1. Introduction

The contamination of marine environments with heavy metals poses significant environmental and health challenges. These metals, often released from anthropogenic sources near the land surface, can accumulate in marine organisms. This accumulation, in turn, may cause adverse effects on both aquatic life and human health, through direct exposure as well as indirectly, via the food chain [

1,

2,

3].

After being released into the water environment, soluble heavy metals undergo immobilization and deposition on sediments through mechanisms like adsorption by ion exchange, coagulation with dissolved or suspended species and precipitation as insoluble compounds. The salinity of seawater promotes suspended particle aggregation, accelerating heavy metals sedimentation. As a result, sediments act as reservoirs, adsorbing, accumulating, and, once the environmental or physicochemical conditions change (e.g., pH, Eh, and dissolved oxygen, etc.), potentially releasing heavy metals into surrounding marine water [

3,

4].

Consequently, developing effective remediation strategies for contaminated sediments is essential to preserve the marine environment.

Sediment remediation techniques can be broadly classified into ex situ and in situ processes. The former involves dredging contaminated sediments and treating them through chemical, physical, or biological processes in specialized reactors. While this approach effectively removes mobile metals, it is costly and can disrupt sediment structure and ecosystem, limiting its large-scale application. On the other hand, in situ remediation primarily focuses on stabilizing heavy metals within the sediment by enhancing their sorption, precipitation, or complexation. These methods are cost-effective, as they do not require sediment removal, but they do not reduce the total metal content and, consequently, under certain conditions, immobilized metals may be remobilized into the water [

5]. The main advantage of in situ methods is their simpler implementation, requiring only the addition of amendments to the sediment.

Various in situ remediation techniques have been developed for the treatment of contaminated sediments, each characterized by specific mechanisms of action, advantages, and limitations. Physico-chemical methods, such as solidification/stabilization and sediment flushing, enable contaminant immobilization or facilitate metal recovery. However, their effectiveness may be constrained by factors including sediment depth, heterogeneity, and potential alterations in the physico-chemical properties of the sediments [

6]. Electrokinetic separation is a physical technique, which offers operational simplicity and minimal by-product generation, with the added benefit of potential metal recovery. Nevertheless, its performance may be significantly influenced by pH fluctuations, sediment microstructure, and the requirement for additional treatment steps to achieve satisfactory removal of heavy metals [

7,

8]. Bioremediation represents a low-impact and straightforward biological alternative, although its applicability is typically limited to low-risk sites due to slower kinetics and a higher sensitivity to climatic and geological conditions [

9]. Capping and active capping are widely adopted for their cost-effectiveness and environmental compatibility. These approaches are still associated with several technical limitations, including the loss of cap integrity under high hydrodynamic conditions, risk of contaminant breakthrough, and unsuitability in shallow or ecologically sensitive environments [

10].

Further, the reactive materials used in the active capping aim to prevent contaminant remobilization not only via physical sequestration—as in conventional capping—but also via adsorption or degradation processes. These processes target both dissolved and weakly adsorbed contaminants, which are released in the aqueous phase and subsequently transferred onto the adsorbent. The possibility of relying on such mechanisms allows for a reduction in the capping layer thickness. Nonetheless, the long-term stability of the active capping may represent a challenge, especially in the marine environment, where several factors may account for the remobilization of the adsorbed contaminant. In this regard, although the recovery of the capping material should be considered, the type of reactive material used may play a role in determining the overall sustainability of this technique, as highlighted by Todaro et al. [

11].

Several recent studies have explored the use of waste-derived materials for remediation by active capping of metal-contaminated sediments. This approach not only addresses the issue of waste management circularity but also provides a sustainable solution for pollutant removal.

Industrial slags, for instance, have been widely explored due to their alkaline nature and ability to immobilize metals. In particular, Park et al. [

12] demonstrated that steel slag applied as a capping material over artificially contaminated sediments in saline conditions was highly effective in preventing the release of several heavy metals into the overlying water. Similarly, Kutuniva et al. [

13] assessed alkali-activated blast furnace slag as a sediment amendment, showing that it reduced the mobility of multiple contaminants in non-saline water, although its efficiency varied among different metals, with some (e.g., Cr) remaining less effectively immobilized. These studies underline the potential of industrial by-products for sediment remediation, but also highlight challenges related to their performance across a wide spectrum of contaminants and environmental conditions.

