Hydrological and Geochemical Responses to Agricultural Activities in a Karst Catchment: Insights from Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Source Apportionment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

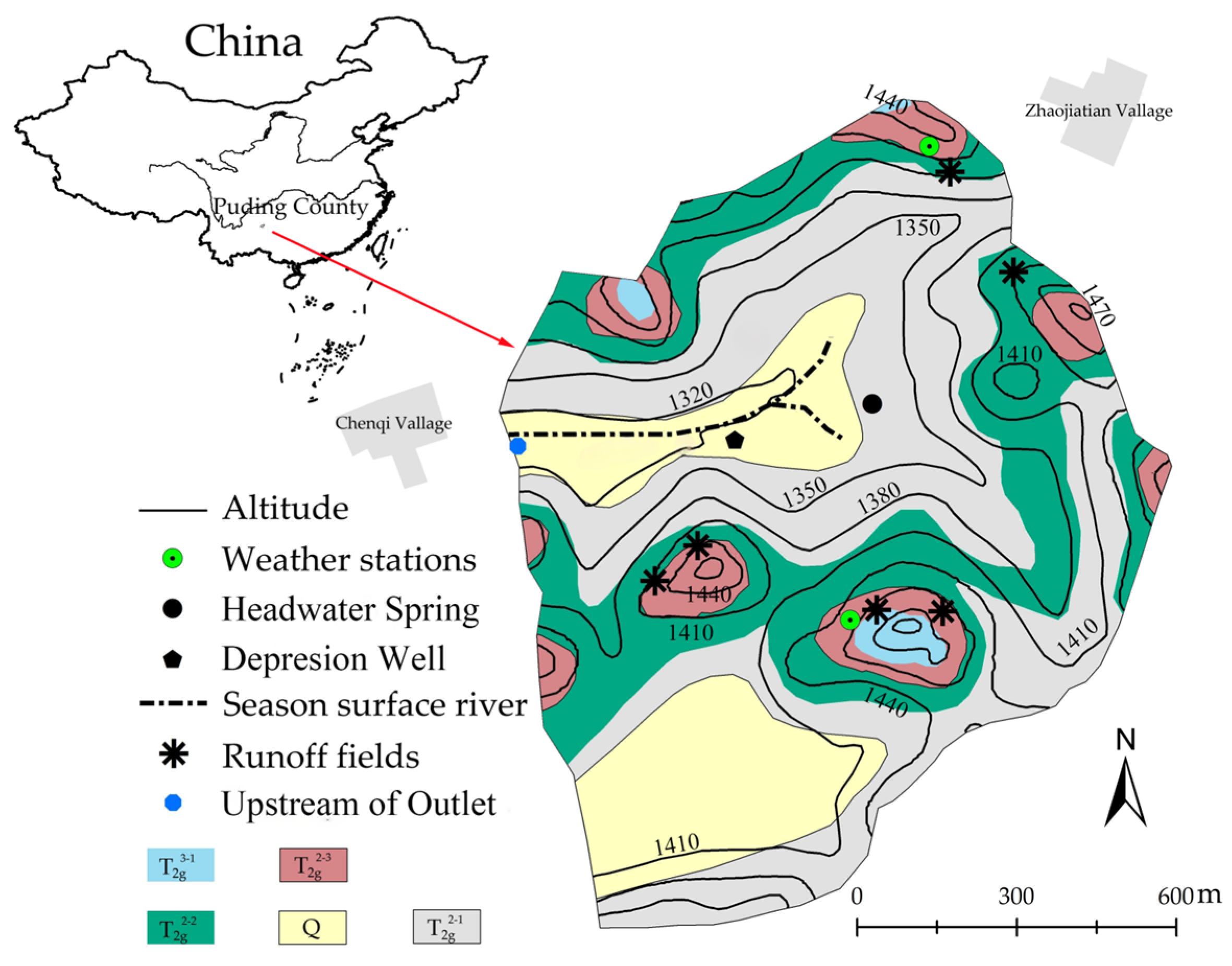

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Monitoring and Water Sampling

