Effects of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events on the Functioning of Mountain Environments in the Ochotnica Catchment (Outer Carpathians, Poland) and Recommendations for Adaptation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

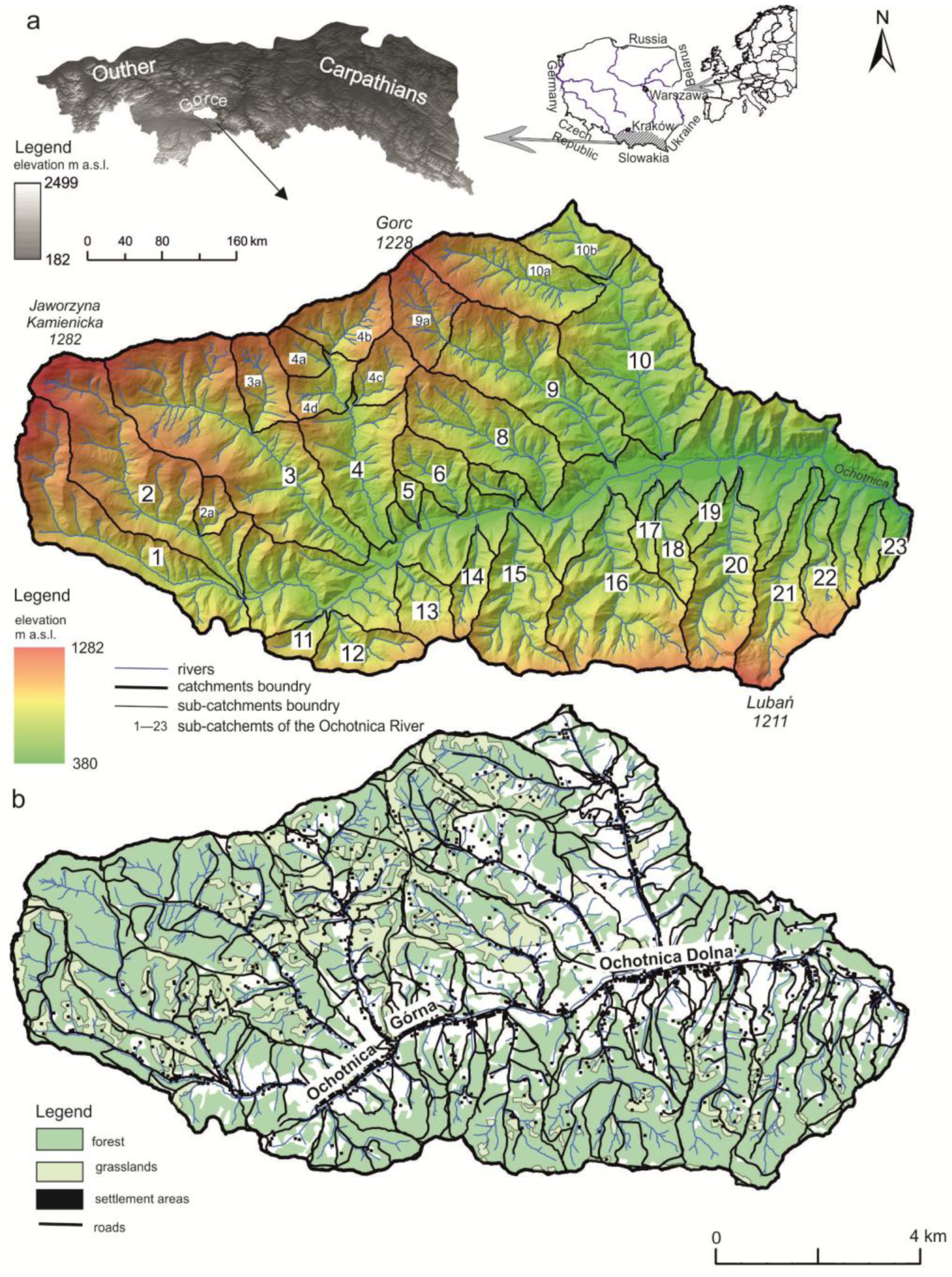

2. Materials and Methods

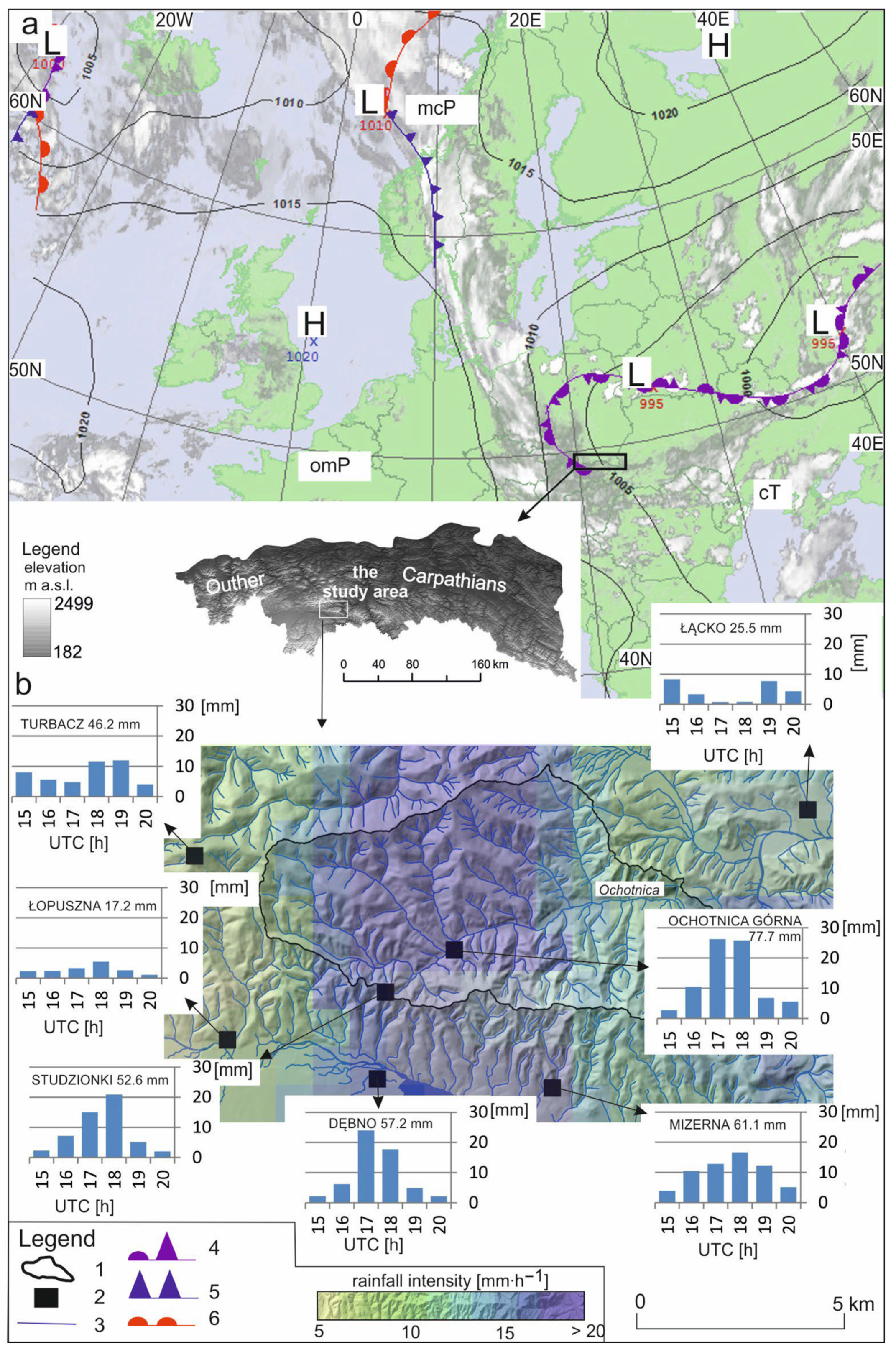

2.1. Meteorological Settings

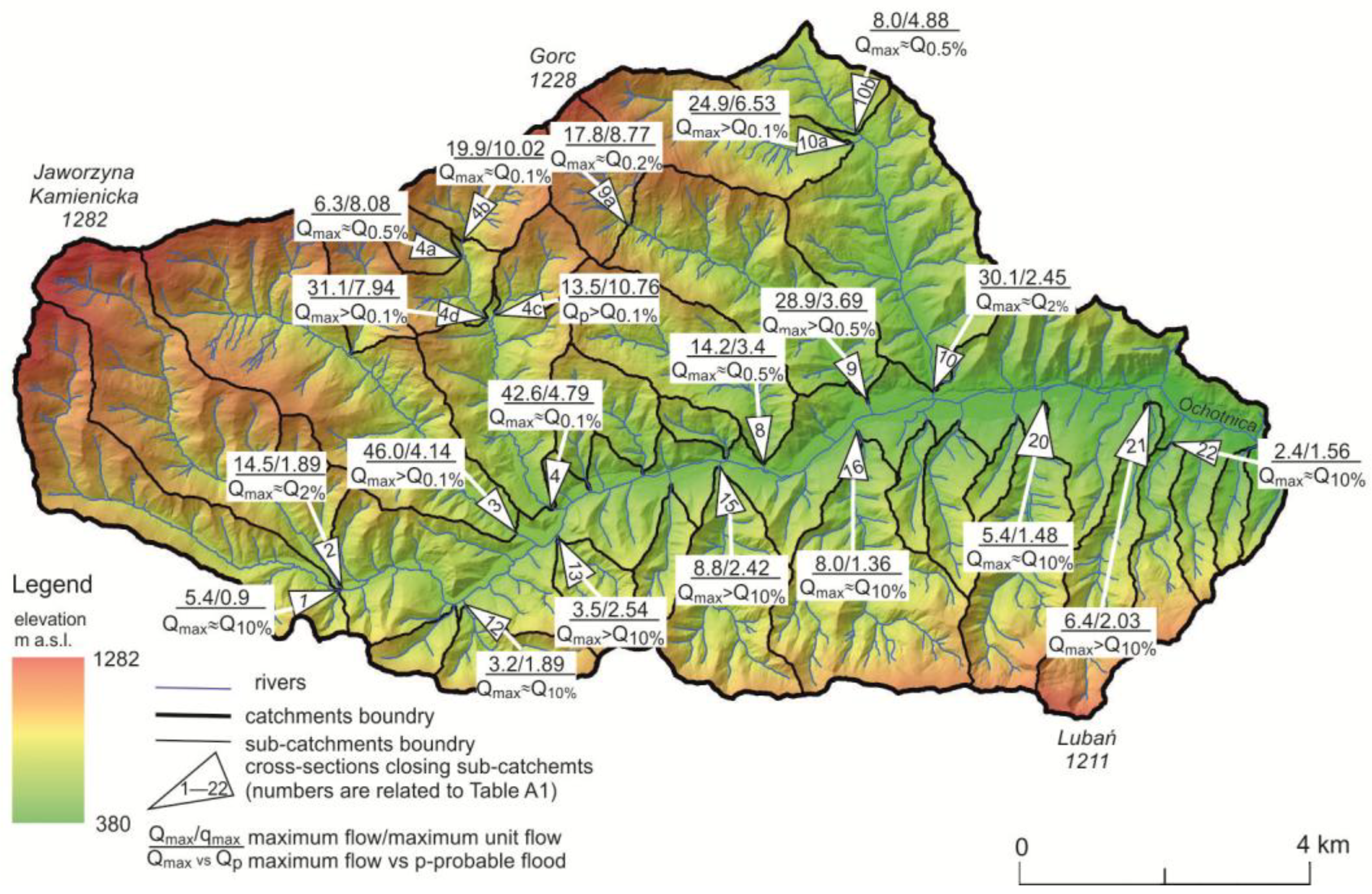

2.2. Hydrological Response

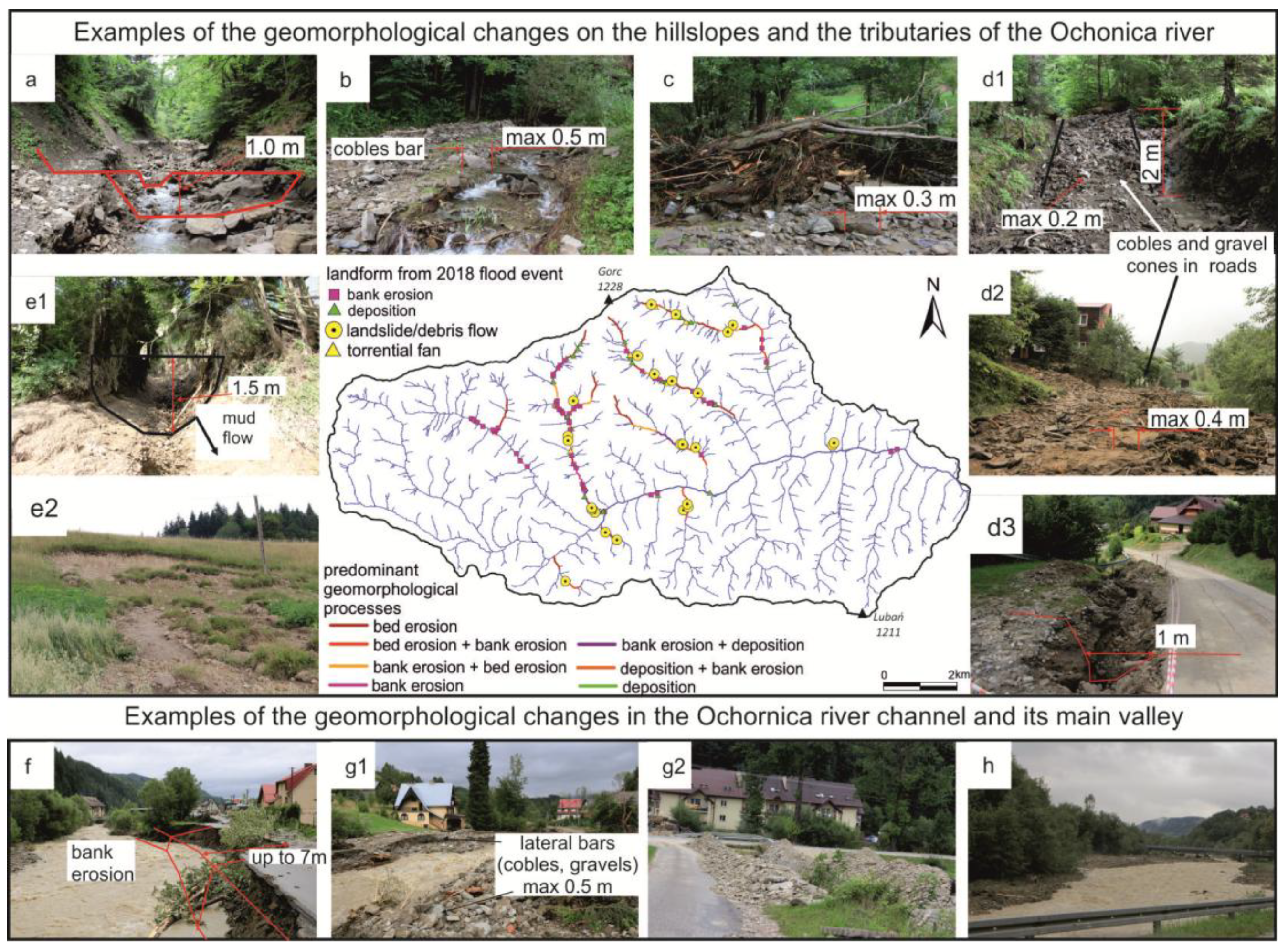

2.3. Environmental and Economic Consequences

2.4. Record of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events in Mountain Environment

3. The Study Area

