Boosting Denitrification in Pyrite Bioretention Through Biochar-Mediated Electron Transfer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

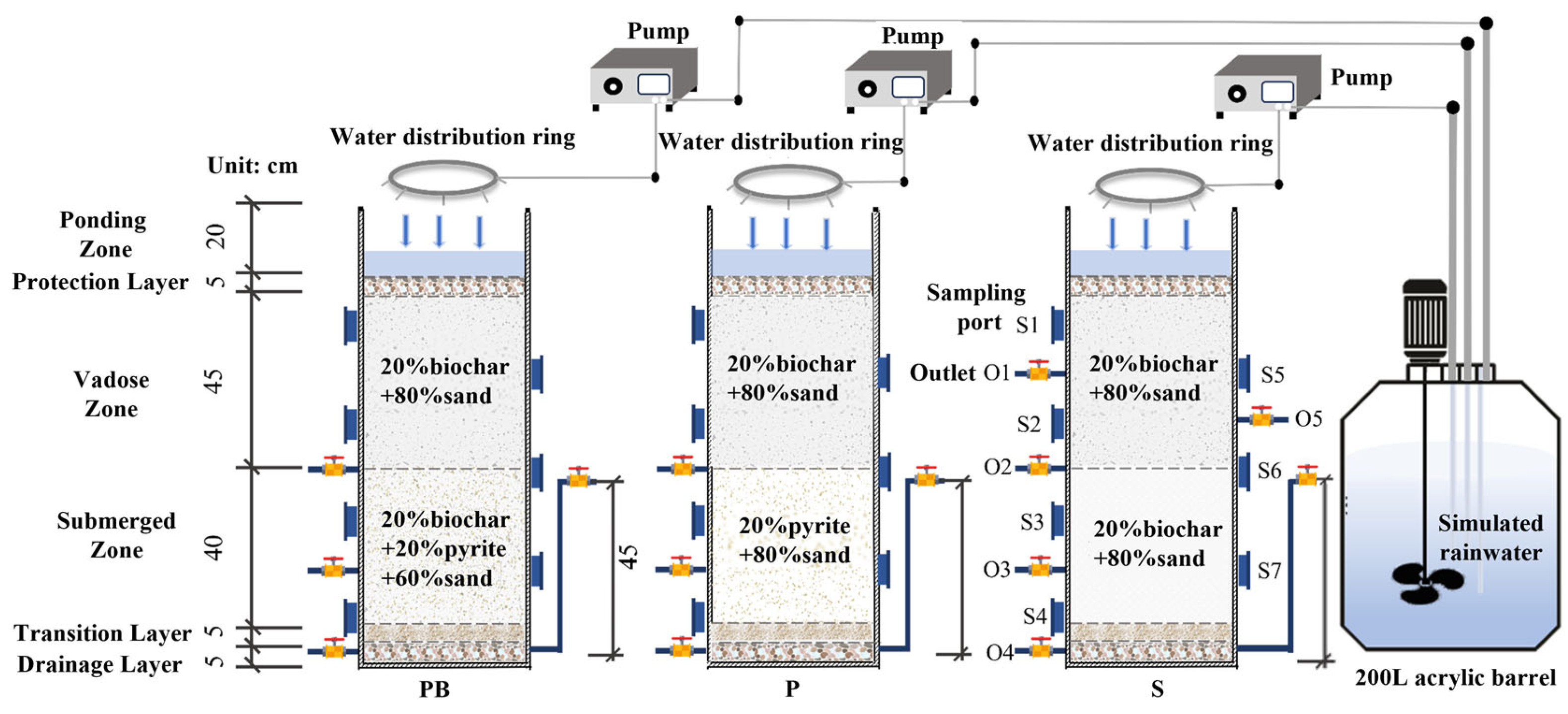

2.1. Bioretention Systems Establishment

2.2. Simulated Stormwater Preparation

2.3. Experimental Procedures

2.4. Sample Collection and Analysis

2.5. Determination of Biochar Electron Donation and Electron Acceptance Capacities

2.6. DNA Extraction and Microbial Community Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pollutant Removal Efficiency of Bioretention Systems Under Different Rainfall Conditions

