Spatial Structure and Temporal Dynamics in Clear Lake, CA: The Role of Wind in Promoting and Sustaining Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lakewide Sensing by Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV)

2.2. Discrete Water Sample Collections and Water Column Profiling from Boats

2.3. Vertical Profiling Using a Wirewalker

3. Results

3.1. Lakewide Observations 2020

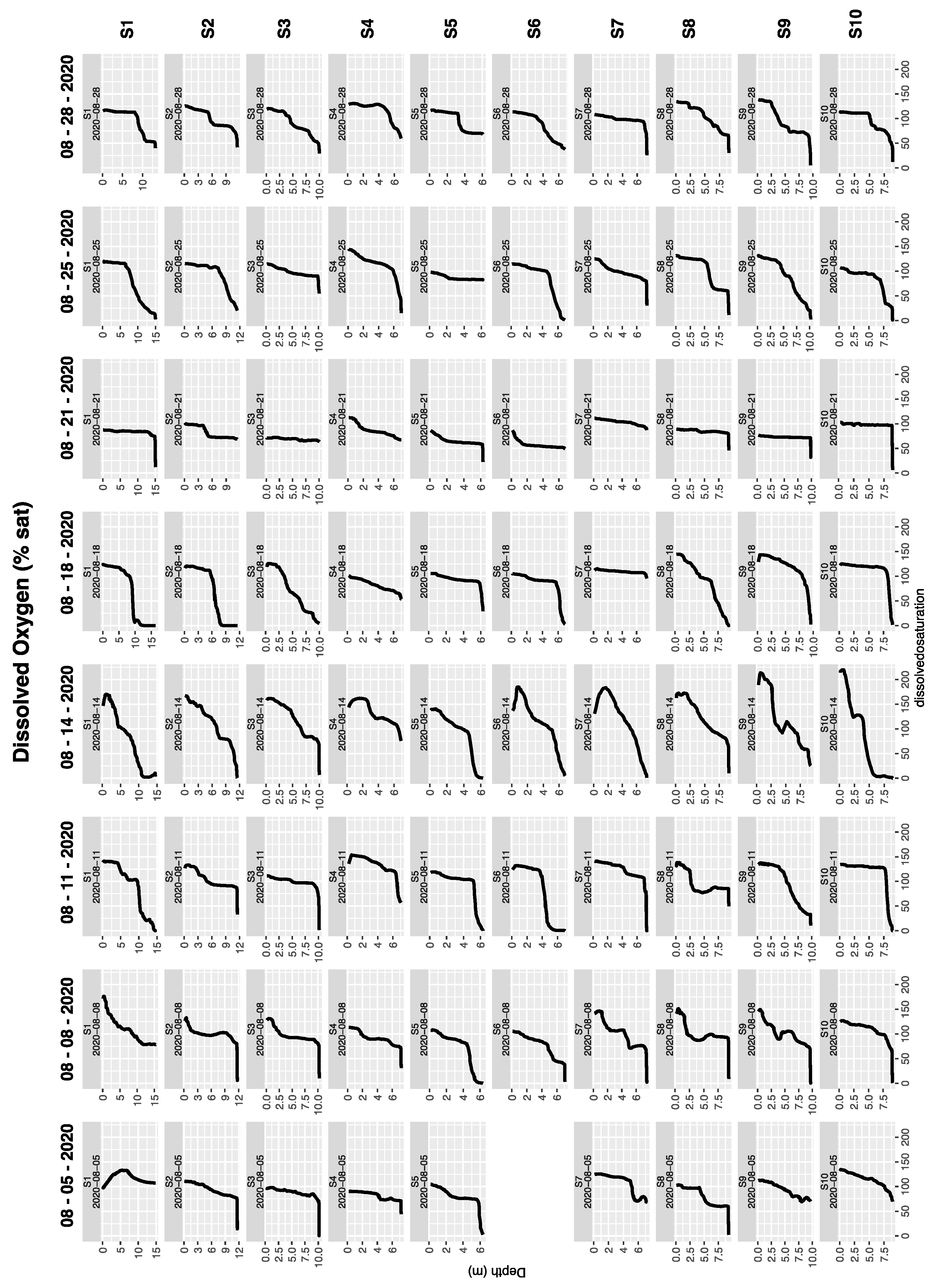

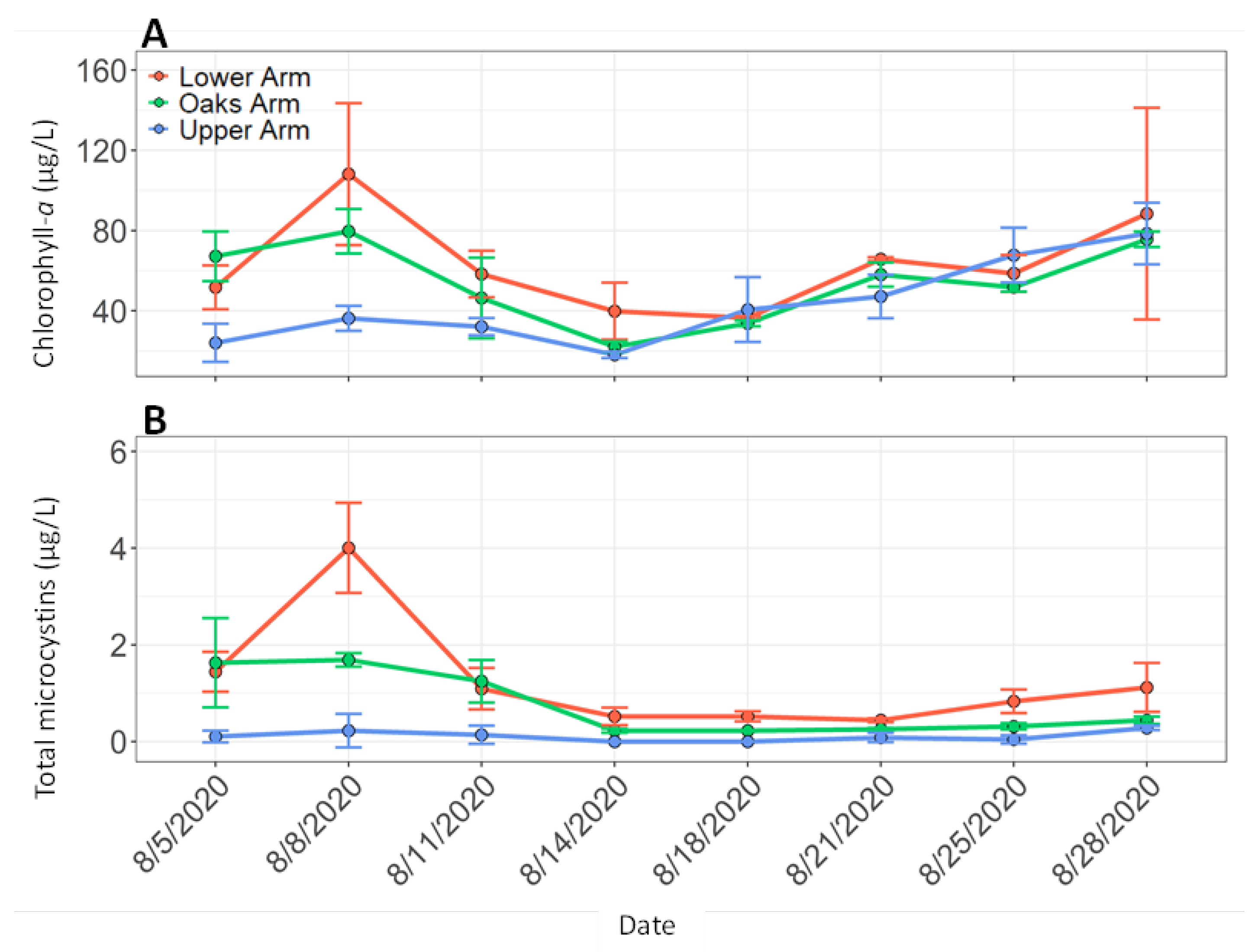

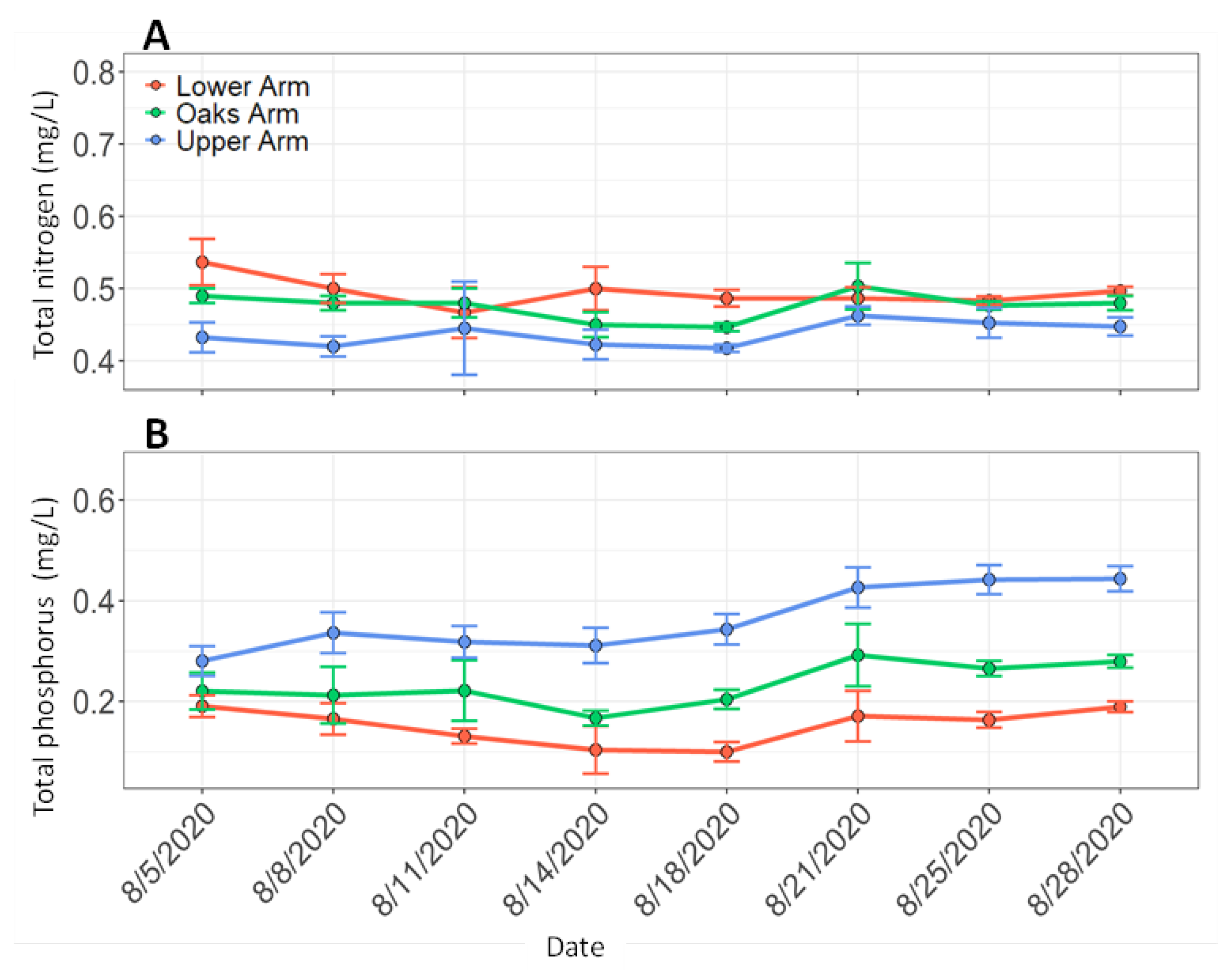