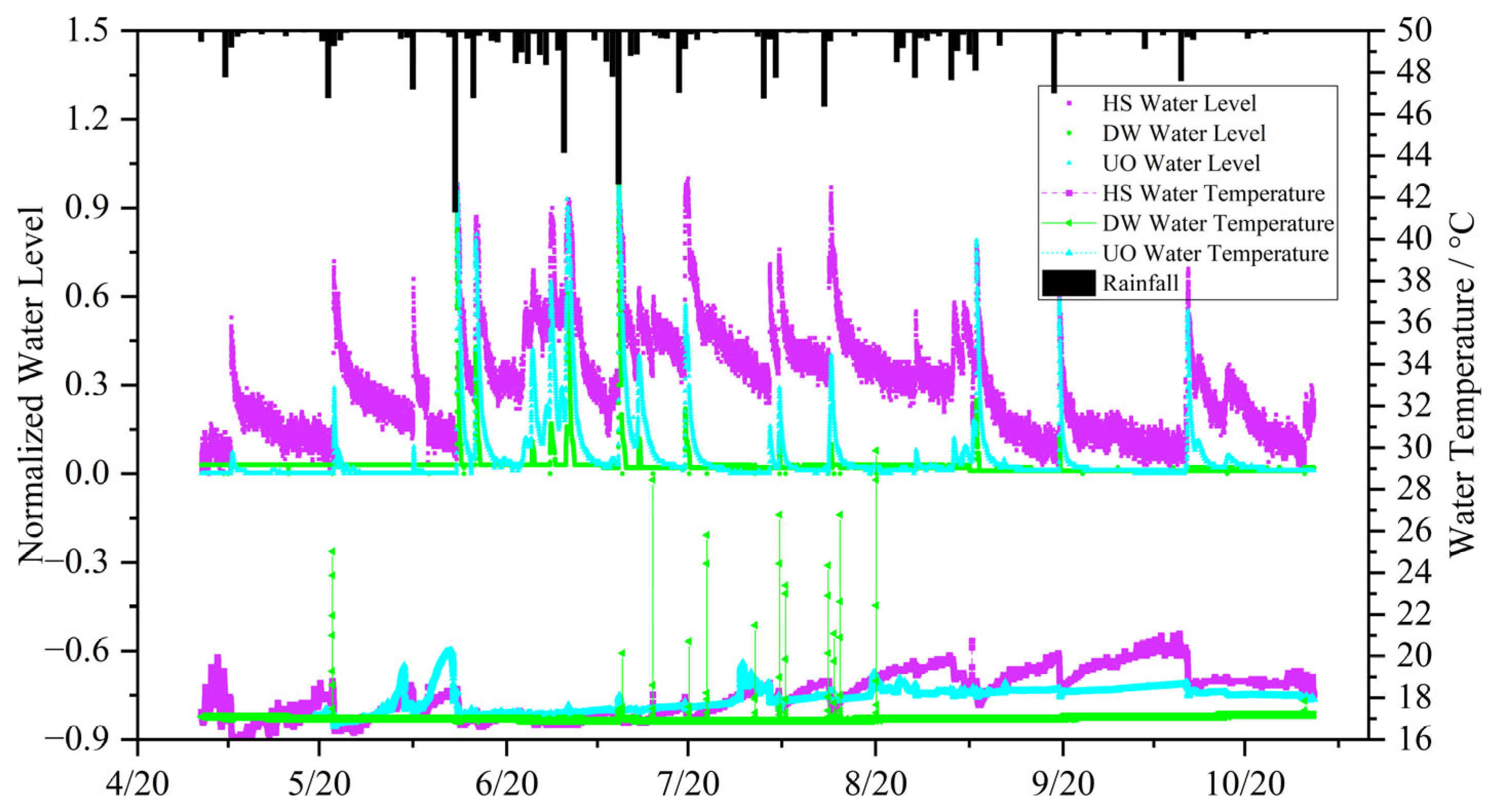

2.2.1. High-Frequency Hydrological Monitoring

2.2.2. Water Sampling and In Situ Measurements

2.3. Laboratory Analyses

2.4. Data Analysis

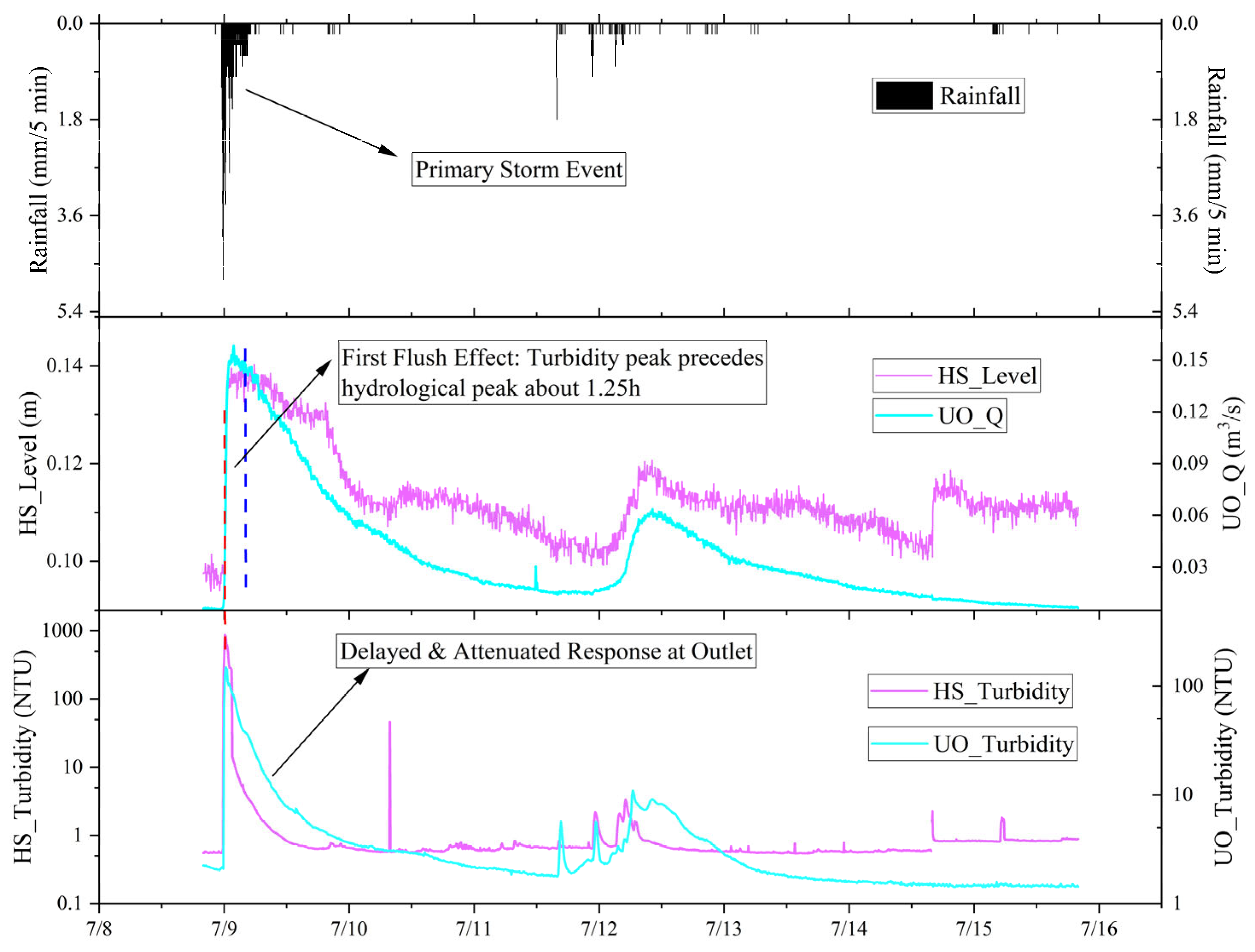

2.4.1. Hydrological Event Parameterization

2.4.2. Source Apportionment and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Hydrological Response Characteristics

