5.0043 | 0.5001 | 0.0100 | 1.0015 | 0.1001 |

| TES | 5.0036 | 10.0282 | 2.1118 | 5.0071 | 0.5004 | 0.0100 | 1.0018 | 0.1001 | |

| ALL | 5.0025 | 10.0023 | 2.0189 | 5.0043 | 0.5001 | 0.0100 | 1.0015 | 0.1001 | |

| Range | TRA | 34.9967 | 79.9921 | 2997.8804 | 34.9955 | 4.4976 | 0.1900 | 1.4984 | 27.7532 |

| TES | 34.9954 | 79.9555 | 2997.1187 | 34.9919 | 4.4866 | 0.1900 | 1.4981 | 28.5013 | |

| ALL | 34.9967 | 79.9921 | 2997.8804 | 34.9955 | 4.4976 | 0.1900 | 1.4984 | 28.5013 | |

| Interquartile range | TRA | 17.6569 | 39.9444 | 1498.5511 | 17.0896 | 1.3264 | 0.0939 | 0.7463 | 8.4587 |

| TES | 17.7836 | 40.7347 | 1490.6766 | 17.2800 | 1.3023 | 0.0935 | 0.7367 | 8.5126 | |

| ALL | 17.6888 | 40.1097 | 1497.6882 | 17.1382 | 1.3230 | 0.0939 | 0.7435 | 8.4717 |

| Category | Sub-Category | Material |

|---|---|---|

| Grains & Cereals (n = 37) | Cereal Grains (n = 5) | M2: Baldo Rice Grain (Oryza sativa), M21: Corn Grain (Zea mays), M46: Karacadağ Rice Grains (Oryza sativa), M61: Quinoa Seeds (Chenopodium quinoa), M73: Wheat Kernel (Triticum aestivum) |

| Pulses (n = 7) | M3: Black Bean Piece (Phaseolus vulgaris), M28: Dwarf Pot Pea Seed (Pisum sativum), M41: Green Lentil (Lens culinaris), M45: Kabuli Chickpea (Cicer arietinum), M51: Mung Bean (Vigna radiata), M62: Red Lentil (Lens culinaris), M76: Yellow Lentil (Lens culinaris) | |

| Cereal Derivatives (n = 5) | M25: Dried Tarhana Crumbs, M29: Egg Noodle Pieces, M30: Extra Grain Bulgur (Triticum durum), M54: Orzo Pasta, M58: Pounded and Husked Wheat Kernel (Triticum durum) | |

| Oilseeds (n = 7) | M7: Black Sesame Seeds (Sesamum indicum), M16: Chia Seeds (Salvia hispanica), M32: Flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum), M52: Mustard Seeds (White Mustard) (Sinapis alba), M75: White Sesame Seeds (Sesamum indicum), M63: Roasted Sunflower Kernel (Helianthus annuus), M59: Raw Pumpkin Seed Kernel (Cucurbita pepo) | |

| Spices & Herbs (n = 13) | M4: Black Cumin Seeds (Nigella sativa), M5: Black Peppercorn (Piper nigrum), M11: Broad-leaved Sage Seeds (Salvia officinalis), M15: Cardamom Seeds (Elettaria cardamomum), M19: Clove Bud (Syzygium aromaticum), M20: Clove Stem Pieces (Syzygium aromaticum), M33: Garden Cress Seeds (Lepidium sativum), M34: Genovese Basil Seeds (Ocimum basilicum), M35: Giant Red Leaf Mustard Seeds (Brown/Indian Mustard) (Brassica juncea), M39: Green Beefsteak Plant Seeds (Perilla frutescens), M49: Leek Seeds (Allium porrum), M68: Syrian Rue Seeds (Peganum harmala), M74: White Peppercorn (Piper nigrum) | |

| Seeds & Pits (n = 18) | Fruit & Vegetable Seeds (n = 12) | M77: Apple Seed (Malus domestica, Amasya Misket Variety), M8: Blackberry Seeds (Rubus fruticosus), M10: Blue Poppy Seeds (Papaver somniferum), M17: Chili Pepper Seeds (Capsicum annuum), M26: Dried Wild Fig Seeds (Ficus carica), M27: Dwarf Green Pear Seed (Pyrus communis), M38: Grape Seed (Vitis vinifera), M47: Kiwano (Horned Melon) Seed (Cucumis metuliferus), M48: Kiwi Seeds (Actinidia deliciosa), M85: Lemon Seeds (Citrus limon, Seed Coat Intact), M50: Mini Watermelon Seeds (Citrullus lanatus), M69: Tamarind Seed (Tamarindus indica) |