3.2. Discrete Water Samples and Vertical Profiles During Boat Surveys

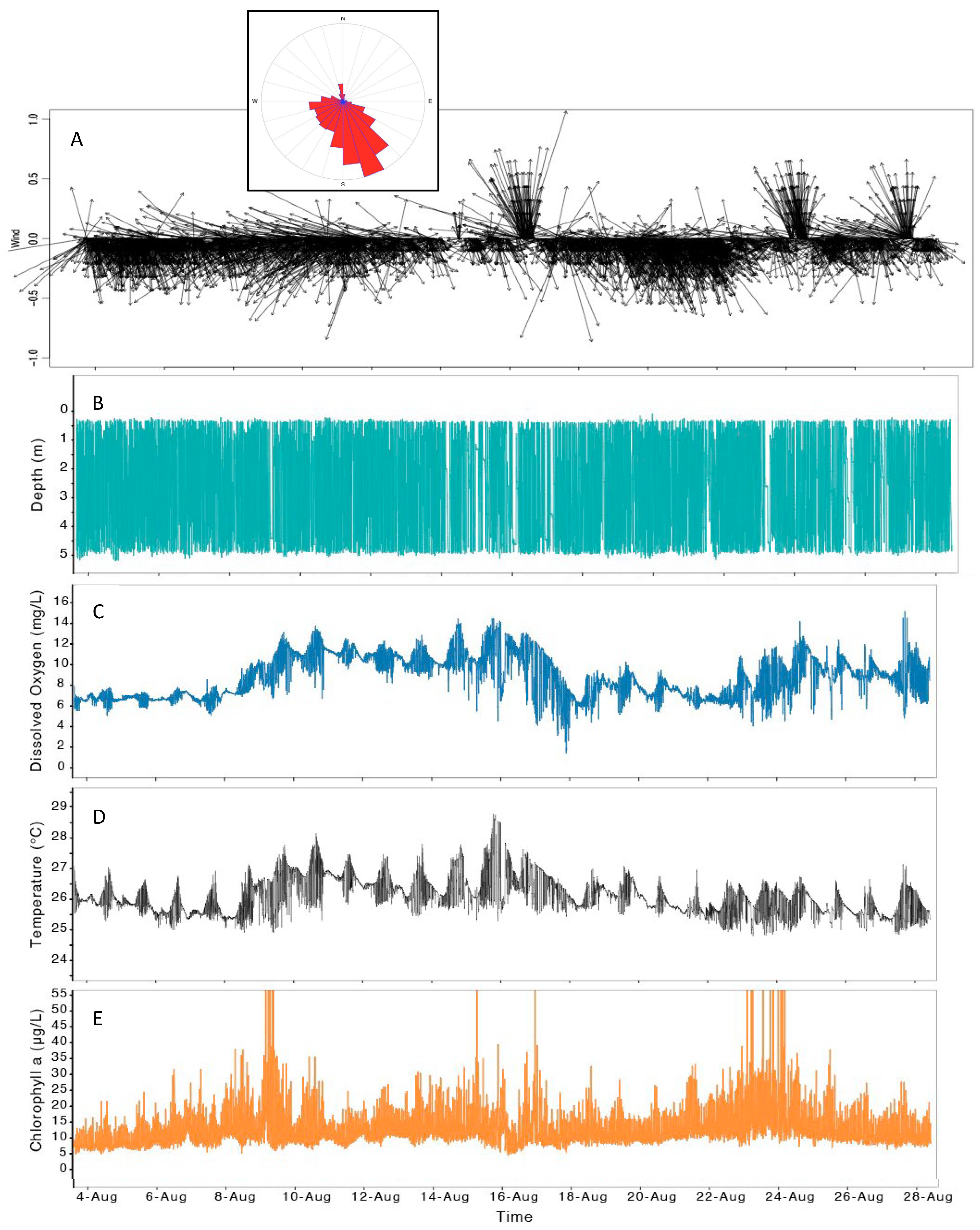

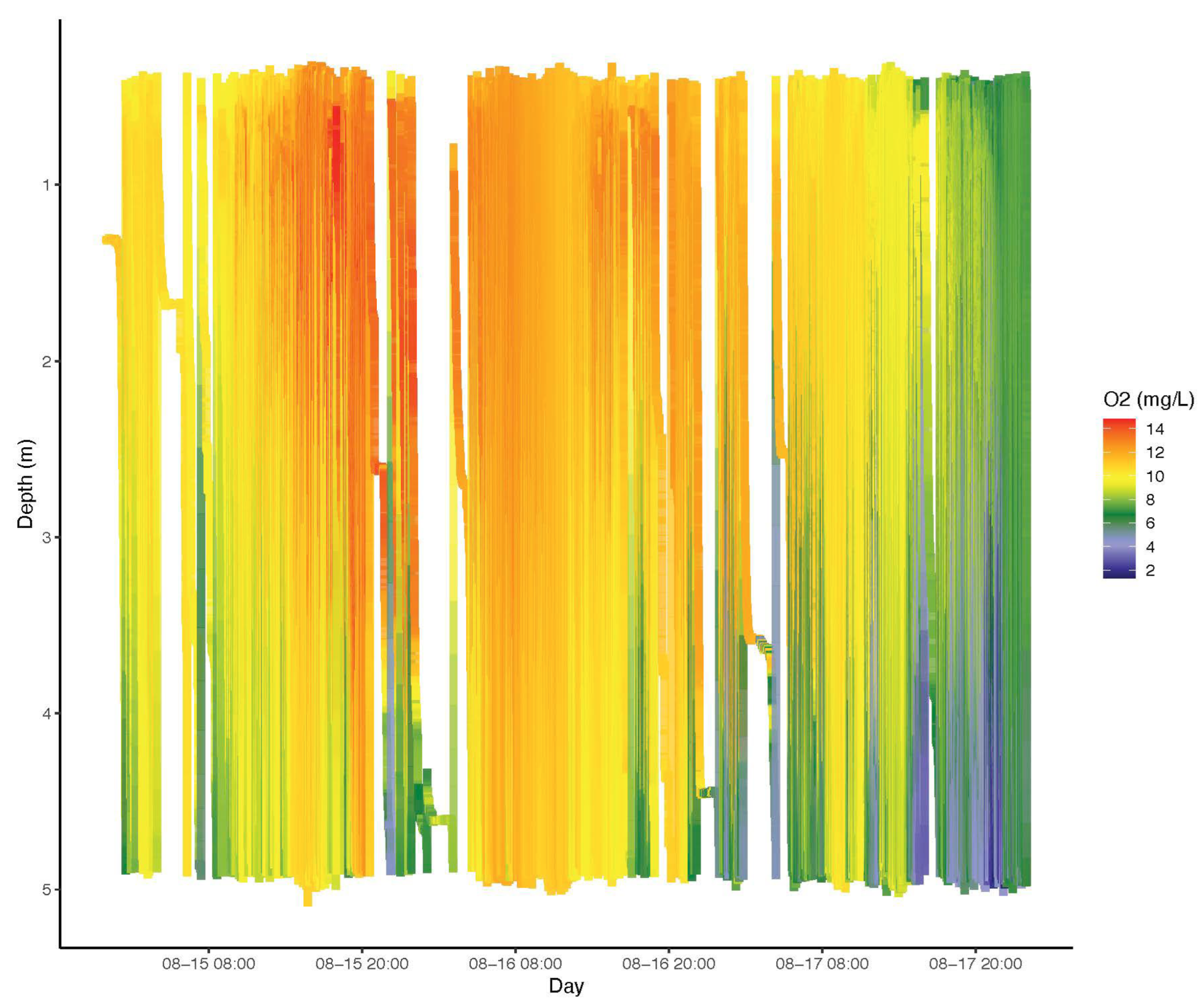

3.3. Water Column Structure Evolved Rapidly at a Mid-Lake Station

4. Discussion

4.1. Complementary Information for Lakewide Assessment from AUV Missions and Boat Surveys

4.2. High-Resolution Sensing Provided Unprecedented Insight into Water Column Dynamics

4.3. Multiple Roles of Wind as a Factor Affecting cHABs in Clear Lake

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bradbury, J.P. Diatom Biostratigraphy and the Paleolimnology of Clear Lake, Lake County, California. Late Quaternary Climate, Tectonism, Sedimentation in Clear Lake, Northern California Coasts; Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 1988; pp. 97–129. [Google Scholar]

