Delineation Using Multi-Tracer Tests and Hydrochemical Investigation of the Matica River Catchment at Plitvice Lakes, Croatia

Abstract

1. Introduction

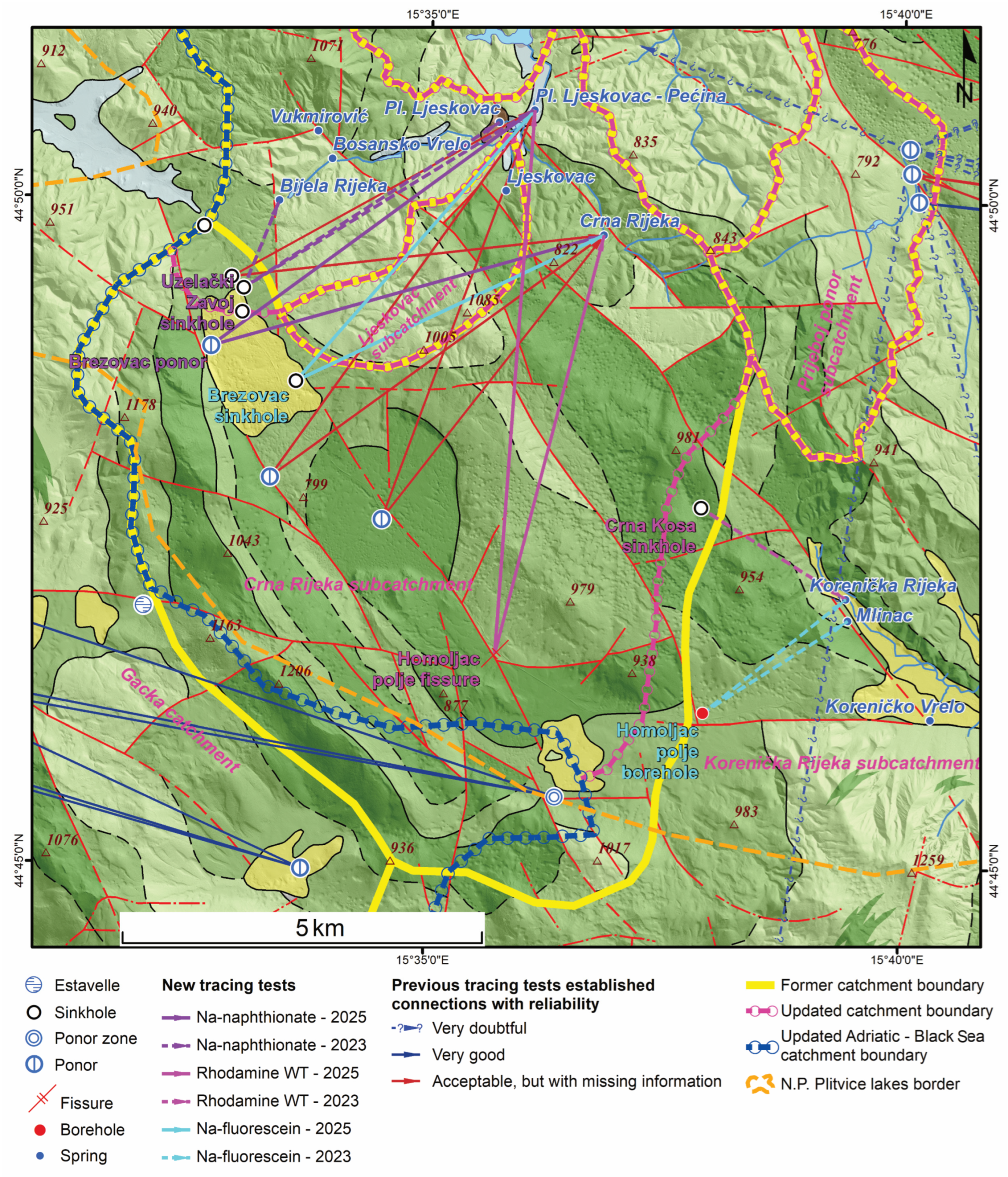

2. Materials and Methods

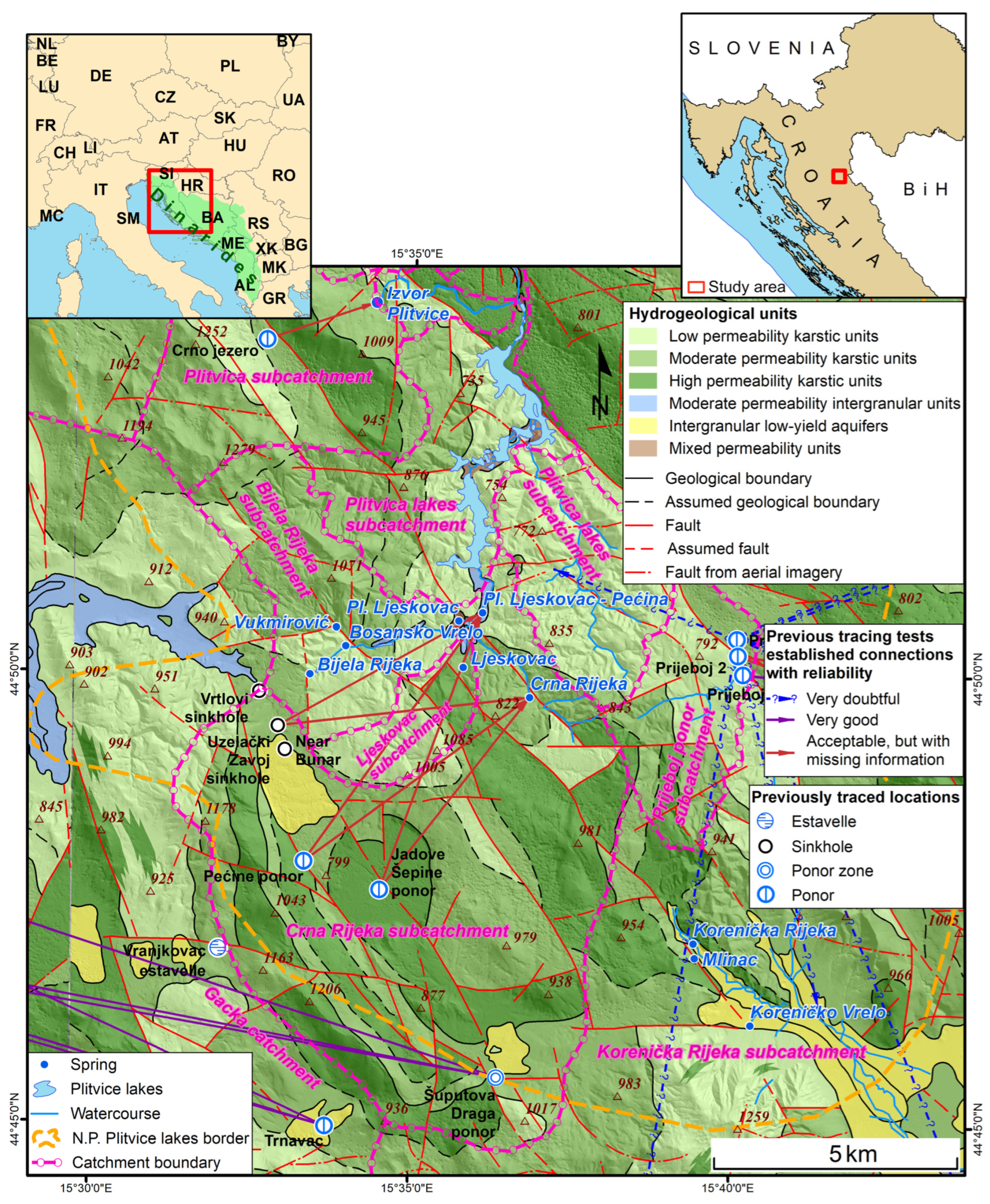

2.1. Setting

2.2. Hydrogeological Characteristics

2.3. Methods and Data

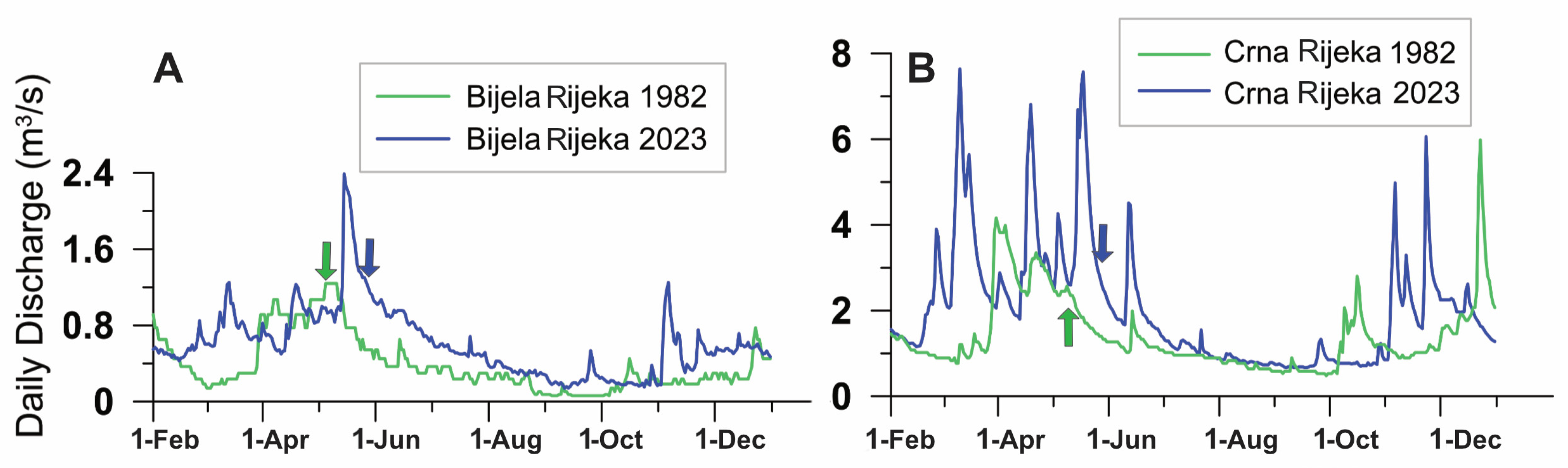

3. Results

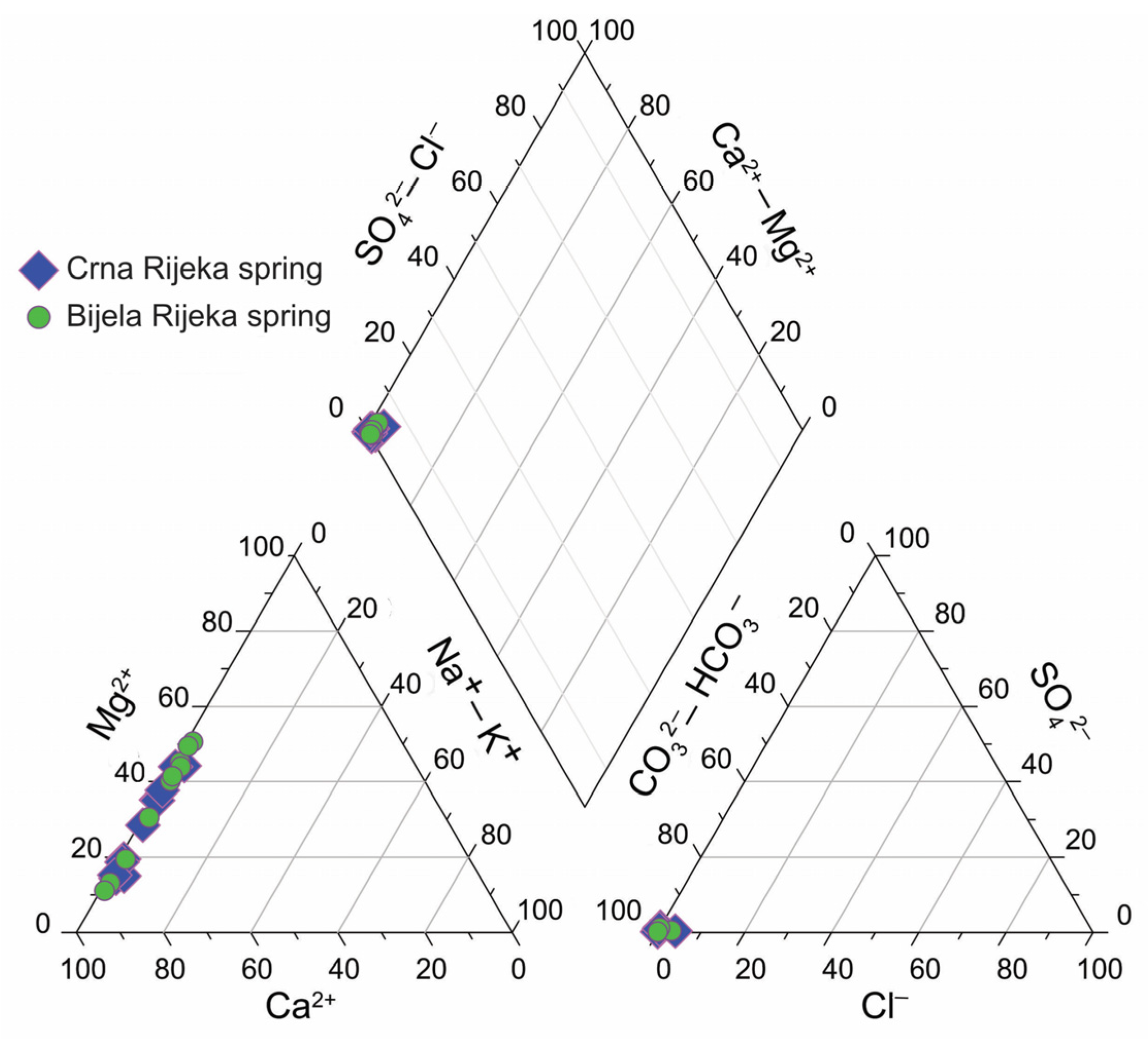

3.1. Hydrochemical

3.2. Previous Tracer Tests

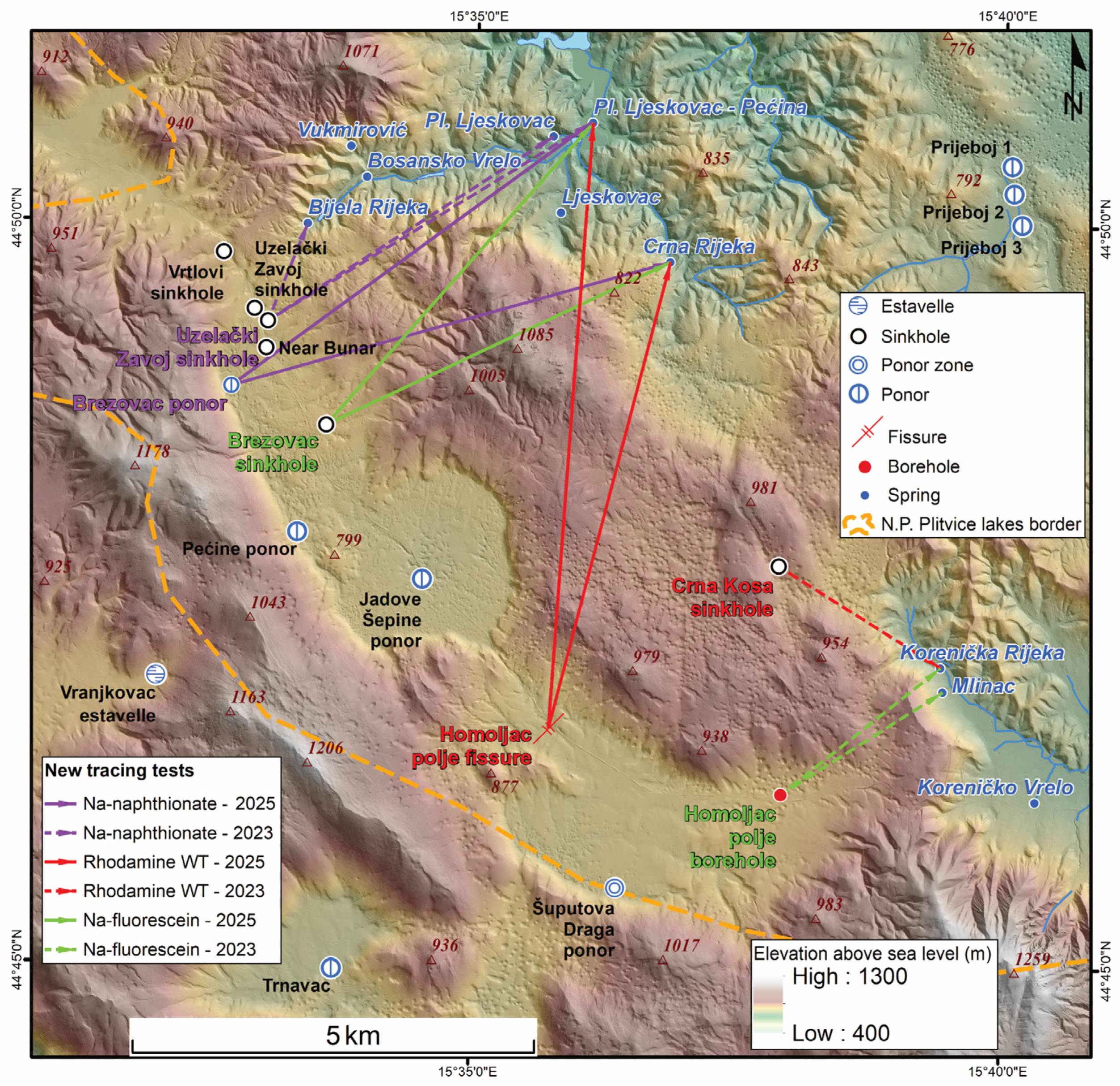

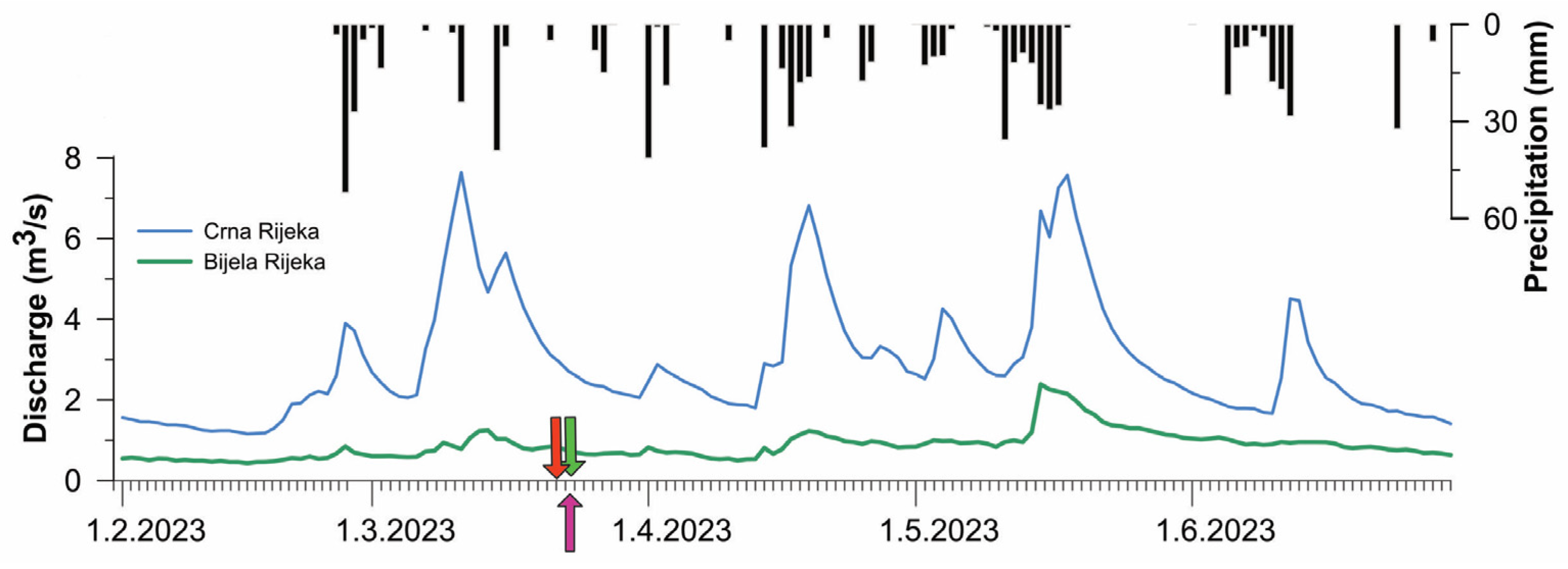

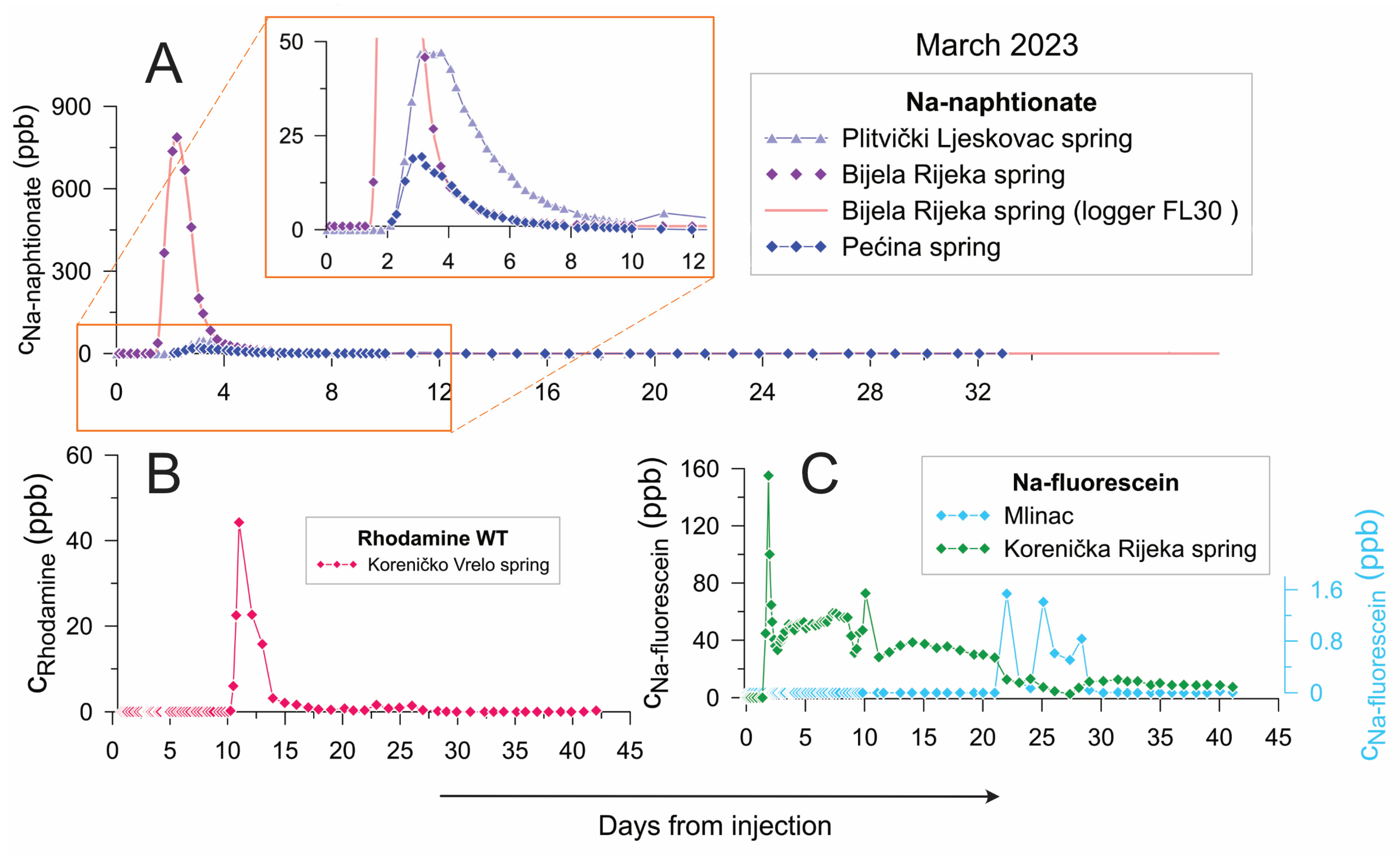

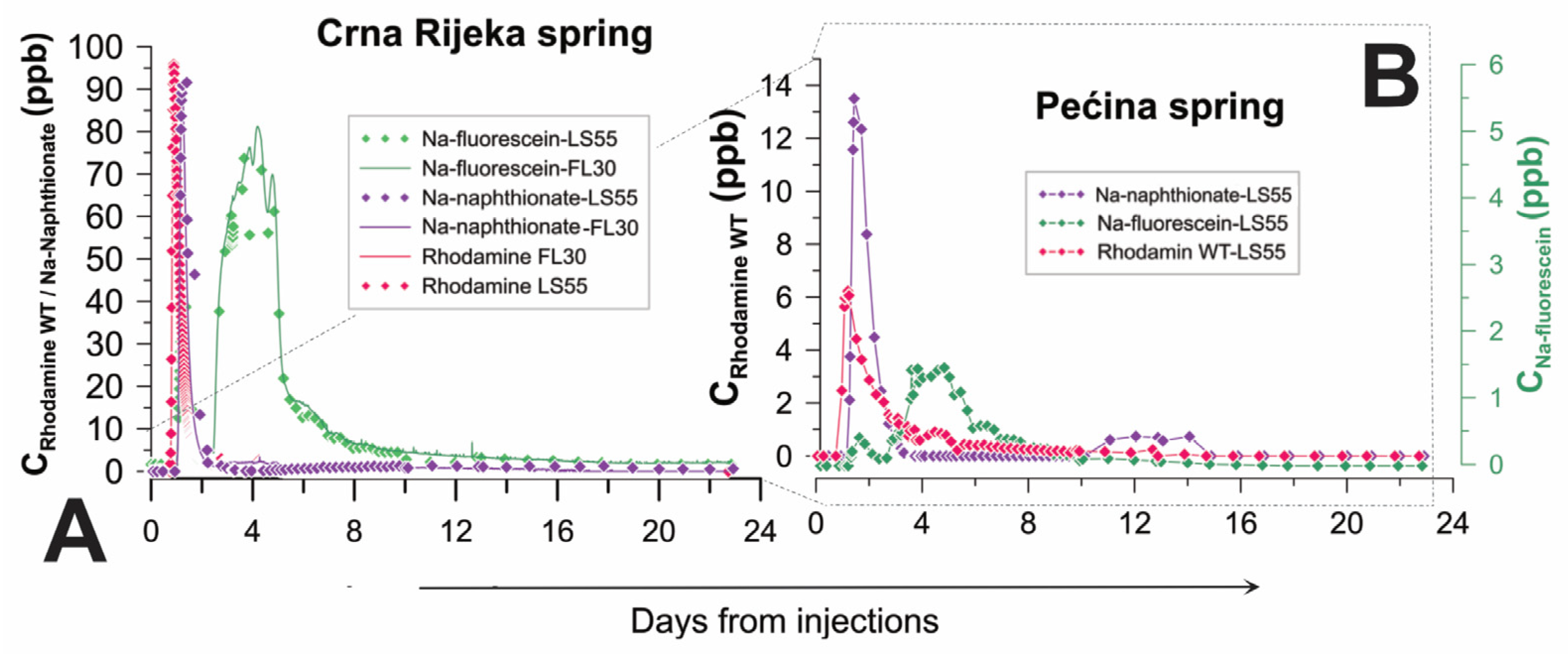

3.3. Tracer Test Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ford, D.; Williams, P. Karst Hydrogeology and Geomorphology; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider, N.; Drew, D. (Eds.) Methods in Karst Hydrogeology; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačič, G. Hydrogeological study of the Malenščica karst spring (SW Slovenia) by means of a time series analysis. Acta Carsologica 2010, 39, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroj, A.; Briški, M.; Oštrić, M. Study