Assessment of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation in the Semi-Arid Region of Oum El Bouaghi (Northeastern Algeria) Using Groundwater Quality and Pollution Indices and GIS Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

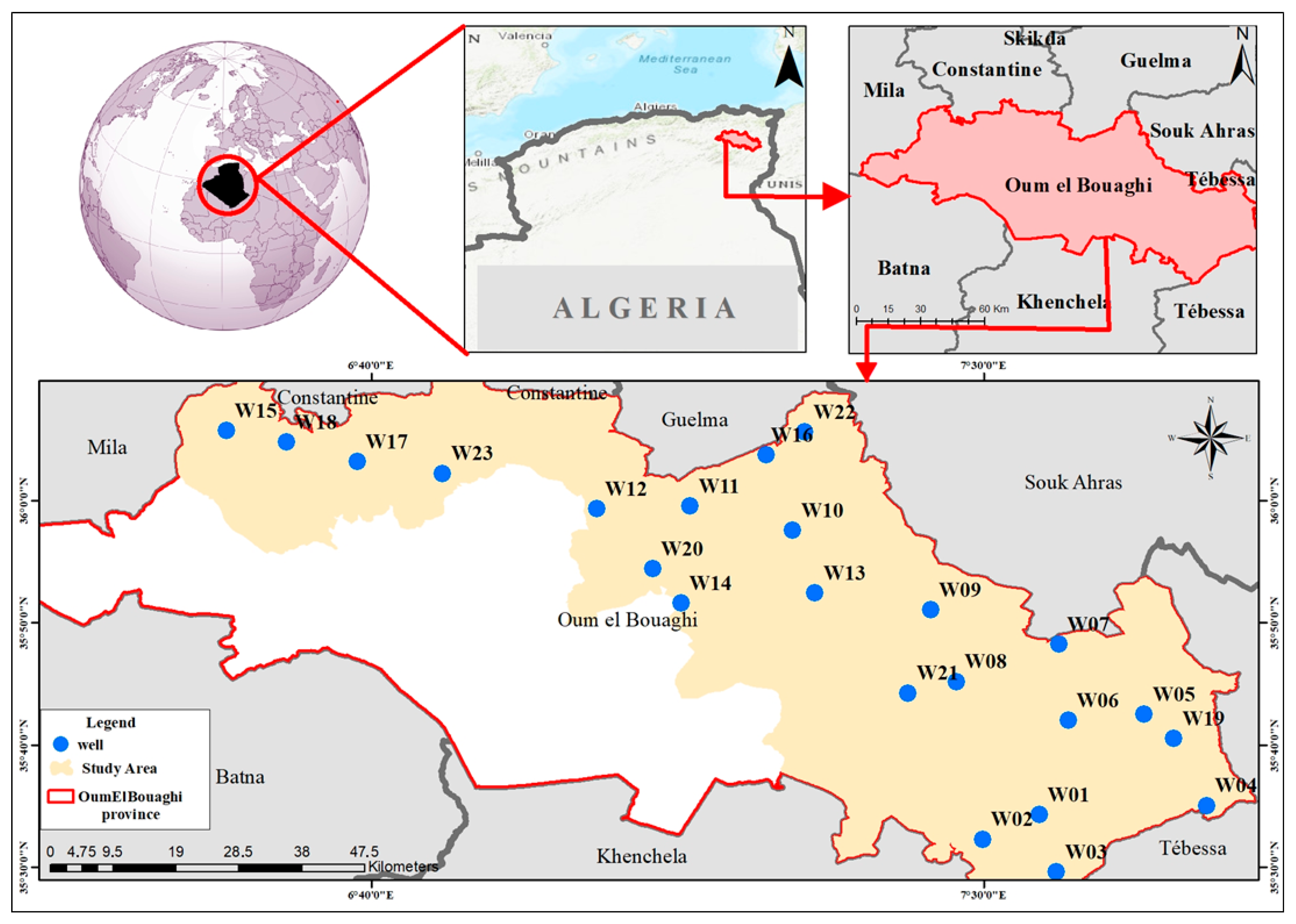

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.2.1. Piper Plot

2.2.2. Gibbs Diagram

2.2.3. Water Quality Assessment

2.2.4. Standard Irrigation Water Quality Index (IWQI)

2.2.5. Water Quality for Irrigation

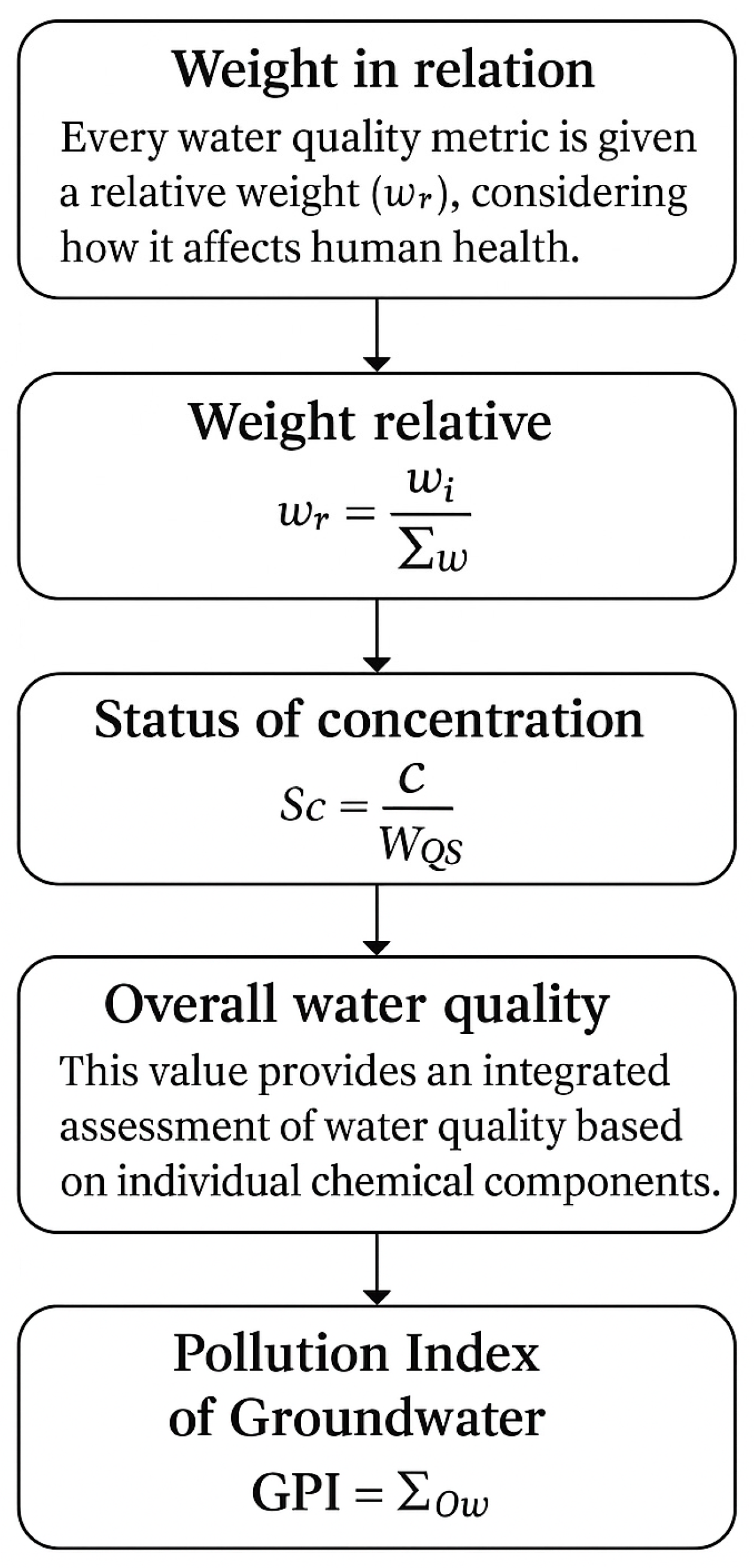

2.2.6. Groundwater Pollution Index (GPI)

2.2.7. Technical Interpolation

2.2.8. Pearson Correlation

3. Results

3.1. Groundwater Physicochemical Parameters

3.2. Hydrogeochemical Facies and Geochemistry Mechanism Controlling

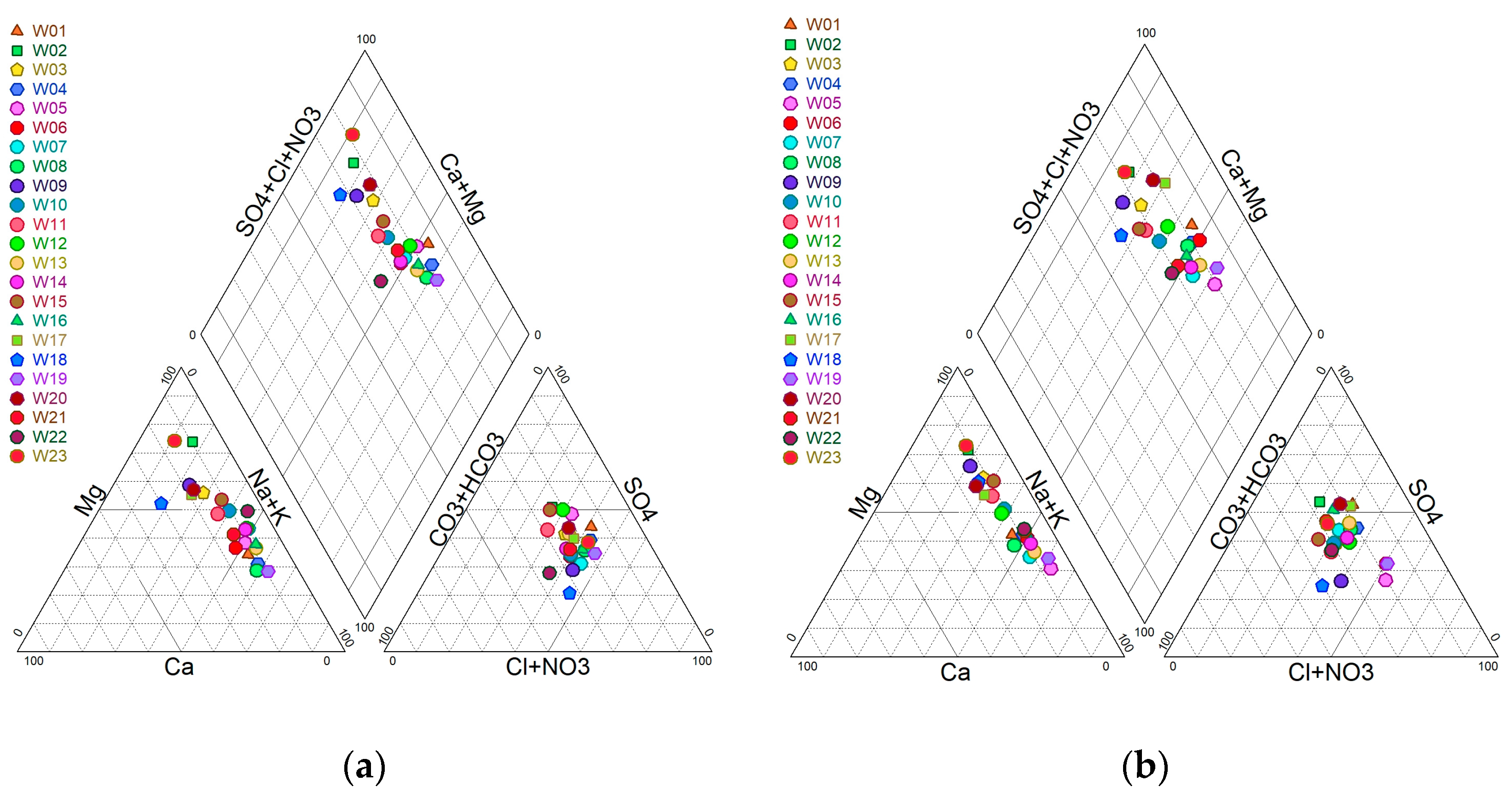

3.2.1. Piper Diagram

3.2.2. Data Plot on Gibbs Diagram

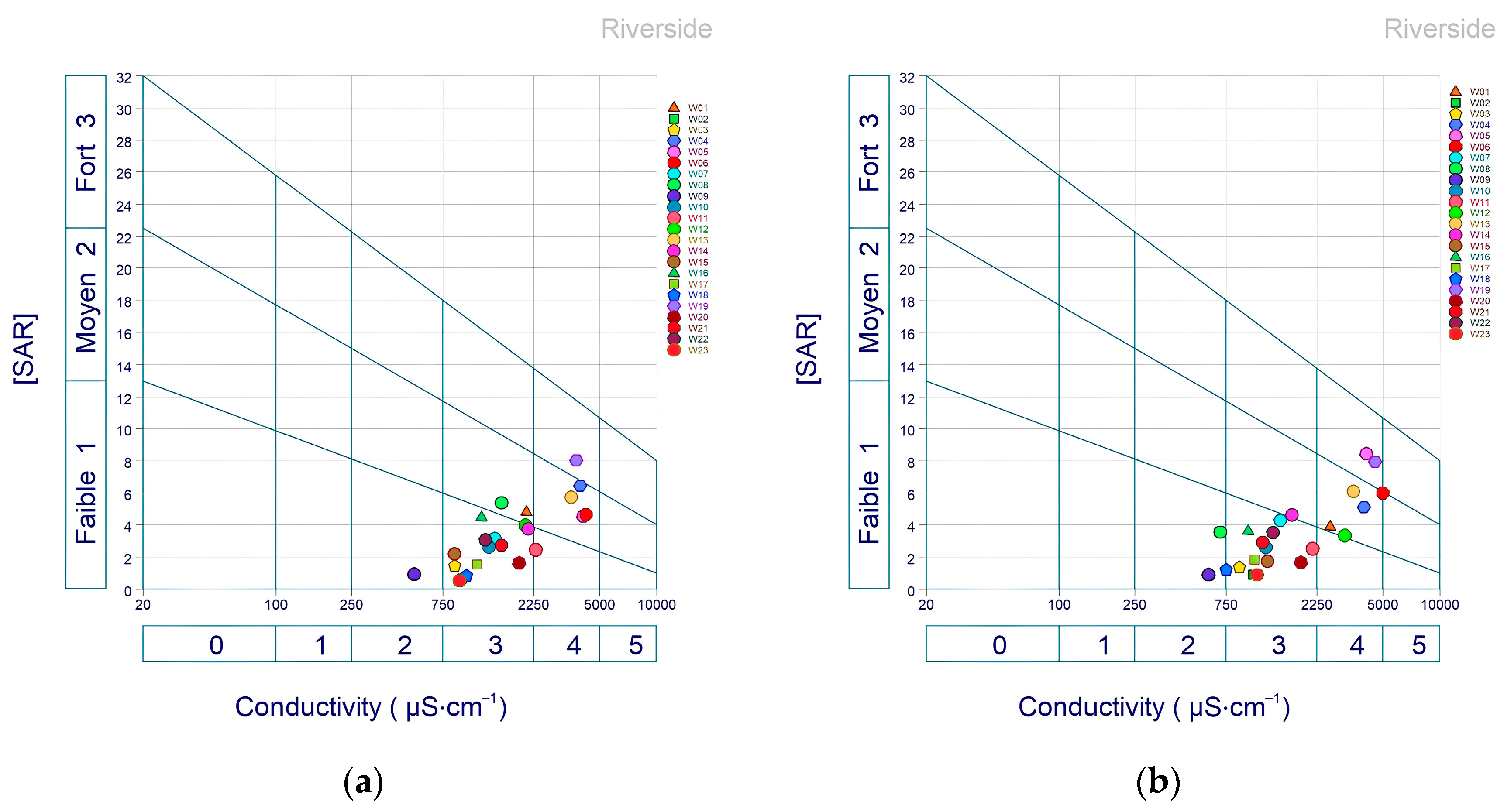

3.2.3. Riverside Diagram

3.2.4. Wilcox Diagram

3.3. Water Quality Indices

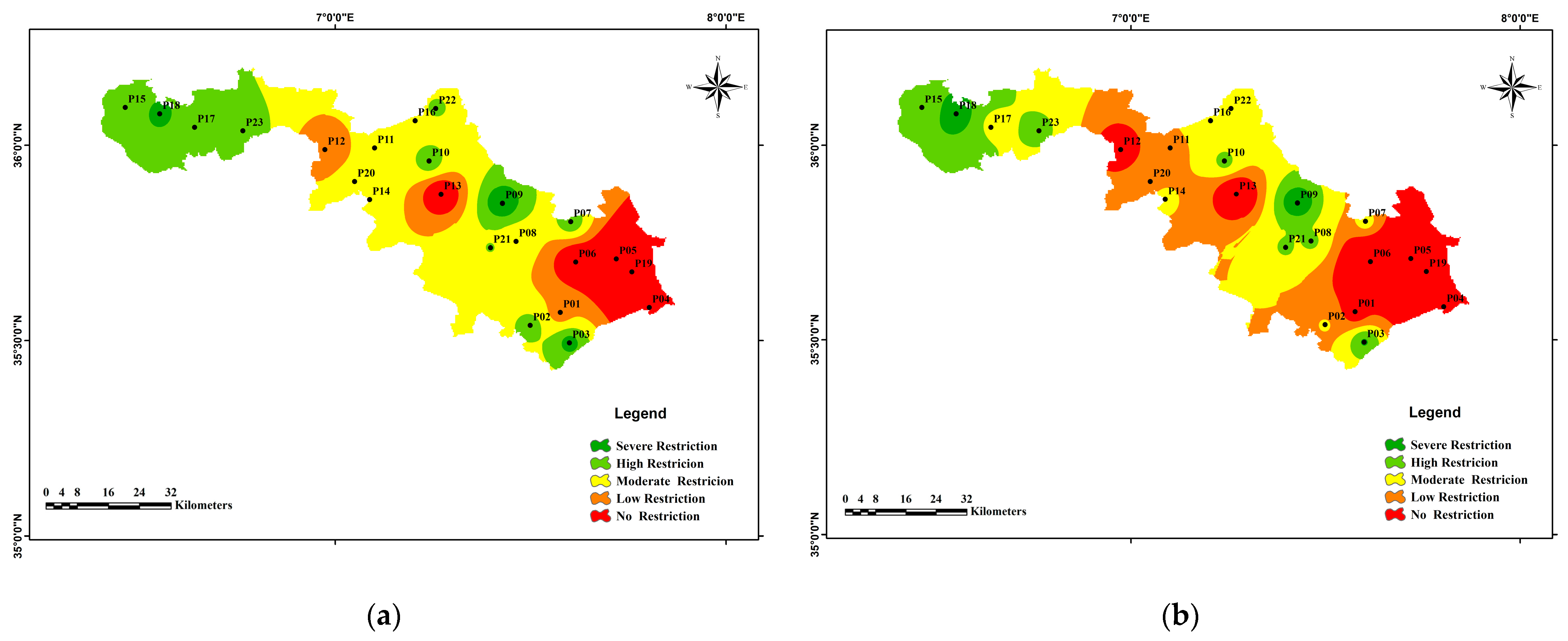

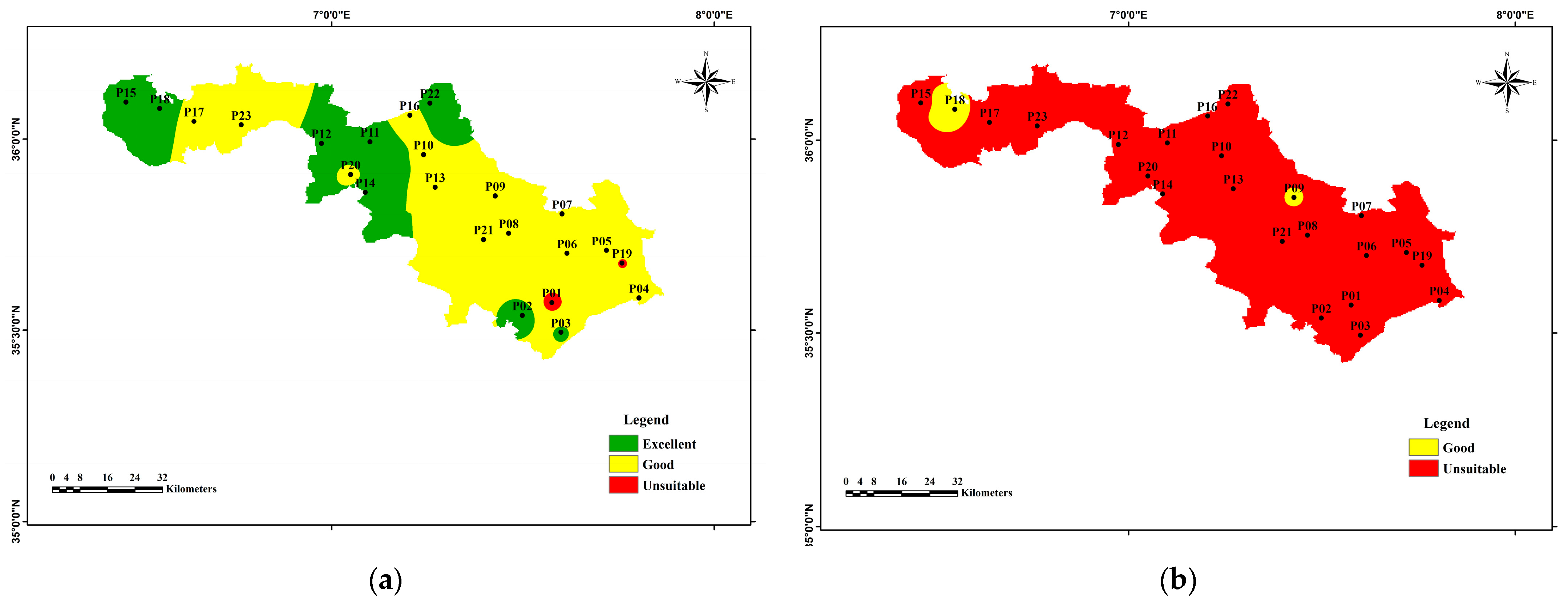

3.3.1. The Irrigation Water Quality Index (IWQI)

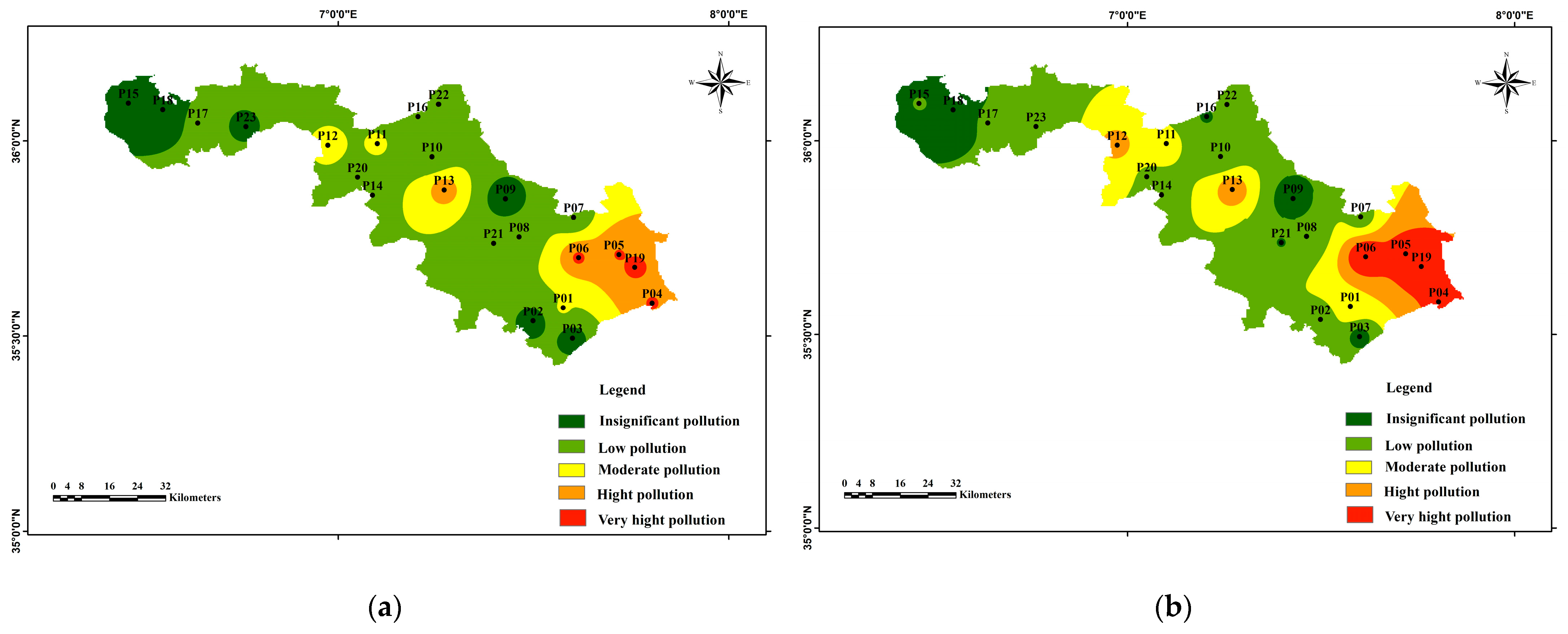

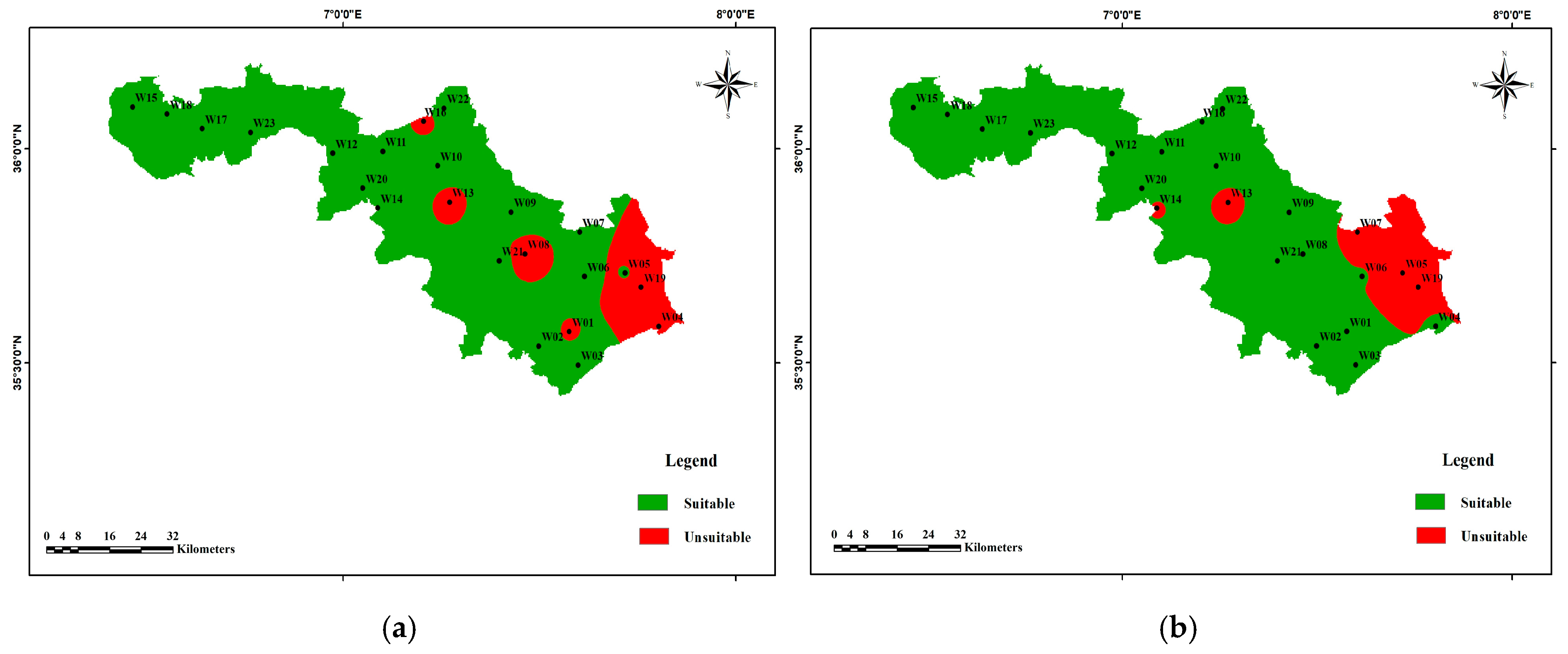

3.3.2. Calculation of Groundwater Pollution Index (GPI)

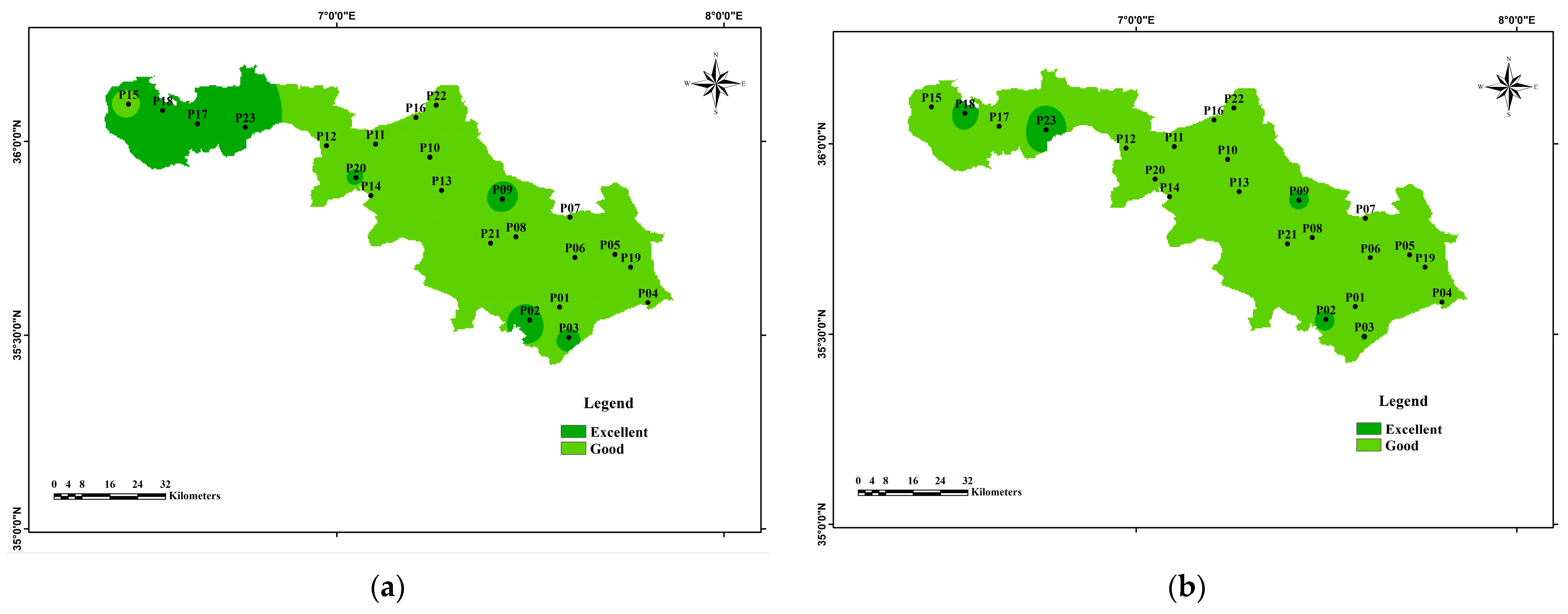

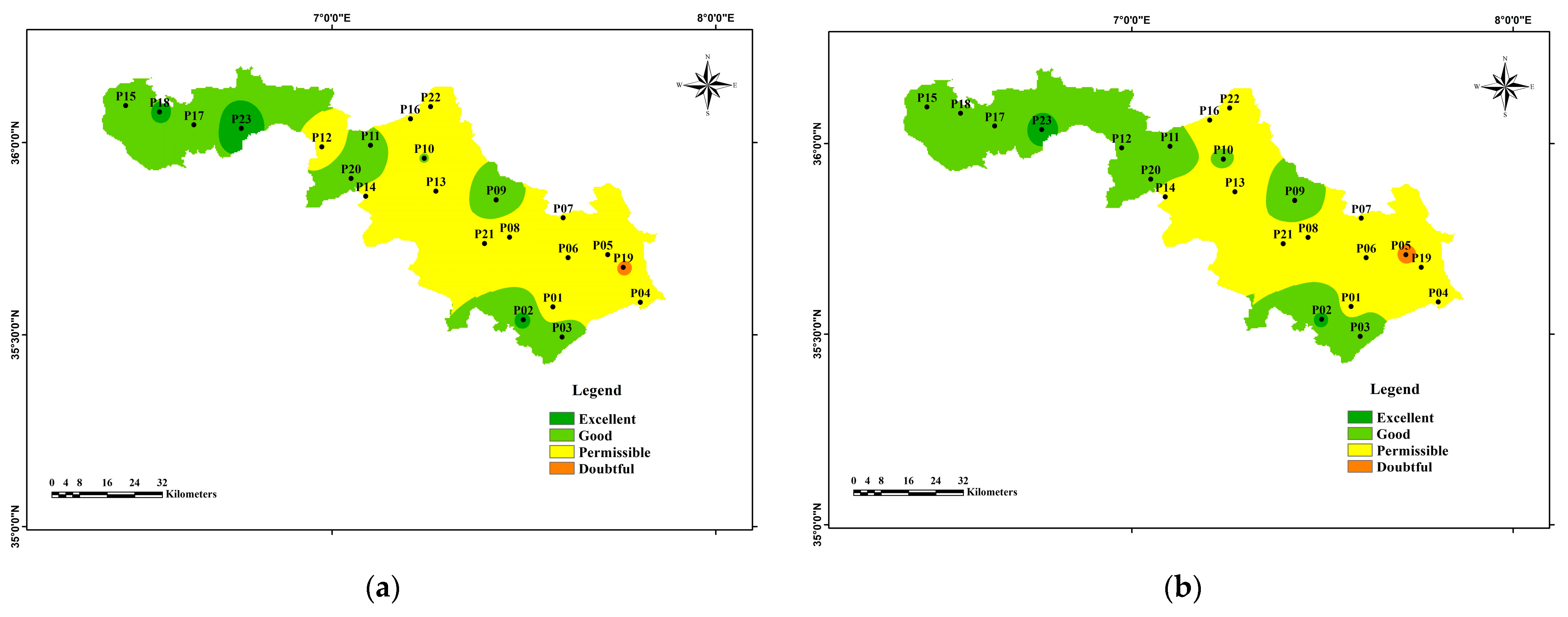

3.4. Water Quality Index for Irrigation

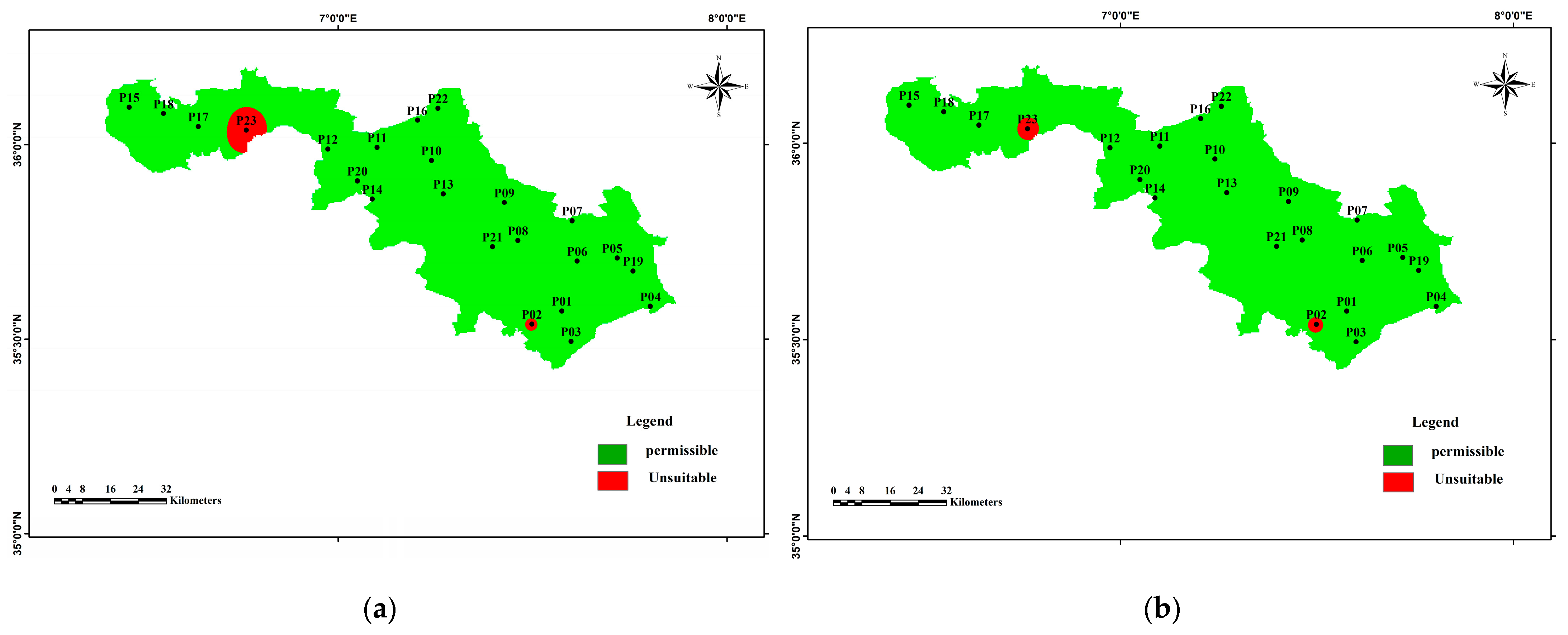

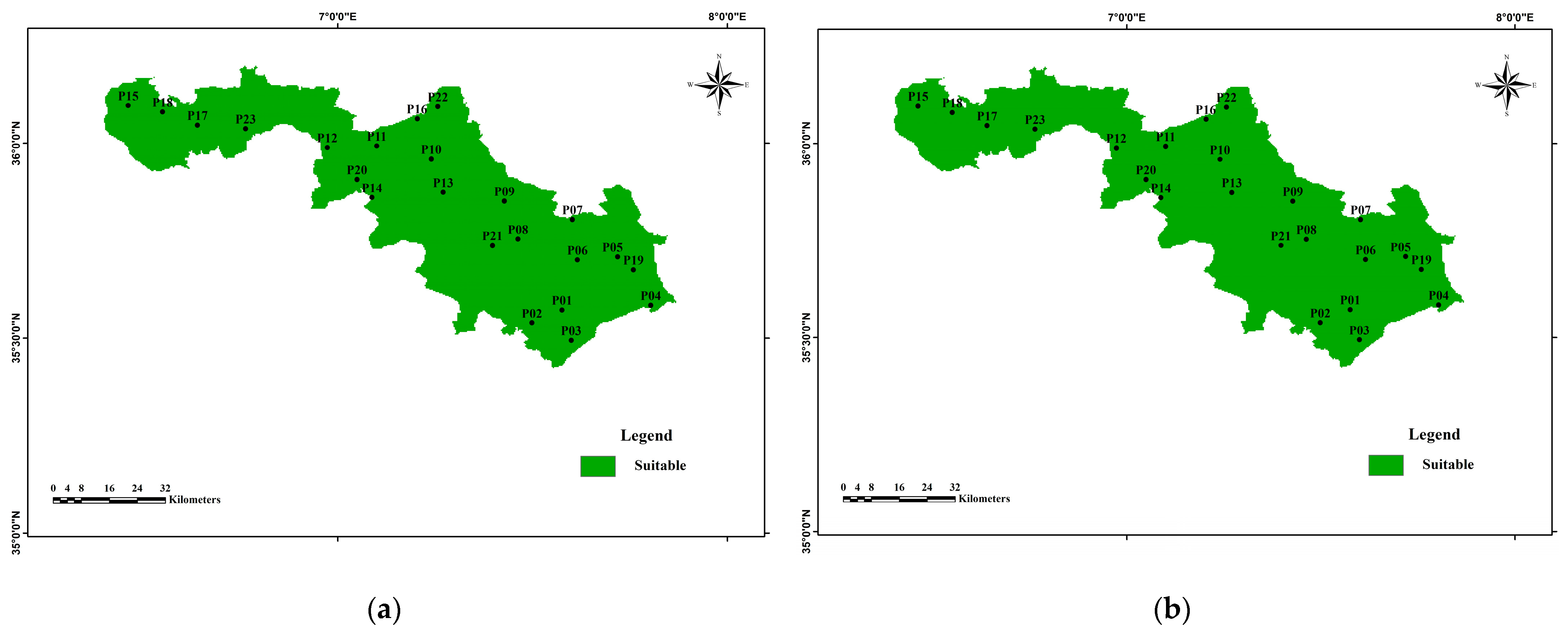

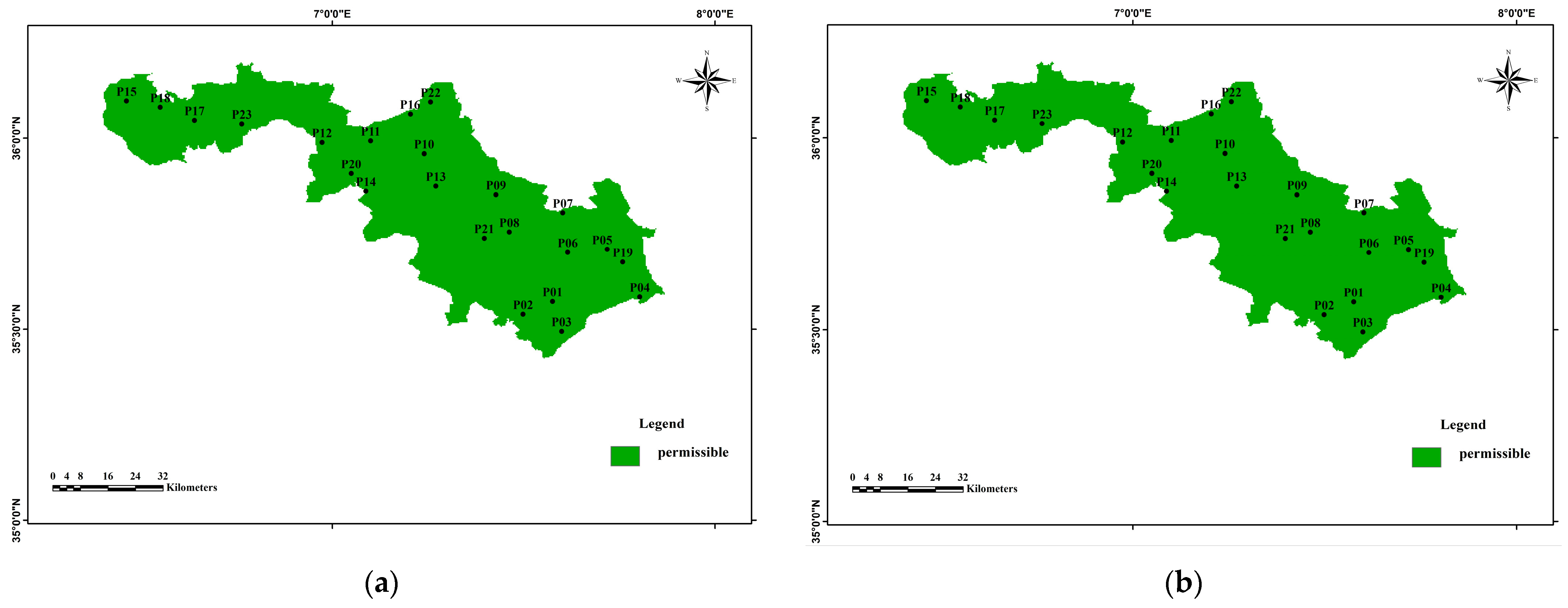

3.4.1. Sodium Adsorption Ratio (SAR)

3.4.2. Sodium Percent (Na%)

3.4.3. Permeability Index (PI)

3.4.4. Magnesium Hazard Ratio (MHR)

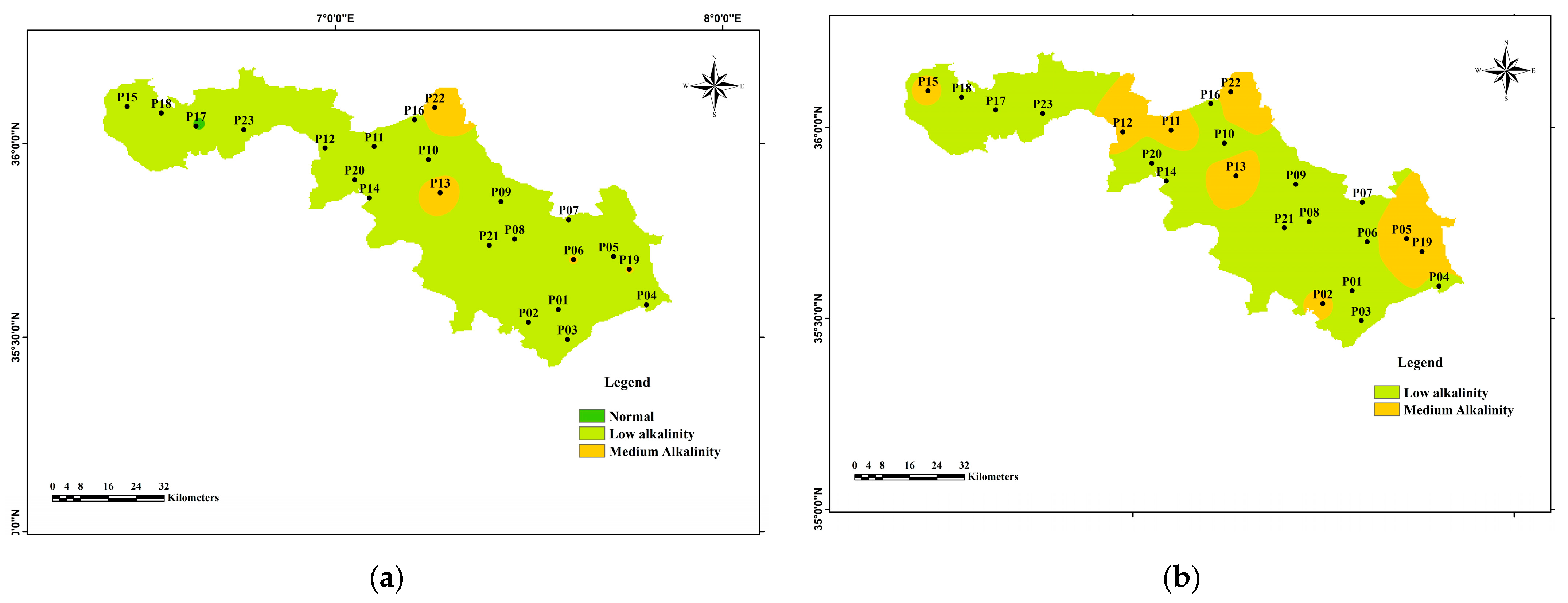

3.4.5. Residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC)

3.4.6. Kelley’s Ratio (KR)

3.4.7. Potential Salinity (PS)

3.4.8. Residual Sodium Bicarbonate (RSBC)

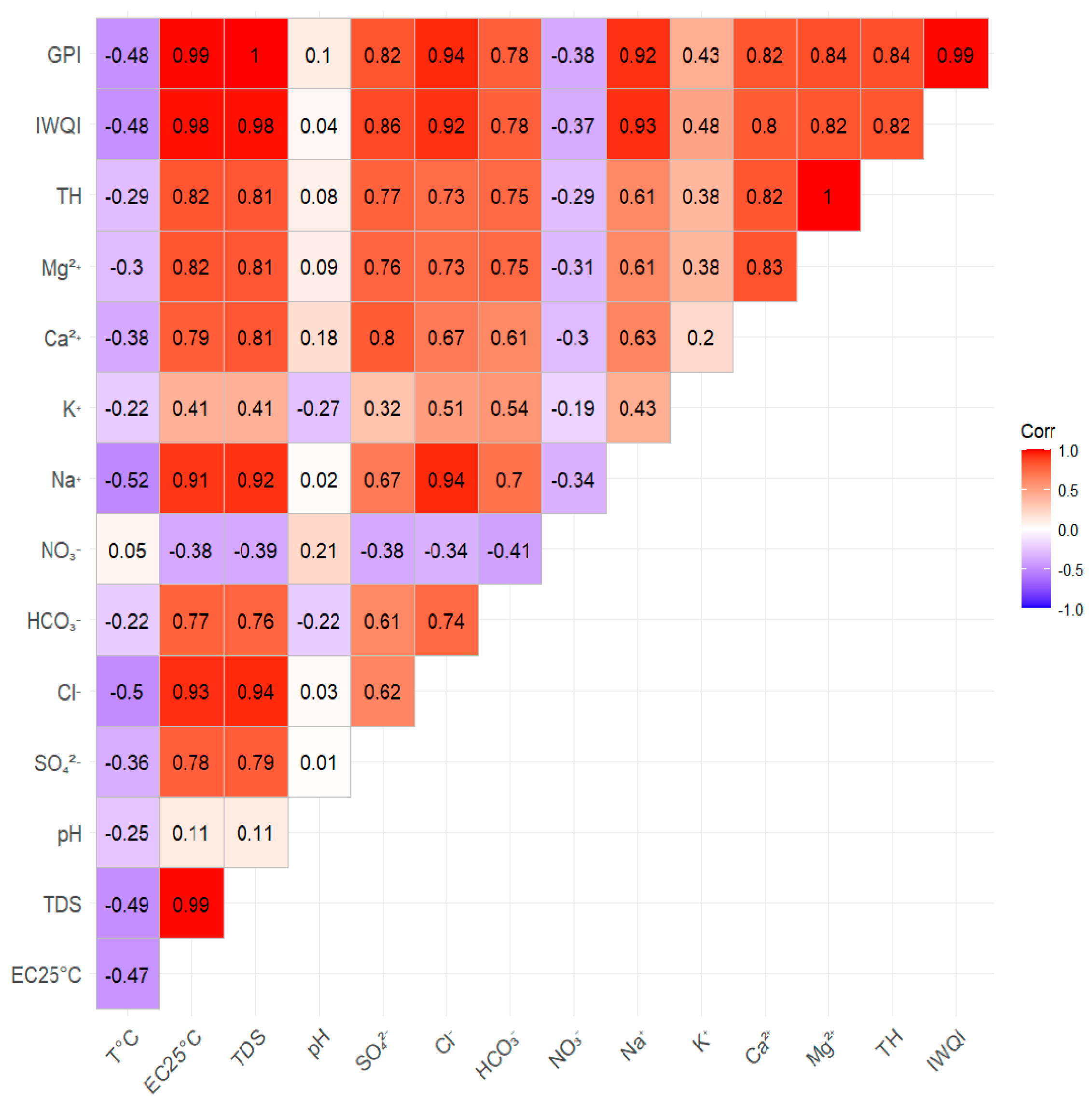

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- García-Rubio, N.; Larraz, B.; Gámez, M.; Raimonet, M.; Cakir, R.; Sauvage, S.; Sánchez Pérez, J.M. An economic valuation of the provisioning ecosystem services in the south-west of Europe. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N. Groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes and potential health risks assessment: A case study from semi-arid region of South India. Expo. Health 2019, 11, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Armanuos, A.M. Introduction to “Groundwater in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas”. In Groundwater in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouderbala, A.; Merouchi, H. Impact of climate change and human activities on groundwater resources in the Alluvial Aquifer of upper Cheliff, Algeria. Indian J. Ecol. 2023, 50, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, P.; Srivastava, J.; Charles, B.; Subramanian, S.R. Species distribution models to predict the potential niche shift and priority conservation areas for mangroves (Rhizophora apiculata, R. mucronata) in response to climate and sea level fluctuations along coastal India. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, K. Water-Related Diseases Responsible for 80 per Cent of All Illnesses, Deaths in Developing World; Nations Unies: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2003/sgsm8707.doc.htm (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Luo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Hao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; Dong, G. Groundwater geochemical signatures and implication for sustainable development in a typical endorheic watershed on Tibetan plateau. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 48312–48329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiyat, Z. Groundwater in the Arab region: Making the invisible visible. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 263, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L.A. Diagnosis and Improvement of Saline and Alkali Soils (Agricultural Handbook No. 60); United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, L.V. Classification and Use of Irrigation Waters (USDA Circular No. 969); United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Doneen, L.D. Notes on Water Quality in Agriculture; Department of Water Science and Engineering, University of California, Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, F.M. Significance of carbonate in irrigation waters. Soil Sci. 1950, 69, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, O.; Sikdar, P.K. Assessment of groundwater quality status by using water quality index and GIS technique in Ranchi city, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 2053–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aizari, H.S.; Aslaou, F.; Al-Aizari, A.R.; Al-Odayni, A.-B.; Al-Aizari, A.