Intelligent Prediction Based on NRBO–LightGBM Model of Reservoir Slope Deformation and Interpretability Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Construct an interpretable, multi-point deformation prediction framework (NRBO–LightGBM) that captures temporal coherence among monitoring points.

- Develop an NR-based hyperparameter optimizer for LightGBM to achieve robust convergence under heterogeneous hydro-geological conditions.

- Employ SHAP with partial-dependence diagnostics to quantify global/local attributions that can be applied to determine operational early-warning thresholds.

- Benchmark against statistical model and untuned LightGBM baselines on the Lijiaxia Hydropower Station to demonstrate gains in accuracy, robustness, and interpretability.

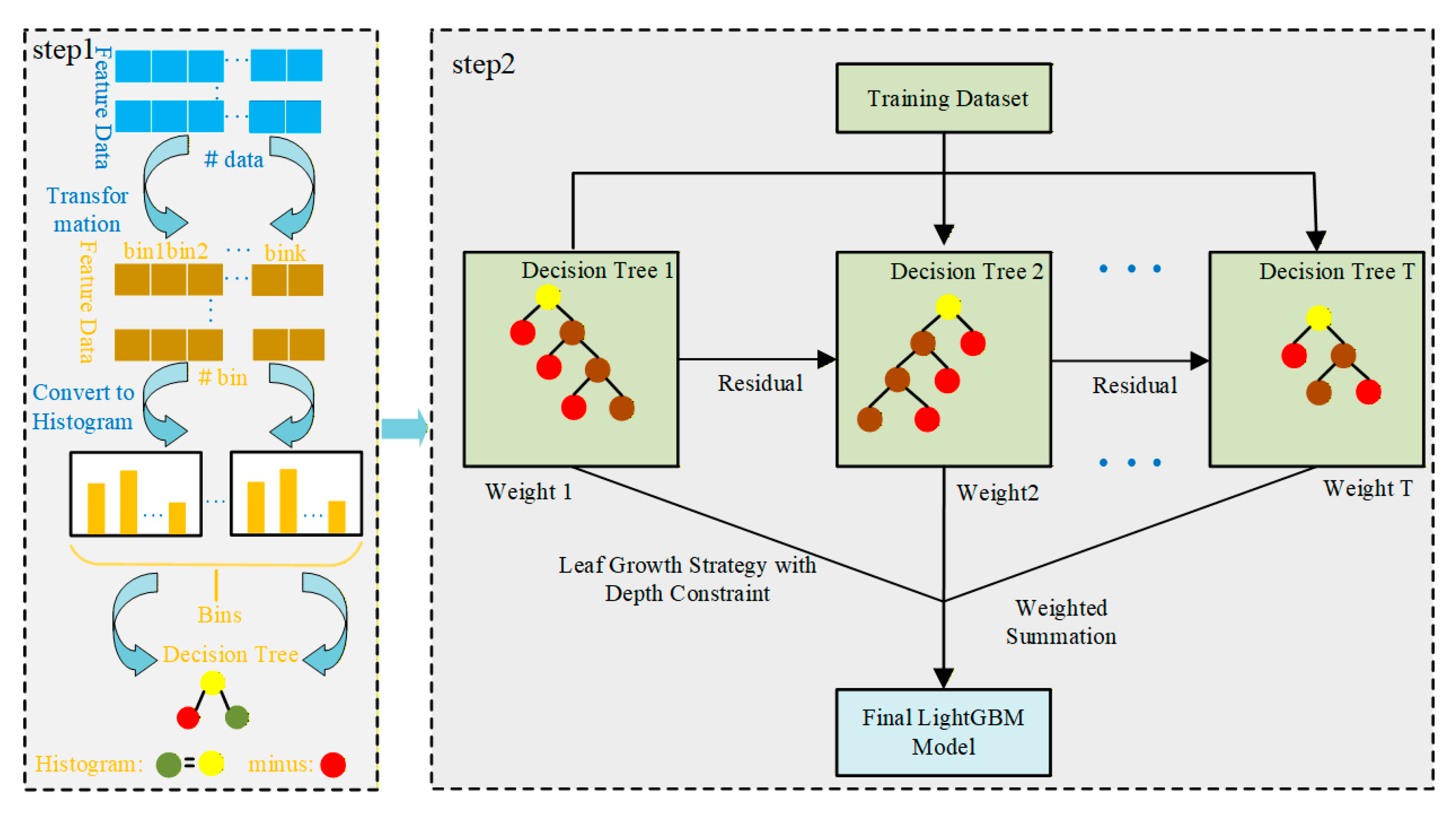

2. Prediction Model Based on Newton–Raphson-Based Optimizer and LightGBM for Slope Deformation

2.1. Conventional Statistical Model

2.2. Principle of the LightGBM Model

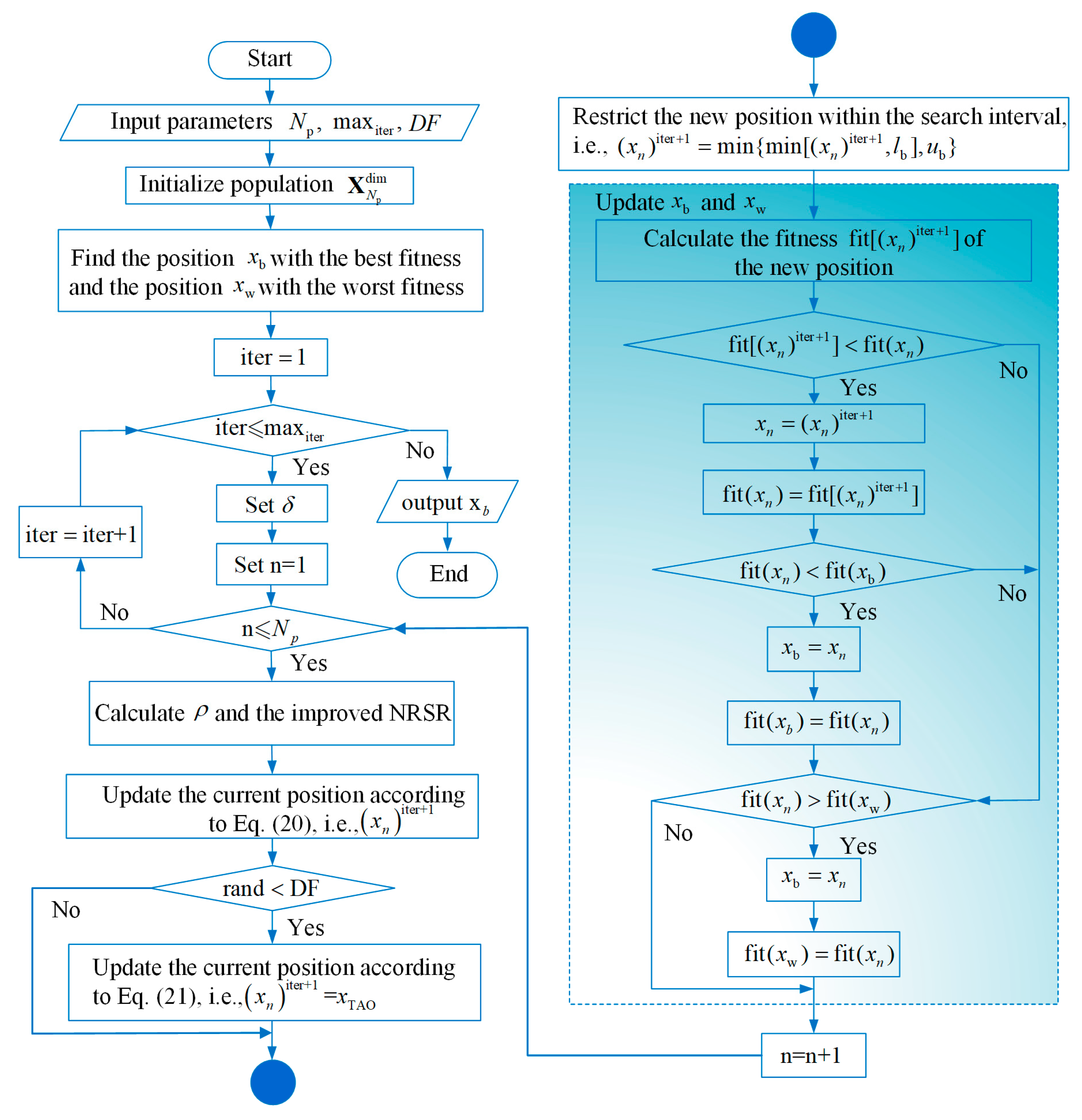

2.3. Principle of the NRBO Algorithm

2.3.1. Construction of the NRSR Search Rule

2.3.2. Trap Avoidance Operation (TAO)

3. Principle of SHAP Interpretability Method

4. Case Study

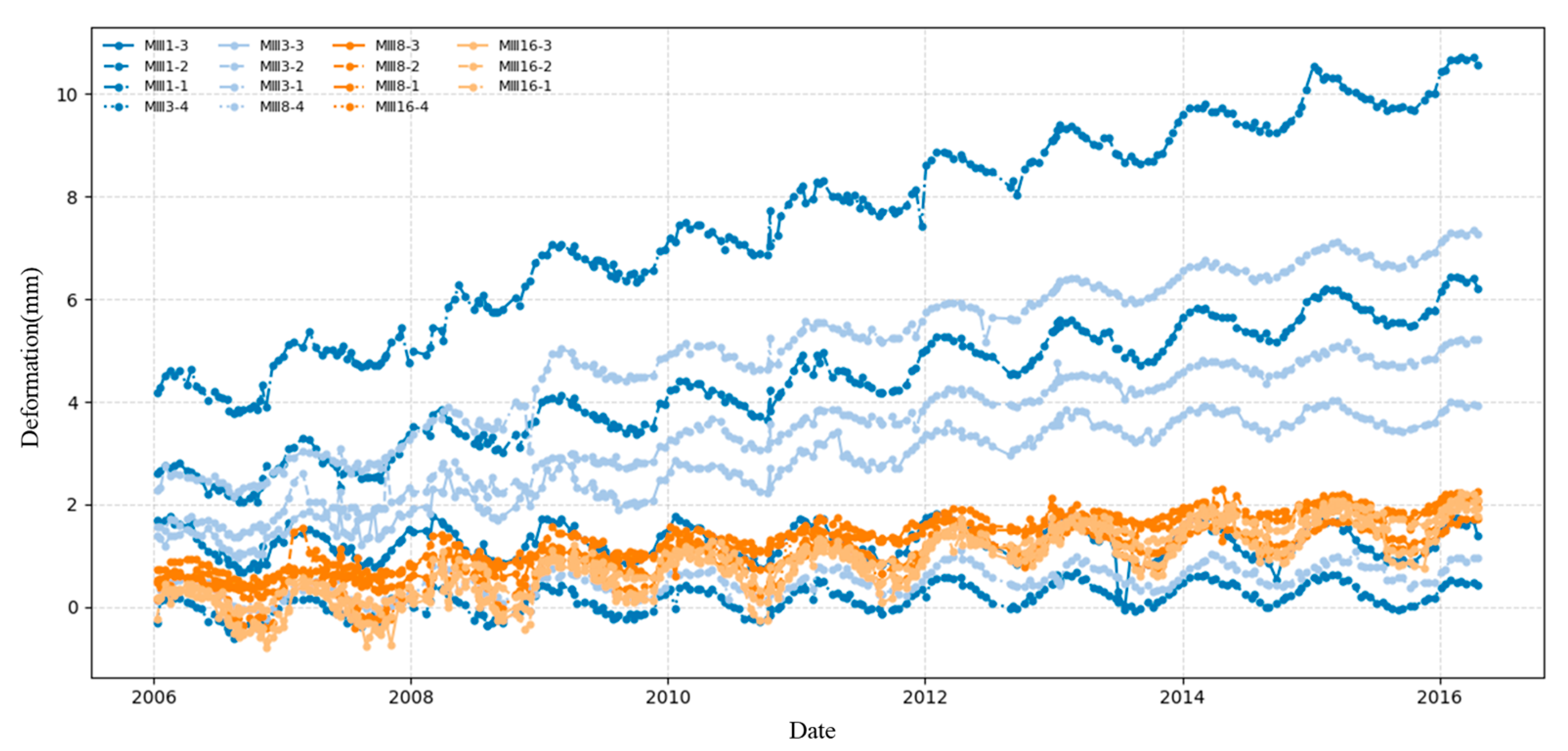

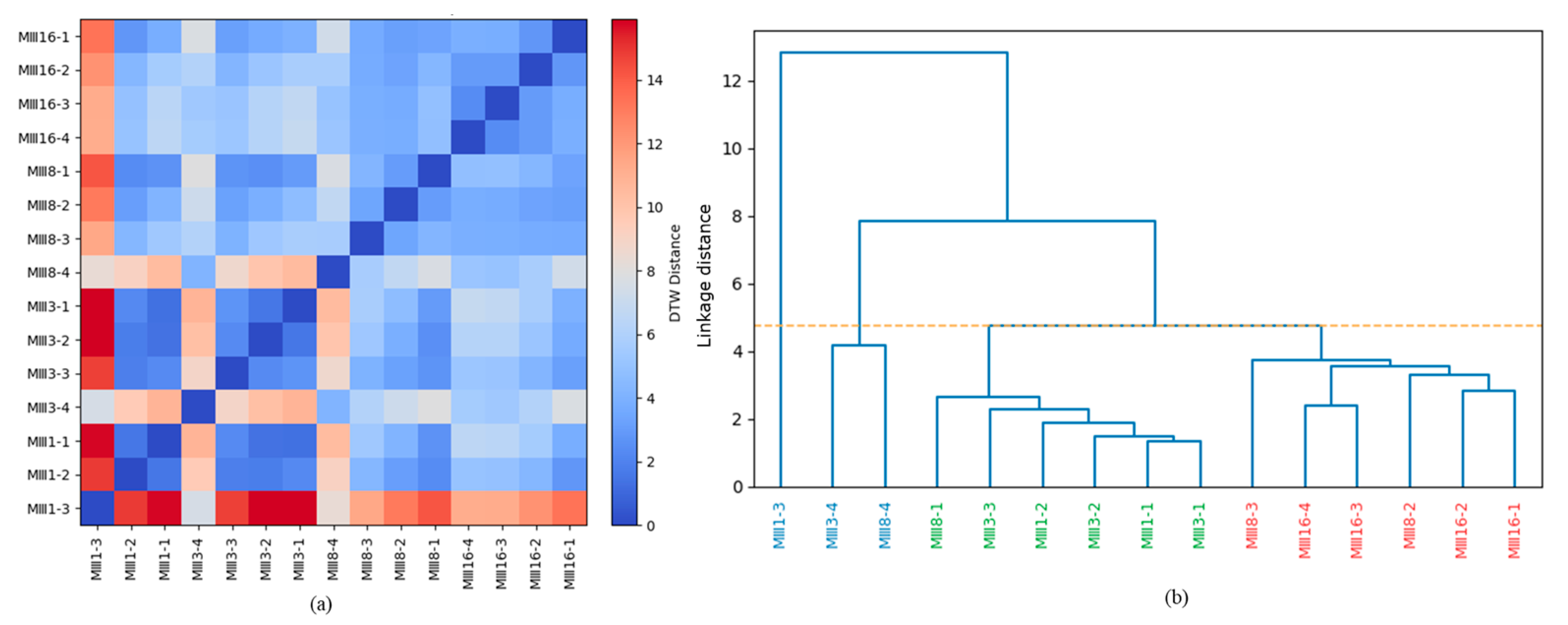

4.1. Datasets

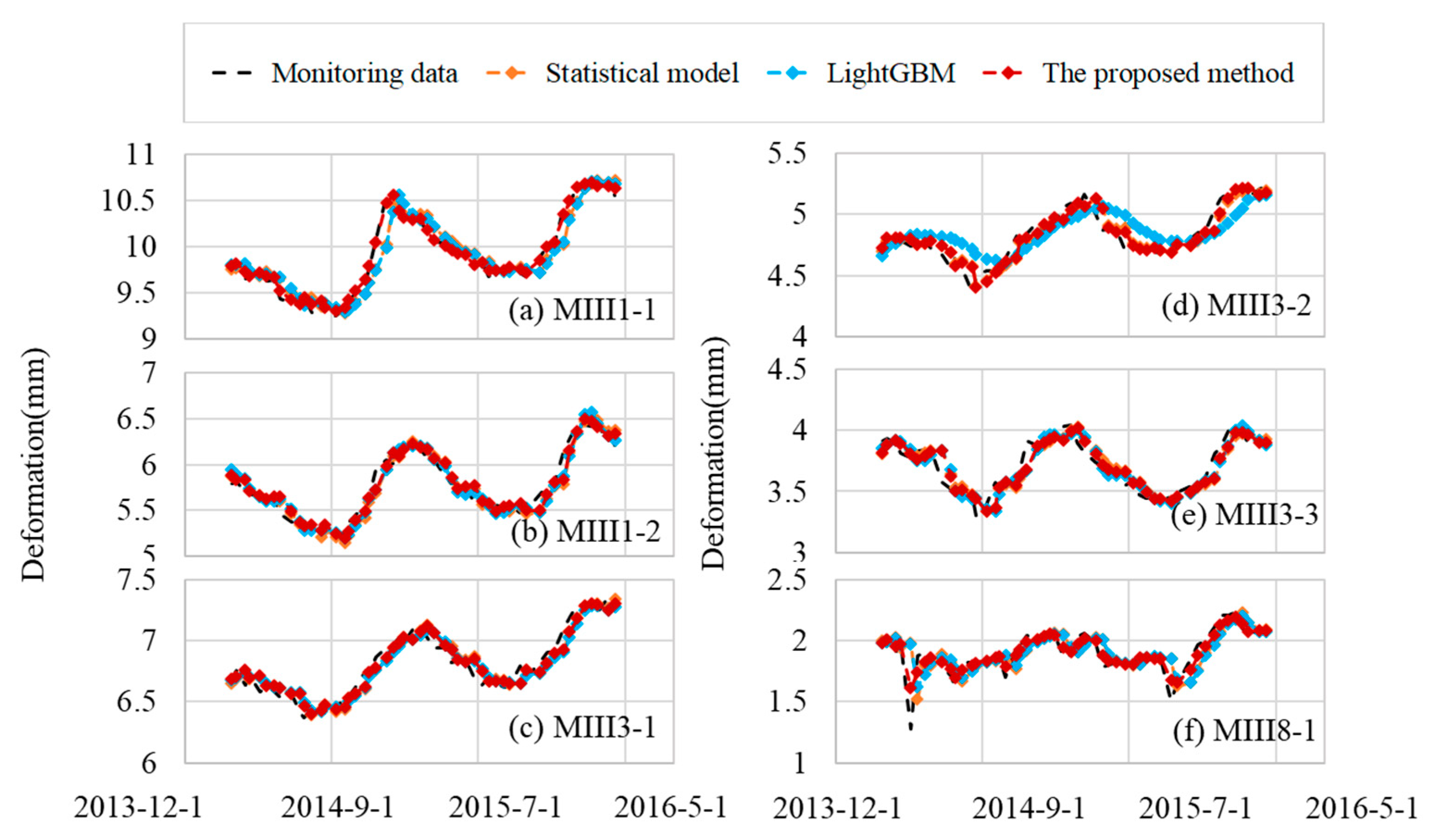

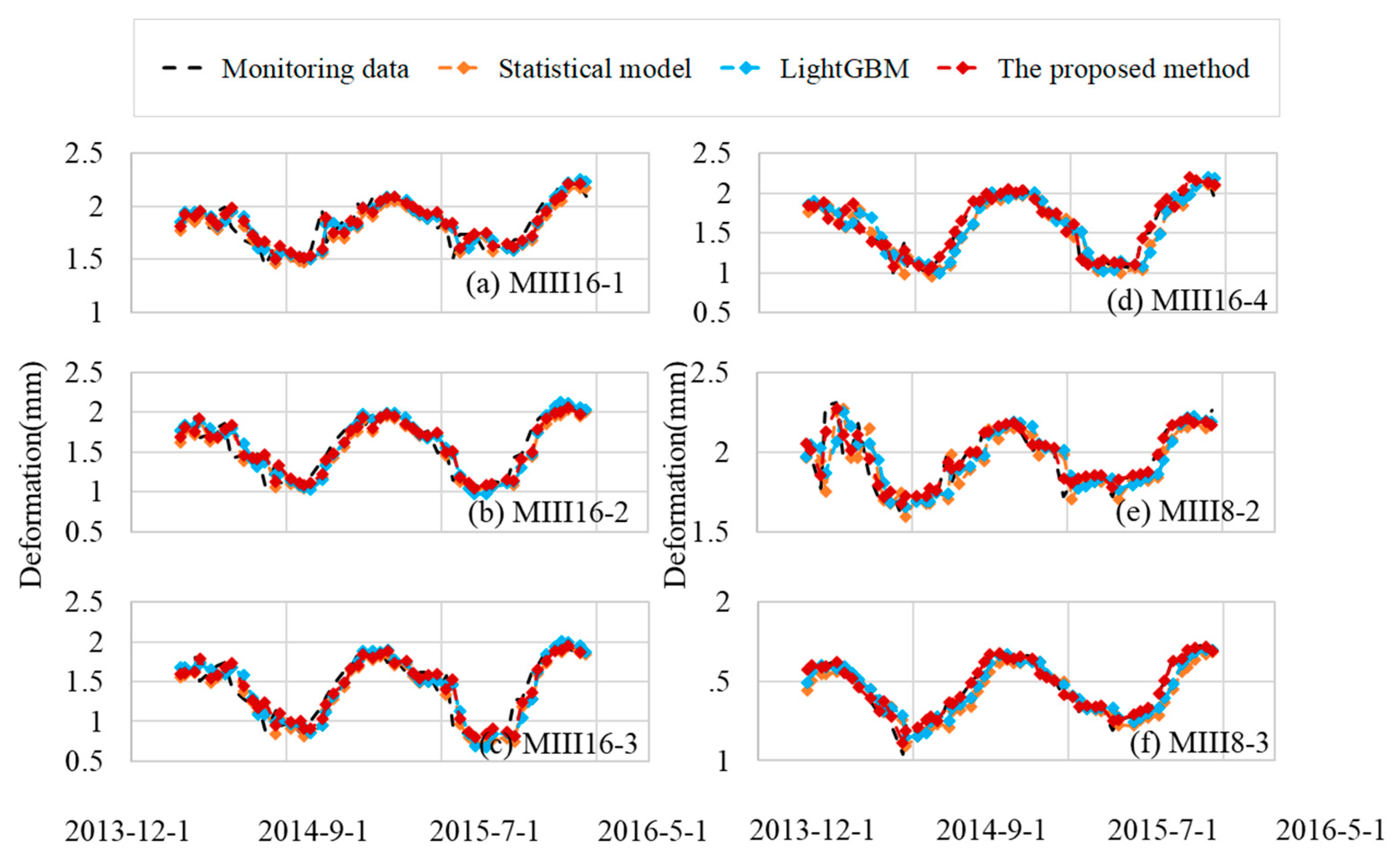

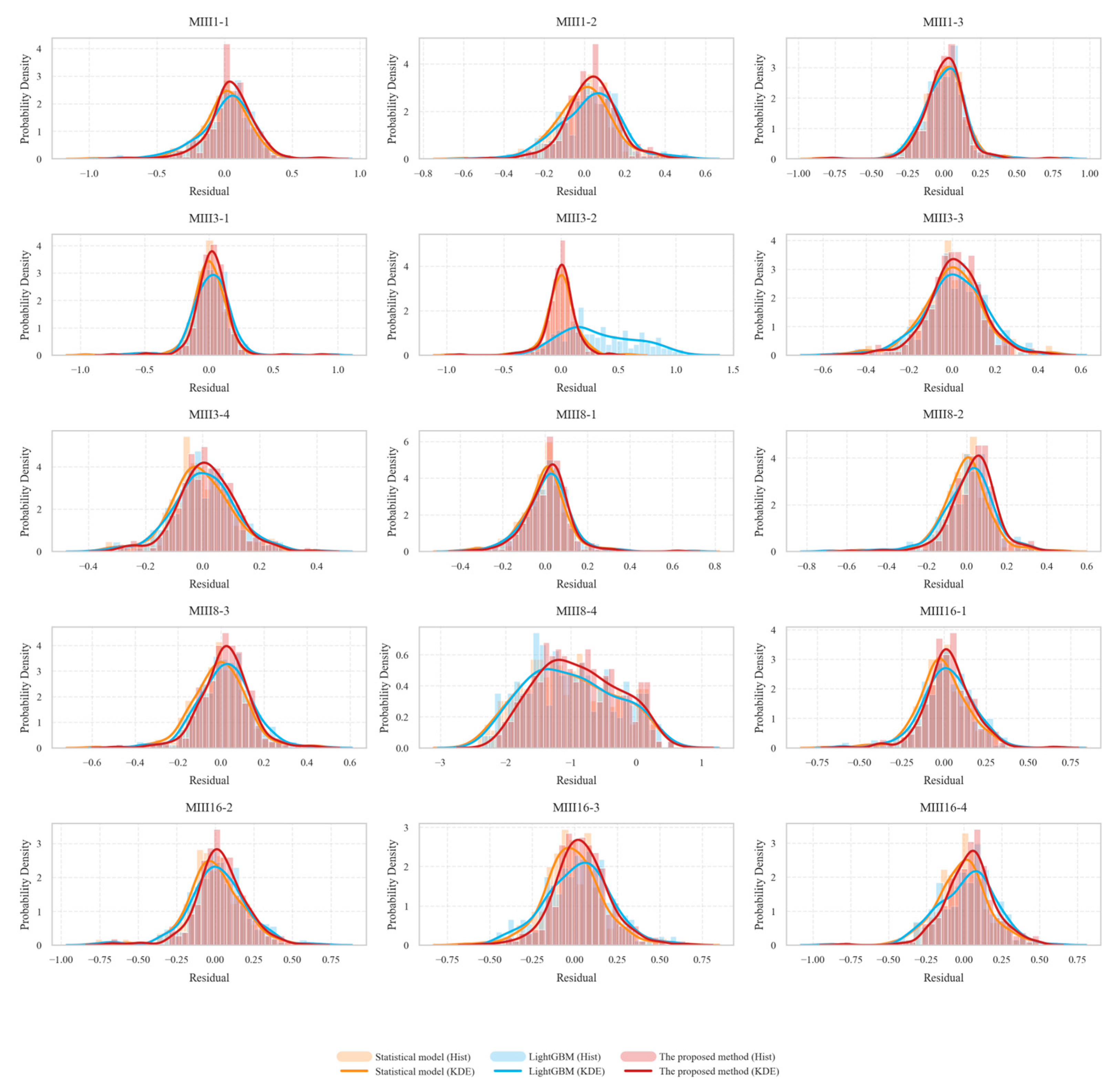

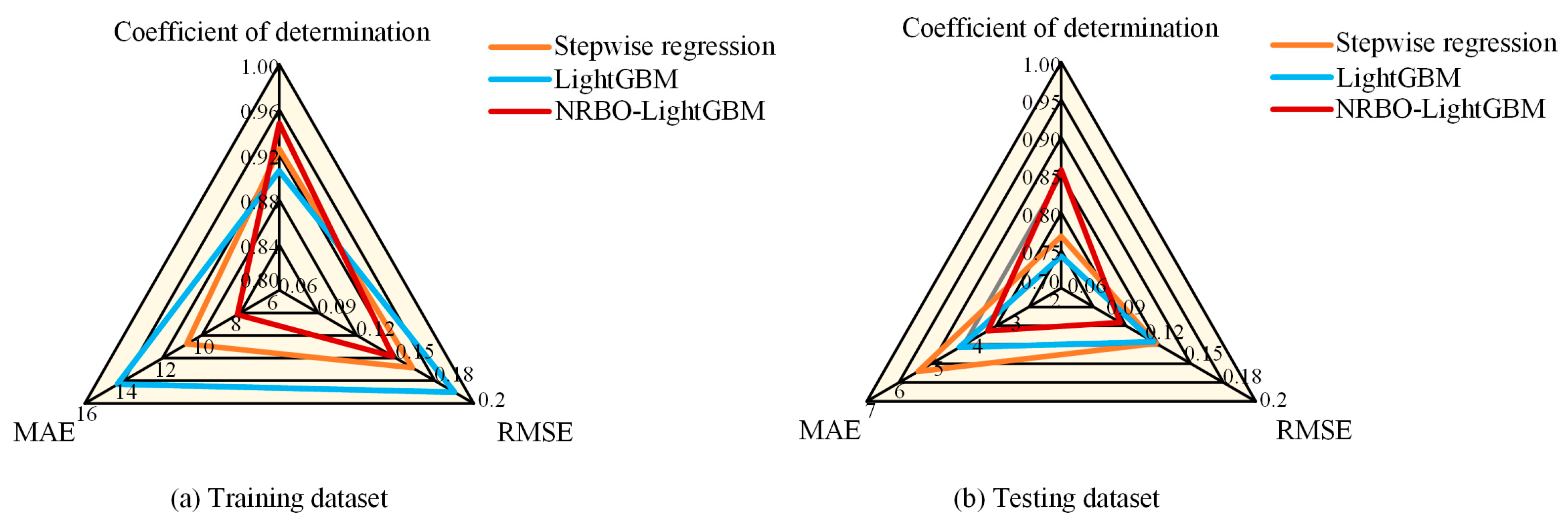

4.2. Results of the Proposed Model and Comprison with Other Models