More recently, biochar has gained attention as a capping material, particularly due to its origin from renewable feedstocks. For example, Wang et al. [

14] tested biochar derived from Enteromorpha under saline conditions, reporting removal efficiencies for Pb and Cd that increased with the applied layer thickness. Despite these promising results, performance remained partial and dependent on experimental conditions, pointing to the need for more efficient and adaptable sorbent systems.

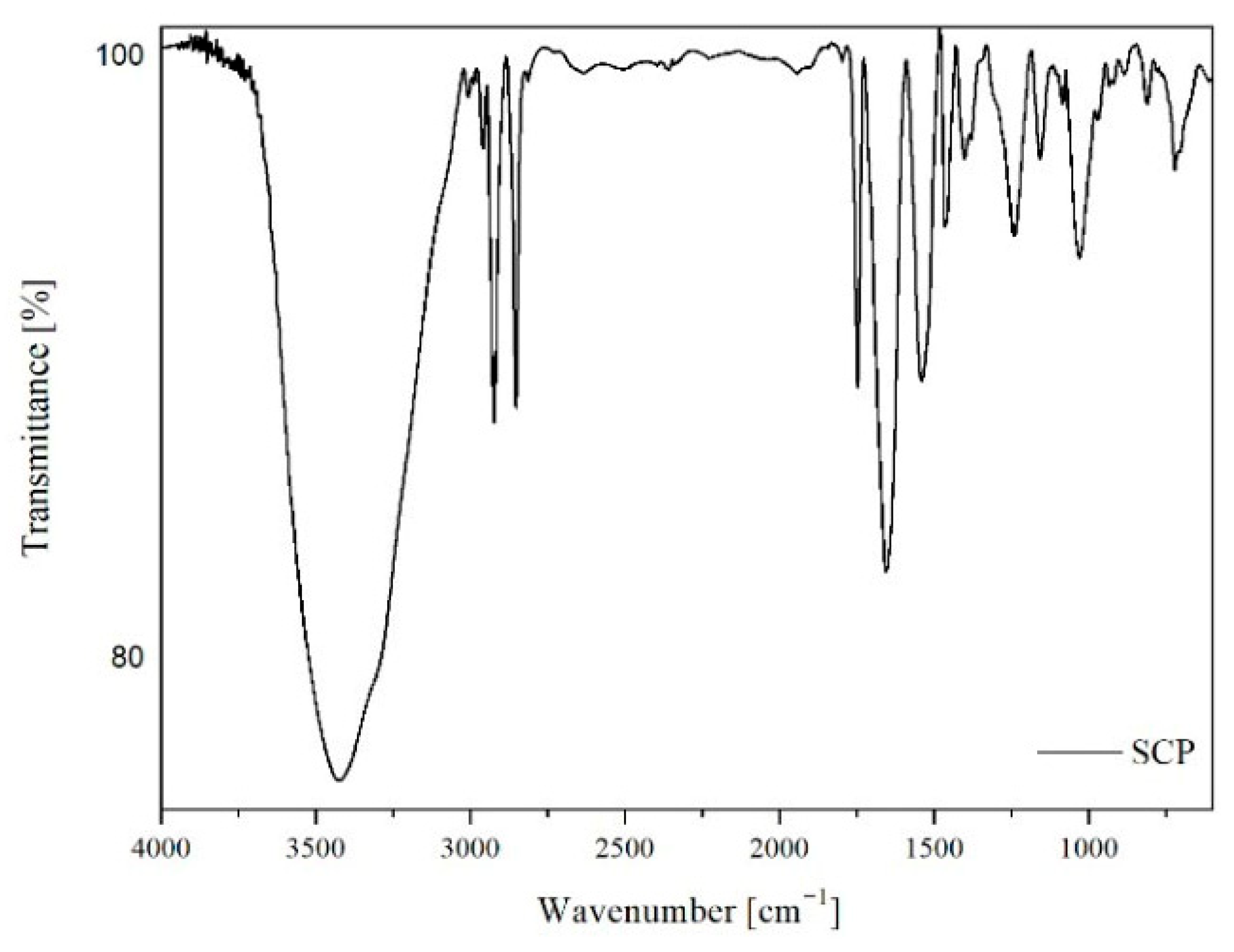

Among non-conventional absorbents which may still be produced from waste substrates, proteins offer a series of interesting properties. Due to their structure, proteins can work as universal molecular adhesives, as they are highly effective in binding a broad range of contaminants in water and making them an ideal and sustainable material for this purpose [