-J.M. Evaluation of Groundwater Quality and Contamination Using the Groundwater Pollution Index (GPI), Nitrate Pollution Index (NPI), and GIS. Water 2023, 15, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, R.S.; Zhang, J.; Li, P. Development of Irrigation Water Quality Index incorporating information entropy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3119–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mountassir, O.; Bahir, M.; Ouazar, D.; Chehbouni, A.; Carreira, P.M. Temporal and spatial assessment of groundwater contamination with nitrate using nitrate pollution index (NPI), groundwater pollution index (GPI), and GIS (case study: Essaouira basin, Morocco). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 17132–17149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Gaagai, A.; Agrama, A.A.; El-Fiqy, W.F.M.; Eid, M.H.; Szűcs, P.; Elsayed, S.; Elsherbiny, O.; Khadr, M.; Abukhadra, M.R.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation and prediction of groundwater quality and risk indices using quantitative approaches, multivariate analysis, and machine learning models: An exploratory study. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singaraja, C. Relevance of water quality index for groundwater quality evaluation: Thoothukudi District, Tamil Nadu, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 2157–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaagai, A.; Aouissi, H.A.; Bencedira, S.; Hinge, G.; Athamena, A.; Heddam, S.; Gad, M.; Elsherbiny, O.; Elsayed, S.; Eid, M.H. Application of water quality indices, machine learning approaches, and GIS to identify groundwater quality for irrigation purposes: A case study of Sahara Aquifer, Doucen Plain, Algeria. Water 2023, 15, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madene, E.; Boufekane, A.; Meddi, M.; Busico, G.; Zghibi, A. Spatial analysis and mapping of the groundwater quality index for drinking and irrigation purposes in the alluvial aquifers of the Upper and Middle Cheliff Basin (north-west Algeria). Water Supply 2022, 22, 4422–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennia, K. Évaluation De La Qualité Des Eaux Souterraines Dans le Bassin Versant De Hennaya (Algérie): Application De L’indice De Qualité De L’eau (WQI) et Analyse Géospatiale. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Hassiba Benbouali de Chlef, Chlef, Algeria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bouderbala, A. Human impact of septic tank effluent on groundwater quality in the rural area of Ain Soltane (Ain Defla), Algeria. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2019, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djema, M.; Mebrouk, N. Groundwater quality and nitrate pollution in the Nador plain, Algeria. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteldjaoui, F.; Bessenasse, M.; Kettab, A.; Scheytt, T. Combining geology, hydrogeology and groundwater flow for the assessment of groundwater in the Zahrez Basin, Algeria. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOLAW)—Managing Systems at Risk; Earthscan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of Food and Agriculture 2016: Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/sofa/2016/en/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Barick, K.C.; Ratha, D. (Eds.) Magnetic Nanoparticles: Surface Engineering and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, A.; Sunil Kumar, K.; Thejaswi, A. Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation: A case study from Bandalamottu lead mining area, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, South India. Appl. Water Sci. 2014, 4, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, J.A.; Perumal, K.; Muthuramalingam, S. Evaluation of Groundwater Quality and Suitability for Irrigation Using Hydro-Chemical Process in Bhavani Taluk; Erode District: Tamilnadu, India, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, M.; Rajmohan, N.; Basahi, J.; Schneider, M.; Niyazi, B.; Alqarawy, A. Integrated hydrogeochemical groundwater flow path modelling in an arid environment. Water 2022, 14, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjab, R.; Khammar, H.; Redjaimia, L.; Merzoug, D.; Saheb, M. Impact of anthropic pressure on the quality and diversity of groundwater in the region of Sighus Oum-El-Bouaghi and El Rahmounia, Algeria. J. Bioresour. Manag. 2020, 7, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammar, H.; Hadjab, R.; Redjaimia, L.; Merzoug, D.; Saheb, M. Biodiversity and distribution of groundwater fauna in the Oum-El-Bouaghi region (Northeast of Algeria). Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2019, 20, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouakkaz, R.; Bouzidi, A.; Bouhoun, M. Hydrogeochemical characterization and groundwater quality assessment in the Bougaa area, Northeastern Algeria. Acta Geochim. 2021, 40, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redjaimia, L.; Hadjab, R.; Khammar, H.; Merzoug, D.; Saheb, M. Groundwater quality in two semi-arid areas of Algeria: Impact of water pollution on biodiversity. J. Bioresour. Manag. 