3.2. Spatiotemporal Variations in Hydrochemistry

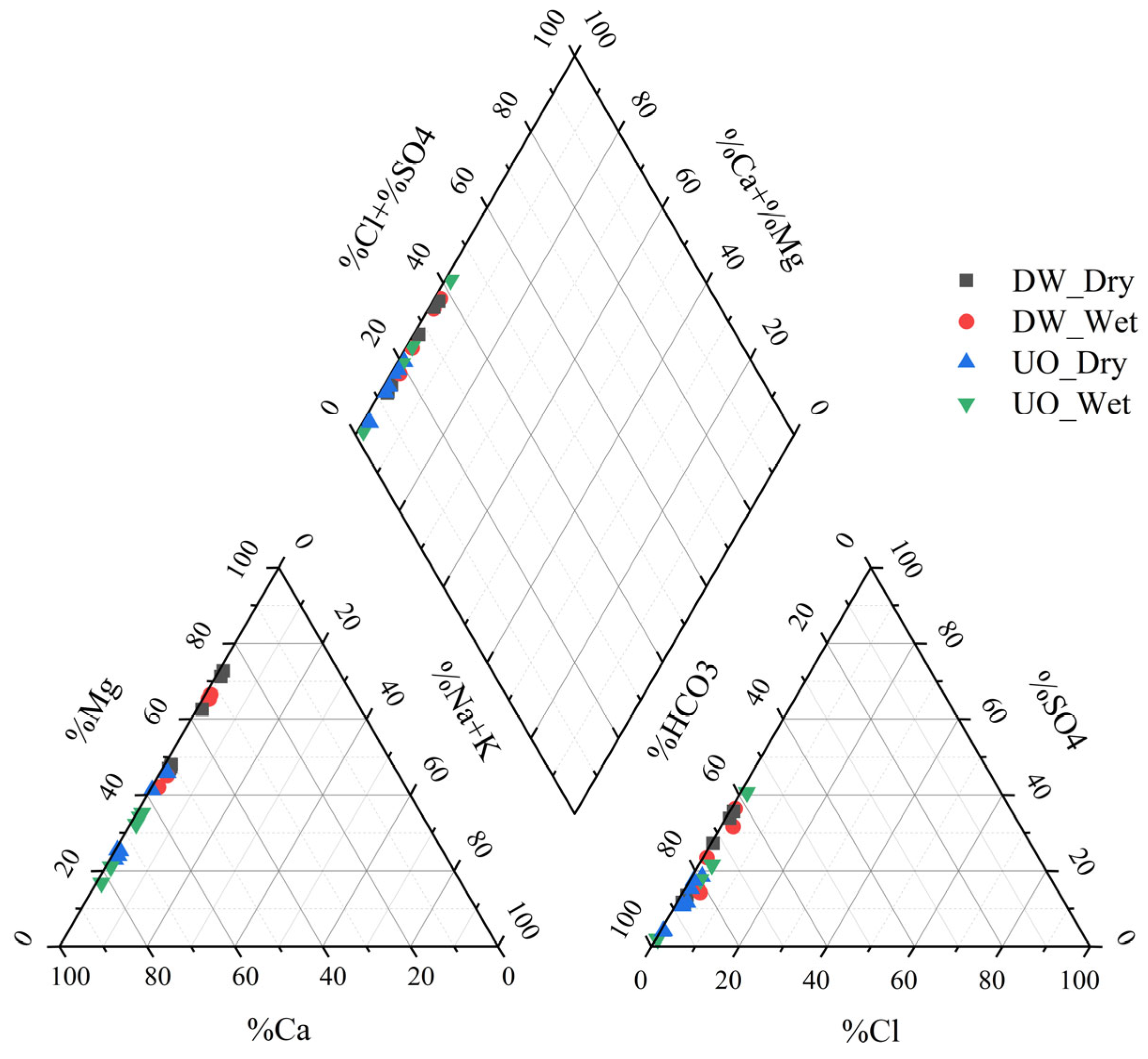

3.2.1. Hydrochemical Facies and Major Ion Composition

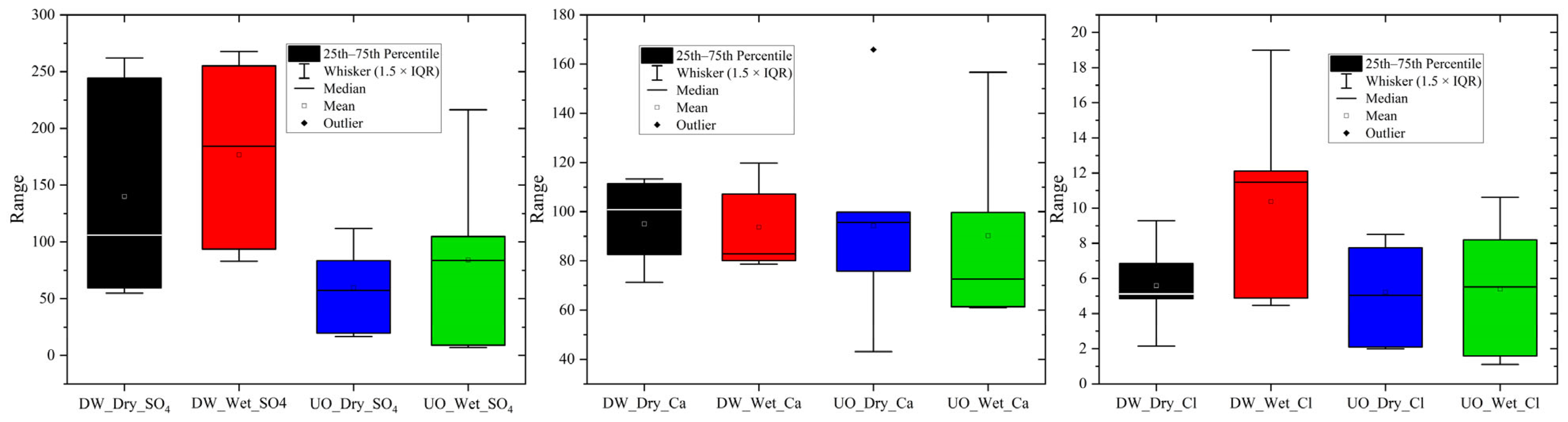

3.2.2. Spatial Differentiation and Seasonal Dynamics of Ions

3.3. Identification of Dominant Hydrochemical Processes

4. Discussion

4.1. Control of Spatial Heterogeneity on Catchment Hydro-Geochemical Responses

4.2. Source Apportionment via PCA: Decoupling Natural and Anthropogenic Processes

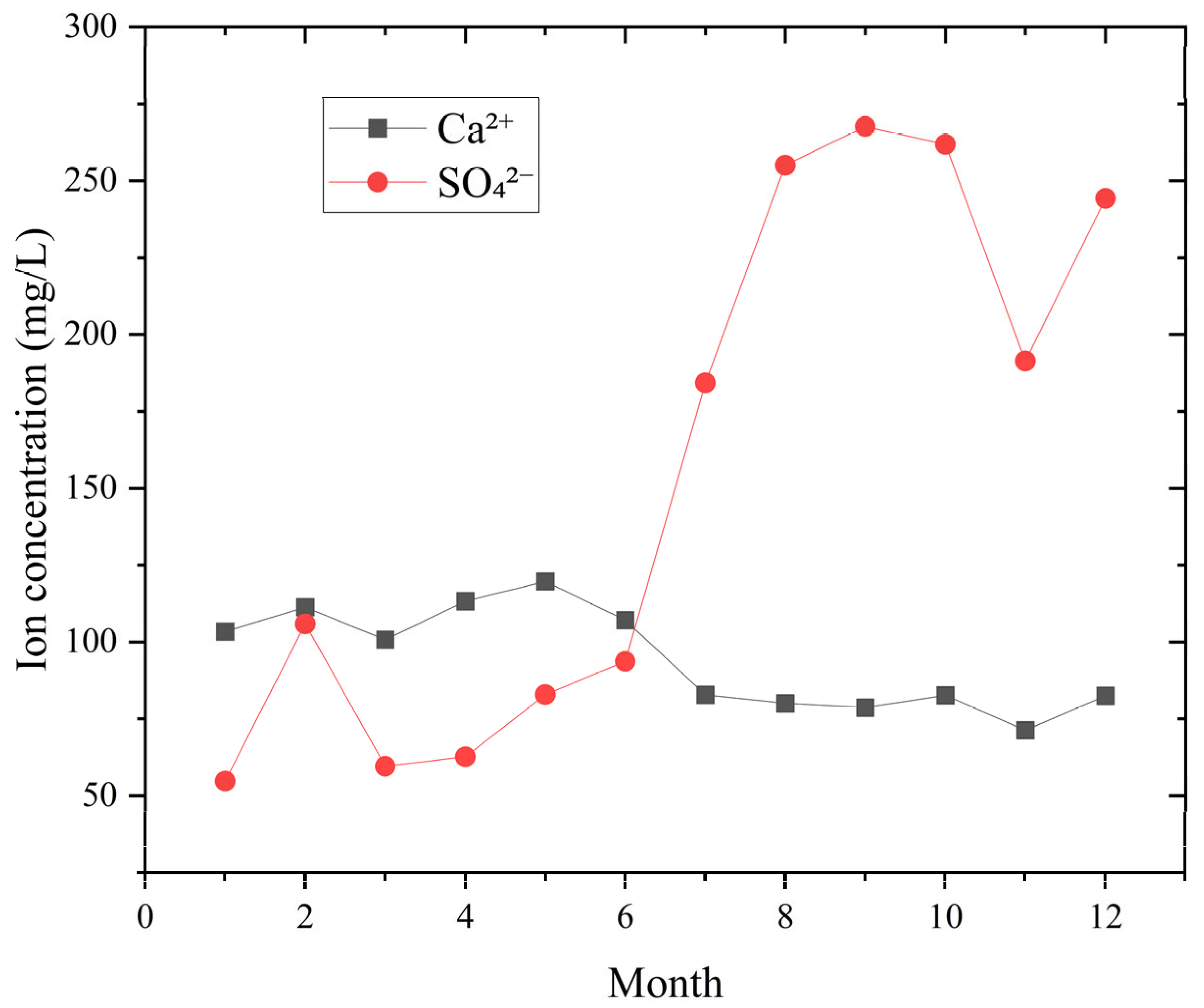

4.3. Anomalous Seasonal Dynamics of Agricultural Sulfate: A Hypothesis of “Legacy Effect” in the Karst Critical Zone

4.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HS | Headwater Spring |

| DW | Depression Well |

| UO | Upstream of Outlet |

References

- Ford, D. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaez-Montoya, C.; Bonilla, R.M.; Goldscheider, N.; Mahlknecht, J. Groundwater Salinization Patterns in the Yucatan Peninsula Reveal Contamination and Vulnerability of the Karst Aquifer. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Rong, S.; Xiong, Y.; Teng, Y. Groundwater Vulnerability and Groundwater Contamination Risk in Karst Area of Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, D.; Guo, F.; Liu, F. Unveiling the Nitrogen Transport and Transformation in Different Karst Aquifers Media. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Yang, W.; Xiong, S.; Li, X.; Niu, G.; Lu, T.; Ferrer, A.S.N. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Groundwater in Karst Areas of Southwest China: A Case Study of Bama, Guangxi. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.N.; Ortega-Camacho, D.; Acosta-Gonzalez, G.; Maria Leal-Bautista, R.; Fox, W.E.; Cejudo, E. A Multi-Approach Assessment of Land Use Effects on Groundwater Quality in a Karstic Aquifer. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.; Wu, D.; Yu, D.; Min, Y.; Huang, B.; Wang, M.; Gao, J.; Xiong, G.; Zhang, C.; Dang, X. Nitrate Sources and Migration in Rural Karst Aquifers: A Case Study in Pingyin Karst Catchment, North China. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 2025, 61, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolff, A.; Fleckenstein, J.H.; Rao, P.S.C.; Jawitz, J.W. Emergent Archetype Patterns of Coupled Hydrologic and Biogeochemical Responses in Catchments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 4143–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelibus, M.D.; Balacco, G.; Gioia, A.; Iacobellis, V.; Spilotro, G. Mass Transport Triggered by Heavy Rainfall: The Role of Endorheic Basins and Epikarst in a Regional Karst Aquifer. Hydrol. Process. 2017, 31, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ge, H.; Li, X. Impact of Land Use/Land Cover and Landscape Pattern on Water Quality in Dianchi Lake Basin, Southwest of China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Cao, M.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q. Hydrogeological Characterization and Environmental Effects of the Deteriorating Urban Karst Groundwater in a Karst Trough Valley: Nanshan, SW China. Hydrogeol. J. 2018, 26, 1487–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opsahl, S.P.; Musgrove, M.; Slattery, R.N. New Insights into Nitrate Dynamics in a Karst Groundwater System Gained from in Situ High-Frequency Optical Sensor Measurements. J. Hydrol. 