4. Results

4.1. Meteorological Settings of a Rainstorm

4.2. Hydrological Response of a Catchment

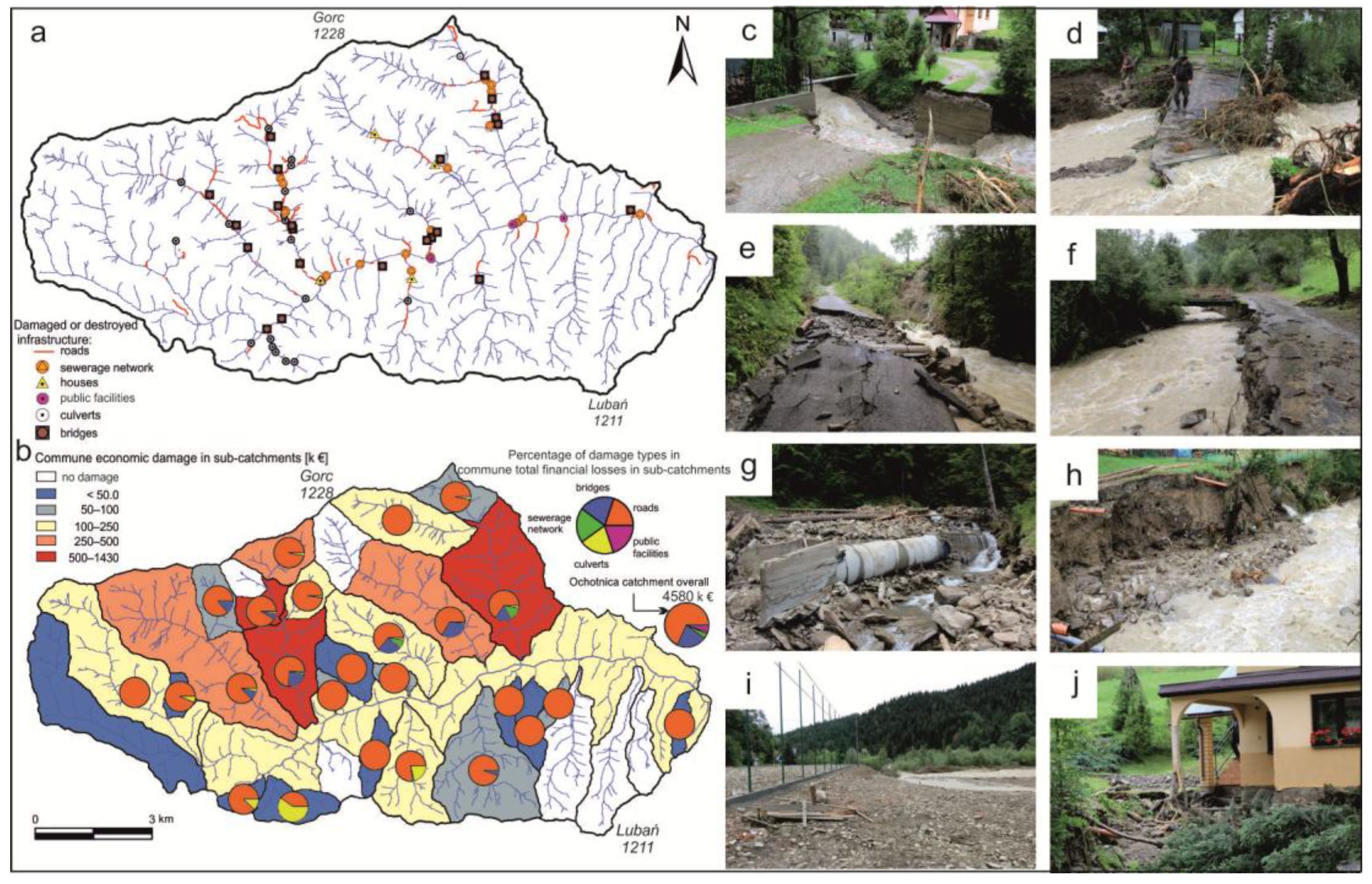

4.3. Environmental and Economic Consequences

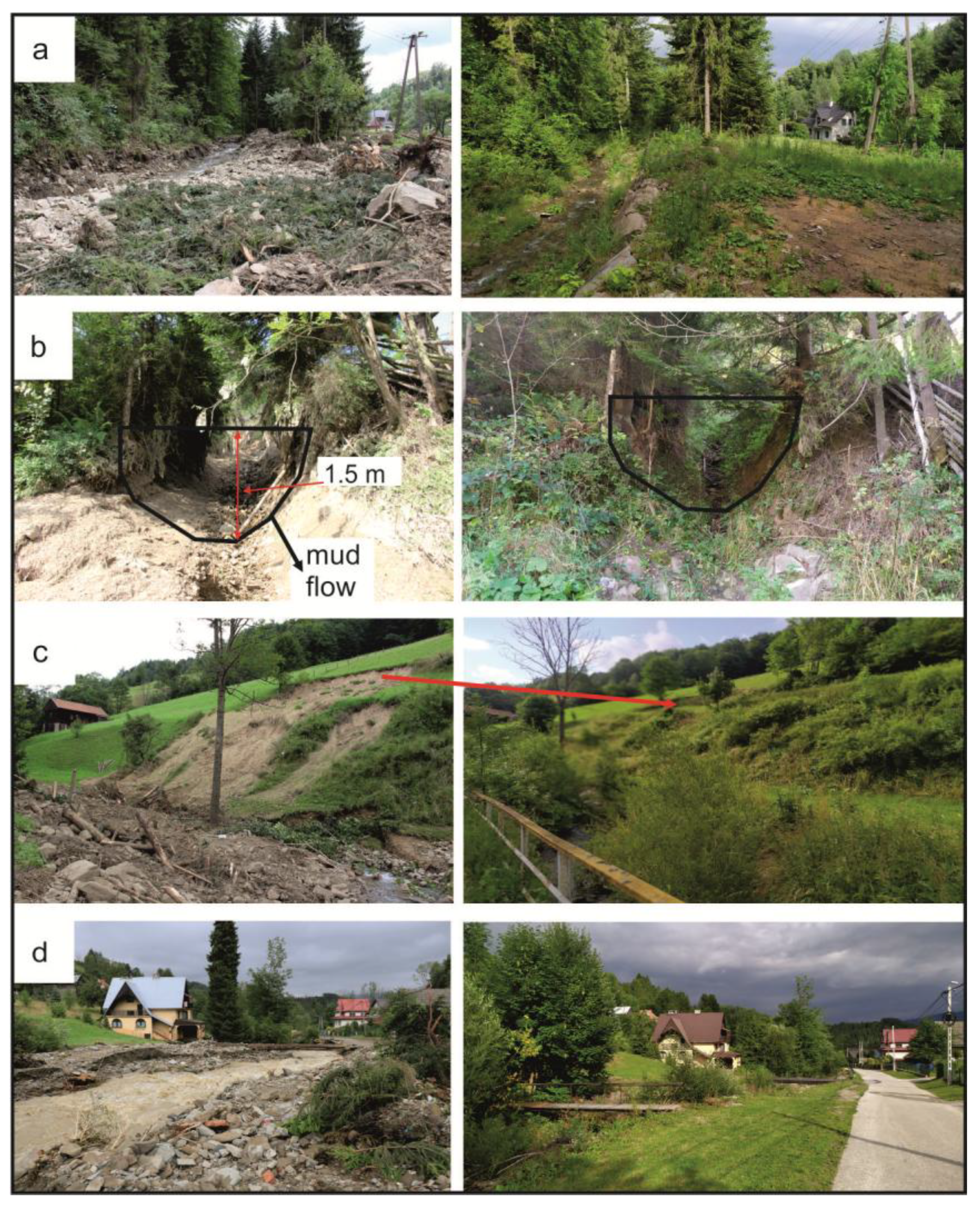

4.4. Record of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Event in Mountain Environment

5. Discussion—Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events in Mountain Areas

5.1. Triggering Factors and the Flood Magnitude

5.2. Environmental and Economic Consequences

5.3. Reducing the Negative Effects of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events in Mountain Areas—Recommendations for Adaptation Strategies

