3.4.1. Analysis of Influencing Factors

The selection of driving factors for traditional villages must recognize their distinct nature compared with non-traditional settlements. While the latter are primarily shaped by contemporary socioeconomic forces, traditional villages embody a complex legacy of long-term human–environment interaction in which historical and cultural heritage plays a formative role. Building on this premise and integrating insights from foundational studies [

35,

36,

37], the analytical framework incorporates factors from three interrelated domains: environmental suitability, socioeconomic dynamics, and historical–cultural accumulation. This theoretical distinction is further substantiated by the contemporary socioeconomic realities of these villages. The economic livelihoods of communities in Shanxi’s traditional villages directly reflect their present-day functional dependencies. Shanxi Statistical Yearbook (2024) indicate that agriculture remains the principal livelihood, intrinsically linking these settlements to natural factors such as water availability and suitable terrain. Concurrently, the expansion of cultural tourism relies fundamentally on the historical–cultural heritage captured by the model. Therefore, to a considerable extent, the current economic functions and sustainability of traditional villages are not independent of but rather stem from the same foundational mechanisms that historically shaped their spatial distribution. This interdependence demonstrates that the analytical framework captures not only the historical genesis but also the ongoing vitality of these settlements.

These conceptual domains are translated into the following measurable variables:

The environmental factors included elevation, slope, aspect, average annual temperature, average annual precipitation, relative humidity, NDVI, and distance to rivers. The socioeconomic factors included distance to roads, population density, urbanization rate, per capita GDP, and distance to county-level administrative centers. The historical–cultural factor included ICH density (ICH_Den). These factors were designated as X1–X14. All spatial data were converted to the CGCS2000_3_Degree_GK_Zone_37 projected coordinate system and linked to 619 village points via spatial joins.

Table 3 presents the relationships between traditional villages and topographical factors. The average elevation of traditional villages was approximately 912 m, with an average slope of around 12.5°. Approximately 64.6% of traditional villages were situated at an elevation between 500 m and 1000 m, and 31.7% were located between 1000 m and 2000 m. This pattern aligns with the habitable elevation characteristics of settlements in the northern mountainous areas. Approximately 70.4% of traditional villages were located on slopes predominantly ranging from 5° to 35°. This siting pattern helps avoid both the flood risks associated with flat areas and the construction challenges arising from steep slopes. The numbers of traditional villages oriented toward the sunny side (90–270°) and the shady side (0–90°, 270–360°) across different aspects were nearly equal (ratio = 1 : 0.98), indicating no clear aspect preference in Shanxi Province.

Figure 4a–c show that most villages were located in areas with relatively high temperatures, abundant precipitation, and high humidity. The fitted curve further confirmed the positive association between village density and these climatic factors. Approximately 68.66% of the villages had an average annual temperature ranging from 10.5–13.5 °C. Additionally, about 92.25% of the villages had an average annual precipitation of 400 mm–700 mm, while nearly 96.45% had relative humidity exceeding 50%.

Figure 4d shows a nonlinear relationship between village density and distance to rivers, initially increasing and later decreasing. Nearly 70.8% of traditional villages were located within 3 km of a river, while only 9.7% were located more than 5 km away. This suggests that the distribution of traditional villages is highly dependent on water resources and people tend to settle near rivers.

Figure 4e shows that nearly 78.4% of traditional villages were located within 1 km of a road, while only 6.6% were situated more than 2 km away.

Figure 4f shows that nearly 88.9% of villages were located within 30 km of county-level administrative centers. These results suggest that traditional villages in Shanxi Province are generally located near roads and county-level administrative centers. The fitted relationships between the two factors and village density differed, with distance to roads exhibiting a U-shaped trend and distance to county-level administrative centers showing an inverted U-shaped trend. This may be attributed to transportation accessibility, resource exchange, and the radiating influence of the administrative centers [

38,

39].