2017, 546, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godsey, S.E.; Kirchner, J.W.; Clow, D.W. Concentration–Discharge Relationships Reflect Chemostatic Characteristics of US Catchments. Hydrol. Process. 2009, 23, 1844–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, K.E.; Jones, C.S.; Clark, R.J.; Libra, R.D.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.-K. Contrasting NO3-N Concentration Patterns at Two Karst Springs in Iowa (USA): Insights on Aquifer Nitrogen Storage and Delivery. Hydrogeol. J. 2019, 27, 1389–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, V.; Lefebvre, R.; Therrien, R.; Savard, M.M. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Geochemical Data as Indicative of the Hydrogeochemical Evolution of Groundwater in a Sedimentary Rock Aquifer System. J. Hydrol. 2008, 353, 294–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Groves, C.; Wu, X.; Chang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, P. Nitrate Migration and Transformations in Groundwater Quantified by Dual Nitrate Isotopes and Hydrochemistry in a Karst World Heritage Site. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 138907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, Z.; Hua, D.; Wang, F.; Ying, Q.; Ye, H. Active Species and Source Apportionment of Volatile Organic Compounds in an Industrial Park of Shenyang. Environ. Pollut. Control 2021, 43, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Güler, C.; Thyne, G.D.; McCray, J.E.; Turner, K.A. Evaluation of Graphical and Multivariate Statistical Methods for Classification of Water Chemistry Data. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hounslow, A.W. Water Quality Data: Analysis and Interpretation, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-87371-676-5. [Google Scholar]