of Groundwater Flow Properties in a Karst System by Coupled Analysis of Diverse Environmental Tracers and Discharge Dynamics. Water 2020, 12, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironić, A.; Barešić, J.; Horvatinčić, N.; Brozinčević, A.; Vurnek, M.; Kapelj, S. Changes in the geochemical parameters of karst lakes over the past three decades—The case of Plitvice Lakes, Croatia. Appl. Geochem. 2017, 78, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Guo, F.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Milanović, S. Hydrogeological Responses of Karst Compartments to Meteorological Drought in Subtropical Monsoon Regions. J. Hydrol. 2025, 655, 132940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, B.; Ignjatović, S.; Smiljković, Ž.; Marinović, V.; Gajić, V. Epikarst of Eastern Part of Suva Planina Mt.: A New Perspective Defining from an Integrated Survey. Geol. Croat. 2025, 78, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, H.; Murillo, J.M. The effect of possible climate change on natural groundwater recharge based on a simple model: A study of four karstic aquifers in SE Spain. Environ. Geol. 2009, 57, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravbar, N.; Petrič, M.; Blatnik, M.; Švara, A. A Multi-Methodological Approach to Create Improved Indicators for the Adequate Karst Water Source Protection. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, A.; Pelletier, G.; Rodriguez, M.J. Using a Tracer to Identify Water Supply Zones in a Distribution Network. J. Water Supply Res. Technol. AQUA 2009, 58, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aley, T.; Osorno, T.C.; Devlin, J.F.; Goers, A. Practical Groundwater Tracing with Fluorescent Dyes; The Groundwater Project: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukač Reberski, J.; Marković, T.; Nakić, Z. Definition of the river Gacka springs subcatchment areas on the basis of hydrogeological parameters. Geol. Croat. 2013, 66, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C.A.J.; Postma, D. Geochemistry, Groundwater and Pollution; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; 536p. [Google Scholar]