15]. For instance, the complex chemistry of whey proteins determines their natural affinity to heavy metals ions [

16]. In this context, single-cell proteins (SCPs) hold a great potential. They consist of microbial biomass or protein extracts derived from microorganisms such as bacteria, yeasts, fungi, and microalgae that contain more than 30% protein in their biomass [

17]. The production of SCPs using low-cost waste materials from the food and beverage industries, as well as directly from agricultural and forestry resources, is increasingly being explored [

17]. This approach utilizes waste substrates such as sugarcane bagasse [

18], brewery spent grains, hemicellulose hydrolysate [

19], whey [

20,

21], and other common food industry by-products, including orange and potato residues, molasses, and malt spent rootlets [

19], offering a sustainable and cost-effective solution for SCP production.

Previous studies have provided valuable insights into the adsorption performance of proteins and protein-based materials for the removal of heavy metal ions. In particular, Pomastowski et al. [

22] showed that casein can effectively adsorb zinc from aqueous solution, while Buszewski et al. [

23] confirmed the potential of β-lactoglobulin for Zn removal. For chromium, Peydayesh et al. [

24] and Ramírez-Rodríguez et al. [

25] reported that protein fibrils obtained from whey proteins were able to retain significant amounts of the contaminant. Although these results are encouraging, most of the existing studies focus on isolated proteins or protein fibrils, tested under controlled laboratory conditions, typically in freshwater and with relatively simple contaminant matrices.

All these studies were carried out in single metal water solutions, as they mainly aimed to propose the use of those novel adsorbents for the treatment of contaminated water. Conversely, the potential of protein-based adsorbent for heavy metal adsorption in seawater has not been evaluated yet.

Taken together, these findings emphasize both the potential and the limitations of current approaches. Industrial by-products such as slags may be efficient in some cases but face challenges in terms of selectivity and long-term stability, while biochar offers versatility but often only achieves partial immobilization under saline conditions. Protein-based adsorbents show excellent affinity for specific metals but have so far been studied mainly in purified forms and not as part of complex biomasses. This leaves an open research space for the development of protein-rich, waste-derived sorbents, such as microbial single-cell proteins, tested in realistic saline environments and under multi-contamination scenarios. By addressing these gaps, such materials could simultaneously advance sustainable waste valorization and provide effective solutions for the remediation of contaminated marine systems.

Moreover, seawater presents a unique and complex matrix, characterized by high salinity and the presence of competing ions [

26]. These factors can significantly influence the adsorption behavior of heavy metals mechanism [

27], necessitating a thorough investigation to assess the performance of the adsorbent material under marine conditions.