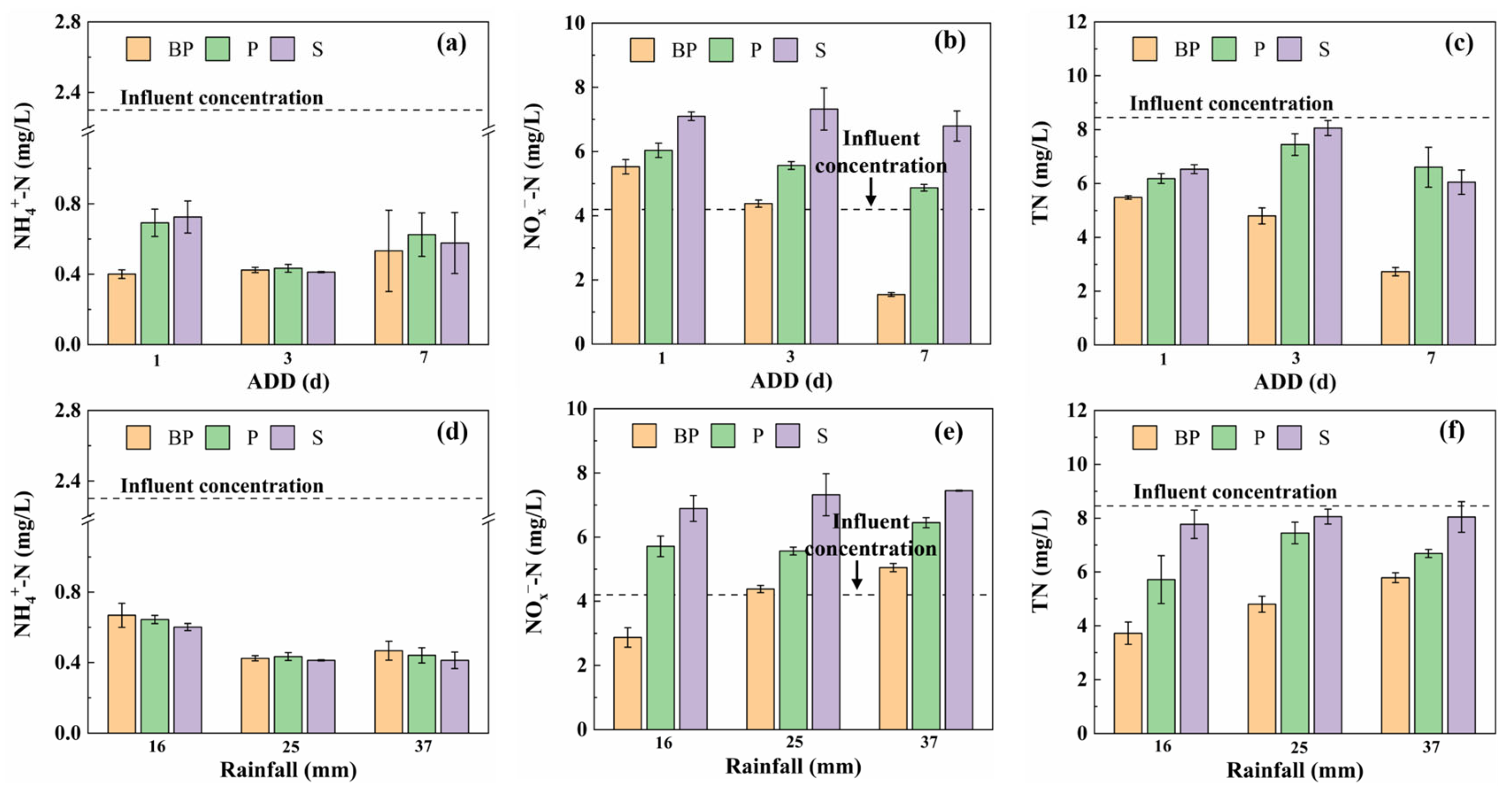

3.1.1. Nitrogen Removal Efficiency

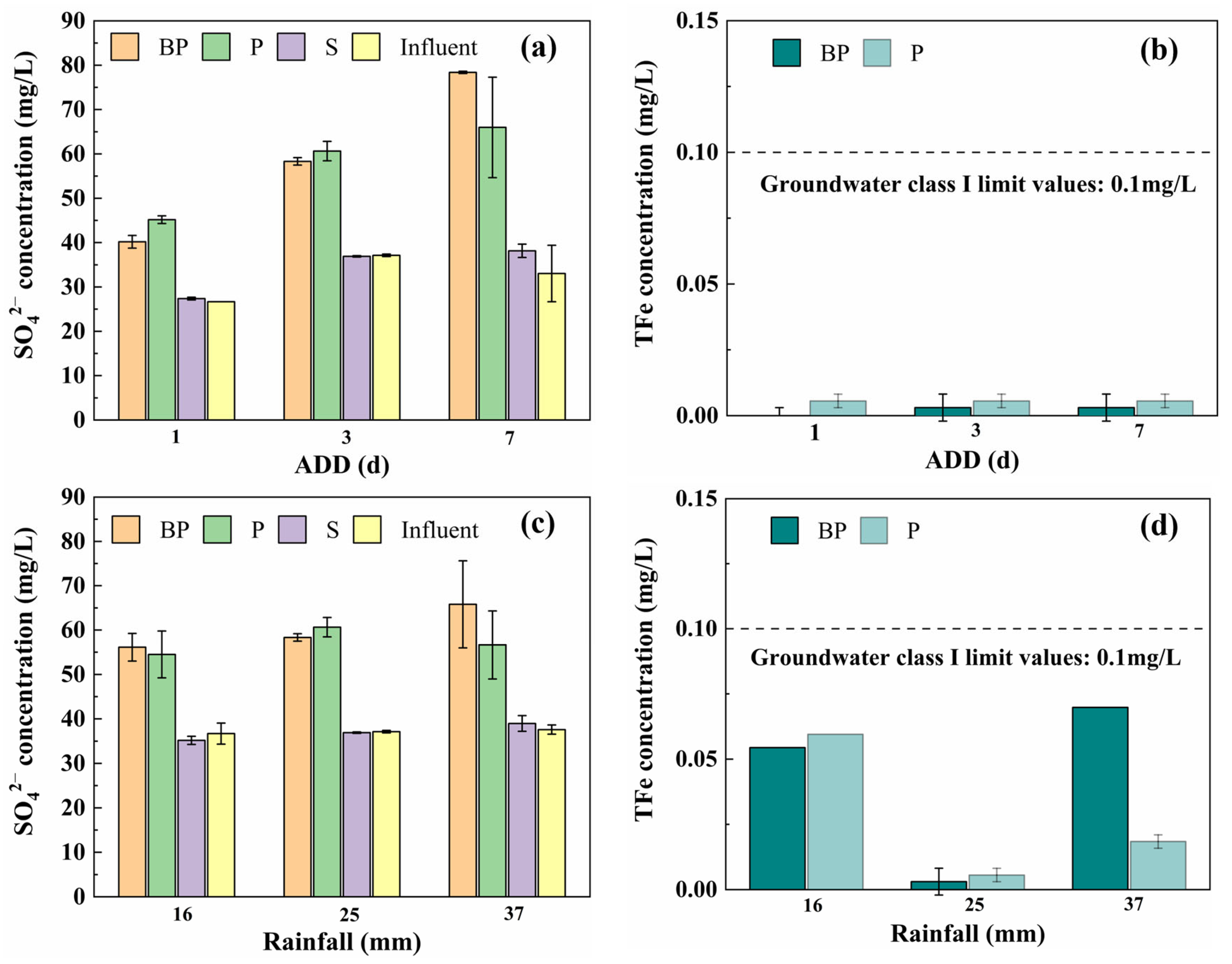

3.1.2. By-Product Leaching

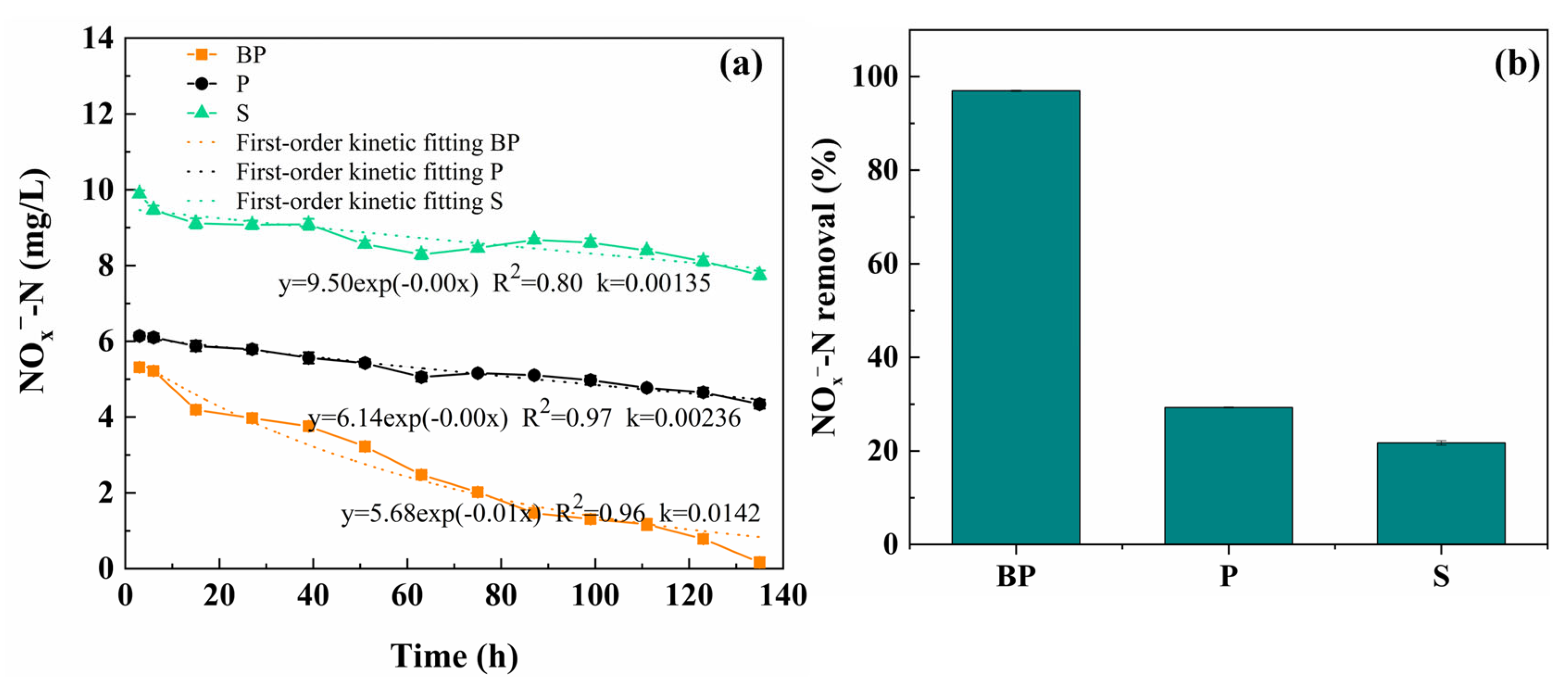

3.2. Porewater Pollutant Concentration Variation in the Submerged Zone During ADD

3.3. Chemical Property Changes in Bioretention System Media Materials

3.3.1. Biochar Surface Morphology and Electrochemical Properties

3.3.2. Pyrite Surface Morphology and XPS Characterization

3.4. Microbial Community Characteristics of Bioretention Systems

3.5. Mechanism of Denitrification in Bioretention Systems Modified with Biochar and Pyrite

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| S | Sand-based bioretention system |

| P | Pyrite-based bioretention system |

| BP | Biochar–pyrite bioretention system |

| NOx−-N | Nitrate and Nitrite |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| C/N ratio | Carbon to Nitrogen ratio |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| SCMs | Stormwater Control Measures |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand) |