5.3.1. Flood Hazard

5.3.2. Flood Exposure and Vulnerability

Design and Function of Road Networks

Design and Function of Bridges and Culverts

Design and Function of Residential Infrastructure

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Cross-Section Number | Sub-Catchments Name | Area [km2] | Qmax [m3·s−1] | qmax [m3·s−1·km−2] | P-Probable Flood [%] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 10 | 50 | |||||

| [m3·s−1] | |||||||||||

| 1 | Furcówka | 5.95 | 5.4 | 0.91 | 24.69 | 21.96 | 18.6 | 16.03 | 13.51 | 7.73 | 2.32 |

| 2 | Forendówki | 7.67 | 14.5 | 1.89 | 30.41 | 27.05 | 22.91 | 19.75 | 16.65 | 9.52 | 2.86 |

| 3 | Jaszcze | 11.21 | 46.0 | 4.14 | 43.76 | 38.93 | 32.96 | 28.42 | 23.96 | 13.7 | 4.12 |

| 4 | Jamne | 8.89 | 42.6 | 4.79 | 45.55 | 40.52 | 34.31 | 29.58 | 24.93 | 14.26 | 4.29 |

| 4a | Skałka | 0.78 | 6.3 | 8.08 | 8.22 | 7.31 | 6.19 | 5.34 | 4.5 | 2.57 | 0.77 |

| 4b | Jamne (upper part) | 1.99 | 19.9 | 10.02 | 20.92 | 18.61 | 15.76 | 13.58 | 11.45 | 6.55 | 1.97 |

| 4c | Pierdołowski Potok | 1.25 | 13.5 | 10.76 | 9.73 | 8.65 | 7.33 | 6.32 | 5.32 | 3.04 | 0.92 |

| 4d | Jamne (middle part) | 3.91 | 31.1 | 7.94 | 28.6 | 25.45 | 21.55 | 18.57 | 15.66 | 8.95 | 2.69 |

| 8 | Skrodne | 4.17 | 14.2 | 3.40 | 19.81 | 17.63 | 14.93 | 12.87 | 10.85 | 6.2 | 1.87 |