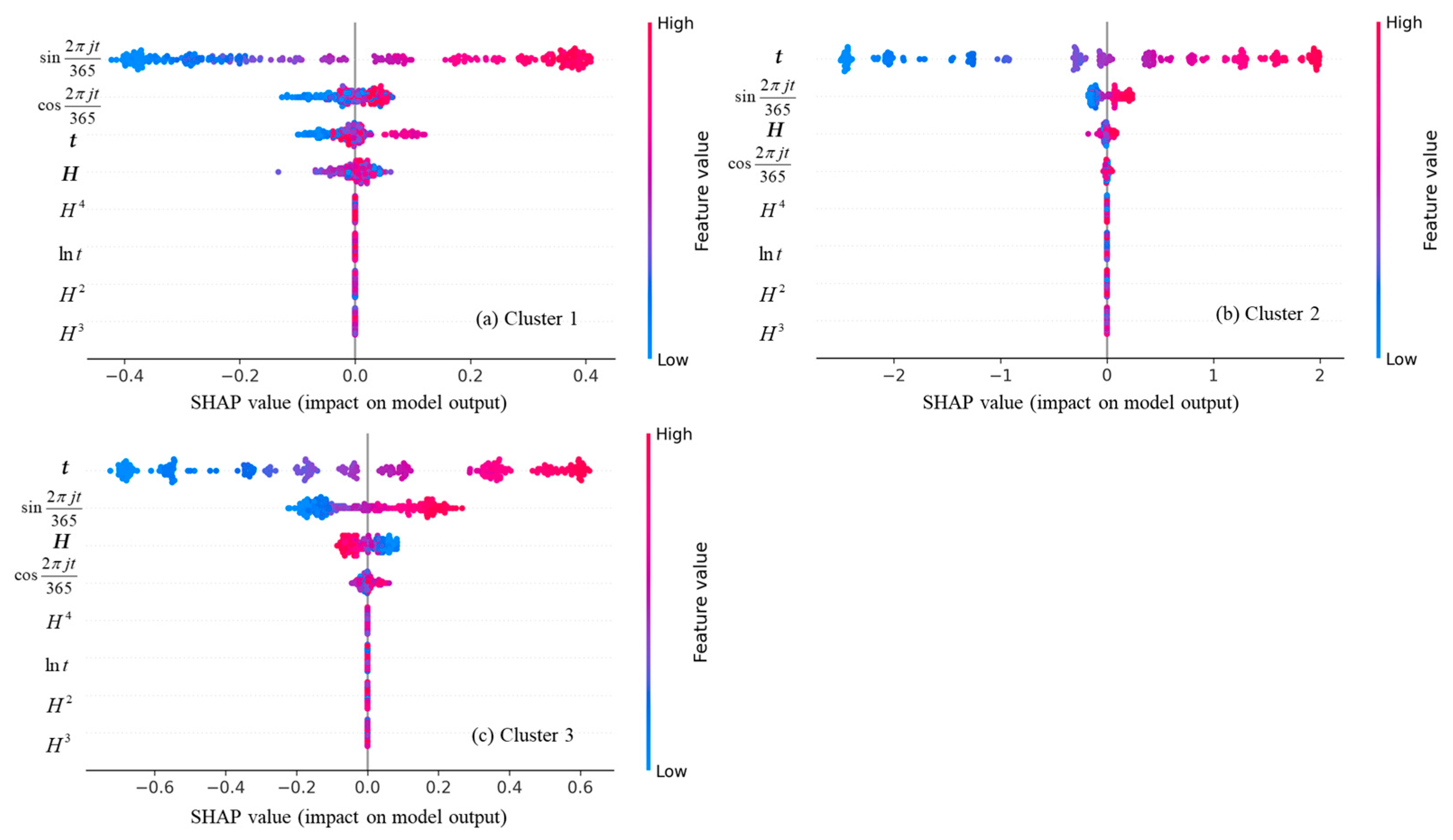

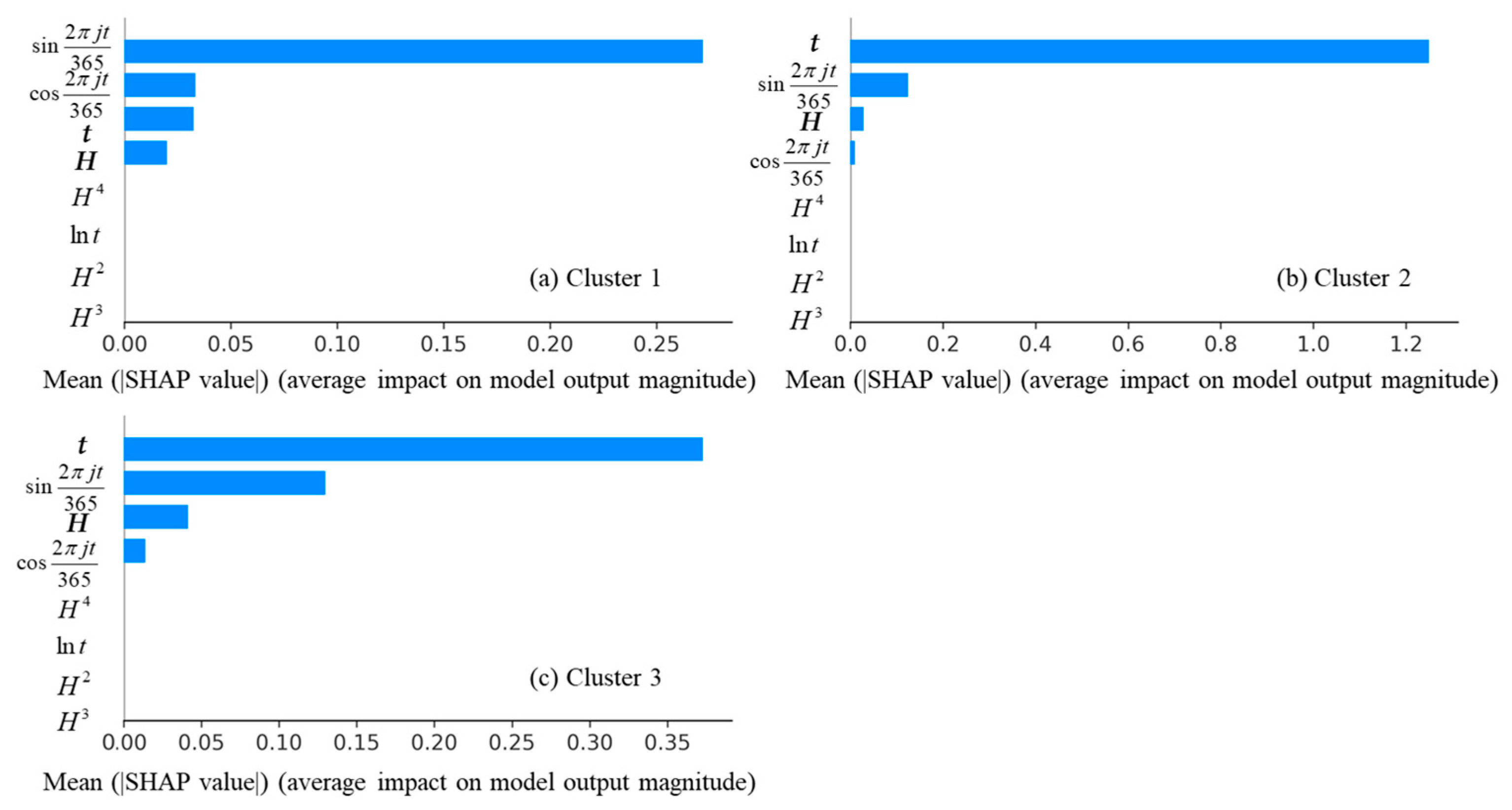

4.3. Shap Analysis

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Fitting and Predicting Results of Other Monitoring Points

Appendix B. Fitting and Predicting Results of Other Monitoring Points

Appendix C. Pseudocode of the NRBO–LightGBM–SHAP Framework

| Algorithm A1. Pseudocode of the proposed framework. |

| Input: Monitoring dataset D = {(Xt, yt)} at N monitoring points Output: Predicted deformation ŷt and SHAP-based feature attributions 1: Data Preprocessing 2: Handle missing values, normalize features, and align time indices. 3: Construct physics-informed and memory features (e.g., rainfall, reservoir level, lagged deformation). 4: Response-Coherent Clustering 5: Cluster deformation series into response-coherent groups using similarity in temporal patterns. 6: For each cluster, initialize LightGBM parameters θ0. 7: NRBO-Based Hyperparameter Optimization 8: For each cluster c do 9: Initialize iteration k = 0. 10: Repeat until convergence 11: Compute gradient: gk = ∂L/∂θk. 12: Compute Hessian: Hk = ∂2L/∂θk2. 13: Update parameters: θk+1 = θk − α·Hk−1·gk, where α is a damping coefficient controlled by line search. 14: End Repeat 15: Obtain optimized parameters θ*. 16: Model Training and Validation 17: Train LightGBM using optimized θ* on the training dataset. 18: Evaluate model on the testing dataset to compute R2, RMSE, and MAE. 19: SHAP-Based Interpretation 20: Compute SHAP values for all input features. 21: Aggregate global and local attributions. 22: Generate feature-importance and partial-dependence plots. 23: Output 24: Predicted deformation series ŷt. 25: SHAP-based feature attributions and derived warning thresholds. |