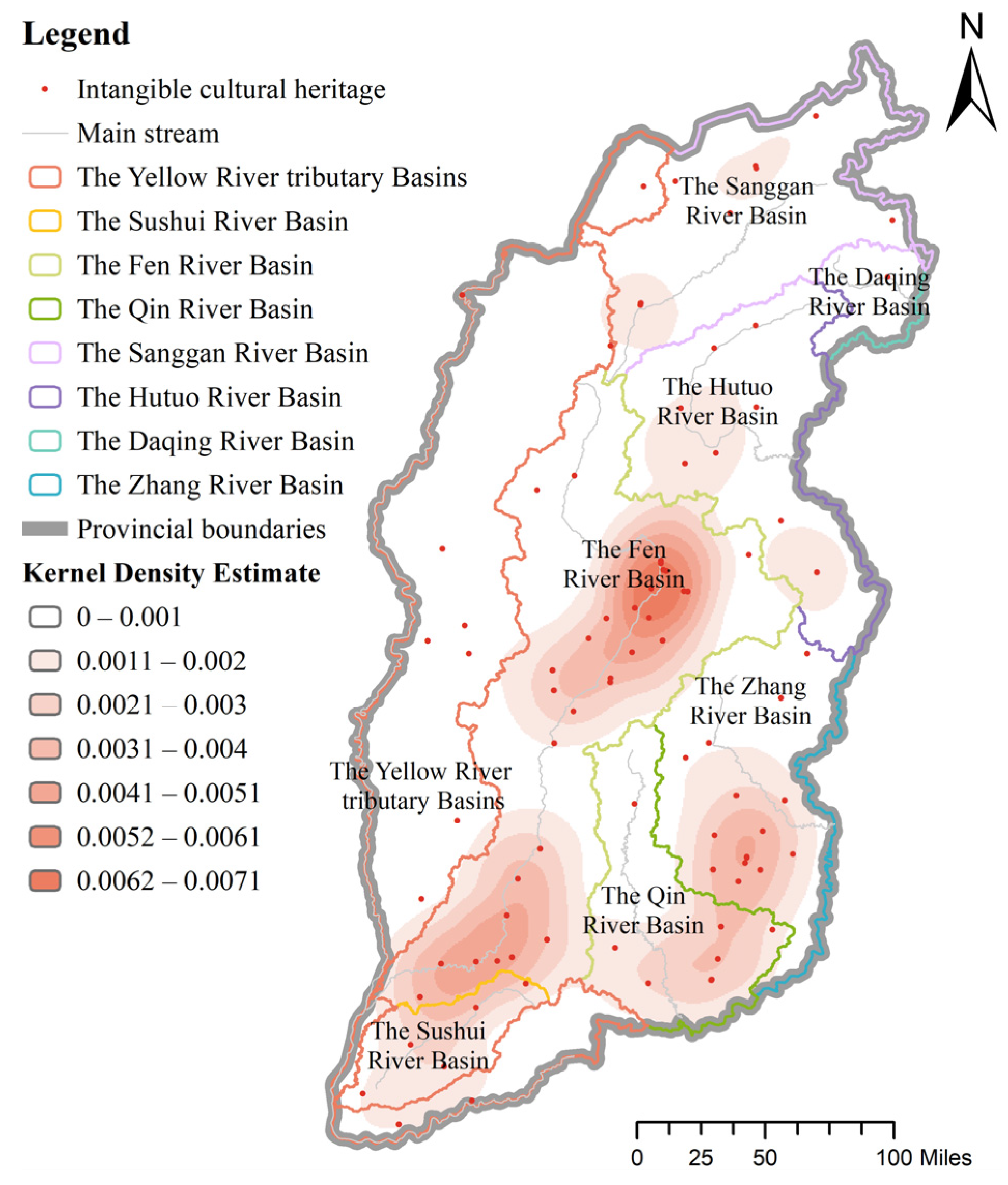

There was a significant spatial coupling between traditional villages and ICH. ICH was predominantly distributed in a belt-shaped pattern along the lower reaches of the Fen River Basin and the Qin River Basin, as well as the southern section of the Zhang River Basin (

Figure 5). In the middle and upper reaches of the Fen River Basin, ICH exhibited a core concentration pattern with a gradual outward diffusion. Areas of high ICH density overlapped with areas of high village density, indicating that villages constitute an essential foundation for the continuity of ICH [

40].

3.4.2. Driving Mechanisms of Spatial Heterogeneity in Traditional Villages

OPGD was applied to identify dominant factors, with the kernel density of traditional villages as the dependent variable and the aforementioned 14 factors as independent variables. The results indicated that all factors passed the 1% significance test except the aspect factor (

X3).

Figure 6a shows that, in the single-factor analysis, average annual precipitation (

X5,

q = 0.5332) exhibited the strongest explanatory power, followed by relative humidity (

X6,

q = 0.5258), and ICH density (

X14,

q = 0.5225). Environmental and historical–cultural factors demonstrated greater influence than socioeconomic factors.