| 9 | Gorcowe | 7.83 | 28.9 | 3.69 | 36.87 | 32.8 | 27.77 | 23.94 | 20.18 | 11.54 | 3.47 |

| 9a | Gorcowe (upper part) | 2.03 | 17.8 | 8.77 | 21.42 | 19.05 | 16.13 | 13.91 | 11.72 | 6.7 | 2.02 |

| 10 | Młynne | 12.29 | 30.1 | 2.45 | 53.98 | 48.02 | 40.66 | 35.05 | 29.55 | 16.89 | 5.08 |

| 10a | Młynne (upper part) | 3.82 | 24.9 | 6.51 | 24.72 | 21.99 | 18.62 | 16.05 | 13.53 | 7.74 | 2.33 |

| 10b | Wierch Młynne | 1.64 | 8.0 | 4.88 | 10.18 | 9.06 | 7.67 | 6.61 | 5.57 | 3.19 | 0.96 |

| 12 | Mostkowe | 1.68 | 3.2 | 1.89 | 11.9 | 10.59 | 8.97 | 7.73 | 6.52 | 3.73 | 1.12 |

| 13 | Zawadowski | 1.39 | 3.5 | 2.54 | 10.01 | 8.91 | 7.54 | 6.5 | 5.48 | 3.13 | 0.94 |