| Pits & Shells (n = 6) | M12: Buckthorn Seed (Rhamnus catharticus), M78: Giresun Hazelnut Shell Piece (Corylus avellana), M43: Jerusalem Date Pit Piece (Phoenix dactylifera), M60: Olive Pit (Olea europaea, Large Reddish-Brown Olive), M57: Pine Kernel (Pinus pinea), M65: Siirt Pistachio Shell Piece (Pistacia vera) | |

| Processed Food Products (n = 11) | Confectionery (n = 6) | M31: Flat Square Chocolate Pieces, M79: Large Ovoid Almond-Filled Dragee, M81: Medium Mixed Fruit-Flavored Hard Candy, M80: Milk-Filled Fruit-Flavored Candy, M82: Mini Fruit-Flavored Hard Candy, M64: Rose-flavored Turkish Delight Pieces |

| Fruit-Derived Products (n = 4) | M24: Currant (Vitis vinifera), M84: Dried Cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon), M83: Golden Raisins (Vitis vinifera, Sultana), M55: Pale Yellow Pomegranate Aril (Punica granatum) | |

| Animal Feed (n = 1) | M67: Sinking Fish Food Crumbles | |

| Mineral & Chemical Products (n = 4) | Salt & Crystals (n = 3) | M18: Citric Acid Crystals, M37: Granular Himalayan Salt, M86: Sodium Hydroxide Pellets (NaOH, 95% Purity) |

| Adsorbents & Desiccants (n = 1) | M66: Silica Gel Desiccant Beads | |

| Industrial Products (n = 11) | Thermoplastic & Resins (n = 3) | Black Plastic Cable Tie Pieces (214 TCA), Holed Plastic Bead, Transparent Tube Pieces |

| Elastomers (n = 3) | M6: Black Plastic Cable Tie Pieces (214 TCA), M42: Holed Plastic Bead, M71: Transparent Tube Pieces | |

| Metals and Alloys (n = 1) | M53: Nail Clipper Ball Chain Beads (Holed) | |

| Petroleum/Synthetic Derivatives (n = 1) | M72: Wax Piece | |

| Composite Materials (n = 3) | M13: Cable Pieces (No Wires), M14: Cable Pieces (With Wires), M22: Cotton Swab Stick Pieces | |

| Carbonaceous Products (n = 2) | Natural (n = 1) | M36: Granular Activated Carbon (Coconut Shell-Based) |

| Pelletized (n = 1) | M1: Activated Carbon Pellet | |

| Animal-Based Products (n = 2) | Animal Products (n = 1) | M23: Crushed Eggshell Pieces |

| Leather (n = 1) | M70: Tanned Black Cowhide Pieces | |

| Hygiene & Cleaning Products (n = 1) | Soaps & Detergents (n = 1) | M44: Juniper Tar Soap Pieces |

| Statistics | Equation (22) | Equation (24) | Equation (25) | Equation (27) | Equation (29) | Equation (31) | Equation (83) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9572 | 0.9560 | 0.9877 | 0.9470 | 0.9412 | 0.9531 | 0.9951 | |