| DON | Dissolved Organic Nitrogen |

| NO3−-N | Nitrate |

| PO43−-P | Phosphorate |

| TFe | Total iron |

| ETSA | Electron Transfer System Activity |

| 16SrRNA | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| ADD | Antecedent Drying Duration |

| HRT | Hydraulic Retention Time |

| SO42− | Sulfate |

| EET | Extracellular Electron Transfer |

| EAC | Electron Acceptance Capacity |

| EDC | Electron Donation Capacity |

| EDS | Energy Dispersive Spectrometer |

| MER | Mediated Electrochemical Reduction |

| MEO | Mediated Electrochemical Oxidation |

References

- Kayhanian, M.; Fruchtman, B.D.; Gulliver, J.S.; Montanaro, C.; Ranieri, E.; Wuertz, S. Review of highway runoff characteristics: Comparative analysis and universal implications. Water Res. 2012, 46, 6609–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.S.; Winston, R.J.; Wituszynski, D.M.; Tirpak, R.A.; Boening-Ulman, K.M.; Martin, J.F. Effects of watershed-scale green infrastructure retrofits on urban stormwater quality: A paired watershed study to quantify nutrient and sediment removal. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 186, 106835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFevre, G.H.; Paus, K.H.; Natarajan, P.; Gulliver, J.S.; Novak, P.J.; Hozalski, R.M. Review of Dissolved Pollutants in Urban Storm Water and Their Removal and Fate in Bioretention Cells. J. Environ. Eng. 2015, 141, 04014050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratieres, K.; Fletcher, T.D.; Deletic, A.; Zinger, Y. Nutrient and sediment removal by stormwater biofilters: A large-scale design optimisation study. Water Res. 2008, 42, 3930–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søberg, L.C.; Viklander, M.; Blecken, G.-T. Nitrogen removal in stormwater bioretention facilities: Effects of drying, temperature and a submerged zone. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 169, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirpak, R.A.; Afrooz, A.R.M.N.; Winston, R.J.; Valenca, R.; Schiff, K.; Mohanty, S.K. Conventional and amended bioretention soil media for targeted pollutant treatment: A critical review to guide the state of the practice. Water Res. 2021, 189, 116648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Z.; Song, Y.; Shao, Z.; Chai, H. Biochar-pyrite bi-layer bioretention system for dissolved nutrient treatment and by-product generation control under various stormwater conditions. Water Res. 2021, 206, 117737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Coffin, E.S.; Sheng, Y.; Duley, M.L.; Khalifa, Y.M. Microbial reduction of Fe(III) in nontronite: Role of biochar as a redox mediator. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2023, 345, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Shao, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, M.; Yuan, Y.; Li, G.; Wei, Y.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.; et al. Comprehensive evaluation of stormwater pollutants characteristics, purification process and environmental impact after low impact development practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association; American Water Works Association; Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1870039 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Wan, R.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, X.; Su, Y.; Li, M. Effect of CO2 on Microbial Denitrification via Inhibiting Electron Transport and Consumption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9915–9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Q.; Zhao, L.; Wu, W. Nitrogen removal performance in pilot-scale solid-phase denitrification systems using novel biodegradable blends for treatment of waste water treatment plants effluent. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 305, 122994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Yue, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, A.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X. A bilayer media bioretention system for enhanced nitrogen removal from road runoff. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 705, 135893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Dynamic adsorption behavior of methylene blue onto oil palm shell granular activated carbon prepared by microwave heating. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 203, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.W.; Valenca, R.; Miao, Y.; Ravi, S.; Mahendra, S.; Mohanty, S.K. Biochar increases nitrate removal capacity of woodchip biofilters during high-intensity rainfall. Water Res. 2019, 165, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Zhi, Y.; Kong, Z.; Ma, H.; Shao, Z.; Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, F.; Xu, Y.; et al. Enhancing nitrogen and phosphorus removal in plant-biochar-pyrite stormwater bioretention systems: Impact of temperature and high-frequency heavy rainfall. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yan, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H.; Geng, R.; Sun, S.; Guan, X. Coupling of selenate reduction and pyrrhotite oxidation by indigenous microbial consortium in natural aquifer. Water Res. 2023, 238, 119987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Cao, X. Biochar as both electron donor and electron shuttle for the reduction transformation of Cr(VI) during its sorption. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 244, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14848-2017; Standard for Groundwater Quality. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Wang, H.; Feng, M.; Zhou, F.; Huang, X.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Zhang, W. Effects of atmospheric ageing under different temperatures on surface properties of sludge-derived biochar and metal/metalloid stabilization. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Ma, Z.; Yang, K.; Cui, Q.; Wang, K.; Wang, T.; Wu, G.-L.; Zheng, J. Effect of three artificial aging techniques on physicochemical properties and Pb adsorption capacities of different biochars. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Hao, Y.J.H.; Wang, X. Changes in the Physicochemical Characteristics of Peanut Straw Biochar after Freeze-Thaw and Dry-Wet Aging Treatments of the Biomass. BioResources 2019, 14, 4329–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappler, A.; Wuestner, M.L.; Ruecker, A.; Harter, J.; Halama, M.; Behrens, S. Biochar as an Electron Shuttle between Bacteria and Fe(III) Minerals. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2014, 1, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquing, J.M.; Yu, Y.-H.; Chiu, P.C. Wood-Derived Black Carbon (Biochar) as a Microbial Electron Donor and Acceptor. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tan, S.N.; Glenn, A.M.; Harmer, S.; Bhargava, S.; Chen, M. A direct observation of bacterial coverage and biofilm formation byAcidithiobacillus ferrooxidanson chalcopyrite and pyrite surfaces. Biofouling 2015, 31, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Sumona, M.; Gupta, B.S.; Sun, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhan, X. Utilization of iron sulfides for wastewater treatment: A critical review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2017, 16, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhliga, I.; Nesbittb, R.S.H.W.; Laajalehtoc, K. Surface states and reactivity of pyrite and marcasite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2001, 179, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Dong, Y.; Fu, D.; Gao, N.; Ma, J.; Liu, X. Chloramphenicol removal by zero valent iron activated peroxymonosulfate system: Kinetics and mechanism of radical generation. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, R.; Xiao, L.; Zhan, X. Iron sulphides mediated autotrophic denitrification: An emerging bioprocess for nitrate pollution mitigation and sustainable wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2020, 179, 115914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Jing, Z.; Tao, Z.; Luo, H.; Zuo, S. Improvements of nitrogen removal and electricity generation in microbial fuel cell-constructed wetland with extra corncob for carbon-limited wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, V.; Bailey, J.V.; Teske, A. Phylogenetic and morphologic complexity of giant sulphur bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 104, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.H.; Mielczarek, A.T.; Kragelund, C.; Nielsen, J.L.; Saunders, A.M.; Kong, Y.; Hansen, A.A.; Vollertsen, J. A conceptual ecosystem model of microbial communities in enhanced biological phosphorus removal plants. Water Res. 2010, 44, 5070–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Liang, J.; Fan, Y.; Gu, X.; Wu, J. Response of nitrite accumulation, sludge characteristic and microbial transition to carbon source during the partial denitrification (PD) process. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 894, 165043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Luo, F.; Ma, H.; Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Liu, R.; Qiu, L.; Zu, H. Boosting Denitrification in Pyrite Bioretention Through Biochar-Mediated Electron Transfer. Water 2025, 17, 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223263

Xu Y, Yang X, Luo F, Ma H, Huang C, Xu Z, Liu R, Qiu L, Zu H. Boosting Denitrification in Pyrite Bioretention Through Biochar-Mediated Electron Transfer. Water. 2025; 17(22):3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223263

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Ying, Xiaoqin Yang, Fanxiao Luo, Haiyuan Ma, Cong Huang, Zheng Xu, Rui Liu, Lu Qiu, and Haifa Zu. 2025. "Boosting Denitrification in Pyrite Bioretention Through Biochar-Mediated Electron Transfer" Water 17, no. 22: 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223263

APA StyleXu, Y., Yang, X., Luo, F., Ma, H., Huang, C., Xu, Z., Liu, R., Qiu, L., & Zu, H. (2025). Boosting Denitrification in Pyrite Bioretention Through Biochar-Mediated Electron Transfer. Water, 17(22), 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223263