| 15 | Jurkowski Potok | 3.62 | 8.8 | 2.42 | 20.06 | 17.85 | 15.11 | 13.03 | 10.98 | 6.28 | 1.89 |

| 16 | Kudowe | 5.84 | 8.0 | 1.36 | 29.16 | 25.94 | 21.97 | 18.94 | 15.96 | 9.13 | 2.75 |

| 20 | Lubanski | 3.67 | 5.4 | 1.48 | 18.62 | 16.56 | 14.02 | 12.09 | 10.19 | 5.83 | 1.75 |

| 21 | Rolnicki | 3.14 | 6.4 | 2.03 | 14.91 | 13.26 | 11.23 | 9.68 | 8.16 | 4.67 | 1.4 |

| 22 | Janczurowski | 1.56 | 2.4 | 1.56 | 9.47 | 8.43 | 7.13 | 6.15 | 5.19 | 2.96 | 0.89 |

| 23 | Ligasy | 0.64 | - | - | 5.18 | 4.61 | 3.9 | 3.37 | 2.84 | 1.62 | 0.49 |

| Lp | River | Cross-Section | A [km2] | Qmax [m3·s−1] | qmax [m3·s−1·km2] | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poland | ||||||

| 1 | cwn | Pilzno | 7.5 | 35 | 4.6 | 3.7 |

| 2 | Dołżyca | Dołżyca | 9.7 | 42.6 | 4.4 | 3.8 |

| 3 | cwn | Szymbark | 1.8 | 16.29 | 9.1 | 3.8 |

| 4 | Kalniczka | Kalnica | 4.3 | 28.8 | 7.1 | 3.8 |

| 5 | cwn | Błędówka | 5 | 32 | 6.6 | 3.8 |

| 6 | cwn | Mała P1 | 8.7 | 56.5 | 6.5 | 4.0 |

| 7 | Wątok | Szynwałd P1 | 2.6 | 32.3 | 12.4 | 4.1 |

| 8 | Kisielina | Łysa Góra P1 | 2.7 | 34.6 | 12.8 | 4.1 |

| 9 | Kisielina | Sufczyn P3 | 10.1 | 77.2 | 7.6 | 4.1 |

| 10 | Bielanka | Szymbark | 6.5 | 75 | 11.5 | 4.3 |

| 11 * | Skrodne | 8 | 4.17 | 14.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Wierch Młynne | 10b | 1.64 | 8 | 4.88 | 3.5 | |

| Skałka | 4a | 0.78 | 6.3 | 8.1 | 3.6 | |

| Gorcowe | 9 | 7.83 | 28.9 | 3.7 | 3.6 | |

| Jaszcze | 4 | 11.4 | 46.5 | 4.1 | 3.8 | |

| Młynne (upper part) | 10a | 3.82 | 24.9 | 6.51 | 3.8 | |

| Jamne | 3 | 8.8 | 42.6 | 4.8 | 3.8 | |

| Gorcowe (upper part) | 9a | 2.03 | 17.8 | 8.8 | 3.8 | |

| Pierdołowski Potok | 4c | 1.25 | 13.5 | 10.8 | 3.8 | |

| Jamne (upper part) | 4b | 1.99 | 19.9 | 10.0 | 3.9 | |

| Jamne (middle part) | 4d | 3.91 | 31.1 | 7.9 | 3.9 | |

| Slovakia | ||||||

| 12 | Malina | Kuchyňa | 7.94 | 3.564 | 0.4 | 2.3 |

| 13 | Sološnický potok | Sološnica | 10.38 | 5.728 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| 14 | Turniansky creek | below Rígeľský creek | 9.08 | 17 | 1.9 | 3.2 |