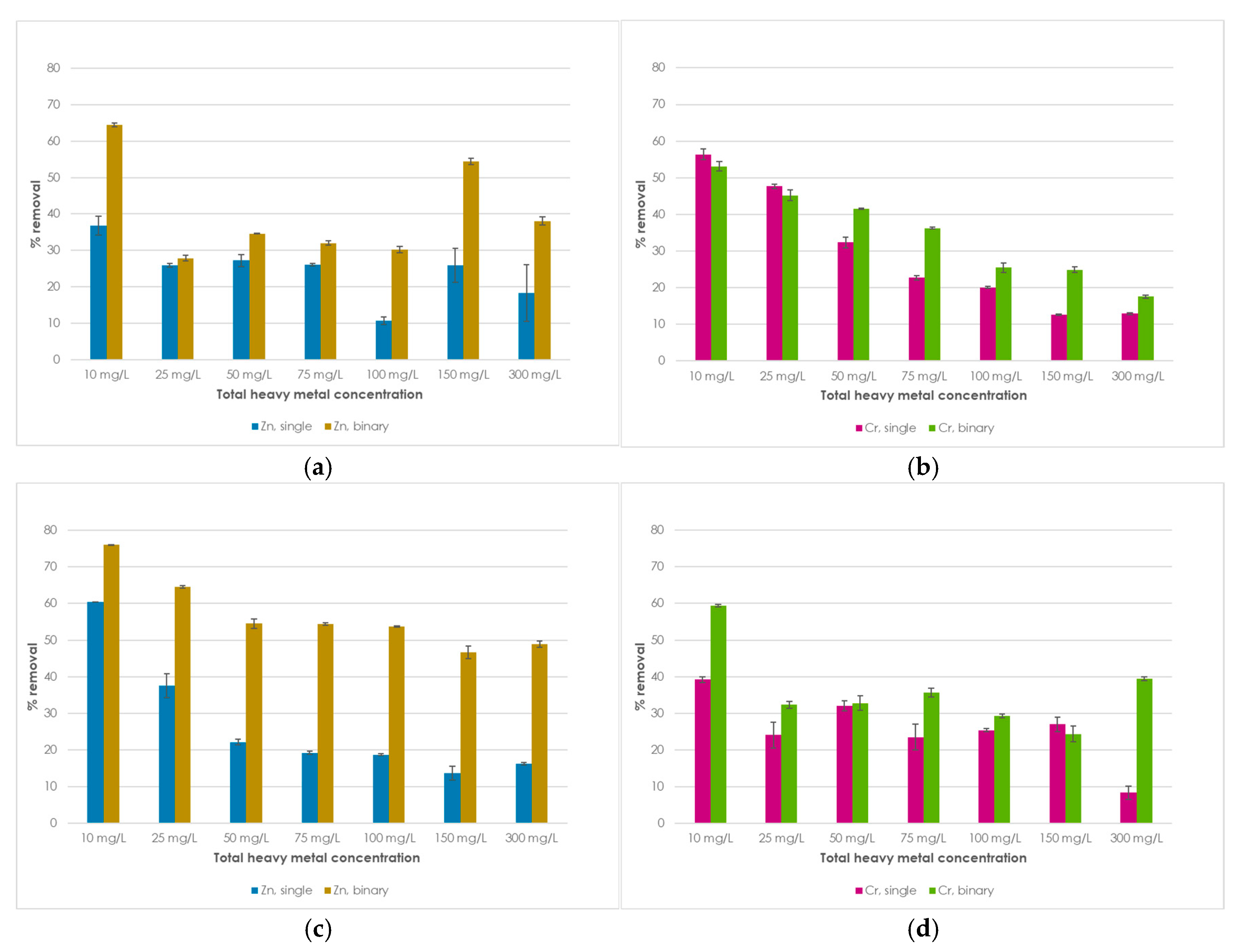

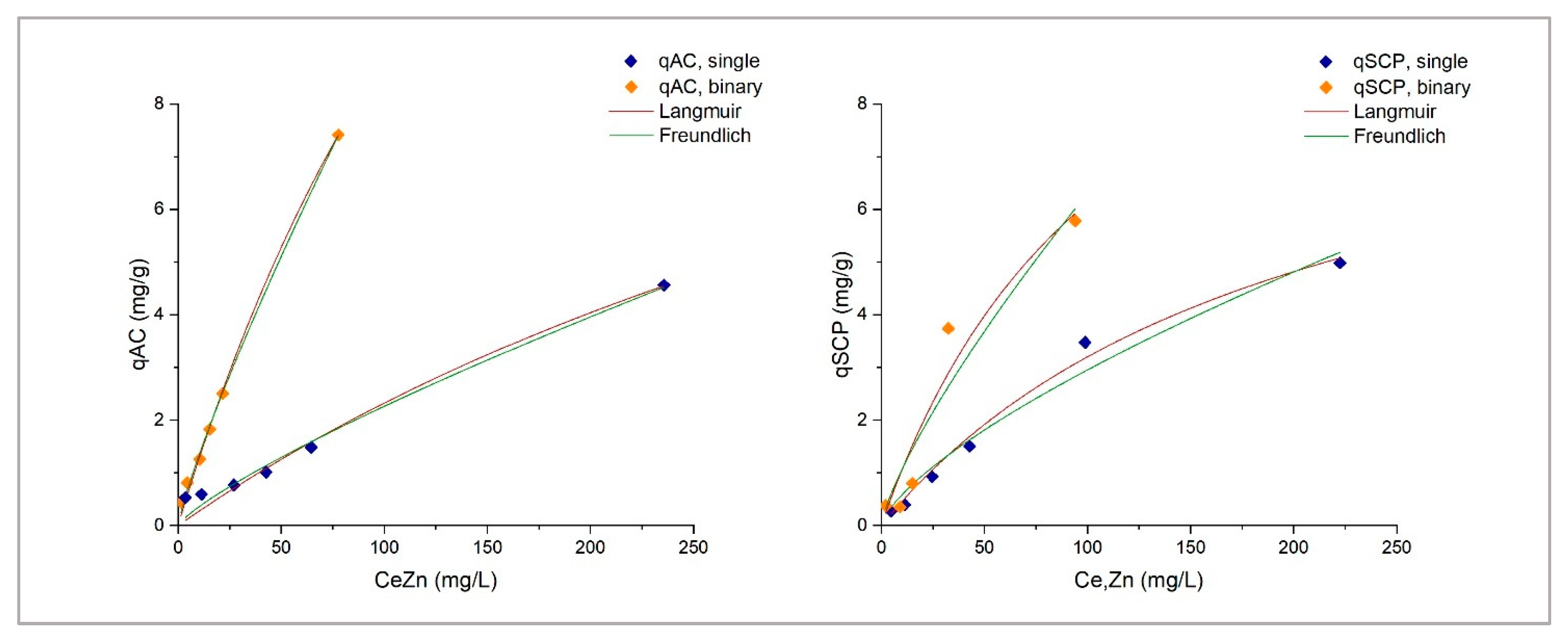

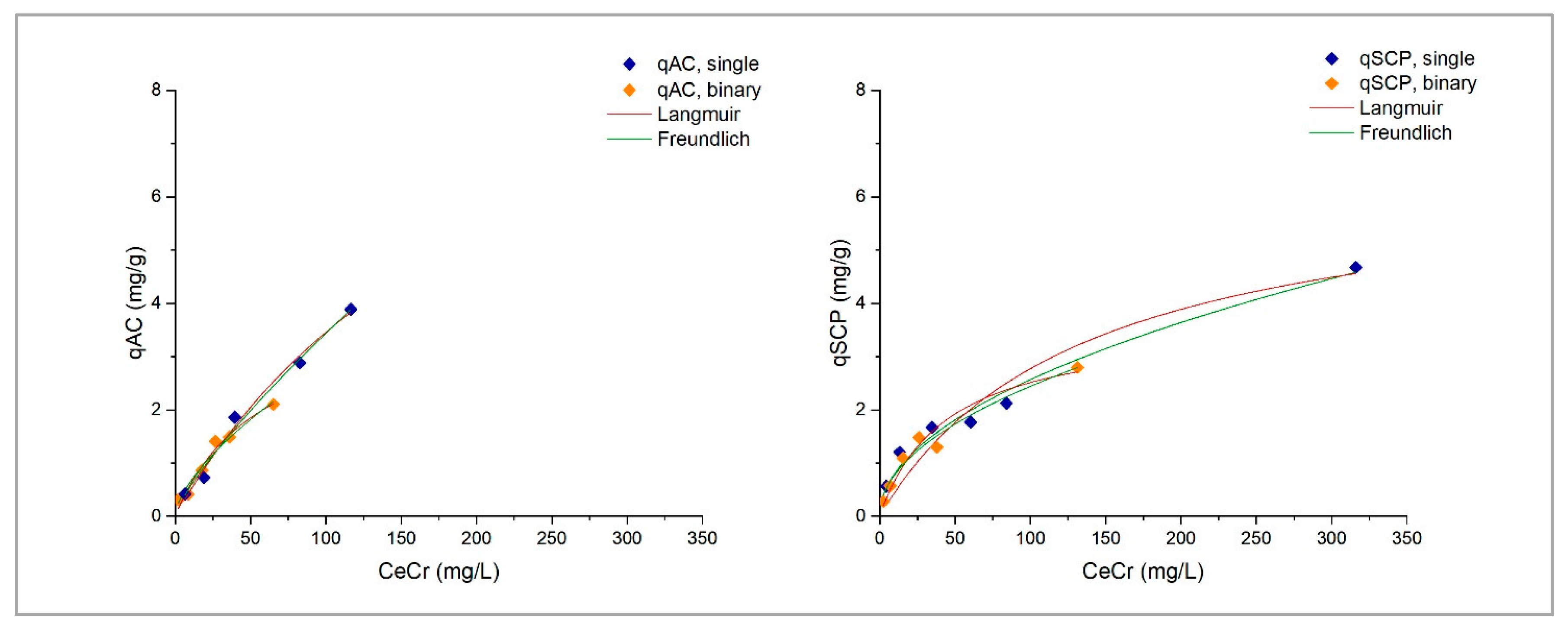

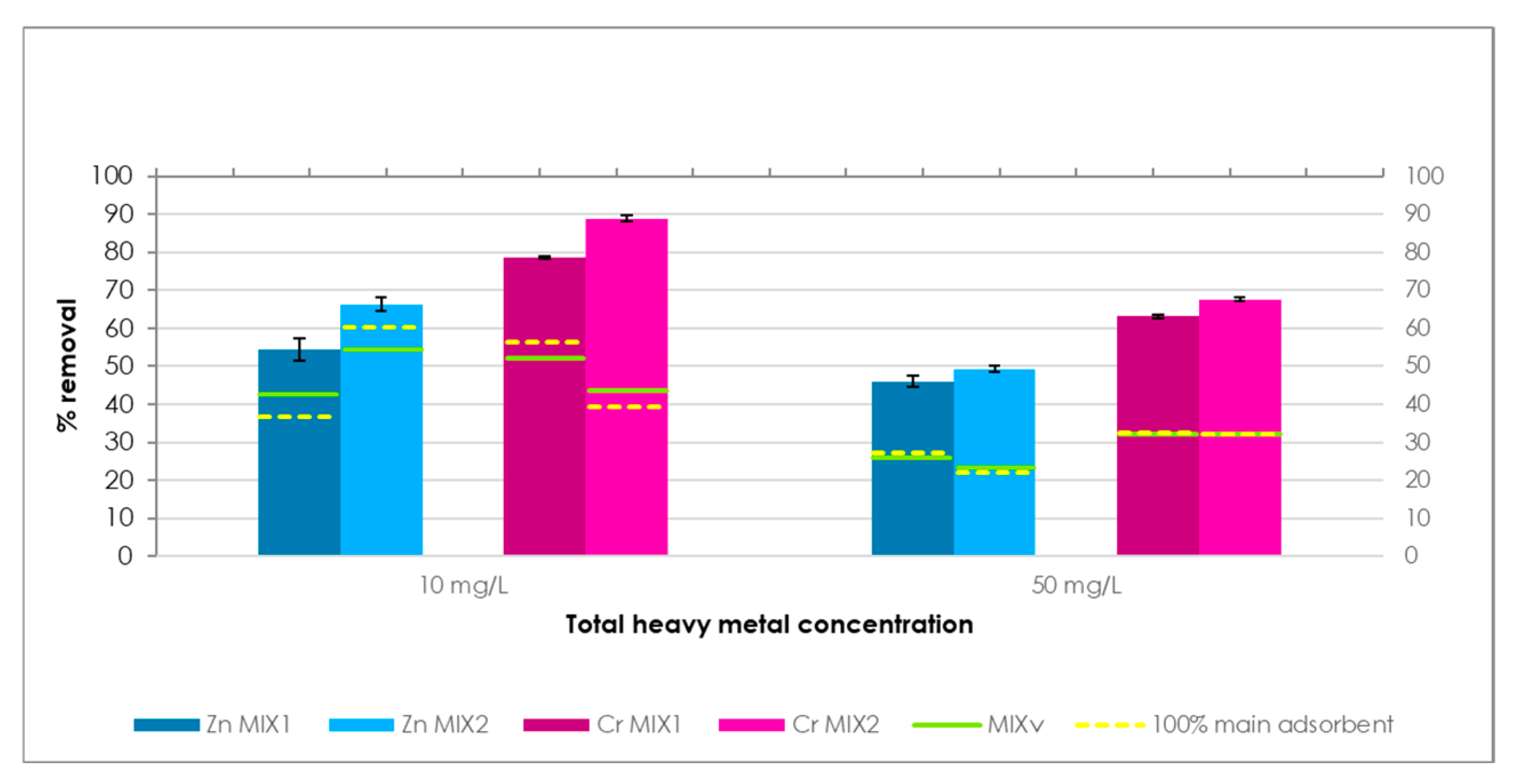

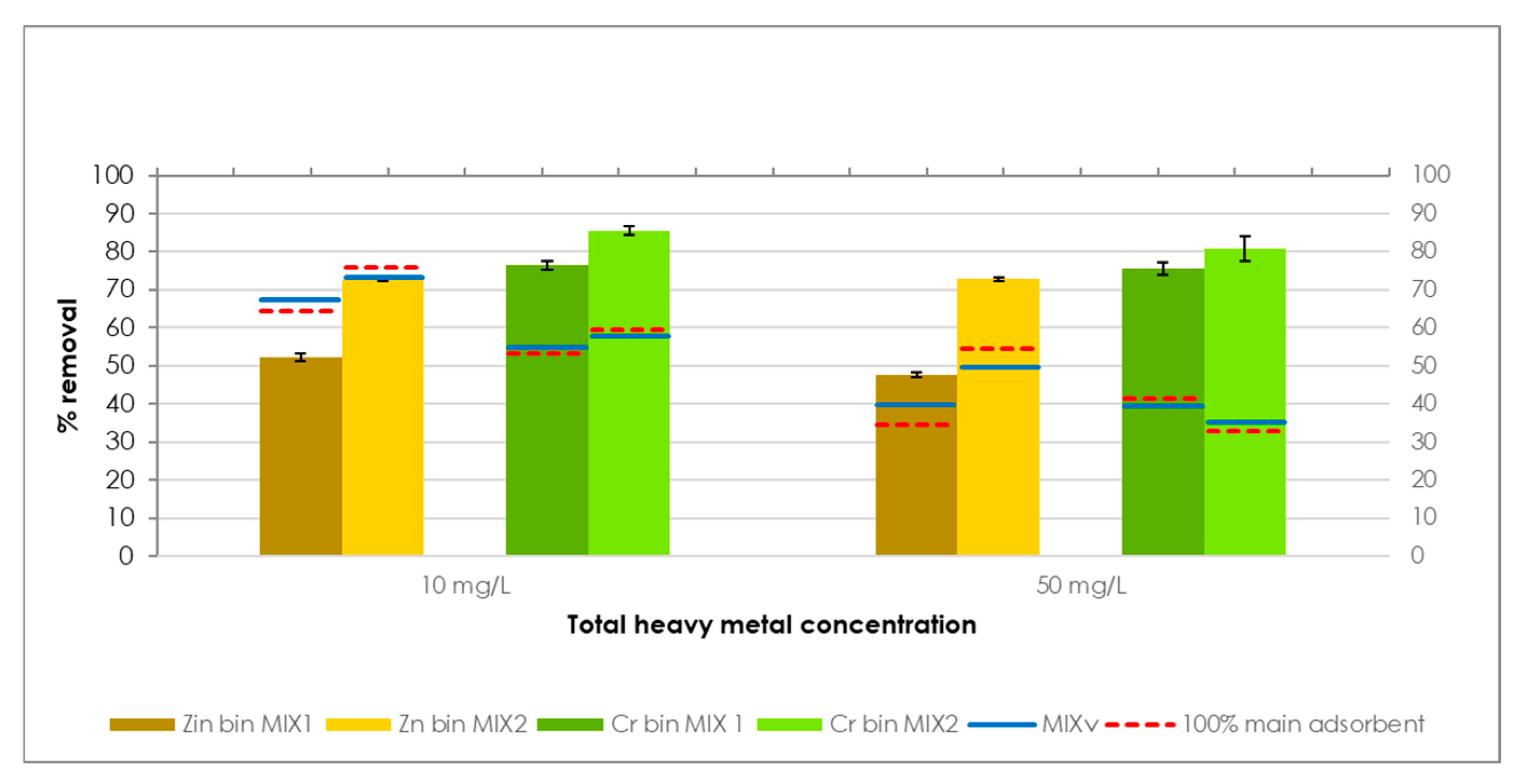

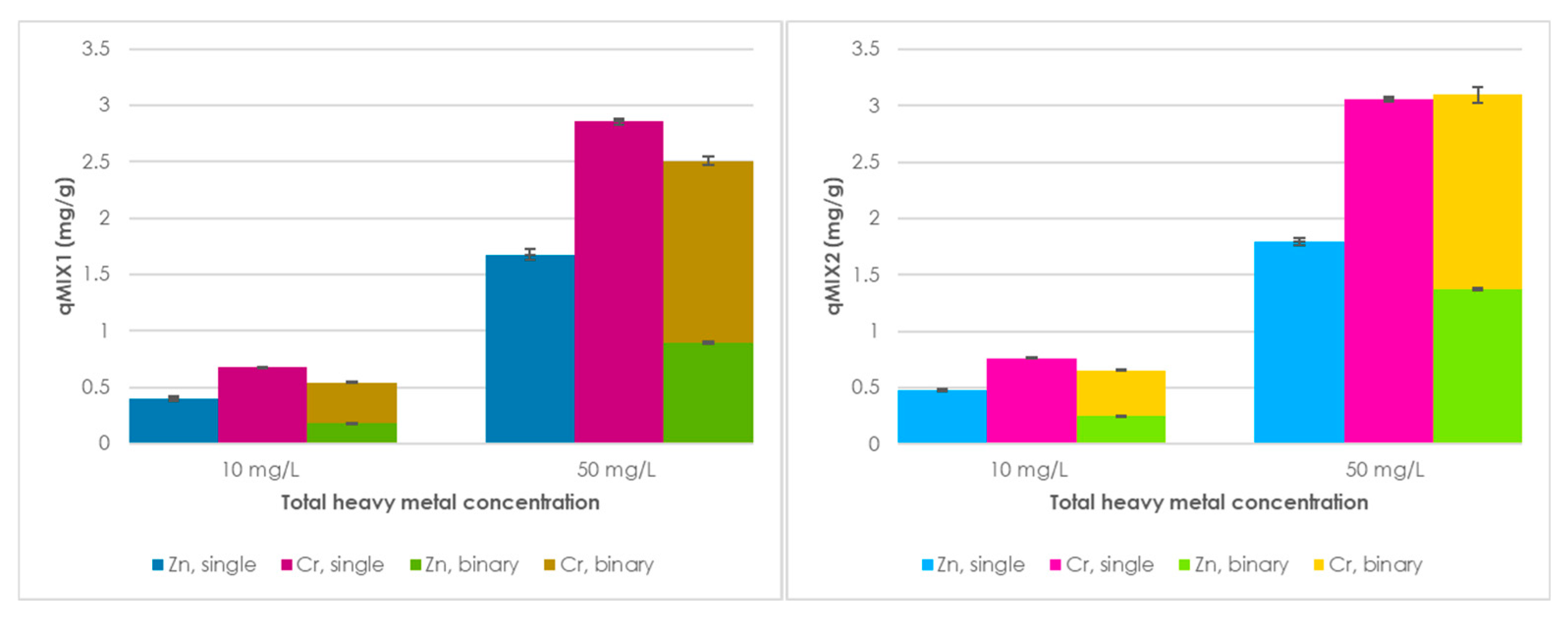

This study explores the potential use of SCPs as novel adsorbent materials for the development of active capping systems that aim to remediate metal-contaminated marine sediments. To this end, zinc and chromium were selected as target contaminants for their properties and high occurrence in real contamination scenarios. More specifically, the former is one of the most transportable and bioavailable heavy metals [

28], whereas the latter is known for its high toxicity and carcinogenicity [

29]. Batch adsorption experiments were carried out in synthetic seawater contaminated with selected concentrations of zinc and chromium, tested both individually and in combination. These conditions were chosen to simulate the interaction between the adsorbent and dissolved contaminants. This aspect is particularly relevant since active capping technologies are designed to act on pollutants present in the porewater of sediments [

30]. The performance of SCPs as adsorbent was compared to that of commercial activated carbon (AC), due to its widespread use and established performance in remediation treatments, providing a suitable benchmark to assess the adsorption efficiency of SCPs. Additionally, different combinations of SCPs and AC were also tested to evaluate potential synergistic effects and to explore the feasibility of using mixed formulations.