2020, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satour, M.; Bouzidi, A.; Bouakkaz, R. Hydrogeochemical and isotopic assessment for characterizing groundwater quality in the Mitidja plain (northern Algeria). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 15000–15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagui, F.; Laamari, M.; Tahar-Chaouche, S.; Merzoug, D. Aphids and their parasitoid Hymenoptera in Oum El Bouaghi Province (Algeria). Bull. De La Soc. Zool. De Fr. 2023, 148, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rahal, O.; Gouaidia, L.; Garrote, L.; Sappa, G.; Balacco, G.; Brahmi, S.; de Filippi, F.M. Assessing the Impact of Climate Variability and Human Activity on Groundwater Resources in the Meskiana Plain, Northeast Algeria. Water Resour. 2024, 51, 1042–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminot, A.; Kérouel, R. Dosage Automatique Des Nutriments Dans Les Eaux Marines: Méthodes En Flux Continu; Éditions Quae: Versailles Cedex, France, 2007; ISBN 978-2-7592-0023-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rodier, J.; Legube, B.; Merlet, N. L’analyse de l’eau: Eaux Naturelles, Eaux Résiduaires, Eau De Mer, 9th ed.; Dunod: Malakoff Cedex, France, 2009; ISBN 978-2-10-007246-0. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, A.M. A graphic procedure in the geochemical interpretation of water-analyses. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union. 1944, 25, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdour, A.; Abdo, H.G.; Almohamad, H.; Alodah, A.; Al Dughairi, A.A.; Ghoneim, S.S.M.; Ali, E. Prediction of groundwater water quality index using classification techniques in arid environments. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, R.J. Mechanisms controlling world water chemistry. Science 1970, 170, 1088–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, N.J.; Shukla, U.K.; Ram, P. Hydrogeochemistry for the assessment of groundwater quality in Varanasi: A fast-urbanizing center in Uttar Pradesh, India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 173, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singaraja, C.; Chidambaram, S.; Anandhan, P.; Prasanna, M.V.; Thivya, C.; Thilagavathi, R.; Sarathidasan, J. Determination of the utility of groundwater with respect to the geochemical parameters: A case study from Tuticorin District of Tamil Nadu (India). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2014, 16, 689–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.K. An index number system for rating water quality. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1965, 37, 300–306. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.M.; McClelland, N.I.; Deininger, R.A.; Tozer, R.G. A water quality index—Do we dare. Water Sew. Work 1970, 117, 339–343. [Google Scholar]

- Poonam, T.; Tanushree, B.; Sukalyan, C. Water quality indices-important tools for water quality assessment: A review. Int. J. Adv. Chem. 2013, 1, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Meireles, A.C.M.; de Andrade, E.M.; Chaves, L.C.G.; Frischkorn, H.; Crisóstomo, L.A. A new proposal of the classification of irrigation water. Rev. Ciência Agronômica 2010, 41, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadjai, S.; Khammar, H.; Boulabeiz, M.; Nabed, A.N.; Benaabidate, L. Sensitivity Analysis and GIS Tools for Groundwater Vulnerability Assessment: Application in the Middle Chellif Plain, Algeria. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2024, 28, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.S.; Samadianfard, S.; Al-Ansari, N. Groundwater quality assessment for sustainable drinking and irrigation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maman Hassan, A.; Firat Ersoy, A. Statistical assessment of seasonal variation of groundwater quality in Çarşamba coastal plain, Samsun (Turkey). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, W.P. Permissible composition and concentration of irrigation waters. Proc. ASCE 1940, 66, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doneen, L.D. The influence of crop and soil on percolating water. In Proceedings of the Biennial Conference on Groundwater Recharge; Ground Water Recharge Laboratory, Southwest Branch, Soil and Water Conservation Research Division: Fresno, CA, USA, 1962; pp. 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, D.K. Groundwater Hydrology, 2nd ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA; Chichester, UK; Brisbane, Australia; Toronto, NO, Canada, 1981; pp. xiii + 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.K.; Gupta, I.C. Management of Saline Soils and Waters; Oxford and IBH Publishing Co.: New Delhi, India, 1987; p. 339. [Google Scholar]

- Raghunath, I.I.M. Groundwater, 2nd ed.; Wiley Eastern Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 1987; pp. 344–369. [Google Scholar]