| (slope) | 1.0889 | 0.6907 | 1.2245 | 0.7016 | 0.6274 | 0.7038 | 0.9954 |

| 0.9572 | 0.9560 | 0.9877 | 0.9469 | 0.9411 | 0.9531 | 0.9951 | |

| MAE | 2.6857 | 1.9054 | 1.3406 | 1.6740 | 2.2332 | 1.7213 | 0.3126 |

| MBE | 2.6855 | −1.7794 | 1.3185 | −1.3708 | −1.9702 | −1.4908 | −0.0013 |

| NMBE | 27.2687 | −18.0680 | 13.3877 | −13.9193 | −20.0053 | −15.1379 | −0.0130 |

| RMSE | 3.0169 | 2.6110 | 1.9706 | 2.3448 | 2.9924 | 2.3879 | 0.3912 |

| RMSES | 2.7309 | 2.4772 | 1.8176 | 2.1548 | 2.8619 | 2.2240 | 0.0257 |

| RMSEU | 1.2823 | 0.8252 | 0.7615 | 0.9247 | 0.8740 | 0.8695 | 0.3903 |

| SEE | 1.2825 | 0.8253 | 0.7616 | 0.9249 | 0.8742 | 0.8696 | 0.3904 |

| PSE | 4.5357 | 9.0127 | 5.6975 | 5.4299 | 10.7224 | 6.5430 | 0.0043 |

| WIOA | 0.9375 | 0.9268 | 0.9751 | 0.9408 | 0.8980 | 0.9390 | 0.9988 |

| FV | −0.1069 | 0.3441 | −0.2080 | 0.3243 | 0.4290 | 0.3244 | 0.0022 |

| FA2 | 0.7578 | 1.1703 | 0.9124 | 1.1088 | 1.1849 | 1.1255 | 1.0028 |

| CV(RMSE) | 0.3063 | 0.2651 | 0.2001 | 0.2381 | 0.3038 | 0.2425 | 0.0397 |

| NSE | 0.7068 | 0.7804 | 0.8749 | 0.8229 | 0.7116 | 0.8163 | 0.9951 |

| LMI | 0.4203 | 0.5887 | 0.7106 | 0.6387 | 0.5180 | 0.6285 | 0.9325 |

| MFB | 28.3663 | −14.4588 | 9.4323 | −8.8668 | −14.7681 | −10.4124 | 0.0459 |

| MFE | 28.3670 | 18.2335 | 9.8870 | 16.1945 | 22.2200 | 16.6862 | 5.0212 |

| AIC | 13,253.6438 | 11,521.3733 | 8148.2319 | 10,232.3703 | 13,155.8995 | 10,450.5987 | −11,236.5633 |

| t statistic | 151.2329 | 72.0919 | 69.6903 | 55.7840 | 67.7180 | 61.8722 | 0.2531 |

| GPI | 8.4033 | −2.2933 | 0.3333 | −1.4541 | −3.7603 | −1.5838 | 8.82 × 10−8 |

| RPD | 1.8470 | 2.1341 | 2.8276 | 2.3764 | 1.8621 | 2.3335 | 14.2457 |

| RI | 2.0699 | 1.2686 | 1.8246 | 1.3419 | 1.2344 | 1.3204 | 1.5877 |

| VAF | 95.0860 | 76.4306 | 95.4488 | 77.5739 | 60.9347 | 78.4337 | 99.5050 |

| PI | −1.1088 | −0.8907 | −0.0285 | −0.6221 | −1.4419 | −0.6504 | 1.5990 |

| IOS | 0.3063 | 0.2651 | 0.2001 | 0.2381 | 0.3038 | 0.2425 | 0.0397 |

| index | 0.3662 | 0.5257 | 0.9458 | 0.6096 | 0.4111 | 0.5891 | 0.9565 |

| OAS | 3.6904 | 3.7906 | 4.6708 | 4.1409 | 3.2665 | 4.0770 | 6.7347 |

| 0.1604 | 0.1558 | 0.1496 | 0.1530 | 0.1601 | 0.1535 | 0.1414 | |

| 2.6855 | −1.7794 | 1.3185 | −1.3708 | −1.9702 | −1.4908 | −0.0013 | |

| ±1.96 × | 2.6946 | 3.7455 | 2.8709 | 3.7290 | 4.4149 | 3.6564 | 0.7667 |

| 95% PEI (LL) | −0.0091 | −5.5249 | −1.5524 | −5.0998 | −6.3851 | −5.1472 | −0.7680 |

| 95% PEI (UL) | 5.3802 | 1.9660 | 4.1893 | 2.3581 | 2.4447 | 2.1655 | 0.7654 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yetilmezsoy, K.; Ilhan, F.; Kıyan, E. An Integrated Methodology for Novel Algorithmic Modeling of Non-Spherical Particle Terminal Settling Velocities and Comprehensive Digital Image Analysis. Water 2025, 17, 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223268

Yetilmezsoy K, Ilhan F, Kıyan E. An Integrated Methodology for Novel Algorithmic Modeling of Non-Spherical Particle Terminal Settling Velocities and Comprehensive Digital Image Analysis. Water. 2025; 17(22):3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223268

Chicago/Turabian StyleYetilmezsoy, Kaan, Fatih Ilhan, and Emel Kıyan. 2025. "An Integrated Methodology for Novel Algorithmic Modeling of Non-Spherical Particle Terminal Settling Velocities and Comprehensive Digital Image Analysis" Water 17, no. 22: 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223268

APA StyleYetilmezsoy, K., Ilhan, F., & Kıyan, E. (2025). An Integrated Methodology for Novel Algorithmic Modeling of Non-Spherical Particle Terminal Settling Velocities and Comprehensive Digital Image Analysis. Water, 17(22), 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223268