| 15 | Hukov creek | ústie (confluence) | 8.08 | 20 | 2.5 | 3.4 |

| 16 | Rígeľský creek | ústie (confluence) | 3.88 | 15 | 3.9 | 3.5 |

| 17 | Ždiarsky creek | below Zálešovský | 5.4 | 46.8 | 8.7 | 4.0 |

| 18 | Dubovický potok (creek) | above Dubovica | 10.9 | 120 | 11.0 | 4.4 |

| 19 | Malá Svinka | above Renčišovský potok (creek) | 6.45 | 90 | 14.0 | 4.4 |

| 20 | Renčišovský potok (creek) | ústie (confluence) | 7.06 | 95 | 13.5 | 4.4 |

| 21 | Štrbský Creek | Štrba -first bridge | 2.5 | 65 | 26.0 | 4.5 |

| Romania | ||||||

| 22 | Urlatoarea | Orb Confluence | 4.6 | 30 | 6.5 | 3.8 |

| 23 | Iris | Pietreni | 6 | 77.6 | 12.9 | 4.3 |

| 24 | Topa-Varciorog | Varciorog | 9.5 | 109 | 11.5 | 4.4 |

References

- Jokiel, P. Man and water. Acta Geogr. Lodz. 2024, 115, 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman, S.N.; Curran, A.; Bouwer, L.M. Floods have become less deadly: An analysis of global flood fatalities 1975–2022. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 6327–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R. Economic ‘normalisation’ of disaster losses 1998–2020: A literature review and assessment. Environ. Hazards 2020, 20, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekarova, P.; Bacova Mitkova, V.; Miklanek, P. Flash Flood on July 21, 2014 in the Vratna Valley. In New Developments in Environmental Science and Geoscience, Proceedings of the International Conference on Environmental Science and Geoscience (ESG 2015), Vienna, Austria, 15–17 March 2015; Mastorakis, N.E., Buluceva, A., Eds.; INASE: Vienna, Austria, 2015; pp. 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Borga, M.; Stoffel, M.; Marchi, L.; Marra, F.; Jakob, M. Hydrogeomorphic response to extreme rainfall in headwater systems: Flash floods and debris flows. J. Hydrol. 2014, 518, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surian, N.; Righini, M.; Lucìa, A.; Nardi, L.; Amponsah, W.; Benvenuti, M.; Borga, M.; Cavalli, M.; Comiti, F.; Marchi, L.; et al. Channel response to extreme floods: Insights on controlling factors from six mountain rivers in northern Apennines, Italy. Geomorphology 2016, 272, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, T.; Franczak, P.; Kroczak, R.; Cabaj, W.; Kołodziej, A. The impact of extreme rainfall and flash floods on the flood risk management process and geomorphological changes in small Carpathian catchments: A case study of the Kasiniczanka river (Outer Carpathians, Poland). Nat. Hazards 2017, 88, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucała-Hrabia, A.; Kijowska-Strugała, M.; Bryndal, T.; Cebulski, J.; Kiszka, K.; Kroczak, R. An integrated approach for investigating geomorphic changes due to flash flooding in two small stream channels (Western Polish Carpathians). J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2020, 31, 100731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaume, E.; Bain, V.; Bernardara, P.; Newinger, O.; Barbuc, M.; Bateman, A.; Blaškovićová, L.; Blöschl, G.; Borga, M.; Dumitrescu, A.; et al. A compilation of data on European flash floods. J. Hydrol. 2009, 367, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, L.; Borga, M.; Preciso, E.; Gaume, E. Characterization of selected extreme flash floods in Europe and implications for flood risk management. J. Hydrol. 2010, 394, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, T. Local flash floods in Central Europe: A case study of Poland. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.—Nor. J. Geogr. 2015, 69, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Coma, S.; Artigas, P.; Cuervo, P.F.; De Elías-Escribano, A.; Fantozzi, M.C.; Colangeli, G.; Córdoba, A.; Marquez-Guzman, D.J.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Borrás, C.; et al. Infectious disease risk after the October 2024 flash flood in Valencia, Spain: Disaster evolution, strategic scenario analysis, and extrapolative baseline for a One Health assessment. One Health 2025, 21, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, T. Hydrological parameters of rainstorm-inducted flash floods in the Polish, Slovakian and Romanian parts of the Carpathians. Przegląd Geogr. 2014, 86, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montz, B.E.; Grunfest, E. Flash flood mitigation: Recommendations for research and applications. Nat. Hazards 2002, 4, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kron, W. Flood risk, hazard, exposure, vulnerability. In Flood Defence; Wu, B., Wang, Z.Y., Wang, G.G.H., Huang, H., Huang, J., Eds.; Science Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 33–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kron, W. Changing flood risk—A re-insurance’s viewpoint. In Changes in Flood Risk in Europe; Kundzewicz, Z.W., Ed.; IAHS Special Publication 10; SCS Press: Wallingford, UK, 2012; pp. 459–477. [Google Scholar]

- Merz, B.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Delgado, J.; Hundecha, Y.; Kreibich, H. Detection and attribution of changes in flood hazard and risk. In Changes in Flood Risk in Europe; Kundzewicz, Z.W., Ed.; IAHS Special Publication 10; SCS Press: Wallingford, UK, 2012; pp. 435–458. [Google Scholar]

- McClymont, K.; Morrison, D.; Beevers, L.; Carmen, E. Flood resilience: A systematic review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1151–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczuk, T.; Dąbrowska, M. Commentary to Synoptic Situation of Poland. IMGW-PIB. 2014. Available online: http://pogodynka.pl/polska/komentarz (accessed on 19 July 2018).

- Gaume, E.; Borga, M. Post-flood field investigations in upland catchments after major flash floods: Proposal of a methodology and illustrations. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2008, 1, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumbroso, D.; Gaume, E. Reducing the uncertainty in indirect estimates of extreme flash flood discharges. J. Hydrol. 2012, 414–415, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, V.T. Open-Channel Hydraulics; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Biernat, B.; Bogdanowicz, E.; Czarnecka, H.; Dobrzyńska, I.; Fal, B.; Karwowski, S.; Skorupska, B.; Stachy, J. Zasady Obliczania Maksymalnych Rocznych Przepływów Rzek Polskich o Określonym Prawdopodobieństwie Pojawienia Się; IMGW: Warsaw, Poland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Françou, J.; Rodier, J.A. Essai de classification des crues maximales: Floods and their Computation. In Proceedings of the Leningrad Symposium, Leningrad, USSR, 15–22 August 1967; IAHS–UNESCO–WMO: Louvain, Belgium, 1969; pp. 518–527. [Google Scholar]