- Subba Rao, N. Geochemistry and quality of groundwater of Gummanampadu sub-basin, Guntur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 67, 1451–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao, N. Groundwater quality from a part of Prakasam District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, D. A two-dimensional interpolation function for irregularly-spaced data. In Proceedings of the 1968 23rd ACM National Conference; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1968; pp. 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charizopoulos, N.; Zagana, E.; Psilovikos, A. Assessment of natural and anthropogenic impacts in groundwater, utilizing multivariate statistical analysis and inverse distance weighted interpolation modeling: The case of a Scopia basin (Central Greece). Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cao, J.; Lin, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Song, Y. Optimized inverse distance weighted interpolation algorithm for γ radiation field reconstruction. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeban, H. Comparison and evaluation of GIS-based spatial interpolation methods for estimation groundwater level in AL-Salman District—Southwest Iraq. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2018, 10, 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, K.H.; Gelete, T.B.; Iguala, A.D.; Kebede, E. Optimal interpolation approach for groundwater depth estimation. MethodsX 2024, 13, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadollah, S.B.H.; Sharafati, A.; Yaseen, Z.M. River water quality index prediction and uncertainty analysis: A comparative study of machine learning models. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grattan, S.R. Irrigation Water Salinity and Crop Production; ANR Publication 8066; University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources: Oakland, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Wang, H.; Fan, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, F. Crop yield and water productivity under salty water irrigation: A global meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 256, 107105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Batlles-delaFuente, A.; Fidelibus, M.D. Sustainable Irrigation in Agriculture: An Analysis of Global Research. Water 2019, 11, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukich, O.; Ben-Tahar, R.; Brahmi, M.; Alzain, M.N.; Noman, O.; Shahat, A.A.; Smiri, Y. Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation using a new customized irrigation water quality index. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolze, L.; Battistel, M.; Rolle, M. Oxidative dissolution of arsenic-bearing sulfide minerals in groundwater: Impact of hydrochemical and hydrodynamic conditions on arsenic release and surface evolution. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 5049–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, R.T.; DiGiulio, D.C. Geochemical impacts to groundwater from geologic carbon sequestration: Controls on pH and inorganic carbon concentrations from reaction path and kinetic modeling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4821–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mashreki, M.H.; Eid, M.H.; Saeed, O.; Székács, A.; Szűcs, P.; Gad, M.; Abukhadra, M.R.; AlHammadi, A.A.; Alrakhami, M.S.; Alshabibi, M.A.; et al. Integration of Geochemical Modeling, Multivariate Analysis, and Irrigation Indices for Assessing Groundwater Quality in the Al-Jawf Basin, Yemen. Water 2023, 15, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Ding, Z.; Li, H.; Li, X. Characterizing ecosystem water-use efficiency of croplands with eddy covariance measurements and MODIS products. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 85, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darkwah-Owusu, V.; Yusof, M.A.M.; Sokama-Neuyam, Y.A.; Turkson, J.N.; Fjelde, I. A comprehensive review of remediation strategies for mitigating salt precipitation and enhancing CO2 injectivity during CO2 injection into saline aquifers. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 950, 175232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S. Quantitative regression analysis of total hardness related physicochemical parameters of groundwater. Open Access J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 2, 000160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao, N. Controlling Factors of Fluoride in Groundwater in a Part of South India. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwule, R.O.; Simeon, K.A.; Amer, M.A. Coupling hydrochemical characterization with geospatial analysis to understand groundwater quality parameters in North Central Nigeria. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2023, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N.; Qian, H.; Li, P. Entropy water quality index and probabilistic health risk assessment from geochemistry of groundwaters in hard rock terrain of Nanganur County, South India. Chemosphere Earth Rep. 2020, 1, 125544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adimalla, N. Spatial distribution, exposure, and potential health risk assessment from nitrate in drinking water from semi-arid region of South India. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2019, 29, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba Rao, N.; Das, R.; Gugulothu, S. Understanding the factors contributing to groundwater salinity in the coastal region of Andhra Pradesh, India. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2022, 250, 104053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derdour, A.; Mahamat Ali, M.M.; Chabane Sari, S.M. Evaluation of the quality of groundwater for its appropriateness for drinking purposes in the watershed of Naama, SW of Algeria, by using water quality index (WQI). SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, Q.; Peng, W.; Liu, X. Source apportionment and natural background levels of major ions in shallow groundwater using multivariate statistical method: A case study in Huaibei Plain, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentekhici, N.; Benkesmia, Y.; Bouhlala, M.A.; Saad, A.; Ghabi, M. Mapping and assessment of groundwater pollution risks in the main aquifer of the Mostaganem plateau (Northwest Algeria): Utilizing the novel vulnerability index and decision tree model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 45074–45104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroubo, L.A.; Moreira-Silva, M.R.; Teixeira, J.J.; Teixeira, M.F. Influence of Rainfall Seasonality in Groundwater Chemistry at Western Region of São Paulo State Brazil. Water 2021, 13, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, R.A.; Naser, R.S.; El-Bakkali, M.; Othman, M.D.M.; Yahya, M.S.; Raweh, S.; Mohammed, A.; Belghyti, D. Groundwater quality deterioration evaluation for irrigation using several indices and geographic information systems: A case study. Desalination Water Treat. 2024, 320, 100645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Haj, R.; Merheb, M.; Halwani, J.; Ouddane, B. Baseline hydro-geochemical characteristics of groundwater in Abu Ali watershed (Northern Lebanon). J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.H.; Elbagory, M.; Tamma, A.A.; Gad, M.; Elsayed, S.; Hussein, H.; Péter, S. Evaluation of groundwater quality for irrigation in deep aquifers using multiple graphical and indexing approaches supported with machine learning models and GIS techniques, Souf Valley, Algeria. Water 2023, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Osta, M.; Masoud, M.; Alqarawy, A.; Elsayed, S.; Gad, M. Groundwater suitability for drinking and irrigation using water quality indices and multivariate modeling in Makkah Al-Mukarramah province, Saudi Arabia. Water 2022, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Hammou, B.; Chabour, N.; Belksier, M. Assessment of groundwater quality for irrigation in arid regions: Case study of the Ksour Mountains, Algeria. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 1963, 13065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerroudj, A. Weather Parameter Trends and Variability of the Water Balance in Constantine State, Algeria. Arab World Geogr. 2023, 26, 301–315. [Google Scholar]

| qi (%) | EC (µS·cm−1) | SAR | (meq·L−1) | Na+ (meq·L−1) | Cl− (meq·L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85–100 | 20,000 ≤ EC < 750,000 | 2 ≤ SAR < 3 | 1 ≤ HCO3− < 1.5 | 2 ≤ Na+ < 3 | 1 ≤ Cl− < 4 |

| 60–85 | 750,000 ≤ EC < 150,000 | 3 ≤ SAR < 6 | 1.5 ≤ HCO3− < 4.5 | 3 ≤ Na+ < 6 | 4 ≤ Cl− < 7 |

| 35–60 | 150,000 ≤ EC < 300,000 | 6 ≤ SAR < 12 | 4.5 ≤ HCO3− < 8.5 | 6 ≤ Na+ < 9 | 7 ≤ Cl− < 10 |

| 0–35 | EC < 20,000 or ≥300,000 | SAR < 2 or ≥12 | HCO3− < 1 or ≥8.5 | Na+ < 2 or ≥9 | Cl− < 1 or ≥ 10 |

| Parameters | WQS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 4 | 0.09756098 | 7.5 |

| TH | 4 | 0.09756098 | |

| EC (25 °C) | 4 | 0.09756098 | 500 |

| 1 | 0.02439024 | 10 | |

| 1 | 0.02439024 | 300 | |

| 2 | 0.04878049 | 75 | |

| 2 | 0.04878049 | 30 | |

| 4 | 0.09756098 | 200 | |

| 5 | 0.12195122 | 150 | |

| 5 | 0.12195122 | 250 | |

| 5 | 0.12195122 | 45 | |

| TDS | 4 | 0.09756098 | 500 |

| 41 | 1 |

| Type Classes | C 1 | C 2 | C 3 | C 4 | C 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range of (IWQI) for irrigation purposes | <40 | 40–55 | 55–70 | 70–85 | 85–100 |

| Categories | Severe Restriction | High Restriction | Moderate Restriction | Low Restriction | No Restriction |

| Classification Pattern | Equation | Range | Categories | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity (EC) | / | <250 | Excellent | ||

| 250–750 | Good | ||||

| 750–2250 | Permissible Doubtful | [10] | |||

| 2250–5000 | Unacceptable | ||||

| >5000 | |||||

| Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) | (3) | <2 | Excellent | [9] | |

| 2–12 | Good | ||||

| 12–22 | Permissible | ||||

| 22–32 | Fair | ||||

| >32 | Poor | ||||

| Residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC) | (4) | <1.25 | Permissible | [12] | |

| ≥1.25 | Unsuitable | ||||

| Kelley’s ratio (KR) | (5) | >1 | Unsuitable | [51] | |

| <1 | Suitable | ||||

| Permeability index (PI) | (6) | <25.0 | Unsuitable | ||

| 25–75 | Good | ||||

| >75 | Suitable | [11,52] | |||

| Potential Salinity (PS) | (7) | <3 | Excellent | ||

| 3–5 | Good | ||||

| >5 | Unsuitable | ||||

| Percent sodium (Na%) | (8) | 0–20 | Excellent | [10] | |

| 20–40 | Good | ||||

| 40–60 | permissible | ||||

| 60–80 | doubtful | ||||

| >80 | Unacceptable | ||||

| Soluble sodium Percentage (SSP) | (9) | <50 | Good | [53] | |

| >50 | Unsuitable | ||||

| The Residual Sodium Bicarbonate (RSBC) | [54] | ||||

| Magnesium Hazard Ratio (MHR) | (10) | <50 | Good | [55] | |

| >50 | Unsuitable | ||||

| < 1.0 | Insignificant pollution |

| 1.0 < < 1.5 | Low pollution |

| 1.5 < < 2.0 | Moderate pollution |

| 2.0 < < 2.5 | High pollution |

| > 2.5 | Very high pollution |

| Parameters | T °C | EC 25 °C | TDS | pH | Cl− | Na+ | K+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | TH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dry | WHO | 500 | 500 | 8.5 | 250 | 250 | 200 | 50 | 200 | 12 | 75 | 45 | 300 | |

| W 01 | 11.80 | 2053.67 | 2053.33 | 6.96 | 352.73 | 242.58 | 150.51 | 1.29 | 233.88 | 4.73 | 48.36 | 80.00 | 35.00 | |

| W 02 | 11.93 | 939.00 | 939.00 | 7.42 | 288.52 | 106.50 | 166.78 | 2.20 | 34.04 | 13.52 | 21.88 | 100.00 | 43.00 | |

| W 03 | 11.93 | 866.33 | 866.00 | 7.34 | 162.39 | 98.75 | 119.83 | 2.26 | 62.76 | 3.06 | 30.00 | 66.31 | 28.50 | |

| W 04 | 10.93 | 3929.00 | 3929.33 | 7.98 | 469.41 | 377.50 | 264.41 | 3.09 | 349.69 | 3.73 | 59.40 | 99.00 | 42.60 | |

| W 05 | 9.20 | 4092.00 | 4092.00 | 7.76 | 499.63 | 248.50 | 244.07 | 6.09 | 244.66 | 17.81 | 49.27 | 103.00 | 44.30 | |

| W 06 | 11.93 | 4220.33 | 4220.33 | 7.61 | 388.35 | 337.25 | 388.39 | 1.77 | 273.80 | 12.64 | 75.93 | 112.00 | 48.00 | |