- Helena, B.; Pardo, R.; Vega, M.; Barrado, E.; Fernandez, J.M.; Fernandez, L. Temporal Evolution of Groundwater Composition in an Alluvial Aquifer (Pisuerga River, Spain) by Principal Component Analysis. Water Res. 2000, 34, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Zou, J.; Jia, R.; Yang, Y. Hydrochemical Characteristics and Evolution under the Influence of Multiple Anthropogenic Activities in Karst Aquifers, Northern China. Water 2024, 16, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; He, S.; Yang, Y.; Wu, P.; Luo, W. Hydrochemical Fingerprints of Karst Underground River Systems Impacted by Urbanization in Guiyang, Southwest China. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2024, 264, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, T.; Wang, S. Effects of Land Use, Land Cover and Rainfall Regimes on the Surface Runoff and Soil Loss on Karst Slopes in Southwest China. Catena 2012, 90, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Hua, M.; Luo, W.; Guo, W. Research Progress of Nitrate Tracing in Karst Groundwater Based on CiteSpace. Carsologica Sin. 2024, 43, 563–574. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Chen, J.; He, C.; Ren, S.; Liu, G. Multi-Method Characterization of Groundwater Nitrate and Sulfate Contamination by Karst Mines in Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, J.; Yuan, D.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, H. Hydrogeochemistry and Possible Sulfate Sources in Karst Groundwater in Chongqing, China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 68, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, M.H.; Pinjung, Z.; Mikita, V.; Bence, C.; Szűcs, P. A Novel Integration of Self-Organizing Maps and NETPATH Inverse Modeling to Trace Uranium and Toxic Metal Contamination Risks in West Mecsek, Hungary. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 496, 139291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipović, M.; Terzić, J.; Lukač Reberski, J.; Vlahović, I. Utilizing a Multi-Tracer Method to Investigate Sulphate Contamination: Novel Insights on Hydrogeochemical Characteristics of Groundwater in Intricate Karst Systems. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 27, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, S.; Cheng, Q.; Fryar, A.E.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yue, F.; Peng, T. Factors Controlling Discharge-Suspended Sediment Hysteresis in Karst Basins, Southwest China: Implications for Sediment Management. J. Hydrol. 2021, 594, 125792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, P.; Liu, Q.; Sun, C.; Yang, Y.; He, G.; He, C. Equivalent Nodal Intensity-Based Contact Model for 3D Finite–Discrete Element Method in Rock Fracturing Analysis. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 6059–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zuo, R.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Teng, Y.; Shi, R.; Zhai, Y. Apportionment and Evolution of Pollution Sources in a Typical Riverside Groundwater Resource Area Using PCA-APCS-MLR Model. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2018, 218, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Song, N.; Li, Y. An In-Depth Investigation of the Influence of Sample Size on PCA-MLR, PMF, and FA-NNC Source Apportionment Results. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 5841–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, M.E.; Boyer, E.W.; Dent, C.L.; Gergel, S.E.; Grimm, N.B.; Groffman, P.M.; Hart, S.C.; Harvey, J.W.; Johnston, C.A.; Mayorga, E.; et al. Biogeochemical Hot Spots and Hot Moments at the Interface of Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecosystems. Ecosystems 2003, 6, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.B.; Dean, R.W. Exchange of Water between Conduits and Matrix in the Floridan Aquifer. Chem. Geol. 2001, 179, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudarra, M.; Andreo, B. Relative Importance of the Saturated and the Unsaturated Zones in the Hydrogeological Functioning of Karst Aquifers: The Case of Alta Cadena (Southern Spain). J. Hydrol. 2011, 397, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, J.; Qian, H.; Lyu, X.; Liu, H. Origin and Assessment of Groundwater Pollution and Associated Health Risk: A Case Study in an Industrial Park, Northwest China. Environ. Geochem. Health 2014, 36, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Liu, W. Hydrochemical Evolution Processes of Karst Groundwater in Guiyang City: Evidences from Hydrochemistry and ~87Sr/~86Sr Ratios. Earth Sci. 2019, 44, 2829–2838. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, G.; Sun, B.; Wang, Y. Characteristics and Processes of Hydrogeochemical Evolution Induced by Long-Term Mining Activities in Karst Aquifers, Southwestern China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 30055–30068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C.A.J.; Postma, D. Geochemistry, Groundwater and Pollution; Appelo, C.A.J., Postma, D., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-429-15232-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lorette, G.; Sebilo, M.; Buquet, D.; Lastennet, R.; Denis, A.; Peyraube, N.; Charriere, V.; Studer, J.-C. Tracing Sources and Fate of Nitrate in Multilayered Karstic Hydrogeological Catchments Using Natural Stable Isotopic Composition (δ15N-NO3- and δ18O-NO3-). Application to the Toulon Karst System (Dordogne, France). J. Hydrol. 2022, 610, 127972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, X.; Jiang, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W.; Duan, Y.; Luo, W.; Mao, Z.; Wang, Y. Multiple Contamination Sources, Pathways and Conceptual Model of Complex Buried Karst Water System: Constrained by Hydrogeochemistry and S2H, S18O, S34S, S13C and 87Sr/ 86Sr Isotopes. J. Hydrol. 2024, 639, 131614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, D.J.; Green, M.B.; Campbell, J.L.; Chamblee, J.F.; Chaoka, S.; Fraterrigo, J.M.; Kaushal, S.S.; Martin, S.L.; Jordan, T.E.; Parolari, A.J.; et al. Legacy Effects in Material Flux: Structural Catchment Changes Predate Long-Term Studies. Bioscience 2012, 62, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Shen, H.; Hu, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dahlgren, R.A. Legacy Nutrient Dynamics at the Watershed Scale: Principles, Modeling, and Implications. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 149, pp. 237–313. ISBN 978-0-12-815177-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ballard, T.C.; Michalak, A.M.; McIsaac, G.F.; Rabalais, N.N.; Turner, R.E. Comment on “Legacy Nitrogen May Prevent Achievement of Water Quality Goals in the Gulf of Mexico”. Science 2019, 365, eaau8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Luo, L.; Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Ren, Q.; Wang, Y. Legacy Nitrogen Impeding the Achievement of Nitrogen Management Targets: Evidence from China’s First Cross-Provincial Ecological Compensation Watershed. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 38, 104178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Pan, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Hu, M.; Cheng, Z.; Zheng, X.; Chen, D. Influence of Land Use and Landscape Pattern on Legacy Nitrogen Pollution in a Typical Watershed in Eastern China. Catena 2025, 256, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, N.; Zhu, X.; Huang, S.; Lu, C.; Liu, K.; Zhou, F.; Smith, P.; Tian, H.; et al. Legacy Effects Cause Systematic Underestimation of N2O Emission Factors. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Wei, Y.; Wu, K.; Wu, H.; Jiao, X.; Hu, M.; Chen, D. Modification of Exploration of Long-Term Nutrient Trajectories for Nitrogen (ELEMeNT-N) Model to Quantify Legacy Nitrogen Dynamics in a Typical Watershed of Eastern China. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 064005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puckett, L.J.; Tesoriero, A.J.; Dubrovsky, N.M. Nitrogen Contamination of Surficial Aquifers-A Growing Legacy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, N.B.; Van Meter, K.J.; Byrnes, D.K.; Van Cappellen, P.; Brouwer, R.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Jarsjö, J.; Rudolph, D.L.; Cunha, M.C.; Nelson, N.; et al. Managing Nitrogen Legacies to Accelerate Water Quality Improvement. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Zhou, A.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Pan, G.; He, N. Response of Antimony and Arsenic in Karst Aquifers and Groundwater Geochemistry to the Influence of Mine Activities at the World’s Largest Antimony Mine, Central China. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 127131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Li, W.; Su, C.; Zhao, L.; Wei, F.; Chen, Z.; Liang, C. Indication of Hydrochemistry and δ34S-SO42− on Sulfate Pollution of Groundwater in Daye Mining Area. Earth Sci. 2023, 48, 3432–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Event No. | Date | Total P (mm) | Peak P (mm/h) | Duration (h) | Parameter | HS | DW | UO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12-June | 84.6 | 46.2 | 5.25 | T_lag (h) | 1.25 | 1.75 | 1.5 |