- Radišić, M.; Rubinić, J.; Ružić, I.; Brozinčević, A. Hydrological System of the Plitvice Lakes—Trends and Changes in Water Levels, Inflows, and Losses. Hydrology 2021, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meaški, H. Model of the Karst Water Resources Protection on the Example of the Plitvice Lakes National Park. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2011; 211p. (In Croatian). [Google Scholar]

- Meaški, H.; Biondić, B.; Biondić, R. Delineation of the Plitvice Lakes karst catchment area, Croatia. In Karst Without Boundaries; Stevanović, Z., Krešić, N., Kukurić, N., Eds.; International Association of Hydrogeologists—Selected papers; CRC Press/Balkema: London, UK, 2016; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Vurnek, M.; Brozinčević, A.; Kepčija, R.; Matoničkin Frketić, T. Analyses of long-term trends in water quality data of the Plitvice Lakes National Park. Fundam. Appl. Limnol. 2021, 194, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dešković, I.; Marušić, R.; Pedišić, M.; Sipos, L.; Krga, M. Some Recent Results of Hydrochemical and Hydrological Investigations of Waters in the Plitvice Lakes Area. Vodoprivreda 1984, 16, 221–227. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Plitvice Lakes National Park Public Institution. Management Plan 2019–2028; Plitvice Lakes National Park: Plitvice Lakes, Croatia, 2019; Available online: https://np-plitvicka-jezera.hr/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Plitvice-Lakes-NP-Management-Plan.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Zaninović, K.; Srnec, L.; Perčec Tadić, M. Digital Annual Temperature Map of Croatia. Croat. Meteorol. J. 2004, 39, 51–58. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/67221 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Gajić-Čapka, M.; Perčec Tadić, M.; Patarčić, M. Digital Annual Precipitation Map of Croatia. Croat. Meteorol. J. 2003, 38, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Korbar, T. Orogenic Evolution of the External Dinarides in the NE Adriatic Region: A Model Constrained by Tectonostratigraphy of Upper Cretaceous to Paleogene Carbonates. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2009, 96, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahović, I.; Tišljar, J.; Velić, I.; Matičec, D. Evolution of the Adriatic Carbonate Platform: Palaeogeography, Main Events and Depositional Dynamics. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2005, 220, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polšak, A.; Juriša, M.; Šparica, M.; Šimunić, A. Basic Geological Map of Yugoslavia 1:100,000, Bihać Sheet (L33-116); Geološki zavod Zagreb, Savezni geološki zavod Beograd: Beograd, Serbia, 1976. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Velić, I.; Bahun, S.; Sokač, B.; Galović, I. Basic Geological Map of Yugoslavia 1:100,000, Otočac Sheet (L33-115); Geološki zavod Zagreb, Savezni geološki zavod Beograd: Beograd, Serbia, 1974. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Hydrological Programme. Hydrogeological Map of the Dinaric Karst Aquifer System. Available online: https://ihp-wins.unesco.org/dataset/hydrogeological-map-of-the-dinaric-karst-aquifer-system (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development. River Basin Management Plan 2022–2027; Official Gazette NN 156/2022; Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development: Zagreb, Croatia, 2022. (In Croatian)