Figure 6b shows that the two-factor interactions exhibited a significant positive synergistic effect, with the strongest interaction between average annual precipitation and ICH density (

q = 0.8352), followed by interactions between average annual precipitation and urbanization rate (

q = 0.7854) and between relative humidity and per capita GDP (

q = 0.7838).

Nine key factors (elevation, slope, average annual precipitation, relative humidity, distance to rivers, distance to roads, urbanization rate, distance to county-level administrative centers, and ICH density) were selected based on multicollinearity tests (VIF < 5). Subsequently, MGWR was applied to further explore the effects of these factors on the spatial heterogeneity of traditional villages.

Environmental factors constitute the fundamental constraints on the spatial distribution of traditional villages.

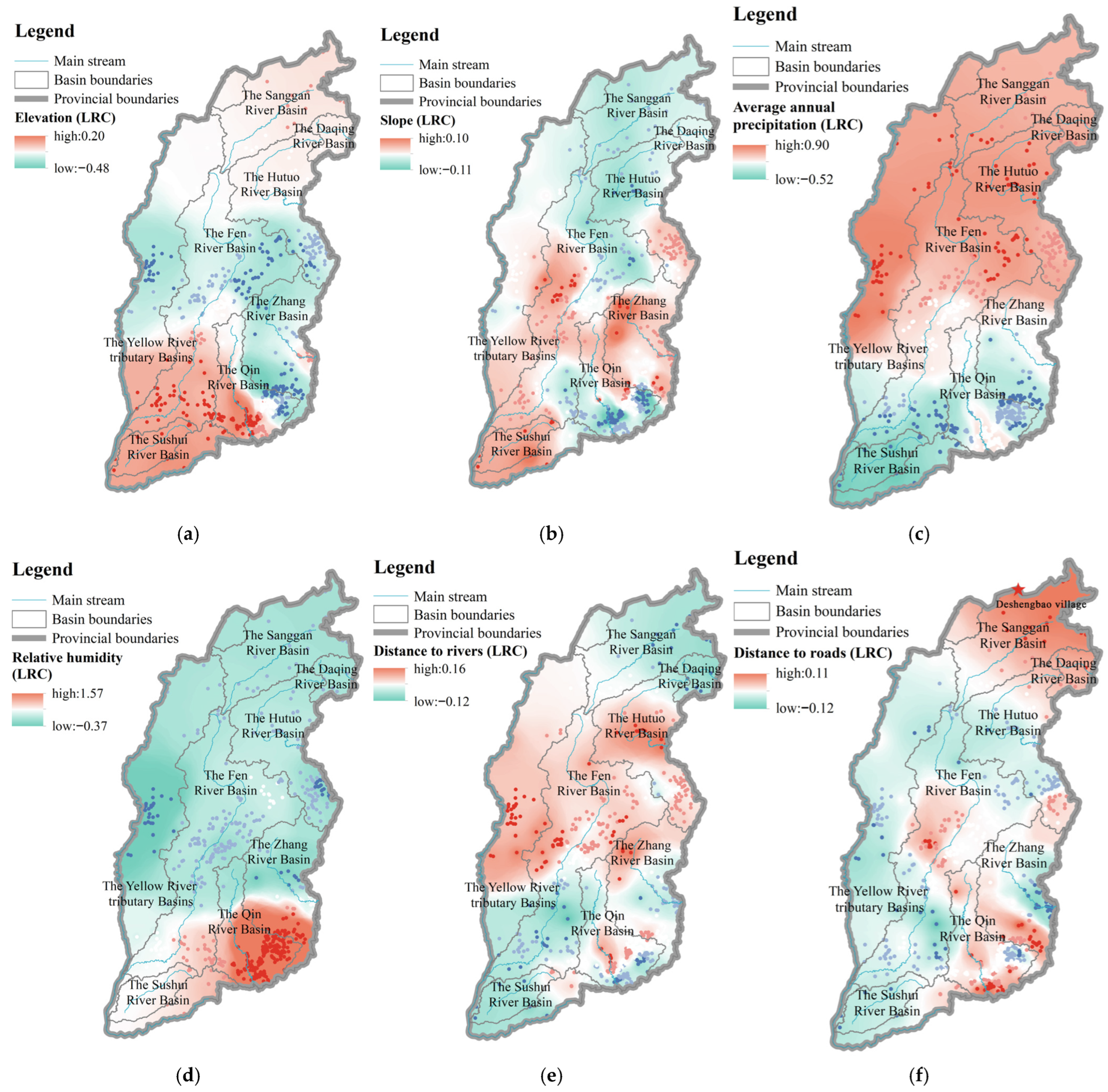

Table 4 reveals that 22.1% of the LRCs for elevation were positive, while 64.6% of all coefficients were significant (