References

- Huo, T.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Fang, Y.; Gao, B.; Zhang, X. InSAR-Based Surface Deformation Analysis and Trend Prediction in Permafrost Areas Along the Qinghai-Tibet Railway Using Sentinel-1A and Environmental Factors. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 9297–9320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Meng, X.; Liu, S.; Zhu, C. Time Series Prediction of Reservoir Bank Landslide Failure Probability Considering the Spatial Variability of Soil Properties. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 3951–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, Z. Research on the Collapse Process of a Thick-Layer Dangerous Rock on the Reservoir Bank. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, K.; Gou, Q.; Tang, S.; Guo, F. Study on Slope Deformation Partition and Monitoring Point Optimization Considering Spatial Correlation. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 13109–13136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Yang, H.; Liang, D.; Chen, L.; Jaboyedoff, M. Step-Like Displacement Prediction and Failure Mechanism Analysis of Slow-Moving Reservoir Landslide. J. Hydrol. 2024, 628, 130588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Wu, H.; Hu, H.; Azzam, R.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Gong, X. Deformation Prediction of Unstable Slopes Based on Real-Time Monitoring and DeepAR Model. Sensors 2021, 21, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Feng, G.; Wang, J.; Feng, S.; Malekian, R.; Li, Z. A New Machine-Learning Prediction Model for Slope Deformation of an Open-Pit Mine: An Evaluation of Field Data. Energies 2019, 12, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, B.B.; Liu, J.Y. Stepwise Regression Arithmetic and Its Application on Slope Safety Monitoring. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2012, 204–208, 2859–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, X.; Qin, P.; Liu, X.; Cheng, C. PPrediction of Seawater Intrusion Run-Up Distance Based on K-Means Clustering and ANN Model. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuan, P.; Huang, Y. Prediction of Sliding Slope Displacement Based on Intelligent Algorithm. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 102, 3141–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Qiang, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, Z. Research on Slope Deformation Prediction Based on Fractional-Order Calculus Gray Model. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018, 2018, 9526216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Dong, Y.; Shi, W.; Clarke, K.C.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. An Improved Fractal Prediction Model for Forecasting Mine Slope Deformation Using GM (1,1). Struct. Health Monit. 