| T_peak (h) | 0.75 | 1.5 | 1.08 | |||||

| T_r50 (h) | 31.25 | 3.33 | 12.25 | |||||

| 2 | 15-June | 28.4 | 10.8 | 5.58 | T_lag (h) | 0.83 | 2.42 | 0.83 |

| T_peak (h) | 2.67 | 2.67 | 2.67 | |||||

| T_r50 (h) | 39.67 | 5.67 | 13.42 | |||||

| 3 | 30-June | 50.2 | 8.2 | 16.08 | T_lag (h) | 3.75 | 4.25 | 2.5 |

| T_peak (h) | 7.08 | 4.67 | 6.5 | |||||

| T_r50 (h) | 51.33 | 7.67 | 17 | |||||

| 4 | 20-July | 19.8 | 12.4 | 4.41 | T_lag (h) | 1.17 | 2.08 | 1.25 |

| T_peak (h) | 2.25 | 1.83 | 2.42 | |||||

| T_r50 (h) | 64.74 | 3.92 | 14.5 | |||||

| 5 | 9-July | 65.2 | 30.8 | 5.67 | T_lag (h) | 0.5 | 0.58 | 0.33 |

| T_peak (h) | 1.58 | 2.25 | 2 | |||||

| T_r50 (h) | 30.8 | 5.42 | 16.17 | |||||

| Mean ± SD | T_lag (h) | 1.50 ± 1.27 | 2.22 ± 1.33 | 1.28 ± 0.80 | ||||

| T_peak (h) | 2.87 ± 2.49 | 2.58 ± 1.23 | 2.93 ± 2.14 | |||||

| T_r50 (h) | 43.56 ± 14.24 | 5.20 ± 1.72 | 14.67 ± 1.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, L.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, S.; Xu, S.; He, Q.; Li, Y.; Peng, T.; Wang, S. Hydrological and Geochemical Responses to Agricultural Activities in a Karst Catchment: Insights from Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Source Apportionment. Water 2025, 17, 3264. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223264

Cao L, Cheng Q, Wang S, Xu S, He Q, Li Y, Peng T, Wang S. Hydrological and Geochemical Responses to Agricultural Activities in a Karst Catchment: Insights from Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Source Apportionment. Water. 2025; 17(22):3264. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223264

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Le, Qianyun Cheng, Shangqing Wang, Shaoqiang Xu, Qirui He, Yanqiu Li, Tao Peng, and Shijie Wang. 2025. "Hydrological and Geochemical Responses to Agricultural Activities in a Karst Catchment: Insights from Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Source Apportionment" Water 17, no. 22: 3264. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223264

APA StyleCao, L., Cheng, Q., Wang, S., Xu, S., He, Q., Li, Y., Peng, T., & Wang, S. (2025). Hydrological and Geochemical Responses to Agricultural Activities in a Karst Catchment: Insights from Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Source Apportionment. Water, 17(22), 3264. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223264