| W 07 | 12.87 | 1408.67 | 1408.67 | 7.58 | 146.72 | 153.83 | 146.44 | 4.81 | 124.19 | 7.10 | 17.82 | 60.00 | 26.00 | |

| W 08 | 11.80 | 1522.33 | 1522.33 | 7.24 | 249.32 | 222.42 | 188.10 | 3.99 | 234.75 | 4.73 | 44.20 | 61.00 | 26.50 | |

| W 09 | 9.07 | 527.67 | 527.33 | 7.48 | 98.59 | 106.92 | 122.03 | 3.11 | 38.34 | 4.75 | 27.97 | 55.00 | 24.20 | |

| W 10 | 16.20 | 1304.33 | 1304.33 | 7.30 | 193.99 | 165.67 | 187.12 | 1.19 | 122.43 | 1.57 | 28.98 | 81.00 | 34.50 | |

| W 11 | 12.53 | 2314.00 | 2314.00 | 7.43 | 317.87 | 153.83 | 268.47 | 2.08 | 122.43 | 6.08 | 43.47 | 88.00 | 38.00 | |

| W 12 | 11.37 | 2040.67 | 2040.67 | 7.43 | 452.74 | 195.25 | 235.93 | 1.84 | 201.01 | 9.28 | 31.16 | 98.00 | 42.00 | |

| W 13 | 12.20 | 3536.67 | 3537.00 | 7.45 | 487.39 | 307.67 | 337.63 | 2.48 | 311.02 | 3.08 | 44.20 | 110.00 | 47.00 | |

| W 14 | 11.80 | 2105.67 | 2104.67 | 7.21 | 250.30 | 189.33 | 231.86 | 2.76 | 176.15 | 4.45 | 28.98 | 84.33 | 36.00 | |

| W 15 | 10.80 | 863.67 | 863.67 | 7.31 | 280.40 | 102.83 | 174.91 | 8.11 | 99.97 | 3.92 | 26.95 | 80.71 | 36.00 | |

| W 16 | 10.33 | 1203.33 | 1203.67 | 7.41 | 236.92 | 201.58 | 178.98 | 8.05 | 198.31 | 4.00 | 26.95 | 74.11 | 32.00 | |

| W 17 | 10.67 | 1139.00 | 1139.00 | 7.20 | 228.45 | 153.83 | 162.71 | 12.71 | 82.14 | 1.65 | 54.34 | 94.91 | 41.00 | |

| W 18 | 11.67 | 992.00 | 991.67 | 7.39 | 108.61 | 171.58 | 219.66 | 11.96 | 39.12 | 1.74 | 58.40 | 62.00 | 27.00 | |

| W 19 | 9.60 | 3760.00 | 3759.67 | 7.30 | 498.34 | 501.67 | 338.81 | 1.77 | 454.37 | 10.10 | 59.85 | 110.31 | 48.00 | |

| W 20 | 11.53 | 1885.00 | 1885.00 | 7.27 | 317.49 | 183.42 | 203.39 | 3.83 | 95.44 | 3.08 | 59.41 | 116.51 | 49.50 | |

| W 21 | 13.27 | 1522.67 | 1522.67 | 7.04 | 216.51 | 165.67 | 191.19 | 10.14 | 110.11 | 11.01 | 30.00 | 56.11 | 25.00 | |

| W 22 | 13.47 | 1247.67 | 1248.00 | 5.31 | 196.20 | 189.33 | 320.68 | 3.30 | 134.36 | 12.06 | 13.77 | 81.31 | 36.00 | |

| W 23 | 14.73 | 915.33 | 915.00 | 7.57 | 225.08 | 177.50 | 138.30 | 13.19 | 28.95 | 3.40 | 37.10 | 111.00 | 48.40 | |

| MIN | 9.07 | 527.67 | 527.33 | 5.31 | 98.59 | 98.75 | 119.83 | 1.19 | 28.95 | 1.57 | 13.77 | 55.00 | 24.20 | |

| MAX | 16.20 | 4220.33 | 4220.33 | 7.98 | 499.63 | 501.67 | 388.39 | 13.19 | 454.37 | 17.81 | 75.93 | 116.51 | 49.50 | |

| MOY | 11.81 | 1929.96 | 1929.88 | 7.30 | 289.82 | 206.67 | 216.53 | 4.87 | 164.00 | 6.41 | 39.93 | 86.29 | 37.33 | |

| SD | 1.64 | 1163.80 | 1163.80 | 0.48 | 125.05 | 96.36 | 74.17 | 3.86 | 111.32 | 4.4 | 16.1 | 19.83 | 8.36 | |

| wet | W 01 | 12.73 | 2650.67 | 2650.67 | 7.99 | 498.10 | 207.08 | 207.46 | 6.33 | 213.00 | 4.52 | 52.31 | 106.00 | 46.00 |

| W 02 | 12.33 | 1042.00 | 1042.33 | 7.13 | 442.84 | 118.33 | 280.68 | 3.01 | 52.22 | 15.55 | 34.05 | 133.00 | 56.60 | |

| W 03 | 10.73 | 877.67 | 878.33 | 8.12 | 193.03 | 112.42 | 178.98 | 4.00 | 60.04 | 1.91 | 22.90 | 75.31 | 32.00 | |

| W 04 | 9.60 | 3983.33 | 3984.33 | 7.73 | 534.38 | 313.00 | 305.08 | 2.16 | 322.08 | 3.40 | 54.05 | 150.00 | 64.00 | |

| W 05 | 8.60 | 4083.67 | 4083.67 | 7.51 | 382.29 | 556.17 | 370.17 | 7.00 | 502.42 | 15.44 | 49.00 | 132.00 | 56.20 | |

| W 06 | 12.53 | 5001.67 | 5001.67 | 7.86 | 493.47 | 566.25 | 337.63 | 0.91 | 414.22 | 14.29 | 62.64 | 182.00 | 77.00 | |

| W 07 | 13.40 | 1437.67 | 1437.33 | 7.87 | 317.50 | 159.75 | 235.93 | 4.56 | 182.47 | 7.81 | 33.04 | 63.00 | 27.00 | |

| W 08 | 11.20 | 1387.39 | 1387.04 | 7.56 | 274.94 | 153.83 | 174.91 | 3.71 | 160.17 | 2.51 | 40.72 | 69.00 | 30.00 | |

| W 09 | 14.67 | 603.00 | 603.33 | 7.88 | 101.58 | 112.42 | 166.78 | 2.32 | 36.19 | 2.64 | 20.87 | 63.00 | 27.00 | |

| W 10 | 16.73 | 1213.33 | 1213.33 | 7.80 | 232.00 | 133.00 | 222.34 | 4.32 | 124.27 | 1.05 | 30.00 | 88.00 | 37.30 | |

| W 11 | 13.80 | 2136.00 | 2136.00 | 7.95 | 316.56 | 202.00 | 352.83 | 5.20 | 153.67 | 4.21 | 50.00 | 142.00 | 61.00 | |

| W 12 | 11.27 | 3145.67 | 3145.33 | 7.91 | 464.96 | 308.75 | 366.07 | 2.21 | 211.51 | 9.28 | 58.79 | 148.00 | 62.60 | |

| W 13 | 12.87 | 3508.33 | 3508.00 | 7.97 | 580.06 | 298.00 | 341.69 | 1.97 | 349.35 | 0.93 | 49.27 | 122.00 | 52.00 | |

| W 14 | 11.73 | 1661.33 | 1661.67 | 7.91 | 308.54 | 189.75 | 235.93 | 1.27 | 222.76 | 3.19 | 31.07 | 88.33 | 37.60 | |

| W 15 | 11.53 | 1240.00 | 1240.33 | 7.87 | 216.71 | 99.00 | 227.80 | 4.99 | 82.51 | 4.18 | 22.00 | 89.71 | 38.00 | |

| W 16 | 12.73 | 973.67 | 974.00 | 7.54 | 298.62 | 106.50 | 178.98 | 5.36 | 158.81 | 4.26 | 22.90 | 74.11 | 32.00 | |

| W 17 | 10.83 | 1054.67 | 1054.67 | 7.83 | 336.36 | 136.08 | 146.44 | 9.94 | 96.03 | 0.99 | 39.13 | 94.91 | 41.00 | |

| W 18 | 11.93 | 748.00 | 748.00 | 8.17 | 99.62 | 99.67 | 206.34 | 9.03 | 49.48 | 1.50 | 22.90 | 62.00 | 27.00 | |

| W 19 | 9.63 | 4529.12 | 4529.12 | 7.89 | 501.39 | 577.58 | 337.63 | 2.61 | 488.29 | 8.62 | 42.31 | 147.31 | 63.00 | |

| W 20 | 12.83 | 1848.67 | 1848.33 | 7.65 | 422.01 | 153.83 | 211.52 | 3.00 | 95.64 | 2.06 | 48.26 | 116.51 | 50.00 | |

| W 21 | 13.63 | 1170.67 | 1183.33 | 7.87 | 266.15 | 101.00 | 203.39 | 7.00 | 111.10 | 12.43 | 17.11 | 56.11 | 26.00 | |

| W 22 | 15.07 | 1315.33 | 1315.33 | 3.78 | 299.76 | 188.58 | 322.07 | 2.29 | 161.22 | 9.12 | 23.97 | 81.31 | 36.00 | |

| W 23 | 15.67 | 1089.33 | 1089.67 | 7.92 | 283.03 | 112.42 | 219.66 | 10.18 | 49.09 | 1.91 | 30.00 | 120.00 | 52.20 | |

| MIN | 8.6 | 603 | 603.33 | 3.77 | 99.62 | 99 | 146.44 | 0.90 | 36.18 | 0.92 | 17.11 | 56.11 | 26 | |

| MAX | 16.7 | 5001.67 | 5001.67 | 8.16 | 580.05 | 577.58 | 370.16 | 10.18 | 502.42 | 15.54 | 62.63 | 182 | 77 | |

| MOY | 12.4 | 2000.49 | 2031.12 | 7.63 | 341.90 | 217.62 | 253.49 | 4.40 | 186.80 | 5.72 | 37.27 | 104.50 | 44.84 | |

| SD | 1.97 | 1359.94 | 1336.90 | 0.87 | 132.46 | 152.83 | 72.12 | 2.68 | 138.91 | 4.831 | 13.64 | 35.34 | 14.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Messaid, N.; Hadjab, R.; Khammar, H.; Hadjab, A.; Bouchema, N.; Chebout, A.; Aqnouy, M.; Tzoraki, O.; Benaabidate, L. Assessment of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation in the Semi-Arid Region of Oum El Bouaghi (Northeastern Algeria) Using Groundwater Quality and Pollution Indices and GIS Techniques. Water 2025, 17, 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223266

Messaid N, Hadjab R, Khammar H, Hadjab A, Bouchema N, Chebout A, Aqnouy M, Tzoraki O, Benaabidate L. Assessment of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation in the Semi-Arid Region of Oum El Bouaghi (Northeastern Algeria) Using Groundwater Quality and Pollution Indices and GIS Techniques. Water. 2025; 17(22):3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223266

Chicago/Turabian StyleMessaid, Norelhouda, Ramzi Hadjab, Hichem Khammar, Aymen Hadjab, Nadhir Bouchema, Abderrezzeq Chebout, Mourad Aqnouy, Ourania Tzoraki, and Lahcen Benaabidate. 2025. "Assessment of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation in the Semi-Arid Region of Oum El Bouaghi (Northeastern Algeria) Using Groundwater Quality and Pollution Indices and GIS Techniques" Water 17, no. 22: 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223266

APA StyleMessaid, N., Hadjab, R., Khammar, H., Hadjab, A., Bouchema, N., Chebout, A., Aqnouy, M., Tzoraki, O., & Benaabidate, L. (2025). Assessment of Groundwater Quality for Irrigation in the Semi-Arid Region of Oum El Bouaghi (Northeastern Algeria) Using Groundwater Quality and Pollution Indices and GIS Techniques. Water, 17(22), 3266. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223266