2015, 14, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.W.; Li, Y. A Novel Deformation Forecasting Method Utilizing Comprehensive Observation Data. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1687814018796330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Song, R.; Qu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, H.; Chen, Y. Surface Deformation Prediction Model of High and Steep Open-Pit Slope Based on APSO and TWSVM. Elektronika ir Elektrotechnika 2024, 30, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammady, M.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Amiri, M. Land Subsidence Susceptibility Assessment Using Random Forest Machine Learning Algorithm. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.H.; Li, D.Q.; Tang, X.S.; Rong, G. Machine Learning for Time Series Prediction of Valley Deformation Induced by Impoundment for High Arch Dams. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Chen, L.; Fan, X.; Ma, P.; Zhao, S.; Wu, Z.; Yang, F.; Xu, L.; Shan, M.; Xie, X.; et al. Validating and Enhancing Data-Driven Landslide Susceptibility Prediction by Model Explanation and MT-InSAR Techniques. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2509857. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Li, X. A Novel Prediction Model Construction and Result Interpretation Method for Slope Deformation of Deep Excavated Expansive Soil Canals. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, D. Multifractal Characteristics and Displacement Prediction of Deformation on Tunnel Portal Slope of Shallow-Buried Tunnel Adjacent to Important Structures. Buildings 2024, 14, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lyu, T.L.; Luo, N.; Chang, P. Deformation Prediction of Rock Cut Slope Based on Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2024, 15, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, N.; Yang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Mei, G. Machine Learning Approaches for Slope Deformation Prediction Based on Monitored Time-Series Displacement Data: A Comparative Investigation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Li, B. Deformation Prediction of Cihaxia Landslide Using InSAR and Deep Learning. Water 2022, 14, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özsen, H.; Kaygusuz, B. Experimental Analysis of Various Deep Learning Methods for Predicting Displacements in an Open-Pit Coal Mine. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 20629–20654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Dong, J.; Wei, Z.; Peng, L.; Wu, Q.; Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Xie, F. Landslide Displacement Prediction with Gated Recurrent Unit and Spatial–Temporal Correlation. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 950723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.X.; Xie, K.; Su, Q.; Xu, L.R.; Hao, Z.R.; Xiao, X.P. Three-Level Evaluation Method of Cumulative Slope Deformation Hybrid Machine-Learning Models and Interpretability Analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Yao, S. Slope Deformation Prediction Combining Particle Swarm Optimization-Based Fractional-Order Grey Model and K-Means Clustering. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.F.; Yang, J.; Qin, Y.Y. Prediction of Optimal Design Parameters for Reinforced Soil Embankments with Wrapped Faces Using a GA-BP Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6910. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, T.K.; Zhou, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.G.; Zhang, J. A Novel Inversion Method of Slope Rock Mechanical Parameters Using Differential Evolution Gray Wolf Algorithm to Optimize Support Vector Regression. Front. Earth Sci. 2025, 13, 1575194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.C.; Nait Amar, M.; Motahari, M.R.; Hasanipanah, M.; Armaghani, D.J. Two Novel Combined Systems for Predicting the Peak Shear Strength Using RBFNN and Meta-Heuristic Computing Paradigms. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, W.B. Predictive Models for Earthquake-Induced Landslides: Machine Learning Based on Real Case Histories. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method Family | Representative Models | Typical Strengths | Typical Limitations in Reservoir-Slope Forecasting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanics-informed decompositions | Hydraulic–seasonal–aging models; polynomial/d-lag, harmonic | Physically interpretable; parsimonious; easy to calibrate | Struggle with step-like kinematics, nonstationary, missing data, nonlinear interactions |