- Detailed geology map of Poland 1: 50 000—Sheet Łącko, PIG, Krakow. Available online: https://bazadata.pgi.gov.pl/data/smgp/arkusze_skany/smgp1034.jpg (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Parczewski, W. Warunki występowania nagłych wezbrań na małych ciekach. Wiadomości Służby Hydrol. I Meteorol. 1960, 8, 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- Verez, M.; Nemeth, I.; Schlaffer, R. The effects of flash floods on gully erosion and alluvial fan accumulation in the Kőszeg Mountains. In Geomorphological Impacts of Extreme Weather, Case Studies from Central and Eastern Europe; Lóczy, D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczuk, I.; Mykhnowych, A.; Pylypovych, O.; Rud’ko, G. Extreme exogenous processes in Ukrainian Carpathians. In Geomorphological Impacts of Extreme Weather: Case Studies from Central and Eastern Europe; Lóczy, D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroczak, R.; Bryndal, T.; Bucała, A.; Fidelus, J. The development, temporal evolution and environmental influence of an unpaved road network on mountain terrain: An example from the Carpathian Mts. (Poland). Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 75, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łajczak, A.; Margielewski, W.; Rączkowska, Z.; Święchowicz, J. Contemporary geomorphic processes in the Polish Carpathians under changing human impact. Episodes 2014, 37, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y. Landslides and debris flows caused by an extreme rainstorm on 21 July 2012 in mountains near Beijing, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, T.; Kroczak, R.; Kijowska-Strugała, M.; Bochenek, W. How human interference changes the drainage network operating during heavy rainfalls in a medium-high relief flysch mountain catchment? The case study of the Bystrzanka catchment (Outer Carpathians, Poland). Catena 2020, 194, 104662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, T. Flash floods: Theoretical and practical aspects of the identification of the flood hazard zone in small Carpathian catchments. Czas. Geogr. 2025, 96, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryndal, T.; Cabaj, W.; Suligowski, R. Hydrometeorologiczna interpretacja gwałtownych wezbrań małych cieków w źródłowej części Wielopolki w dniu 25 czerwca 2009 roku. In Monografie Komitetu Inżynierii Środowiska PAN, 69; Magnuszewski, A., Ed.; Komitet Inżynierii Środowiska Polskiej Akademii Nauk: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 81–91, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Bryndal, T.; Cabaj, W.; Gębica, P.; Kroczak, R.; Suligowski, R. Gwałtowne wezbrania spowodowane nawalnymi opadami deszczu w zlewni potoku Wątok (Pogórze Ciężkowickie). In Woda w Badaniach Geograficznych; Ciupa, T., Suligowski, R., Eds.; Uniwersytet Jana Kochanowskiego w Kielcach: Kielce, Poland, 2010; pp. 307–319, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Bryndal, T.; Cabaj, W.; Suligowski, R. Gwałtowne wezbrania potoków Kisielina i Niedźwiedź w czerwcu 2009 r. (Pogórze Wiśnickie). In Obszary Metropolitarne we Współczesnym Środowisku Geograficznym; Barwiński, M., Ed.; Wydział Nauk Geograficznych Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2010; pp. 337–348, (In Polish with English Summary). [Google Scholar]

- Sawaf, M.; Kawanisi, K. Assessment of mountain river streamflow patterns and flood events using information and complexity measures. J. Hydrol. 2020, 590, 125508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfatmiri, Y.; Bahreinimotlagh, M.; Jabbari, E.; Kawanisi, K.; Hasanabadi, A.; Sawaf, M. Application of Acoustic Tomographic Data to the Short-Term Streamflow Forecasting Using Data-Driven Methods and Discrete Wavelet Transform. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the assessment and management of flood risks. Off. J. Eur. Union 2007, L 288.27, 27–34. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2007/60/oj (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Flood Zones. The Official Webside of US Department of Homeland Security. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/about/glossary/flood-zones (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- World Bank Group. Data Cataloque. Available online: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search?fq=identification%2Fcollection_id%2Fany(col:col%20eq%20%27RDL%27)&q=&rows=50 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Ozga-Zielińska, M.; Kupczyk, E.; Ozga-Zieliński, B.; Suligowski, R.; Niedbała, J.; Brzeziński, J. Powodziogenność Rzek Pod Kątem Bezpieczeństwa Budowli Hydrotechnicznych i Zagrożenia Powodziowego; Materiały Badawcze IMGW, Seria: Hydrologia i Oceanologia, 29; IMGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Herschy, R.W. The World’s Maximum Observed Floods. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2002, 13, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokiel, P.; Tomalski, P. Odpływy maksymalne w rzekach Polski. Czas. Geogr. 2004, 75, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Castellarin, A. Probabilistic Envelope Curves for Design Flood Estimation at Ungauged Sites. Water Resour. Res. 2007, 43, W04406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimikou, M.A. Envelope Curves for Extreme Flood Events in North-Western and Western Greece. J. Hydrol. 1984, 67, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bryndal, T.; Buczek, K.; Franczak, P.; Górnik, M.; Kroczak, R.; Witkowski, K.; Faracik, R. Effects of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events on the Functioning of Mountain Environments in the Ochotnica Catchment (Outer Carpathians, Poland) and Recommendations for Adaptation Strategies. Water 2025, 17, 3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223244

Bryndal T, Buczek K, Franczak P, Górnik M, Kroczak R, Witkowski K, Faracik R. Effects of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events on the Functioning of Mountain Environments in the Ochotnica Catchment (Outer Carpathians, Poland) and Recommendations for Adaptation Strategies. Water. 2025; 17(22):3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223244

Chicago/Turabian StyleBryndal, Tomasz, Krzysztof Buczek, Paweł Franczak, Marek Górnik, Rafał Kroczak, Karol Witkowski, and Robert Faracik. 2025. "Effects of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events on the Functioning of Mountain Environments in the Ochotnica Catchment (Outer Carpathians, Poland) and Recommendations for Adaptation Strategies" Water 17, no. 22: 3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223244

APA StyleBryndal, T., Buczek, K., Franczak, P., Górnik, M., Kroczak, R., Witkowski, K., & Faracik, R. (2025). Effects of Severe Hydro-Meteorological Events on the Functioning of Mountain Environments in the Ochotnica Catchment (Outer Carpathians, Poland) and Recommendations for Adaptation Strategies. Water, 17(22), 3244. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223244