p < 0.05), suggesting a clear negative relationship (

Figure 7a). The direction was determined by the dominant sign of the LRCs, and the strength was measured by the proportion of statistically significant coefficients. High positive LRCs values were mainly concentrated in the middle and lower reaches of the Fen and Qin River Basins, as well as in the lower reaches of the Yellow River tributary Basins. Shanxi Province is situated on the Loess Plateau, with an average elevation of approximately 1100 m. Villages are predominantly distributed across plains, terraces, and low- to mid-elevation hills. These areas feature flat terrain and fertile soil, providing favorable conditions for agricultural production and supporting the stable settlement of large populations. High-altitude areas can provide natural isolation for villages, reducing the impacts of warfare and modern development. However, such areas are also prone to soil erosion and landslides. In addition, cold climatic conditions and limited transportation access are unfavorable for the long-term development of villages.

For slope,

Figure 7b shows that 41.4% of the LRCs were positive, and only 2.4% of all coefficients were significant, indicating a slight negative effect. High positive values were mainly concentrated in the northern section of the Zhang River Basin, the middle reaches of the Fen River Basin, and the upper reaches of the Qin River Basin. Lower slopes facilitate agricultural cultivation and reduce transportation costs, but are more vulnerable to flooding. Excessive slopes increase the difficulty and cost of farmland cultivation and disrupt the continuity of road networks, which hinder the long-term development of villages [

41]. The overall weak influence of slope, despite the mountainous setting of the Loess Plateau, suggests that traditional villages predominantly utilized and were constrained by the limited extent of gentle terrain within the major river basins, rather than the steep slopes themselves.

Figure 7c shows that 75.1% of the LRCs for average annual precipitation were positive, and 52.5% of all coefficients were significant, indicating a pronounced positive effect. High positive values were continuously concentrated in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River tributary Basins, the upper reaches of the Fen River Basin, and the northern section of the Hutuo River Basin. This pattern underscores that precipitation was not merely a background condition but the critical determinant for the viability of rain-fed agriculture, the historical economic foundation across the Loess Plateau. In these areas, the increase in village density directly tracks the gradient of water availability [

42]. The distribution reflects a profound adaptation to a semi-arid environment, where communities clustered most densely in these sub-basins that reached the necessary threshold for sustaining stable dry-land farming. While settling near permanent water bodies was ideal, the widespread reliance on precipitation itself shaped a distinct “precipitation-centric” settlement logic, differentiating it from regions where river water was the sole primary source. Consequently, the extremities of precipitation did not just constrain distribution but actively defined the fertile band within the river basins where traditional village life could flourish.

Figure 7d shows that 72.4% of the LRCs for relative humidity were positive, and 6.0% of all coefficients were significant, indicating a weak positive effect. In the middle and lower reaches of the Qin River Basin and the southern section of the Zhang River Basin, increases in relative humidity were significantly associated with higher village density. Within the arid to semi-arid context of the Loess Plateau, humidity acted not as a primary driver but as a critical secondary buffer. Its positive influence is most intelligible in synergy with other factors: in these specific basins, adequate humidity mitigated the chronic risk of loess drying and cracking, directly enhancing the durability of the earth architecture that defines these villages’ material heritage. Furthermore, it supported a more reliable micro-climate for agriculture by reducing soil moisture evaporation. Thus, while seldom the sole reason for settlement, localized humidity provided a decisive comparative advantage by reducing environmental stress on both the built structures and the farmlands that sustained the community, explaining its subtle but spatially concentrated positive role.