| Classical ML | SVM, RF, GBDT/LightGBM | Handles heterogeneity; good tabular performance; modest data requirement | Sensitive to hyperparameters; limited intrinsic interpretability; often site-wise calibration |

| Deep/sequence models | RNN/LSTM/GRU, CNN–RNN hybrids | Capture temporal dependence; flexible nonlinear mapping | Harder to interpret; prone to overfit; less robust to regime shifts/data gaps |

| Hybrid physics–ML | Physics-guided features + ML | Leverage domain constraints; improved extrapolation | Added feature engineering; require tuning and validation |

| Optimization metaheuristics | PSO, GA, GWO/WOA/ACO | Derivative-free; broad applicability; easy to implement | Sample-inefficient; slow convergence; high variance in optima |

| Proposed method | NRBO–LightGBM | Second-order, fast convergence; strong tabular accuracy; transparent attributions; supports thresholding | Dependent on data quality |

| Monitoring Point | R2 (/) | RMSE (mm) | MAE (/) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1 | MIII1-3 | 0.8511 | 0.1367 | 10.8804 |

| Cluster 2 | MIII1-2 | 0.9524 | 0.1377 | 3.6094 |

| Cluster 2 | MIII1-1 | 0.9832 | 0.1992 | 2.8156 |

| Cluster 1 | MIII3-4 | 0.8571 | 0.0998 | 16.5742 |

| Cluster 2 | MIII3-3 | 0.971 | 0.1361 | 5.8268 |

| Cluster 2 | MIII3-2 | 0.9823 | 0.1338 | 4.0285 |

| Cluster 2 | MIII3-1 | 0.9734 | 0.1433 | 2.8511 |

| Cluster 1 | MIII8-4 | 0.8731 | 0.1035 | 14.6751 |

| Cluster 3 | MIII8-3 | 0.896 | 0.1188 | 15.5457 |

| Cluster 3 | MIII8-2 | 0.9421 | 0.114 | 9.6902 |

| Cluster 2 | MIII8-1 | 0.9903 | 0.0855 | 8.684 |

| Cluster 3 | MIII16-4 | 0.9292 | 0.1682 | 12.3182 |

| Cluster 3 | MIII16-3 | 0.9446 | 0.1672 | 16.4529 |

| Cluster 3 | MIII16-2 | 0.9436 | 0.1758 | 22.423 |

| Cluster 3 | MIII16-1 | 0.943 | 0.1465 | 15.0848 |

| Model | Coefficient of Determination (R2) | RMSE | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stepwise | 0.769 | 0.123 | 5.681 |

| LightGBM | 0.742 | 0.121 | 4.619 |

| NRBO–LightGBM | 0.857 | 0.095 | 3.889 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Xia, Y.; Xiong, F.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Hu, Y.; Shao, C. Intelligent Prediction Based on NRBO–LightGBM Model of Reservoir Slope Deformation and Interpretability Analysis. Water 2025, 17, 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223248

Chen J, Sun J, Xia Y, Xiong F, Li X, Liu C, Hu Y, Shao C. Intelligent Prediction Based on NRBO–LightGBM Model of Reservoir Slope Deformation and Interpretability Analysis. Water. 2025; 17(22):3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223248

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiang, Jiwan Sun, Yang Xia, Fangjin Xiong, Xuefei Li, Chenrui Liu, Yating Hu, and Chenfei Shao. 2025. "Intelligent Prediction Based on NRBO–LightGBM Model of Reservoir Slope Deformation and Interpretability Analysis" Water 17, no. 22: 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223248

APA StyleChen, J., Sun, J., Xia, Y., Xiong, F., Li, X., Liu, C., Hu, Y., & Shao, C. (2025). Intelligent Prediction Based on NRBO–LightGBM Model of Reservoir Slope Deformation and Interpretability Analysis. Water, 17(22), 3248. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223248