- Piper, A.M. A graphic procedure in the geochemical interpretation of water-analyses. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1944, 25, 914–928. [Google Scholar]

- Selak, A.; Lukač Reberski, J.; Briški, M.; Selak, L. Hydrochemical characterization of a Dinaric karst catchment in relation to emerging organic contaminants. Geol. Croat. 2024, 77, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babinka, S. Multi-Tracer Study of Karst Waters and Lake Sediments in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina: Plitvice Lakes National Park and Bihać Area. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 2007; 168p. [Google Scholar]

- Dešković, I.; Pedišić, M.; Marušić, R.; Milenković, V. Importance, Purpose and Some Results of Hydrochemical, Hydrological and Sanitary Investigations of Surface and Groundwater in the Plitvice Lakes National Park. Vodoprivreda 1981, 12, 7–19. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Marušić, R.; Ćuruvija, M. Investigation of Subsurface Water Connections in the Plitvice Lakes National Park. Plitvički Bilt. 1990, 16, 19–28. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Šarin, A.; Singer, D. Report on the Spectrometric Analyses of Water Samples During the Dye Tracing of the Vranjkovac Estavelle Near Turjansko in 1988; Croatian Geological Survey: Zagreb, Croatia, 1989. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Biondić, B.; Goatti, V. Regional Hydrogeological Investigations of the Lika and Hrvatsko Primorje Regions; Croatian Geological Survey: Zagreb, Croatia, 1976. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuhta, M.; Frangen, T.; Stroj, A. Groundwater Investigation Works for the Protection of the Krbavica Spring, Phase II: Tracing of the Trnovac Field Ponor; Archive of the Croatian Geological Survey: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuhta, M.; Frangen, T. Tracing of the Šuputova Draga Ponor in the Homoljačko Field; Archive of the Croatian Geological Survey: Zagreb, Croatia, 2013. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuhta, M.; Brkić, Ž. Water Tracing Tests in the Dinaric Karst of Croatia. In Integrating Groundwater Science and Human Well-Being; Taniguchi, M., Yoshioka, R., Sinner, A., Aureli, A., Eds.; Proceedings CD; International Association of Hydrogeologists (IAH): Toyama, Japan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vasić, L.; Milanović, S.; Stevanović, Z.; Palcsu, L. Definition of groundwater genesis and circulation conditions of the complex hydrogeological karst system Mlava–Belosavac–Belosavac-2 (eastern Serbia). Carbonates Evaporite 2020, 35, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkar, A.; Brenčič, M. Spatio-temporal distribution of discharges in the Radovna River valley at low water conditions. Geologija 2015, 58, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Injection Point | Type of Tracer | Mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Uzelački Zavoj sinkhole | Na-naphthionate | 75 kg |

| Homoljac polje borehole | Na-fluorescein | 15 kg |

| Crna Kosa sinkhole | Rhodamine WT | 9 kg |

| Homoljac polje fissure | Rhodamine WT | 18 kg |

| Brezovac ponor | Na-naphthionate | 50 kg |

| Brezovac sinkhole | Na-fluorescein | 15 kg |

| Spring | T (°C) | pH | EC (μS/cm) | O2 (mg/L) | Ca2+ (mg/L) | Cl− (mg/L) | Na+ (mg/L) | NO3− (mg/L) | SO42− (mg/L) | HCO32− (mg/L) | Mg2+ (mg/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crna Rijeka | MIN | 7.00 | 7.6 | 384 | 9.09 | 56.11 | <5 | 0.93 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 281 | 8.7 |

| MAX | 11.70 | 8.5 | 472 | 11.89 | 98.67 | 7.3 | 4.6 | 0.97 | 4.01 | 356 | 34.8 | |

| AVERAGE | 8.87 | 8.14 | 413 | 10.57 | 79.98 | <5 | 1.73 | 0.72 | 1.43 | 311 | 18.6 | |

| Bijela Rijeka | MIN | 6.10 | 7.6 | 424 | 8.86 | 57.72 | <5 | 1.1 | 0.77 | 0.44 | 292 | 8.7 |

| MAX | 11.30 | 8.4 | 512 | 11.73 | 114.00 | 5.74 | 2.7 | 1.54 | 3.16 | 345 | 39.4 | |

| AVERAGE | 8.35 | 8.02 | 473 | 10.39 | 78.38 | <5 | 1.7 | 1.06 | 1.34 | 321 | 25.3 |

| IP | IT | TM (kg) | MS | D (m) | h (m) | t (h) | vmax (cm/s) | HC | L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BREZOVAC | Jadova Šepine ponor (758 m a.s.l.) | 17 November 1979 | N/A | Crna Rijeka | 5437 | 78 | 14–17 | 10.79 | High | [31] |

| Pećina | 6473 | 113 | 28 | 6.42 | water | |||||

| Pećine ponor (758 m a.s.l.) | 21 March 1980 | N/A | Crna Rijeka | 5390 | 78 | 30–36 | 4.99 | Moderate | [31] | |

| Pećina | 6152 | 113 | 46 | 3.72 | water | |||||

| Vrtovi sinkhole (~780 m a.s.l.) | 28 March 1981 | 20 | The tracer was retained in the subsurface | N/A | [18] | |||||