- Richerson, P.J.; Suchanek, T.H.; Zierenberg, R.A.; Osleger, D.A.; Heyvaert, A.C.; Slotton, D.G.; Eagles-Smith, C.A.; Vaughn, C.E. Anthropogenic stressors and changes in the clear lake ecosystem as recorded in sediment cores. Ecol. Appl. 2008, 18, A257–A283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richerson, P.J.; Suchanek, T.H.; Why, S.J. The Causes and Control of Algal Blooms in Clear Lake, in Clean Lake Diagnostic/Feasibility Study for Clear Lake, California; University of California at Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 1994; p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Borrelli, J.J.; Relyea, R.A. A review of spatial structure of freshwater food webs: Issues and opportunities modeling within-lake meta-ecosystems. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2022, 67, 1746–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, I.; Stewart Brittany, P.; Florea Kyra, M.; Smith, J.; Webb Eric, A.; Caron David, A. Temporal and spatial dynamics of harmful algal bloom-associated microbial communities in eutrophic Clear Lake, California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e00011-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, C.R.; Wetzel, R.G. A study of the primary productivity of Clear Lake, Lake County California. Ecology 1963, 44, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrigley, R.C.; Horne, A.J. Remote sensing and lake eutrophication. Nature 1974, 250, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Eggleston, E.; Howard, M.D.A.; Ryan, S.; Gichuki, J.; Kennedy, K.; Tyler, A.; Beck, M.; Huie, S.; Caron, D.A. Historic and recent trends of cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms and environmental conditions in Clear Lake, California: A 70-year perspective. Elementa 2023, 11, 00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, G.M.; Stanton, B.; Ryan, S.; Little, A.; Carpenter, C.; Paulukonis, S. Notes from the field: Harmful Algal Bloom affecting private drinking water intakes—Clear Lake, California, June–November 2021. MMWR 2022, 71, 1306–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, B.; Little, A.; Miller, L.; Solomon, G.; Ryan, S.; Paulukonis, S.; Cajina, S. Microcystins at the tap: A closer look at unregulated drinking water contaminants. Water Sci. 2023, 5, e1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioni, C.E.; Kudela, R. Harmful cyanobacteria blooms and their toxins in Clear Lake and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (California). Delta 2011, 10, 058–150. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, M.M.; Cortes, A.; Forrest, A.L.; Framsted, N.; Sadro, S.; Schladow, S.G.; De Palma-Dow, A. Internal phosphorus loading alters nutrient limitation and contributes to cyanobacterial blooms in a polymictic lake. Aquat. Sci. 2024, 86, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, L. Amendment to the Water Quality Control Plan for the Sacramento River and San Joaquin River Basins for the Control of Nutrients in Clear Lake; Staff Report Rancho Cordova, CA; Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board: Rancho Cordova, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Palma-Dow, A.; McCullough, I.M.; Brentrup, J.A. Turning up the heat: Long-term water quality responses to wildfires and climate change in a hypereutrophic lake. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, L.F. Effect of wind on the distribution of chlorophyll a in Clear Lake, Iowa. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1963, 8, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, F.J.; Schladow, S.G. Dynamics of large polymictic Lake. II: Numerical simulations. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2003, 129, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, F.J.; Schladow, S.G.; Monismith, S.G.; Stacey, M.T. Dynamics of large polymictic lake. I: Field observations. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2003, 129, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, F.J.; Schladow, S.G.; Monismith, S.G.; Stacey, M.T. On the effects of topography on wind and the generation of currents in a large multi-basin lake. Hydrobiologia 2005, 532, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, P.; Terrill, E.; Otero, M.; Hazard, L.; Middleton, W. Mapping ocean outfall plumes and their mixing using autonomous underwater vehicles. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2012, 117, C07016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seegers, B.N.; Birch, J.M.; Marin, R.; Scholin, C.A.; Caron, D.A.; Seubert, E.L.; Howard, M.D.A.; Robertson, G.L.; Jones, B.H. Subsurface seeding of surface harmful algal blooms observed through the integration of autonomous gliders, moored environmental sample processors, and satellite remote sensing in southern California. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015, 60, 754–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kieft, B.; Hobson, B.W.; Ryan, J.P.; Barone, B.; Preston, C.M.; Roman, B.; Raanan, B.Y.; Marin, I.R.; O’Reilly, T.C.; et al. Autonomous tracking and sampling of the deep chlorophyll maximum layer in an open-ocean eddy by a long-range autonomous underwater vehicle. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 45, 1308–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brentrup, J.A.; Williamson, C.E.; Colom-Montero, W.; Eckert, W.; de Eyto, E.; Grossart, H.-P.; Huot, Y.; Isles, P.D.F.; Knoll, L.B.; Leach, T.H.; et al. The potential of high-frequency profiling to assess vertical and seasonal patterns of phytoplankton dynamics in lakes: An extension of the Plankton Ecology Group (PEG) model. Inland Waters 2016, 6, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcé, R.; George, G.; Buscarinu, P.; Deidda, M.; Dunalska, J.; de Eyto, E.; Flaim, G.; Grossart, H.-P.; Istvanovics, V.; Lenhardt, M.; et al. Automatic high frequency monitoring for improved lake and reservoir management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 10780–10794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaudo, C.; Odermatt, D.; Bouffard, D.; Rahaghi, A.I.; Lavanchy, S.; Wüest, A. The imprint of primary production on high-frequency profiles of lake optical properties. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 14234–14244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogora, M.; Cancellario, T.; Caroni, R.; Kamburska, L.; Manca, D.; Musazzi, S.; Tiberti, R.; Lami, A. High-frequency monitoring through in-situ fluorometric sensors: A supporting tool to long-term ecological research on lakes. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1058515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkel, R.; Goldin, M.A.; Smith, J.A.; Sun, O.M.; Aja, A.A.; Bui, M.N.; Hughen, T. The Wirewalker: A vertically profiling instrument carrier powered by ocean waves. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2011, 28, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, S.L.; Forrest, A.L.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Jin, Y.; Cortés, A.; Schladow, S.G. Quantifying scales of spatial variability of cyanobacteria in a large, eutrophic lake using multiplatform remote sensing tools. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 612934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, S.M.; Moline, M.A.; Schaffner, A.; Garrison, T.; Chang, G. Sub-kilometer length scales in coastal waters. Cont. Shelf Res. 2008, 28, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, P.D.; Tyler, A.N.; Willby, N.J.; Gilvear, D.J. The spatial dynamics of vertical migration by Microcystis aeruginosa in a eutrophic shallow lake: A case study using high spatial resolution time-series airborne remote sensing. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2008, 53, 2391–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.W.; Stumpf, R.; Bullerjahn, G.S.; McKay, R.M.L.; Chaffin, J.D.; Bridgeman, T.B.; Winslow, C. Science meets policy: A framework for determining impairment designation criteria for large waterbodies affected by cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms. Harmful Algae 2019, 81, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, R.P.; Davis, T.W.; Wynne, T.T.; Graham, J.L.; Loftin, K.A.; Johengen, T.H.; Gossiaux, D.; Palladino, D.; Burtner, A. Challenges for mapping cyanotoxin patterns from remote sensing of cyanobacteria. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, D.; Ackerman, J.D.; Boegman, L. Factors affecting the development and dynamics of hypoxia in a large shallow stratified lake: Hourly to seasonal patterns. Water Resour. Res. 2013, 49, 2380–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, C.H. The exchange of dissolved substances between mud and water in lakes. J. Ecol. 1941, 29, 280–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defeo, S.; Beutel, M.W.; Rodal-Morales, N.; Singer, M. Sediment release of nutrients and metals from two contrasting eutrophic California reservoirs under oxic, hypoxic and anoxic conditions. Front. Water 2024, 6, 1474057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.S.; Johengen, T.H.; Miller, R.; Godwin, C.M. Accelerated sediment phosphorus release in Lake Erie’s central basin during seasonal anoxia. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 3582–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, G.; Qin, B. Hypoxia and its environmental influences in large, shallow, and eutrophic Lake Taihu, China, 1922–2010. Verhandlungen Des Int. Ver. Limnol. 2008, 30, 361–365. [Google Scholar]