Figure 7e illustrates that 69.5% of the LRCs for distance to rivers were positive, and 25.0% of all coefficients were significant, indicating a moderate positive effect. High positive values were clustered in the middle reaches of the Yellow River tributary Basins, the middle and upper reaches of the Fen River Basin, the Hutuo River Basin, the northern section of the Zhang River Basin, and the middle and lower reaches of the Qin River Basin. This pattern reveals a sophisticated settlement strategy that transcends a simplistic “water-centric” narrative and enters the realm of risk management. The preliminary quantitative analysis demonstrates a nonlinear relationship: village density peaks not immediately adjacent to rivers, but within a “sweet spot” of approximately 2–5 km. This optimal band, also reflected in the clustered high LRCs values across multiple basins, allowed settlements to maintain accessible proximity for irrigation and domestic use while strategically mitigating the dual threats of flooding and historical military conflicts that plagued immediately riparian zones [

43]. Thus, the “moderate positive effect” of distance does not contradict the importance of water; rather, it quantifies the intentional offset that balanced resource access with long-term safety. This nuanced trade-off represents a core principle of traditional human–environment adaptation on the Loess Plateau, where villages were positioned not at the water’s edge, but within its “sphere of influence” yet beyond its “zone of immediate danger”.

Socioeconomic factors are external drivers of the spatial distribution of traditional villages.

Figure 7f shows that the positive LRCs for distance to roads accounted for 30.9%, and the proportion of significant coefficients was 17.8%, indicating a moderate negative effect. High positive values were mainly clustered in the northern section of the Sanggan River Basin, with some scattered across the middle reaches of the Fen River Basin, the lower reaches of the Qin River Basin, and the southern section of the Zhang River Basin. These areas prospered along ancient transportation routes such as the Shanxi Merchants’ Road, the Eight Xings of the Taihang Mountains, and the Ming–Qing post roads [

44]. In the northern Sanggan River Basin, a region shaped by historic trade routes, modern road access reinforces path-dependent prosperity, as exemplified by Deshengbao Village’s success in cultural tourism. However, the significant negative coefficients concentrated in the lower Qin River Basin uncover a more concerning dynamic: improved connectivity serves as a direct conduit for cultural homogenization. Here, roads facilitate not only the inflow of tourists but also of external cultural models and construction materials, which systematically supplant local vernacular styles and fragment traditional landscapes. This process directly threatens the cultural distinctiveness that underpins both the identity and sustainability of these villages.