| Uzelački Zavoj sinkhole (780 m a.s.l.) | 7 May 1982 | 21 | Crna Rijeka | 5085 | 100 | 68 | 2.08 | N/A | [18] | |

| Pećina | 4780 | 135 | N/A | 1.95 | ||||||

| Near Bunar (780 m a.s.l.) | 13 May 1985 | N/A | The tracer was retained in the subsurface | N/A | [32] | |||||

| TURJAN and TRNAVAC | Vranjkovac estavelle (810 m a.s.l.) | 26 April 1988 | N/A | The tracer was retained in the subsurface | [33] | |||||

| Trnavac (724 m a.s.l.) | 30 March 2010 | 5 | Klanac | 16,060 | 273 | 140 | 3.18 | Moderate water | [35] | |

| Majerovo Vrelo | 17,709 | 277 | 164 | 3.00 | ||||||

| Tonkovića Vrilo | 16,060 | 278 | 153 | 2.9 | ||||||

| 23 April 2010 | 15 | Klanac | 16,060 | 213 | 296 | 1.51 | End of high water | [35] | ||

| Majerovo Vrilo | 17,709 | 264 | 312 | 1.58 | ||||||

| VRHOVINE | Vrhovine polje ponor (750 m a.s.l.) | 13 January 1975 | 50 | Zalužnica | 9700 | 227 | 306 | 0.88 | Low water | [34] |

| Sinac | 11,900 | 275 | 66 | 5.01 | ||||||

| Majeroveo Vrilo | 9900 | 273 | 30 | 9.17 | ||||||

| Klanac | 10,100 | 277 | 42 | 6.68 | ||||||

| Tonkovića Vrilo | 10,300 | 278 | 42 | 6.81 | ||||||

| HOMOLJAC polje | Šuputova Draga ponor (757 m a.s.l.) | 13 March 2013 | 75 | Tonkovića Vrilo | 17,930 | 302 | 114 | 4.39 | High water | [36] |

| Klanac | 17,920 | 301 | 114 | 4.38 | ||||||

| Majeroveo Vrilo | 19,320 | 297 | 138 | 3.9 | ||||||

| IP | IT | TM (kg) | MS | D (m) | h (m) | t1 (h) | vmax (cm/s) | cp (ppb) | tmaxc (h) | vp (cm/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 2023 | Crna Kosa sinkhole (843 m a.s.l.) | 22 Mar 2023 10:30 | Rhodamine WT 9 | Korenička Rijeka | 2382 | 145 | 244.2 | 0.27 | 44.267 | 270.2 | 0.24 |

| Homoljac polje borehole (792 m a.s.l) | 23 Mar 2023 8:30 | Na-fluorescein 15 | Korenička Rijeka | 2543 | 74 | 40.2 | 1.80 | 155.149 | 45.1 | 1.57 | |

| Mlinac | 2386 | 96 | 529.6 | 0.13 | 1.538 | 529.6 | 0.13 | ||||

| Uzelački Zavoj sinkhole (764 m a.s.l) | 23 Mar 2023 11:30 | Na-naphthionate 75 | Bijela Rijeka | 1313 | 46 | 35.1 | 1.07 | 791.410 | 54.1 | 0.67 | |

| Plitvički Ljeskovac * | 4237 | 91 | 51.3 | 2.34 | 47.215 | 90.1 | 1.31 | ||||

| Pećina * | 4730 | 117 | 52.4 | 2.56 | 19.387 | 74.9 | 1.75 | ||||

| April 2025 | Brezovac ponor (773 m a.s.l.) | 1 April 2025 11:25 | Na-naphthionate 50 | Crna Rijeka | 5683 | 103 | 23.8 | 6.62 | 91.580 | 29.3 | 5.38 |

| Pećina ** | 5560 | 126 | 30.3 | 5.09 | 13.499 | 34.4 | 4.49 | ||||

| Brezovac sinkhole | 1 April 2025 13:10 | Na-fluorescein 15 | Crna Rijeka | 4745 | 95 | 24.1 | 5.47 | 5.070 | 32.8 | 4.01 | |

| (765 m a.s.l.) | Pećina ** | 5026 | 118 | 31.7 | 4.41 | 1.409 | 116 | 1.21 | |||

| Homoljac polje fissure (763 m a.s.l.) | 1 April 2025 16:00 | Rhodamine WT 18 | Crna Rijeka | 6020 | 93 | 18.0 | 9.29 | 95.870 | 21.2 | 7.87 | |

| Pećina ** | 7588 | 116 | 23.3 | 9.04 | 6.230 | 29.83 | 7.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frangen, T.; Boljat, I.; Meaški, H.; Terzić, J. Delineation Using Multi-Tracer Tests and Hydrochemical Investigation of the Matica River Catchment at Plitvice Lakes, Croatia. Water 2025, 17, 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223261

Frangen T, Boljat I, Meaški H, Terzić J. Delineation Using Multi-Tracer Tests and Hydrochemical Investigation of the Matica River Catchment at Plitvice Lakes, Croatia. Water. 2025; 17(22):3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223261

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrangen, Tihomir, Ivana Boljat, Hrvoje Meaški, and Josip Terzić. 2025. "Delineation Using Multi-Tracer Tests and Hydrochemical Investigation of the Matica River Catchment at Plitvice Lakes, Croatia" Water 17, no. 22: 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223261

APA StyleFrangen, T., Boljat, I., Meaški, H., & Terzić, J. (2025). Delineation Using Multi-Tracer Tests and Hydrochemical Investigation of the Matica River Catchment at Plitvice Lakes, Croatia. Water, 17(22), 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223261