- Jane, S.F.; Hansen, G.J.A.; Kraemer, B.M.; Leavitt, P.R.; Mincer, J.L.; North, R.L.; Pilla, R.M.; Stetler, J.T.; Williamson, C.E.; Woolway, R.I.; et al. Widespread deoxygenation of temperate lakes. Nature 2021, 594, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosten, S.; Huszar, V.L.M.; Bécares, E.; Costa, L.S.; van Donk, E.; Hansson, L.-A.; Jeppesen, E.; Kruk, C.; Lacerot, G.; Mazzeo, N.; et al. Warmer climates boost cyanobacterial dominance in shallow lakes. Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzouki, E.; Lürling, M.; Fastner, J.; De Senerpont Domis, L.; Wilk-Woźniak, E.; Koreivienė, J.; Seelen, L.; Teurlincx, S.; Verstijnen, Y.; Krztoń, W.; et al. Temperature effects explain continental scale distribution of cyanobacterial toxins. Toxins 2018, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osgood, R.A. The Limnology, Ecology and Management of Twin Cities Metropolitan Area Lakes; Metropolitan Council of the Twin Cities Area: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, H.S.; Johengen, T.H.; Godwin, C.M.; Purcell, H.; Alsip, P.J.; Ruberg, S.A.; Mason, L.A. Continuous in situ nutrient analyzers pinpoint the onset and rate of internal P loading under anoxia in Lake Erie’s central basin. ACS ES&T Water 2021, 1, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyrer, F.; Young, M.; Patton, O.; Ayers, D. Dissolved oxygen controls summer habitat of Clear Lake Hitch (Lavinia exilicauda chi), an imperilled potamodromous cyprinid. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2020, 29, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesman, J.P.; Ayala, A.I.; Goyette, S.; Kasparian, J.; Marcé, R.; Markensten, H.; Stelzer, J.A.; Thayne, M.W.; Thomas, M.K.; Pierson, D.C.; et al. Drivers of phytoplankton responses to summer wind events in a stratified lake: A modeling study. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2022, 67, 856–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Fan, X.; Chen, H.; Feng, G. Influence of wind and light on the floating and sinking process of Microcystis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Huisman, J. Blooms like it hot. Science 2008, 320, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paerl, H.W.; Huisman, J. Climate change: A catalyst for global expansion of harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009, 1, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari-Sharabian, M.; Ahmad, S.; Karakouzian, M. Climate change and eutrophication: A short review. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2019, 8, 3668–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, D.A.; Wilkinson, G.M. Capturing the spatial variability of algal bloom development in a shallow temperate lake. Freshw. Biol. 2021, 66, 2064–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Kong, F.; Chen, Y.; Qian, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xing, P. Horizontal distribution and transport processes of bloom-forming Microcystis in a large shallow lake (Taihu, China). Limnologica 2010, 40, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, P.M.; Ibelings, B.W.; Bormans, M.; Huisman, J. Artificial mixing to control cyanobacterial blooms: A review. Aquat. Ecol. 2016, 50, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istvánovics, V.; Pettersson, K.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Pierson, D.; Padisík, J.; Colom, W. Gloeotrichia echinulata, a colonial cyanobacterium with a unique phosphorus uptake and life strategy. J. Plankton Res. 1993, 15, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiero, R.P.; Welch, E.B. Contribution of benthic blue-green algal recruitment to lake populations and phosphorus translocation. Freshw. Biol. 1992, 27, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, C.; Wells, S. Modeling cyanobacteria vertical migration. Water 2022, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caron, D.A.; Lie, A.A.Y.; Stewart, B.; Tinoco, A.; Kalra, I.; Smith, S.A.; Willingham, A.L.; Sneddon, S.; Smith, J.; Webb, E.; et al. Spatial Structure and Temporal Dynamics in Clear Lake, CA: The Role of Wind in Promoting and Sustaining Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms. Water 2025, 17, 3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223265

Caron DA, Lie AAY, Stewart B, Tinoco A, Kalra I, Smith SA, Willingham AL, Sneddon S, Smith J, Webb E, et al. Spatial Structure and Temporal Dynamics in Clear Lake, CA: The Role of Wind in Promoting and Sustaining Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms. Water. 2025; 17(22):3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223265

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaron, David A., Alle A. Y. Lie, Brittany Stewart, Amanda Tinoco, Isha Kalra, Stephanie A. Smith, Adam L. Willingham, Shawn Sneddon, Jayme Smith, Eric Webb, and et al. 2025. "Spatial Structure and Temporal Dynamics in Clear Lake, CA: The Role of Wind in Promoting and Sustaining Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms" Water 17, no. 22: 3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223265

APA StyleCaron, D. A., Lie, A. A. Y., Stewart, B., Tinoco, A., Kalra, I., Smith, S. A., Willingham, A. L., Sneddon, S., Smith, J., Webb, E., Florea, K., & Howard, M. D. A. (2025). Spatial Structure and Temporal Dynamics in Clear Lake, CA: The Role of Wind in Promoting and Sustaining Harmful Cyanobacterial Blooms. Water, 17(22), 3265. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223265