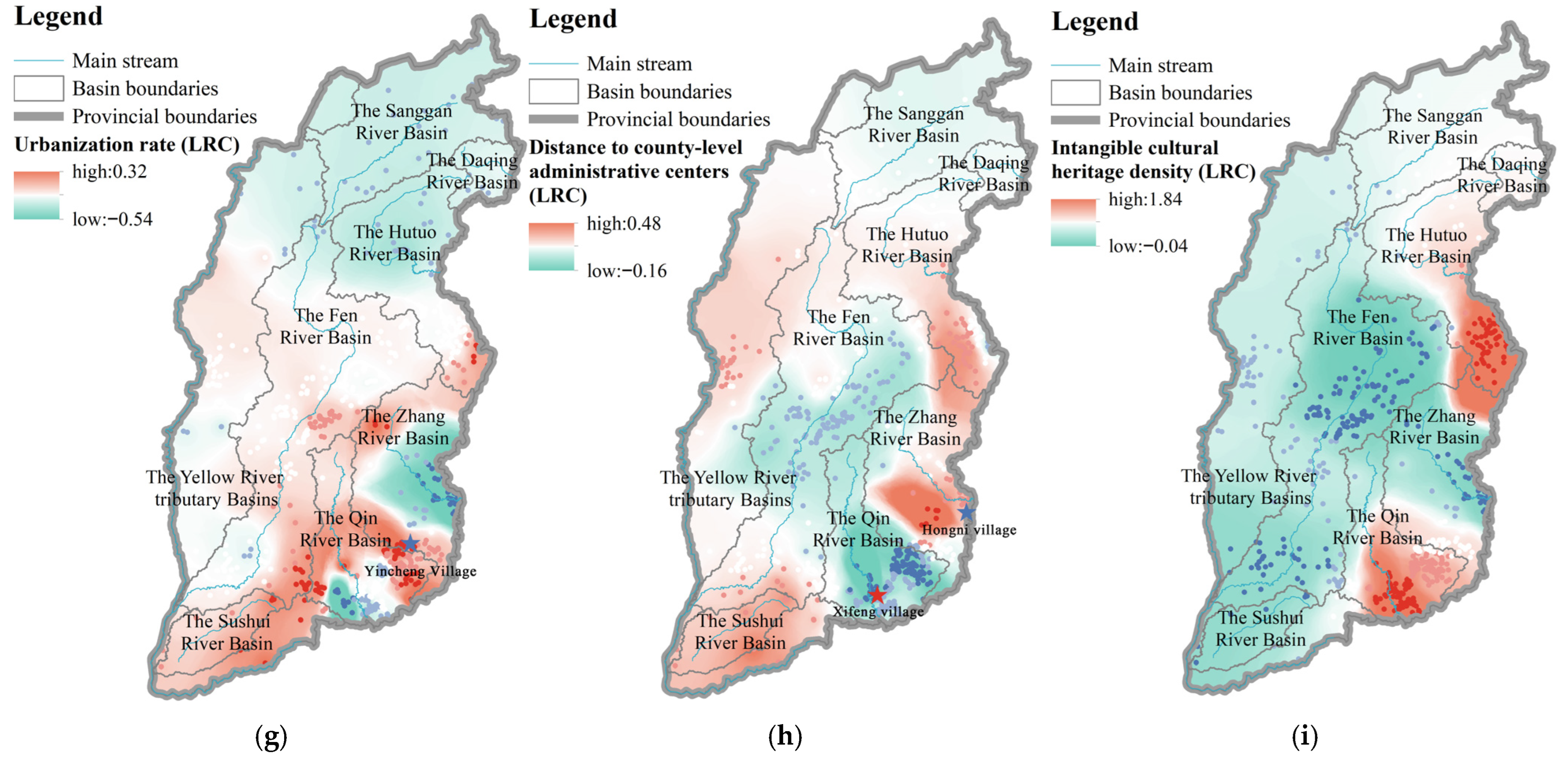

Figure 7g shows that the positive LRCs for urbanization rate was 37.0%, and the proportion of significant coefficients was 22.5%, indicating an overall negative effect. High positive values were observed in tourism-oriented villages in the middle and lower reaches of the Qin River Basin and the northern and middle sections of the Zhang River Basin. In tourism hubs like Yincheng ancient town in Changzhi City, urbanization provides vital infrastructure and markets. Yet, beyond these clusters, its predominant effect is one of systemic hollowing out. The significant negative coefficients demonstrate that urban expansion acts as a powerful siphon, drawing away the younger generation and destabilizing local economies [

45,

46,

47]. This exodus severs the intergenerational transmission of ICH and erodes the social fabric, leading to a critical loss of custodians for both tangible and intangible heritage. The sustainability threat here is not merely physical encroachment, but the collapse of the socio-cultural community itself.

Figure 7h shows that the positive LRCs for distance to county-level administrative centers accounted for 70.5%, and the proportion of significant coefficients was 50.7%, indicating a marked positive effect. The southern section of the Zhang River Basin was a cluster of high positive values, while the lower reaches of the Qin River Basin form a cluster of high negative values. This pattern highlights a paradox of proximity. In remote areas like Hongni Village, distance provides a natural buffer, preserving heritage from direct development pressure. Conversely, villages like Xifeng Village in the Qin River Basin epitomize a “policy shadow” effect. Situated at an intermediate distance, they are too close to avoid resource drain to urban centers, yet too peripheral to attract targeted conservation investments or effective policy support. This institutional marginalization results in physical decay and population decline, not due to a lack of heritage value, but because of a systemic failure in the allocation of preservation resources, posing a fundamental threat to their long-term persistence [

48].

Historical–cultural factors are intrinsic drivers of the spatial distribution of traditional villages.

Figure 7i shows that the positive LRCs for ICH density accounted for 95.0%, and the proportion of significant coefficients was 89.8%, indicating a strong positive effect. Two clusters of high positive values were evident in the middle and lower reaches of the Qin River Basin and the southern section of the Hutuo River Basin. Traditional villages serve as both the tangible carriers and communication platforms of ICH, while ICH enriches these villages with profound cultural connotations [

49]. This finding is exemplified by Dayang Town in the middle Qin River Basin, where the ICH of traditional handmade needle-making is actively revitalized. Here, the preserved Ming–Qing street pattern and courtyards are not mere relics but functional spaces for workshops and cultural performances. This synergy between tangible heritage and ICH practice demonstrates a core mechanism for sustainability: it transforms cultural assets into the foundation for a tourism-oriented economy, directly generating livelihoods and ensuring the community’s ongoing role as a cultural custodian.